Abstract

Guanine-rich DNA has the potential to fold into non-canonical G-quadruplex (G4) structures. Analysis of the genome of the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum indicates a low number of sequences with G4-forming potential (249–1055). Therefore, D. discoideum is a perfect model organism to investigate the relationship between the presence of G4s and their biological functions. As a first step in this investigation, we crystallized the dGGGGGAGGGGTACAGGGGTACAGGGG sequence from the putative promoter region of two divergent genes in D. discoideum. According to the crystal structure, this sequence folds into a four-quartet intramolecular antiparallel G4 with two lateral and one diagonal loops. The G-quadruplex core is further stabilized by a G-C Watson–Crick base pair and a A–T–A triad and displays high thermal stability (Tm > 90°C at 100 mM KCl). Biophysical characterization of the native sequence and loop mutants suggests that the DNA adopts the same structure in solution and in crystalline form, and that loop interactions are important for the G4 stability but not for its folding. Four-tetrad G4 structures are sparse. Thus, our work advances understanding of the structural diversity of G-quadruplexes and yields coordinates for in silico drug screening programs and G4 predictive tools.

INTRODUCTION

Guanine-rich regions of DNA have the potential to fold into non-canonical secondary structures known as G-quadruplexes (G4). Four guanines can arrange into a square planar conformation through cyclic Hoogsteen hydrogen bonding to form a G-quartet. Two or more quartets stack on top of each other through π–π interactions stabilized by cations (generally monovalent) to form a G4 (1). Bioinformatics studies have identified hundreds of thousands of sequences with G4-forming potential in the human genome (2,3). DNA primarily exists in its canonical double-stranded form in vivo; however, situations arise throughout the cell cycle in which Watson–Crick base pairing interactions break and DNA transiently adopts a single-stranded state, thereby allowing for G4 folding (4). Compelling evidence for the in vivo existence and biological relevance of G4 structures comes from (i) their direct visualization using G4-specific antibodies and small molecules; (ii) the effect that highly specific G4 ligands exert on genomic stability; (iii) in vivo NMR, and (iv) mapping of G4-specific helicases to regions enriched for sequences with G4-forming potential (1,4–8). Biological functions of G4s may include transcriptional regulation by blocking expression of RNA polymerase, telomere protection through inhibition of telomerase and nucleases, and regulation of replication, recombination, and translation (7). Thus, G4s are promising targets for drug design, particularly for anti-cancer therapies, and a deeper understanding of their structural diversity as well as their biological functions can greatly aid the progress in this field.

The social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum is one of the simplest eukaryotic models used to study various biological processes such as signal transduction, phagocytosis, and cell death (more information can be found at http://dictybase.org). Genetic analysis of D. discoideum is relatively simple because its genome is small (∼32 × 106 bp), compact (few and small introns, small non-coding intergenic sequences), haploid, and now completely sequenced (9). In order to identify sequences with G4-forming potential, our group has developed an in-house program, called G4Hunter (3). Applying G4Hunter to the genome of D. discoideum, we found only 249 (threshold = 2) to 1055 (threshold = 1.5) G4-prone motifs, consistent with the small size and low GC content (22%) of the D. discoideum genome. Thus, the density of G4-prone sequences per kb in D. discoideum is low, 0.007 and 0.031 for the two thresholds, respectively. These figures are more than an order of magnitude lower as compared to G4 density in the human genome, 0.12 and 0.5 for the same thresholds of 2 and 1.5, respectively. Due to the scarcity of G4-prone sequences in D. discoideum, a detailed examination of correlations between their structures and biological functions will be more tractable as compared to the same work in humans, and should allow us to make fundamental discoveries of how G4 formation regulates key biological processes.

To begin our understanding of how G4 structures in D. discoideum relate to their biological functions, we set out to determine crystal structures of sequences with the highest G4-forming potential (G4Hunter score > 2.0 (3)). Structural studies of G4 DNA, especially via X-ray crystallography, are rare. To date, only human telomeric DNA (10), Oxytricha nova telomeric DNA (11,12), and a few synthetic sequences (e.g. dTGGGGT, dGGGG) (13–15) has been studied extensively via X-ray crystallography and NMR. NMR structures are also available for G4s formed by oncogene promoters for c-myc (16,17), c-kit (18) and Bcl-2 (19,20), and crystal structures have been determined for sequences from c-kit (21,22) and B-raf (23). Interestingly, the majority of crystallized monomolecular G4 structures adopt a parallel G4 topology and contain three G-quartets. Due to high diversity of naturally occurring G4 structures, atomic details of a variety of G4 folds are highly desirable.

Here, we present the crystal structure and the biophysical characterization of a 26 nt G-rich DNA sequence, termed 19wt. This sequence is found in the putative promoter region of two diverging genes in D. discoideum. According to our crystal structure, 19wt folds into an intramolecular four-quartet antiparallel G4 characterized by high thermal stability. Such quadruplexes are not common and add greatly to our understanding of G4 diversity. Guided by our crystal structure, we designed and tested eight loop mutants and discovered that loop interactions, while not essential for G4 folding, enhance and fine-tune G4 stability. Atomic details of the G4 structure discovered in our work shed light on the thermodynamics of G4 folding and allow us to feed the coordinates into computational programs for in silico drug screening studies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Oligonucleotides

All DNA sequences, listed in Table 1, were purchased from Eurogentec (Seraing, Belgium) with a Reverse-Phase Cartridge•Gold™ purification or from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, Iowa USA) with standard desalting purification. The quality of DNA was evaluated using denaturing gel electrophoresis and/or NMR. Concentration was determined via UV–vis spectroscopy at 95°C using extinction coefficients provided by the manufacturer and listed in Supplementary Table S1. Buffers most frequently used in this work are listed in Supplementary Table S2.

Table 1. DNA sequences used in this work. Mutated nucleotides are shown in bold underlined characters.

| Oligo | Mutation(s) | Loop 1 | Loop 2 | Loop 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19wt | None | GGGG | GA | GGGG | TACA | GGGG | TACA | GGGG |

| M1 | G5T | GGGG | TA | GGGG | TACA | GGGG | TACA | GGGG |

| M2 | G5T-A6T | GGGG | TT | GGGG | TACA | GGGG | TACA | GGGG |

| M3 | G5T-A6T-A22T | GGGG | TT | GGGG | TACA | GGGG | TACT | GGGG |

| M4 | C21A | GGGG | GA | GGGG | TACA | GGGG | TAAA | GGGG |

| M5 | G5T-C21A | GGGG | TA | GGGG | TACA | GGGG | TAAA | GGGG |

| M6 | G5A-C21A | GGGG | AA | GGGG | TACA | GGGG | TAAA | GGGG |

| M7 | G5T-C21T | GGGG | TA | GGGG | TACA | GGGG | TATA | GGGG |

| M8 | C13A | GGGG | GA | GGGG | TAAA | GGGG | TACA | GGGG |

Gel electrophoresis

Samples for PAGE were annealed for 5 min at 95 °C, slowly cooled and equilibrated at 4 °C overnight in 10 mM lithium cacodylate (LiCaco) buffer, pH 7.2, supplemented with 5 mM KCl and 95 mM LiCl (5K buffer) at a final concentration of ∼70 μM (per strand). Samples were weighted with sucrose (final 7 % w/v) and loaded on a 15 % native polyacrylamide gel containing 10 mM KCl; running buffer consisted of 1× Tris–borate–EDTA (TBE) and 10 mM KCl. The gel was premigrated for 30 min at 150 V at room temperature and run for 2.5 h at 150 V. Oligothymidylate markers 5′ dTn (where n = 6-100) were used as internal migration standards. DNA bands were visualized using StainsAll; pictures were taken by a conventional phone camera.

