Abstract

Background:

All antipsychotics are associated with extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS). These can present as dysphagia, esophageal dysmotility, or aspiration, all of which may not be recognized as EPS.

Case Report:

A 62-year-old with schizophrenia, prescribed olanzapine 5 mg daily, presented agitated and endorsed difficulty swallowing. Speech therapy suggested her complaints were related to either reflux or dysmotility. Esophageal manometry showed her lower esophageal sphincter was not fully relaxing, and identified an esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction. Despite therapeutic dilation, oral intake remained poor. Following an increase in olanzapine, she developed EPS, her dysphagia worsened, and she was choking on food. Following a switch to aripiprazole her EPS and appetite improved, and she ceased complaining of dysphagia.

Discussion:

Dysphagia has been reported with first- and second-generation antipsychotics. A review of the second-generation antipsychotic literature identified case reports of dysphagia with clozapine (n = 5), risperidone (n = 5), olanzapine (n = 2), quetiapine (n = 2), aripiprazole (n = 1), and paliperidone (n = 1). Postulated mechanisms of antipsychotic-induced dysphagia include that it may be an extrapyramidal adverse reaction or related to anticholinergic effects of antipsychotics. Management of dysphagia includes discontinuing the antipsychotic, reducing the dose, dividing the dose, or switching to another antipsychotic. Complications of dysphagia include airway obstruction (eg, choking, asphyxia), aspiration pneumonia, and weight loss. Additional complications include dehydration, malnutrition, and nonadherence to oral medications.

Conclusion:

It is important to recognize symptoms of dysphagia and esophageal dysmotility in antipsychotic-treated patients. Intervention is necessary to prevent complications.

Keywords: dysphagia, antipsychotic, olanzapine, esophageal dysmotility

Background

Extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) are known adverse effects of antipsychotics. These can present as dysphagia, esophageal dysmotility, or aspiration, which may not be recognized as EPS. If untreated it can increase the risk for aspiration pneumonia, airway obstruction (eg, choking), or metabolic abnormalities that result from failure to thrive. Historical causes of sudden death in psychiatric hospitals included asphyxiation or choking. In April 2005 a warning was added to atypical antipsychotics regarding increased risk of death in elderly patients with dementia, which was updated in June 2008 to include all antipsychotics.1-3

A patient with a history of schizophrenia presenting with complaints of swallowing difficulty is discussed. Additionally, a literature review summarizing case reports of antipsychotic-induced dysphagia is presented along with potential mechanisms of this adverse effect.

Case Report

A 62-year-old African American woman with a history of schizophrenia, hypertension, hypothyroidism, and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) was admitted to the geriatric psychiatry service secondary to increased agitation and yelling, with a chief complaint of pain secondary to her GERD. Earlier in the day, she presented to an outside gastroenterology office without a scheduled appointment and became very disruptive when she could not be seen, shouting she could not swallow. She was subsequently referred to the emergency department for psychiatric evaluation. She made illogical statements in the emergency department, including that her jaw was slipping up and down, and that God was speaking to her about healing her. She continued to perseverate on her GERD. She reported recently stopping her psychotropic medications secondary to difficult, painful swallowing. Her husband confirmed that she was unable to swallow because of tightness in her esophagus, resulting in recent weight loss.

Her oral medications on admission included olanzapine orally disintegrating tablets (ODT) 5 mg at bedtime, escitalopram 10 mg daily, lorazepam 0.5 mg three times daily, mirtazapine 30 mg at bedtime, temazepam 7.5 mg at bedtime as needed (PRN) for insomnia, levothyroxine 25 mcg daily, metoprolol tartrate 25 mg every 12 hours, potassium chloride 10 mEq daily, pantoprazole 40 mg daily, and losartan 25 mg daily. She had previously been treated with risperidone 3 mg two times daily, but this was changed to olanzapine ODT during a recent hospitalization 1 month prior to this admission. Her nonpsychiatric medications were continued along with olanzapine ODT 5 mg at bedtime. Because of her hyperreligious presentation along with agitation, her mirtazapine and escitalopram were discontinued.

Her labs on admission were significant for hypokalemia (2.9 mmol/L) and mild thrombocytopenia (platelet count = 124 × 109/L). Her urinalysis and urine drug screen were both negative. Her thyroid-stimulating hormone was within normal limits at 1.2 milli–international units per liter.

