Abstract

RNA 3′ polyadenylation is known to serve diverse purposes in biology, in particular, regulating mRNA stability and translation. Here we determined that, upon exposure to high levels of the intercalating agent ethidium bromide (EtBr), greater than those required to suppress mitochondrial transcription, mitochondrial tRNAs in human cells became polyadenylated. Relaxation of the inducing stress led to rapid turnover of the polyadenylated tRNAs. The extent, kinetics and duration of tRNA polyadenylation were EtBr dose-dependent, with mitochondrial tRNAs differentially sensitive to the stress. RNA interference and inhibitor studies indicated that ongoing mitochondrial ATP synthesis, plus the mitochondrial poly(A) polymerase and SUV3 helicase were required for tRNA polyadenylation, while polynucleotide phosphorylase counteracted the process and was needed, along with SUV3, for degradation of the polyadenylated tRNAs. Doxycycline treatment inhibited both tRNA polyadenylation and turnover, suggesting a possible involvement of the mitoribosome, although other translational inhibitors had only minor effects. The dysfunctional tRNALeu(UUR) bearing the pathological A3243G mutation was constitutively polyadenylated at a low level, but this was markedly enhanced after doxycycline treatment. We propose that polyadenylation of structurally and functionally abnormal mitochondrial tRNAs entrains their PNPase/SUV3-mediated destruction, and that this pathway could play an important role in mitochondrial diseases associated with tRNA mutations.

INTRODUCTION

RNA 3′ polyadenylation has been reported to serve many roles in biology, with a distinction usually drawn between eukaryotes, where poly(A) is considered to play a positive role, facilitating nuclear export, stability and translation, and prokaryotes, where poly(A) is typically used as a tag to mark RNAs for degradation (reviewed in (1–3)). In eukaryotic organelles, notably chloroplasts, the bacterial principle of poly(A)-dependent RNA degradation prevails, although poly(A) plays a more ambiguous and often taxon- or even gene-specific role in mitochondria (3–6). In metazoan mitochondria, polyadenylation has been variously inferred to promote either mRNA turnover or stabilization (7–11), translation (9,10), tRNA maturation and/or repair (11,12) and to play a role, most likely an indirect one, in the sensitivity of nuclear DNA to double-strand breaks induced by ionizing radiation (13).

The dichotomous effects of 3′ poly(A) on metazoan mitochondrial mRNAs (stabilization versus destabilization) appear to be transcript-specific, with some stabilized but others destabilized by the inhibition of polyadenylation (8,10,14,15). The addition of A residues is also formally necessary for the creation of some UAA stop codons (16). The enzyme responsible for the synthesis of the poly(A) tails of mitochondrial mRNAs is the mitochondrial poly(A) polymerase (mtPAP, product of the PAPD1 gene). mtPAP may also be involved in the oligouridylation of histone mRNAs in the cytoplasm at the termination of S-phase (17,18). The degradation of human mitochondrial RNAs tagged with poly(A) is catalyzed by the components of the mitochondrial ‘degradosome’, namely SUV3 helicase (SUV3L1 gene product) and polynucleotide phosphorylase (PNPase, PNPT1 gene product, (15,19)). Degradation is believed to initiate when this complex interacts with unfolded poly(A) tails: thus, in the absence of SUV3 function, abnormal polyadenylated RNAs accumulate (20). Oligoadenylated tRNAs are detected when the processing or surveillance enzyme PDE12 is knocked down (12,21). Low level adenylation of misprocessed or truncated RNAs, including tRNAs, has been reported even in control cells (7).

Polyadenylation of tRNAs has been documented in bacteria, under the abnormal conditions of deficiency of tRNA processing enzymes (22,23) or deregulation of the poly(A) polymerase PAP I (23), leading to tRNA destruction and severely impaired protein synthesis. Defective tRNAs are tagged for degradation by polyadenylation in Escherichia coli (24) and eukaryotic nuclei (25). Polyadenylated tRNAs have also been reported in chloroplasts (26), although their physiological meaning is unknown.

In this study, we investigated the effects of ethidium bromide (EtBr), a DNA-intercalating agent that suppresses mitochondrial transcription. EtBr also intercalates into RNA, including tRNA (27), but this intercalation is restricted by the adoption of tertiary structures. In high-salt conditions tRNAs retain their native L-form structure, and are typically able to bind about tenfold less EtBr than when the tertiary structure is disturbed (28,29), with a preferred binding site at the base of the acceptor stem (28,30).

In previous studies, we (31) and others (32) have used EtBr at doses of up to 250 ng/ml to suppress mitochondrial transcription, resulting in the rapid disappearance of mitochondrial mRNAs and the gradual decay of the more stable mitochondrial rRNAs and tRNAs. Noting that higher doses of EtBr should intercalate more effectively into tRNAs, thus distorting their structure, we investigated the effects on mitochondrial tRNA metabolism of subjecting cells to tenfold greater concentrations of the drug than those used previously. Under these conditions, we revealed an unexpected propensity of mitochondrial tRNAs to acquire long poly(A) tails. After withdrawal of the EtBr, polyadenylated tRNAs were rapidly degraded, following a lag phase. We propose that this represents a mitochondrial surveillance system for abnormal tRNAs, similar to the tRNA quality-control process previously documented in bacteria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and culture

Previously described cell lines were as follows: 143B osteosarcoma cybrid cell lines homoplasmic for wild-type mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA; clone 43) or the 7472insC mutation (clone 47) (33,34), A549 lung carcinoma cells and the GT cybrid cell line derived from the A549 background, containing both np 3243 and np 12300 mutant mtDNA (35). Cells were routinely cultured in DMEM with or without uridine and pyruvate as described previously (34).

Oligonucleotides and reagents

Custom-designed DNA oligonucleotides were purchased from DNA Technology (Aarhus, Denmark). Their sequences and other relevant information are shown in Supplementary Table S1. Inhibitors used in polyadenylation assays at the final concentrations shown in figures and legends were cordycepin (3′ deoxyadenosine), CCCP, doxycycline, oligomycin (mixture A, B, C), or thiamphenicol (all from Sigma), or puromycin (InvivoGen). Antibodies were from Abcam: anti-mtPAP (ab154555, used at 1:2000); anti-PDE12 (ab87738, 1:500); anti-PNPT1 (PNPase, ab96176, 1:2000) and anti-SUV3L1 (SUV3, ab176854, 1:2000). Anti-GAPDH antibody was from Cell Signaling Technology (14C10, #2118, 1:3000), anti-β-actin from Santa Cruz (C4, sc-47778, 1:200) and HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (111-035-144) and goat anti-mouse (115-035-146) secondary antibodies (1:20 000) were from Jackson ImmunoResearch Inc., the latter being used for detection of the anti-actin signal.

RNA analysis

Total RNA was extracted from cells using the Trizol reagent (Life Technologies) under manufacturer's recommended conditions. RNA was fractionated on 12% polyacrylamide (PAGE)-7 M urea/TBE gels, electroblotted to Zeta-Probe or Zeta-probe GT membranes (BioRad), and hybridized to gene-specific oligoprobes as described previously (34,35) or using Rapid-hyb buffer (GE Healthcare). Signals were visualized by sensitive X-ray film or, where indicated in legends, by phosphorimaging (Typhoon™ imaging system, GE Healthcare). For aminoacylation analyses, total RNA was dissolved on ice in 0.1 M sodium acetate, pH 5.2 and fractionated on acidic 6.5% PAGE-7 M urea gels essentially as described previously (36,37). Samples were deacylated by heating for 10 min at 75°C followed by 30 min at 37°C in 1.5 volumes of 0.5 M Tris–HCl, pH 9.0. To analyze the primary structure of tRNA products in EtBr-treated cells, total RNA was isolated, tRNAs deacylated and circularized by T4 RNA ligase (MBI Fermentas) as described (38), reverse-transcribed with oligonucleotides cser1 or cleu1 and PCR-amplified using oligonucleotides cser1 and cser2 for analysis of tRNASer(UCN) or cleu1 and cleu2 for analysis of tRNALeu(UUR), essentially as described previously (31). The high-molecular weight tRNALeu(UUR) products induced by doxycycline treatment were gel-extracted, circularized and amplified similarly. PCR products were cloned (TOPO TA cloning kit, Invitrogen) and inserts Sanger-sequenced using M13 forward primer and standard dye-terminator technology as described previously (39).

Analysis of tRNA response to EtBr

Cells were seeded at equal densities on 6 cm plates, giving 70–80% confluence, 14–16 h before the experiments. They were then incubated in fresh medium containing different concentrations of EtBr for the times indicated in figures and legends. Inhibitors of the respiratory chain or translation were added to fresh medium (concentration indicated in figures and legends) 1 h before treatment with EtBr. CCCP treatment was also performed in the reverse order, following 1 h of pre-incubation of cells with 5 μg/ml EtBr. For siRNA depletion experiments, cells were seeded on 10 cm plates and transfected with 100 nM siRNAs and Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) under manufacturer's recommended conditions. Two days after transfection (or on day 3, see legends), cells were seeded at equal densities on 6 cm plates and EtBr was added one day later.

Verification of siRNA-mediated knockdown by Western blotting

The efficiency of mRNA depletion by siRNA-based RNA interference (see Supplementary Table S1 for siRNA sequences) was analyzed at the protein level by Western blotting. Cells were lysed in PBS containing 1% N-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (or 1% SDS where indicated), 1 mM PMSF and Pierce protease inhibitor (Thermo Scientific), incubated on ice for 30 min and centrifuged for 20 min at 20 000 gmax (40). Protein concentrations were determined by the DC protein assay (BioRad), fractionated on 10% SDS-PAGE (30 μg protein per lane) and electroblotted to Whatman® Protran® nitrocellulose membrane (Perkin Elmer). Membranes were blocked in 5% non-fat dried milk/0.1% Tween/TBS followed by incubation with primary and HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies at the dilutions indicated above. Signals were analyzed using the ChemiDoc imaging system (BioRad).

Cell growth and viability

Cultures of 106 cells were seeded in 10 cm cell plates. After 24 h, 2.5 μg/ml of EtBr was added and cells were grown for a further 24 h, then harvested and counted using EVE™ automated cell counter (NanoEnTek), with cell viability determined by trypan-blue exclusion.

