Abstract

Introduction

Gender-related stereotypes of pain may account for some assessment and treatment disparities among patients. Among health care providers, demographic factors including gender and profession may influence the use of gender cues in pain management decision-making. The Gender Role Expectations of Pain Questionnaire was developed to assess gender-related stereotypic attributions of pain regarding sensitivity, endurance, and willingness to report pain, and has not yet been used in a sample of health care providers. The purpose of this study was to examine the presence of gender role expectation of pain among health care providers. It was hypothesized that health care providers of both genders would endorse gender stereotypic views of pain and physicians would be more likely than dentists to endorse these views.

Methods

One-hundred and sixty-nine providers (89 dentists, 80 physicians; 40% women) were recruited as part of a larger study examining providers’ use of demographic cues in making pain management decisions. Participants completed the Gender Role Expectations of Pain Questionnaire to assess the participant’s views of gender differences in pain sensitivity, pain endurance, and willingness to report pain.

Results

Results of repeated measures analysis of variance revealed that health care providers of both genders endorsed stereotypic views of pain regarding willingness to report pain (F(1,165)=34.241, P<0.001; d=0.479). Furthermore, female dentists rated men as having less endurance than women (F(1,165)=4.654, P=0.032; d=0.333).

Conclusion

These findings affirm the presence of some gender-related stereotypic views among health care providers and suggest the presence of a view among health care providers that men are underreporting their pain in comparison to women. Future work can refine the effects of social learning history and other psychosocial factors that contribute to gender and provider differences in pain management decisions.

Keywords: gender, pain, expectations, physicians, dentists

Introduction

Gender-related expectations regarding a patient’s pain presentation (eg, chronicity, reported severity, and pain behaviors), demographics, and level of psychological distress can influence a health care provider’s decision-making.1 For instance, experimental studies have found that health care providers and trainees tend to view women as more likely to exaggerate their pain and less likely to minimize or hide it.2 These biases appear to affect treatment recommendations, as male patients are less likely to receive psychosocial assessment or treatment for pain3,4 and women patients are less likely to receive more aggressive analgesic treatment.5,6

Equally important factors when examining gender differences in pain management are the characteristics of health care providers themselves. For example, male and female health care providers have been found to differ in their opioid-prescribing practices, the likelihood of recommending psychological interventions, and the use of patient distress as a clinical decision-making tool.7,8 Furthermore, health care providers are subject to gender role expectations regarding their clinical decision-making, with female health care providers generally expected to be more understanding and accepting of patient’s pain and its associated distress.8 Together, gender role expectations of the patient and health care provider may interact to influence pain management decisions. For example, studies have found that health care providers tend to provide more opioids to patients of the same gender.4,9,10

The study of the role of gender role expectations may provide valuable insight into mechanisms underlying pain management disparities. The Gender Role Expectations of Pain Questionnaire (GREP) is a standardized measure developed to assess gender-related stereotypic attributions of pain sensitivity, endurance, and willingness to report pain.11 Studies using the GREP in undergraduate samples have found that both men and women tend to affirm gender-related stereotypic attributions (ie, women are more willing to report pain, more sensitive to pain, and less able to endure pain than men).11,12 The GREP has not yet been used in a health care provider sample, and information from the GREP may provide valuable input into how gender-related stereotypic attributions in health care providers may contribute to pain assessment and treatment disparities.

Although health care providers are trained with the goal of being “neutral providers” (ie, providing clinical care without regard to patient gender, race, ethnicity, and so on), they are subject to the same social influences that foster gender/gender-related biases in the general population.13 Dentists and physicians see many patients with a primary complaint of pain, yet receive relatively little formal training in pain management and rely on simple cues for pain management decisions.14–17 Furthermore, because dentists and physicians differ in the types of pain conditions they typically treat, there may be cross-professional differences in how stereotypic cues are utilized when making pain decisions. One study using a virtual human paradigm found that, compared to dentists, physicians weighed age cues more heavily when making pain management decisions.18 Physicians tend to see a higher volume of patients as well as more diverse, comorbid pain conditions compared to dentists, and as a result, they may rely more on simple cues (eg, gender, age, and race) when making clinical decisions.18 Further study of cross-professional differences in biased clinical decision making may provide valuable insight into mechanisms of pain management disparities.

