Abstract

Background

An accurate and valid caries prevention policy is absent in Zhejiang because of insufficient data. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate oral health status and related risk factors in 12- to 14-year-old students in Zhejiang, China.

Material/Methods

Using multi-stage, stratified, random sampling, we recruited a total of 4860 students aged 12 to 14 years old from 6 regions in Zhejiang in this cross-sectional study. Dental caries was measured using the Decayed, Missing and Filled Teeth (DMFT) index and the Significant Caries Index (SiC). Information concerning family background and relevant behaviors was collected in a structured questionnaire. Logistic regression analysis was used to study risk factors related to dental caries.

Results

The overall prevalence of dental caries was 44% and the mean DMFT and SiC scores were 1.14 and 3.11, respectively. Female students had a higher level of dental caries than male students (P<0.01). The annual increase in caries prevalence was 3% with increasing age, and the DMFT score was 0.15. The results of logistic regression analysis showed that female sex, older age, snacks consumption once or more per day, fair or poor self-assessment of dental health, toothache experience, and dental visits were the most significant risk factors for dental caries, with odds ratios ranging from 1.24 to 2.25 (P<0.01).

Conclusions

The prevalence of dental caries in 12- to 14-year-old students in Zhejiang was low, with a tendency to increase compared with previous oral surveys. Female sex, older age, increased sugar intake, poor oral health self-assessment, and bad dental experience were the most important factors increasing dental caries risks.

MeSH Keywords: China, Dental Caries, Questionnaires, Risk Factors, Students

Background

Dental caries is a highly prevalent chronic and cumulative disease, which affects 60% to 90% of school children and many adults worldwide [1]. If left untreated, dental caries can cause severe pain and infection [2], which affects children’s school attendance and performance [3], as well as quality of life [4,5]. However, dental treatment for oral diseases is extremely costly and can be a major socioeconomic burden on individuals and health care systems [6].

Dental caries is a dynamic disease process of tooth destruction [2]. The eventual outcome of caries is determined by the balance between demineralization and remineralization, which are carried out in the interface between tooth hard tissue and the oral environment [7]. Pathological factors cause tooth decay, while protective factors (including fluoride use, healthy diet, good oral habits, and pit and fissure sealing) inhibit or even reverse demineralization. This means that dental caries is a preventable disease [8].

Although the global level of dental caries in children has declined significantly over the last 30 years, great variations in the prevalence of caries exist between and within populations [9]. Some epidemiological data concerning dental caries status in Zhejiang were mentioned in the national-level Chinese Oral Survey [10], but these data are insufficient to serve as baseline data for oral health at the provincial level. In the past decade, Zhejiang province experienced an average annual economic growth rate as high as 11.5%. Such rapid socioeconomic changes resulted in a remarkable influence on lifestyle and oral health.

Therefore, updated and detailed information on oral health status and related risk factors is essential to local government in developing realistic and effective policies for disease prevention and care health. A cross-sectional oral survey and questionnaire survey were performed between December 2015 and June 2016 to investigate oral health and related risk factors among 12- to 14-year-old students in Zhejiang province.

Material and Methods

Ethical considerations

The Oral Health Survey scheme in Zhejiang was approved by the Stomatological Ethics Committee of the Chinese Stomatological Association and the Ethics Committee of Stomatology Hospital Affiliated to Zhejiang University School of Medicine (No. 2014-003).

Sampling

The following formula was used to calculate the required sample size:

Where n is the sample size; deff is the design effect set as 4.5; p is the dental caries prevalence (28.9% as reported by the Third National Oral Survey); μ is the level of confidence; and e is the margin of error. The non-response rate was 5%. Based on this estimation, the final sample size of 12- to 14-year-old students was 4485.

This cross-sectional study was included in the Fourth National Oral Health Survey in China from 2015 to 2016, in which Zhejiang was one of the sampling provinces. Multi-stage, stratified, random sampling was used to select participants who were representative of the province’s population.

In the first stage, 3 districts and 3 counties, all in Zhejiang, were randomly selected by the probability-proportional-to-size sampling (PPS) using the varied population sizes method. In the second stage, 3 junior middle schools in each district or county were randomly selected using the PPS method. In the last stage, 270 students between 12 and 14 years old were recruited from each school, using a quota sampling method. There were 4860 students in the final sample.

Eligibility criteria of the participants were: 1. Attending school on the day of the oral survey; 2. Age between 12 and 14 years; 3. Informed consent obtained from each student and their parents.