Respirometry

Plates of 3 × 106 cells were treated for 24 h with 2.5 μg/ml EtBr. Intact cell respiration in fresh, EtBr-free medium at 37°C, and in permeabilized cells supplied with cI- cIII- or cIV-linked substrate mixtures, was determined using a Hansatech oxygraph as described previously (41), with all reagents sourced from Sigma-Aldrich. To assess coupling of respiration, permeabilized cells supplied with the cI-linked substrate mixture were treated successively with ADP, followed by oligomycin at concentrations ranging from 25 to 75 nM, and FCCP at concentrations ranging from 0.5 to 2 μM, in both cases selecting for further analysis the respective concentration leading to maximal inhibition or activation of oxygen consumption.

mtDNA copy number analysis

Quantification of total mtDNA was performed essentially as described (42), by comparing the efficiencies of amplification of mitochondrial ND1 or ND4 (43) with the nuclear multi-copy gene encoding 18S rRNA (44,45). DNA was extracted with QIAmp DNA mini kit (QIAgen) from cultured cells according to manufacturer's instructions. 10 ng of DNA was used per qPCR reaction, using primers (300 nM) and fluorogenic probes (50 nM), both from Metabion International, as listed in Supplementary Table S1, and TaqMan® Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). Each reaction was performed in triplicate and in two independent runs, using the following profile: one cycle at 95°C for 20 s and then 40 cycles at 95°C for 3 s and 60°C for 30 s. Threshold cycle numbers (Ct) were calculated with StepOnePlus v3.1 program (Applied Biosystems) and the results from the two runs were averaged. The ND4/18S and ND1/18S ratios were calculated from cycle threshold values, and normalized to the values from untreated cells.

Measurement of whole-cell ROS levels by DCF fluorescence

Cells were seeded in 12-well plates at 105 cells per well (1 ml). After 24 h, 2.5 μg/ml EtBr was added and medium diluted to 1.5 ml. After a further 24 h, cells were washed, then stained in 0.5 ml of 2 μM CM-H2DCF-DA (ThermoFisher Scientific) in PBS for 60 min at 37°C in the dark. After washing with 1 ml warmed PBS, cells were detached in 80 μl trypsin–EDTA solution (0.25%, Sigma-Aldrich), for 3 min at 37°C, after which 0.5 ml of fresh medium was added and cells, maintained in the dark throughout, were analyzed with an Accuri® C6 flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) using 488 laser excitation, fast flow and limits set at 30 000 live cells (ROI selection based on forward & side scatter) or 2 min. Corrections for channel crosstalk were estimated from single dye measurements: DCF signal = FL1(533/30) – 2.8% of FL3; EtBr signal = FL3(670/LP) – 1.1% of FL1.

Analysis of mitochondrial translation products

Mitochondrial translation products were pulse-labeled with 35S-methionine in the presence of emetine, and analyzed as described previously (34) by SDS-14% PAGE.

Library preparation for targeted next-generation sequencing

Illumina TruSeq truncated reverse primer 5′ Phos-NNAGATCGGAAGAGCACACGTCTGAACTCCAGTCAC-Amino 3′ was first adenylated using a 5′ DNA Adenylation Kit (New England Biolabs). The adenylated oligo (5 pmol) was ligated to total RNA (500 ng) using truncated T4 RNA Ligase 2 (200 U, New England Biolabs) in a 10 μl reaction. cDNA was generated using a primer complementary to the ligated reverse primer, with Superscipt II RNA reverse transcriptase (400 U, ThermoFisher Scientific) in a 22 μl reaction. Primers were designed for human mitochondrial tRNAs (GenBank entry NC_012920) and the truncated Illumina TruSeq forward adapter sequence 5′ ACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCT 3′ was added to the 5′ end of each of the specific primers (see Supplementary Table S1). Amplification of the selected cDNAs was performed using a 2-step PCR approach. In the first step the designed specific primers with overhangs and Illumina Index primers, 10 pmol each, were used for amplification, with 5 μl of cDNA as template, using Phusion HotStart II DNA Polymerase (ThermoFisher Scientific) with an activation step of 98°C for 10 s and 18 cycles of 98°C for 10 s, 55°C for 30 s and 72°C for 10 s. The obtained PCR products were then treated with Exonuclease I and FastaAP Phosphatase (both from ThermoFisher Scientific) to remove unused primers and nucleotides. An aliquot of the first PCR (5 μl) was used as template for the second PCR in order to incorporate the full-length Illumina adapters for the final library, using the same PCR cycle as above. The obtained products were pooled and purified using AMPure XP (Beckman Coulter). Size selection was done using BluePippin (Sage Sciences) with a cut-off of 220–550 bp. The final pool was checked on Fragment Analyzer (Advanced Analytical) and concentrations were measured using Qubit (Life Technologies).

DNA sequence analysis

The Illumina MiSeq System was used to sequence samples in paired end (R1 and R2) manner. Obtained reads of 326 bp (R1) and 286 bp (R2) were trimmed using cutadapt (v1.7.1; 46) with default parameters, except that minimum read length (m) was set to 50 bp and the quality minimum (q) to 20. In addition, Illumina's Truseq adapter sequences were removed. Reads were trimmed in paired-end manner to keep both read pairs following the criteria defined above. Trimmed paired-end reads were overlapped using FLASH (fast length adjustment of short reads) tool (47). The BLASTN tool (48) was used to divide sequences into different tRNA sequence pools. Within each tRNA sequence pool, sequences were sorted and unique sequences were counted, applying exclusion criteria as indicated in Tables.

Image processing

Blot images were optimized for brightness and contrast and cropped, rotated and/or framed for clarity, but no other manipulations were applied.

RESULTS

High doses of EtBr induce polyadenylation of human mitochondrial tRNAs

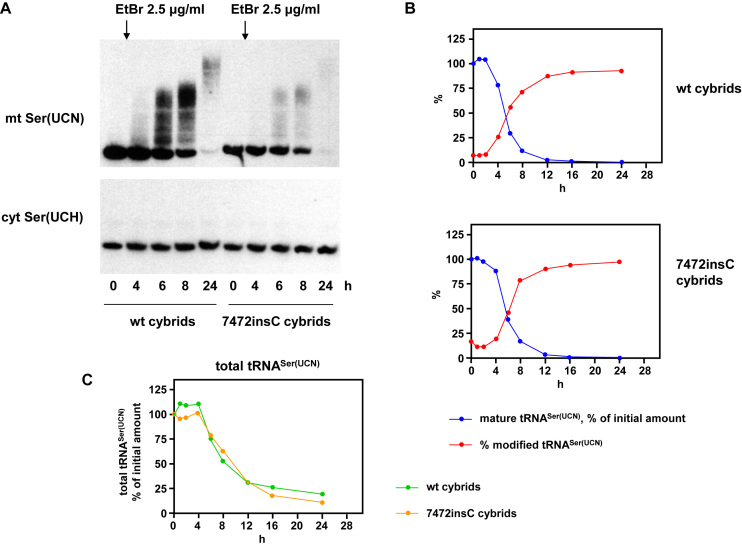

Treatment with 0.25 μg/ml EtBr is sufficient to inhibit mitochondrial RNA synthesis in 143B osteosarcoma cell cybrids, as we showed previously (31). In preliminary experiments, we observed that treatment of cells with a 10-fold higher dose of the drug resulted in altered mobility of mitochondrial tRNAs on denaturing polyacrylamide gels. We investigated this phenomenon in the same 143B cybrids as in our earlier study, which were homoplasmic, respectively, for wild-type mtDNA and for 7472insC mutant mtDNA (33). Exposure of cells to a concentration of 2.5 μg/ml EtBr for 8 h or more resulted in a shift of most of the pool of tRNASer(UCN) to species of higher apparent molecular weight (Figure 1A). The process had already started after 4 h of treatment. By 24 h hardly any of the original tRNA band remained on Northern blots, but much of the modified species had also been degraded (Figure 1A–C). The process had similar kinetics in wild-type and mutant cybrids (Figure 1B, C, Supplementary Figure S1A), despite the lower steady-state abundance of the mutant tRNA ((31), Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Mitochondrial tRNASer(UCN) is modified in cells exposed to high levels of EtBr. (A) Northern blots probed for mitochondrial tRNASer(UCN) and cytosolic tRNASer(UCH) from wild-type and 7472insC mutant 143B cybrid cells treated with 2.5 μg/ml EtBr for the indicated times. For similar blots, where the positions of size markers were determined, see Supplementary Figure S2F. (B, C) Quantitation by phosphorimaging of Northern blots probed for mitochondrial tRNASer(UCN) during 24 h of EtBr treatment. Data were first adjusted for background, then normalized against 5S rRNA, and finally against the corresponding signals at t = 0: (B) levels of mature tRNASer(UCN) and proportion of signal corresponding to modified tRNA migrating at higher apparent molecular weight. For data from a second, independent experiment, as well as data averaged from the two experiments, see Supplementary Figure S1A. (C) Levels of total tRNASer(UCN), in this case averages for the two experiments, showing very similar profiles for wild-type and mutant cybrid cells.

In contrast, cytosolic tRNASer(UCH) was unaffected by EtBr treatment (Figure 1A). The electrophoretic mobility of a typical mitochondrial mRNA, such as for ND3, was also unmodified, but it was progressively degraded (Supplementary Figure S1B), as expected given the known effects of EtBr on mitochondrial transcription and the relatively short half-lives of mitochondrial mRNAs.

The effects of such high levels of EtBr on mitochondrial functions and cell physiology have not previously been tested. We therefore confirmed that treatment with 2.5 μg/ml EtBr over 24 h did not impair cell viability (Supplementary Figure S1C), although cell proliferation was curtailed (Supplementary Figure S1C). Under these conditions, the copy number of mtDNA (Supplementary Figure S1D) and the rate of respiration of both intact and permeabilized cells (Supplementary Figure S1E) declined by ∼50%. Although measurements of membrane potential and mitochondrial ROS production by standard fluorimetric methods were not possible, due to the interference of EtBr fluorescence with that of TMRM or MitoSox, we were able to assess these parameters indirectly. The respiration of permeabilized EtBr-treated cells was stimulated by ADP or by the uncoupler FCCP, and the proportionate inhibition by oligomycin was the same as in control cells (Supplementary Figure S1F), indicating that the treatment did not result in uncoupling or major changes in membrane potential. Estimates of whole-cell ROS based on DCF fluorescence, which were not subject to interference from EtBr (Supplementary Figure S1G), indicated that EtBr treatment did result in substantially increased ROS (Supplementary Figure S1G). Finally, in accord with its hypothesized effects on RNA, EtBr treatment abrogated mitochondrial protein synthesis even more effectively than doxycycline (Supplementary Figure S1H).

