Abstract

The use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) is gaining popularity in the Western world. Among the general public, CAM is often perceived to be associated with less stigma, fewer adverse effects, and may be more affordable. A number of patients utilize CAM for the treatment of depression; however, as there is limited scientific evidence, the safety profile of these supplements are largely unknown. In this case, a 42-year-old man developed hypomania approximately 1 week after S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe) and 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP) therapy was initiated for depression. The combination of SAMe and 5-HTP can potentially induce hypomanic episodes.

Keywords: S-adenosylmethionine, 5-hydroxytryptophan, mood disorders, depression, complementary therapies

Background

The use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) is gaining popularity in the Western world.1 Patients may regard prescription antidepressants with skepticism due to the black box warning associated with an increased risk of treatment-emergent suicide, which is not a warning within CAM labeling.2 Preference may further align with CAM therapies because of the belief that “natural is better.”1 Among the general public, CAM may be perceived to be associated with less stigma, fewer adverse effects, and lower cost.

The use of CAM for depression by patients with mental illness is estimated to range between 16% and 44%.1 Studies have shown that CAM may have comparable efficacy in relation to traditional pharmacologic therapy. However, these studies have scarce scientific support due to limitations in study design and methodology. Often these studies have a small sample size, heterogeneity of study design, and methodological issues with randomization and compliance.1,3-6 According to the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2016 guidelines,1 it is recognized that pharmacologic and/or psychological treatments are preferred over CAM therapies due to a higher level of evidence with a higher standard of quality.

Despite this disclaimer, CANMAT guidelines recommend CAM, such as exercise and St John's wort, as first-line monotherapy for the treatment of mild to moderate major depressive disorder. Exercise, light therapy, yoga, omega-3, and S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe) are recommended as second-line adjunctive treatment for major depressive disorder depending on severity of illness.1 Mental Health America is a nonprofit organization focused on improving mental health treatment. Mental Health America published a thorough review of CAM, including data from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine as well as 10 different textbooks on CAM. In this review,7 SAMe was recommended as first-line CAM treatment for mild, moderate, or severe depression, and 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP) was not recommended due to insufficient data. Another review8 recommends avoiding CAM as first-line treatment when patients are an acute danger to themselves or others or are unable to care for themselves or dependents in their care.

The use of SAMe and 5-HTP is the focus in this case report. SAMe is a naturally occurring derivative of L-methionine and acts as a methyl donor in the production of neurotransmitters, increasing brain levels of serotonin and epinephrine.9 5-HTP is a precursor to serotonin that can be extracted from the African plant known as Griffonia simplicifolia.10 Typical dosing of each supplement is as follows: SAMe 400 to 1600 mg daily and 5-HTP 150 to 800 mg daily for depression.11,12 Potential adverse effects associated with these 2 over-the-counter (OTC) supplements include induction of mania, serotonin syndrome, gastrointestinal distress, agitation, anxiety, insomnia, sexual dysfunction, tremor, and headache.5,11-13

Case

This case report describes a 42-year-old man who was admitted for unspecified mood disorder. The patient had no known medical or psychiatric history. He denied substance use, which was confirmed with a negative urine toxicology screen. His spouse brought him to the comprehensive psychiatric emergency program with a chief complaint of “nervous breakdown.” Upon assessment, tangential and racing thoughts were present with expansive and pressured speech accompanied with an anxious affect. The patient reported having a difficult time the past 2 weeks because of recent unemployment, which was stressful because he was the main caregiver of the family. His spouse described him over the past week as being hyperactive, impulsive, loquacious, and irrational with side-to-side ocular movements. Three days prior to admission, the patient was in the living room, naked, screaming, “I'm great,” and pounding his chest. He had not slept for 2 days prior to admission.

