Abstract

Introduction:

Excessive weight gain, glucose intolerance, and dyslipidemia are well-known physical side effects of the metabolic syndrome commonly associated with atypical antipsychotic (AAP) treatment. We review these side effects of AAPs and their monitoring and management strategies.

Methods:

A literature search was conducted to identify articles published on the prevalence, monitoring, and management of cardiometabolic side effects of AAPs.

Results:

Comparative risk of AAPs on weight gain, hyperlipidemia, glucose intolerance, and QT interval corrected for heart rate prolongation varies across the AAPs currently available. Likewise, pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic options investigated for management of these side effects, and monitoring those at appropriate intervals, differ based on the clinical condition and risk factors identified.

Discussion:

Atypical antipsychotics in general have little difference among them in short-term efficacy; however, the prevalence of their physical side effects substantially distinguishes them. It is of importance that clinicians carefully select AAPs bearing in mind the presence of risk factors, initiating patients directly on AAPs with a low risk of cardiometabolic side effects, and monitoring and managing those side effects at appropriate intervals.

Keywords: atypical antipsychotics, weight gain, hyperlipidemia, glucose intolerance, QTc prolongation

Introduction

During the last two decades, atypical antipsychotics (AAPs) have been increasingly popular among clinicians and patients because of the appealing decrease in extrapyramidal side effects in comparison with the first-generation antipsychotics.1 These drugs, however, are associated with a significant side effect burden ranging from metabolic disturbances, which include weight gain, type 2 diabetes, and dyslipidemia, to cardiovascular abnormalities, such as QT interval corrected for heart rate (QTc) prolongation.2 Although the contribution of AAPs to an increase in mortality rates is controversial, data show that overall life expectancy is 11 to 20 years shorter among patients with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia.3 In response to this growing issue, practice standards strongly encourage collaboration of medical disciplines to carefully monitor and manage these patients, so that they can receive the maximum benefit with minimal adverse effects.1,4 Although studies have identified the correlation between AAPs and the elevation regarding cardiometabolic risks, there seems to be a lack of a comprehensive review of the prevalence of these risks and their management. Hence, this review is to identify the prevalence of these physical side effects of AAPs, and to review the literature for monitoring and management strategies.

