ABSTRACT

Although some bacteria, including Chromohalobacter salexigens DSM 3043, can use glycine betaine (GB) as a sole source of carbon and energy, little information is available about the genes and their encoded proteins involved in the initial step of the GB degradation pathway. In the present study, the results of conserved domain analysis, construction of in-frame deletion mutants, and an in vivo functional complementation assay suggested that the open reading frames Csal_1004 and Csal_1005, designated bmoA and bmoB, respectively, may act as the terminal oxygenase and the ferredoxin reductase genes in a novel Rieske-type oxygenase system to convert GB to dimethylglycine in C. salexigens DSM 3043. To further verify their function, BmoA and BmoB were heterologously overexpressed in Escherichia coli, and 13C nuclear magnetic resonance analysis revealed that dimethylglycine was accumulated in E. coli BL21(DE3) expressing BmoAB or BmoA. In addition, His-tagged BmoA and BmoB were individually purified to electrophoretic homogeneity and estimated to be a homotrimer and a monomer, respectively. In vitro biochemical analysis indicated that BmoB is an NADH-dependent flavin reductase with one noncovalently bound flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) as its prosthetic group. In the presence of BmoB, NADH, and flavin, BmoA could aerobically degrade GB to dimethylglycine with the concomitant production of formaldehyde. BmoA exhibited strict substrate specificity for GB, and its demethylation activity was stimulated by Fe2+. Phylogenetic analysis showed that BmoA belongs to group V of the Rieske nonheme iron oxygenase (RO) family, and all the members in this group were able to use quaternary ammonium compounds as substrates.

IMPORTANCE GB is widely distributed in nature. In addition to being accumulated intracellularly as a compatible solute to deal with osmotic stress, it can be utilized by many bacteria as a source of carbon and energy. However, very limited knowledge is presently available about the molecular and biochemical mechanisms for the initial step of the aerobic GB degradation pathway in bacteria. Here, we report the molecular and biochemical characterization of a novel two-component Rieske-type monooxygenase system, GB monooxygenase (BMO), which is responsible for oxidative demethylation of GB to dimethylglycine in C. salexigens DSM 3043. The results gained in this study extend our knowledge on the catalytic reaction of microbial GB degradation to dimethylglycine.

KEYWORDS: glycine betaine monooxygenase, Rieske-type oxygenase, N-demethylation, Chromohalobacter salexigens DSM 3043

INTRODUCTION

Glycine betaine (N,N,N-trimethylglycine [GB]) is widely available in the environment and accumulated by many microbes and plants in response to environmental stress, especially to salt stress. It also plays an important role in some mammals as a source of methyl group (1). Under osmotic stress conditions, most of the microorganisms accumulate GB by uptake from the environment via various transport systems in the betaine/choline/carnitine transporter (BCCT) family (2), major facilitator superfamily (MFS) (3), and/or the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters located on cellular membranes, or they produce it intracellularly via choline oxidation pathway, with betaine aldehyde as the intermediate (4, 5). Moreover, some halophilic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria, halophilic cyanobacteria, and halophilic methanogenic archaebacteria can use glycine in de novo synthesis of GB through the action of methyltransferases with S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) as a methyl donor (6, 7).

Besides acting as an organic osmolyte, GB can be used as a source of carbon, nitrogen, and energy in many bacteria. Under anaerobic conditions, GB is degraded by fermentation, reduction, or oxidation reactions to produce dimethylglycine, trimethylamine, acetate, or butyrate, etc. (8, 9). Under aerobic conditions, GB can also be catabolized by many microorganisms isolated from diverse habitats, including the members in the genera Agrobacterium, Pseudomonas, Micrococcus, Streptomyces (10), Arthrobacter (11), Corynebacterium (12), Sinorhizobium and other Rhizobiaceae (13), Chromohalobacter (14), and Halomonas (14). Moreover, Kortstee observed that all the choline-utilizing bacteria tested were capable of growth on media with GB, dimethylglycine, or sarcosine as the sole source of carbon and nitrogen, suggesting that these bacteria could aerobically decompose GB to glycine through a progressive demethylation reaction, with dimethylglycine and sarcosine as the metabolic intermediates (10). So far, two types of enzymes involved in the initial step of aerobic microbial GB catabolism have been reported. The first type is betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase (BHMT; EC 2.1.1.5), which catalyzes the transfer of a methyl group from GB to homocysteine, producing dimethylglycine and methionine. The enzyme activities were detected in the crude extracts of the species of Pseudomonas (15) and Sinorhizobium (16). In addition, Barra and colleagues identified the SMc04325 open reading frame (ORF) from Sinorhizobium meliloti strain 102F34 as the BHMT-encoding gene (17), and the native BHMT protein purified from Aphanothece halophytica was proven to be an octameric structure (18). The second type of enzyme responsible for the first step of aerobic GB catabolism was found in Pseudomonas aeruginosa (19) and Pseudomonas syringae (20). Through the strategies of transposon mutagenesis and gene disruption, the gbcA (PA5410) and gbcB (PA5411) genes were proven to be necessary for GB catabolism in P. aeruginosa (19), and their overexpression was shown to be sufficient to reduce intracellular GB pool (21). Bioinformatics analysis predicted that the gbcA and gbcB genes might encode a dioxygenase to remove a methyl group from GB, producing dimethylglycine and perhaps formaldehyde (19).

As a model organism for studying the mechanism of prokaryotic osmoregulation, the complete genome sequence of Chromohalobacter salexigens DSM 3043 had been determined by the Joint Genome Institute of the U.S. Department of Energy (22). The strain can not only use GB as the sole source of carbon and energy but also accumulate it intracellularly under high-salinity environments (14). Previous studies had shown that C. salexigens DSM 3043 also can grow on medium with dimethylglycine as the sole source of carbon and energy, and the disruption of sarcosine oxidase-encoding genes impairs its growth on mineral salt medium with GB as the sole carbon source (23), suggesting that GB could be aerobically catabolized to glycine by three successive demethylation reactions, with dimethylglycine and sarcosine as the intermediates. In this report, with a combination of genetic, bioinformatics, and biochemical approaches, we describe the characterization of the genetic and biochemical mechanisms for the initial step of the GB degradation pathway in the moderate halophile C. salexigens DSM 3043.

RESULTS

Identification of a two-gene cluster in C. salexigens DSM 3043.

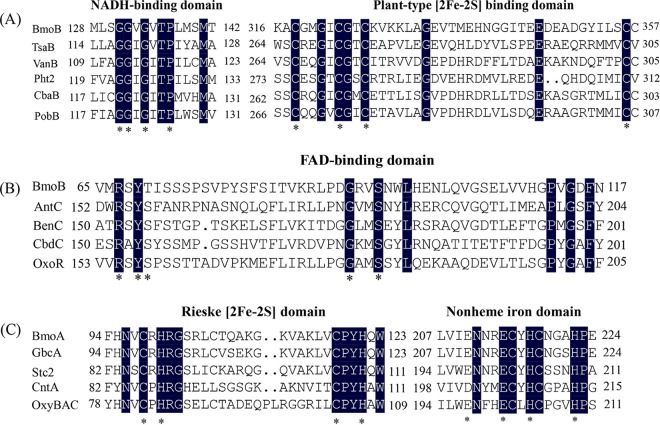

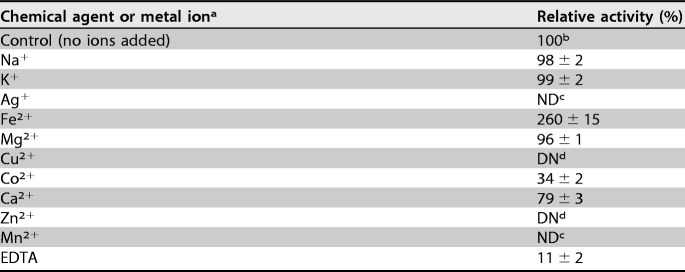

C. salexigens DSM 3043 can utilize GB as a sole source of carbon and nitrogen (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Therefore, a BLASTP analysis of C. salexigens DSM 3043 (GenBank accession number NC_007963.1) was performed to identify candidate genes involved in the first step of the GB catabolism pathway using the two-gene cluster identified as gbcAB (PA5410 and PA5411) from P. aeruginosa PAO1 as the query sequences (19). Csal_1004 and Csal_1005 exhibited good homology with PA5410 (66% identity/81% similarity) and PA5411 (76% identity/84% similarity), respectively. Csal_1005 is 1,107 bp in length and encodes a predicted 368-amino-acid protein. Conserved domain analysis revealed the presence of conserved sequences for the NAD(P)H-binding domain (GGXGXXP) (Fig. 1A), the plant-type [2Fe-2S] domain (CX4CX2CX29C) (Fig. 1A), and the flavin-binding domain (RXYSX19-20GX2S) (Fig. 1B) in the theoretical protein sequence of Csal_1005 (where X represents any amino acid residue). Directly upstream of Csal_1005, Csal_1004 encodes a predicted 428-amino-acid protein that shares amino acid sequence similarity with the catalytic α-subunits of some function-characterized Rieske nonheme iron oxygenases (ROs), such as the stachydrine demethylase (Stc2) (46% identity) from Sinorhizobium meliloti 1021 (24) and the oxygenase component of naphthalene 1,2-dioxygenase from Pseudomonas sp. strain NCIB 9816-4 (34%) (25). Conserved domain analysis revealed that Csal_1004 contains the conserved sequence CXHX15–17CX2H, which binds the Rieske-type [2Fe-2S] cluster at its N-terminal region (Fig. 1C), and one nonheme Fe(II) domain, (E/D)X2HX4H, at its C-terminal region (Fig. 1C). Therefore, the Csal_1004-encoded protein might be a Rieske-type oxygenase. Based on the results of protein conserved domain analysis, we hypothesized that Csal_1004 and Csal_1005 potentially function as the terminal oxygenase component and the ferredoxin reductase component of the Rieske-type oxygenase system which is involved in the degradation of GB to dimethylglycine, and designated the bmoA and bmoB genes, respectively.

FIG 1.