The aim of this study was to examine the effect of gender and profession of the health care provider on the extent to which they endorsed gender stereotypic views of pain, utilizing a sample of dentists and physicians. We hypothesized that the overall sample of health care providers would endorse the gender stereotypic views of pain (ie, women are more sensitive and willing to disclose pain and less able to endure pain compared to men). We also hypothesized that there would not be a gender difference among health care providers such that both men and women would endorse stereotypic views. Finally, we hypothesized that physicians would be more likely to endorse these views given evidence that they may rely more heavily on patients’ demographic cues when making pain treatment decisions.18

Participants and methods

Participants

Dentists and physicians were identified using records from Florida’s Department of Business and Professional Regulations and were contacted via direct mailings and electronic listservs advertising a web-based study on assessment and clinical decision-making in pain management; individuals who expressed interest were directed to a secure website to complete the study. Participants were included if they were an adult aged 18 years or older and currently in clinical practice.

Procedure

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Florida. All participants provided written informed consent prior to data collection. Data were collected as part of a larger study utilizing video vignettes of virtual human patients to examine assessment and clinical decision-making in pain management. As previously described,7,18 dentists and physicians were invited to participate via direct mailings and professional listservs. Participants who expressed interest were directed to a secure website to complete the study. Participants completed an informed consent document, followed by the demographic and GREP questionnaires, and then the remainder of the study. Following study completion, participants were compensated $50 for their time.

Demographic questionnaire

Participants completed a brief demographic questionnaire assessing gender, race, age, area of practice (ie, medical and dental), and years of professional experience.

GREP

The GREP consists of twelve 10 cm visual analog scales (VAS) that assess the participant’s views of gender differences in pain sensitivity, pain endurance, and willingness to report pain. Each item asks participants to place a mark on the VAS to estimate how the typical woman is compared with the typical man (eg, “compared to the typical woman, the typical man’s sensitivity is”) and how the typical man is compared with the typical woman, anchored from “far less” to “far greater”. Each item contains the anchors far less on the left side and far greater on the right, with a score of 50, suggesting no difference between men and women; for example, a rating of 65 on the item compared to the typical woman, the typical man’s sensitivity is would indicate that the participant believes that the typical man is more sensitive to pain than the typical woman. The GREP also assesses participants’ views of their own pain sensitivity, pain endurance, and willingness to report pain compared to the typical man and woman; for this study, the “self ” items were omitted from analysis and the remaining six items were used. Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for each question on the GREP questionnaire used in this analysis. The GREP demonstrates good internal consistency and fair-to-good test–retest reliability.11 As expected,11,19 negative correlations were found between items reflecting the opposite gender role; in this study, “sensitivity” items correlated at −0.483, “endurance” items correlated at −0.550, and “willingness” items correlated at −0.447.

Table 1.

GREP items’ mean and standard deviation by gender and profession

| GREP item | Profession

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dentists

|

Physicians

|

||||||

| Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | ||

| Sensitivity | 3. Typical man compared to typical woman | 43.88 (22.64) | 47.22 (28.37) | 45.08 (24.75) | 53.30 (19.70) | 47.83 (20.29) | 50.84 (19.70) |

| 4. Typical woman compared to typical man | 48.98 (21.93) | 43.19 (25.28) | 46.90 (23.22) | 46.73 (22.99) | 49.36 (22.59) | 47.91 (22.71) | |

| Endurance | 7. Typical man compared to typical woman | 50.49 (20.58) | 39.41 (25.72) | 46.51 (23.05) | 44.43 (21.91) | 50.50 (23.45) | 47.16 (22.67) |

| 8. Typical woman compared to typical man | 46.56 (20.37) | 55.75 (23.52) | 49.87 (21.87) | 52.20 (22.53) | 51.92 (22.60) | 52.08 (22.42) | |

| Willingness | 11. Typical man compared to typical woman | 34.25 (21.11) | 37.25 (25.79) | 35.33 (22.81) | 40.02 (25.00) | 37.17 (24.27) | 38.74 (24.56) |

| 12. Typical woman compared to typical man | 59.40 (22.18) | 53.66 (27.64) | 57.34 (24.28) | 51.50 (20.95) | 58.50 (23.45) | 54.65 (22.24) | |

Abbreviation: GREP, Gender Role Expectations of Pain Questionnaire.

