Abstract

Benzodiazepine (BZD) abuse has reached epidemic levels and results in poor outcomes, particularly when combined with concomitant central nervous system depressants. BZDs are abused most commonly in combination with opioids and alcohol. Emergency department visits and related deaths have soared in recent years. In the absence of other medications or illicit substances, BZDs are rarely the sole cause of death. Prescription drug abuse has received more attention in recent years, yet much remains unknown about BZD abuse. BZDs have low abuse potential in most of the general population. A subset is at elevated risk of abuse, especially those with a history of a substance use disorder. Education, prevention, and identification are vital in reducing BZD abuse.

Keywords: benzodiazepines, abuse, dependence, misuse, polysubstance abuse, overdose

Introduction

Benzodiazepines (BZDs) first entered the US market in 1960. Chlordiazepoxide was the first in the class to be approved and introduced into clinical practice.1 BZDs quickly gained popularity because of their improved safety profile, most notably reduced respiratory depression, compared with older medications, particularly barbiturates.1,2

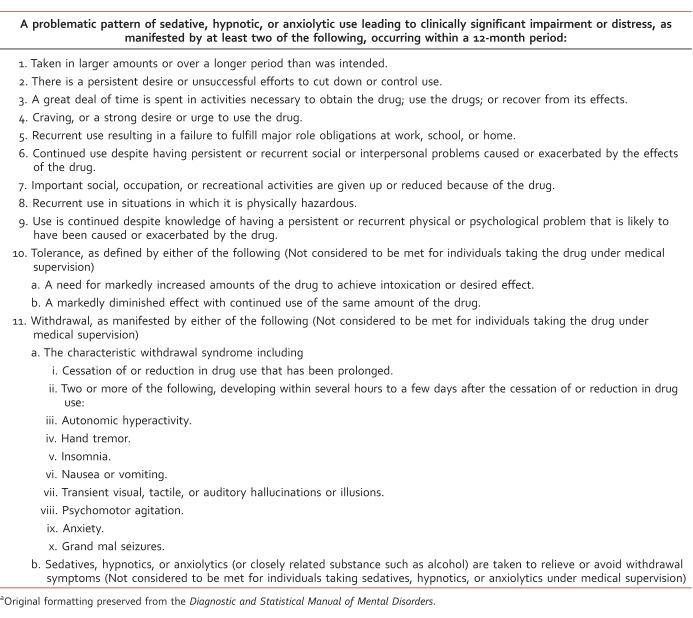

Nearly two decades after their discovery, researchers began to understand their mechanism of action.1 BZDs promote the binding of gamma-aminobutyric acid, or GABA, an inhibitory neurotransmitter, to the GABAA receptor, ultimately increasing ionic currents through the ligand-gated chloride channels.3 While researchers were uncovering the mechanism of action, clinicians began uncovering abuse and dependence.1 Diagnostic criteria for sedative, hypnotic, or anxiolytic use disorder are outlined in Table 1.4

TABLE 1: .

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition, diagnostic criteria for sedative, hypnotic, or anxiolytic use disordera

Although the addiction potential became widely known decades ago, much remains unknown about identifying individuals at risk for developing addiction and how to treat individuals abusing BZDs. Prescription drug abuse has received more attention in recent years, but most of the research has focused on prescription opioid abuse. Despite the risk of abuse and the introduction of safer alternatives, BZDs are one of the most prescribed classes of medications.5

Prevalence

Approximately 75 million prescriptions for BZDs were written in the United States in 2008.5 The prevalence of BZD use in the general population is 4% to 5%.5,6 Usage increases with age, and women are prescribed BZDs twice as often as men.5,7 Individuals prescribed opioids are considerably more likely to be prescribed a BZD.7,8

Most individuals take BZDs as prescribed, with less than 2% escalating to high doses and even less meeting more stringent criteria for abuse or dependence.9,10 In the general population, BZDs have low abuse potential.11 There is a subset of individuals at greater risk for BZD abuse, particularly those with a personal or family history of a substance use disorder.12 BZD abuse can be divided into two patterns, including deliberate or recreational abuse with the intention of getting high and unintentional abuse that begins as legitimate use but later develops into inappropriate use.13