Clinical examination

All students received a clinical assessment according to the methods and criteria provided by the WHO Oral Health Surveys [11]. In the general information section, the following information was recorded: ID, name, sex, date of birth, census register (urban or rural), and ethnic group. Oral examinations were performed by 3 trained and calibrated dentists, and another 3 dentists recorded the results. The examination was performed in a mobile dental chair under a portable light using disposable plane mouth mirrors and Community Periodontal Index (CPI) probes, with the participants in a supine position.

Dental caries status was evaluated through use of the following indexes: Decayed Teeth (DT); Missing Teeth (MT); Filled Teeth (FT); and Decayed, Missing due to caries, and Filled Teeth (DMFT). Dental injury, pit and fissure sealing, gingival bleeding, and calculus after probing were scored as “1=present” or “0=absent” by assessing all the permanent teeth. The percentage of students with DMFT >0 was used as the prevalence of dental caries. Moreover, the Significant Caries Index (SiC) was calculated as the mean DMFT for the one-third of students with the highest caries scores [12].

Questionnaire survey

All participants were asked to complete a structured questionnaire after the clinical examination. The questionnaire covered family background (single child or not, parents’ education level); oral behavior (tooth brushing, fluoride toothpaste or dental floss usage); knowledge, attitude, and dietary habits related to oral health; dental experience (toothache, dental injury, dental visit); and self-assessment of general health and oral health. The dental knowledge survey consisted of 8 questions, with a “yes or no” answer: a. “Is gum bleedings normal when brushing teeth?”; b. “Is gum infection caused by bacteria?”; c. “Is Brushing the teeth useless in preventing gum infection?”; d. Are dental caries caused by bacteria?”; e. “Are dental caries caused by sugar?”; f. “Is fluoride useless for tooth protection?”; g. “Does pit and fissure sealant protect the teeth?”; and h. “Is general health influenced by oral diseases?”. Oral health attitude was evaluated through 4 statements on the importance of oral health in the quality of life, the necessity of regular dental inspection, heredity of tooth quality, and the importance of individual effort in dental protection. Dental knowledge and attitude scores were computed by counting the total number of correct or positive replies.

Quality control

Before the survey, 3 examiners were trained in theoretical and clinical knowledge by a standard examiner. Then, each examiner was calibrated with the standard examiner and the other examiner by assessing 15 students, until the Kappa values used to determine inter-examiner reproducibility were >0.85. Additionally, 5% of the samples were randomly re-examined for an oral survey of each school, and the Kappa values were recorded to monitor inter-examiner reproducibility.

Statistical analysis

All data were statistically analyzed using SPSS Statistics Version 20.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY). Chi-square analyses were performed to assess the differences among different groups in the prevalence of dental caries experience, filling rate, pit and fissure sealing, dental injury, gingival bleeding on probing, and calculus rate. The comparison of the mean DT, MT, FT, DMFT, and SiC scores between different groups were tested by Mann-Whitney U tests or Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis, since these caries scores were not normally distributed. The association between dental caries prevalence and caries risk factors were examined through logistic regression analysis. The results of analysis are expressed in odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). Values of P<0.05 were considered statistically significant in all tests.

Results

A total of 4815 students aged 12 to 14 years old were investigated in this study, with a response rate of 99.1%. The reliability of oral health status as measured by Kappa statistics ranged from 0.87 to 0.96. The overall prevalence of dental caries was 44%, and the mean DMFT and SiC were 1.14 and 3.11, respectively. The prevalence of oral diseases and dental caries scores was evaluated in different groups divided by sex, residence location, and age (Table 1).

Table 1.

Prevalence of oral diseases and dental caries scores in different groups classified by gender, residence location and ages.

| N (%) | Preva-lence (%) | DT | MT | FT | DMFT (SD) | SiC (SD) | Filling rate (%) | Pit and fissure sealing (%) | Tooth injure (%) | Gum bleeding (%) | Calculus (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 4815 (100) | 44.0 | 0.75 | 0.01 | 0.38 | 1.14 (1.90) | 3.11 (2.19) | 33.6 | 11.1 | 3.4 | 23.1 | 28.1 |