Thermal difference spectra (TDS) and isothermal difference spectra (IDS)

For all biophysical studies DNA was folded by heating at 95°C for 5 min in 10 mM LiCaco buffer at pH 7.2 supplemented with either K+ or Na+, Supplementary Table S2. These samples were cooled down slowly over a 3–4 h time period and equilibrated overnight at 4°C.

Thermal difference spectra

TDS were recorded on Secomam Uvikon XL or XS spectrophotometers thermostated with external Ecoline Staredition RE 305 or Julabo F12-ED waterbaths and an Agilent Cary 300 spectrophotometer equipped with a peltier thermal unit (temperature errors are ±0.3°C). UV-vis absorbance spectra were collected in the 220–350 nm range with 0.5 nm interval, 0.1 s averaging time, 300 nm/min scan rate, and 2 nm spectral bandwidth; automatic baseline correction was applied to all data. TDS were obtained by calculating the difference between UV–vis absorbance spectra above (95°C) and below (4°C) the melting temperature of the DNA secondary structure. In this case, given the very high stability of the G4 structure considered (see below), the structure was only partially denatured at 95°C, which did not affect the shape of the TDS. The final data was normalized for ease of comparison.

Isothermal difference spectra

For IDS, similar to TDS, the data were obtained by taking the difference between the absorbance spectra of unfolded and folded oligonucleotides. For TDS unfolded samples were prepared by thermal denaturation which normally does not happen in a biological setting. For IDS, on the other hand, unfolded DNA was prepared in 10 mM LiCaco buffer pH 7.2 and folding was induced by adding KCl. Such treatment allowed us to collect data for folded and unfolded DNA at the very same temperature (here 25°C), consistent with biological reality. The spectra were recorded in the 220 to 335 nm range with 0.2 nm interval and 200 nm/min scan rate. The folded spectra were corrected for dilution resulting from KCl addition.

DNA melting monitored by UV-vis spectroscopy

Stability of DNA at different concentrations was determined in UV–vis melting experiments by monitoring the absorbance at 295 and 335 nm using 1-cm pathlength quartz cuvettes. The former wavelength is sensitive to G4 folding state as evidenced by the prominent trough in TDS, while the latter wavelength serves as a reference to monitor instrument performance (the extinction coefficient of DNA at 335 nm is negligible). The temperature was measured with a temperature sensor inserted in the cuvette holder next to the DNA samples. The temperature change rate was 0.2°C/min. The samples of 19wt were prepared at 2 and 10 μM concentration in 5K buffer. All experiments were repeated two to three times. The data were processed by subtracting the signal at 335 nm from the signal at 295 nm. The resulting curves were smoothed using a Savitzky-Golay filter with a 13-point quadratic function in Origin 9.0. The first derivative was then taken. The temperature of half transition, T1/2, corresponds to the trough or peak on the first derivative curve as read by eye (error ±0.5°C). For reversible melting T1/2 equals (or is very close) to the melting temperature, Tm. In that case, the data were fit using a two-state model with a temperature-independent enthalpy of unfolding, ΔH (24), which yielded Tm and ΔH values and associated fitting errors.

Circular Dichroism (CD)

CD wavelength scans were collected on annealed DNA samples at 2.5–4.5 μM concentration in 1-cm quartz cuvettes at 4 or 25°C using a JASCO J-815 spectropolarimeter with a 2 nm bandwidth, 500 nm/min scan speed, 220–330 nm window, and 1 nm step. The data were also recorded on an AVIV-435 instrument with a 2 nm bandwidth, 1 s averaging time, 220–330 nm window and 1 nm step. Five scans were recorded and averaged. Data were processed as described elsewhere (25). CD scans were also collected on the samples used for crystallization.

CD melting experiments were conducted in the 25–95°C temperature range with 1°C step, 1°C/min temperature change rate, 15 s averaging time, and 5 s equilibration time. Ellipticity was monitored at 295 nm, which represents the wavelength of maximum signal in CD scans. Data were processed as described for UV–vis melting above. In this case, the reference spectra were those of buffer alone in the same cuvettes.

Crystallography

Oligonucleotide 19wt was diluted to 2 mM in 50K buffer (10 mM KCaco pH 6.5 and 40 mM KCl), annealed and equilibrated as described above. Crystallization was achieved using the hanging-drop vapor diffusion method (drop size 0.8 + 0.8 μl). Crystal trays were incubated at 12°C. Diffraction quality trigonal pyramidal crystals grew from Natrix screen condition N2-15: 80 mM NaCl, 20 mM MgCl2·6H2O, 40 mM NaCaco trihydrate pH 6.0, 35% v/v (+/–)-2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol (MPD), and 12 mM spermine tetrahydrochloride. Crystals were cryoprotected using 45% MPD, equilibrated for 1–2 min for partial dehydration, and flash frozen.

Several data sets were collected at the French synchrotron Soleil on the beamline PXII to a maximum resolution of 2.95 Å. The raw data were processed using XDS (26). The structure was solved via molecular replacement using the Phenix_MR procedure (27). A variety of G4 models were tested including mono-, di- and tetrameric G4s as well as G4s with two, three and four G-quartets. The four G-quartet quadruplex from the Oxytricha nova telomeric sequence (Protein Data Bank, PDB, code 1JRN) without connecting loops provided a successful solution in one orientation. The original model was then extensively rebuilt and completed manually in Coot (28). It was necessary to include three K+ ions equidistant from four guanine bases of two adjacent quartets during the crystallographic refinement of each G4. The unit cell contains seven G4 chains, labeled A-F and Z. Three DNA chains show some degree of disorder in the loop regions, i.e. A20 in chain B, T11–A12 in chain D and T11 to A14 in chain Z were not built in the deposited model. The summary of data collection and refinement statistics is presented in Table 2. Figures were prepared using PyMOL (29).

Table 2. Crystallographic statistics for 19wt X-ray structurea.

| Space group | C2 |

| Unit cell dimensions | |

| a, b, c (Å) | 72.06, 135.75 55.20 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 93.6, 90 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50.0–2.95 |

| (Highest resolution shell) | (3.03–2.95) |

| R merge (%) overall | 6.3 (119.0) |

| I/σ | 15.47 (1.32) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.7 |

| Redundancy | 3.41 |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution (Å) | 2.95 |

| Reflections | 10040 |

| R work/Rfree (%) | 21.8/28.7 |

| No. of atoms | 3756 |

| Nucleotides | 175 |

| Ions | 21 |

| Overall B-factor (Å2) | 83.1 |

| rms deviations | |

| Bond-lengths (Å) | 0.007 |

| Bond-angles (°) | 1.255 |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID | 6FTU |

aValues in parentheses refer to the highest resolution shell 3.03-2.95 Å.