BZD misuse and abuse is a growing problem. Approximately 2.3% to 18% of Americans have misused sedatives or tranquilizers for nonmedical use in their lifetime.14-16 Nearly 10% of these individuals met criteria for abuse or dependence.14 In 2010, there were an estimated 186 000 new BZD abusers.17 Emergency departments (EDs) have seen a sharp 139% increase in BZD-related visits.18 Older age and the presence of other drugs were associated with more serious outcomes, including death.19 The number of admissions to treatment programs for BZD abuse nearly tripled from 1998 to 2008. During this same time the number of all substance abuse treatment program admissions only increased by 11%.20

Risk Factors

Risk factors for BZD abuse and the demographics of this population have noteworthy differences from other substance abuse populations. First, non-Hispanic white is the predominant race. The role of gender is not well understood, because predominant gender in BZD abuse populations varies across published studies.15,16,20-22 Young adults ages 18 to 35 years comprise the largest portion of BZD abusers.20,21 BZD use, misuse, and abuse have a strong association with comorbid psychiatric disorders and personal or family history of substance use disorders.12,15,23,24 Comorbid psychiatric disorders are more common in BZD abusers than in other substance abuse populations.20,21 Approximately 40% of BZD abusers report a comorbid psychiatric disorder, highlighting the importance for clinicians to address both the underlying psychiatric disorder as well as the BZD abuse.20 Individuals with a history of alcohol abuse or dependence and antisocial personality disorder appear to be at a particularly elevated risk of BZD abuse in comparison with individuals without either disorder or individuals with alcohol abuse or dependence without antisocial personality disorder.22

Polysubstance Abuse

BZD abuse most commonly occurs in conjunction with other drugs. BZDs are typically secondary drugs of abuse for most, and a much smaller number report BZDs as the primary drug of abuse.20 The most frequent primary drugs of abuse include opioids (54.2%) and alcohol (24.7%).21 Approximately 1 in 5 individuals abusing alcohol also abuse benzodiazepines.22,25 BZDs are used to enhance the euphoric effects of other drugs; reduce the unwanted effects of drugs, such as insomnia due to stimulant use; and alleviate withdrawal.2,26,27 Individuals abusing BZDs in combination with other drugs consume much higher doses of BZDs than those abusing only BZDs.28

BZDs were involved in 408 021 ED visits in 2010, encompassing one third of all visits related to misuse and abuse of pharmaceuticals.18 ED visits specifically due to nonmedical use of BZDs in combination with opioids increased substantially, from 11 per 100 000 in 2004 to 34.2 per 100 000 in 2011. BZD involvement in opioid-related deaths increased dramatically, from 18% in 2004 to 31% in 2011. Opioids and BZDs are the two most common classes of prescription drugs involved in overdose deaths.29 Death rates for all prescription drugs have soared in recent years.30 Individuals who filled prescriptions for a BZD in addition to an opioid had a nearly 15-fold greater risk of drug-related death than individuals not prescribed either drug.31 Treatment program admissions for opioids and BZDs in combination skyrocketed, increasing by 570%, from 2000 to 2010.21

Opioids can cause prominent respiratory depression, and when combined with BZDs or alcohol, respiratory depression is compounded. The interaction between opioids and BZDs is complex. Respiration requires activation with excitatory amino acid receptors, and inhibition is mediated through GABA receptors. Respiration is controlled at medullary respiratory centers and receives input from peripheral chemoreceptors, which are stimulated by decreases in oxygen and increases in carbon dioxide.32 BZDs through increased GABA activity decrease respiratory motor amplitude and frequency. BZDs alone rarely cause death.2,12,33,34 BZDs are relatively weak respiratory depressants, but they can exert potent respiratory depression when used in combination with opioids.32 Actions of opioids at the μ opioid receptor result in reduced sensitivity to changes in oxygen and carbon dioxide concentrations and cause a reduction in tidal volume and respiratory frequency.3,32 Tolerance to opioid-induced respiratory depression is slow and incomplete in comparison with analgesic tolerance.32

Individuals receiving opioid replacement therapy with methadone or buprenorphine are particularly vulnerable to BZD misuse and abuse.35-37 Potential reasons for high rates of abuse in this population include high levels of psychologic distress; recreation purposes; sleep disturbances; the minimization of withdrawal; the reduction of negative effects of other substances, such as insomnia from amphetamines; and the belief that BZDs are not dangerous drugs.35,36 The prevalence of lifetime BZD abuse was 66.3% and current abuse was 50.8% in methadone replacement patients.36 More than half of the BZD users receiving methadone replacement did not start using a BZD until after starting the methadone replacement program.38 BZD use in combination with methadone is linked with a 60% increase in opioid-related death.39 A major advantage of buprenorphine over methadone is the ceiling effect, particularly with respiratory depression. When buprenorphine is taken with BZDs, the ceiling effect is no longer evident.40 In buprenorphine-experienced individuals, 67% reported taking the drug concurrently with BZDs. Approximately one third of individuals obtained the BZD from multiple or illicit sources.37

