Abstract

Introduction:

The purpose of this study was to compare pharmacists' level of training and/or experience in psychiatric pharmacy to (1) their self-perceived preparedness to provide pharmacotherapy services to individuals with psychiatric disorders and (2) barriers to providing pharmacotherapy services to individuals with psychiatric disorders.

Methods:

This study used data from an Internet-based questionnaire. Respondents were divided into 2 groups: group A completed the Arizona Pharmacy Association's Psychiatric Certificate Program, and/or was board certified in psychiatric pharmacy, and/or was a member of the College of Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacists, and/or had completed a psychiatric pharmacy residency; group B had no specialized training and/or experience in psychiatric pharmacy. A Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the scaled responses for each group.

Results:

Compared with pharmacists without training and/or experience in psychiatry (N = 235), respondents with specialized training and/or experience in psychiatric pharmacy (N = 38) reported more frequent interactions with patients with psychiatric disorders and provided more counseling and drug information, monitoring for adverse drug reactions, screening for treatment issues, and both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatment recommendations (P < .05). Pharmacists trained in psychiatry reported being more prepared to provide all pharmacotherapy services (P < .003), except in addressing nonadherence, utilizing online resources, and providing pharmacotherapy services to patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. They reported fewer barriers to providing pharmacotherapy services (P < .005), except for time to provide services, having a private consultation area, and reimbursement for patient care activities.

Discussion:

This study found that responding pharmacists without psychiatric training/experience may need additional education and training after graduation and that they perceive more barriers in providing services to the population with psychiatric disorders.

Keywords: pharmacists, questionnaires, mental disorders, attitude of health personnel, health knowledge, attitudes, needs assessment

Introduction

The College of Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacists (CPNP) represents more than 1000 pharmacists who have been trained or employed to provide services to patients with psychiatric and neurologic disorders.1 As of 2016, through the Board of Pharmacy Specialties, 819 pharmacists are board certified in psychiatric pharmacy (BCPP) in the United States.2 In 2015, the US Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that 295 620 pharmacists are employed in the United States and, of those, approximately 6000 pharmacists are employed in Arizona.3 Because of the need for further clinical training in psychiatry, the Arizona Pharmacy Association (AzPA) developed a Psychiatric Certificate Program (AzPA-PCP) in 2013 that is practice based for pharmacists in all settings with the goal of enhancing pharmacists' clinical knowledge that can be applied directly to the patients they serve.4 The AzPA-PCP was approved for 25.5 contact hours (or 2.55 continuing education units) and involves a self-study and live training seminar that includes didactic presentations by faculty who are CPNP members and are BCPP as well as interactive case presentations so participants can practice comprehensive medication therapy management skills for psychiatric disorders.

The purpose of this study was to compare pharmacists' level of training and/or experience in psychiatric pharmacy to (1) their self-perceived preparedness to provide pharmacotherapy services to individuals with psychiatric disorders and (2) barriers to providing pharmacotherapy services to individuals with psychiatric disorders.

Methods

Design

This study used data obtained from a cross-sectional Internet-based questionnaire and was deemed exempt by the University of Arizona Institutional Review Board.

Subjects

Study participants were recruited using an e-mail database of approximately 6000 licensed pharmacists in Arizona that included both members and nonmembers of AzPA.

Treatment

The primary independent variable was a pharmacist's level of training and/or experience in psychiatric pharmacy. Participants were divided into 2 groups based on responses to key demographic questions in the questionnaire: Group A consisted of pharmacists who had specialized training and/or experience in psychiatric pharmacy (ie, they were BCPP, were a CPNP member, had completed a psychiatric pharmacy residency program, or had completed the AzPA-PCP); group B consisted of pharmacists without specialized training and/or experience in psychiatric pharmacy.

Measures

The questionnaire comprised 40 items divided into 3 sections, and was based on the program goals and learning objectives of the AzPA-PCP and 2 similar studies that assessed pharmacists' attitudes toward patients with mental health conditions and barriers to providing services to those patients with mental health conditions.4-6 Section 1 consisted of 15 questions asking respondents to rate their agreement with statements about their self-perceived preparedness to provide pharmacotherapy services to patients with psychiatric disorders. Section 2 had 10 questions asking respondents to rate their agreement with statements about the presence of perceived barriers to providing pharmacotherapy services to individuals with psychiatric disorders as well as 1 question asking respondents to write in perceived barriers not listed as answer options. Section 3 contained 14 demographic questions.