Changes in Body Weight

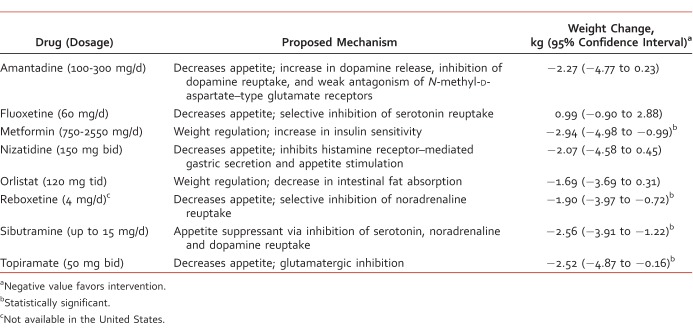

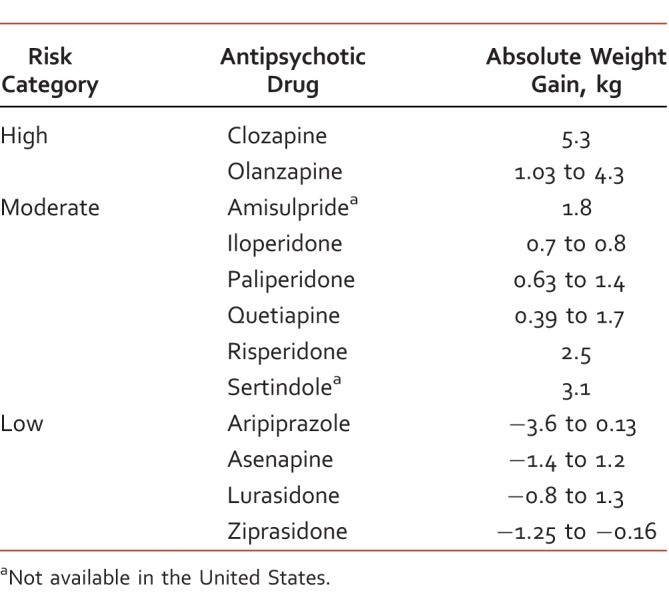

The risk and magnitude of weight gain vary across the AAPs available, and they have been comparatively studied by several meta-analyses with consistency in results.5,6 In the event a patient is experiencing unfavorable weight gain, a typical antipsychotic6,7 or an alternative AAP should be considered (Table 1),7,8 but clinicians should be cognizant of higher discontinuation of treatment and unguaranteed loss of body weight.9,10 Expert opinion indicates that the greatest amount of weight gain occurs within the first weeks of treatment and suggests that AAPs with a low risk of weight gain should be used at first initiation, whereas others should be reserved for situations of treatment resistance,8 although weight gain is a possibility for those who are drug naive even on low-risk AAPs.8,10 Genetics, lifestyle, and environmental factors, such as smoking, obesity, poor diet, and low levels of physical activity, may also play a prominent part despite the use of low-risk AAPs.11Apart from switching AAPs, other pharmacologic interventions have been investigated to reduce AAP-induced weight gain (Table 2).10,12-22 For nonpharmacologic management of AAP-induced weight gain, both nutritional counseling and cognitive behavioral therapy are effective.23 A review on cognitive behavioral therapy showed significant results in preventing and reversing AAP-induced weight gain, with a corresponding weight loss of 4.87 kg (95% confidence interval [CI], 2.6-7.1 kg) and 1.69 kg (95% CI, 0.6-2.8 kg), respectively.24 A recent systematic review showed that exercise interventions, such as cycling, muscle strengthening, and walking programs, in adults with serious mental illness had no noticeable changes in body mass index and body weight.11

TABLE 1: .

TABLE 2: .

Hyperlipidemia

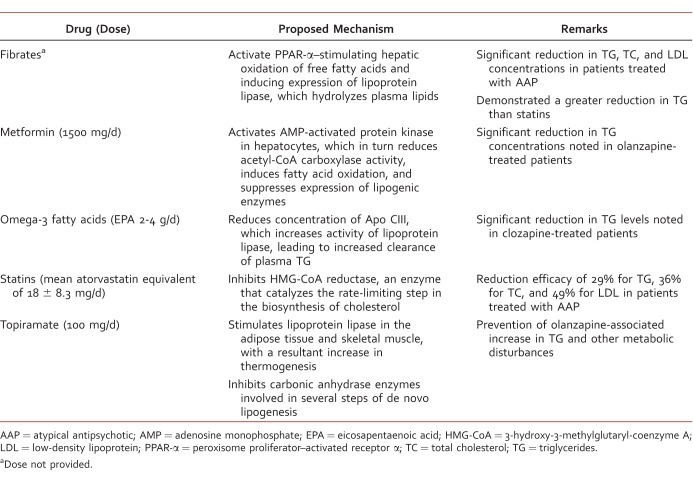

Hyperlipidemia, characterized by elevated serum cholesterol or triglyceride concentrations, is found to have a direct association with AAP use,25 although more recent work undertaken to better understand metabolic changes reveals fatty acid synthesis pathway deficits are present early in the course of schizophrenia and tend not to persist throughout its course.26 Those AAPs that confer an increased risk of weight gain correlate with an increased risk of hyperlidemia.25 A comparative meta-analysis found olanzapine use was associated with greater increases in serum cholesterol more than aripiprazole, risperidone, and ziprasidone. Likewise, quetiapine use was associated with greater increases in cholesterol than seen with risperidone and ziprasidone. There was no difference in producing an increase in cholesterol among patients prescribed clozapine, amisulpride, and quetiapine.27 Those with raised cholesterol may benefit from dietary advice, lifestyle changes, and/or treatment with statins.7 A variety of pharmacologic agents have been investigated for management of antipsychotic-induced hyperlipidemia (Table 3).28-30

TABLE 3: .

