Abstract

Suicide rates are high in high-income countries like Canada and the United States, where 10 to 12 people per 100 000 commit suicide every year. In the United States, in 2011 there were 73.3 emergency room visits per 100 000 people for suicide attempts with prescription drugs. The latter were also involved in 13% of completed suicides between 1999 and 2013. In most cases, these drugs were distributed by members of our profession who could not predict this outcome. This led us to create an initiative to teach pharmacy students how to prevent suicide. A literature review and online search were performed to find documentation about pharmacists' commitment to the cause, but very little information exists. Thus, a training session was developed for third-year pharmacy students that includes basic statistics, arguments for involving pharmacists in suicide prevention, role-playing, tools to evaluate suicide risk, thoughtful verbatims of interview techniques, and case studies. It is delivered during the mental health theme of the psychiatry course. In 5 years, around 1150 students have participated in the course, of whom approximately 950 are now practicing pharmacists. This intervention may have prevented some suicides, although the impact is impossible to measure. The objective of this paper is to describe the creative process of designing a suicide prevention training session for pharmacy students, while inspiring a mental health sensitive readership to this noble cause. This article does not provide guidelines on how to replicate this initiative, nor does this article replace proper training on suicide prevention.

Keywords: suicide, prevention, pharmacist, students, education

Introduction

Suicide rates are high in high-income countries like Canada and the United States, where 10 to 12 people per 100 000 commit suicide every year.1 In the United States, in 2011 there were 73.3 emergency room visits per 100 000 people for suicide attempts with prescription drugs.2 These drugs were also involved in 13% of completed suicides between 1999 and 2013.3 In most of these cases, these drugs were distributed by members of our profession who unfortunately could not predict this fatal outcome.

Fortunately, suicide rates have fallen by 33% in the last 18 years in the province of Quebec, Canada, but the tragedy is still ongoing, and several national mental health policies have been proposed to stop it.4 The proposed health policies include 4 objectives/strategies: First, expand the general population's knowledge of mental health. Second, create sentinels of distress at key social gathering points, like schools, workplaces, and in the health system. Third, optimize the management of depression and substance abuse disorders. And finally, optimize the follow-up of people at risk of suicide. The development of a course to train pharmacy students in the detection and prevention of suicide is inspired by the recommendation to create sentinels of distress. As future pharmacists, they will be the guardians of a preferred means of suicide. Similarly to other suicide prevention program initiators, like Patrick Tharp (http://www.pharmacistspreventingsuicides.com), we believe that training pharmacy students in suicide prevention techniques will contribute to lowering the rate of suicide by prescription drugs.

The objective of this paper is to describe the creative process of designing a suicide prevention training session for pharmacy students, while inspiring a mental health–sensitive readership to this noble cause. This does not provide guidelines on how to replicate this initiative, nor does this article replace proper training on suicide prevention.

Background

A literature review and online search was done to find documentation about pharmacists' commitment to suicide prevention in the English- and French-speaking world. The databases searched include Google, EMbase, and PubMed, with obvious keywords, such as suicide and pharmacist. Very little published information exists about clinical actions taken by pharmacists to prevent suicide, apart from pharmacologic recommendations.

Of mention is the group Pharmacists Preventing Suicide, in Missouri (http://www.pharmacistspreventingsuicides.com). This organization is a group of pharmacists dedicated to disseminating basic suicide prevention training to schools of pharmacy and other organizations for more than 10 years. The group even proposed a bill in the state that would require all state pharmacists to receive and maintain training in suicide prevention.

Another initiative of interest is led by David Garner in Nova Scotia (Canada). He and other clinicians are raising awareness and creating networks to support people with mental illness (http://www.morethanmeds.com). Their tool, the Navigator, is a national list of local resources in mental health that anyone, including pharmacists, can use to refer their patients to appropriate services.

Lavigne et al5 report on a nationwide protocol to provide training on suicide prevention techniques to all Veterans Affairs personnel in contact with patients. At the end of a 1-hour course including video and practical exercises, the confidence of pharmacists and pharmacy personnel to intervene in cases of suicidal patients was on par with that in other groups.

In Hamilton, Canada, a pharmacy student spoke out in a peer-reviewed paper about her experience with a suicidal patient; the student was the first that patient confided to. She explains how collaboration with the physician and compassion with the patient resulted in a more intensive follow-up and proper management of his suffering.6

These interesting but sporadic initiatives give new light to a seminal paper from 1972 by Gibson and Lott. Thirty-three years ago they proposed that suicide prevention training be a skill taught in all schools of pharmacy.7 Their innovative ideas were: to report suicide attempts to all health professionals caring for a patient in order to create a network of sentinels, that dispensing large quantities of dangerous drugs be proscribed, that pharmacists be aware of local resources to help people with suicidal ideation, that patients be encouraged to frequent only one pharmacy, and that pharmacists should educate the public both on the safe disposition of drugs and the recognition of drugs used to commit suicide. They also proposed that pharmacists should be able to detect signs of distress that are associated with suicide, such as: openly verbalized ideas of self-harm, ongoing depression, loss of a close one by suicide, and despair. Unfortunately, the citation map of this article shows that the idea has not been picked up and generalized.