Planarity of G-quartets, helical twist, and torsion angles

In order to calculate the planarity of each quartet and a A–T–A triad, we used principal component analysis (PCA), as described previously (30). We calculated helical twist using an in-house script which extracted the coordinates of all atoms from the PDB file and represented every guanine base as a vector from C8 to the midpoint between N1 and C2 (31). The angle between the vectors corresponding to every pair of stacked guanines was then calculated. We verified the script using a structure for which helical twist is reported (PDB code 4U5M) (31). For comparison, we also calculated the helical twist for the G4 from O. nova (PDB code 1JPQ). Finally, we calculated DNA backbone torsional angles using the 3DNA software system (32). The distribution of the torsion angles was plotted in MATLAB in the form of a wheel plot.

NMR studies

All data were collected on a Bruker Avance 700 MHz instrument. The samples were annealed at 2 mM in 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer at pH 6.9 supplemented with 40 mM KCl (KPi) and diluted to 120–200 μM in the same buffer with 10% (v/v) D2O for data collection. Data for 19wt were collected in the 278 to 353 K temperature range. All the mutants were examined under the same condition but at 298 K only.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Identification of 19wt for crystallization

Sequences with G4-forming potential are quite rare in the genome of D. discoideum and are found mainly in intergenic regions or on the complementary strand of coding exons. Following bioinformatics analysis (3), our laboratory validated the G4-forming potential of ∼200 sequences using a panel of biophysical methods; 90% of these sequences formed stable G4s in vitro (to be described elsewhere). We closely examined the sequences which (i) have high G4Hunter score, i.e. >1.5; (ii) produce thermodynamically stable G4 in vitro, i.e. with a Tm well above physiological temperature; and (iii) have characteristic G-quadruplex NMR signatures. The 26-mer sequence 5′-GGGGGAGGGGTACAGGGGTACAGGGG-3′, named 19wt, has a G4Hunter score of 2.54 and fits all the above criteria. Interestingly, 19wt is present in two identical copies in the genome of the ddAX4 strain as a result of duplication of a large ∼750 kb region on chromosome 2. 19wt can be mapped at 263 and 86 nucleotides upstream of two divergent genes (DDB_G0295833/DDB_G0273855 and DDB_G0273115/DDB_G0273853), respectively. Gene ID DDB_G0293833/DDB_G0273855 is annotated as a short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase (SDR) family protein whereas no functional annotations are available for Gene ID DDB_G0273115/DDB_G0273853. The 19wt sequence is likely to be in the promoter region due to proximity to the genes. The presence of four repeats of ≥4 guanines connected by short loops drew our attention to this sequence as such a feature was unexpected given the GC-poor content of the D. discoideum genome. Sequences with such high G4Hunter score were not found in the promoters of related genes of other amoeba whose genomes are available in Dictybase.org (D. disco, D. purpu, D. fasci or P. palli).

Biophysical characterization of 19wt for crystallization

Prior to crystallization, 19wt was thoroughly characterized via biophysical methods in the presence of physiologically relevant K+ ions. TDS (and IDS) display characteristic signatures of G4 structure, Figure 1A (33). In CD studies, the prominent peak is observed at 295 nm and the trough at 260 nm, Figure 1B, suggesting an antiparallel conformation in agreement with the crystal structure (see below). The quadruplex displays exceptionally high thermodynamic stability as expected for a G-rich sequence with a high G4Hunter score of 2.54 bearing four repeats of at least four guanines. Specifically, Tm is > 90°C under near physiological conditions (100 mM KCl) and remains above 90°C even when potassium concentration is lowered to 10 mM. A clear melting transition with a small hysteresis of 6.3°C and a T1/2 of 76.9 ± 0.5°C (determined from the heating curves) is observed in 5K buffer (with 5 mM K+). The apparent melting temperature did not change when concentration of 19wt was increased from 2 to 10 μM, in agreement with the monomolecular nature of the structure.

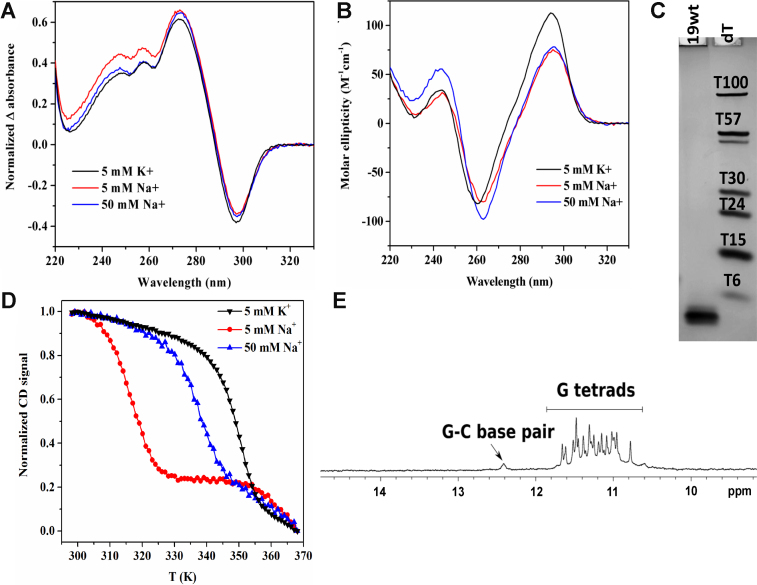

Figure 1.

Characterization of 19wt in K+ and Na+ buffers. (A) TDS, (B) CD spectra, (C) non-denaturing 20% PAGE. (D) CD melting studies monitoring signal at 295 nm in three different buffer conditions. (E) 1D 1H NMR spectrum in KPi buffer at 298 K showing imino protons for G–C base pair (∼12.4 ppm) and G quartets (∼10–12 ppm).

We have also tested folding and stability of 19wt in the presence of 5 and 50 mM Na+. The CD and TDS signatures in K+ and in Na+ are rather similar, Figure 1A–B, suggesting that 19wt adopts the same fold in both conditions. As expected, the melting temperature is significantly lower in the sodium buffer (43.8 ± 0.4°C at 5 mM Na+ and 64.1 ± 0.3°C at 50 mM Na+ versus 76.9 ± 0.5°C at 5 mM K+), see Supplementary Table S3. To the best of our knowledge, all G4 structures but one (34) display greater stability in K+ versus Na+ buffer. Interestingly in our case the Na+/K+ stability difference is rather extreme, 33.1°C at 5 mM cation concentration. To provide an element of comparison, a set of 36 G-rich oligonucleotides with different composition of the middle loop displayed on average 12.7°C higher stability in K+ as compared to Na+ (35). Similar to our case, the Na+/K+ stability difference for two oligonucleotides 5′- (G3T2)3G3-3′ and 5′-T(G3T2)3G3T-3′ is dramatic, >35°C at 100 mM cation concentration (36). These oligonucleotides, unlike in our case, also demonstrated K+-induced structural transition.