Conserved domain analysis of BmoA and BmoB from C. salexigens DSM 3043. (A) Identification of a NADH-binding domain and a plant-type [2Fe-2S] binding domain in the BmoB by amino acid sequence alignment with those of the flavin reductase components in the Rieske nonheme iron oxygenase (RO) class IA, as classified by Batie et al. (44). (B) Identification of a flavin-binding domain in the BmoB by amino acid sequence alignment with those of the flavin reductases in the RO class IB, as classified by Batie et al. (44). (C) Identification of a Rieske [2Fe-2S] domain and a nonheme Fe(II) domain in the BmoA by amino acid sequence alignment with those of the members in the RO family. Numbers represent the positions of the residues in the complete amino acid sequence of the following proteins (accession number): BmoB (499825574), a GB monooxygenase reductase component from C. salexigens DSM 3043; TsaB (AAC44805), a toluene sulfonate methyl-monooxygenase reductase component from Comamonas testosteroni T-2; VanB (O05617), a vanillate O-demethylase oxidoreductase from Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199; Pht2 (Q05182), a phthalate 4,5-dioxygenase reductase subunit from P. putida NMH102-2; CbaB (Q44257), a 3-chlorobenzoate-3,4-dioxygenase reductase subunit from Alcaligenes sp. strain BR60; PobB (Q52186), a phenoxybenzoate dioxygenase ferredoxin reductase from Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes POB310; AntC (AAC34815), an anthranilate dioxygenase reductase from Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1; BenC (BAB70700), a benzoate 1,2-dioxygenase reductase from Rhodococcus sp. strain RHA1; CbdC (CAA55683), a 2-halobenzoate 1,2-dioxygenase reductase from Pseudomonas cepacia 2CBS; OxoR (CAA73201), a 2-oxo-1,2-dihyroquinoline 8-monooxygenase reductase from P. putida 86; BmoA (759867680), the terminal oxygenase component of GB monooxygenase from C. salexigens DSM 3043; GbcA (15600603), the predicted component of GB dioxygenase from P. aeruginosa PAO1; Stc2 (AAK65058), a stachydrine demethylase from S. meliloti 1021; CntA (EEX03955), the terminal oxygenase component of carnitine oxygenase from A. baumannii ATCC 19606; and OxyBAC (WP_068587002), benzalkonium chloride oxygenase from Pseudomonas sp. BIOMIG1. The amino acid residues conserved in the domains are indicated by asterisks (*), while identical amino acids residues in the aligned sequences are shown in black.

Targeted gene deletion and complementation assays.

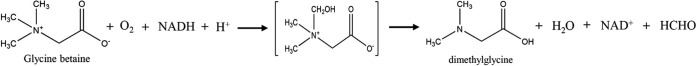

To verify the role of the bmoA and bmoB genes involved in the first step of GB degradation, the unmarked in-frame deletion mutants of bmoA (3043ΔbmoA mutant strain) and bmoB (3043ΔbmoB mutant strain) were constructed using the allelic exchange method. The wild-type bmoA gene was reduced to an open reading frame (ORF) of 39 nucleotides encoding only 12 amino acids (MDLLPSLHIVQG), while the wild-type bmoB gene was reduced to an ORF of 45 nucleotides encoding 14 amino acids (MTQNFFKSHVAIEF). C. salexigens DSM 3043, ZW4-1, 3043ΔbmoA, and 3043ΔbmoB were inoculated onto C-M63 agar plates supplemented with glucose, GB, or dimethylglycine at a final concentration of 20 mM as the sole carbon source to determine their GB- and dimethylglycine-degrading abilities. As predicted, strains 3043ΔbmoA and 3043ΔbmoB could utilize glucose or dimethylglycine as the sole carbon source but were incapable of growth on 20 mM GB as the sole source of carbon, while C. salexigens DSM 3043and ZW4-1 could utilize glucose, GB, or dimethylglycine as the sole source of carbon (Fig. S2), indicating that the bmoA and bmoB genes are essential for the conversion of GB to dimethylglycine in C. salexigens DSM 3043.

To further determine whether the deficiency in GB-to-DMG conversion was due to inactivation of bmoA and bmoB, the C. salexigens 3043ΔbmoA and 3043ΔbmoB strains were complemented by their wild-type genes which were expressed under the control of their native promoters with a broad-host-range vector, pBBR1MCS. After the plasmids for complementation were conjugated into the mutant strains, strain 3043ΔbmoA carrying pBBR1MCS-bmoA and strain 3043ΔbmoB carrying pBBR1MCS-bmoB partially restored their abilities to use GB as the sole source of carbon in C-M63 medium (Fig. 2), while as the negative control, strains 3043ΔbmoA and 3043ΔbmoB carrying pBBR1MCS did not grow on the same medium (data not shown), confirming the role of these two genes in GB degradation to dimethylglycine. In addition, these results also implied that the bmoA and bmoB genes may utilize a common intergenic DNA sequence (286 bp) as their promoter regions in C. salexigens cells, although the two genes are predicted to be transcribed in opposite directions (Fig. S3). Interestingly, the 286-bp intergenic region (containing the bmoB promoter region) exhibited 41.35% sequence similarity with its reverse complement sequence (containing the bmoA promoter region) (Fig. S4). Compared manually with the known promoter sequences of E. coli or C. salexigens ectA (26), no conserved promoter sequence was detected. However, using the promoter prediction software NNPP version 2.2 (http://www.fruitfly.org/seq_tools/promoter.html) (27), a possible promoter region of Csal_1005 was detected, and its predicted transcription start site was located 45 bp upstream of the translation start codon (Fig. S4). To verify the actual promoter regions of Csal_1004 and Csal_1005, S1 nuclease mapping and primer extension experiments should be performed in future studies.

FIG 2.

Growth of C. salexigens ZW4-1 (filled circle), 3043ΔbmoA(pBBR1MCS-bmoA) (open triangle), and 3043ΔbmoB(pBBR1MCS-bmoB) (open square) at 37°C in C-M63 liquid medium supplemented with glucose (A), GB (B), or dimethylglycine (C) as the sole source of carbon.

Functional characterization of BmoA and BmoB in E. coli cells.

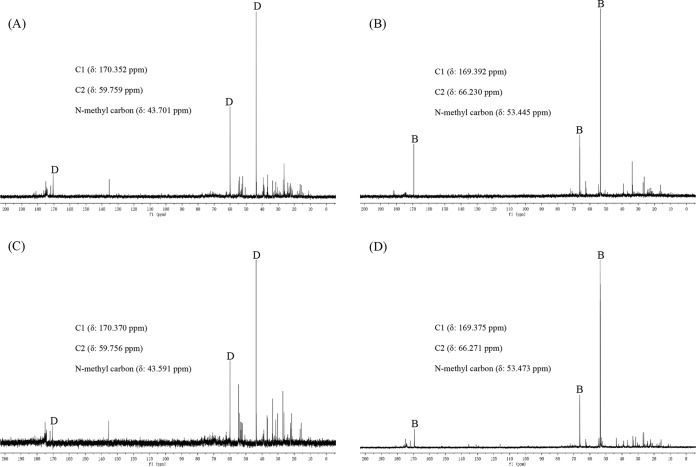

To check the proposed function of BmoA and BmoB, plasmid pACYC-bmoA-bmoB, which contained the bmoA and bmoB genes under the control of their respective T7 promoters in vector pACYCDuet-1, was transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3), while plasmids pACYC-bmoA, pACYC-bmoB, and pACYCDuet-1 were individually transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) as the control. The transformed cells were grown in LB liquid medium, and protein expression was induced by isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG). Since yeast extract in LB medium is known to contain 1 to 3% (wt/wt) GB (28), the GB transporters located on the cellular membrane of E. coli could transport them from growth media into the cells (29). As long as both bmoA and bmoB expression products are biologically active and sufficient for bioconversion of GB to dimethylglycine, dimethylglycine will be detected intracellularly in E. coli cells. As shown in Fig. 3, 13C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analysis revealed that dimethylglycine was indeed accumulated in E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pACYC-bmoA-bmoB, whereas GB was accumulated in E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pACYC-bmoB or pACYCDuet-1. Unexpectedly, dimethylglycine was also found to accumulate in E. coli BL21(DE3) carrying plasmid pACYC-bmoA, which suggested that the cellular components in E. coli cells could substitute the function of the bmoB-encoded protein and convert GB to dimethylglycine in the presence of BmoA. This phenomenon has been observed in many multicomponent oxygenase systems (30), in which the flavin reductase components are usually nonspecific and interchangeable and can be substituted by the flavin reductases from other bacteria, such as SsuE, the flavin reductase component of alkanesulfonate monooxygenase from E. coli (31). The possibility that the SsuE or other uncharacterized ferredoxin reductases in E. coli replace the function of BmoB may well explain why E. coli BL1(DE3) carrying the bmoA gene in the absence of the bmoB gene was still capable of degrading GB to dimethylglycine. In addition, to test whether the promoter regions of bmoA and bmoB could be recognized by E. coli transcriptional system, plasmid pBBR1MCS-bmoA-bmoB, which contained the full-length bmoA and bmoB genes, and their intergenic sequence was introduced into competent E. coli BL21(DE3) or E. coli DH5α cells. 13C NMR analysis indicated that GB, but not dimethylglycine, was accumulated in E. coli (data not shown). The failure of E. coli BL21(DE3) or DH5α carrying pBBR1MCS-bmoA-bmoB to decompose GB to dimethylglycine may due to many possible reasons, including a lack of recognition of C. salexigens promoter regions by E. coli RNA polymerases or a lack of the necessary transcriptional regulatory factor to activate gene transcription in E. coli.

FIG 3.

Natural-abundance 13C NMR spectra of ethanolic extracts from E. coli BL21(DE3) cells harboring different recombinant plasmids grown in LB medium after induction with IPTG. Details for the induction of protein with IPTG and sample preparation are given in Materials and Methods. (A) E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pACYC-bmoA. (B) E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pACYC-bmoB. (C) E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pACYC-bmoA-bmoB. (D) E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pACYCDuet-1. B, glycine betaine; D, dimethylglycine.

Purification of His6-tagged BmoA and BmoB.

To characterize the biochemical properties of BmoA and BmoB, we individually overexpressed them using the pET28a(+) expression system in E. coli BL21(DE3) as C-terminal and N-terminal His6-tagged fusion proteins to facilitate protein purification. We found that the fusion protein with a His6 tag at the N terminus of BmoA (His6-BmoA) was expressed as inclusion bodies and did not show activity, although many attempts, including reducing the incubation temperature and the concentration of inducer, or replacing the expression host and vector to enhance the yield as the soluble form, were made. Fortunately, this situation had been greatly improved when the His6 tag was switched from the N terminus to the C terminus of the BmoA (BmoA-His6) (Fig. S5A), and the BmoA-His6 was predominantly expressed as the soluble form in E. coli. On the other hand, the recombinant protein with a His6 tag added at the N terminus of the BmoB (His6-BmoB) (Fig. S5A) was found in the supernatant and sediment of E. coli cell lysate. As estimated from SDS-PAGE, BmoA-His6 and His6-BmoB represented roughly 20 to 40% of the total protein in the cell extracts. After being individually purified to electrophoretic homogeneity using a nickel dication-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni2+-NTA)-chelating column, the yields of purified BmoA-His6 and His6-BmoB were estimated to be about 22.6 ± 3.5 mg and 13.8 ± 2.5 mg per liter of culture. The enzyme preparations of His6-BmoB were stable for at least 2 weeks when stored at −40°C in elution buffer with no addition of enzyme stabilizer, whereas the BmoA-His6 solution was very unstable and only maintained no more than 10% residual activity after the same treatment. Although we tried to add the protective agents, such as glycerol, to the BmoA enzyme preparation, the protective effect was still very limited.