Alcohol is involved in 1 in 4 ED visits resulting from BZD abuse and is involved in 1 in 5 BZD-related deaths.18 Both alcohol and BZDs bind to distinct binding sites on the GABAA receptor, ultimately leading to synergistic drug actions. Pharmacodynamic interactions, although not fully understood, cause additive central nervous system depression, resulting in lower concentrations needed to cause fatalities.41 BZD-related ED visits in combination with alcohol were highest for individuals ages 45 to 54 years, but deaths were most frequent in individuals 60 years and older.42 Although alcohol plays a large role in multiple disease states, recent data indicate only 1 in 6 adults in the United States reported ever discussing alcohol use with a health care professional.43 Prescribers and pharmacists must provide education on the risks of combining alcohol and BZDs. In addition, health care professionals should make necessary interventions and referrals when problematic alcohol consumption is suspected or identified.

Abuse Liability

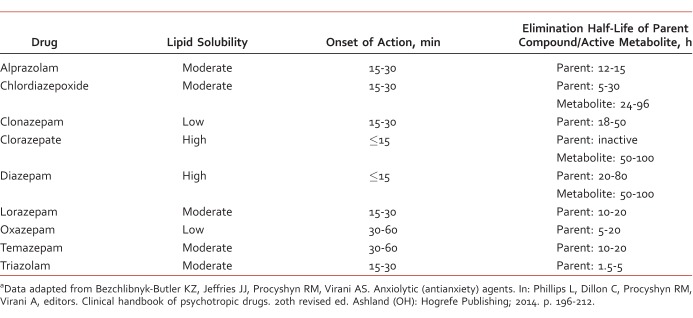

Differences in abuse potential within the BZD class have not been systematically studied. Pharmacokinetic differences are believed to contribute to the abuse potential. Lipophilicity is the chemical property responsible for the onset of action.44 Agents with higher lipophilicity and a shorter half-life appear to possess greater abuse potential.11,13 Chemical properties of common benzodiazepines are displayed in Table 2.44 Laboratory studies of subjective and reinforcing effects, medical professional experience, drug abusers' testimonies, and epidemiologic studies collectively indicate diazepam has the most abuse liability.45 Diazepam, alprazolam, and lorazepam had the highest subjective ratings for the high obtained in known drug abusers in comparison with oxazepam, clorazepate, and chlordiazepoxide, which appear to have lower abuse potential.2,11,45,46 Blinded recreational drug users perceived diazepam to be more valuable than equipotent doses of alprazolam and lorazepam.47 Nevertheless, alprazolam and clonazepam are the two BZDs associated with the most abuse-related ED visits; the rate of alprazolam involvement is more than double that of clonazepam.48 Alprazolam is the most prescribed BZD in the United States. More than 44 million alprazolam prescriptions were dispensed in 2009, nearly double the number of clonazepam, the second most prescribed BZD in the United States. Ease of access may play a role in alprazolam's abuse.49 Although pharmacokinetics and preferences among known drug users play a large role in abuse potential, prescribing patterns and the availability of agents likely play an equally important role.50

TABLE 2: .

Comparison of benzodiazepinesa

Implications for Health Care Professionals

Sources of prescription drug diversion are numerous and can include both health care–related and non–health care-related sources. The most frequently reported health care source of BZD diversion was a regular prescriber, followed by a script doctor (ie, a provider that sells prescriptions), doctor shopping (ie, an individual receives care from multiple providers for multiple prescriptions), and pharmacy diversion (ie, undercounting pills by pharmacy staff, employee theft).51 Recommendations for identifying high-risk individuals and reducing BZD abuse include obtaining a thorough personal and family substance use history, obtaining a urine drug screen, monitoring frequently for signs of abuse, reassessing the risks and benefits of ongoing therapy, prescribing a limited number of as-needed doses to reduce physiologic dependence, and differentiating carefully between physiologic dependence and addiction.12

Pharmacy shoppers, when defined as individuals receiving the same BZD prescription at 2 pharmacies within 7 days, are at 5.2 times greater risk for escalation to high doses of BZDs in comparison with other long-term BZD users.9 Doctor shoppers or individuals visiting 4 or more clinicians in a 6-month period are more likely to be female and have 2 times the risk of drug-related death compared with nonshoppers. Pharmacy shoppers, when defined as individuals who filled controlled substance prescriptions at 4 or more pharmacies within 6 months, had 3 times the risk compared with nonshoppers.31,32 Prescription drug monitoring programs aid in identifying prescription drug abuse.