Statistical analyses

All data analyses were performed using SPSS version 24.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive analyses were conducted to summarize the demographic and background characteristics of the sample as well as GREP responses. Missing data were replaced with the group mean value resulting in the replacement of 0.2% of GREP responses. Two (gender: male and female) by two (profession: dentists and physicians) by two (GREP item pair) repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to examine effects of gender and profession type on gender-related stereotypic attributions regarding pain sensitivity, endurance, and willingness to report. Separate ANOVA was run for each GREP factor (ie, pain sensitivity, pain endurance, and willingness to report pain). For example, one ANOVA examining pain sensitivity included the within-subjects factors of ratings for GREP item 4 (compared to the typical man, the typical woman’s sensitivity to pain is) and GREP item 3 (compared to the typical woman, the typical man’s sensitivity to pain is), with profession and gender as between-subjects factors. Effect sizes are reported as Cohen’s d adjusted for the dependence of means on an as-needed basis.20 Sphercity was assessed using the Mauchly test and was not violated across all ANOVAs (P>0.05).

Results

Demographics and professional characteristics

The final sample included 169 health care providers (89 dentists and 80 physicians; 40% women). Given that health care providers were contacted via direct mailings and professional listservs, the exact response rate for invitations to participate in the study could not be calculated. Gender distribution did not differ significantly across profession. The mean age was 45.60 years (SD=13.73). One hundred and fifteen (68.9%) participants were identified as Caucasian, 10 (5.9%) as Black, 11 (6.5%) as Hispanic, 22 (13.0%) as Asian, and 9 (5.3%) as another race or multiple races (2 individuals did not provide this information [no race reported]). Chi-squared and independent sample t-tests performed on relevant variables revealed a significant gender differences in years of professional experience (t=−4.388, P<0.001), with men having a greater number of years of experience (Mmen=19.317 years) compared to women (Mwomen=10.308). There was no significant difference in profession between genders (χ2=1.433, P>0.05). Table 2 presents mean and standard deviation of demographic variables.

Table 2.

Demographic and professional characteristics of study sample (N=169)

| Variables | Mean (SD)/percentage |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 45.60 (13.73) |

| Professional experience (years) | 15.69 (13.78) |

| Gender (female) | 40.2 |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 68.0 |