Molecular weights and subunit composition.

SDS-PAGE analysis revealed the presence of only one protein band for purified BmoA-His6 or His6-BmoB, and their molecular masses were determined to be approximately 52.5 kDa and 47.7 kDa, respectively, in agreement with the predicted size of the proteins. The native molecular masses of purified BmoA-His6 and His6-BmoB were estimated by gel filtration to be 154.8 and 45.1 kDa, respectively (Fig. S5B), suggesting a homotrimeric structure (α3) for BmoA and a monomeric structure for BmoB.

Biochemical characterization of BmoB as an NAD(P)H-dependent flavin reductase. (i) Spectroscopic properties.

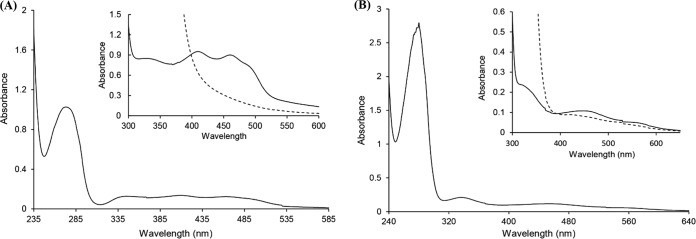

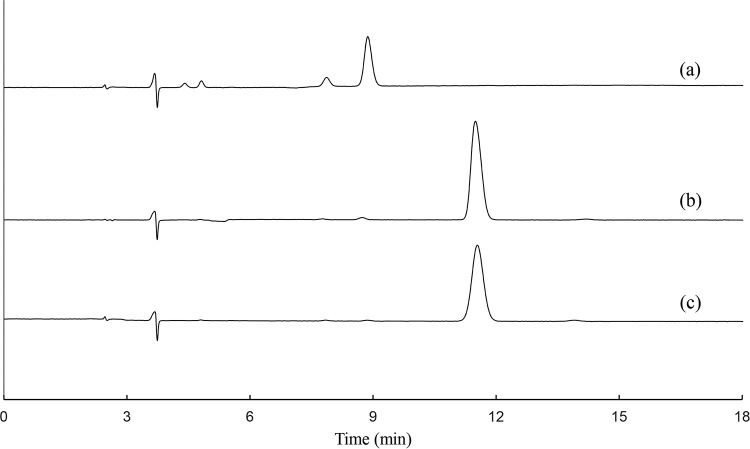

The purified His6-BmoB preparation was bright yellow in color. The UV-visible spectra of the enzyme showed absorption maxima at 275, 325, 410, and 460 nm, with a shoulder at about 492 nm (Fig. 4A), which are typical of a flavoprotein (32). After the addition of sodium dithionite, the absorption peaks in the visible range disappeared, indicating the reduction of enzyme-bound flavin. The flavin prosthetic group is readily dissociated from BmoB by treatment with 5% trichloroacetic acid, suggesting it is uncovalently bound. After the flavin was extracted by boiling, high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis identified it as FAD (Fig. 5). The molar ratio of FAD to protein was determined to be 0.66 ± 0.08, indicating that each BmoB contains one FAD molecule. It is likely that BmoB has lost part of its flavin during the purification process. Based on a molecular mass of 43.26 kDa, the contents of iron and acid-labile sulfide in the purified enzyme were determined to be 1.88 ± 0.05 mol and 1.76 ± 0.10 mol per mol His6-BmoB, respectively, in agreement with the presence of a properly assembled [2Fe-2S] center in His6-BmoB. These observations suggest that the native His6-BmoB contains one [2Fe-2S] center and one FAD per enzyme.

FIG 4.

UV-visible absorption spectra of the purified His6-BmoB (19.09 μM) (A) and BmoA-His6 (22.84 μM) (B) in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0). (A) The inset shows the magnified absorption spectra of the purified His6-BmoB (0.14 mM protein) before (solid line) and after (dashed line) the addition of sodium dithionite (2 mM). (B) The inset shows the magnified absorption spectra of BmoA-His6 before (solid line) and after (dashed line) the addition of sodium dithionite (2 mM).

FIG 5.

HPLC elution profiles identifying FAD as the flavin cofactor of His6-BmoB. (a) Authentic FMN. (b) Sample of flavin cofactor extracted from BmoB by heat treatment. (c) Authentic FAD.

(ii) Catalytic properties.

The flavin reductase activity of BmoB could only be measured after the enzyme had been purified, since it is impossible to measure the crude enzyme activity due to the existence of high background NADH oxidation activity even with that of the negative-control E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pET28a. BmoB could not only utilize NADH to reduce flavin mononucleotide (FMN), FAD, or riboflavin but also oxidize NADPH as the substrate, concomitantly producing hydrogen peroxide. The kinetic parameters of His6-BmoB were determined (Table 1), and NADH appeared to be the preferred electron donor over NADPH, while FMN was the most favored electron acceptor for BmoB compared with FAD and riboflavin. Interestingly, although FAD was found to be the native cofactor for BmoB, the oxidation rate for NADH in the presence of FMN was slightly higher than that in the presence of FAD. The addition of GB to the reaction mixtures did not result in any changes toward His6-BmoB activity on its substrates, and no formaldehyde or dimethylglycine was detected without BmoA-His6. The optimal pH was determined to be 7.5 in Tris-HCl buffer, with 47, 82, 85, and 62% of the activity maintained at pH 6.5, 7.0, 8.0, and 8.5, respectively. From the results obtained, it can be concluded that BmoB is an NAD(P)H-dependent flavin reductase.

TABLE 1.

Apparent kinetic parameters for the reductase activity of His6-BmoBa

| Substrate (concn range [μM] | Vmax (μmol · mg−1 · min−1) | Km (μM) | kcat (s−1) | Cosubstrate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NADH (12.5–200)b | 1.25 ± 0.07 | 43.94 ± 1.4 | 0.90 ± 0.01 | FAD |

| NADPH (12.5–800)b | 0.49 ± 0.05 | 257.80 ± 2.6 | 0.35 ± 0.01 | FAD |

| FAD (2.5–200)c | 5.90 ± 0.18 | 6.03 ± 0.13 | 4.25 ± 0.01 | NADH |

| FMN (2.5–200)c | 6.79 ± 0.12 | 17.31 ± 0.11 | 4.89 ± 0.01 | NADH |

| Riboflavin (2.5–500)c | 2.32 ± 0.15 | 111.83 ± 6.75 | 1.67 ± 0.01 | NADH |

Experiments were performed in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0) at 25°C. Values are means of and standard deviations of the results from three independent sets of experiments.

Determined with a fixed FAD concentration of 150 μM.

Determined with a fixed NADH concentration of 200 μM.

Biochemical characterization of BmoA as a Rieske-type oxygenase. (i) Spectroscopic properties.

The purified BmoA-His6 preparation was red-brown in color, and the air-oxidized enzyme had absorption maxima at 279, 326, and 460 nm, with a shoulder at about 572 nm (Fig. 4B), a typical characteristic and similar to the proteins containing a Rieske-type [2Fe-2S] center (33, 34). In fact, the entire absorbance spectrum of BmoA was almost the same as those of the choline monooxygenase (CMO) from Spinacia oleracea (35) and the terminal oxygenase (OxoO) of 2-oxo-1,2-dihydroquinoline 8-monooxygenase from P. putida 86 (32), which contain both a [2Fe-2S] cluster and mononuclear nonheme iron in a 1:1 ratio. After the addition of 2 mM sodium dithionite, the absorption peak at 460 nm decreased by about 29%, while two new absorption peaks appeared at 418 nm and 521 nm (Fig. 4B, inset). When the concentration of sodium dithionite was increased to 8 mM, the color of enzyme solution faded, and the absorption in the visible region disappeared, a phenomenon commonly observed in iron-sulfur proteins (35). The iron and acid-labile sulfide contents of BmoA-His6 were estimated to be 2.59 ± 0.12 and 1.93 ± 0.08 mol per mol enzyme monomer. After the addition of FeSO4 (1 mM) to the purified BmoA-His6, the enzyme solution was desalted with Sephadex G25 (Sigma). The iron content of purified BmoA-His6 increased to 3.09 ± 0.06 mol per mol enzyme monomer, indicating the corresponding subunit of iron-sulfur proteins contains one [2Fe-2S] cluster and one nonheme iron. Based on these data, it could be expected that the native BmoA-His6, as a homotrimer, contains a [2Fe-2S] center and mononuclear iron per subunit.

(ii) Catalytic properties.

The BMO activity of BmoA was measured by monitoring GB-dependent formaldehyde production in the presence of BmoB. Dimethylglycine and formaldehyde were absent if heat-denatured BmoA was used or if GB was omitted from the enzyme assay, which indicated that dimethylglycine and formaldehyde were derived enzymatically from GB. In the absence of BmoB, BmoA showed no detectable BMO activity. The observation that BmoA activity was absolutely dependent on the presence of BmoB supports our hypothesis that both components are required and sufficient for the conversion of GB to dimethylglycine. Although BmoB could use NADH or NADPH as the electron donors with different efficiencies, the activity of BmoA was strictly dependent on NADH, and GB degradation was negligible when NADPH was used instead of NADH, revealing the NADH-dependent GB monooxygenase activity. Maximal activity was obtained when the reaction mixtures were vigorously stirred on a magnetic stirrer. Under anaerobic conditions, no formaldehyde or dimethylglycine could be detected. However, after the anaerobic reaction mixtures were exposed to air, formaldehyde and dimethylglycine were detected in the reaction mixtures, indicating that the GB demethylation reaction was absolutely dependent on the presence of oxygen. The optimal pH and temperature for the enzyme were 7.5 and 30°C, respectively. With 5 mM NADH and 5 μM FAD as the cofactor, the apparent Km and kcat values of BmoA for GB were determined to be 1.20 ± 0.01 mM and 0.65 ± 0.10S−1, respectively. BmoA could use all three kinds of flavins as cofactors, and the specific activities of BmoA with FAD, FMN, and riboflavin as the cofactor were determined to be 11.64, 13.89, and 6.56 U/mg, respectively. The stoichiometry data showed that GB consumption was accompanied by the formation of equimolar amounts of dimethylglycine and formaldehyde under aerobic conditions.