Glucose Intolerance

Individuals taking AAPs have a 2- to 3-fold increased prevalence in impaired glucose tolerance and diabetes compared with the general population.31 Among the AAPs in the market, there is an established link between diabetes and clozapine and olanzapine therapies, with fewer reports with quetiapine and risperidone.32 A large study encompassing 2.5 million individuals showed a significantly greater risk of developing diabetes after 12 months in patients on clozapine (odds ratio [OR], 7.44; 95% CI, 0.60-34.75) or olanzapine (OR, 3.10; 95% CI, 1.62-5.93) treatment.33 Patients taking risperidone had a nonsignificant increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) compared with nonantipsychotic users (OR, 2.2; 95% CI, 0.9-5.2) and those taking typical antipsychotics (OR, 1.6; 95% CI, 0.7-3.8).34 A head-to-head meta-analysis found olanzapine produced a greater increase in blood glucose than amisulpride, aripiprazole, quetiapine, risperidone, and ziprasidone.27 It is important to note that more recent work suggests direct effects of AAPs on insulin-sensitive tissues mediated by mechanisms independent of regulating eating behavior or appetite, and in the absence of psychiatric disease, weight gain, food intake, or hunger.35

If patients exhibit clinical signs and symptoms of hyperglycemia, clinicians should assess plasma glucose concentrations and consider medical or endocrine consultation, pharmacologic modification of the treatment regimen (eg, addition of hypoglycemic agents), active education of patients on lifestyle changes (eg, keeping active and having a low-carbohydrate, high-protein, and high-fiber diet), and the risks and benefits of switching the antipsychotic medication to one that carries less risk (Table 4)7,36 of precipitating weight gain or T2DM.37

TABLE 4: .

Cardiovascular Side Effects

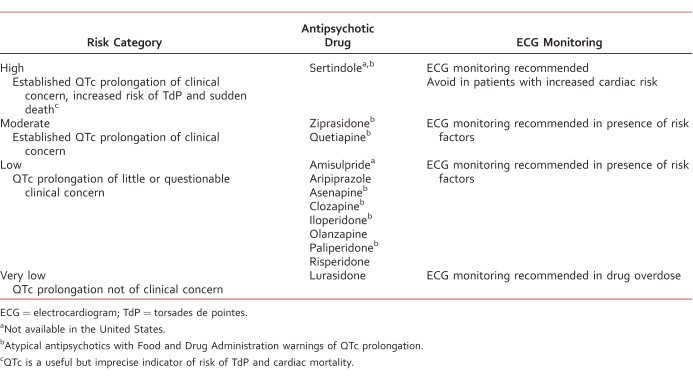

The QTc interval in healthy adults ranges from 380 to 450 ms depending on age and gender, and a prolonged QTc interval (>450 ms in men and >460 ms in women) has been associated with increased cardiovascular risk.38 QT prolongation is a known and established side effect of many medications, including certain AAPs, with the possibility of a QTc interval >500 ms increasing the risk of torsades de pointes (TdP), which can be potentially fatal.7,39 However, TdP is known to occur at therapeutic doses of AAPs with a QTc interval <500 ms.40 Thus, it can be challenging to determine the need to perform routine monitoring of QTc. This is due to the difficulty in establishing a threshold of clinical concern—when lower limits increase false positives and higher limits cause false negatives.41