| Asian | 13.0 |

| Hispanic | 6.5 |

| Black | 5.9 |

| Others | 5.3 |

| Dental specialty | |

| General dentistry | 62.9 |

| Orthodontics | 12.4 |

| Operative dentistry | 6.7 |

| Periodontics | 5.6 |

| Endodontics | 3.4 |

| Others/not specified | 9.0 |

| Medical specialty | |

| Internal medicine | 26.3 |

| Primary care | 18.8 |

| Surgery | 12.5 |

| Anesthesiology | 7.5 |

| Obstetrics/gynecology | 6.3 |

| Emergency medicine | 3.8 |

| Neurology | 3.8 |

| Psychiatry | 2.5 |

| Others/not specified | 18.5 |

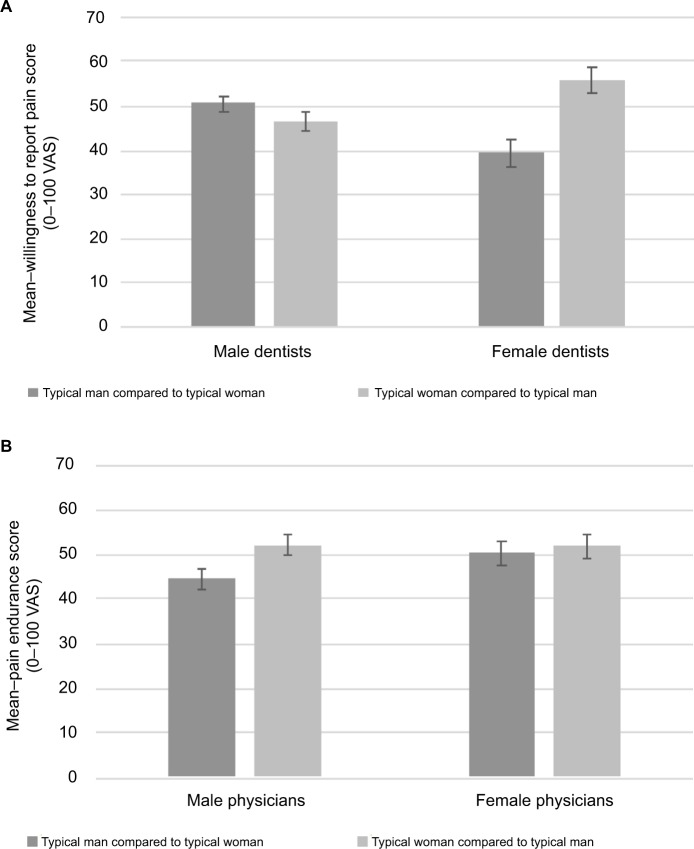

Willingness to report pain

Both men and women believed that the typical man was less willing to report pain than the typical woman (F(1,165)=34.241, P<0.001; d=0.479) (Figure 1). ANOVA revealed that no main effects were found on the gender (F(1,165)=0.034, P>0.05; d=0.000) or profession (F(1,165)=0.120, P>0.05; d=0.063) of the health care provider. No significant interactions were found between gender and profession of the health care provider (P>0.05) regarding beliefs about willingness to report pain.

Figure 1.

Ratings of willingness to report pain by provider’s gender.

Note: Error bars represent standard errors.

Abbreviation: VAS, visual analog scale.

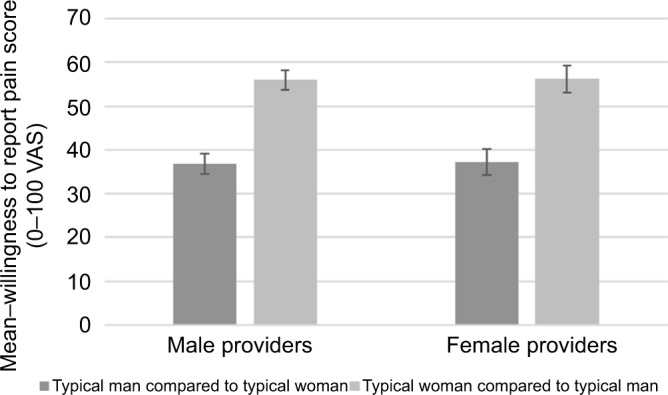

Pain endurance

Participants as a whole reported no significant differences between the typical man and woman with regard to pain endurance (F(1,165)=3.063, P>0.05; d=0.104). The main effects of neither gender (F(1,165)=0.334, P>0.05; d=0.090) nor profession (F(1,165)=1.036, P>0.05; d=0.1554) of the health care provider were statistically significantly associated with gender-related expectations of pain endurance. A profession by gender interaction was found for the health care provider (F(1,165)=4.654, P=0.032; d=0.333), with female dentists rated men as having less pain endurance than women (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Ratings of pain endurance by provider gender in (A) dentists and (B) physicians.

Note: Error bars represent standard errors.

Abbreviation: VAS, visual analog scale.

Sensitivity to pain

Analyses indicated that participants did not rate the typical man and typical woman as different with regard to pain sensitivity (F(1,165)=0.103, P>0.05; d=0.011). Furthermore, no main effects or interactions achieved significance (P>0.05).