(iii) Substrate specificity.

The substrate range of BmoA was investigated in vitro by measuring the formation of formaldehyde spectrophotometrically (Fig. S6) and detecting the potential substrate demethylation products with 13C NMR spectroscopy (Fig. S7). The results indicated that BmoA could specifically utilize GB as substrate, and did not show any activity on choline, l-carnitine, stachydrine, dimethylglycine, or sarcosine.

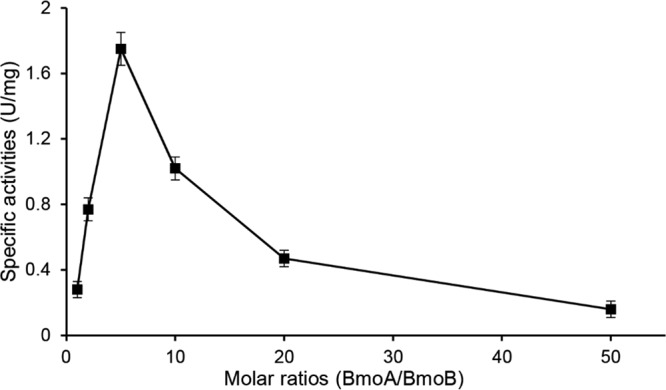

Effects of the molar ratios of BmoA to BmoB on BMO activity.

Since the BMO activity of BmoA was dependent on the presence of BmoB, the influence of molar ratio of BmoA to BmoB on BMO activity was investigated. As shown in Fig. 6, maximal specific activity was obtained when the ratio of BmoA to BmoB was 5:1, with FAD as the cofactor in vitro assays, indicating that the demethylation activity of BmoA was highly dependent on the molar ratio of BmoA to BmoB. Thus, the ratio of 5:1 was employed throughout the in vitro BMO activity assays.

FIG 6.

Effects of the molar ratios of BmoA to BmoB on BMO activity. The specific activities were measured by the amount of formaldehyde produced after shaking at 30°C for 30 min while keeping the concentration of BmoB constant at 1.5 μM and varying the concentration of BmoA (1.5 to 75 μM) in the reaction mixture containing 10 μM FAD, 5 mM NADH, and 2 mM GB.

Effects of flavin concentrations on BMO activity.

During the process of optimizing the concentrations of each component in the reaction mixture, we found that higher concentrations of flavins (>15 μM for FAD and >25 μM for FMN) would lead to a decrease in BmoA-specific activity but have no inhibitory effect on the flavin reductase activity of BmoB (data not shown). Inhibition by high flavin concentrations was also observed in the p-hydroxyphenylacetate hydroxylase from Acinetobacter baumannii (36) and the luciferase from Vibrio harveyi (37). It was believed that the excess oxidized flavin competed with the reduced flavin for the flavin-binding sites on the reductase, leading to the decline in electron transfer efficiency (36).

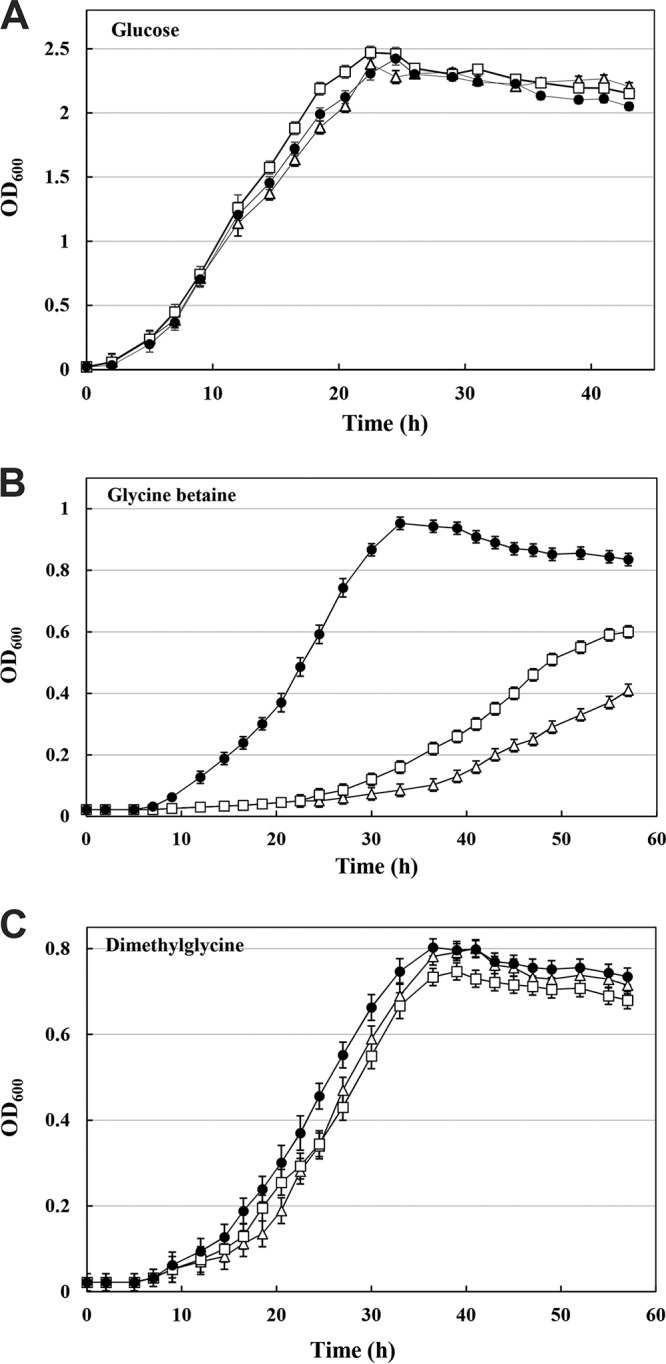

Effects of metal ions and EDTA on BMO activity.

As shown in Table 2, the BMO activity was significantly enhanced by Fe2+ and severely inhibited by heavy-metal ions, including Co2+, Mn2+, Zn2+, Cu2+, and Ag+. The presence of K+, Na+, or Mg2+ has no obvious influence on it activity, while the addition of Ca2+ resulted in 21% inhibition of activity. It should be noted that addition of the metal chelating-agent EDTA severely inhibited BMO activity, suggesting that the enzyme needs metal ions for its activity.

TABLE 2.

Effects of metal ions and EDTA on BMO activity

The final concentration of tested ions was 2 mM.

The activity of 4.29 U/mg was set as 100%.

ND, not detectable.

DN, the enzyme was denatured after the addition of ions.

DISCUSSION

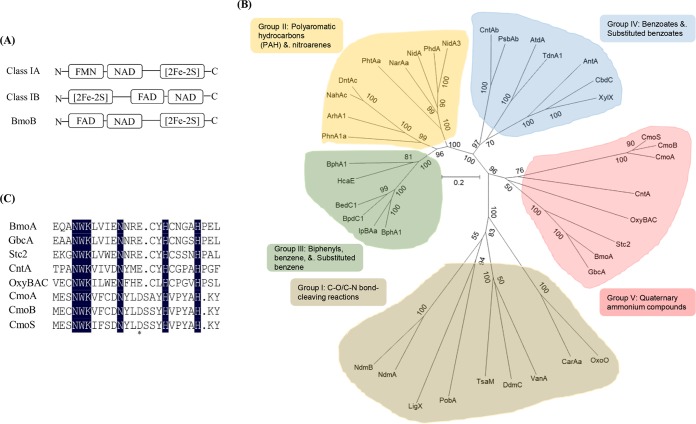

In this study, a novel RO system, GB monooxygenase (BMO), was identified and molecularly characterized. This system is composed of a Rieske-type oxygenase component (BmoA) and a NADH-dependent flavin reductase component (BmoB), and it catalyzes the oxidative N-demethylation of GB to dimethylglycine in C. salexigens DSM 3043. In terms of GB degradation products, the oxidation mechanism of BMO toward GB, similar to those of 4-methoxybenzoate monooxygenase (38) and dicamba monooxygenases (39), was proposed (Fig. 7). BMO catalyzes oxygen attack at a methyl group in GB, rather than the oxygenation of the aromatic ring that was observed in most other Rieske nonheme iron ring-hydroxylating oxygenases (RHOs), and it inserts an oxygen atom into the methyl C—H bond. The N-methyl group in GB is then oxidized to an N-methylol intermediate, and the intermediate would likely decompose spontaneously, releasing dimethylglycine and formaldehyde. Another possibility, that the activated oxygen species attacks the methyl group in a nucleophilic substitution-type reaction, can be excluded, since the reaction product would be methanol rather than formaldehyde in that case. Because the in vivo experiment indicated that dimethylglycine was accumulated in E. coli expressing BmoAB or BmoA, it can be confirmed that the predicted catabolism does occur in bacterial cytosol. On the other hand, formaldehyde, the second product of catalysis, is toxic to cells. It can either be assimilated into cell biomass via the various formaldehyde assimilation pathways or dissimilated via formate to carbon dioxide by the action of formaldehyde dehydrogenases and formate dehydrogenases, generating the reducing equivalents for energy generation and biosynthesis. BLAST searches of the C. salexigens DSM 3043 genome revealed in the vicinity of bmoA and bmoB genes and other locations in the genome, several putative ORFs may encode predicted glutathione-independent formaldehyde dehydrogenases (Csal_0335 and Csal_0995) and formate dehydrogenases (Csal_0997, Csal_1915, and Csal_1917).

FIG 7.

Proposed reaction mechanism for BMO-catalyzed conversion of GB to dimethylglycine in C. salexigens DSM 3043. A hypothetical intermediate (brackets) spontaneously decomposes in formaldehyde and dimethylglycine.

It is well known that prokaryotic RO systems are made up of two or three components. Most of these component-encoding genes are usually located on different loci that separated them for at least several kilobases (40, 41), while other genes are organized in one operon and transcribed in the same direction. However, this is not the case for the BMO-encoding genes (bmoA and bmoB) from C. salexigens DSM 3043. Although the two genes are found adjacent to each other, they are transcribed in divergent directions, which is an interesting gene arrangement that has rarely occurred in the function characterized RO systems. We believed that this arrangement increases the flexibility of the cells to cope with environmental changes, since the transcription of bmoB might be controlled not only by the intracellular concentration of GB but also by other environmental factors.