More than 90% of all unintentional pharmaceutical overdose fatalities had at least one indicator of substance abuse. Indicators included known history of substance abuse, any drug diversion, nonmedical route of drug administration, more than 5 prescribers of controlled substances, contributory alcohol or illicit drug use, previous overdose, and current opioid replacement therapy.33 Both prescribers and pharmacists must be cognizant of the risks, use prescription drug monitoring programs, accurately identify drug abusers, and take appropriate action to mitigate risks. Additional strategies to reduce abuse include limiting the dose, quantity, and refills on each prescription.52 Diversion is greatest in young adults, and most obtain from a peer or family member.8,33,52

Past measures to reduce and restrict benzodiazepines were implemented in New York in 1989 in the form of triplicate prescriptions. The prescriber, pharmacy, and the state each received or retained one copy. Prescriptions were limited to a 30-day supply with no refills for most indications.53 Although successful at reducing overall benzodiazepine prescribing, these measures had many unintended consequences. The requirements led to a disproportionate reduction in prescribing to low-income and minority subpopulations and also led to a greater reduction in appropriate prescribing. Stringent requirements impeded access for appropriate medical use.53-56 Health care providers and lawmakers must be cautious when implementing laws and strategies to tackle prescription drug abuse to avoid hindering appropriate care.

Some clinicians argue the medical community has overreacted to the risks of BZD abuse, stating it may result in underprescribing of a safe and efficacious class of medications, and they argue for responsible but continued benzodiazepine prescribing.57 Although benzodiazepines possess abuse potential, particularly in substance abuse populations, it is crucial that risks be balanced with benefits. Prescribers must also weigh the risks of untreated illnesses. Poorly controlled or untreated anxiety or insomnia may increase the risk of alcohol relapse.58 Evidence-based pharmacotherapy and use of agents without abuse potential should be prescribed first-line and when appropriate, but BZDs may be indicated for some patients at elevated risk for abuse. When this occurs, provide thorough education on the risk of combining these drugs with alcohol or other substances, discuss diversion, prescribe a BZD with lower abuse potential, monitor for adverse effects, and monitor for inappropriate use.

Conclusion

Prescription drug abuse has reached epidemic levels. Current efforts to reduce associated morbidity and mortality have been unsuccessful. Rates continue to soar. Future research must be conducted to better understand the risk factors for BZD abuse. Despite risks of abuse and diversion, BZDs are a safe and efficacious class of medications and continue to have a place in therapy. Lawmakers and health care professionals will be tasked with reducing abuse while maintaining accessibility for appropriate patients. Reductions in inappropriate prescribing rather than all prescribing should be emphasized and encouraged. Education is vital. Health care professionals must be knowledgeable about abuse patterns and diversion trends. It is imperative that prescribers and pharmacists educate patients not only on the risks to themselves, but also the risks to others, to reduce medication sharing. It is critical to identify BZD abuse risk factors prior to prescribing, use safer alternatives, and make appropriate interventions to combat ongoing abuse. Increases of substance abuse treatment programs as well as funding for these programs in the future will be an essential component in battling the growing problem.

Footnotes

Disclosures: This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Fargo Veterans Affairs Health Care System. The contents do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the US government.

References

- 1. Wick JY. . The history of benzodiazepines. Consult Pharm. 2013; 28 9: 538- 48. DOI: 10.4140/TCP.n.2013.538 PubMed PMID: 24007886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Longo LP, Johnson B. . Addiction: part I: benzodiazepines--side effects, abuse risk and alternatives. Am Fam Physician. 2000; 61 7: 2121- 8. PubMed PMID: 10779253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Charney DS, Mihic SJ, Harris RA. . Hypnotics and sedatives. : Brunton LL, Lazo JS, Parker KL, . Goodman & Gilman's the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 11th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2006. p 401- 27. [Google Scholar]