Discussion

Studies applying the GREP have primarily recruited undergraduate students, who were found to use stereotypic pain-related attributions.11,21 The primary goal of this study was to explore GREP among a sample of practicing health care professionals as these expectations may influence pain management decision-making. Furthermore, this study is the first to evaluate whether pain-related expectations may differ based on profession and gender of the health care provider. We hypothesized that the beliefs of health care providers would be consistent with stereotypic views of gender differences in pain and both genders would endorse these stereotypes. We also hypothesized that among health care providers, physicians would be more likely to endorse such stereotypic views.

Overall, we found partial support for our hypotheses. Participants of both genders and professions endorsed the belief that women were more likely to disclose their pain to a health care provider than men, which is consistent with past GREP studies using an undergraduate sample.11,12 Previous literature suggests that health care providers tend to view women as more likely to exaggerate their pain.2 With this, it is possible that gender differences in analgesic treatment could be attributed to a stereotypic view that men are underreporting their pain in comparison to women and thus should receive more aggressive treatment. Overall, there was no significant overall main effect of profession on stereotypic views of gender differences in pain. However, we did identify a profession by gender interaction, such that compared to female physicians and men in both professions, female dentists rated men as having less pain endurance compared to men. Previous studies suggest that men seek dental care less frequently than women.22,23 Thus, men may delay treatment until symptoms are of relatively greater severity than women, resulting in exaggerated pain response. However, it is currently unclear why this effect might be reflected specifically in the responses of female vs male dentists. Our hypothesis that physicians would be more likely to endorse gender-related expectations of pain was not supported. While physicians have been found to weight age-related cues more strongly than dentists while making pain management decisions,18 gender as a cue may be equally used in both physicians and dentists. No significant expectations of gender differences in pain sensitivity were detected. These findings are at odds with previous GREP studies using nonprovider samples showing that both men and women perceive men as having greater endurance and less sensitivity to pain11,19,21 and may account for some of the variability in pain management practices for male and female patients. Studies exploring pain assessment disparities largely suggest that women are at increased risk of having their pain undertreated relative to men,24,25 while other studies find that women are more likely to receive prescription analgesics than men.26,27 Such differences may be accounted for higher pain reporting among women.28

In general, these results support gender role theories, suggesting that men and women are socialized differently and subsequently have varying expectations relative to pain perception.29,30 Additionally, this study is the first of the authors’ knowledge to extend the application of the GREP to a sample of practicing health care professionals. Results of the current study suggest that practicing health care providers may be subject to some similar gender-related biases as seen in the general population, which are affected by provider type and gender. This study also provides support for the use of GREP-related constructs in future investigations exploring differences among various health care providers’ gender biases related to pain perception.

Furthermore, findings of the current study indicate that, within and between professions, health care providers may be socialized to perceive pain differently based on their gender. Both dentists and physicians frequently provide care to patients presenting with a primary complaint of pain but will differ in the type of pain conditions they treat. Thus, differences in pain education and professional experience likely exist between professions and may account for the cross-professional differences found in this study. Discrepancies in gender- and provider-stereotyped pain expectations have received little attention in pain perception literature, and current findings may reflect external factors that have not been investigated fully in previous studies. Further investigation of provider expectations of pain in the context of endurance among diverse samples of health care providers and continued research on the clinical implications’ inconsistent practices that may have on patient care is warranted.

Biological mechanisms are recognized to at least partially account for gender differences in pain responding.31 However, we maintain that there are significant contributions unaccounted for biological differences between men and women. Experimental manipulation of gender role expectations has been shown to eliminate differences in pain report between men and women, strongly supporting the role of gender in gender differences.32 Sex and gender differences in pain also integrate social learning histories and child-rearing practices.33–35 These factors differ systematically between men and women and also vary across and within provider profession. Among patients, differences in gender-related expectations, pain endurance, sensitivity, and willingness to report pain may play a larger role in health care seeking behaviors and the type of health care received.

Study strengths and limitations

The current study represents an important step in addressing disparities in pain by virtue of its inclusion of a sample of health care providers (ie, dentists and physicians) whose professional responsibilities include direct pain management. This method allowed us to examine profession and gender differences in both general pain expectations and in pain perception. Knowledge of group differences could promote individual provider awareness of patient factors that are likely to influence their clinical decisions.