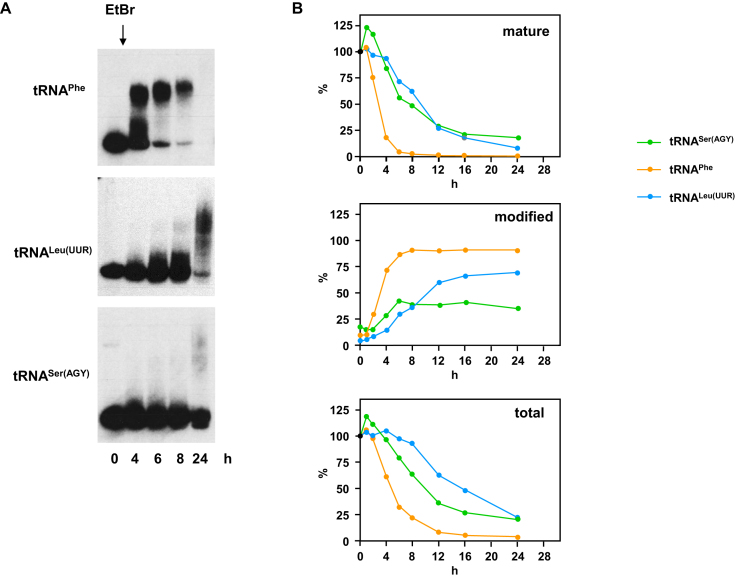

Next, we tested other mitochondrial tRNAs (Figure 2, Supplementary Figure S2A–E). These appeared to vary in their susceptibility to EtBr-induced modification and turnover, and the kinetics thereof. Of those tested, tRNAPhe was the most sensitive to EtBr treatment, with the mature tRNA having almost disappeared after 8 h (Figure 2B, Supplementary Figure S2A), but most of it already modified by 4 h of treatment. At the other end of the spectrum was tRNASer(AGY), approximately 10% of which remained as the mature tRNA even after 24 h, and where the relative amount of the modified tRNA never reached 50% or above.

Figure 2.

Mitochondrial tRNAs are differentially modified in cells exposed to high levels of EtBr. (A) Northern blots probed for the indicated mitochondrial tRNAs in wild-type 143B cybrid cells treated with EtBr for the indicated times (tRNAPhe – 2.5 μg/ml EtBr, tRNALeu(UUR) and tRNASer(AGY) – 3.5 μg/ml EtBr. (B) Quantitation by phosphorimaging of Northern blots probed for the indicated mitochondrial tRNAs in wild-type 143B cybrid cells treated with 2.5 μg/ml EtBr for the indicated times. Data for mature and modified tRNAs were first adjusted for background, then normalized against 5S rRNA, and finally against the corresponding signals at t = 0. In each case the amounts of mature tRNA, the proportion of modified tRNA and the total amount are shown. For data from a second, independent experiment, see Supplementary Figure S2A.

Of the other mitochondrial tRNAs tested, each appeared to respond to treatment with high levels of EtBr with specific characteristics. tRNAGln showed a similar susceptibility to EtBr-induced modification as tRNASer(UCN), while tRNAHis behaved like tRNASer(AGY), and tRNALys and tRNATrp were intermediate (Supplementary Figure S2B). Mature tRNALeu(UUR) turned over slowly like tRNASer(AGY) but a larger fraction became modified (Figure 2B, Supplementary Figure S2A).

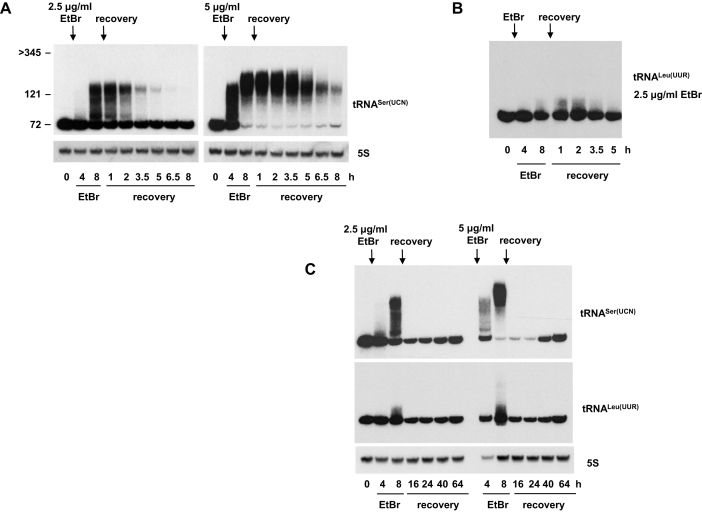

The set represents both clustered and individual tRNAs, tRNAs encoded on each strand of mtDNA, frequent pathological targets, and both the most ‘canonical’ and the most structurally aberrant human mitochondrial tRNAs (tRNALeu(UUR) and tRNASer(AGY), respectively). None of these features correlated in a straightforward manner with susceptibility to EtBr. The extent of modification was EtBr dose-dependent, with 5 or 10 μg/ml EtBr giving a more pronounced response than 2.5 μg/ml (e.g. Figure 3A, C, Supplementary Figure S2D). Apart from tRNASer(UCN), which differed only in abundance, other tRNAs behaved similarly in wild-type and 7472insC mutant cybrids (Supplementary Figure S2C). A similar response was observed in A549 lung carcinoma cells, following treatment with 5 μg/ml EtBr (Supplementary Figure S2E).

Figure 3.

Polyadenylated mitochondrial tRNAs are rapidly degraded after EtBr removal. Northern blots probed for mitochondrial tRNASer(UCN) or tRNALeu(UUR) as indicated, in wild-type 143B cybrid cells treated with 2.5 or 5 μg/ml EtBr for the indicated times, then allowed to recover in the absence of the drug as shown. Where shown, 5S rRNA was used as a loading control. RNA sizes (in nt) were extrapolated from the migration of mature tRNASer(UCN) (72 nt), 5S rRNA (121 nt) and ND3 mRNA (>345 nt). See also Supplementary Figure S3A.

To identify the nature of the novel tRNA products in EtBr-treated cells, total RNA from wild-type cybrid cells was isolated, tRNAs were deacylated, and sequences analyzed initially by Sanger sequencing of cloned, circularized RNAs amplified with tRNA-specific oligonucleotides. For each of tRNASer(UCN) and tRNALeu(UUR) we obtained sequences from >20 clones of 3′-tailed molecules. The extensions consisted almost exclusively of poly(A), with tails of up to 61 nt for tRNASer(UCN) and up to 38 nt for tRNALeu(UUR), some of which were truncated at or within the 3′-terminal CCA. Polyadenylated tRNAs were detected only in EtBr-treated cells: for comparable analyses from untreated control cells see (39).

To obtain a more reliable estimate of the composition of the tails, we employed targeted next-generation sequencing (tNGS) for these and several other mitochondrial tRNAs (Table 1), generating thousands of independent sequence reads (Supplementary Table S2). Non-A residues comprised less than 1% of the total for each of the analyzed tRNAs, but with some variability between them, with tRNASer(UCN) showing the lowest proportion amongst those analyzed, as well as the lowest proportion of truncation at or within the CCA. tNGS revealed 3′ tails of up to 51 nt (Table 1, Supplementary Table S2), although this is likely an underestimate, due to the inherent bias of the method towards shorter tailed molecules. Circularization and cloning introduce a similar bias.

Table 1. Composition of 3′ tails of mitochondrial tRNAs from cells treated with EtBr.

| tRNA | Total reads of tailed tRNA | % truncated at CCA | Maximum tail length | % non-A |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leu(UUR) | 5883, 12073 | 63, 63 | 31, 41 | 0.66, 0.61 |

| Ser(UCN) | 1085, 605 | 6, 0 | 35, 32 | 0.30, 0.21 |

| Leu(CUN) | 4451 | 88 | 44 | 0.98 |

| Ser(AGY) | 12703, 16202 | 57, 47 | 48, 51 | 0.97, 0.78 |

| Lys | 250, 11398 | 84, 77 | 29, 41 | 0.60, 0.38 |

Notes:

1. Based on tNGS of RNA from 143B wild-type cybrid cells, treated with 5 μg/ml EtBr for 8 h.

2. Excluding sequences truncated internally beyond CCA (which have been shown previously to contain adenylate tails even in control cells), as well as unprocessed or partially processed transcripts, dimers or other obvious priming artefacts, e.g. containing internal or terminal primer-derived sequences. Allowing single erroneous base-calls from within the body of each tRNA, reflecting the limited accuracy of NGS.

3. Where shown, the two numbers separated by a comma represent analyses of two different cDNA samples. The first counted all tails of 10 nt or more (for primary sequence data see Supplementary Table S2, sheet 1). The second sampling produced a much greater total read number, so in this case only molecules with tails of ≥ 20 nt were analyzed (primary sequence data in Supplementary Table S2, sheet 2).

Based on the electrophoretic mobility of RNA size markers, tailed tRNASer(UCN) species ranged in apparent strand-length from the size of the mature tRNA up to approximately 150 nt, after 6 h of treatment with 2.5 μg/ml EtBr. Their size increased further by 11 h of such treatment (Supplementary Figure S2F). Although the markers do not permit an accurate extrapolation of the sizes of molecules with unstructured tails, these observations suggest poly(A) lengths of ≥100 nt.

Polyadenylated mitochondrial tRNAs are rapidly turned over

To investigate the fate of the polyadenylated tRNAs, cells were incubated in fresh medium for various times, following EtBr exposure, and sampled periodically for Northern blotting. After the removal of the drug, and following a short, EtBr-dose-dependent delay of a few hours, polyadenylated tRNAs were rapidly degraded, with a half-life of ∼1–1.5 h (Figure 3A, B). Note that in this, and all subsequent experiments, tRNASer(UCN) was used as an example of an extensively polyadenylated tRNA, and, where appropriate, tRNALeu(UUR) as an example of a less extensively polyadenylated tRNA. Although some of the polyadenylated tRNASer(UCN) species may have been trimmed and repaired, their disappearance was not accompanied by rapid restoration of the level of mature tRNA (e.g. see Figure 3A), implying that most of the material was degraded. New transcription is probably sufficient to account for the gradual recovery in the level of mature tRNA seen from 16 h following EtBr removal. Detectable amounts of ND3 mRNA, for example, which is replenished by new transcription, started to reappear after approximately the same recovery time (Supplementary Figure S3B).