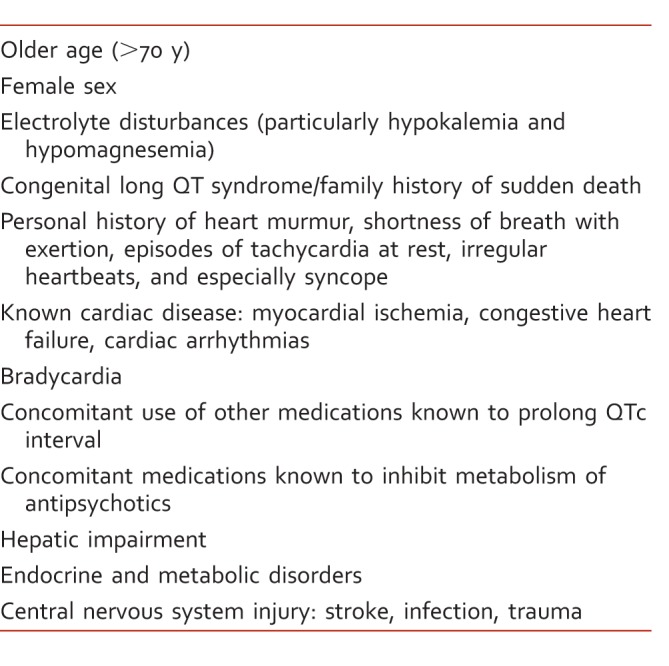

Electrocardiogram (ECG) monitoring both prior to treatment and regularly thereafter is recommended for those with (1) an increased cardiac risk after medical evaluation, (2) an established increased risk of TdP and sudden death with the antipsychotic prescribed, and (3) an overdose of antipsychotic medication.41 Patients at a higher risk (Table 5)42,43 should be initiated with an antipsychotic with minimal QTc prolongation (Table 6).7,41 If QTc prolongation is detected during treatment with AAPs, ECG should be repeated, and, if further prolonged, providers should continue to monitor ECG and serum electrolytes until stabilized. Discontinuation of the AAP and a referral to a cardiologist should be considered if there are persistent symptomatic complaints of syncope or palpitation.41

TABLE 5: .

TABLE 6: .

Conclusion

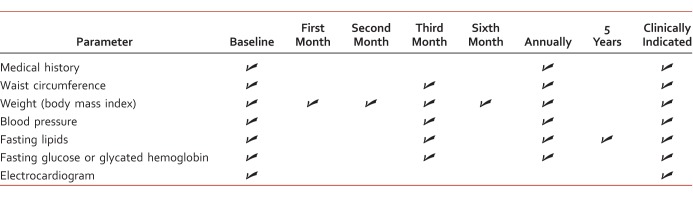

Although the onset of weight gain, hyperlipidemia, and elevated glucose concentrations are known side effects of AAP-induced metabolic syndrome, patients with mental health disorders continue to receive these agents. Atypical antipsychotics in general have little difference among them in efficacy5; however, the prevalence of their physical side effects differentiates them substantially. Therefore, the careful selection of an AAP is of essence, especially when a patient has a multitude of metabolic and cardiovascular risk factors. Antipsychotic polypharmacy is associated with an increased risk of these side effects and a longer duration of treatment with a greater severity (ie, higher body mass index).44 It is of benefit to initiate patients directly on AAPs with a low risk of metabolic side effects or switch those who are already on a high-risk AAP to a low-risk AAP. Current literature demonstrates that several AAPs prolong QTc interval, possibly resulting in TdP and sudden cardiac death. Consideration of risk factors, suitable AAP drug choices, dietary modifications, initiating suitable pharmacologic interventions, and monitoring at appropriate intervals (Table 7)7,45,46 with clinical end points are necessary to minimize the risk of metabolic and cardiovascular events of AAPs. In addition, metabolic and cardiovascular side effects outlined in this manuscript will likely apply to those newer AAPs; thus, it is of importance that clinicians coordinating care be vigilant of these cardiometabolic side effects and initiate standard management interventions promptly.

TABLE 7: .