Gel electrophoresis suggested the low conformational heterogeneity and compact nature of 19wt, Figure 1C. NMR confirmed the formation a four-tetrad G4 as evidenced by the presence of at least 16 major sharp peaks in the imino region, Figure 1E. Peaks corresponding to a minor species are also observed. A G-C base pair belonging to the major conformation is clearly visible at ∼12.4 ppm.

Details of the crystal structure

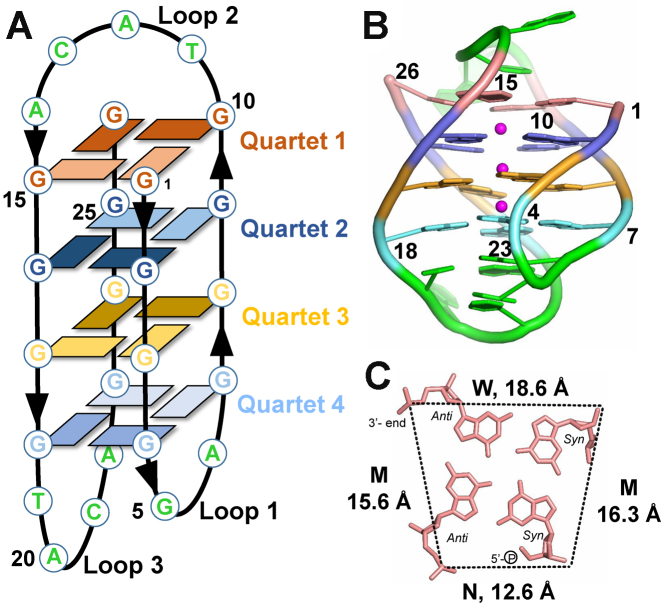

The structure of 19wt was successfully solved in the C2 space group to 2.95 Å resolution. The asymmetric unit contains seven unambiguously positioned 19wt molecules (chains A–F and Z). Each chain forms an identical G-quadruplex structure composed of four G-quartets connected by two lateral loops (loop 1 with the sequence GA and loop 3 with the sequence TACA) and one diagonal loop (loop 2 with the sequence TACA). The overall topology of 19wt is antiparallel with two parallel and two antiparallel strands (syn–syn–anti–anti glycosidic torsion angles within each quartet, see Figure 2). The G4 core is formed by the following four quartets G1⋅G10⋅G26⋅G15 (Quartet 1); G2⋅G9⋅G25⋅G16 (Quartet 2); G3⋅G8⋅G24⋅G17 (Quartet 3); and G4⋅G7⋅G23⋅G18 (Quartet 4), Figure 2. The conformation of guanines along each strand alternates, starting with 5′-Gsyn–Ganti–Gsyn–Ganti. The structure has one narrow groove (with a width of 12.6 ± 1.0 Å measured between phosphate groups), two medium grooves (15.6 ± 1.6 and 16.3 ± 0.6 Å) and one wide groove (18.6 ± 0.9 Å), Figure 2C and Supplementary Table S4. Webba da Silva and co-workers have developed a formalism for the classification of quadruplex topologies and predictions of quadruplex fold based on the combination of syn/anti glycosidic bond angles (37). Using this formalism, quadruplex formed by 19wt DNA can be classified as a type I G4 with MWMN grooves (groove width is listed starting at the 5′ end counterclockwise; M—medium, W—wide and N—narrow). The loops are designated as ld-l, where l and d indicate lateral and diagonal loops, respectively, and ‘–' indicates counterclockwise progression of the loop (note that a diagonal loop does not require a clockwise or counterclockwise prefix).

Figure 2.

Overall view of the D. discoideum G-quadruplex, 19wt. (A) Schematic representation of the G4. Dark and light rectangles indicate anti and syn conformations of guanine bases, respectively. Chain orientation is indicated by arrow heads. Each G-quartet is colored in a unique color throughout the figure. Loop nucleotides are colored in green. (B) Cartoon representation of the crystal structure with purines and pyrimidines shown as filled rings. Sugar rings are omitted for clarity. Same color coding is used as in panel A, with magenta spheres representing K+ ions. (C) Quartet 1 (G1⋅G10⋅G26⋅G15). N – narrow, M – medium, and W – wide grooves. Average groove width values are indicated. Phosphate-phosphate distances are shown as dashed lines. Nucleotides are depicted as sticks.

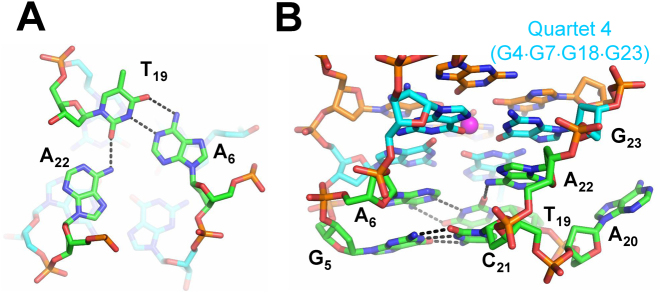

Quartets 1–2, 2–3 and 3–4 are spaced by 3.49 ± 0.07, 3.48 ± 0.04 and 3.43 ± 0.03 Å, respectively, consistent with efficient π–π stacking interactions (38). As expected, three K+ ions are found in the square antiprismatic environment formed by the O6 carbonyls with K+–O bond distances ranging from 2.5 to 3.2 Å. Potassium ions are spaced by 3.6 ± 0.3 Å (averaged over three potassium ions in all seven chains). Nucleotides from loop 1 and loop 3, which are found on the same side of the quadruplex, form an A–T–A triad composed of a Watson–Crick A6–T19 base pair and A22 base whose amine group is engaged in hydrogen bonding interactions with the O2 carbonyl of T19, Figure 3A. The spacing between the A–T–A triad and Quartet 4 is 4.0 ± 0.1 Å, again consistent with π–π stacking interactions. The A22 purine ring adopts an anti conformation, possibly driven by the optimal packing geometry imposed by the following G23, and likely leading to the expulsion of A20, Figure 3B. Another important interaction between loop nucleotide is the G5–C21 Watson–Crick base pair, which stacks onto the A6–T19–A22 triad, Figure 3B. This G–C base pair is clearly visible in the 1D 1H NMR spectrum at ∼12.4 ppm, Figure 1E. The engagement of G5 in a stable base pair with C21 likely prevents it from participating in a G-quartet, explaining the lack of conformational polymorphism expected from structures with long G-tracts. The A6 base intercalates between the bases of G4 and G5, preventing their direct stacking, thus forcing the G5 sugar ring to adopt a C3′-endo conformation. The G5–C21 base pair and the A6–T19–A22 triad are likely to contribute to the overall organization and stability of the 19wt G4. A20 is the only nucleotide in loop 3 which does not participate in any intra-G4 interactions; rather, it is flipped out and is implicated in crystal contacts, Figure 3B and Supplementary Figure S1A. Contrary to the extensive involvement of loop 1 and loop 3 nucleotides in the folding and stability of the G4 structure, of the four nucleotides in the diagonal loop 2, only C13 forms any non-covalent interactions by stacking onto G10 from Quartet 1.