Among the biochemical characterized ROs, BmoA showed the highest sequence homology (46% similarity) to the stachydrine demethylase Stc2 from S. meliloti 1021 (42), while BmoB exhibited the highest sequence homology (27% similarity) to the reductase component of the benzoate dioxygenase from Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1 (43). The low amino acid sequence similarities suggest that BMO is a novel two-component Rieske-type monooxygenase system.

According to the classification system made by Batie et al. (44), multicomponent RHOs were classified into three main classes (classes I, II, and III) in terms of the number of protein components and the nature of their redox centers involved in electron transport from NAD(P)H to the oxygenase component. Class I RHOs, as the two-component oxygenase system, were further subdivided into subclass A and subclass B based on the cofactor (FMN/FAD) binding to the reductase component. Since biochemical characterization of BmoB showed the presence of FAD as the native cofactor, and an in vitro assay proved that BMO contains two components (BmoA and BmoB), BMO should belong to the class IB Rieske-type oxygenase. However, the FAD binding motif is found at the N terminus of BmoB and does not locate between the [2Fe-2S] binding domain and the NAD binding domain, suggesting that BMO does not belong to any of these classes (Fig. 8A). Carnitine oxygenase, a recently identified RO from A. baumannii ATCC 19606, has a similar modular arrangement (45).

FIG 8.

Identification of the putative Rieske-type protein involved in GB-to-dimethylglycine degradation from C. salexigens DSM 3043. (A) Organization of the cofactor binding domains in class IA, class IB, and BmoB. (B) Classification of the large subunits of 39 terminal oxygenase components in Rieske nonheme iron oxygenases. The phylogenetic tree, inferred by the neighbor-joining method, shows the relative positions of BmoA among other characterized ROs based on the Nam classification system (42). Bootstrap values for 1,000 replications are given. The scale bar represents two substitutions per 10 amino acids. The protein abbreviations, their corresponding species, and gi/accession numbers in the GenBank database are as follows: OxoO, P. putida 86, 2072732; CarAa, Pseudomonas sp. strain CA10, 2317678; VanA, Pseudomonas sp. HR199, 1946284; DdmC, Pseudomonas maltophilia DI-6, 55584974; TsaM, Comamonas testosteroni T-2, 1790867; PobA, P. pseudoalcaligenes POB310, 473250; LigX, Sphingomonas paucimobilis SYK-6, 4062861; NdmA, P. putida CBB5, AFD03116; NdmB, P. putida CBB5, AFD03117; BphA1, P. pseudoalcaligenes KF707, 151091; IpBAa, P. putida RE204, 2822265; BpdC1, Rhodococcus sp. strain M5, 927232; BedC1, P. putida ML2, 1168640; HcaE, E. coli K-12, 81170783; BphA1, Rhodococcus erythropolis TA421, 3059209; PhnA1a, Sphingomonas sp. strain CHY-1, 75455648; ArhA1, Sphingomonas sp. strain A4, 50725019; NahAc, Pseudomonas sp. strain JS42, 1224114; DntAc, Burkholderia cepacia R34, 17942397; PhtAa, Mycobacterium vanbaalenii PYR-1, 49072886; NarAa, Rhodococcus sp. strain NCIMB12038, 4704462; NidA, M. vanbaalenii PYR-1, 11038552; PhdA, Nocardioides sp. strain KP7, 7619816; NidA3, M. vanbaalenii PYR-1, 68053509; CntAb, P. putida F1, 1263180; PsbAb, Rhodopseudomonas palustris, 5360700; AtdA, Acinetobacter sp. strain YAA, 1395141; TdnA1, P. putida UCC22, 1841362; AntA, Acinetobacter sp. ADP1, 3511232; CbdC, Burkholderia cepacia 2CBS, 758210; XylX, P. putida TOL, 139861; CmoS, Spinacia oleracea, AAB52509; CmoB, Beta vulgaris, AAB80954; CmoA, Amaranthus tricolor, AAK82768; CntA, A. baumannii ATCC 19606, EEX03955; OxyBAC, Pseudomonas sp. BIOMIG1, 1057213843; Stc2, S. meliloti 1021, 16262853; BmoA, C. salexigens DSM 3043, 759867680; and GbcA, P. aeruginosa PAO1, 15600603. (C) Multiple-sequence alignment of BmoA and the members in group V of the RO family. The asterisk (*) indicates the conserved glutamate residue in the mononuclear iron center domain of microbial RO oxygenase component, while identical amino acids residues in the eight sequences are shown in black.

Although most of microbial ROs reported normally catalyze the initial oxygenation reaction of various aromatic compounds, more recently discovered ROs have been found to be capable of catalyzing non-ring-hydroxylating reactions (24, 45, 46). Studies on protein crystal structure revealed that the large subunit (α-subunit) of terminal oxygenase component in the oxygenase system is responsible for determining the substrate specificity of the enzyme (47). Although the terminal oxygenase components in RO systems share a conserved domain structure, their sequences are highly divergent (48). To gain insight into the evolutionary relationship between the BmoA and other characterized ROs, phylogenetic analysis of BmoA was conducted with the large subunits of 38 representative ROs. All of these ROs are divided into five groups (Fig. 8B), and BmoA is clustered into RO group V, a novel group established by Ertekin et al. (46), according to the nomenclature system of Nam et al. (49), who proposed another classification scheme based on the homology of the amino acid sequences of the large subunits of the terminal oxygenase components, and classified them into 4 groups (groups I to IV) according to substrate preferences. The members in the RO group V include the CntA of carnitine oxygenase from A. baumannii ATCC 19606 (45), the Stc2 (stachydrine demethylase) from S. meliloti 1021 (42), the GbcA as the predicted GB dioxygenase from P. aeruginosa PAO1 (19), the OxyBAC (benzalkonium chloride oxygenase) from Pseudomonas sp. strain BIOMIG1 (46), and three choline monooxygenases from plants (Fig. 8B). A common feature of these enzymes is that they could use quaternary ammonium compounds (QACs) as substrates and initiate the first step of QAC degradation through N-dealkylation reactions, attacking the C-N+ bond between the methyl group and quaternary N in QACs to remove the methyl group from the N atom.

Further analysis of the catalytic mononuclear iron centers in this newly established group revealed that all the terminal components of microbial ROs have the conserved glutamate residue instead of the conserved aspartate residue found in the other groups of ROs (Fig. 8C). The conserved glutamate is considered to be essential in intermolecular electron transfer from the Rieske center of one monomer to the active nonheme mononuclear iron site in the neighboring monomer (45, 50). The substitution of the original aspartate residue with glutamate in naphthalene dioxygenase (51) or glutamate with an aspartate residue in carnitine oxygenase resulted in a severe loss of enzyme activity (45). Interestingly, the same sites in the choline monooxygenases from plants in the RO group V were the conserved aspartate residue (Fig. 8C), the same as those ROs in the other groups. The roles of this residue in BmoA and other eukaryotic choline monooxygenases remain to be investigated in prospective work.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

GB, dimethylglycine, sarcosine, flavin mononucleotide (FMN), flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD), riboflavin, NADH, and NADPH were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chem (Shanghai, China). Nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) Sefinose resin, choline, carnitine, hydrogen peroxide, and isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG) were purchased from Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China). Stachydrine was purchased from Aladdin Bio-Chem Tech (Shanghai, China). Restriction enzymes, T4 DNA ligase, and Taq DNA polymerase were purchased from TaKaRa Biotech (Dalian, China) and used according to the manufacturer's procedures. All other chemical reagents used in this study were of analytical grade and are commercially available.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 3, and the primers are shown in Table 4. C. salexigens DSM 3043 and its mutants were routinely grown at 37°C in D5 medium (per liter, 50 g NaCl, 5 g MgSO4·7H2O, 5 g tryptone, and 3 g yeast extract [pH 7.5]) or in C-M63 medium [per liter, 50 g NaCl, 2 g (NH4)2SO4, 13.6 g KH2PO4, 3.6 g d-glucose, 0.12 g MgSO4, and 0.5 mg FeSO4·7H2O (pH 7.5)]. E. coli strains were aerobically cultivated in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (52) with shaking at 37°C and 180 rpm. For culture cells carrying an antibiotic resistance marker, antibiotics were added at the following concentrations: 50 μg · ml−1 rifampin (Rif), 70 μg · ml−1 chloramphenicol (Cm), and 50 μg · ml−1 kanamycin (Km). The concentrations of GB, dimethylglycine, or glucose were 20 mM when used as the sole carbon source in the defined media. Cell growth was monitored by measuring the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) with a UV2301II UV-visible spectrophotometer (Techcomp, Shanghai, China).

TABLE 3.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or descriptiona | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| Chromohalobacter salexigens | ||

| DSM 3043 | Wild type | DSMZb |

| ZW4-1 | Spontaneous rifampin-resistant mutant of C. salexigens DSM 3043 | 23 |

| 3043ΔbmoA | bmoA in-frame deletion mutant of strain ZW4-1, Rifr | This study |

| 3043ΔbmoB | bdmB in-frame deletion mutant of strain ZW4-1, Rifr | This study |

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | supE44 ΔlacU169 (Φ801acZΔM15) hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1 | TaKaRa |

| S17-1 | pro hsdR recA [(RP4-2 (Tc::Mu)(Km::Tn7))] | 23 |

| BL21(DE3) | F− ompT hsdSB(rB− mB−) gal dcm (DE3); T7 RNA polymerase gene under the control of the lacUV promoter | TianGen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pK18mobsacB | mob sacB (RP4) lacZ, Kmr | 54 |

| pK18mobsacB::ΔbmoA | pK18mobsacB carrying truncated bmoA (csal_1004) gene | This study |

| pK18mobsacB::ΔbmoB | pK18mobsacB carrying truncated bmoB (csal_1005) gene | This study |

| pBBR1MCS | Broad-host-range vector, Cmr | 55 |

| pBBR1MCS-bmoA | pBBR1MCS-2 carrying bmoA and its predicted native promoter region, Cmr | This study |

| pBBR1MCS-bmoB | pBBR1MCS carrying bmoB and its predicted native promoter region, Cmr | This study |

| pBBR1MCS-bmoA-bmoB | pBBR1MCS carrying bmoA and bmoB and their predicted native promoter regions, Cmr | This study |

| pACYCDuet1 | Dual protein expression vector, Cmr | Novagen |

| pACYC-bmoA | pACYCDuet1 carrying bmoA in MCS-1 under the control of the T7 promoter, Cmr | This study |

| pACYC-bmoB | pACYCDuet1 carrying bmoB in MCS-2 under the control of the T7 promoter, Cmr | This study |

| pACYC-bmoA-bmoB | pACYCDuet1 carrying bmoA in MCS-1 and bmoB in MCS-2 under the control of their respective T7 promoters, Cmr | This study |

| pET-28a(+) | Expression vector, Kmr | Novagen |

| pET28a-bmoA | pET28a carrying bmoA under the control of the T7 promoter (BmoA-His6) | This study |

| pET28a-bmoB | pET28a carrying bmoB under the control of the T7 promoter (His6-BmoB) | This study |

Cmr, chloramphenicol resistant; Kmr, kanamycin resistant.