For tRNALeu(UUR), which was less affected by EtBr, the polyadenylated species were also turned over rapidly once the drug was removed, with the mature tRNA being restored to its starting level only after 64 h of recovery (Figure 3C, Supplementary Figure S3A). The slow rate of recovery implies that few, if any, of the polyadenylated tRNAs were repaired, once EtBr was removed.

Enzymes required for mitochondrial tRNA polyadenylation and turnover

Our observations concerning the polyadenylation of mitochondrial tRNAs following exposure to EtBr, and their rapid turnover upon removal of the drug, are unprecedented. Many questions are raised regarding the molecular machinery that signals and executes these processes, and their physiological significance. mtPAP is the only RNA polymerase inside human mitochondria that has been previously characterized as being capable of synthesizing non-templated poly(A) tails (on mitochondrial mRNAs, (14)). The enzyme is also responsible for the addition of the discriminator A during maturation of human mitochondrial tRNATyr (12), and is involved in the maturation of mitochondrial tRNACys in Drosophila (11). The low proportion of non-A residues (≤1%, Table 1) in the EtBr-induced tRNA poly(A) tails, similar to that seen in the 3′ tails of mitochondrial mRNAs (14), also suggests that mtPAP is involved, rather than a less faithful enzyme such as PNPase, which has been implicated in polyadenylation in chloroplasts (49–51).

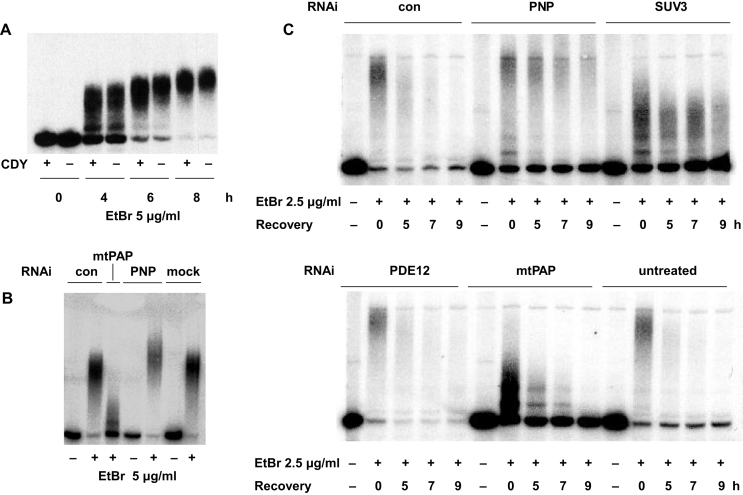

Unusually, mtPAP exhibits relative insensitivity to the chain terminator cordycepin (3′ deoxyadenosine), enabling its activity to be discriminated from other cellular RNA polymerases (52). We therefore tested the cordycepin sensitivity of mitochondrial tRNA polyadenylation produced by EtBr treatment. At 20 μg/ml, cordycepin had no effect on the polyadenylation of tRNASer(UCN) over 8 h of EtBr exposure (Figure 4A), despite the fact that 20 μg/ml cordycepin had a profound effect on the steady-state level of ND3 mRNA (Supplementary Figure S4A), synthesis of which depends on the cordycepin-sensitive mitochondrial RNA polymerase responsible for global transcription (53,54). In contrast, cordycepin treatment for 8 h had little effect on the steady-state level of tRNASer(UCN) in the absence of EtBr (Supplementary Figure S4A).

Figure 4.

Enzymes required for mitochondrial tRNA polyadenylation and turnover. Northern blots probed for mitochondrial tRNASer(UCN), following EtBr treatment in 143B wild-type cybrid cells also treated with cordycepin (CDY) or siRNAs against different genes as indicated. (A) Cells pre-treated for 1 h and then continuously throughout the experiment with or without 20 μg/ml cordycepin, as shown. (B) Cells pre-treated for 96 h with siRNAs as indicated (see Supplementary Table S1), or mock-transfected, before 6 h of treatment with or without EtBr, as shown. (C) Cells pre-treated for 72 h with siRNAs as indicated (see Supplementary Table S1), or untreated, before 6 h of treatment with or without EtBr, followed by recovery for the indicated times after removal of the drug. In each siRNA experiment shown, knockdown at the protein level was verified by western blots, representative examples of which are shown in Supplementary Figure S4B and D. 72 h or 96 h of knockdown gave essentially identical results, both on Western and Northern blots. Signals detected by phosphorimaging in parts (B, C). Note that we confirmed the effects of knockdown of mtPAP, SUV3 and PNPase using alternative siRNAs (Supplementary Figure S4E, F, G).

To test further whether mitochondrial tRNA polyadenylation is due to mtPAP or PNPase, we used siRNA-based RNA interference combined with EtBr treatment. After verifying knockdown at the protein level (Supplementary Figure S4B, S4G), we used Northern blots to examine the effects on the length of poly(A) tails added to tRNASer(UCN) (Figure 4B, Supplementary Figure S4C). RNAi directed against mtPAP consistently resulted in drastic shortening of the poly(A) tails, but not in their complete abolition (Figure 4B, Supplementary Figure S4C, E), whereas RNAi directed against PNPase resulted in tail lengthening (Figure 4B, Supplementary Figure S4C), although this was less evident when EtBr was used at a lower dose, with RNAi for less time (Figure 4C, upper panel, Supplementary Figure S4E). When the two genes were knocked down simultaneously, tails were slightly decreased in length compared with untreated cells, or with cells treated with a control siRNA (Supplementary Figure S4C), consistent with the two enzymes acting antagonistically.

We took a similar approach to identify the gene products responsible for turnover of polyadenylated tRNAs following removal of EtBr. mtPAP knockdown had no effect on the turnover of the shortened tRNASer(UCN) tails (Figure 4C, Supplementary Figure S4F), whereas PNPase knockdown delayed and largely prevented the degradation of polyadenylated tRNASer(UCN), (Figure 4C, upper panel, Supplementary Figure S4F), with 3 or 4 days of RNAi almost completely inhibiting the process. PNPase has been previously implicated in general RNA turnover in human mitochondria as a component of the ‘degradosome’ (19). We therefore tested the other identified component of this machinery, the RNA helicase SUV3, again first verifying the effect of knockdown at the protein level (Supplementary Figure S4D, G). SUV3 knockdown resulted in shortened poly(A) tails in the presence of EtBr (Figure 4C, upper panel, Supplementary Figure S4F), but also inhibited their subsequent degradation (Figure 4C, upper panel, Supplementary Figure S4F). To exclude off-target effects, we confirmed these findings in each case, using a second siRNA (Supplementary Table S1, Figure S4E, F).

The 2′ phosphodiesterase encoded by PDE12, previously implicated in the turnover of the poly(A) tails of human mitochondrial mRNA, in tRNA repair (12,55) and in the turnover of specific, oligoadenylated tRNAs (21), was tested similarly. Although PDE12 knockdown was effective at the protein level (Supplementary Figure S4D), this had no effect on the turnover of polyadenylated tRNASer(UCN) (Figure 4C, lower panel). However, PDE12 knockdown had reproducible effects on the EtBr-induced adenylation of two other tRNAs (Supplementary Figure S4H, S4I), that were previously shown to be susceptible to oligoadenylation in its absence (21).

In the case of tRNALys, PDE12 knockdown revealed a more slowly migrating form of the tRNA that was seen even prior to exposure to EtBr (blue arrows in Supplementary Figure S4H), which we assume to correspond with the previously reported oligoadenylated species (21). Following EtBr exposure, while the accumulation of polyadenylated species was very similar to that seen in cells treated with a control siRNA, the mature form of the tRNA was massively depleted after EtBr treatment, implying that PDE12 is somehow required for its stabilization, rather than turnover. The polyadenylated tRNALys species were typically degraded more slowly during recovery than were those derived from tRNASer(UCN), but PDE12 knockdown may actually have accelerated this process. The effects on PNP, mtPAP and SUV3 knockdown on tRNALys adenylation were qualitatively similar to those seen for tRNASer(UCN) (Supplementary Figure S4H).

In the case of tRNAHis, short-tailed molecules were below the detection limit in PDE12 knockdown cells, prior to EtBr exposure. However, they were induced by EtBr, with PDE12 knockdown facilitating the process, such that almost all of the tRNA was converted to a discrete species migrating more slowly than in cells treated with a control siRNA (Supplementary Figure S4I). PDE12 knockdown did not prevent the turnover of these species during recovery from EtBr. Once again, knockdown of PNP, mtPAP and SUV3 produced qualitatively similar effects on EtBr-induced adenylation and turnover of tRNAHis as seen for tRNASer(UCN) (Supplementary Figure S4I). The overall conclusion is that each of the tRNAs tested has a specific behaviour in response to PDE12 knockdown, EtBr treatment and recovery. Furthermore, the processes of tRNA polyadenylation and oligoadenylation, plus the corresponding deadenylation, appear to operate independently.

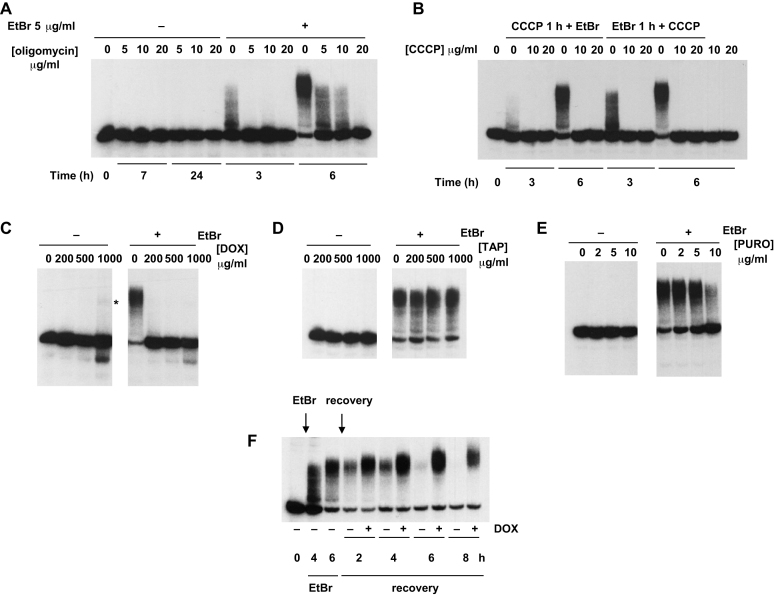

Production and turnover of polyadenylated tRNAs depends on mitochondrial metabolism

Macromolecular synthesis is an energy-requiring process, and the main substrate for polyadenylation is ATP. We confirmed that inhibition of mitochondrial ATP synthesis via treatment either with an inhibitor of ATP synthase (oligomycin, Figure 5A) or an uncoupler (CCCP, Figure 5B, Supplementary Figure S5A) resulted in a complete block of the mitochondrial tRNA polyadenylation seen upon EtBr exposure. CCCP had this effect regardless of whether it was added prior to or following EtBr exposure (Figure 5B, Supplementary Figure S5A).