Figure 3.

Molecular depiction of the interactions between loop 1 and loop 3. (A) Hydrogen bonding observed in the A6–T19–A22 triad. (B) Side view showing the stacking interactions between the G5–C21 Watson–Crick base pair, the A6–T19–A22 triad, and Quartet 4 (shown in cyan). Nucleotides are shown as sticks colored according to atom type (carbon is green, cyan or orange; nitrogen is blue, oxygen is red, and phosphate is gold). Hydrogen bonds are shown as black dashed lines.

We analyzed the distribution of backbone dihedral angles (α, β, γ, δ, ϵ and ξ) and glycosidic torsion angles (χ) and summarized the data using a wheel plot, Supplementary Figure S2A. The observed values are in good agreement with data reported for other G4 structures (38). The values of χ (clustered ∼60° for syn and ∼240° for anti conformations) support an antiparallel conformation for the 19wt G4. Unlike duplex DNA, G4 structures often have unconstrained, flexible, single-stranded loop regions (e.g. loop 2 in 19wt). The presence of such regions leads to a greater distribution of backbone dihedral angles in G4s compared to duplex DNA.

We used principal component analysis (PCA) to determine the planarity of each quartet and the A–T–A triad. PCA analysis yields out-of-plane deviation (Doop), which is the root-sum-square of the deviations of individual atoms from the mean plane, Supplementary Table S5. The results are plotted in Supplementary Figure S2B for each individual chain, A–F and Z. The data clearly indicates that Quartet 3, which is close to the center of the G4 structure, is the most planar with an average Doop of 0.8 ± 0.1 Å. In contrast, Quartet 1 and the A–T–A triad, located on opposite ends of the G4, display the strongest deviation from planarity with Doop of 1.8 ± 0.5 and 1.5 ± 0.1 Å, respectively. It is likely that the absence of a potassium ion on one side of the Quartet 1 plane combined with a limited capacity to stack with nearby nucleotides leads to this non-planarity. Such a situation is not encountered for Quartet 4, which stacks on the A–T–A triad.

With one exception (31) G4 DNA, just like B-DNA, adopts a right-handed helical twist. The helical twist between Quartets 1–2, 2–3 and 3–4 is 91 ± 6, 145 ± 3 and 89 ± 4°, respectively, Supplementary Table S6. Similar values, 95 ± 1, 149 ± 1 and 94 ± 1° for Quartets 1–2, 2–3 and 3–4, respectively, are observed for O. nova telomeric G4 which adopts overall similar fold (PDB code 1JPQ).

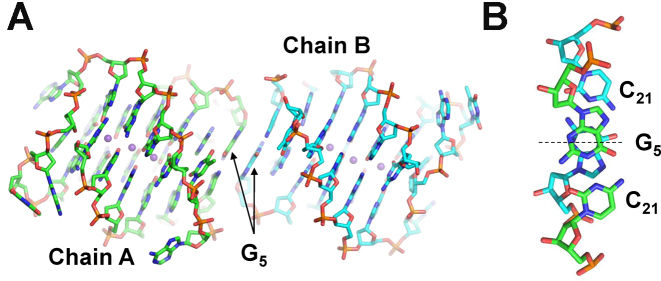

Interactions between individual G4 molecules

Three out of seven DNA chains show some degree of disorder in the loop regions, exemplified by weak electron density. Specifically, chain B is missing nt 20; chain D is missing nt 11 and 12; and chain Z is missing nt 11 to 14. The A–B, C–D and E–F pairs of chains form head-to-head dimers, while chain Z forms a dimer with the same chain from another unit cell. The dimers are held together by G5–G5 π–π stacking interactions such that the two monomers relate to each other via pseudo C2 rotation, Figure 4. All seven quadruplex molecules are highly similar as indicated by the low values of root-mean-square deviation (rmsd) for all atoms, 0.55–0.95 Å. This similarity strongly suggests that the quadruplex fold is the result of the specific DNA sequence and buffer composition (e.g. the concentration of K+) and not of the crystal packing. On the other hand, the observed dimers result from crystal packing interactions. Indeed, we believe that in solution 19wt forms a monomeric quadruplex as evidenced by its high gel mobility (Figure 1C) and the independence of its melting transition on DNA concentration (in the 2–10 μM concentration range).

Figure 4.

Inter-quadruplex contacts. (A) Two representative DNA chains, which form a dimer. The dimer is stabilized by π–π stacking interactions between G5 nucleotides. B) G5-C21 base pairs from two individual chains relate to each other via a pseudo C2 rotation axis shown as a dashed line. The axis runs between two G nucleotides and is perpendicular to the page in (A).

In addition to dimer formation, the individual chains interact with each other via π–π stacking of A20 as can be seen for chains C and A (Supplementary Figure S1A, also observed for chain F and F’, E and Z’ and Z and E’; chains related by crystallographic symmetry are indicated with a ’). Finally, C13 from one chain forms a base pair with A14 from a nearby chain; this base pair π–π stacks onto the symmetry related base pair, Supplementary Figure S1C.