DSMZ, German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures.

TABLE 4.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′)a | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| 1004uF | CTATGACATGATTACGAATTCACGATTTGCCTTATTACCACC (EcoRI) | Amplification of upstream flanking region of bmoA for construction of pK18mobsacB::ΔbmoA |

| 1004uR | GGATCCCCTTCATTGCACATCGTTCA (BamHI) | |

| 1004dF | GGATCCGAGCAGATCCATGAAGGCAT (BamHI) | Amplification of downstream flanking region of bmoA for construction of pK18mobsacB::ΔbmoA |

| 1004dR | ACGACGGCCAGTGCCAAGCTTCCTCGTGATAGTGGCTCATG (HindIII) | |

| 1005uF | CTATGACATGATTACGAATTCCCACCTTGACGTTATCCATC (EcoRI) | Amplification of upstream flanking region of bmoB for construction of pK18mobsacB::ΔbmoB |

| 1005uR | CATGACTCTTGAAGAAATTCTGGGTCATGGA | |

| 1005dF | GAATTTCTTCAAGAGTCATGTCGCCATCG | Amplification of downstream flanking region of bmoB for construction of pK18mobsacB::ΔbmoB |

| 1005dR | ACGACGGCCAGTGCCAAGCTTTGCCATCGTGTATGTGTCA (HindIII) | |

| sacB-F | CGACAACCATACGCTGAGAG | Amplification of partial sacB gene fragment |

| sacB-R | CGAAGCCCAACCTTTCATA | |

| 1004-test-F | TGAACGATGTGCAATGAAGG | Primers for screening of bmoA double-crossover mutant strains |

| 1004-test-R | GCATACCCCATTCAATGTCA | |

| 1005-test-F | TTCGTAGGTCCTGGAGTAGG | Primers for screening of bmoB double-crossover mutant strains |

| 1005-test-R | CGATGGCGACATGACT | |

| 04HF | GTCGACGGTATCGATAGGTATCCTCGCTCGGGCATT | Amplification of bmoA for construction of pBBR1MCS-bmoA |

| 04HR | CGCTCTAGAACTAGTGGAAAGTCTACCTGGTCGC | |

| 05HF | GTCGACGGTATCGATTGAATGGGGTATGCGTGA | Amplification of bmoB for construction of pBBR1MCS-bmoB |

| 05HR | CGCTCTAGAACTAGTAGTCACGCTGAGCGCCC | |

| 04EF | CATGCCATGGATCTGCTCGCCACAT (NcoI) | Amplification of bmoA gene for construction of pET28a-bmoA |

| 04ER | CCCAAGCTTGCCCTGAACGATGTGCAA (HindIII) | |

| 05EF | CGCCATATGACCCAGAATTTCTTCAATC (NdeI) | Amplification of bmoB gene for construction of pET28a-bmoB |

| 05ER | CGCGGATCCTCAGAACTCGATGGCGAC (BamHI) | |

| 04EF2 | CATGCCATGGATCTGCTCGCCACAT (NcoI) | Amplification of bmoA gene for construction of pACYC-bmoA |

| 04ER2 | CCCAAGCTTTCAGCCCTGAACGATGTG (HindIII) | |

| 05EF2 | CGCCATATGACCCAGAATTTCTTCAATC (NdeI) | Amplification of bmoB gene for construction of pACYC-bmoB |

| 05ER2 | TCGCGATCGTCAGAACTCGATGGCGAC (PvuI) |

Restriction sites are underlined and the restriction enzymes are in parentheses next to the sequence.

General DNA manipulations.

Total genomic DNA from C. salexigens and E. coli strains was prepared with the Ezup column bacteria genomic DNA extraction kit (Sangon, China), while plasmid DNA was isolated using the SanPrep column plasmid mini-preps kit (Sangon). All PCR amplifications were performed using the Pfu PCR MasterMix (TianGen, China), and the amplified DNA fragments were purified using the SanPrep column DNA gel extraction kit (Sangon). Colony PCR was performed as described previously (23).

Inactivation of bmoA (csal_1004) and bmoB (csal_1005).

The bmoA (Csal_1004) and bmoB (Csal_1005) single-gene in-frame deletion mutants of C. salexigens ZW4-1 were constructed by the allelic exchange method, as described previously (23). Briefly, the upstream and downstream regions of the target gene were PCR amplified from the genome of strain ZW4-1 (rifampin resistant [Rifr]) with the primer pairs listed in Table 4, fused together by splicing by overlapping extension PCR (SOE-PCR) (53), and cloned into the double-restriction enzyme-digested plasmid pK18mobsacB (kanamycin resistant [Kmr]) (54), which is nonreplicative in C. salexigens. The resultant plasmid pK18mobsacB::ΔbmoA, containing the mutant allele of bmoA with an internal 1,248-bp deletion, or pK18mobsacB::ΔbmoB, containing the mutant allele of bmoB with an internal 1,062-bp deletion, was first transformed into E. coli S17-1 competent cells and then mobilized into C. salexigens ZW4-1 (Rifr) via biparental mating. Single-crossover mutants were selected for growth on D5 plates with Rif and Km and verified by PCR with primers (sacB-F/sacB-R) to detect the backbone of the suicide vector. Double-crossover mutants were selected by growth on sucrose-containing D5 plates and verified by colony PCR with two primer sets (sacB-F/sacB-R and either 1004-test-F/1004-test-R [for bmoA] or 1005-test-F/1005-test-R [for bmoB]) to verify the absence of vector sequences and the presence of the mutant allele in the chromosome of C. salexigens. The resultant bmoA and bmoB deletion mutants of C. salexigens ZW4-1 were named strains 3043ΔbmoA and 3043ΔbmoB, respectively.

Complementation assays.

Complementation of C. salexigens strains 3043ΔbmoA and 3043ΔbmoB was performed by cloning full-length bmoA or bmoB along with its flanking DNA into the broad-host-range plasmid pBBR1MCS (chloramphenicol resistant [Cmr]) (55), in which the target gene is under the control of its native promoter, and the E. coli S17-1 strain was used to transfer the complementation plasmid into a C. salexigens deletion mutant by conjugation. For complementation of strain 3043ΔbmoA, a 1.7-kb fragment encompassing the wild-type bmoA and its surrounding DNA was amplified from the genomic DNA of ZW4-1 strain (Rifr) with the primers 04HF/04HR and cloned into the HindIII-BamHI sites of pBBR1MCS using the ClonExpress II one-step cloning kit (Vazyme, China); this yielded plasmid pBBR1MCS-bmoA, which contains the bmoA gene with its predicted native promoter (Fig. S3). For complementation of strain 3043ΔbmoB, a 1.4-kb fragment containing the wild-type bmoB and its surrounding DNA was amplified by PCR with the primers 05HF/05HR and ligated into the HindIII/BamHI sites of pBBBR1MCS, creating plasmid pBBR1MCS-bmoB (Fig. S3). DNA sequencing confirmed that the insertions in the plasmids were identical to the wild-type gene sequences. The complementation plasmid was transferred from E. coli S17-1 into the corresponding gene deletion mutants by conjugation, as described above. The gene complementary mutants were screened on D5 agar in the presence of Rif and Cm for strain 3043ΔbmoA carrying pBBR1MCS-bmoA and strain 3043ΔbmoB carrying pBBR1MCS-bmoB. The presence of plasmids in C. salexigens cells was verified by extraction of plasmids and gel electrophoresis. The abilities of complementation strains to use glucose, GB, or dimethylglycine as the sole carbon source were determined on C-M63 agar plates, while the wild type was used as the positive control and strains 3043ΔbmoA(pBBR1MCS) and 3043ΔbmoB(pBBR1MCS) as the negative controls.

Functional study of bmoA and bmoB in E. coli.

Both the bmoA and bmoB genes were amplified by PCR from the genomic DNA of strain ZW4-1 with the primers listed in Table 4. The bmoA PCR product was digested by NcoI and HindIII and inserted into the NcoI/HindIII sites of the MCS1 position in pACYCDuet-1 to generate the plasmid pACYC-bmoA, while the bmoB PCR product was digested by NdeI and PvuI and cloned into the NdeI/PvuI sites of the MCS2 position in pACYCDuet-1 to generate the plasmid pACYC-bmoB. For coexpression of BmoA and BmoB, the NdeI-PvuI fragment from pACYC-bmoB was ligated into NdeI-PvuI-digested pACYC-bmoA, generating the plasmid pACYC-bmoA-bmoB. The three recombinant plasmids were individually transformed into the competent E. coli BL21(DE3) cells, and single colonies of the positive transformants were picked and inoculated into LB broth containing Cm with shaking at 180 rpm and 37°C. When the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) reached 0.4 to 0.6, IPTG was added to induce protein expression (0.1 mM for BmoA, 0.05 mM for BmoB, and 0.1 mM for coexpression of BmoA and BmoB). After further incubation at 25°C for 40 h, the cells were harvested, washed twice with carbon-free C-M63 medium, and disrupted by sonication. The cell debris was removed by centrifugation, and the compatible solutes in the supernatant were extracted and detected by 13C NMR spectroscopy, as described below.

Extraction of intracellular solutes and 13C NMR analysis.

Cells were pelleted by centrifugation and washed twice with the same carbon-free growth medium, and cellular solutes were extracted as described by Martins and Santos (56). Freeze-dried extracts were dissolved in 0.5 ml of D2O and then placed into 5-mm nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) tubes. Natural-abundance 13C NMR spectra were recorded at 25°C with a Bruker Avance III HD 500 MHz superconducting FT NMR spectrometer at 125 MHz. 13C chemical shifts were referenced to an external dimethyl sulfoxide standard (δ = 40.6 ppm) and assigned by comparison with those of standard compounds.

Expression and purification of His-tagged recombinant proteins.