This literature review suggests that, although currently underused, pharmacists represent a potential resource for suicide prevention with appropriate training and education. A training program to fulfill this objective is described here.

Method

Setting Goals for a Suicide Prevention Training Program

We received suicide prevention training provided by renowned organizations Suicide Action Montreal and the Association québécoise de prévention du suicide (AQPS).8 This helped us set goals and required learning activities for our educational program for pharmacy students. We chose to focus on 2 of the nationally proposed strategies for preventing suicides: optimize the management of depression, and create sentinels of mental distress.4

The first strategy is aimed at people with depression, who are both the largest and most at-risk population for suicide.9 Unfortunately, primary nonadherence to antidepressants is very difficult to manage, but nonpersistence can be caught easily with simple alarms in pharmacy software. The role pharmacists could make in this national strategy is to follow up 30 days afterwards all new antidepressant dispensation, because 43% of patients will not come back for the first refill, and suicidal thoughts and disinhibition have been reported in the first months of treatment.10 At this time, the pharmacist could manage problems with the antidepressant, and file for reimbursement if appropriate.

The second strategy is aimed at people who verbalize mental distress or suicide ideation. The listener should be able to respond in the appropriate, soothing, and compassionate way. Pharmacists have these communication abilities. The structure of an ideal interview includes assessing suicide planning, risk factors, and protective factors, and results in making a safety plan and follow-up. Together, these interventions have the potential to reduce incidences of untreated depression and lower suicide rates.

Creating the Educational Strategy

The training session was aimed at third-year pharmacy students during the opening session of a 45-hour psychiatry course in the Faculty of Pharmacy at the Université de Montréal. The learning objectives were: (1) to confront one's values and emotions about the phenomenon of suicide, (2) to understand the psychologic and existential dynamics of suicide, (3) to evaluate the risk of suicide for an individual, (4) to intervene appropriately with people having suicidal ideations, and (5) to be aware of local resources dedicated to mental health.

To meet these learning objectives, a 4-part, 90-minute training session was developed. First, students learned about basic statistics on suicide and arguments for involving pharmacists in suicide prevention. Second, learners were put in pairs for role-playing in two scenarios inspired by real-life cases that the authors had managed in the past. Third, students were provided with tools to evaluate suicide risk and thoughtful verbatims of interview techniques. Finally, case studies were presented and discussed to integrate this new knowledge.

The material used for course planning came in part from public statements and documents of the AQPS, because its message is convincing and easy to understand. However, to attain the specific goals of the course, much of the content was created and implemented based on the authors' experience. Interview techniques for mentally distressed patients are not common knowledge, so case-based role-playing activity was created.

Results

Teaching Experiences

Before teaching the intervention goals to pharmacy students, their reception and potential implementation in community pharmacies was surveyed. We visited 30 community pharmacists treating severely ill patients from a local psychiatric hospital, within a 20-km radius, where the pilot training sessions were provided and written feedback was collected. The training sessions received only positive feedback and suggestions for minor adjustments.

The first training session for students was offered in 2010 to third-year PharmD students at the Université de Montréal, and the sixth one was offered in December 2014. Around 1150 students participated in the course, of whom approximately 950 are now practicing pharmacists. After 5 years of practice and quality improvement, we observed in the role-playing activity and in exam results that the most effective way to reach our learning objectives was to inspire students and give them practical interview techniques. We give some examples below.

To help inspire students, a warm tone of voice is used throughout the session, especially for these citations that foster compassionate values in students:

“Worldwide, more people die from suicide than from all homicides and wars combined.”

—World Health Organization

“Learning to prevent suicide is like learning CPR: we hope never to use it, but it could save a life.”

—P. Vincent

“People who commit suicide don't really want to die, they only want to stop suffering.”

—P.-M. David

Here, we describe examples of interviewing tips we share with students. We suggest that pharmacists ask, “Hi, how is your treatment going?” to every patient the pharmacist serves, even for renewal of long-term treatments. This is particularly important for patients suffering mental illnesses. In addition, it is an ideal time to look at nonverbal cues and to ask more specific questions about a patient's mental state. If a patient looks distressed or verbalizes clear or covert ideas of self-harm, the first and only thing to do is to invite the patient into a closed office, where no disturbance is allowed. Steps should be taken to remove social barriers, such as taking off the lab coat. Then, an empathetic discussion about the patient's suffering helps build a therapeutic alliance. The heart of the intervention is to evaluate suicide risk. Hard questions must be asked: “Do you think you can hurt yourself?” or “Do you want to kill yourself?” “How? When? Are the means available?” “What makes you think it's going to be better if you die?” Thereafter, a plan is made with the patient depending on the danger: follow-up, call a suicide hotline, go home, call a friend, see a physician, or go to the hospital.