Figure 5.

Mitochondrial tRNA polyadenylation and turnover are influenced by drugs that inhibit ATP synthesis or protein synthesis. Northern blots probed for mitochondrial tRNASer(UCN), in 143B wild-type cybrid cells treated with or without EtBr for the indicated times: (A) plus the indicated concentrations of oligomycin, with one additional hour of pre-treatment; (B) plus the indicated concentrations of CCCP, with one additional hour of CCCP pre-treatment, or CCCP addition one hour later, as shown. Final two tracks were from cells treated only with CCCP for 6 h. See also Supplementary Figure S5. In other panels cells pre-treated for 1 h with the indicated doses of (C) doxycycline (DOX), (D) thiamphenicol (TAP) or (E) puromycin (PURO), and then for a further 6 h with (+) or without (–) concomitant treatment with 5 μg/ml EtBr, as shown. (F) Treatment with (+) or without (–) 200 μg/ml doxycycline, plus 5 μg/ml EtBr added and withdrawn at times indicated by arrows. Asterisk denotes tRNA modified at the highest dose of doxycycline, in the absence of EtBr.

Next we tested the effect of inhibitors of mitochondrial protein synthesis. Doxycycline prevented mitochondrial tRNA polyadenylation in response to EtBr, at doses between 200 and 1000 μg/ml (Figure 5C, Supplementary Figure S5B). Paradoxically, at the highest doses used, it promoted a tiny accumulation of modified species co-migrating with polyadenylated tRNAs, even in the absence of EtBr (Figure 5C, Supplementary Figure S5B, asterisked species). Thiamphenicol had no effect on mitochondrial tRNASer(UCN) polyadenylation (Figure 5D), while puromycin had a mild inhibitory effect (Figure 5E), but only at the highest dose used (10 μg/ml). Both drugs had an inhibitory effect on tRNALeu(UUR) polyadenylation at somewhat lower doses, i.e. 0.5–1 mg/ml thiamphenicol or 2–5 μg/ml puromycin (Supplementary Figure S5C, D). Doxycycline added during the recovery phase also blocked the turnover of tRNAs that had been polyadenylated in response to EtBr (Figure 5F, Supplementary Figure S5E). This resulted in the accumulation of longer products, both for tRNASer(UCN) (Figure 5F) and tRNALeu(UUR) (Supplementary Figure S5E).

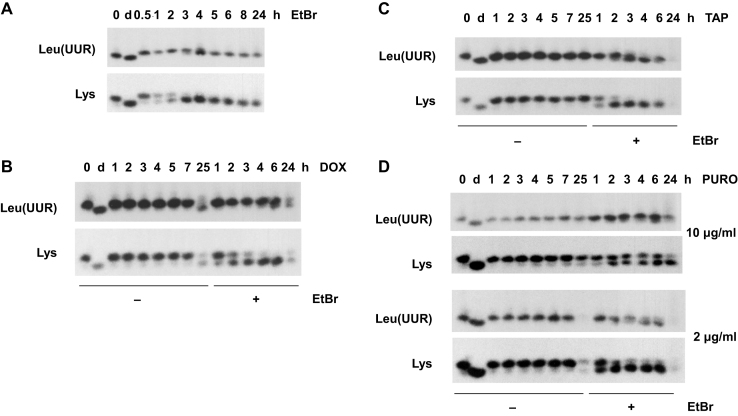

To ascertain whether tRNA polyadenylation under these various conditions was determined only by the extent of tRNA deacylation, we used acidic polyacrylamide gel-blots, probed for tRNAs whose aminoacylation status can be easily visualized by their mobility on such gels, tRNALys and tRNALeu(UUR) (Figure 6). These tRNAs are also less rapidly modified than, for example, tRNAPhe or tRNASer(UCN) (Figures 1 and 2, Supplementary Figures S1A, S2), allowing us to investigate the acylation status of these tRNAs during a time when most of the tRNA remained unmodified.

Figure 6.

Aminoacylation status of mitochondrial tRNAs in drug-treated cells. Northern blots from acidic polyacrylamide gels, probed for mitochondrial tRNAs as denoted by their decoding specificities, in 143B wild-type cybrid cells treated (+) or not (–) with 5 μg/ml EtBr and/or 200 μg/ml doxycycline (DOX), 200 μg/ml thiamphenicol (TAP) or puromycin (PURO) at the indicated doses, for the times shown. In the case of concomitant treatments (+), incubation times with EtBr, as shown, do not include an additional 1 h of pre-treatment with the indicated drug. Deacylated tRNA samples denoted as d.

Both tRNAs were extensively deacylated within 3-4 h of exposure to EtBr (Figure 6A), corresponding roughly with the period when their polyadenylation started to become substantial (see Figure 2A, B, Supplementary Figure S2B). Doxycycline, despite its inhibitory effect on both polyadenylation (Figure 5C, Supplementary Figure S5B), and turnover (Figure 5F, Supplementary Figure S5E), did not abolish deacylation (Figure 6B), merely delaying it. Thiamphenicol at 200 μg/ml, which had no effect on tRNALeu(UUR) polyadenylation (Supplementary Figure S5C), also had no effect on deacylation (Figure 6C). Conversely, puromycin, which decreased the extent of tRNALeu(UUR) polyadenylation (Supplementary Figure S5D), also inhibited or delayed deacylation (Figure 6D), although this was pronounced only at the higher dose of the drug. Overall, we conclude that deacylated mitochondrial tRNAs can be polyadenylated, following their accumulation.

A pathological mutant mitochondrial tRNA is polyadenylated

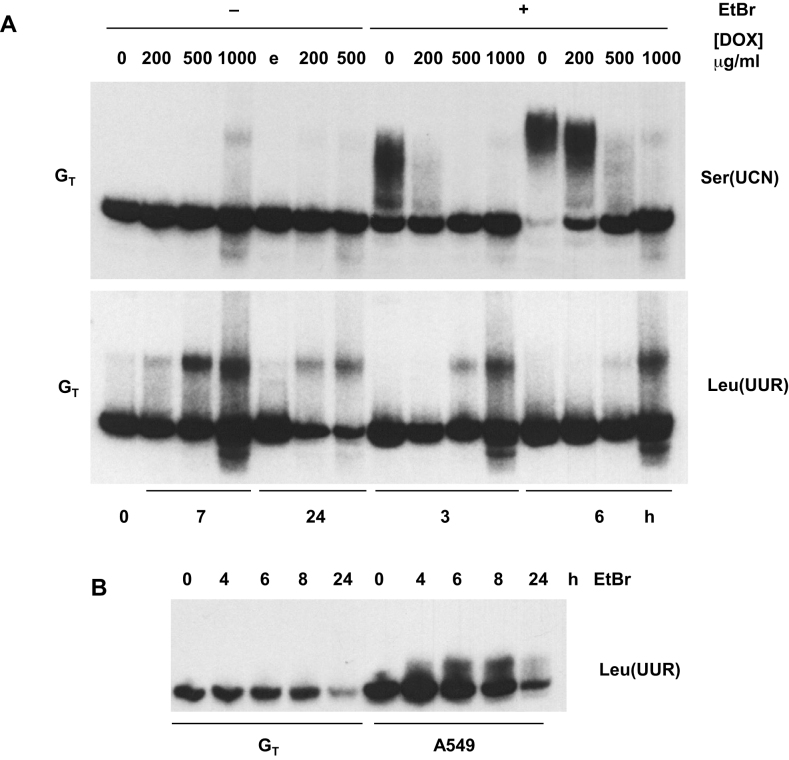

The foregoing data led us to hypothesize that structural distortion of mitochondrial tRNAs by high levels of EtBr induced their exclusion from the pool of translationally competent tRNAs, entraining their polyadenylation and subsequent degradation. If supported, such a mechanism may represent a natural quality-control pathway relevant to pathology. To test this idea, we made use of a cell line effectively homoplasmic for the dysfunctional tRNALeu(UUR) carrying the A3243G MELAS mutation, but in which normal mitochondrial protein synthesis and respiratory function is maintained by the presence of a suppressor tRNA (35,56). The A3243G mutation is known to produce a variety of tRNA abnormalities that effectively cripple its ability to participate in translation, including decreased steady-state level and inefficient aminoacylation (37,57) associated with failure of wobble-base modification (58). The A549 lung-carcinoma-derived cybrid cell line GT, which is almost (≥99%) homoplasmic for the A3243G mutation but heteroplasmic for the G12300A tRNALeu(CUN) suppressor mutation and respiration-competent, was studied under various conditions facilitating the detection of polyadenylated mitochondrial tRNAs in control cells.

As in 143B-derived cells (Figures 1–5), tRNASer(UCN) was polyadenylated in GT cells after treatment with high levels of EtBr (Figure 7A, upper panel), whereas this was blocked by treatment with doxycycline. Prolonged (7 h) treatment of GT cells with a high concentration (1 mg/ml) of doxycycline in the absence of EtBr also revealed a tiny amount of modified tRNASer(UCN), co-migrating with the species polyadenylated after EtBr treatment, essentially the same as seen in 143B cell cybrids (Figure 5C).

Figure 7.

Polyadenylation of mutant tRNALeu(UUR) is induced by doxycycline, not EtBr. Northern blots of mitochondrial tRNAs, denoted by their decoding specificities, in A549 or GT cybrid cells as indicated: (A) cells treated with the indicated doses of doxycycline (DOX) with (+) or without (–) concomitant treatment with 5 μg/ml EtBr, for the times shown (plus 1 h of preincubation with DOX where applicable), or (B) in cells treated for the indicated times with 5 μg/ml EtBr. Control treatment with an equivalent volume of 70% ethanol, the solvent used for delivery of doxycycline, denoted by e. Note that control A549 cells are wild-type for tRNALeu(UUR), whereas GT cells are homoplasmic for the A3243G mutant tRNALeu(UUR). See Figure S6A for longer exposure of the tRNALeu(UUR) blot from GT cells. Note that the steady-state level of tRNALeu(UUR) in GT cells compared with control cells is low, due to the A3243G mutation, as seen in part (B). Thus, a much longer exposure is shown for the tRNALeu(UUR) panel than for the tRNASer(UCN) panel in part (A).