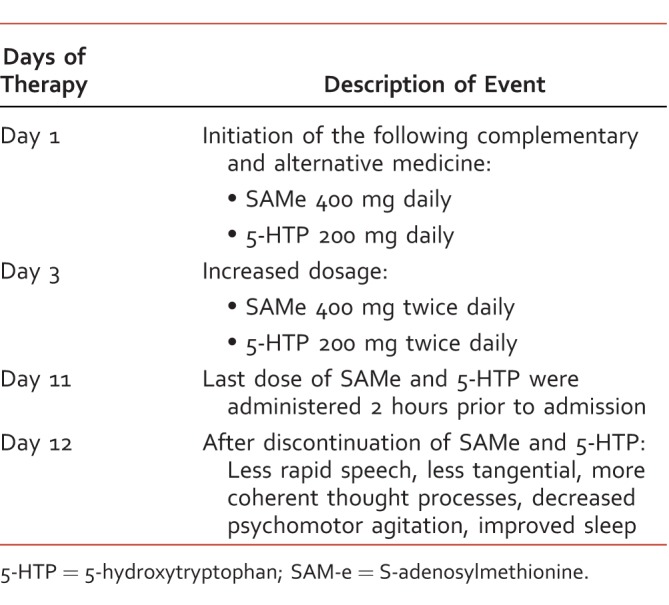

The patient's mother and father visited and agreed with the spouse, stating that the patient's behavior was erratic and believed it was due to the OTC supplements he had been taking. The parents described the patient's baseline behavior as calm and well mannered. The patient developed symptoms consistent with hypomania approximately 1 week after initiating SAMe and 5-HTP therapy for depression (the patient reported initiating SAMe and 5-HTP therapy 10 days prior to admission). The patient was on a regimen of 200 mg of 5-HTP and 400 mg of SAMe once daily for 3 days, which then increased to twice daily administration (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Timeline of over-the-counter administration and discontinuation

The OTC supplements were discontinued by the hospital team upon admission, and the patient was not started on new medications. The first night of hospitalization, the patient slept for 30 minutes. On the morning of the second day of hospitalization, he was seen with the treatment team for the first time, presenting as energetic with an anxious affect. He was displaying flight of ideas and had pressured and tangential speech. That evening, the subject slept a total of 7 hours. The patient's sleep time increased from an average of 3 hours per night prior to admission. That same day, the patient continued presenting with rapid speech, but his thoughts were more coherent and logical. The patient also reported being “more focused and sharp.” The third day of hospitalization, the patient continued to be slightly anxious and tangential; however, he had less racing thoughts and pressured speech. The patient was provided with psychotherapy options to help with depressive symptoms and discharged that day with improved symptoms.