- 4. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnosis and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. p 550- 56. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Olfson M, King M, Schoenbaum M. . Benzodiazepine use in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015; 72 2: 136- 42. DOI: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1763 PubMed PMID: 25517224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Paulozzi LJ, Zhang K, Jones CM, Mack KA. . Risk of adverse health outcomes with increasing duration and regularity of opioid therapy. J Am Board Fam Med. 2014; 27 3: 329- 38. DOI: 10.3122/jabfm.2014.03.130290 PubMed PMID: 24808111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Thangathurai D, Roby J, Roffey P. . Treatment of resistant depression in patients with cancer with low doses of ketamine and desipramine. J Palliat Med. 2010; 13 3: 235 DOI: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0312 PubMed PMID: 20178430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Havens JR, Walker R, Leukefeld CG. . Benzodiazepine use among rural prescription opioids users in a community-based study. J Addict Med. 2010; 4 3: 137- 9. DOI: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3181c4bfd3 PubMed PMID: 21769029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Soumerai SB, Simoni-Wastila L, Singer C, Mah C, Gao X, Salzman C, et al. Lack of relationship between long-term use of benzodiazepines and escalation to high dosages. Psychiatr Serv. 2003; 54 7: 1006- 11. DOI: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.7.1006 PubMed PMID: 12851438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2006 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: national findings. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2007. Report No.: DSDUH Series H-32. DHHS Publication No.: SMA 07-4293. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Roache JD, Meisch RA. . Findings from self-administration research on the addiction potential of benzodiazepines. Psychiatric Ann. 1995; 25 3: 153- 7. DOI: 10.3928/0048-5713-19950301-08. [Google Scholar]