NMR characterization of 19wt loop mutants

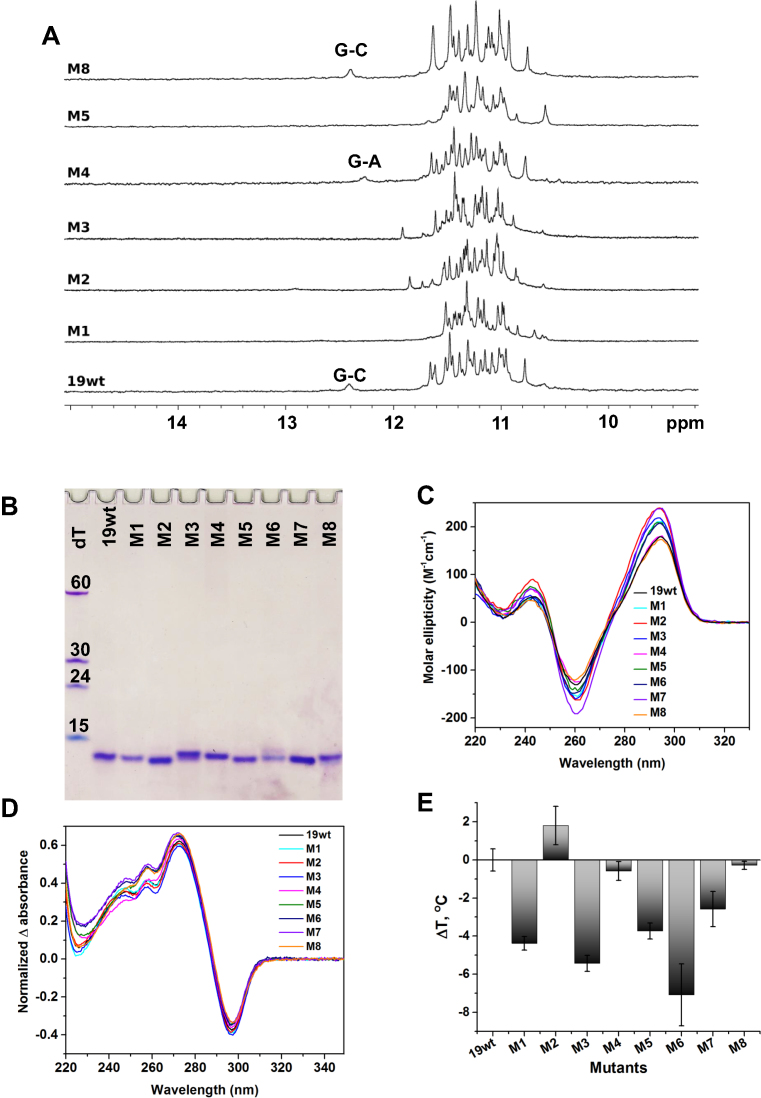

In order to confirm that the structure of 19wt observed in the crystalline form is maintained in solution, we designed eight loop mutants (Table 1) and tested the interactions involving loop nucleotides via solution 1H NMR (Figure 5A). As mentioned above, the signal at ∼12.4 ppm originates from a G5–C21 base pair consistent with the observed X-ray structure. Subsequently, a G-to-T mutation at position 5 (present in all mutants but M4 and M8) disrupts the G-C base pair leading to disappearance of the imino signal at ∼12.4 ppm. Interestingly, a C-to-A mutation at position 21 (in the M4 mutant) which should also eliminate the G5–C21 base pair leads to a spectrum with a clear peak at ∼12.2 ppm. This peak may reflect the formation of a non-canonical G5–A21 base pair. In order to investigate the thermal stability of the G5–C21 base pair in 19wt, we acquired NMR spectra in the temperature range from 25 to 80°C (Supplementarys Figure S3A). The signal for the G5–C21 base pair started to decrease at 50°C, and completely disappeared above 60°C while the signals for imino protons from the G-quartets were still intact. This finding is consistent with CD thermal stability studies indicating that in the presence of 50 mM K+, Tm of the 19wt G4 is well above 90°C.

Figure 5.

Biophysical and 1H NMR characterization of 19wt and its loop mutants. (A) 1H NMR spectra at 700 MHz and 298 K. The oligonucleotides were prepared at 120–200 μM in KPi buffer and 10% D2O. (B) Non-denaturing 15% PAGE. Samples were prepared at 70 μM in 5K buffer. (C) CD spectra. All mutants with G5A or G5T mutations (M1–M3 and M5–M7) have a slightly increased CD intensity at 295 nm while the CD signatures of M4 and M8 are nearly identical to that of 19wt. (D) TDS. (E) Bar graph of ΔTm (relative to 19wt) determined via CD melting studies. For C–E, the samples were 2.5–4.5 μM in 5K buffer.

Based on the crystal structure, we expected to observe the imino proton resonance of T19 involved in the A–T–A triad at ∼13.5 ppm. We were not able to detect this interaction, even when the temperature was lowered to 5°C (Supplementary Figure S3B). This result is possibly due to an intermediate regime of the conformational motions within the triad that are unfavorable for NMR detection.

In short, our NMR data support the presence of a G5–C21 base pair observed in the crystal structure and confirm the high stability of the 19wt G4.

Biophysical characterization of 19wt loop mutants

We proceeded to assess the importance of interactions between loop nucleotides for the overall formation and stability of the 19wt G4 using a panel of biophysical methods. Analysis of the PAGE gel (Figure 5B) indicates that 19wt and all mutants run with similar mobility and faster than the dT15 marker, suggesting that none of the designed mutations affect the overall capacity of 19wt to fold into a compact, monomolecular G4. CD and TDS (Figure 5C and 5D) support this conclusion, demonstrating that the signatures for the mutants and 19wt are rather similar. We then hypothesized that interactions between loop nucleotides could be important for G4 stability and tested this hypothesis using CD thermal studies, Figure 5E and Table 3. Small but significant destabilizing effects (up to ∼7°C) were observed for most of the mutations affecting the G5-C21 base pair. Interestingly, the stability of the M2 mutant with G5T–A6T mutations where both the G5–C21 base pair and the A6–T19–A22 triad are affected, is comparable (and somewhat higher) to that of 19wt. It is possible that this double mutant has new sets of compensating non-covalent interactions, (e.g. T6-A22 base pair). Such a situation is reminiscent of the one found for the M4 sequence (C21A) whose stability is unaltered by the mutation (ΔTm = −0.6°C). As was suggested above using NMR data, for this mutant, the G5–C21 base pair could be potentially replaced by a G–A pair maintaining the original stability of the structure. In an attempt to prevent any interactions involving nucleotides from loops 1 and 3 without truncating the loops, we generated the M3 triple mutant (G5T–A6T–A22T), where the G5–C21 base pair and the A6–T19–A22 triad should be disrupted. As predicted, the G4 formed by this sequence had one of the lowest stabilities (ΔTm = –5.4°C). Finally, the stability of the M8 sequence with a C13A mutation is similar to that of 19wt (ΔTm = −0.3°C) suggesting that stacking of the C13 nucleotide over Quartet 1 does not play an important role in G4 formation and overall stability. Note that the C13–A’14 base pair (Supplementary Figure S2) will not be affected as we believe that such interaction is due to crystal packing forces and is not present in solution.

Table 3. Thermodynamic parameters for 19wt and its mutants in 5K buffer.

| Name | Mutation | Potentially affecting | T m (°C)b | ΔTm (°C) | Hysteresis (°C)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19wt | None | – | 76.7 ± 0.6 | – | 6.4 |

| M1 | G5T | G5–C21 base pair | 72.3 ± 0.4 | −4.4 | 4.2 |

| M2 | G5T–A6T | G5–C21 and A6–T19 base pairs | 78.5 ± 1.0 | +1.8 | 6.1 |

| M3 | G5T–A6T–A22T | G5–C21 base pair and A6–T19–A22 triad | 71.3 ± 0.4 | −5.4 | 4.7 |

| M4 | C21A | G5–C21 base pair | 76.1 ± 0.5 | −0.6 | 7.3 |

| M5 | G5T–C21A | G5–C21 base pair: both nta | 73.0 ± 0.4 | −3.7 | 4.7 |

| M6 | G5A–C21A | G5–C21 base pair: both nt | 69.6 ± 1.6 | −7.1 | 6.7 |

| M7 | G5T–C21T | G5–C21 base pair: both nt | 74.1 ± 0.9 | −2.6 | 4.5 |

| M8 | C13A | π–π stacking between C13 and Quartet 1 | 76.4 ± 0.3 | −0.3 | 6.2 |

aNote the possibility of forming a new T–A Watson–Crick base pair.

b T m was measured from heating curves only.

cHysteresis refers to the difference in Tm measured from heating and cooling profiles; the latter is systematically shifted towards lower temperatures by 4.2 to 7.3°C.

In summary, our biophysical studies suggest that the crystal structure of 19wt represents the major conformation of the G4 found in solution and that the observed interactions between loop 1 and loop 3 positively contribute to the stability of the formed G4, although they are not essential per se for G4 folding. Thermal stability data also suggest that alteration of some loop–loop interactions might lead to the formation of stabilizing non-canonical base pairs. It is important to recognize and understand the specific interactions between nucleotides in the loops as such elements could be used as recognition sites in drug design efforts.