Data Collection

Pharmacists belonging to the AzPA pharmacist listserv were emailed a cover letter explaining the project as well as a link to the online questionnaire. The online questionnaire utilized SurveyMonkey® software (San Mateo, CA). Before being allowed to enter the questionnaire participants were asked to provide informed consent; upon giving their consent, participants were forwarded to the questionnaire. The cover letter was e-mailed to the same listserv a total of 3 times, and each distribution period was separated by 2 weeks.

Data Analysis

Descriptive and demographic variables were analyzed by calculating means and standard deviations for continuous variables then using a Student t test to compare groups A and B. A Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the groups for self-perceived barriers to provide pharmacotherapy services. Categorical variables were analyzed by calculating frequencies and percentages then using a χ2 test to compare groups. The a priori alpha level was set at 0.05. A Bonferroni alpha correction was used for the primary intervention to adjust for multiple comparisons.

Results

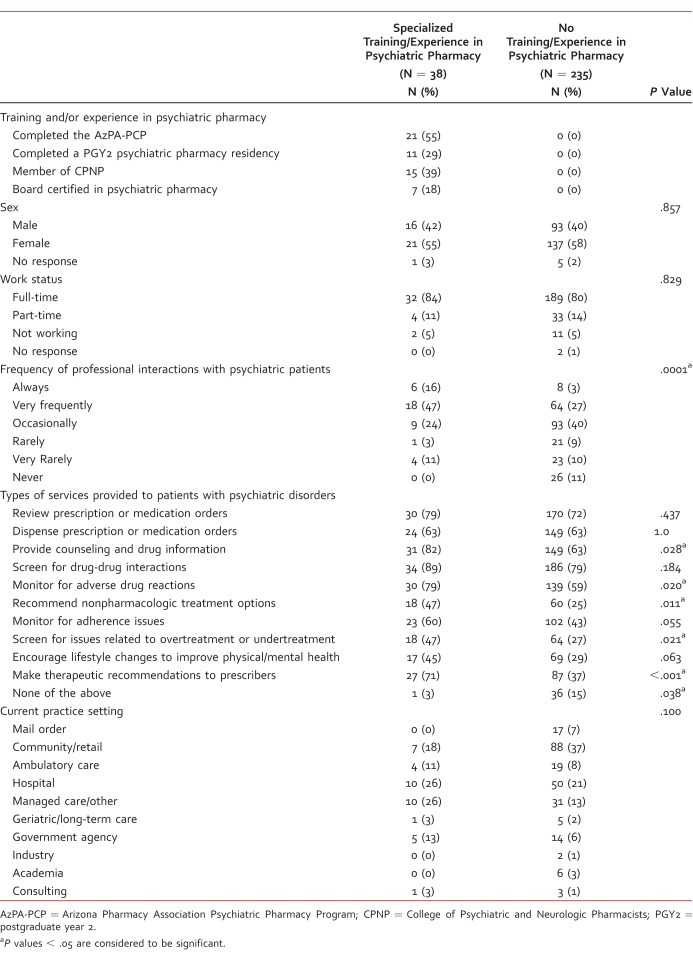

A total of 273 Arizona pharmacists completed the online questionnaire (Table 1). Group A consisted of 38 pharmacists with specialized training/experience in psychiatric pharmacy: 15 were members of CPNP, 11 had completed a psychiatry pharmacy residency, 7 were BCPP, and 21 had completed the AzPA-PCP. Group B consisted of 235 pharmacists who reported no training/experience in psychiatric pharmacy. There were no differences between groups in sex, work status, and current practice setting.

TABLE 1.

Respondent demographics (N = 273)

Pharmacists with no specialized training and/or experience in psychiatric pharmacy more often reported providing no services to patients with psychiatric disorders (P = .038). Compared with the pharmacists with no training and/or experience, pharmacists with specialized training and/or experience in psychiatric pharmacy reported more of the following: professional interactions with patients with psychiatric disorders (P = .0001), providing counseling and drug information (P = .028), monitoring for adverse drug reactions (P = .020), recommending nonpharmacologic treatment options (P = .011), screening for issues related to overtreatment or undertreatment (P = .021), and making therapeutic recommendations to prescribers (P < .001).