- 12. el-Guebaly N, Sareen J, Stein MB. . Are there guidelines for the responsible prescription of benzodiazepines? Can J Psychiatry. 2010; 55 11: 709- 14. PubMed PMID: 21070698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. O'Brien CP. . Benzodiazepine use, abuse, and dependence. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005; 66 Suppl 2: 28- 33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Becker WC, Fiellin DA, Desai RA. . Non-medical use, abuse and dependence on sedatives and tranquilizers among U.S. adults: psychiatric and socio-demographic correlates. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007; 90 2-3: 280- 7. DOI: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.04.009 PubMed PMID: 17544227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goodwin RD, Hasin DS. . Sedative use and misuse in the United States. Addiction. 2002; 97 5: 555- 62. DOI: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00098.x PubMed PMID: 12033656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Simoni-Wastila L, Ritter G, Strickler G. . Gender and other factors associated with the nonmedical use of abusable prescription drugs. Subst Use Misuse. 2004; 39 1: 1- 23. DOI: 10.1081/JA-120027764 PubMed PMID: 15002942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, volume I: summary of national findings. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; [2012 Jul 2; cited 2015 Nov 11] Available from: http://archive.samhsa.gov/data/2k12/DAWN096/SR096EDHighlights2010.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 18. Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2012: highlights of the 2010 Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) findings on drug-related emergency department visits [Internet] Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; [2012 Jul 2; cited 2015 Nov 11] Available from: http://archive.samhsa.gov/data/2k12/DAWN096/SR096EDHighlights2010.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2014: benzodiazepines in combination with opioid pain relievers or alcohol: greater risk of more serious ED Visit outcomes [Internet] Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; [2014 Dec 18; cited 2015 Nov 11] Available from: http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/DAWN-SR192-BenzoCombos-2014/DAWN-SR192-BenzoCombos-2014.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Treatment episode data set, 2011: substance abuse treatment admissions for abuse of benzodiazepines [Internet] Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; [2011 Jun 2; cited 2015 Nov 11] Available from: http://atforum.com/documents/TEDS028BenzoAdmissions.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 21. Treatment episode data set, 2012: admissions reporting benzodiazepine and narcotic pain reliever abuse at treatment entry [Internet] Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; [2012 13 Dec; cited 2015 Nov 11] Available from: http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/BenzodiazepineAndNarcoticPainRelieverAbuse/BenzodiazepineAndNarcoticPainRelieverAbuse/TEDS-Short-Report-064-Benzodiazepines-2012.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ross HE. . Benzodiazepine use and anxiolytic abuse and dependence in treated alcoholics. Addiction. 1993; 88 2: 209- 18. DOI: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb00804.x PubMed PMID: 8106063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, Neale MC, Prescott CA. . Illicit psychoactive substance use, heavy use, abuse, and dependence in a US population-based sample of male twins. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000; 57 3: 261- 9. DOI: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.3.261 PubMed PMID: 10711912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Conway KP, Compton W, Stinson FS, Grant BF. . Lifetime comorbidity of DSM-IV mood and anxiety disorders and specific drug use disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006; 67 2: 247- 57. PubMed PMID: 16566620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Busto U, Simpkins J, Sellers EM, Sisson B, Segal R. . Objective determination of benzodiazepine use and abuse in alcoholics. Br J Addict. 1983; 78 4: 429- 35. PubMed PMID: 6140937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jones JD, Mogali S, Comer SD. . Polydrug abuse: a review of opioid and benzodiazepine combination use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012; 125 1-2: 8- 18. DOI: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.07.004. PubMed PMID: 22857878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Compton WM, Volkow ND. . Abuse of prescription drugs and the risk of addiction. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006; 83 Suppl 1: S4- 7. DOI: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.10.020 PubMed PMID: 16563663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Busto U, Sellers EM, Naranjo C, Cappell HD, Sanchez-Craig M, Simpkins J. . Patterns of benzodiazepine abuse and dependence. Br J Addict. 1986; 81 1: 87- 94. PubMed PMID: 2870731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jones CM, McAninch JK. . Emergency department visits and overdose deaths from combined use of opioids and benzodiazepines. Am J Prev Med. 2015; 49 4: 493- 501. DOI: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.03.040 PubMed PMID: 26143953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Drug overdose deaths--Florida, 2003-2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011; 60 26: 869- 72. PubMed PMID: 21734633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Peirce GL, Smith MJ, Abate MA, Halverson J. . Doctor and pharmacy shopping for controlled substances. Med Care. 2012; 50 6: 494- 500. DOI: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31824ebd81 PubMed PMID: 22410408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. White JM, Irvine RJ. . Mechanisms of fatal opioid overdose. Addiction. 1999; 94 7: 961- 72. DOI: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.9479612.x PubMed PMID: 10707430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hall AJ, Logan JE, Toblin RL, Kaplan JA, Kraner JC, Bixler D, et al. Patterns of abuse among unintentional pharmaceutical overdose fatalities. JAMA. 2008; 300 22: 2613- 20. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2008.802 PubMed PMID: 19066381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jones CM, Mack KA, Paulozzi LJ. . Pharmaceutical overdose deaths, United States, 2010. JAMA. 2013; 309 7: 657- 9. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2013.272. PubMed PMID: 23423407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lintzeris N, Nielsen S. . Benzodiazepines, methadone and buprenorphine: interactions and clinical management. Am J Addict. 