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Male | 2397 (49.8) | 38.0** | 0.63** | 0.01 | 0.24** | 0.88 (1.57)** | 2.49 (1.82)** | 27.3** | 10.6 | 4.4** | 25.4** | 32.0** |

| Female | 2418 (50.2) | 50.0 | 0.87 | 0.01 | 0.52 | 1.41 (2.16) | 3.72 (2.35) | 37.5 | 11.6 | 2.5 | 20.7 | 24.2 |

| Residence location | ||||||||||||

| Urban | 1395 (29.0) | 43.9 | 0.61** | 0.01 | 0.47** | 1.09 (1.76) | 2.95 (1.95) | 43.3** | 23.1** | 3.9 | 19.9** | 25.9** |

| Rural | 3420 (71.0) | 44.1 | 0.81 | 0.01 | 0.35 | 1.17 (1.96) | 3.17 (2.28) | 30 | 6.2 | 3.2 | 24.3 | 29.0 |

| Age | ||||||||||||

| 12-year-old | 1433 (29.8) | 40.9 | 0.66* | 0.01 | 0.32 | 0.98 (1.71)* | 2.73 (2.01)** | 32.8 | 10.3 | 4.3 | 21.1 | 23.7 |

| 13-year-old | 1696 (35.2) | 43.9 | 0.76 | 0.01 | 0.37 | 1.14 (1.86)* | 3.10 (2.09)** | 32.8 | 12.3 | 3.2 | 22.8 | 26.5** |

| 14-year-old | 1686 (35.0) | 46.9** | 0.83** | 0.01 | 0.44 | 1.28 (2.08)** | 3.44 (2.38)** | 35.0 | 10.6 | 2.9* | 25.0* | 33.3** |

P<0.05,

P<0.01: male compared with female, urban compared with rural, 12-year-old compared with 13-year-old, 13-year-old compared with 14-year-old and 14-year-old compared with 12-year-old, respectively.

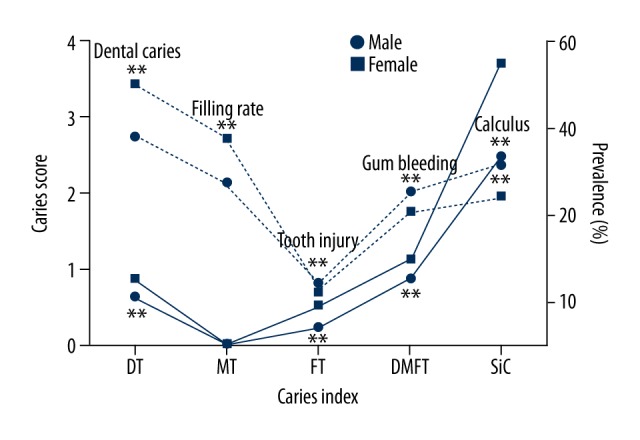

Female students showed a significantly higher DT, FT, DMFT scores, prevalence of dental caries, and filling rate (P<0.01) compared to male students. On the contrary, boys had a higher prevalence of dental injury, gingival bleeding, and calculus (P<0.01) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Dental caries scores and oral diseases prevalence by sex (** P<0.01).

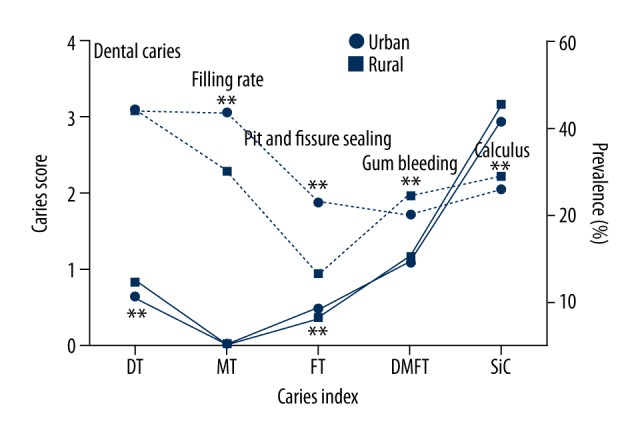

Differences between different residence locations were found regarding DT, FT scores, filling rate, pit and fissure sealing rate, and prevalence of gingival bleeding (P<0.01). However, DMFT, SiC scores, prevalence of dental caries, and calculus showed no differences between urban and rural students (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Dental caries scores and oral diseases prevalence in different resident locations (** P<0.01).