To express BmoA as a C-terminal histidine-tagged fusion protein, the coding region of bmoA gene was PCR amplified from ZW4-1 genomic DNA with the primers 04EF/04ER. The PCR products were digested with NcoI and HindIII, gel purified, and ligated into the same sites of pET28a, yielding pET28a-bmoA. To express BmoB as an N-terminal histidine-tagged fusion protein, the coding region of bmoB gene was PCR amplified with the primers 05EF/05ER, digested with NdeI and BamHI, and cloned into the same sites of pET28a, creating pET28a-bmoB. Subsequently, the expression vectors were separately transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) competent cells. E. coli BL21(DE3) cells carrying pET28a-bmoA or pET28a-bmoB were aerobically cultured in LB broth containing Km, 100 μM Na2S, and 50 μM NH4Fe(SO4)2 with constant shaking (180 rpm) at 37°C until the OD600 values reached 0.4 to 0.6; at that time, isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added (0.1 mM and 0.05 mM for BmoA and BmoB expression) to induce protein expression. After further incubation at 25°C for 16 h, cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed twice with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0), and resuspended in the same buffer. Cells were disrupted by sonication for 30 min (200 W, 3-s pulsing and 6-s resting), followed by centrifugation at 6,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The recombinant proteins in the supernatant were purified with the Ni-NTA Sefinose resin kit (Sango, China), according to the manufacturer's protocol, further concentrated to 3 to 5 ml using Amicon Ultra 10-kDa molecular weight cutoff (MWCO) filters (Merck), and analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). The concentrations of the purified enzymes were quantified by the Bradford method (57) using bovine serum albumin (fraction V) as the standard.

Determination of molecular weights.

The native molecular weights of BmoA-His6 and His6-BmoB were estimated by gel filtration chromatography on a Sephacryl S-200 high-resolution (HR) column (1.6 by 90 cm), which was calibrated with sweet potato β-amylase (molecular weight, 200,000), yeast alcohol dehydrogenase (150,000), bovine serum albumin (66,000), ovalbumin (43,000), and cytochrome c from horse heart (12,400). The column was preequilibrated and eluted with 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.0) containing 150 mM NaCl at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. The void volume (Vo) of the column was estimated using blue dextran (2,000 kDa), while the elution volume (Ve) for each protein was calculated from the midpoint of the peaks. The data were plotted in terms of log of molecular weight against Ve/Vo. The molecular weights of the subunits of purified enzyme were estimated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), as described previously (58).

Enzyme assays. (i) Flavin reductase activity assay.

The flavin reductase activity of His6-BmoB was monitored by measuring NADH consumption at 340 nm and calculated using the molar extinction coefficient of 6.22 mM−1 · cm−1. A typical reaction mixture contained 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0), 0.15 mM FAD, and 1.2 μM purified His6-BmoB in a final volume of 1 ml. The reactions were started by adding 0.2 mM NADH to the reaction mixture. An assay mixture without FAD was used as a blank. One unit of reductase activity was defined as the amount of enzyme catalyzing the oxidation of 1 μmol NADH per minute at 25°C under the assay conditions. To determine the substrate specificity of BmoB, NADPH, FMN, and riboflavin were employed as the substrates.

The kinetic parameters of BmoB were determined by incubating the protein (1.2 μM) with various concentrations of tested substrates (NADH, NADPH, FMN, FAD, or riboflavin), as indicated in Table 1, in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0) at 25°C. The absorption coefficients used in this study were the same as those described by Otto et al. (59). The kinetic experiments were performed with three different enzyme preparations, and apparent kinetic parameters were obtained using nonlinear regression analysis via the Michaelis-Menten equation in GraphPad Prism 5.

(ii) GB monooxygenase assay.

Glycine betaine monooxygenase activity was assayed by measuring the amount of formaldehyde produced with the Nash reagent, as described previously (60), with some modifications. The standard reaction mixture contained 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0), 2 mM FeSO4, 5 mM NADH, 10 μM FAD, 2 mM GB, 17 μM BomA-His6, and 3.4 μM His6-BmoB in a total volume of 1 ml. The reaction was started by adding NADH to the reaction mixture. After incubation at 30°C for 30 min with shaking, the reaction was stopped by addition of 0.1 ml of 75% (vol/vol) trichloroacetic acid, and denatured proteins were removed by centrifugation. The resultant supernatant was mixed with equal volume of Nash reagent and incubated for 50 min at 37°C for color development. Then, the absorbance was measured at 412 nm. One unit of activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to produce 1 nmol formaldehyde per minute under the assay conditions. Specific activity was defined as the unit per milligram of protein.

Flavin determination and quantification.

Noncovalent binding of the flavin cofactor present in BmoB was determined by trichloroacetic acid treatment, as described previously (61). Preparations of the purified His6-BmoB were boiled for 10 min to release the flavin and then centrifuged to remove the denatured protein. The resultant supernatant was further filtered across a 0.45-μm nitrocellulose membrane, subjected to an Agilent 1100 series HPLC system equipped with an Agilent Zorbax SB-Aq C18 column (250 by 4.6 mm, 5 μm particle size), and eluted with a mobile phase consisting of a mixture of 20 mM ammonium acetate dissolved in water (pH 6.0) (91%) and acetonitrile (9%) at a flow rate of 1 ml/min, as described by Petrusma et al. (62). The column temperature was maintained at 30°C, and the detection wavelength was set at 375 nm. The eluent was identified by comparing the retention time and UV-visible spectra to those of the authentic FMN (retention time, 8.87 min) and FAD (retention time, 11.65 min). The FAD content of His6-BmoB was determined spectrophotometrically by using the molecular absorption coefficient of ε450 = 11,300 M−1 · cm−1 for free FAD (63).

Analysis of the reaction products.

GB and dimethylglycine in vitro assays were measured by a HPLC system (Agilent 1100 series) with a Supelcosil LC-SCX column (25 cm by 4.6 mm, 5 μm; Supelco, Inc.), as described by Laryea et al. (64), with some modifications. The mobile phase was a 90% acetonitrile–10% choline aqueous solution (22 mM) at a flow rate of 1.5 ml · min−1. UV detection was set at a 254 nm wavelength. Under these assay conditions, the retention times of GB and dimethylglycine were determined to be 23.49 min and 21.18 min, respectively. Compounds were identified by comparison with the retention times and UV-visible spectra of authentic standards. Quantitation of GB and dimethylglycine in the reaction quench solution was accomplished by a comparison of the peak heights with those of external standards at known concentrations. The amount of hydrogen peroxide generated during the in vitro assays was measured using a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-coupled oxidation reaction, as described previously (65).

Effects of metal ions and EDTA on BMO activity.

The effects of metal ions and EDTA on BMO activity were determined by the addition of each metal ion (NaCl, KCl, FeSO4, MnSO4, CuSO4, ZnSO4, MgCl2, CaCl2, CoCl2, and AgNO3) or EDTA to the reaction mixture at a final concentration of 2 mM, and the enzyme activities were measured under standard conditions.

Determination of the content of iron and acid-labile sulfide.

The total iron (66) and acid-labile sulfide (67) contents of enzymes were determined colorimetrically with tripyridyl-s-triazine and N,N-dimethyl-p-phenylenediamine, respectively.

Sequence and phylogenetic analysis.

Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequence similarity searches were carried out using the BLAST program (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST). Multiple-sequence alignment analysis was performed with DNAMAN version 8.0. Phylogenetic trees of BmoA with the members in RO family were constructed using neighbor-joining algorithm in MEGA 7.0 (68). Confidence for tree topology was estimated based on 1,000 bootstrap replicates.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant 31070047) and the National College Student's Innovation Project (grant 200610435056).