Conversely, our sample was limited to physicians and dentists and may not be generalizable to other health care providers (eg, nurses or physical therapists). However, our findings are similar to previous studies; sampling other populations, including undergraduates, which suggests the attitudes and expectations measured by the GREP, may be largely consistent across populations.11,12 Future investigations using the GREP should employ designs that also measure social learning history and its effect on gender and provider pain perception, for example, exposure to pain models.33 Additional studies further examining this relationship are likely to account for other unknown psychosocial factors (eg, fatigue, anxiety, and training experiences) that contribute to gender and health care provider differences in pain expectations, experiences, and reporting.

Conclusion

There are several potential clinical implications of the current study. First, the finding that health care professionals tend to hold some similar stereotypic gender attributions as the general population suggests that further work needs to be done in reducing biases in health care professionals;13 however, given that these professionals do not hold all of the same stereotypes as the general population, some education and experiences may serve to reduce some bias. These data also provide impetus for future investigations of the influence of GREP on pain management decisions. Additionally, it was found that GREP varies by provider type and gender, especially regarding ability to tolerate pain (ie, pain endurance). The GREP may help researchers better understand why and how these potential demographic variables might factor into decisions made about pain. It is interesting that gender stereotypes related to pain perception persist, despite recent societal movement toward less traditional gender roles (eg, income and work/home responsibilities).36 Taken together, GREP appear well established among health care providers. These findings suggest the need for studies examining the effectiveness of pain education in health care training and how such biases may develop. With such information, empirically based educational efforts can be developed, aimed at reducing provider biases related to pain management and improving the quality of care for patients experiencing pain.