2010; 19 1: 59- 72. DOI: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2009.00007.x PubMed PMID: 20132123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gelkopf M, Bleich A, Hayward R, Bodner G, Adelson M. . Characteristics of benzodiazepine abuse in methadone maintenance treatment patients: a 1 year prospective study in an Israeli clinic. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1999; 55 1-2: 63- 8. PubMed PMID: 10402150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nielsen S, Dietze P, Lee N, Dunlop A, Taylor D. . Concurrent buprenorphine and benzodiazepines use and self-reported opioid toxicity in opioid substitution treatment. Addiction. 2007; 102: 616- 22. DOI: 10.1111/j1360-0443.2006.01731.x PubMed PMID: 17286641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chen KW, Berger CC, Forde DP, D'Adamo C, Weintraub E, Gandhi D. . Benzodiazepine use and misuse among patients in a methadone program. BMC Psychiatry. 2011; 11 1: 90 DOI: 10.1186/1471-244X-11-90 PubMed PMID: 21595945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Leece P, Cavacuiti C, Macdonald EM, Gomes T, Kahan M, Srivastava A, et al. Predictors of opioid-related death during methadone therapy. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015; 57: 30- 5. DOI: 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.04.008 PubMed PMID: 26014916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nielsen S, Taylor DA. . The effect of buprenorphine and benzodiazepines on respiration in the rat. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005; 79 1: 95- 101. DOI: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.01.004. PubMed PMID: 15943948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Koski A, Ojanperä I, Vuori E. . Interaction of alcohol and drugs in fatal poisonings. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2003; 22: 281- 7. DOI: 10.1191/0960327103ht3240a PubMed PMID: 12774892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ogbu U, Lotfipour S, Chakravarthy B. . Polysubstance abuse: alcohol, opioids and benzodiazepines require coordinated engagement by society, patients, and physicians. West J Emerg Med. 2015; 16 1: 76- 9. DOI: 10.5811/westjem.2014.11.24720 PubMed PMID: 25671013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. McKnight-Eily LR, Liu Y, Brewer RD, Kany D, Lu H, Denny CH, et al. Vital signs: communication between health professionals and their patients about alcohol use--44 states and the District of Columbia, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014; 63 1: 16- 22. PubMed PMID: 24402468. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bezchlibnyk-Butler KZ, Jeffries JJ, Procyshyn RM, Virani AS. . Anxiolytic (antianxiety) agents. : Phillips L, Dillon C, Procyshyn RM, Virani A, . Clinical handbook of psychotropic drugs. 20th revised ed. Ashland (OH): Hogrefe Publishing; 2014. p 196- 212. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Griffiths RR, Wolf B. . Relative abuse liability of different benzodiazepines in drug abusers. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1990; 10 4: 237- 43. PubMed PMID: 1981067. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Iguchi MY, Griffiths RR, Bickel WK, Handelsman L, Childress AR, McLellan AT. . Relative abuse liability of benzodiazepines in methadone maintained populations in three cities. NIDA Res Monogr. 1989; 95: 364- 5. PubMed PMID: 2577040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Orzack MH, Friedman L, Dessain E, Bird M, Beake B, McEachern J, et al. Comparative study of the abuse liability of alprazolam, lorazepam, diazepam, methaqualone, and placebo. Int J Addict. 1988; 23 5: 449- 67. PubMed PMID: 3061941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Emergency department visits involving nonmedical use of selected prescription drugs--United States, 2004-2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010; 59 23: 705- 9. PubMed PMID: 20559200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Greenblatt DJ, Harmatz JS, Shader RI. . Psychotropic drug prescribing in the United States: extent, costs, and expenditures. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011; 31 1: 1- 3. DOI: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e318209cf05 PubMed PMID: 21192134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Pradel V, Delga C, Rouby F, Micallef J, Lapeyre-Mestre M. . Assessment of abuse potential of benzodiazepines from a prescription database using ‘doctor shopping' as an indicator. CNS Drugs. 2010; 24 7: 611- 20. DOI: 10.2165/11531570-000000000-00000 PubMed PMID: 20527997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ibañez GE, Levi-Minzi MA, Rigg KK, Mooss AD. . Diversion of benzodiazepines through healthcare sources. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2013; 45 1: 48- 56. PubMed PMID: 23662331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. McCabe SE, Boyd CJ. . Sources of prescription drugs for illicit use. Addict Behav. 2005; 30 7: 1342- 50. DOI: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.01.012 PubMed PMID: 16022931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Fisher J, Sanyal C, Frail D, Sketris I. . The intended and unintended consequences of benzodiazepine monitoring programmes: a review of the literature. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2011; 37 1: 7- 21. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2011.01245.x PubMed PMID: 21332565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ross-Degnan D, Simoni-Wastila L, Brown J, Gao X, Mah C, Cosler L, et al. A controlled study of the effects of state surveillance on indicators of problematic and non-problematic benzodiazepine use in a Medicaid population. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2004; 34 2: 103- 23. DOI: 10.2190/8FR4-QYY1-7MYG-2AGJ PubMed PMID: 15387395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Simoni-Wastila L, Ross-Degnan D, Mah C, Gao X, Brown J, Cosler LE, et al. A retrospective data analysis of the impact of the New York triplicate prescription program on benzodiazepine use in medicaid patients with chronic psychiatric and neurologic disorders. Clin Ther. 2004; 26 2: 322- 36. DOI: 10.1016/S0149-2918(04)90030-6 PubMed PMID: 15038954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pearson SA, Soumerai S, Mah C, Zhang F, Simoni-Wastila L, Salzman C, et al. Racial disparities in access after regulatory surveillance of benzodiazepines. Arch Intern Med. 2006; 166 5: 572 DOI: 10.1001/archinte.166.5.572 PubMed PMID: 16534046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Salzman C, Shader RI. . Not again: benzodiazepines once more under attack. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015; 35 5: 493- 5. DOI: 10.1097/JCP.0000000000000383. PubMed PMID: 26259040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ciraulo DA, Nace EP. . Benzodiazepine treatment of anxiety or insomnia in substance abuse patients. Am J Addict. 2000; 9 4: 276- 84. DOI: 10.1080/105504900750047346 PubMed PMID: 11155783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]