On day 2, speech therapy suggested her complaints of difficulty swallowing were consistent with esophageal dysphagia related to either reflux or dysmotility. An esophagram from 1 year prior showed marked esophageal dysmotility while being treated with risperidone. Speech therapy recommended a full liquid diet, aspiration precautions, and a gastrointestinal (GI) consult. On day 4, her esophageal manometry showed her lower esophageal sphincter was not fully relaxing and identified an esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction.

Because of her continued delusions and behaviors she was continued on olanzapine ODT 5 mg at bedtime for 1 week. During this week she also received an average of 2 to 4 mg of intramuscular (IM) haloperidol PRN. Her intake remained poor, and she required intravenous fluids for tachycardia and dehydration (blood urea nitrogen = 14 mg/dL; serum creatinine = 0.7 mg/dL). On day 8, her olanzapine ODT was increased to 5 mg two times daily, and PRN was changed to olanzapine ODT and olanzapine IM. That day, she received a total of 12.5 mg of olanzapine, including PRNs. Oral benztropine 1 mg twice daily was also added to her regimen. On day 9, she began refusing her olanzapine secondary to choking. She continued to intermittently refuse her olanzapine and other medications during the next 2 days. During this time, she regularly ate 0% of her meals. A therapeutic dilation procedure was attempted during endoscopy on day 10 to improve her esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction.

She was adherent to her levothyroxine, pantoprazole, and docusate, but continued to refuse her oral olanzapine days 12 to 14. She did receive PRN olanzapine 2.5 mg IM during this time per involuntary administration order (maximum of 5 mg IM per day). Following the therapeutic dilation of her esophagus, along with her intermittent refusal of olanzapine, her intake increased to approximately 25% of meals; however, she continued to complain of difficulty swallowing. Her labs remained within normal limits. On days 15 and 16 she took 10 mg/d olanzapine. On day 17 she received olanzapine 2.5 mg IM in the morning and 10 mg orally at bedtime. Because of her continued poor intake she required 2 more intravenous fluid boluses for dehydration. She underwent a repeat manometry, which showed little change from the previous study. The GI service suggested the next step may be to consider Botox injections or surgical intervention. Following the increased dose of olanzapine, she was noted to have increased EPS, including parkinsonism, a shuffling gait, and a stooped/hunched posture. She continued to perseverate on her inability to swallow. The care partner working with her expressed concerns that she was choking on her food.

On day 19 the decision was made to switch her olanzapine to aripiprazole 10 mg daily secondary to lack of improvement in psychotic symptoms and increased adverse effects to olanzapine. During the next 48 hours her EPS improved, and she began eating 100% of meals, which remained consistent until discharge on day 25. Her repeat upper GI series on day 22 showed no esophageal obstruction lesions, no evidence of obstruction, and that she passed her barium swallow without difficulty. Her labs returned to baseline (blood urea nitrogen = 7 mg/dL; serum creatinine = 0.6 mg/dL). Speech therapy had been advancing her diet, and she tolerated solids without pain or any difficulty swallowing. Prior to discharge she ceased complaining of dysphagia. She was ultimately discharged on aripiprazole long-acting injection 400 mg monthly, with a 2-week oral overlap of aripiprazole 10 mg daily.

Discussion

This case describes a patient with schizophrenia who continued to complain of difficulty swallowing and the extensive workup performed trying to identify the cause. In retrospect, it appeared her dysphagia worsened with the change from risperidone to olanzapine a few weeks prior to admission. Her oral intake decreased on admission after reinitiation of her olanzapine and worsened with increased dosage. Although structural changes may have been related to her dysphagia, resolution of her dysphagia and EPS was not seen until her antipsychotic was changed from olanzapine to aripiprazole.