We are grateful to R. M. Summers (University of Alabama, USA) for his technological assistance in the enzyme assays.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00377-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Welsh DT. 2000. Ecological significance of compatible solute accumulation by micro-organisms: from single cells to global climate. FEMS Microbiol Rev 24:263–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2000.tb00542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ziegler C, Bremer E, Krämer R. 2010. The BCCT family of carriers: from physiology to crystal structure. Mol Microbiol 78:13–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pao SS, Paulsen IT, Saier MH Jr. 1998. Major facilitator superfamily. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 62:1–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boscari A, Mandon K, Poggi M-C, Le Rudulier D. 2004. Functional expression of Sinorhizobium meliloti BetS, a high-affinity betaine transporter, in Bradyrhizobium japonicum USDA110. Appl Environ Microbiol 70:5916–5922. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.10.5916-5922.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen C, Malek AA, Wargo MJ, Hogan DA, Beattie GA. 2010. The ATP-binding cassette transporter Cbc (choline/betaine/carnitine) recruits multiple substrate-binding proteins with strong specificity for distinct quaternary ammonium compounds. Mol Microbiol 75:29–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06962.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nyyssölä A, Kerovuo J, Kaukinen P, von Weymarn N, Reinikainen T. 2000. Extreme halophiles synthesize betaine from glycine by methylation. J Biol Chem 275:22196–22201. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M910111199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nyyssölä A, Reinikainen T, Leisola M. 2001. Characterization of glycine sarcosine N-methyltransferase and sarcosine dimethylglycine N-methyltransferase. Appl Environ Microbiol 67:2044–2050. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.5.2044-2050.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oren A. 1990. Formation and breakdown of glycine betaine and trimethylamine in hypersaline environments. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 58:291–298. doi: 10.1007/BF00399342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Müller E, Fahlbusch K, Walther R, Gottschalk G. 1981. Formation of N,N-dimethylglycine, acetic acid, and butyric acid from betaine by Eubacterium limosum. Appl Environ Microbiol 42:439–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kortstee GJJ. 1970. The aerobic decomposition of choline by microorganisms. Arch Mikrobiol 71:235–244. doi: 10.1007/BF00410157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Časaitė V, Povilonienė S, Meškienė R, Rutkienė R, Meškys R. 2011. Studies of dimethylglycine oxidase isoenzymes in Arthrobacter globiformis cells. Curr Microbiol 62:1267–1273. doi: 10.1007/s00284-010-9852-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chlumsky LJ, Zhang L, Jorns MS. 1995. Sequence analysis of sarcosine oxidase and nearby genes reveals homologies with key enzymes of folate one-carbon metabolism. J Biol Chem 270:18252–18259. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.31.18252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boncompagni E, Osteras M, Poggi MC, le Rudulier D. 1999. Occurrence of choline and glycine betaine uptake and metabolism in the family Rhizobiaceae and their roles in osmoprotection. Appl Environ Microbiol 65:2072–2077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vargas C, Jebbar M, Carrasco R, Blanco C, Calderón MI, Iglesias-Guerra F, Nieto JJ. 2006. Ectoines as compatible solutes and carbon and energy sources for the halophilic bacterium Chromohalobacter salexigens. J Appl Microbiol 100:98–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White RF, Kaplan L, Birnbaum J. 1973. Betaine-homocysteine transmethylase in Pseudomonas denitrificans, a vitamin B12 overproducer. J Bacteriol 113:218–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith LT, Pocard JA, Bernard T, Le Rudulier D. 1988. Osmotic control of glycine betaine biosynthesis and degradation in Rhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol 170:3142–3149. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.7.3142-3149.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barra L, Fontenelle C, Ermel G, Trautwetter A, Walker GC, Blanco C. 2006. Interrelations between glycine betaine catabolism and methionine biosynthesis in Sinorhizobium meliloti strain 102F34. J Bacteriol 188:7195–7204. doi: 10.1128/JB.00208-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Waditee R, Incharoensakdi A. 2001. Purification and kinetic properties of betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase from Aphanothece halophytica. Curr Microbiol 43:107–111. doi: 10.1007/s002840010270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wargo MJ, Szwergold BS, Hogan DA. 2008. Identification of two gene clusters and a transcriptional regulator required for Pseudomonas aeruginosa glycine betaine catabolism. J Bacteriol 190:2690–2699. doi: 10.1128/JB.01393-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li S, Yu X, Beattie GA. 2013. Glycine betaine catabolism contributes to Pseudomonas syringae tolerance to hyperosmotic stress by relieving betaine-mediated suppression of compatible solute synthesis. J Bacteriol 195:2415–2423. doi: 10.1128/JB.00094-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fitzsimmons LF, Hampel KJ, Wargo MJ. 2012. Cellular choline and glycine betaine pools impact osmoprotection and phospholipase C production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 194:4718–4726. doi: 10.1128/JB.00596-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Copeland A, O'Connor K, Lucas S, Lapidus A, Berry KW, Detter JC, Del Rio TG, Hammon N, Dalin E, Tice H, Pitluck S, Bruce D, Goodwin L, Han C, Tapia R, Saunders E, Schmutz J, Brettin T, Larimer F, Land M, Hauser L, Vargas C, Nieto JJ, Kyrpides NC, Ivanova N, Göker M, Klenk HP, Csonka LN, Woyke T. 2011. Complete genome sequence of the halophilic and highly halotolerant Chromohalobacter salexigens type strain (1H11T). Stand Genomic Sci 5:379–388. doi: 10.4056/sigs.2285059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shao Y-H, Guo L-Z, Yu H, Zhao B-S, Lu W-D. 2017. Establishment of a markerless gene deletion system in Chromohalobacter salexigens DSM 3043. Extremophiles 21:839–850. doi: 10.1007/s00792-017-0946-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Daughtry KD, Xiao Y, Stoner-Ma D, Cho E, Orville AM, Liu P, Allen KN. 2012. Quaternary ammonium oxidative demethylation: X-ray crystallographic, resonance Raman, and UV-visible spectroscopic analysis of a Rieske-type demethylase. J Am Chem Soc 134:2823–2834. doi: 10.1021/ja2111898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kauppi B, Lee K, Carredano E, Parales RE, Gibson DT, Eklund H, Ramaswamy S. 1998. Structure of an aromatic-ring-hydroxylating dioxygenase-naphthalene 1,2-dioxygenase. Structure 6:571–586. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(98)00059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Calderón MI, Vargas C, Rojo F, Iglesias-Guerra F, Csonka LN, Ventosa A, Nieto JJ. 2004. Complex regulation of the synthesis of the compatible solute ectoine in the halophilic bacterium Chromohalobacter salexigens DSM 3043T. Microbiology 150:3051–3063. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27122-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reese MG. 2001. Application of a time-delay neural network to promoter annotation in the Drosophila melanogaster genome. Comput Chem 26:51–56. doi: 10.1016/S0097-8485(01)00099-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Galinski EA. 1995. Osmoadaptation in bacteria. Adv Microb Physiol 37:273–328. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2911(08)60148-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.May G, Faatz E, Villarejo M, Bremer E. 1986. Binding protein dependent transport of glycine betaine and its osmotic regulation in Escherichia coli K12. Mol Gen Genet 205:225–233. doi: 10.1007/BF00430432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee J, Simurdiak M, Zhao H. 2005. Reconstitution and characterization of aminopyrrolnitrin oxygenase, a Rieske N-oxygenase that catalyzes unusual arylamine oxidation. J Biol Chem 280:36719–36727. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505334200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eichhorn E, van der Ploeg JR, Leisinger T. 1999. Characterization of a two-component alkanesulfonate monooxygenase from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 274:26639–26646. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.38.26639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosche B, Tshisuaka B, Fetzner S, Lingens F. 1995. 2-Oxo-1,2-dihydroquinoline 8-monooxygenase, a two-component enzyme system from Pseudomonas putida 86. J Biol Chem 270:17836–17842. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.30.17836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cafaro V, Scognamiglio R, Viggiani A, Izzo V, Passaro I, Notomista E, Piaz FD, Amoresano A, Casbarra A, Pucci P, Di Donato A. 2002. Expression and purification of the recombinant subunits of toluene/o-xylene monooxygenase and reconstitution of the active complex. Eur J Biochem 269:5689–5699. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bill E, Bernhardt F-H, Trautwein AX. 1981. Mössbauer studies on the active Fe …[2Fe-2S] site of putidamonooxin, its electron transport and dioxygen activation mechanism. Eur J Biochem 121:39–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1981.tb06426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burnet M, Lafontaine PJ, Hanson AD. 1995. Assay, purification, and partial characterization of choline monooxygenase from spinach. Plant Physiol 108:581–588. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.2.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chaiyen P, Suadee C, Wilairat P. 2001. A novel two-protein component flavoprotein hydroxylase. Eur J Biochem 268:5550–5561. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2001.02490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lei B, Tu SC. 1998. Mechanism of reduced flavin transfer from Vibrio harveyi NADPH-FMN oxidoreductase to luciferase. Biochemistry 37:14623–14629. doi: 10.1021/bi981841+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bernhardt F-H, Bill E, Trautwein AX, Twilfer H. 1988. 4-Methoxybenzoate monooxygenase from Pseudomonas putida: isolation, biochemical properties, substrate specificity, and reaction mechanisms of the enzyme components. Methods Enzymol 161:281–294. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(88)61031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dumitru R, Jiang WZ, Weeks DP, Wilson MA. 2009. Crystal structure of dicamba monooxygenase: a Rieske nonheme oxygenase that catalyzes oxidative demethylation. J Mol Biol 392:498–510. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van der Geize R, Hessels GI, van Gerwen R, van der Meijden P, Dijkhuizen L. 2002. Molecular and functional characterization of kshA and kshB, encoding two components of 3-ketosteroid 9α-hydroxylase, a class IA monooxygenase, in Rhodococcus erythropolis strain SQ1. Mol Microbiol 45:1007–1018. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosche B, Tshisuaka B, Hauer B, Lingens F, Fetzner S. 1997. 2-Oxo-1,2-dihydroquinoline 8-monooxygenase: phylogenetic relationship to other multicomponent nonheme iron oxygenases. J Bacteriol 179:3549–3554. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.11.3549-3554.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burnet MW, Goldmann A, Message B, Drong R, El Amrani A, Loreau O, Slightom J, Tepfer D. 2000. The stachydrine catabolism region in Sinorhizobium meliloti encodes a multi-enzyme complex similar to the xenobiotic degrading systems in other bacteria. Gene 244:151–161. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(99)00554-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Karlsson A, Beharry ZM, Matthew Eby D, Coulter ED, Neidle EL, Kurtz DM Jr, Eklund H, Ramaswamy S. 2002. X-ray crystal structure of benzoate 1,2-dioxygenase reductase from Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1. J Mol Biol 318:261–272. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Batie CJ, Ballou DP, Correll CC. 1991. Phthalate dioxygenase reductase and related flavin-iron-sulfur containing electron transferases. Chem Biochem Flavoenzymes 3:543–556. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhu Y, Jameson E, Crosatti M, Schafer H, Rajakumar K, Bugg TD, Chen Y. 2014. Carnitine metabolism to trimethylamine by an unusual Rieske-type oxygenase from human microbiota. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:4268–4273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316569111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ertekin E, Konstantinidis KT, Tezel U. 2017. A Rieske-type oxygenase of Pseudomonas sp. BIOMIG1 converts benzalkonium chlorides to benzyldimethyl amine. Environ Sci Technol 51:175–181. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b03705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Correll CC, Batie CJ, Ballou DP, Ludwig ML. 1985. Crystallographic characterization of phthalate oxygenase reductase, an iron-sulfur flavoprotein from Pseudomonas cepacia. J Biol Chem 260:14633–14635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Capyk JK, Eltis LD. 2012. Phylogenetic analysis reveals the surprising diversity of an oxygenase class. J Biol Inorg Chem 17:425–436. doi: 10.1007/s00775-011-0865-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nam J-W, Nojiri H, Yoshida T, Habe H, Yamane H, Omori T. 2001. New classification system for oxygenase components involved in ring-hydroxylating oxygenations. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 65:254–263. doi: 10.1271/bbb.65.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pinto A, Tarasev M, Ballou DP. 2006. Substitutions of the “bridging” aspartate 178 result in profound changes in the reactivity of the Rieske center of phthalate dioxygenase. Biochemistry 45:9032–9041. doi: 10.1021/bi060216z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Parales RE, Parales JV, Gibson DT. 1999. Aspartate 205 in the catalytic domain of naphthalene dioxygenase is essential for activity. J Bacteriol 181:1831–1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Heckman KL, Pease LR. 2007. Gene splicing and mutagenesis by PCR-driven overlap extension. Nat Protoc 2:924–932. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schäfer A, Tauch A, Jäger W, Kalinowski J, Thierbach G, Pühler A. 1994. Small mobilizable multi-purpose cloning vectors derived from the Escherichia coli plasmids pK18 and pK19: selection of defined deletions in the chromosome of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Gene 145:69–73. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90324-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kovach ME, Elzer PH, Steven Hill D, Robertson GT, Farris MA, Roop RM II, Peterson KM. 1995. Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene 166:175–176. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00584-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Martins LO, Santos H. 1995. Accumulation of mannosylglycerate and di-myo-inositol-phosphate by Pyrococcus furiosus in response to salinity and temperature. Appl Environ Microbiol 61:3299–3303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bradford MM. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Laemmli UK. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Otto K, Hofstetter K, Rothlisberger M, Witholt B, Schmid A. 2004. Biochemical characterization of StyAB from Pseudomonas sp. strain VLB120 as a two-component flavin-diffusible monooxygenase. J Bacteriol 186:5292–5302. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.16.5292-5302.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kleeberg U, Klinger W. 1982. Sensitive formaldehyde determination with NASH's reagent and a ‘tryptophan reaction.’ J Pharmacol Methods 8:19–31. doi: 10.1016/0160-5402(82)90004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Siegel LM. 1978. Quantitative determination of noncovalently bound flavins: types and methods of analysis. Methods Enzymol 53:419–429. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(78)53046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]