If all else fails, the pharmacist can call a suicide hotline, like 1-800-SUICIDE, with the patient in the office.

Evaluation of Learning Objectives

Learning objectives were properly evaluated in the form of case studies in formal exams, where 80% of the class was correct.

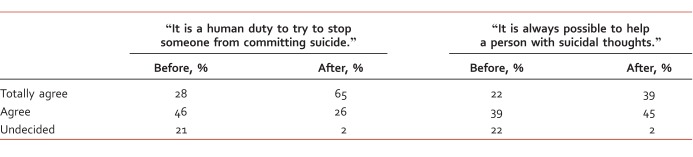

Moreover, in the fall 2014 session, our students completed the Attitude Towards Suicide Scale (20 items) before and after the training session.11 All of the students (196) responded before the course, showing a feeling of great duty to respond, and 170 responded 1 month after the final exam, showing a great commitment to the issue of suicide. The precourse attitudes were in accordance with the future professional role of our students. Interestingly, the after-course attitudes showed a statistically significant (t test) shift toward better attitudes in most of the items. The results of two particular item statements are interesting (Table).

TABLE:

Students' attitudes toward suicide before and after the training session

These results are under rigorous analysis and will be the subject of a subsequent publication.

Informal Appreciations

Students appreciated the session and were very grateful. Taboos, fears, and myths about suicide were lifted: “The suicide course gave me a better understanding of the issues surrounding suicide and better ways to behave with patients.”

Discussion/Conclusion

Initiatives such as the training program developed at the Faculty of Pharmacy at the Université de Montréal are very important in suicide prevention and precisely show what can be done with few resources. Integration into the psychiatry course also helps students have a more comprehensive understanding of mental health issues. These results show that pharmacy students achieved the learning objectives, potentially lowering suicide rates with more than 950 prepared sentinels located at a critical decision point in suicide prevention: the pharmacy.

Beyond formal evaluations and informal appreciation of the course, the pedagogic method is continually assessed and optimized. As a new method of evaluation it would be interesting to invite former students who now practice in the community to account for the changes made in knowledge, beliefs, and practices. Such an initiative will be taken next year.

AQPS's suicide hotline is getting more and more calls from pharmacists who, having helped a person with suicidal ideation, wish to validate their intervention. It is very encouraging and motivates us to continue the program in the Montreal region. One objective for the future is to create a network of inspired pharmacists to teach the art of talking to people suffering a mental crisis.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank all of our students for support in this quest. We also thank Simon D. Bourque for assistance with the manuscript.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Preventing suicide: a global imperative. World Health Organization, Luxembourg; 2014. p 89.

- 2. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2011: national estimates of drug-related emergency department visits. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2013. HHS Publication No.: (SMA) 13-4760, DAWN Series D-39. [cited 2 July 2015]. Available from: http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/DAWN2k11ED/DAWN2k11ED/DAWN2k11ED.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 3. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2003. [cited 2015 Jul 2]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lane J, Archambault J, Collins-Poulette M, Camirand R. . Prévention du suicide - guide de bonnes pratiques à l'intention des intervenants des centres de santé et de services sociaux [Internet]. Quebec City (QC): Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux; 2010. [cited 2015 Jan 26]. Available from: http://publications.msss.gouv.qc.ca/acrobat/f/documentation/2010/10-247-02.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lavigne JE, King DA, Lu N, Knox KL, Kemp JE. . Pharmacist and pharmacy staff knowledge and attitudes towards suicide and suicide prevention after a national VA training program. 2011; 14: A199- A200. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hamilton AAC. . Detecting and dealing with suicidal patients in the pharmacy. Can Pharm J (Ott). 2012; 145 4: 172- 3. DOI: 10.3821/145.4.cpj172. PubMed PMID: 23509546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gibson MR, Lott RS. . Suicide and the role of the pharmacist. J Am Pharm Assoc. 1972; 12: 457- 61. PubMed PMID: 5052954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Association québécoise de prévention du suicide [Internet]. Quebec City (QC): AQPS; [cited 2015. Jan 26]. Available from: http://www.aqps.info/. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Randall JR, Walld R, Finlayson G, Sareen J, Martens PJ, Bolton JM. . Acute risk of suicide and suicide attempts associated with recent diagnosis of mental disorders: a population-based, propensity score-matched analysis. Can J Psychiatry. 2014; 59 10: 531- 8. PubMed PMID: 25565686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Olfson M, Marcus SC, Tedeschi M, Wan GJ. . Continuity of antidepressant treatment for adults with depression in the United States. Am J Psychiatry. 2006; 163 1: 101- 8. DOI: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.101. PubMed PMID: 16390896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Renberg ES, Jacobsson L. . Development of a questionnaire on attitudes towards suicide (ATTS) and its application in a Swedish population. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2003; 33 1: 52- 64. DOI: 10.1521/suli.33.1.52.22784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]