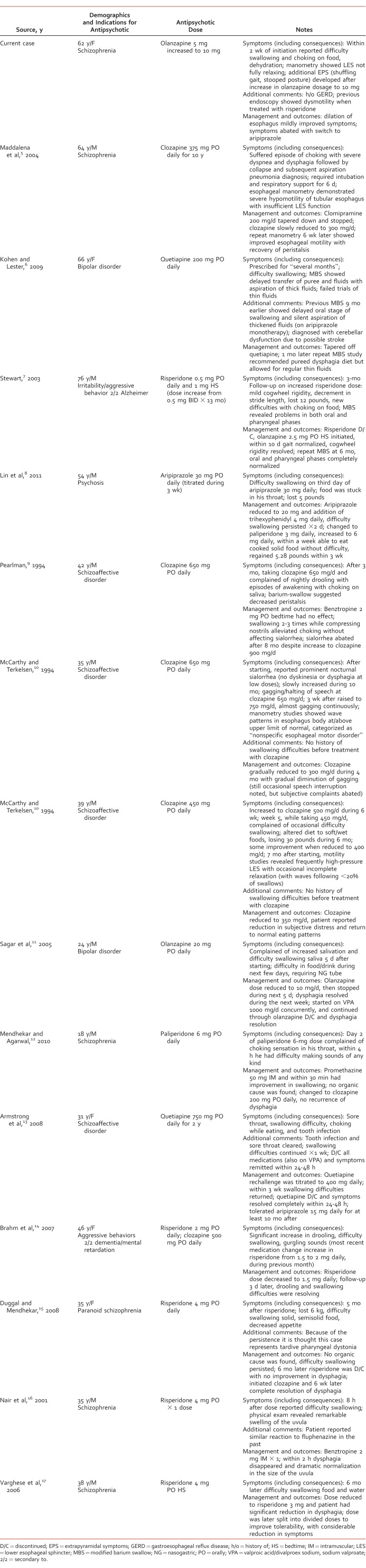

Dysphagia has been associated with many first-generation antipsychotics, including loxapine, fluphenazine, trifluoperazine, thioridazine, chlorpromazine, and haloperidol, in patients ages 38 to 79 years.1,4 Esophageal dysmotility with second-generation antipsychotics in the general adult population has been detailed in multiple case reports (Table),5-17 but less information is available regarding the geriatric population. Three cases were described in older adults (>60 years),5-7 and an additional 11 in the younger adult population. Our review of the literature with second-generation antipsychotics identified case reports with clozapine (n = 5), risperidone (n = 5), olanzapine (n = 2), quetiapine (n = 2), aripiprazole (n = 1), and paliperidone (n = 1). Four citations were not included in the Table because dysphagia was related to neuroleptic malignant syndrome (olanzapine and risperidone [n = 1]),18 angioedema (risperidone [n = 1]),19 scleroderma (haloperidol decanoate [n = 1]),20 and haloperidol rather than risperidone (n = 1).21 The 3 reports in patients older than 60 years are detailed below.

TABLE:

Case reports of dysphagia with second-generation antipsychotics

Maddalena et al5 described a case of clozapine-induced dysphagia in a 64-year-old man with chronic schizophrenia managed on clozapine for 30 years. The patient had suffered from swallowing difficulties 4 years prior to this admission while on clozapine 375 mg daily. The decision was therefore made to slowly taper clozapine to 300 mg daily. Peristalsis recovery and improved esophageal motility was shown on repeat manometry 6 weeks later.5

Kohen and Lester6 described a case of quetiapine-induced dysphagia in a 66-year-old woman with a history of bipolar disorder managed on quetiapine 200 mg daily for several months who was admitted to an inpatient psychiatric facility for worsening depressive symptoms. She did not exhibit any other EPS. Quetiapine was tapered off, and 1 month later a repeat modified barium swallow demonstrated improvement.6

Finally, Stewart7 described a case of risperidone-induced dysphagia in a 76-year-old man with history of Alzheimer dementia. Three months after his risperidone dose was increased by 0.5 mg/d, he experienced new difficulties with choking on food and weight loss of 12 pounds. Because of the new onset of swallowing difficulties, risperidone was discontinued and olanzapine 2.5 mg at bedtime was initiated. A repeat modified barium swallow 6 months later revealed oral and pharyngeal phases had completely normalized.7

Because there are minimal reports of this side effect published in medical journals, the Web site eHealthMe.com was searched for additional reports. This Web site attempts to capture real-word use of medications and identify rare or infrequent adverse effects. The Web site analyzes data from the US Food and Drug Administration along with social media. Patients and providers can also report adverse effects to the Web site. The percentage of patients experiencing an adverse effect is based on the number of reports of that specific adverse effect divided by the total number of adverse effect reports for that drug. Each second-generation antipsychotic was searched both as brand and generic, along with the keyword dysphagia. For example, as of September 16, 2016, a total of 14 579 patients have reported an adverse effect with olanzapine, and 1.26% (n = 183) reported dysphagia.22 Dysphagia was reported as an adverse event with aripiprazole, asenapine, clozapine, lurasidone, olanzapine, paliperidone, quetiapine, risperidone, and ziprasidone.22 Rates of reporting dysphagia ranged from 0.43% of adverse effect reports to 2.08% of adverse effect reports.22 Most reports occurred within the first 6 months of treatment, with the highest frequency occurring within the first month of therapy. There are some limitations to using this Web site as a reference, including the facts that the source of each report is unknown, dosage is not reported, and it is unknown if any reports are duplicated. The Web site does report top concurrently used medications, but it does not confirm which is more likely to be the causative agent of an adverse effect.