However, tRNALeu(UUR) exhibited a completely different behaviour in GT cells (Figure 7A, lower panel). EtBr treatment alone had only a minor effect on the tRNA (Figure 7B, Supplementary Figure S6A), whereas doxycycline produced a strong, dose-dependent shift in its mobility, suggestive of polyadenylation, that was partially inhibited by concomitant treatment with EtBr (Figure 7A, lower panel). The putatively polyadenylated species of tRNALeu(UUR) was also faintly visible even in untreated cells. As observed in 143B cell cybrids (Figure 6B), the deacylation of tRNALeu(UUR) in control A549 cells that was brought about by EtBr treatment (Supplementary Figure S6B) was delayed by prior exposure to doxycycline (Supplementary Figure S6C), whereas in GT cells, where the (mutant) tRNA was already partially deacylated, EtBr led to complete deacylation within 1 h, irrespective of whether or not the cells were pre-treated with doxycycline (Supplementary Figure S6B, C).

To confirm that the modification of tRNALeu(UUR) prominently revealed by doxycycline treatment in GT cells was once again 3′ polyadenylation, we analyzed the products by Sanger sequencing of the prominent modified band after circularization and cloning, which was once again followed up by tNGS (Table 2, Supplementary Table S3). Tails were again composed primarily of poly(A), with non-A residues at a similar frequency as in the tailed tRNALeu(UUR) species generated in response to EtBr treatment. In this case, however, most of the mutant tRNA retained CCA.

Table 2. Composition of 3′ tails of mitochondrial tRNALeu(UUR) from GT cells treated with doxycycline.

| Total reads of tailed tRNA | % truncated at CCA | Maximum tail length | % non-A |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5988 | 9 | 29 | 0.67 |

Notes:

1. Based on tNGS of RNA from GT cells, treated with 1 mg/ml doxycycline for 24 h (see Figure 7A).

2. Exclusions as for Table 1.

3. For primary sequence data see Supplementary Table S3.

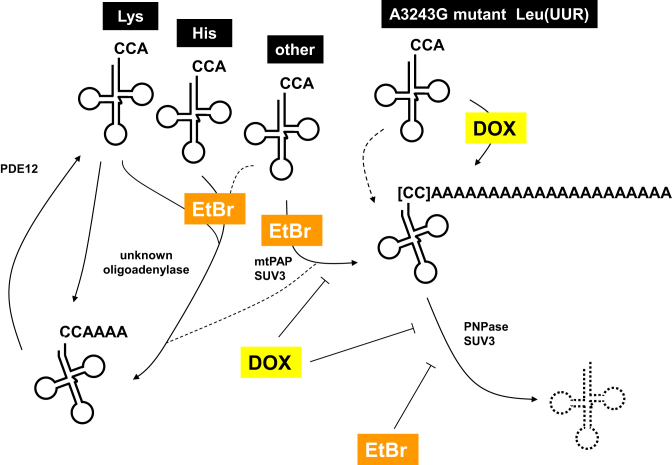

DISCUSSION

In this study, we followed up the unexpected observation that, at high doses, EtBr treatment of cultured human cells resulted in the polyadenylation of mitochondrial tRNAs and their subsequent degradation after removal of the drug. Other cellular RNAs, such as a cytosolic tRNA or a mitochondrial mRNA, were not modified in this way by EtBr. Mitochondrial tRNA polyadenylation was dependent on ATP synthesis and required mtPAP and SUV3, while turnover required PNPase and SUV3, and inhibitor studies suggested the possible involvement of the mitoribosome. A dysfunctional and structurally abnormal tRNA associated with human disease was also subject to polyadenylation, implying that the pathway may operate as a more general quality-control mechanism. Our findings are summarized in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Summary of mitochondrial tRNA-metabolic processes revealed in the study. Schematic diagram summarizing the main results. Mitochondrial tRNAs are denoted by their decoding specificity. CCA denotes normal 3′ termini, CCAAAA denotes oligoadenylated tRNA and CC followed by the longer A run denotes polyadenylated tRNA. Square brackets indicate that some polyadenylated tRNAs are also truncated at CCA, to a degree that is tRNA-specific. Oligoadenylation is also induced by EtBr in some tRNAs (Lys and His indicated as examples, although differing in their susceptibility), and involving an unknown enzyme. PDE12 is required for rapid removal of oligo(A) from these tRNAs, as reported previously (21). EtBr treatment or the A3243G mutation introduce a structural distortion of the relevant tRNA (indicated by a kink in the structure), resulting in deacylation and adenylation. tRNA polyadenylation in response to EtBr treatment requires mtPAP and SUV3, while turnover of polyadenylated tRNAs (dashed cloverleaf) requires PNPase and SUV3. The accumulation of the polyadenylated A3243G mutant tRNA is stimulated by doxycycline (DOX), which inhibits both tRNA polyadenylation and turnover in cells treated with EtBr. Dashed arrows denote minor or uncertain pathways, including low-level polyadenylation of the A3243G mutant tRNALeu(UUR) in cells not treated with doxycycline.

Physiological relevance of tRNA polyadenylation

As discussed in the Introduction, polyadenylation serves diverse purposes in biology. In metazoan mitochondria, mRNA polyadenylation remains enigmatic, with poly(A) apparently serving as a tag for stabilization of some RNAs, but the destabilization of others. Oligoadenylated, mostly truncated mitochondrial tRNA species have been previously reported (7,12), and have been observed to accumulate when PDE12 was knocked down (12,21). While some have been proposed as processing intermediates (12) their overall provenance and abundance remain unexplained.

In the present study, polyadenylation of mitochondrial tRNAs was revealed under the admittedly non-physiological conditions of prolonged treatment of cells with a nucleic acid intercalating agent, EtBr. However, it was also observed in the case of a tRNA carrying a pathological mutation which impairs base-modification and aminoacylation, and disables translational function. In both cases, polyadenylated tRNAs accumulated to substantial levels, but only while their turnover was blocked, respectively by EtBr itself, or by doxycycline. Treatment with a lower concentration of EtBr, sufficient to block mitochondrial transcription, did not result in tRNA polyadenylation (31), but even the higher level of EtBr did not impair cell viability (Supplementary Figure S1C). Since the affinity of EtBr for structured RNA is less than for DNA, our findings are consistent with the idea that tRNA polyadenylation is induced by structural distortions resulting either from EtBr intercalation or from mutation, rendering the tRNA structurally abnormal and impairing its physiological function. The highly variable susceptibility to polyadenylation in the presence of EtBr, exhibited by different mitochondrial tRNAs, most likely reflects the different degree of structural distortion produced by the drug. Whether RNA polyadenylation depends on exact structural features, or is a default pathway for any free 3′ end of a structurally abnormal or misfolded RNA remains to be determined. The latter seems probable, if it is assumed that this operates as a surveillance pathway.

The biogenesis of tRNAs is a complex multi-step process, hence it is logical that any significant failure thereof that impairs translational function would be subject to a quality-control process geared to preventing interference with the fidelity or efficiency of protein synthesis, as previously inferred in bacteria (24). Based on our study, tRNAs appear to be the only class of mitochondrial transcript that are systematically destabilized by polyadenylation, in response to structural aberrations. This pathway may represent the original function for poly(A) in mitochondria, with the addition of stable poly/oligo(A)-tails at the 3′ ends of mRNAs and rRNAs having evolved later, as a distinct process. It may also serve a wider function, for example, to eliminate misprocessed transcripts.

Although RNA-intercalating drugs are not frequently encountered in nature, structural abnormalities in tRNAs will result from many other causes, including pathological mutations, errors in RNA processing or base modification, or the actions of some antibiotic drugs (59). All such processes are potentially influenced by exposure to diverse environmental agents and conditions. Point mutations in tRNA genes are the most common class of pathological lesion in mtDNA after deletions (which themselves affect multiple tRNAs). Many of them have multiple downstream effects on tRNA structure, abundance, acylation and translational function, while another prominent class of disease mutations affects the nuclear genes responsible for these various steps in mitochondrial tRNA metabolism (60). Polymorphisms that do not result in an overt pathology might also give rise to tRNAs that are poorly acylated, modified or processed in, and depend on this pathway for the maintenance of translational fidelity.

RNA surveillance based on polyadenylation may also function as defence against the mitochondrial milieu being invaded or hijacked by a virus (61), or as a response to the hypothetical case of cytosolic RNAs that might have been aberrantly imported into mitochondria, disturbing mitochondrial functions. Programmed import of specific cytosolic tRNAs has been documented in many organisms (62).

Machinery of mitochondrial tRNA polyadenylation and turnover

The relative cordycepin insensitivity of EtBr-induced mitochondrial tRNA polyadenylation (Figure 4A) rules out most cellular RNA polymerases from involvement, including the mitochondrial RNA polymerase and the major polyadenylases of the nucleus and cytosol. Conversely, RNA interference (Figure 4B, C, Supplementary Figure S4C, E) clearly implicates mtPAP (PAPD1), which was already suggested by the low incorporation of non-A residues into tRNA 3′ tails (Tables 1 and 2), similar to that seen in mitochondrial mRNAs (14). A low rate of incorporation of non-A residues is consistent with the fact that mtPAP is able to use all four ribonucleoside triphosphates in vitro (63) and, furthermore, has been implicated in the oligouridylation of histone mRNAs in the cytoplasm (17), although this has been questioned (18,64). Incorrectly processed transcripts have also been reported to be uridylated in mitochondria (65,66). mtPAP knockdown did not completely abolish the modification of mitochondrial tRNAs upon EtBr treatment. It consistently resulted in the appearance of tRNA species extended by only a short distance (Figure 4B, C, Supplementary Figure S4E), compared with the longer tails seen when mtPAP was still present at wild-type levels. Although we cannot exclude that this reflects a small amount of residual mtPAP activity, it may also indicate the action of another, unidentified oligoadenylase, as suggested also in the case of mitochondrial mRNAs (15,67). There are no obvious candidates for such an enzyme, but one possibility may be the 3′ nucleotidyl transferase (TRNT1) that creates the CCA terminus of both cytosolic and mitochondrial tRNAs. This enzyme is part of a superfamily (68) that also includes the poly(A) polymerases (69). However, testing its involvement in tRNA adenylation is not straightforward, because of its pleiotropic functions in tRNA metabolism.