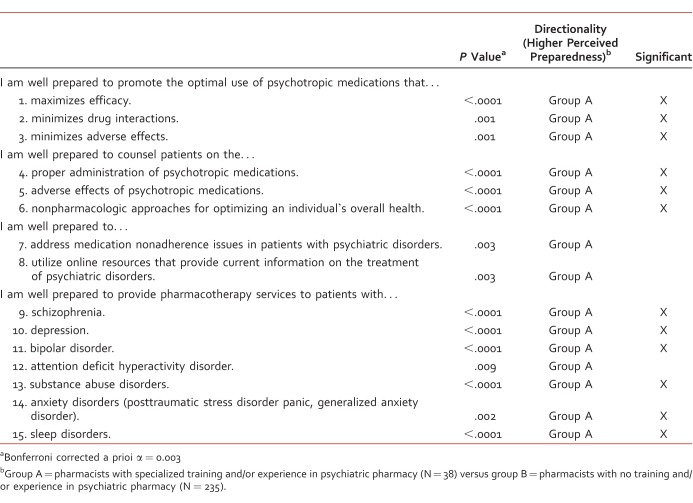

Pharmacists with specialized training/experience reported being more prepared to provide all pharmacotherapy services (Table 2) with the exception of addressing nonadherence (P = .003), utilizing online resources (P = .003), and providing pharmacotherapy services to patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (P = .009).

TABLE 2.

Respondent self-reported preparedness to provide psychiatric pharmacotherapy services

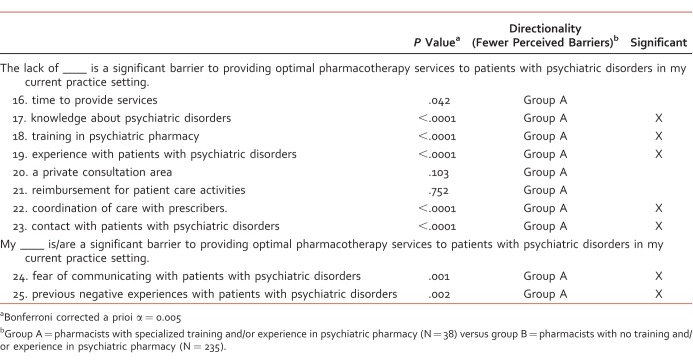

Pharmacists without specialized training/experience perceived more barriers to providing pharmacotherapy services (Table 3). These barriers included a lack of knowledge about psychiatric disorders (P < .0001), lack of training in psychiatric pharmacy (P < .0001), lack of experience with patients with psychiatric disorders (P < .0001), lack of coordination of care with prescribers (P < .0001), lack of contact with patients with psychiatric disorders (P < .0001), fear of communicating with patients with psychiatric disorders (P = .001), and previous negative experiences with patients with psychiatric disorders (P = .002). There was no difference between the 2 groups in barriers pertaining to time to provide services (P = .042), having a private consultation area (P = .103), and reimbursement for patient care activities (P = .752). There were 10 write-in responses from participants, all of which were closely related to or a rewording of the options provided.

Table 3.

Barriers to providing pharmacotherapy services

Discussion

Based on a review of published literature, this is the first study to compare a pharmacist's level of training and/or experience in psychiatric pharmacy to his or her self-perceived preparedness to provide pharmacotherapy services and barriers to providing these services to individuals with psychiatric disorders. Previous studies have focused on the assessment of pharmacist's attitudes toward patients with mental illness, their confidence in providing pharmaceutical care to patients with mental illness, and their perceived barriers to providing pharmaceutical care to patients with mental illness.7,8 A common theme in past research is that pharmacists are generally less comfortable providing services to patients with mental illness compared with patients with nonpsychiatric illnesses despite having generally positive attitudes toward patients with mental illness.

The CPNP Foundation published a guide for patients and families on what types of services they should expect from a community pharmacist.9 The guide lists 10 examples of services that should be provided and encourages patients to develop a relationship with their pharmacist to receive the best care and to avoid adverse effects from medications. Based on the findings of this study, community pharmacists may need education in how to be prepared and involved with patients with psychiatric disorders and their families. In addition, improving medical adherence in patients with a psychiatric disorder may require training to improve outcomes that affect their quality of life, morbidity, and mortality.10

The results of this study suggest that pharmacists with specialized training and/or experience in psychiatric pharmacy have more frequent professional interactions with patients with psychiatric disorders, provide more pharmacotherapy services to patients with psychiatric disorders, perceive themselves as being more prepared to provide pharmacotherapy services to patients with psychiatric disorders, and have fewer barriers to providing services compared with their counterparts with less training and experience. Ultimately, this study supports the use of additional training or certificate continuing education programs such as AzPA-PCP that increase the knowledge in psychiatric disorders and pharmacotherapy in order to better prepare pharmacists to provide services in their practice setting.