Postulated mechanisms of antipsychotic-induced dysphagia include that it may be an extrapyramidal adverse reaction, because dopamine blockade can cause dysphagia or laryngospasm.4,23 Some patients may experience dysphagia in combination with other EPS symptoms, whereas with others dysphagia may be the only EPS experienced.4 In this case, dysphagia was present with low-dose olanzapine 5 mg, and additional EPS were seen when the dosage was increased to 10 mg/d. Similarly, patients with Parkinson disease may develop oropharyngeal dysphasia or achalasia.24 Achalasia makes it harder for food to move from the esophagus to the stomach. In patients with achalasia, the lower esophageal sphincter does not relax well and esophageal peristalsis may be reduced.25 This patient's original esophageal manometry showed her lower esophageal sphincter was not fully relaxing. On the contrary, the anticholinergic effects of antipsychotics can impair the coordinated action of swallowing by weakening the parasympathetic signals, which are transmitted by muscarinic acetylcholine receptors.23 Dysphagia may also be a result of the concurrent dopamine blocking activity and anticholinergic effects.23 This patient was treated with olanzapine, one of the most anticholinergic second-generation agents, in combination with benztropine. Lastly, it has been postulated that dysphagia may be related to inhibition of the cough reflex, gag reflex, or swallow reflex.1

Medical causes of dysphagia include tachypnea secondary to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or severe GERD.4 Reduced esophageal motility in elderly patients with GERD can lead to delayed esophageal clearance and increased exposure to esophageal acid, and therefore result in dysphagia.24 Other at-risk populations include individuals with neurologic degenerative disease, dementia, stroke, Parkinson disease, and myasthenia gravis.23,24 Furthermore, elderly patients older than 75 years may be at increased risk secondary to muscle atrophy, structural changes in the oropharynx, reduced esophageal peristalsis, or cognitive impairment.6,23,24 This patient had severe GERD complaints, which were most likely worsened by esophageal dysmotility contributing to her dysphagia. Continuing pantoprazole was an important part of her treatment plan.

Complications of dysphagia include airway obstruction (eg, choking, asphyxia), aspiration pneumonia, and weight loss.4,23 Additional complications include dehydration, malnutrition, and, similar to this case, nonadherence to oral medications.23 Often antipsychotics with strong antihistamine properties, like olanzapine, are chosen in a certain subset of patients because of the potentially beneficial side effect of appetite stimulation. In the event that oral intake is reduced or weight loss occurs, it is important to consider evaluating for medication-induced dysphagia.

Management of dysphagia includes discontinuing the antipsychotic, reducing the dose, dividing the dose, or switching to another antipsychotic.4-8,10-17 In this case, symptoms improved with the switch from olanzapine to aripiprazole.

Conclusion

Although this article focuses primarily on second-generation antipsychotics, dysphagia can occur with any antipsychotic treatment. Although the elderly may be more susceptible to the complications associated with dysphagia, this adverse effect can impact any age group treated with antipsychotics. Elderly patients with comorbid GERD may be at even higher risk of developing dysphagia. It is important to recognize the symptoms of dysphagia and esophageal dysmotility in antipsychotic-treated patients. Intervention is necessary to reduce the risk of aspiration pneumonia; metabolic derangements secondary to reduced nutrition or dehydration; and choking or sudden death secondary to airway obstruction.

References

- 1. Fioritti A, Giaccotto L, Melega V. . Choking incidents among psychiatric patients: retrospective analysis of thirty-one cases from west Bologna psychiatric wards. Can J Psychiatry. 1997; 42 5: 515- 50. PubMed PMID: 9220116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Olanzapine prescribing information [Internet]. Indianapolis (IN): Eli Lily and Co. 2016. June [cited 2016 Aug 17]. Available from: http://www.dailymed.nlm.nih.gov

- 3. Safety alerts [Internet]. Silver Spring (MD): US Food and Drug Administration. 2008. June [cited 2016 Dec 15]. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/SafetyAlertsforHumanMedicalProducts/ucm110212.htm