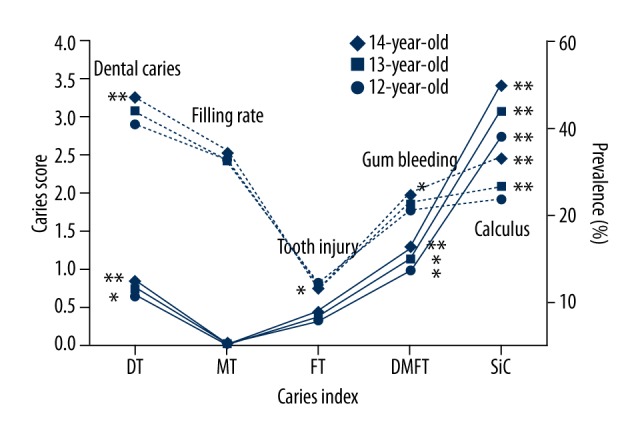

DMFT, SiC scores, prevalence of dental caries, calculus (P<0.01) and gingival bleeding (P<0.05) increased with increasing age. The 14-year-old students had the highest prevalence of dental caries (46.9%), gingival bleeding (25.0%), calculus (33.3%), the top DMFT (1.28) and SiC scores (3.44), compared with the rest of the students (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Dental caries scores and oral diseases prevalence in 12- to 14-year-old students. (* P<0.05, ** P<0.01: 12-year-olds compared with 13-year-olds, 13-year-olds compared with 14-year-olds, and 14-year-olds compared with 12-year-olds.)

There were 4700 students involved in the questionnaire survey, which corresponds to a response rate of 97.6%. Table 2 shows the risk factors associated with dental caries status. Students who brushed their teeth twice or more per day, or who consumed snacks (P<0.01) or drinks containing sugar (P<0.05) once or more per day, had a higher prevalence of dental caries and higher DMFT scores. The participants with a good self-assessment of general health or oral health showed a lower prevalence of dental caries and had lower DMFT scores (P<0.01), compared to those with fair or poor self-assessments. Students who experienced toothache, visited the dentist, and underwent dental treatment in the previous 12 months (P<0.01) had a higher level of dental caries status.

Table 2.

Prevalence of dental caries and DMFT scores associated risk factors according to the questionnaire.

| N (%) | % DMFT >0 | P | DMFT (SD) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single child | 0.262 | 0.262 | |||

| Yes | 2113 (45) | 43.4 | 1.12 (1.86) | ||

| No | 2587 (55) | 45.1 | 1.19 (1.96) | ||

| Father’s education | 0.674 | 0.512 | |||

| ≤9 year’s education | 2774 (59) | 44.4 | 1.14 (1.87) | ||

| >9year’s education | 1176 (25) | 43.5 | 1.13 (1.92) | ||

| Unknown | 750 (16) | 45.6 | 1.26 (2.09) | ||

| Mother’s education | 0.561 | 0.451 | |||

| ≤9 year’s education | 2977 (63.3) | 43.9 | 1.13 (1.85) | ||

| >9year’s education | 986 (21) | 44.3 | 1.13 (1.90) | ||

| Unknown | 737 (15.7) | 46.1 | 1.28 (2.19) | ||

| Tooth brushing frequency | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| Twice or more per day | 1935 (41.2) | 46.7 | 1.28 (2.05) | ||

| Once per day | 1909 (40.6) | 40.5 | 0.99 (1.76) | ||

| Seldom or never | 856 (18.2) | 47.7 | 1.25 (1.92) | ||

| Use of fluoride toothpaste | 0.324 | 0.287 | |||

| Yes | 205 (5.1) | 48.3 | 1.33 (2.22) | ||

| No | 119 (3.0) | 40.3 | 0.98 (1.64) | ||

| Unknown | 3689 (91.9) | 43.8 | 1.14 (1.90) | ||

| Use of dental floss | 0.212 | 0.084 | |||

| Yes | 410 (8.7) | 47.3 | 1.32 (2.08) | ||

| No | 4290 (91.3) | 44.1 | 1.14 (1.90) | ||

| Snack frequency | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| Less than once per day | 2979 (63.4) | 41.6 | 1.06 (1.85) | ||

| Once or more per day | 1721 (36.6) | 49.2 | 1.33 (2.02) | ||

| Soft drink frequency | 0.604 | 0.361 | |||

| Less than once per day | 3781 (80.4) | 44.2 | 1.15 (1.92) | ||

| Once or more per day | 919 (19.6) | 45.2 | 1.2 (1.91) | ||

| Milk, tea, coffee with sugar | 0.048 | 0.010 | |||

| Less than once per day | 3071 (65.3) | 43.3 | 1.11 (1.90) | ||

| Once or more per day | 1629 (34.7) | 46.3 | 1.24 (1.95) | ||

| Smoke | 0.106 | 0.180 | |||

| Yes | 77 (1.6) | 35.1 | 0.87 (1.41) | ||

| No | 4623 (98.4) | 44.5 | 1.16 (1.92) | ||

| Health self-assessment | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| Good | 2918 (62.1) | 42.0 | 1.06 (1.76) | ||