This study had several key limitations. Of the 273 total participants, 14% (N = 38) were classified as having specialized training and/or experience in psychiatric pharmacy. Of these, 21 pharmacists (55%) had completed the AzPA-PCP, which may reflect higher rates of psychiatric pharmacy training in Arizona compared with other states. In addition, pharmacists could belong to more than 1 group at a time (eg, a pharmacist could be a CPNP member and have completed the AzPA-PCP), so the individual effect of each type of training/experience on self-perceived preparedness and barriers was not evaluated. Pharmacists who completed only postgraduate year 1 residency training were not included in the data analysis; thus, it is unclear how much, and in what ways, postgraduate year 1 residency training may contribute to differences in self-perceived preparedness and barriers to providing pharmacotherapy services to patients with psychiatric disorders. Since there was no assessment of pharmacists' actual knowledge or abilities, there is no way to validate their self-perceived preparedness. The results of this study cannot be generalized to other US pharmacists since the participants practiced exclusively in the state of Arizona.

Conclusions

This study found that pharmacists with specialized training and/or experience in psychiatric pharmacy reported being more prepared to provide pharmacotherapy services to patients with psychiatric disorders. The pharmacists also reported fewer barriers to providing these services, particularly barriers pertaining to knowledge of psychiatric disorders, training in psychiatric pharmacy, and a lack of experience and contact with patients with psychiatric disorders. The study found several barriers that explain why pharmacists without specialized training and/or experience may not be involved with patients with psychiatric disorders. Barriers to providing care included lack of training in mental health, lack of experience with patients with psychiatric disorders, fear of communicating with patients with psychiatric disorders, past negative experiences with patients with psychiatric disorders, and lack of knowledge about the patient and his or her treatment. Colleges of pharmacy should reassess their course work and clinical training in mental health to improve exposure to patients with psychiatric disorders. In addition, continuing education conferences, certificate programs, and residency training in psychiatry should be promoted for postgraduate pharmacists since only a small number employed in the United States have the experience or confidence to provide pharmacotherapy services for patients with psychiatric disorders.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Martha Fankhauser for assistance with the methodology of the research project and manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors do not have personal or financial interests to disclose. This study was presented in abstract form and as a poster at the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists Midyear Clinical Meeting, Anaheim, California, on December 16, 2014.

References

- 1. College of Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacists [Internet]. Lincoln (NE): The College; c2003-2016 [cited 2016. Jun 20]. CPNP membership profile. Available from: https://cpnp.org/_docs/about/membership_profile.pdf

- 2. Board of Pharmacy Specialties [Internet]. Washington: The Board; c.2015 [cited 2016. Jun 20]. Certification stats by location. Available from: http://www.bpsweb.org/find-a-board-certified-pharmacist/.

- 3. Bureau of Labor Statistics [Internet]. Washington: The Bureau [cited 2016. Jun 20]. Healthcare: Pharmacists. Available from: http://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes291051.htm

- 4. Arizona Pharmacy Association [Internet]. Tempe: The Association [cited 2016. Jun 20]. Psychiatric Certificate Program. Available from: http://www.azpharmacy.org/?page=Psychiatric

- 5. Phokeo V, Sproule B, Raman-Wilms L. . Community pharmacists' attitudes toward and professional interactions with users of psychiatric medication. Psychiatric Serv. 2004; 55 12: 1434- 6. DOI: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.12.1434. PubMed PMID: 15572574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Scheerder G, De Coster I, Van Audenhove C. . Pharmacists' role in depression care: a survey of attitudes, current practices, and barriers. Psychiatric Serv. 2008; 59 10: 1155- 60. DOI: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.10.1155. PubMed PMID: 18832501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rickles NM, Dube GL, McCarter A, Olshan JS. . Relationship between attitudes toward mental illness and provision of pharmacy services. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2010; 50 6: 704- 13. DOI: 10.1331/JAPhA.2010.09042. PubMed PMID: 21071314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cates ME, Burton AR, Woolley TW. . Attitudes of pharmacists toward mental illness and providing pharmaceutical care to the mentally ill. Ann Pharmacother. 2005; 39 9: 1450- 5. DOI: 10.1345/aph.1G009. PubMed PMID: 15972325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. CPNP Foundation [Internet]. Lincoln (NE): The Foundation [cited 20 June 2016]. What you should expect from your pharmacist. Available from: https://cpnpf.org/_docs/foundation/2015/guidelines-what-you-should-expect.pdf

- 10. Lee KC. . Improving medication adherence in patients with severe mental illness. Pharmacy Today [Internet]. 2013. [cited 2016 Jun 20]; 19 6: 69- 80. Available from: http://elearning.pharmacist.com/Portal/Files/LearningProducts/8e1241c42b5047829a1cdc44598e6ebe/assets/0613_PT_80_FINAL.pdf [Google Scholar]