- 4. Dziewas R, Warnecke T, Schnabel M, Ritter M, Nabavi DG, Schilling M, et al. . Neuroleptic-induced dysphagia: case report and literature review. Dysphagia. 2007; 22 1: 63- 7. DOI: 10.1007/s00455-006-9032-9. PubMed PMID: 17024549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Maddalena AS, Fox M, Hofmann M, Hock C. . Esophageal dysfunction on psychotropic medication: a case report and literature review. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2004; 37 3: 134- 8. DOI: 10.1055/s-2004-818993. PubMed PMID: 15138897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kohen I, Lester P. . Quetiapine-associated dysphagia. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2009; 10 4 Pt 2: 623- 5. DOI: 10.1080/15622970802176495. PubMed PMID: 18615368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stewart JT. . Dysphagia associated with risperidone therapy. Dysphagia. 2003; 18 4: 274- 5. DOI: 10.1007/s00455-003-0006-x. PubMed PMID: 14571332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lin TW, Lee BS, Liao YC, Chiu NY, Hsu WY. . High dosage of aripiprazole-induced dysphagia. Int J Eat Disord. 2011; 45 2: 305- 6. DOI: 10.1002/eat.20934. PubMed PMID: 21541978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pearlman C. . Clozapine, nocturnal sialorrhea, and choking. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1994; 14 4: 283 DOI: 10.1097/00004714-199408000-00013. PubMed PMID: 7962689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McCarthy RH, Terkelsen KG. . Esophageal dysfunction in two patients after clozapine treatment. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1994; 14 4: 281- 3. DOI: 10.1097/00004714-199408000-00012. PubMed PMID: 7962688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sagar R, Varghese ST, Balhara YP. . Dysphagia due to olanzapine, an antipsychotic medication. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2005; 24 1: 37- 8. PubMed PMID: 15778537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mendhekar DN, Agarwal A. . Paliperidone-induced dystonic dysphagia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010; 22 4: 451- v.e37 -451.e37. DOI: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.22.4.451-v.e37. PubMed PMID: 21037154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Armstrong D, Ahuja N, Lloyd AJ. . Quetiapine-related dysphagia. Psychosomatics. 2008; 49 5: 450- 2. DOI: 10.1176/appi.psy.49.5.450-a. PubMed PMID: 18794516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brahm NC, Fast GA, Brown RC. . Risperidone and dysphagia in a developmentally disabled woman. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2007; 9 4: 315- 6. PubMed PMID: 17934560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Duggal HS, Mendhekar DN. . Risperidone-induced tardive pharyngeal dystonia presenting with persistent Dysphagia: a case report. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2008; 10 2: 161- 2. DOI: 10.4088/PCC.v10n0213b. PubMed PMID: 18458730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nair S, Saeed O, Shahab H, Sedky K, Garver D, Lippmann S. . Sudden dysphagia with uvular enlargement following the initiation of risperidone which responded to benztropine: was this an extrapyramidal side effect? Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2001; 23 4: 231- 2. DOI: 10.1016/S0163-8343(01)00145-1. PubMed PMID: 11569473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Varghese ST, Balhara YP, George SA, Sagar R. . Risperidone and dysphagia. J Postgrad Med. 2006; 52 4: 327- 8. PubMed PMID: 17102565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yu M, Tadin D, Conrad EJ, Lopez FA. . Clinical case of the month: a 48-year-old man with fever and abdominal pain of one day duration. J La State Med Soc. 2015; 167 5: 237- 40. PubMed PMID: 27159603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Güneş F, Batgi H, Akbal A, Canatan T. . Angioedema--an unusual side effect of risperidone injection. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2013; 51 2: 122- 3. DOI: 10.3109/15563650.2013.765010. PubMed PMID: 23336748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shibley H, Pelic C, Kahn DA. . A case of paranoid schizophrenia complicated by scleroderma with associated esophageal dysmotility. J Psychiatr Pract. 2008; 14 2: 126- 30. DOI: 10.1097/01.pra.0000314321.32910.34. PubMed PMID: 18360200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lee JC, Takeshita J. . Antipsychotic-induced dysphagia: a case report. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2015; 17 5 DOI: 10.4088/PCC.15IO1792. PubMed PMID: 26835168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. eHealthMe [Internet]. Mountain View (CA): eHealthMe [cited 2016. Aug 9 and Sept 16]. Available from: http://www.ehealthme.com

- 23. Visser HK, Wigington JL, Keltner NL, Kowalski PC. . Biological perspectives: choking and antipsychotics: is this a significant concern? Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2014; 50 2: 79- 82. DOI: 10.1111/ppc.12062. PubMed PMID: 24606560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schnoll-Sussman F, Katz PO. . Managing esophageal dysphagia in the elderly. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2016; 14 3: 315- 26. DOI: 10.1007/s11938-016-0102-2. PubMed PMID: 27423892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. MedlinePlus [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine; [cited 2016. Oct 18]. Available from: http://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/000267.htm [Google Scholar]