Footnotes

Disclosures: All authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1. Shulman M, Miller A, Misher J, Tentler A. . Managing cardiovascular disease risk in patients treated with antipsychotics: a multidisciplinary approach. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2014; 7: 489- 501. DOI: 10.2147/JMDH.S49817. PubMed PMID: 25382979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hasnain M, Vieweg WV, Fredrickson SK, Beatty-Brooks M, Fernandez A, Pandurangi AK. . Clinical monitoring and management of the metabolic syndrome in patients receiving atypical antipsychotic medications. Prim Care Diabetes. 2009; 3 1: 5- 15. DOI: 10.1016/j.pcd.2008.10.005. PubMed PMID: 19083283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Laursen TM, Wahlbeck K, Hällgren J, Westman J, Ösby U, Alinaghizadeh H, et al. Life expectancy and death by diseases of the circulatory system in patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia in the Nordic countries. PLoS One. 2013; 8 6: e67133 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067133. PubMed PMID: 23826212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stahl SM, Morrissette DA, Citrome L, Saklad SR, Cummings MA, Meyer JM, et al. “Meta-guidelines” for the management of patients with schizophrenia. CNS Spectr. 2013; 18 3: 150- 62. DOI: 10.1017/S109285291300014X. PubMed PMID: 23591126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Leucht S, Cipriani A, Spineli L, Mavridis D, Örey D, Richter F, et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2013; 382 9896: 951- 62. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60733-3. PubMed PMID: 23810019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Allison DB, Mentore JL, Heo M, Chandler LP, Cappelleri JC, Infante MC, et al. Antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a comprehensive research synthesis. Am J Psychiatry. 1999; 156 11: 1686- 96. DOI: 10.1176/ajp.156.11.1686. PubMed PMID: 10553730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Taylor D, Paton C, Kapur S, . The Maudsley prescribing guidelines in psychiatry. 12th ed. West Sussex (UK): John Wiley & Sons; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Musil R, Obermeier M, Russ P, Hamerle M. . Weight gain and antipsychotics: a drug safety review. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2015; 14 1: 73- 96. DOI: 10.1517/14740338.2015.974549. PubMed PMID: 25400109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stroup TS, Byerly MJ, Nasrallah HA, Ray N, Khan AY, Lamberti JS, et al. Effects of switching from olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone to aripiprazole on 10-year coronary heart disease risk and metabolic syndrome status: results from a randomized controlled trial. Schizophr Res. 2013; 146 1-3: 190- 5. DOI: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.01.013. PubMed PMID: 23434503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bak M, Fransen A, Janssen J, van Os J, Drukker M. . Almost all antipsychotics result in weight gain: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014; 9 4: e94112 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094112. PubMed PMID: 24763306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pearsall R, Smith DJ, Pelosi A, Geddes J. . Exercise therapy in adults with serious mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2014; 14 1: 117 DOI: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-117. PubMed PMID: 24751159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Baptista T, Kin NM, Beaulieu S, de Baptista EA. . Obesity and related metabolic abnormalities during antipsychotic drug administration: mechanisms, management and research perspectives. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2002; 35 6: 205- 19. DOI: 10.1055/s-2002-36391. PubMed PMID: 12518268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Maayan L, Vakhrusheva J, Correll CU. . Effectiveness of medications used to attenuate antipsychotic-related weight gain and metabolic abnormalities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010; 35 7: 1520- 30. DOI: 10.1038/npp.2010.21. PubMed PMID: 20336059; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3055458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Baptista T, Rangel N, Fernández V, Carrizo E, ElFakih Y, Uzcátegui E, et al. Metformin as an adjunctive treatment to control body weight and metabolic dysfunction during olanzapine administration: a multicentric, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Schizophr Res. 2007; 93 1-3: 99- 108. DOI: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.03.029. PubMed PMID: 17490862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Atmaca M, Kuloglu M, Tezcan E, Ustundag B, Kilic N. . Nizatidine for the treatment of patients with quetiapine-induced weight gain. Hum Psychopharmacol Clin Exp. 2004; 19 1: 37- 40. DOI: 10.1002/hup.477. PubMed PMID: 14716710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bustillo JR, Lauriello J, Parker K, Hammond R, Rowland L, Bogenschutz M, et al. Treatment of weight gain with fluoxetine in olanzapine-treated schizophrenic outpatients. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003; 28 3: 527- 9. DOI: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300089. PubMed PMID: 12629532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Deberdt W, Winokur A, Cavazzoni PA, Trzaskoma QN, Carlson CD, Bymaster FP, et al. Amantadine for weight gain associated with olanzapine treatment. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005; 15 1: 13- 21. DOI: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2004.03.005. PubMed PMID: 15572269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Henderson DC, Copeland PM, Daley TB, Borba CP, Cather C, Nguyen DD, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of sibutramine for olanzapine-associated weight gain. Am J Psychiatry. 