EtBr-induced tRNA polyadenylation appears also to depend on the SUV3 helicase, since its knockdown resulted in the shortening of tRNA poly(A) tails (Figure 4C, Supplementary Figure S4F). SUV3 in different taxa has already been shown to play diverse roles in mitochondrial RNA metabolism. The SUV3 orthologue in Schizosaccharomyces pombe has been implicated in mRNA processing (70). In Drosophila it functions in the processing of mitochondrial tRNAs and in poly(A) tail-lengthening of 16S rRNA and of some mitochondrial mRNAs (71). Furthermore, SUV3 has previously been reported to facilitate the polymerase function of human mtPAP, under specific conditions, involving a direct interaction between the proteins (72). We surmise that the highly structured nature of tRNAs leads to transient interactions of nascent poly(A) tails with the body of the tRNA, impeding the processivity of mtPAP, and that SUV3 can relieve this constraint. This may apply, for example, in the case of tRNASer(UCN), which has a pyrimidine- (and specifically U-) rich region near to its 3′ end, although this structure may also contribute to the rather efficient and stable polyadenylation of the tRNA.

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Suv3 is a component of the mitochondrial ‘degradosome’, the enzyme complex responsible for RNA turnover (73). Human SUV3 (SUPV3L1) has been inferred to function similarly (74), but in combination with a different nuclease, PNPase instead of Dss1 (19,72), despite the fact that most PNPase is located in the inter-membrane space (75). In our analysis, SUV3 knockdown also blocked the turnover of polyadenylated mitochondrial tRNA. Thus, SUV3 appears to be required both for full polyadenylation and for turnover.

Knockdown of PNPase resulted in tRNA poly(A) tail lengthening (Figure 4B, Supplementary Figure S4C, E) as well as inhibition of turnover (Figure 4C, Supplementary Figure S4F). PNPase is considered to operate reversibly, i.e. it can function, effectively, either as an RNA polymerase or as a nuclease, although catalyzing a different chemistry than conventional enzymes of either class. Its role in creating poly(A) tails in chloroplasts has already been mentioned, but in human mitochondria its role is generally antagonistic to mtPAP (8,15,72,76,77), and this appears to be the case here also for tRNA polyadenylation, with mtPAP required for tail lengthening but PNPase performing the opposite role, as well as being required for the (delayed) degradation of the polyadenylated tRNAs, following removal of EtBr. The PDE12-mediated removal of oligo(A) tails from a subset of tRNAs (including tRNAHis and tRNALys; 21) appears to be a largely independent process, in the sense that PNPase knockdown did not affect the turnover of oligoadenylated tRNAs, while PDE12 knockdown did not block the degradation of those bearing longer poly(A) tails (Supplementary Figure S4H, I). However, EtBr treatment induced both the oligoadenylation and polyadenylation of these tRNAs. Interestingly, different tRNAs also varied in their susceptibility to truncation at CCA prior to polyadenylation, with tRNASer(UCN) and the A32343G mutant tRNALeu(UUR) both showing a very low amount of truncation compared with other tRNAs (Tables 1 and 2).

Although polyadenylation of structurally abnormal tRNAs might be considered a tag for their destruction, it is perhaps more parsimonious to regard polyadenylation by mtPAP as a default pathway for misfolded RNAs, which also entrains their PNPase/SUV3-mediated degradation by virtue of the unstructured nature of the poly(A) tail. If assumed to be an ancient process, it is curious that poly(A)-mediated RNA turnover is absent from S. cerevisiae mitochondria, which lack orthologues for both mtPAP and PNPase. Thus, if there is an analogous pathway in yeast mitochondria for removal of structurally abnormal tRNAs, it must involve other enzymes, for which the nuclease Dss1 (73) is one obvious candidate.

Possible involvement of the translational machinery in tRNA polyadenylation

The varying effects of different inhibitors of mitochondrial protein synthesis on these processes suggest a possible but not straightforward association with the translational machinery. Doxycycline strongly inhibited EtBr-induced tRNA polyadenylation and the subsequent turnover of polyadenylated tRNAs, whereas thiamphenicol and puromycin had only minor effects. In contrast, doxycycline enhanced the polyadenylation of the A3243G-mutant tRNALeu(UUR) (Figure 7A), which occurred in the absence of EtBr, despite the fact that the mutant tRNA probably participates only minimally in protein synthesis.

By analogy with data on bacterial ribosomes, doxycycline blocks aminoacyl-tRNA access to the ribosome A-site, by binding to a region which overlaps the binding pocket for the tRNA anticodon stem-loop (78,79). This prevents the first step in the elongation cycle ((80); see (81,82) for review). However, thiamphenicol, like its less potent analogue chloramphenicol, inhibits the peptidyl transferase step of elongation (83), although this depends on the specific terminal amino acids in the nascent peptide chain and the A-site (84). Puromycin acts as a chain terminator (85) of both cytosolic and mitochondrial translation. The different effects of these drugs suggests that tRNA polyadenylation and turnover might be brought about by a machinery associated with the mitoribosome A-site, or modulated by a signal originating there and reflecting the manner of its occupancy. However, EtBr itself abrogated mitochondrial protein synthesis (Supplementary Figure S1H), while doxycycline did not induce a significant accumulation of polyadenylated tRNAs except at very high levels, or of a structurally abnormal tRNA that was already present. The effects of doxycycline could therefore be secondary, or even independent of the translation machinery.

The components of the human mitochondrial ‘degradosome’, SUV3 and PNPase (19), have been reported to co-localize in discrete foci that contain other components of the machinery of mitochondrial RNA processing, including mtPAP (86), as well as being the sites of mitoribosome biogenesis (87). A sub-population of these foci is intimately associated with mtDNA nucleoids (86,88). However, translation initiation and elongation factors have not been reported as components of these granules (86), implying that they are not sites of ongoing protein synthesis, although affinity purification of the mitochondrial ribosome recycling factor mtRRF did result in the co-isolation of nucleoid, RNA processing and translation proteins (89). Cross-linking studies have also revealed such associations (90). Some other RNA quality control pathways, such as nonsense-mediated decay or no-go decay, are clearly ribosome-dependent (91). Furthermore, Temperley et al. (92) found that deadenylation of an abnormal ATP8/ATP6 mRNA, produced as a result of a mutation at the gene boundary with MTCO3, was dependent on ongoing translation, although they did not determine whether the degradation machinery was directly associated with the mitoribosome. In sum, the involvement of the mitoribosome in polyadenylation and turnover of abnormal tRNAs is unproven. The presence of an invalid tRNA in the mitoribosome A-site may be involved in triggering the response, but tRNA surveillance may also operate independently of the translation apparatus.

Significance for mitochondrial tRNA pathologies

The existence of a surveillance system to detect and dispose of abnormally structured RNAs, including the pathological mutant tRNALeu(UUR) bearing the A3243G mutation, suggests the importance of this pathway in human pathology. The molecular, cellular and physiological effects of pathological mutations affecting mitochondrial tRNAs are highly diverse, and exhibit a great variety of tissue specificities that remain largely unexplained. Mostly, they are marked by decreased steady-state abundances of the affected tRNA. Failure of a surveillance mechanism for removing structurally abnormal tRNAs could result in their participating in protein synthesis, triggering harmful downstream effects. This might explain some puzzling observations: for example, the case of a carrier mother homoplasmic for a pathological mutation in mitochondrial tRNAVal that is present in her cells at very low levels without drastic clinical effects, yet is robustly associated with fetal/infantile lethality in her children (93,94). The high heteroplasmic threshold levels for pathological tRNA mutations also makes sense if aberrant tRNAs are disposed of before they can cause active damage. Finally, the broad failure of negative selection against tRNA mutations in the female germline (95) could be accounted for by a stringent surveillance mechanism that maintains aberrant tRNAs only at very low levels.

The polyadenylation and turnover of abnormal tRNAs may be potentiated by more general stress responses. The possible involvement of the mitoribosome has already been discussed, but other physiological triggers elicited by high levels of EtBr (Supplementary Figure S1C–G) may be involved, including increased ROS, respiratory defects and mtDNA copy number depletion. Activating a surveillance pathway targeting abnormal RNAs in affected tissues may be one fruitful approach to combating mitochondrial tRNA pathologies.

The precise structural distortions that trigger polyadenylation of deacylated tRNAs and their subsequent degradation are not obvious, and may depend on further, thus far unidentified factors. The response of the mitoribosome to very low levels of a given tRNA has not been studied extensively, but prolonged stalling is assumed to trigger premature termination and ribosome recycling. Four members of the (class 1) ribosomal release factor family have been identified in mitochondria (96), three of which have been proposed to be involved in rescuing stalled mitoribosomes (97–99). One or more of them could be involved in the response to tRNA insufficiency. Limiting their action in the event of high levels of heteroplasmy for a pathological tRNA mutation could be one way to break a futile cycle of mitoribosome initiation and premature termination, enabling the productive synthesis of mitochondrially encoded polypeptides to proceed.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Eeva-Marja Turkki for library preparation and sequencing, Laurence Bindoff, Bob Lightowlers, Brendan Battersby and Uwe Richter for advice and useful discussions, Maarit Partanen for technical assistance and Troy Faithfull for critical reading and editing of the manuscript.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