| Fair or poor | 1782 (37.9) | 48.3 | 1.32 (2.13) | ||

| Tooth status self-assessment | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| Good | 1637 (34.8) | 34.2 | 0.75 (1.41) | ||

| Fair or poor | 3063 (65.2) | 49.8 | 1.37 (2.11) | ||

| Tooth injury | 0.517 | 0.672 | |||

| Yes | 727 (15.5) | 44.6 | 1.23 (2.11) | ||

| No | 2617 (55.7) | 43.7 | 1.12 (1.84) | ||

| Unknown | 1356 (28.9) | 45.6 | 1.18 (1.95) | ||

| Toothache in the previous 1 year | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| Yes | 2546 (54.2) | 52.2 | 1.48 (2.19) | ||

| No | 1613 (34.3) | 33.8 | 0.73 (1.37) | ||

| Unknown | 541 (11.5) | 38.8 | 0.91 (1.59) | ||

| Visit to dentist | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| Yes | 3112 (66.2) | 51.2 | 1.42 (2.12) | ||

| No | 1588 (33.8) | 30.9 | 0.64 (1.29) | ||

| Reason for dental visit | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| Dental treatment | 765 (56.5) | 65.9 | 2.18 (2.63) | ||

| Consult | 271 (20) | 50.9 | 1.24 (1.82) | ||

| Preventive treatment | 130 (9.6) | 36.2 | 0.97 (2.260 | ||

| Unknown | 187 (13.8) | 41.7 | 1.22 (2.00) | ||

| Dental knowledge | 0.333 | 0.752 | |||

| Score >4 | 2377 (50.6) | 43.7 | 1.14 (1.88) | ||

| Score ≤4 | 2323 (49.4) | 45.1 | 1.17 (1.95) | ||

| Dental attitude | 0.090 | 0.021 | |||

| Score =4 | 3064 (65.2) | 45.3 | 1.21 (1.97) | ||

| Score <4 | 1636 (34.8) | 42.7 | 1.05 (1.81) | ||

Table 3 shows the results of analysis using a backward logistic regression model to analyze the association between the prevalence of dental caries and related risk factors. Six risk factors were present in the final results: female sex, older age, snacks eaten once or more per day, fair or poor self-assessment dental health, toothache, and dental visit experience, and these were the most important risk factors for dental caries, with ORs ranging from 1.24 to 2.25 (P<0.01).

Table 3.

Logistic regression analysis of the risk factors related to the prevalence of dental caries.

| B | P | OR | 95% CI for OR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Gender (Female) | 0.44 | 0.000 | 1.55 | 1.37 | 1.75 |

| Age | 0.000 | ||||

| 13-year-old | 0.13 | 0.102 | 1.14 | 0.98 | 1.32 |

| 14-year-old | 0.33 | 0.000 | 1.39 | 1.20 | 1.62 |

| Snack frequency (once or more per day) | 0.21 | 0.001 | 1.24 | 1.09 | 1.40 |

| Self-assessment of teeth (fair or poor) | 0.55 | 0.000 | 1.73 | 1.52 | 1.97 |

| Toothache in the previous 1 year (yes) | 0.52 | 0.000 | 1.69 | 1.49 | 1.91 |

| Dental visit (yes) | 0.81 | 0.000 | 2.25 | 1.97 | 2.57 |

Nagelkerke R2=0.12; −2 Log likelihood=6012.902; B – regression coefficient; P – significant level; OR – odds ratios; CI – confidence interval.

Discussion

Oral health is an indispensable component of general health and is considered a determinant of good quality of life [13]. Dental caries is the most prevalent oral problem, affecting more than 2.4 billion people globally in 2010 [14]. In addition, according to the WHO report, dental caries is the fourth most expensive chronic disease to treat [15].

In most developed countries, the level of dental caries has declined over the past 20 years or so. In contrast, in many developing countries, the prevalence of dental caries has been increasing in recent years [1]. This is largely due to increased consumption of sugars and insufficient exposure to fluorides. China is the most populous and rapidly developing country in the world, but despite that, distinctions in economic status, culture, education, and diet are remarkable among different regions in China. Thus, the prevalence of oral diseases differs widely from one province to another.