Discussion

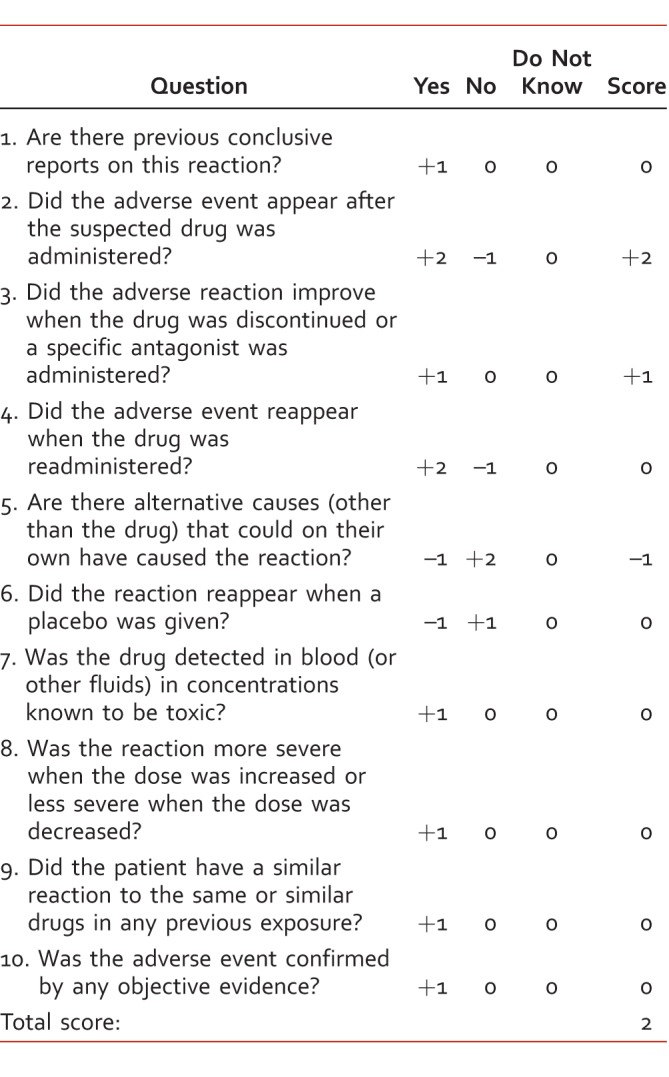

Based upon the clinical presentation, the subject meets the Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition,14 criteria for a hypomanic event. He had a distinct period of increased activity and energy lasting at least 4 consecutive days and which were present most of the day. During this period of increased energy, the patient was more talkative than usual, saw an increase in goal-directed activity, and experienced pressured speech, flight of ideas, and decreased need for sleep.14 The disturbance in mood and change in functioning was observable by others, in this case, by the patient's family. Upon review of the medication reconciliation, the patient did not receive any new medications that could have induced the hypomanic event. Per the Naranjo adverse drug reaction probability scale,15 the combination of SAMe and 5-HTP was a possible cause of the hypomanic episode (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Naranjo adverse drug reaction probability scale15

Undiagnosed bipolar disorder, substance-induced hypomania, and treatment-emergent affective switch are all considered in the differential. A definitive diagnosis is difficult to determine with 1 short hospitalization as the patient had never been formally evaluated by a health care professional prior to this episode.

Concerning treatment-emergent affective switches, it is currently a controversial area whether antidepressants should be used in patients with bipolar disorder. Studies16-18 have shown antidepressants do not accelerate time to recovery nor have higher recovery rates compared with mood stabilizers alone. However, it is a known risk that antidepressants can cause a switch into a manic or hypomanic state.16-20 A meta-analysis by Ghaemi et al17 showed that long-term antidepressant treatment had a 72% greater risk for inducing a manic episode compared with a mood stabilizer alone. The patient's symptoms preceding CAM onset were mainly depressive, and the affective switch was induced after initiation. Also note that treatment-emergent affective switches are not instantaneous and may take weeks of treatment before an antidepressant-induced switch occurs.16,20 The combination and possible synergistic effect of the OTC medications taken concomitantly may have increased the risk of a hypomanic episode. There has been evidence of SAMe inducing a switch (euphoria, hypomania, or mania) at a rate of 33% in 9 patients. Six of the affective switches were recognized to occur after intravenous and 5 after oral SAMe administration.9 Additionally, there has been at least 1 documented case21 of 5-HTP inducing a manic event within 1 week's time; however, the patient had been on multiple contributing agents including phenelzine and as-needed prednisone.

Pharmacokinetically, the half-lives of SAMe and 5-HTP are relatively short, ranging from 80 to 100 minutes and 2 to 6 hours, respectively.11,12 Therefore, discontinuation of both supplements resulted in symptom resolution quickly.

Last, due to these CAM being non–FDA-approved, it is impossible to verify the exact quantity of active compound present in each product consumed by the patient.13 SAMe is unstable at room temperature, making it impossible to know precisely how much SAMe was active in each capsule.12 Therefore, replication of this event would be difficult because of each supplement conceivably containing a different amount of active ingredient.

Conclusion

The use of SAMe and 5-HTP carries the possible risk of inducing symptoms of mania. This risk may be increased when both products are used together because both are thought to increase levels of serotonin in the brain. Patients with bipolar rather than unipolar depression appear to be at significantly higher risk of switch. This case emphasizes the importance of involving health care providers in baseline assessment and the ongoing monitoring of CAM for mood disorders. Pharmacists should be prepared to discuss appropriate warnings and precautions with patients who seek guidance prior to initiating therapy.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have nothing to disclose concerning possible financial or personal relationships with commercial entities (or their competitors) that may be referenced in this research project.