Comparison of 19wt with other four-quartet, biologically relevant G4 structures

A search of the PDB (https://www.rcsb.org/pdb/search/advSearch.do?search=new) with the query ‘quadruplex’ yields 283 structures. Two hundred and fifty of them are canonical quadruplexes (formed by DNA or RNA alone or in complex with proteins); quadruplexes with quartets containing bases other than guanine (A, T, C); and quadruplexes with modified bases (e.g. locked nucleic acids, 8-bromo guanine). This list also includes quadruplex-duplex hybrids, i-motifs, and tetrastranded structures composed of G⋅C⋅G⋅C quartets. The other 33 structures do not contain actual quadruplexes. A search of the Nucleic Acids Database produces a similar list (see Supporting Information). Upon visual examination of the PDB files, 59 of the structures, formed by 17 unique nucleotide sequences, contain four G-quartets. Among these entries we find a number of tetramolecular G4s formed by dTGGGGT or dGGGG (13–15). These G4s play important roles as model structures and find applications in DNA nanotechnology (39) but are less likely to be biologically relevant, at least at the genomic level. Thirty five out of 59 reported G4 structures with four G-tetrads are dimers formed by the O. nova telomeric repeat dG4T4G4; the structures were solved by NMR (representative examples include PDB codes 156D, 230D and 1K4X) and X-ray crystallography (examples include 1JB7, 1JRN, 1JPQ). Regardless of the central monovalent cation, dG4T4G4 forms an antiparallel G4 with syn–syn–anti–anti glycosidic torsion angles within each quartet and two diagonal TTTT loops. The first T base at the 5′ and 3′ ends stacks onto the terminal quartet, enhancing the stability of the structure (12).

Biologically relevant monomolecular G4s with four G-quartets are sparse and only three examples of such structures can be found in the PDB. Phan's laboratory reported X-ray and solution NMR structures of the left-handed Z-G4 formed by a modified version of an anti-proliferative oligonucleotide AGRO100 dT(GGT)4TG(TGG)3TGTT (PDB codes 4U5M and 2MS9). This four-quartet all parallel G4 is formed by two G-blocks each with two quartets connected by single nucleotide T loops (31). The second example is a solution NMR structure of d(GGGGCC)4 from the C9orf72 non-coding region (involved in ALS/FTD neurodegenerative disorders) published by Plavec's laboratory (PDB code 2N2D). The observed G4 is antiparallel with syn-anti-syn-anti glycosidic torsion angles within each quartet. The quartets are linked by three lateral C-C loops; one nucleotide of each loop is stacked onto a terminal G-quartet, yielding a stable, compact structure (40). The third example is a solution NMR structure of two antiparallel four-quartet G4s formed by dG4TxG4T4G4A2G4 (where x = 2 or 3) deposited in PDB by the Webba da Silva's group (PDB codes 2M6W and 5J6U, to be published). One more sequence could be added to this list, 36-nt RNA motif called sc1, identified via in vitro selection to bind to the human fragile X mental retardation protein. Sc1 consists of duplex and G4 components. The topology of the G4 is unique: the bottom two G-quartets are parallel-stranded while the third G-quartet is inverted; the fourth quartet is formed by U⋅A⋅U⋅G and serves as a transition between the G4 and the duplex parts of sc1 (PDB code 2LA5) (41). A few other four-quartet quadruplexes exist, but they contain locked and other unnatural nucleic acids (42). The monomolecular G4 in this work formed by 19wt sequence resembles most closely the overall structure of the bimolecular G4 formed by dG4T4G4 in the orientation of stands, number of G-tetrads, and guanine torsion angles in the G4 core.

Based on this short survey, we can conclude that four-quartet intramolecular G4s are rare, implying the low likelihood of their occurrence. Several reasons can be put forward. First, the formation of a four-quartet G4 requires four stretches of four or more guanines, which are not as frequently found in genomes as three guanine repeats. Next, in vitro (and in vivo) such DNA sequences can display high structural heterogeneity, yielding both four-quartet quadruplexes and a variety of three-quartet quadruplexes with multiple possible G–G pairings. Such heterogeneous mixtures present significant challenges for structural characterization.

CONCLUSION

In this work, we presented the crystal structure and biophysical characterization of a four-quartet antiparallel G4 formed by the 19wt sequence from D. discoideum. In addition to π–π stacking, the G4 core in 19wt is stabilized by multiple loop-loop interactions, most notably the G–C base pair stacked upon the A–T–A triad, stacked, in turn, upon Quartet 4. These loop-loop interactions do not affect the overall topology of the G4 but fine-tune its stability. The structure of 19wt adds to a handful of reported examples of monomolecular four-quartet G4 structures and expands our knowledge of G4 diversity. Our atomic resolution model, complemented by the extensive biophysical characterization, contributes to a deeper understanding of the determinants of G4 folding. Our coordinates are invaluable for the improvement of current G4 predictive tools as well as for in silico drug screening algorithms against quadruplex targets.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Atomic coordinates and structure factors for the reported crystal structure has been deposited in the PDB under accession number 6FTU.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Barrett Powell (Swarthmore) for his help with PCA analysis and the survey of the PDB for four-tetrad G4 structures. We also want to thank Sebastien Fribourg for the use of crystallography equipment and the IECB BPCS technical platform for NMR instrumentation. We acknowledge the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility and staff members for assistance in using beamline ID14-1 and ID29. We also acknowledge the Synchrotron SOLEIL for providing access to the Proxima-1 beamline. We thank Natacha Perebaskine and Alexandra Carolin Seefeldt for diffraction data collection.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