Located in eastern China, Zhejiang is a relatively prosperous region compared to western and central China. By the end of 2016, the per capita GDP of Zhejiang surpassed $12 000 USD, meaning that the economic development of Zhejiang places it in the Upper-Middle Income level according to World Bank criteria. This rapid growth has changed lifestyles, and more and more cariogenic foods and drinks are consumed as a result, making sugar the highest dietary risk factor for the development of dental caries [16].

The outcome of this oral survey showed that DMFT in 12- to 14-year-old students in Zhejiang was very low (<1.2) according to the WHO dental caries severity criteria [11]. However, SiC scores (3.11) were in the moderate range (2.7–4.4), meaning that one-third of students have relatively high degree of caries experience. From the 1st Chinese National Oral Survey in 1983 to the 2nd Chinese National Oral Survey in 1995, the DMFT of Zhejiang’s 12-year-old students declined from 1.44 to 1.29 [10], and from the 2nd Chinese National Oral Survey in 1995 to the 3rd Chinese National Oral Survey in 2005, the DMFT decreased from 1.29 to 0.83 [17]. However, the results of this oral survey show an increasing trend of dental caries, from 39.3% to 40.9% prevalence and 0.83 to 0.98 DMFT, in the past decade.

Female students have relatively higher caries scores, caries prevalence, and filling rates than male students, although boys had worse oral hygiene. A possible explanation could be girls’ preference for cariogenic foods, in addition to earlier tooth eruption in girls compared to boys [18], thus exposing their teeth to a cariogenic oral environment for a longer time than boys. Moreover, females pay more attention to oral health care [19] and actively pursue dental treatment, which was reflected in a higher FT score and filling rate. A similar gender difference in dental caries was found in the USA [20] and in other provinces of China [21,22], but a report from north India showed the opposite result, which might be mostly due to the inequality of men and women in social and economic status.

Although no significant difference in DMFT score and caries prevalence was found between urban and rural students, urban students have a higher FT score and filling rate than rural students. Medical resources in China are unevenly distributed between urban and rural areas. In 2014, the number of health professionals was 5.56 per 1000 population in China, which was higher in urban areas (9.70/1000) than in rural areas (3.77/1000). More than 90% of dental hospitals and prevention institutions were built at the provincial and municipal levels [23]. Therefore, urban students have more opportunities to receive appropriate oral health education, access to dental care, and benefit from the oral health care system.

As age increases, dental caries incidence and DMFT scores clearly increase. The level of annual increase was 3% for prevalence and 0.15 for DMFT from 12- to 14-year-olds in our study population. A prospective 15-year cohort study concluded that both the incidences of new caries lesions and the rate of lesion progression were higher during adolescence than during young adulthood [24]. Clinical data show that the newly erupted teeth are most vulnerable to dental caries in the first 2–4 years, especially the first permanent molar [25], thus potentially explaining why the students’ teeth in the adolescence period have a considerably greater susceptibility to dental caries. Therefore, the importance of focusing on preventive measures in the first critical years after tooth eruption should be emphasized.

Dental injury rate in Zhejiang students was 3.4%, with a self-reported rate of 15.5% with dental injury experience. Although the prevalence is quite low compared with reports from Brazil [26] or Taiwan [27], the consequences of dental injury could be very severe, potentially causing an economic burden of treatment, and affecting the students’ mental health and quality of life [28].

Despite the risk factors, such as female sex, older age, and snacks consumption once or more per day, the logistic regression analysis showed that fair or poor self-assessment of dental health, experience of toothache, and dental visits were the most important risk factors related to dental caries, with ORs of 1.73, 1.69, and 2.25, respectively. Toothache was the most common reason for a visit to the dentist [29]. Children who visited a dentist more often had more frequent toothache and caries experience and a higher DT score [30]. Patients in China used to visit a doctor through a treatment-oriented model rather than a prevention-oriented model, and with the aim of obtaining information concerning health lifestyle or oral habits from doctors, that may explain why students who brush their teeth twice or more daily had a higher prevalence of dental caries and DMFT scores.

Dental caries in children appears to be most prevalent in medium- and high-income developing nations. Although more urbanization is taking place and cariogenic foods are much more available in those newly developed nations, the corresponding improvement in providing dental services does not keep pace [31], but at present this is not the case in Zhejiang province. Great effort in preventive oral health measures should be ready to face a predictable further increase of dental caries due to continuing social and economic development.