Academy of Finland [Centre of Excellence grant 272376; Academy Professorship grant 283157 to H.T.J.]; University of Tampere; Tampere University Hospital Medical Research Fund; Sigrid Juselius Foundation. Funding for open access charge: University of Tampere.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Edmonds M. A history of poly A sequences: from formation to factors to function. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 2002; 71:285–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dreyfus M., Regnier P.. The poly(A) tail of mRNAs: bodyguard in eukaryotes, scavenger in bacteria. Cell. 2002; 111:611–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rorbach J., Bobrowicz A., Pearce S., Minczuk M.. Polyadenylation in bacteria and organelles. Methods Mol. Biol. 2014; 1125:211–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nagaike T., Suzuki T., Ueda T.. Polyadenylation in mammalian mitochondria: insights from recent studies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008; 1779:266–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schuster G., Stern D.. RNA polyadenylation and decay in mitochondria and chloroplasts. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2009; 85:393–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lange H., Sement F.M., Canaday J., Gagliardi D.. Polyadenylation-assisted RNA degradation processes in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2009; 14:497–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Slomovic S., Laufer D., Geiger D., Schuster G.. Polyadenylation and degradation of human mitochondrial RNA: the prokaryotic past leaves its mark. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005; 25:6427–6435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nagaike T., Suzuki T., Katoh T., Ueda T.. Human mitochondrial mRNAs are stabilized with polyadenylation regulated by mitochondria-specific poly(A) polymerase and polynucleotide phosphorylase. J. Biol. Chem. 2005; 280:19721–19727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wydro M., Bobrowicz A., Temperley R.J., Lightowlers R.N., Chrzanowska-Lightowlers Z.M.. Targeting of the cytosolic poly(A) binding protein PABPC1 to mitochondria causes mitochondrial translation inhibition. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010; 38:3732–3742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wilson W.C., Hornig-Do H.T., Bruni F., Chang J.H., Jourdain A.A., Martinou J.C., Falkenberg M., Spahr H., Larsson N.G., Lewis R.J. et al. . A human mitochondrial poly(A) polymerase mutation reveals the complexities of post-transcriptional mitochondrial gene expression. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014; 23:6345–6355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bratic A., Clemente P., Calvo-Garrido J., Maffezzini C., Felser A., Wibom R., Wedell A., Freyer C., Wredenberg A.. Mitochondrial polyadenylation is a one-step process required for mRNA integrity and tRNA maturation. PLoS Genet. 2016; 12:e1006028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fiedler M., Rossmanith W., Wahle E., Rammelt C.. Mitochondrial poly(A) polymerase is involved in tRNA repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015; 43:9937–9949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Martin N.T., Nakamura K., Paila U., Woo J., Brown C., Wright J.A., Teraoka S.N., Haghayegh S., McCurdy D., Schneider M. et al. . Homozygous mutation of MTPAP causes cellular radiosensitivity and persistent DNA double-strand breaks. Cell Death Dis. 2014; 5:e1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tomecki R., Dmochowska A., Gewartowski K., Dziembowski A., Stepien P.P.. Identification of a novel human nuclear-encoded mitochondrial poly(A) polymerase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004; 32:6001–6014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Slomovic S., Schuster G.. Stable PNPase RNAi silencing: its effect on the processing and adenylation of human mitochondrial RNA. RNA. 2008; 14:310–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ojala D., Montoya J., Attardi G.. tRNA punctuation model of RNA processing in human mitochondria. Nature. 1981; 290:470–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mullen T.E., Marzluff W.F.. Degradation of histone mRNA requires oligouridylation followed by decapping and simultaneous degradation of the mRNA both 5′ to 3′ and 3′ to 5′. Genes Dev. 2008; 22:50–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schmidt M.J., West S., Norbury C.J.. The human cytoplasmic RNA terminal U-transferase ZCCHC11 targets histone mRNAs for degradation. RNA. 2011; 17:39–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Borowski L.S., Dziembowski A., Hejnowicz M.S., Stepien P.P., Szczesny R.J.. Human mitochondrial RNA decay mediated by PNPase-hSuv3 complex takes place in distinct foci. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013; 41:1223–1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Szczesny R.J., Borowski L.S., Brzezniak L.K., Dmochowska A., Gewartowski K., Bartnik E., Stepien P.P.. Human mitochondrial RNA turnover caught in flagranti: involvement of hSuv3p helicase in RNA surveillance. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010; 38:279–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pearce S.F., Rorbach J., Van Haute L., D'Souza A.R., Rebelo-Guiomar P., Powell C.A, Brierley I., Firth A.E., Minczuk M.. Maturation of selected human mitochondrial tRNAs requires deadenylation. eLife. 2017; 6:e27596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Maes A., Gracia C., Hajnsdorf E., Regnier P.. Search for poly(A) polymerase targets in E. coli reveals its implication in surveillance of Glu tRNA processing and degradation of stable RNAs. Mol. Microbiol. 2012; 83:436–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mohanty B.K., Maples V.F., Kushner S.R.. Polyadenylation helps regulate functional tRNA levels in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012; 40:4589–4603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Li Z., Reimers S., Pandit S., Deutscher M.P.. RNA quality control: degradation of defective transfer RNA. EMBO J. 2002; 21:1132–1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Anderson J.T. RNA turnover: unexpected consequences of being tailed. Curr. Biol. 2005; 15:R635–R638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Komine Y., Kwong L., Anguera M.C., Schuster G., Stern D.B.. Polyadenylation of three classes of chloroplast RNA in Chlamydomonas reinhadtii. RNA. 2000; 6:598–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bittman R. Studies of the binding of ethidium bromide to transfer ribonucleic acid: absorption, fluorescence, ultracentrifugation and kinetic investigations. J. Mol. Biol. 1969; 46:251–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wells B.D., Cantor C.R.. A strong ethidium binding site in the acceptor stem of most or all transfer RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1977; 4:1667–1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ghribi S., Maurel M.C., Rougee M., Favre A.. Evidence for tertiary structure in natural single stranded RNAs in solution. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988; 16:1095–1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chu W.C., Liu J.C., Horowitz J.. Localization of the major ethidium bromide binding site on tRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997; 25:3944–3949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Toompuu M., Yasukawa T., Suzuki T., Hakkinen T., Spelbrink J.N., Watanabe K., Jacobs H.T.. The 7472insC mitochondrial DNA mutation impairs the synthesis and extent of aminoacylation of tRNASer(UCN) but not its structure or rate of turnover. J. Biol. Chem. 2002; 277:22240–22250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yasukawa T., Suzuki T., Ueda T., Ohta S., Watanabe K.. Modification defect at anticodon wobble nucleotide of mitochondrial tRNAs(Leu)(UUR) with pathogenic mutations of mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes. J. Biol. Chem. 2000; 275:4251–4257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tiranti V., Chariot P., Carella F., Toscano A., Soliveri P., Girlanda P., Carrara F., Fratta G.M., Reid F.M., Mariotti C. et al. . Maternally inherited hearing loss, ataxia and myoclonus associated with a novel point mutation in mitochondrial tRNASer(UCN) gene. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1995; 4:1421–1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Toompuu M., Tiranti V., Zeviani M., Jacobs H.T.. Molecular phenotype of the np 7472 deafness-associated mitochondrial mutation in osteosarcoma cell cybrids. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1999; 8:2275–2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. El Meziane A., Lehtinen S.K., Hance N., Nijtmans L.G., Dunbar D., Holt I.J., Jacobs H.T.. A tRNA suppressor mutation in human mitochondria. Nat. Genet. 1998; 18:350–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Enriquez J.A., Attardi G.. Analysis of aminoacylation of human mitochondrial tRNAs. Methods Enzymol. 1996; 264:183–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. El Meziane A., Lehtinen S.K., Holt I.J., Jacobs H.T.. Mitochondrial tRNALeu isoforms in lung carcinoma cybrid cells containing the np 3243 mtDNA mutation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1998; 7:2141–2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Borner G.V., Zeviani M., Tiranti V., Carrara F., Hoffmann S., Gerbitz K.D., Lochmuller H., Pongratz D., Klopstock T., Melberg A. et al. . Decreased aminoacylation of mutant tRNAs in MELAS but not in MERRF patients. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000; 9:467–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Toompuu M., Levinger L.L., Nadal A., Gomez J., Jacobs H.T.. The 7472insC mtDNA mutation impairs 5′ and 3′ processing of tRNA(Ser(UCN)). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004; 322:803–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Richter U., Lahtinen T., Marttinen P., Suomi F., Battersby B.J.. Quality control of mitochondrial protein synthesis is required for membrane integrity and cell fitness. J. Cell Biol. 2015; 211:373–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cannino G., El-Khoury R., Pirinen M., Hutz B., Rustin P., Jacobs H.T., Dufour E.. Glucose modulates respiratory complex I activity in response to acute mitochondrial dysfunction. J. Biol. Chem. 2012; 287:38729–38740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tzoulis C., Papingji M., Fiskestrand T., Roste L.S., Bindoff L.A.. Mitochondrial DNA depletion in progressive external ophthalmoplegia caused by POLG1 mutations. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2009; 120:38–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. He L., Chinnery P.F., Durham S.E., Blakely E.L., Wardell T.M., Borthwick G.M., Taylor R.W., Turnbull D.M.. Detection and quantification of mitochondrial DNA deletions in individual cells by real-time PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002; 30:e68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Fu Y., Lian Y., Kim K.S., Zhang L., Hindle A.K., Brody F., Siegel R.S., McCaffrey T.A., Fu S.W.. BP1 homeoprotein enhances metastatic potential in ER-negative breast cancer. J. Cancer. 2010; 1:54–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Takahashi M., Haraguchi A., Tahara Y., Aoki N., Fukazawa M., Tanisawa K., Ito T., Nakaoka T., Higuchi M., Shibata S. Positive association between physical activity and PER3 expression in older adults. Sci. Rep. 2017; 7:39771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Marcel M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet J. 2011; 17:10–12. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Magoč T., Salzberg S.L.. FLASH: fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. 2011; 27:2957–2963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Altschul S.F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E.W., Lipman D.J.. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990; 215:403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Li Q.S., Gupta J.D., Hunt A.G.. Polynucleotide phosphorylase is a component of a novel plant poly(A) polymerase. J. Biol. Chem. 1998; 273:17539–17543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Yehudai-Resheff S., Hirsh M., Schuster G.. Polynucleotide phosphorylase functions as both an exonuclease and a poly(A) polymerase in spinach chloroplasts. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001; 21:5408–5416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zimmer S.L., Schein A., Zipor G., Stern D.B., Schuster G.. Polyadenylation in Arabidopsis and Chlamydomonas organelles: the input of nucleotidyltransferases, poly(A) polymerases and polynucleotide phosphorylase. Plant J. 2009; 59:88–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hirsch M., Penman S.. Post-transcriptional addition of polyadenylic acid to mitochondrial RNA by a cordycepin-insensitive process. J. Mol. Biol. 1974; 83:131–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Zylber E.A., Perlman S., Penman S.. Mitochondrial RNA turnover in the presence of cordycepin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1971; 240:588–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Gelfand R., Attardi G.. Synthesis and turnover of mitochondrial ribonucleic acid in HeLa cells: the mature ribosomal and messenger ribonucleic acid species are metabolically unstable. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1981; 1:497–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Rorbach J., Nicholls T.J., Minczuk M.. PDE12 removes mitochondrial RNA poly(A) tails and controls translation in human mitochondria. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011; 39:7750–7763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]