National Institutes of Health [1R15CA208676-01A1] and Henry Dreyfus Teacher-Scholar award (to L.A.Y.); Ligue Régionale contre le Cancer; Comité de Gironde; and SYMBIT project [CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/15_003/0000477] financed by the ERDF (to J.L.M.); Worldwide Cancer Research [14-0346] and Inserm (to S.T.). Funding for open access charge: Swarthmore College, National Institutes of Health; Inserm.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bochman M.L., Paeschke K., Zakian V.A.. DNA secondary structures: stability and function of G-quadruplex structures. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2012; 13:770–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Huppert J.L., Balasubramanian S.. Prevalence of quadruplexes in the human genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005; 33:2908–2916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bedrat A., Lacroix L., Mergny J.-L.. Re-evaluation of G-quadruplex propensity with G4Hunter. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016; 44:1746–1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lipps H.J., Rhodes D.. G-quadruplex structures: in vivo evidence and function. Trends Cell Biol. 2009; 19:414–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tarsounas M., Tijsterman M.. Genomes and G-quadruplexes: for better or for worse. J. Mol. Biol. 2013; 425:4782–4789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Murat P., Balasubramanian S.. Existence and consequences of G-quadruplex structures in DNA. Curr. Opin. Gen. Dev. 2014; 25:22–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rhodes D., Lipps H.J.. G-quadruplexes and their regulatory roles in biology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015; 43:8627–8637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Salgado G.F., Cazenave C., Kerkour A., Mergny J.-L.. G-quadruplex DNA and ligand interaction in living cells using NMR spectroscopy. Chem. Sci. 2015; 6:3314–3320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Eichinger L., Pachebat J.A., Glockner G., Rajandream M.A., Sucgang R., Berriman M., Song J., Olsen R., Szafranski K., Xu Q. et al. The genome of the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum. Nature. 2005; 435:43–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Phan A.T. Human telomeric G-quadruplex: structures of DNA and RNA sequences. FEBS J. 2010; 277:1107–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kang C., Zhang X., Ratliff R., Moyzis R., Rich A.. Crystal structure of four-stranded Oxytricha telomeric DNA. Nature. 1992; 356:126–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Haider S., Parkinson G.N., Neidle S.. Crystal structure of the potassium form of an Oxytricha nova G-quadruplex. J. Mol. Biol. 2002; 320:189–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Clark G.R., Pytel P.D., Squire C.J.. The high-resolution crystal structure of a parallel intermolecular DNA G-4 quadruplex/drug complex employing syn glycosyl linkages. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012; 40:5731–5738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Clark G.R., Pytel P.D., Squire C.J., Neidle S.. Structure of the first parallel DNA quadruplex-drug complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003; 125:4066–4067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Phillips K., Dauter Z., Murchie A.I.H., Lilley D.M.J., Luisi B.. The crystal structure of a parallel-stranded guanine tetraplex at 0.95Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 1997; 273:171–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mathad R.I., Hatzakis E., Dai J., Yang D.. c-MYC promoter G-quadruplex formed at the 5′-end of NHE III1 element: insights into biological relevance and parallel-stranded G-quadruplex stability. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011; 39:9023–9033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ambrus A., Chen D., Dai J., Jones R.A., Yang D.. Solution structure of the biologically relevant G-quadruplex element in the human c-MYC promoter. Implications for G-quadruplex stabilization. Biochemistry. 2005; 44:2048–2058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kuryavyi V., Phan A.T., Patel D.J.. Solution structures of all parallel-stranded monomeric and dimeric G-quadruplex scaffolds of the human c-kit2 promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010; 38:6757–6773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dai J., Dexheimer T.S., Chen D., Carver M., Ambrus A., Jones R.A., Yang D.. An intramolecular G-quadruplex structure with mixed parallel/antiparallel G-strands formed in the human BCL-2 promoter region in solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006; 128:1096–1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Agrawal P., Lin C., Mathad R.I., Carver M., Yang D.. The major G-quadruplex formed in the human BCL-2 proximal promoter adopts a parallel structure with a 13-nt loop in K+ solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014; 136:1750–1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wei D., Husby J., Neidle S.. Flexibility and structural conservation in a c-KIT G-quadruplex. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015; 43:629–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wei D., Parkinson G.N., Reszka A.P., Neidle S.. Crystal structure of a c-kit promoter quadruplex reveals the structural role of metal ions and water molecules in maintaining loop conformation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012; 40:4691–4700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wei D., Todd A.K., Zloh M., Gunaratnam M., Parkinson G.N., Neidle S.. Crystal structure of a promoter sequence in the B-raf gene reveals an intertwined dimer quadruplex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013; 135:19319–19329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ramsay G.D., Eftink M.R.. Analysis of multidimensional spectroscopic data to monitor unfolding of proteins. Methods Enzymol. 1994; 240:615–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bhattacharjee A.J., Ahluwalia K., Taylor S., Jin O., Nicoludis J.M., Buscaglia R., Chaires J.B., Kornfilt D.J.P., Marquardt D.G.S., Yatsunyk L.A.. Induction of G-quadruplex DNA structure by Zn(II) 5,10,15,20-tetrakis(N-methyl-4-pyridyl)porphyrin. Biochimie. 2011; 93:1297–1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kabsch W. Automatic processing of rotation diffraction data from crystals of initially unknown symmetry and cell constants. J. Appl. Cryst. 1993; 26:795–800. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Adams P.D., Afonine P.V., Bunkoczi G., Chen V.B., Davis I.W., Echols N., Headd J.J., Hung L.-W., Kapral G.J., Grosse-Kunstleve R.W. et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Cryst. 2010; D66:213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Emsley P., Lohkamp B., Scott W.G., Cowtan K.. Features and development of coot. Acta Cryst. 2010; D66:486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. Schrödinger, LLC; Version 1.7.5.0. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nicoludis J.M., Miller S.T., Jeffrey P.D., Barrett S.P., Rablen P.R., Lawton T.J., Yatsunyk L.A.. Optimized end-stacking provides specificity of N-methyl mesoporphyrin IX for human telomeric G-quadruplex DNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012; 134:20446–20456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chung W.J., Heddi B., Schmitt E., Lim K.W., Mechulam Y., Phan A.T.. Structure of a left-handed DNA G-quadruplex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2015; 112:2729–2733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lu X.-J., Olson W.K.. 3DNA: a versatile, integrated software system for the analysis, rebuilding and visualization of three-dimensional nucleic-acid structures. Nat. Protoc. 2008; 3:1213–1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mergny J.-L., Phan A.-T., Lacroix L.. Following G-quartet formation by UV-spectroscopy. FEBS Lett. 1998; 435:74–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Saintomé C., Amrane S., Mergny J.-L., Alberti P.. The exception that confirms the rule: a higher-order telomeric G-quadruplex structure more stable in sodium than in potassium. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016; 44:2926–2935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Guédin A., Alberti P., Mergny J.-L.. Stability of intramolecular quadruplexes: sequence effects in the central loop. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009; 37:5559–5567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Largy E., Marchand A., Amrane S., Gabelica V., Mergny J.-L.. Quadruplex turncoats: cation-dependent folding and stability of quadruplex-DNA double switches. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016; 138:2780–2792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Karsisiotis A.I., O’Kane C., Webba da Silva M.. DNA quadruplex folding formalism – a tutorial on quadruplex topologies. Methods. 2013; 64:28–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Parkinson G.N. Neidle S, Balasubramanian S. Quadruplex Nucleic Acids. 2006; The Royal Society of Chemistry; 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yatsunyk L.A., Mendoza O., Mergny J.-L.. ‘Nano-oddities’: Unusual nucleic acid assemblies for DNA-Based nanostructures and nanodevices. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014; 47:1836–1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Brčić J., Plavec J.. Solution structure of a DNA quadruplex containing ALS and FTD related GGGGCC repeat stabilized by 8-bromodeoxyguanosine substitution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015; 43:8590–8600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Phan A.T., Kuryavyi V., Darnell J.C., Serganov A., Majumdar A., Ilin S., Raslin T., Polonskaia A., Chen C., Clain D. et al. Structure-function studies of FMRP RGG peptide recognition of an RNA duplex-quadruplex junction. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2011; 18:796–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nielsen J.T., Arar K., Petersen M.. Solution structure of a locked nucleic acid modified quadruplex: introducing the V4 folding topology. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2009; 48:3099–3103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Atomic coordinates and structure factors for the reported crystal structure has been deposited in the PDB under accession number 6FTU.