Primary prevention is the first line to prevent caries before it occurs. Brushing teeth twice daily with the use of fluoride toothpaste at concentrations of 1000 ppm and above is recommended for children and adolescents [32]. In our study, only 41% of students brushed their teeth twice daily, and 91.9% of participants had no idea whether the toothpaste they use contain fluoride or not. Limiting sugars to 5% of energy intake is beneficial to minimize the risk of dental caries [33]. The change in oral hygiene behavior and diet represents the strategy to modify or eliminate the causes of dental caries.

Using sealants and fluoride is another strategy to increase tooth resistance to caries [34]. In 2010, a pit and fissure sealing program was promoted as a public oral health service in schools of Hangzhou (capital city of Zhejiang), and in 2013 the program was extended to all Zhejiang regions. The program aimed to involve more than 80% of students, and the current pit and fissure sealing rate was 23.1% among urban students and 6.2% among rural students. Fluoridated water, salt, and milk were proved to be successful in public prevention. Fluoride gels, varnishes, restorative materials, and mouth rinses used by dental professionals were also effective as prevention [35].

The school-based approach to oral health data collection contributed to the high response rate obtained in this study. Strict training and calibration of the examiners and the standard of reliability set by the WHO make the results more comparable for future studies. However, the residence location identified by the Chinese census system caused proportional disparity between urban and rural students. In the self-reporting section, potential information bias such as under- or over-estimation of unhealthy habits and healthy habits may influence the results to some extent. Moreover, recall bias, especially in regards to dietary and dental experience, must be considered as well.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrated that dental caries level in 12- to 14-year-old students in Zhejiang was low, but has a tendency to increase compared with the previous oral surveys. Female students had a higher level of dental caries than male students. Dental caries prevalence annual increase was 3% with increasing age and DMFT 0.15 from 12- to 14-year-olds. Female sex, older age, increasing sugar intake, poor self-assessment of tooth health, bad dental experience, and living in a rural area with deficient oral care were factors that greatly increased dental caries risks.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful for the cooperation of all study participants and their school authorities.

Footnotes

Source of support: This study, as a part of the Fourth National Oral Health Survey in China, was conducted by the Department of Conservative Dentistry and Periodontics, Stomatology Hospital Affiliated to Zhejiang University School of Medicine. The present survey was funded by the Public Science and Technology Research Funds Project (201502002) and the 2011 China State Key Clinical Department Grants