Perspective

Results suggest that health care providers tend to hold the same stereotypic gender-related pain attributions as the general population. The GREP questionnaire is sensitive to gender-related stereotypic views among health care providers and could be used in future work to examine mechanisms of gender and provider differences in pain assessment and treatment.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported in part by a grant from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research to MER (R01DE013208).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Tait RC, Chibnall JT, Kalauokalani D. Provider judgments of patients in pain: seeking symptom certainty. Pain Med. 2009;10(1):11–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2008.00527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schafer G, Prkachin KM, Kaseweter KA, Williams AC. Health care providers’ judgments in chronic pain: the influence of gender and trustworthiness. Pain. 2016;157(8):1618–1625. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.LeResche L. Defining gender disparities in pain management. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(7):1871–1877. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1759-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Safdar B, Heins A, Homel P, et al. Impact of physician and patient gender on pain management in the emergency department – a multicenter study. Pain Med. 2009;10(2):364–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2008.00524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen EH, Shofer FS, Dean AJ, et al. Gender disparity in analgesic treatment of emergency department patients with acute abdominal pain. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15(5):414–418. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siddiqui A, Belland L, Rivera-Reyes L, et al. A multicenter evaluation of the impact of sex on abdominal and fracture pain care. Med Care. 2015;53(11):948–953. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bartley EJ, Boissoneault J, Vargovich AM, et al. The influence of health care professional characteristics on pain management decisions. Pain Med. 2015;16(1):99–111. doi: 10.1111/pme.12591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernardes SF, Costa M, Carvalho H. Engendering pain management practices: the role of physician sex on chronic low-back pain assessment and treatment prescriptions. J Pain. 2013;14(9):931–940. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weisse CS, Sorum PC, Dominguez RE. The influence of gender and race on physicians’ pain management decisions. J Pain. 2003;4(9):505–510. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weisse CS, Sorum PC, Sanders KN, Syat BL. Do gender and race affect decisions about pain management? J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(4):211–217. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016004211.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robinson ME, Riley JL, Myers CD, et al. Gender role expectations of pain: relationship to sex differences in pain. J Pain. 2001;2(5):251–257. doi: 10.1054/jpai.2001.24551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wandner LD, Scipio CD, Hirsh AT, Torres CA, Robinson ME. The perception of pain in others: how gender, race, and age influence pain expectations. J Pain. 2012;13(3):220–227. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zestcott CA, Blair IV, Stone J. Examining the presence, consequences, and reduction of implicit bias in health care: a narrative review. Group Process Intergroup Relat. 2016;19(4):528–542. doi: 10.1177/1368430216642029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alonso AA, Heima M, Lang LA, Teich ST. Dental students’ perceived level of competence in orofacial pain. J Dent Educ. 2014;78(10):1379–1387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaskin DJ, Richard P. The economic costs of pain in the United States. J Pain. 2012;13(8):715–724. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loeser JD, Schatman ME. Chronic pain management in medical education: a disastrous omission. Postgrad Med. 2017;129(3):332–335. doi: 10.1080/00325481.2017.1297668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pinto A, Khalaf M, Miller CS. The practice of oral medicine in the United States in the twenty-first century: an update. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2015;119(4):408–415. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2014.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boissoneault J, Mundt JM, Bartley EJ, Wandner LD, Hirsh AT, Robinson ME. Assessment of the influence of demographic and professional characteristics on health care providers’ pain management decisions using virtual humans. J Dental Educ. 2016;80(5):578–587. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wise EA, Price DD, Myers CD, Heft MW, Robinson ME. Gender role expectations of pain: relationship to experimental pain perception. Pain. 2002;96(3):335–342. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(01)00473-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morris SB, DeShon RP. Combining effect size estimates in meta-analysis with repeated measures and independent-groups designs. Psychol Methods. 2002;7(1):105. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robinson ME, Wise EA, Gagnon C, Fillingim RB, Price DD. Influences of gender role and anxiety on sex differences in temporal summation of pain. J Pain. 2004;5(2):77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee W, Kim S-J, Albert JM, Nelson S. Community factors predicting dental utilization among older adults. J Am Dental Assoc. 2014;145(2):150–158. doi: 10.14219/jada.2013.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Hara B, Caswell K. Health status, health insurance, and medical services utilization: 2010. Curr Pop Rep. 2012;2012:70–133. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Calderone KL. The influence of gender on the frequency of pain and sedative medication administered to postoperative patients. Sex Roles. 1990;23(11):713–725. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cleeland CS, Gonin R, Hatfield AK, et al. Pain and its treatment in outpatients with metastatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(9):592–596. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199403033300902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pokela N, Simon Bell J, Lihavainen K, Sulkava R, Hartikainen S. Analgesic use among community-dwelling people aged 75 years and older: a population-based interview study. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2010;8(3):233–244. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sadowski CA, Carrie AG, Grymonpre RE, Metge CJ, John P. Access and intensity of use of prescription analgesics among older Manitobans. Can J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;16(2):e322–e330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raftery KA, Smith-Coggins R, Chen AH. Gender-associated differences in emergency department pain management. Ann Emerg Med. 1995;26(4):414–421. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(95)70107-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bernardes SF, Keogh E, Lima ML. Bridging the gap between pain and gender research: a selective literature review. Eur J Pain. 2008;12(4):427–440. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Myers CD, Riley JL, Robinson ME. Psychosocial contributions to sex-correlated differences in pain. Clin J Pain. 2003;19(4):225–232. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200307000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bartley EJ, Palit S. Gender and pain. Curr Anesthesiol Rep. 2016;6(4):344–353. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robinson ME, Gagnon CM, Riley JL, Price DD. Altering gender role expectations: effects on pain tolerance, pain threshold, and pain ratings. J Pain. 2003;4(5):284–288. doi: 10.1016/s1526-5900(03)00559-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boissoneault J, Bunch JR, Robinson M. The roles of ethnicity, sex, and parental pain modeling in rating of experienced and imagined pain events. J Behav Med. 2015;38(5):809–816. doi: 10.1007/s10865-015-9650-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koutantji M, Pearce SA, Oakley DA. The relationship between gender and family history of pain with current pain experience and awareness of pain in others. Pain. 1998;77(1):25–31. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00075-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McGrath PJ, McAlpine L. Psychologic perspectives on pediatric pain. J Pediatr. 1993;122(5):S2–S8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(11)80002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Development of ECA . Employment Outlook. Paris: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development; 2008. [Google Scholar]