References

- 1. Ravindran AV, Balneaves LG, Faulkner G, Ortiz A, McIntosh D, Morehouse RL, et al. . Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2016 clinical guidelines for the management of adults with major depressive disorder. Can J Psychiatry. 2016; 61 9: 576- 87. DOI: 10.1177/0706743716660290. PubMed PMID: 27486153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Carpenter DJ. . St. John's wort and s-adenosyl methionine as “natural” alternatives to conventional antidepressants in the era of the suicidality boxed warning: what is the evidence for clinically relevant benefit? Altern Med Rev. 2011; 16 1: 17- 39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sarris J. . Clinical depression: an evidence-based integrative complementary medicine treatment model. Altern Ther Health Med. 2011; 17 4: 26- 37. PubMed PMID: 22314631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moss AS, Monti DA, Amsterdam JD, Newberg AB. . Complementary and alternative medicine therapies in mood disorders. Expert Rev Neurother. 2011; 11 7: 1049- 56. DOI: 10.1586/ern.11.77. PubMed PMID: 21721920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lavretsky H. . Complementary and alternative medicine use for treatment and prevention of late-life mood and cognitive disorders. Aging Heal. 2009; 5 1: 61- 78. DOI: 10.2217/1745509X.5.1.61. PubMed PMID: 19956796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Werneke U. . Complementary medicines in mental health. Evid Based Ment Health. 2009; 12 1: 1- 4. DOI: 10.1136/ebmh.12.1.1. PubMed PMID: 19176764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Complementary & alternative medicine for mental health. Mental Health America [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2017 Jan 2]. Available from: http://www.mentalhealthamerica.net/mentalhealthandcam

- 8. Bongiomo PB. . Complementary and alternative medical treatment for depression. : Licinio J, Wong M-L, . Biology of depression. Weinheim (Germany): Verlag BmbH & Co KGaA; 2005. p 993- 1019. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Murphy BL, Babb SM, Ravichandran C, Cohen BM. . Oral SAMe in persistent treatment-refractory bipolar depression: a double-blind, randomized clinical trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014; 34 3: 413- 6. DOI: 10.1097/JCP.0000000000000064. PubMed PMID: 24699040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Young SN. . Are SAMe and 5-HTP safe and effective treatments for depression? J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2003; 28 6: 471 PubMed PMID: 14631459. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database. 5-HTP monograph [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2016 Oct 20]. Available from: http://naturalmedicines-therapeuticresearch-com.lb-proxy13.touro.edu

- 12. Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database. SAMe monograph [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2016 Oct 20]. Available from: http://naturalmedicines-therapeuticresearch-com.lb-proxy13.touro.edu

- 13. Popper CW. . Mood disorders in youth: exercise, light therapy, and pharmacologic complementary and integrative approaches. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2013; 22 3: 403- 41. DOI: 10.1016/j.chc.2013.05.001. PubMed PMID: 23806312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington (VA): American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, Sandor P, Ruiz I, Roberts EA, et al. . A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981; 30 2: 239- 45. DOI: 10.1038/clpt.1981.154. PubMed PMID: 7249508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sachs GS, Nierenberg AA, Calabrese JR, Marangell LB, Wisniewski SR, Gyulai L, et al. . Effectiveness of adjunctive antidepressant treatment for bipolar depression. N Engl J Med. 2007; 356 17: 1711- 22. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa064135. PubMed PMID: 17392295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ghaemi SN, Wingo AP, Filkowski MA, Baldessarini RJ. . Long-term antidepressant treatment in bipolar disorder: meta-analyses of benefits and risks. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008; 118 5: 347- 56. DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01257.x. PubMed PMID: 18727689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Goldberg JF, Perlis RH, Ghaemi SN, Calabrese JR, Bowden CL, Wisniewski S, et al. . Adjunctive antidepressant use and symptomatic recovery among bipolar depressed patients with concomitant manic symptoms: findings from the STEP-BD. Am J Psychiatry. 2007; 164 9: 1348- 55. DOI: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.05122032. PubMed PMID: 17728419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Altshuler LL, Post RM, Leverich GS, Mikalauskas K, Rosoff A, Ackerman L. . Antidepressant-induced mania and cycle acceleration: a controversy revisited. Am J Psychiatry. 1995; 152 8: 1130- 8. DOI: 10.1176/ajp.152.8.1130. PubMed PMID: 7625459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Post RM, Altshuler LL, Frye MA, Suppes T, Rush AJ, Keck PE, et al. . Rate of switch in bipolar patients prospectively treated with second-generation antidepressants as augmentation to mood stabilizers. Bipolar Disord. 2001; 3 5: 259- 65. DOI: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2001.30505.x. PubMed PMID: 11912569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pardo JV. . Mania following addition of hydroxytryptophan to monoamine oxidase inhibitor. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2012; 34 1: 102.e13- 4. DOI: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2011.08.014. PubMed PMID: 21963353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]