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Petersen PE, Bourgeois D, Ogawa H, et al. The global burden of oral diseases and risks to oral health. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83(9):661–69. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Selwitz RH, Ismail AI, Pitts NB. Dental caries. Lancet. 2007;369(9555):51–59. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jackson SL, Vann WF, Jr, Kotch JB, et al. Impact of poor oral health on children’s school attendance and performance. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(10):1900–96. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.200915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krisdapong S, Prasertsom P, Rattanarangsima K, Sheiham A. Relationships between oral diseases and impacts on Thai schoolchildren’s quality of life: Evidence from a Thai national oral health survey of 12- and 15-year-olds. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2012;40(6):550–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2012.00705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Montero J, Rosel E, Barrios R, et al. Oral health-related quality of life in 6- to 12-year-old schoolchildren in Spain. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2016;26(3):220–30. doi: 10.1111/ipd.12193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kassebaum NJ, Bernabe E, Dahiya M, et al. Global burden of untreated caries: A systematic review and meta-regression. J Dent Res. 2015;94(5):650–58. doi: 10.1177/0022034515573272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Featherstone JD. The continuum of dental caries – evidence for a dynamic disease process. J Dent Res. 2004;83(Spec No C):C39–42. doi: 10.1177/154405910408301s08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Featherstone JD. The science and practice of caries prevention. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000;131(7):887–99. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2000.0307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Do LG. Distribution of caries in children: Variations between and within populations. J Dent Res. 2012;91(6):536–43. doi: 10.1177/0022034511434355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang HY, Petersen PE, Bian JY, Zhang BX. The second national survey of oral health status of children and adults in China. Int Dent J. 2002;52(4):283–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2002.tb00632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.WHO. Oral health surveys: Basic methods. 5th ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bratthall D. Introducing the Significant Caries Index together with a proposal for a new global oral health goal for 12-year-olds. Int Dent J. 2000;50(6):378–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2000.tb00572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petersen PE. Global policy for improvement of oral health in the 21st century – implications to oral health research of World Health Assembly 2007, World Health Organization. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2009;37(1):1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2008.00448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marcenes W, Kassebaum NJ, Bernabe E, et al. Global burden of oral conditions in 1990–2010: A systematic analysis. J Dent Res. 2013;92(7):592–97. doi: 10.1177/0022034513490168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petersen PE. World Health Organization global policy for improvement of oral health – World Health Assembly 2007. Int Dent J. 2008;58(3):115–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2008.tb00185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sheiham A. Dietary effects on dental diseases. Public Health Nutr. 2001;4(2B):569–91. doi: 10.1079/phn2001142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qi X. Investigation report of the third national Oral Health Survey in China. 1st ed. Beijing: People’s Medical Publishing House; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lukacs JR, Largaespada LL. Explaining sex differences in dental caries prevalence: Saliva, hormones, and “life-history” etiologies. Am J Hum Biol. 2006;18(4):540–55. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ostberg AL, Halling A, Lindblad U. Gender differences in knowledge, attitude, behavior and perceived oral health among adolescents. Acta Odontol Scand. 1999;57(4):231–36. doi: 10.1080/000163599428832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dye BA, Tan S, Smith V, et al. Trends in oral health status: United States, 1988–1994 and 1999–2004. Vital Health Stat. 2007;11(248):1–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yin W, Yang YM, Chen H, et al. Oral health status in Sichuan Province: Findings from the oral health survey of Sichuan, 2015–2016. Int J Oral Sci. 2017;9(1):10–15. doi: 10.1038/ijos.2017.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hou R, Mi Y, Xu Q, et al. Oral health survey and oral health questionnaire for high school students in Tibet, China. Head Face Med. 2014;10:17. doi: 10.1186/1746-160X-10-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu J, Zhang SS, Zheng SG, et al. Oral health status and oral health care model in China. Chin J Dent Res. 2016;19(4):207–15. doi: 10.3290/j.cjdr.a37145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mejare I, Stenlund H, Zelezny-Holmlund C. Caries incidence and lesion progression from adolescence to young adulthood: A prospective 15-year cohort study in Sweden. Caries Res. 2004;38(2):130–41. doi: 10.1159/000075937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lynch RJ. The primary and mixed dentition, post-eruptive enamel maturation and dental caries: A review. Int Dent J. 2013;63(Suppl 2):3–13. doi: 10.1111/idj.12074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paiva PC, de Paiva HN, de Oliveira Filho PM, Cortes MI. Prevalence and risk factors associated with traumatic dental injury among 12-year-old schoolchildren in Montes Claros, MG, Brazil. Cien Saude Colet. 2015;20(4):1225–33. doi: 10.1590/1413-81232015204.00752014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang B, Marcenes W, Croucher R, Hector M. Activities related to the occurrence of traumatic dental injuries in 15- to 18-year-olds. Dent Traumatol. 2009;25(1):64–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2008.00685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cortes MI, Marcenes W, Sheiham A. Impact of traumatic injuries to the permanent teeth on the oral health-related quality of life in 12–14-year-old children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2002;30(3):193–98. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2002.300305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jurgensen N, Petersen PE. Oral health and the impact of socio-behavioural factors in a cross-sectional survey of 12-year old school children in Laos. BMC Oral Health. 2009;9:29. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-9-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nomura LH, Bastos JL, Peres MA. Dental pain prevalence and association with dental caries and socioeconomic status in schoolchildren, Southern Brazil, 2002. Braz Oral Res. 2004;18(2):134–40. doi: 10.1590/s1806-83242004000200008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diehnelt DE, Kiyak HA. Socioeconomic factors that affect international caries levels. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2001;29(3):226–33. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2001.290309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walsh T, Worthington HV, Glenny AM, et al. Fluoride toothpastes of different concentrations for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):CD007868. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007868.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moynihan PJ, Kelly SA. Effect on caries of restricting sugars intake: Systematic review to inform WHO guidelines. J Dent Res. 2014;93(1):8–18. doi: 10.1177/0022034513508954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ahovuo-Saloranta A, Forss H, Hiiri A, et al. Pit and fissure sealants versus fluoride varnishes for preventing dental decay in the permanent teeth of children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(1):CD003067. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003067.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Petersen PE, Ogawa H. Prevention of dental caries through the use of fluoride – the WHO approach. Community Dent Health. 2016;33(2):66–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]