2005; 162 5: 954- 62. DOI: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.5.954. PubMed PMID: 15863798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Joffe G, Takala P, Tchoukhine E, Hakko H, Raidma M, Putkonen H, et al. Orlistat in clozapine- or olanzapine-treated patients with overweight or obesity. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008; 69 5: 706- 11. DOI: 10.4088/JCP.v69n0503. PubMed PMID: 18426261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kim JH, Yim SJ, Nam JH. A. 12-week, randomized, open-label, parallel-group trial of topiramate in limiting weight gain during olanzapine treatment in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2006; 82 1: 115- 7. DOI: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.10.001. PubMed PMID: 16326074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Poyurovsky M, Fuchs C, Pashinian A, Levi A, Faragian S, Maayan R, et al. Attenuating effect of reboxetine on appetite and weight gain in olanzapine-treated schizophrenia patients: a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2007; 192 3: 441- 8. DOI: 10.1007/s00213-007-0731-1. PubMed PMID: 17310385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wu RR, Zhao JP, Jin H, Shao P, Fang MS, Guo XF, et al. Lifestyle intervention and metformin for treatment of antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008; 299 2: 185- 93. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2007.56-b. PubMed PMID: 18182600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Álvarez-Jiménez M, Hetrick SE, González-Blanch C, Gleeson JF, McGorry PD. . Non-pharmacological management of antipsychotic-induced weight gain: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Psychiatry. 2008; 193 2: 101- 7. DOI: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.042853. PubMed PMID: 18669990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Faulkner G, Cohn T, Remington G. . Interventions to reduce weight gain in schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007; (1):CD005148. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD005148.pub2. PubMed PMID: 17253540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25. Meyer JM, Koro CE. . The effects of antipsychotic therapy on serum lipids: a comprehensive review. Schizophr Res. 2004; 70 1: 1- 17. DOI: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.01.014. PubMed PMID: 15246458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McEvoy J, Baillie RA, Zhu H, Buckley P, Keshavan MS, Nasrallah HA, et al. Lipidomics reveals early metabolic changes in subjects with schizophrenia: effects of atypical antipsychotics. PLoS One. 2013; 8 7: e68717 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068717. PubMed PMID: 23894336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rummel-Kluge C, Komossa K, Schwarz S, Hunger H, Schmid F, Lobos CA, et al. Head-to-head comparisons of metabolic side effects of second generation antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2010; 123 2-3: 225- 33. DOI: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.07.012. PubMed PMID: 20692814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yan H, Chen JD, Zheng XY. . Potential mechanisms of atypical antipsychotic-induced hypertriglyceridemia. Psychopharmacol (Berl). 2013; 229 1: 1- 7. DOI: 10.1007/s00213-013-3193-7. PubMed PMID: 23832387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Narula PK, Rehan HS, Unni KES, Gupta N. . Topiramate for prevention of olanzapine associated weight gain and metabolic dysfunction in schizophrenia: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Schizophr Res. 2010; 118 1-3: 218- 23. DOI: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.02.001. PubMed PMID: 20207521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ojala K, Repo-Tiihonen E, Tiihonen J, Niskanen L. . Statins are effective in treating dyslipidemia among psychiatric patients using second-generation antipsychotic agents. J Psychopharmacol. 2007; 22 1: 33- 8. DOI: 10.1177/0269881107077815. PubMed PMID: 17715204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Holt RIG, Peveler RC, Byrne CD. . Schizophrenia, the metabolic syndrome and diabetes. Diabet Med. 2004; 21 6: 515- 23. DOI: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2004.01199.x. PubMed PMID: 15154933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Haupt DW. . Differential metabolic effects of antipsychotic treatments. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006; 16: S149- 55. DOI: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2006.06.003. PubMed PMID: 16872808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gianfrancesco FD, Grogg AL, Mahmoud RA, Wang RH, Nasrallah HA. . Differential effects of risperidone, olanzapine, clozapine, and conventional antipsychotics on type 2 diabetes: findings from a large health plan database. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002; 63 10: 920- 30. PubMed PMID: 12416602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Koro CE. . Assessment of independent effect of olanzapine and risperidone on risk of diabetes among patients with schizophrenia: population based nested case-control study. BMJ. 2002; 325 7358: 243 DOI: 10.1136/bmj.325.7358.243. PubMed PMID: 12153919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Teff KL, Rickels MR, Grudziak J, Fuller C, Nguyen HL, Rickels K. . Antipsychotic-induced insulin resistance and postprandial hormonal dysregulation independent of weight gain or psychiatric disease. Diabetes. 2013; 62 9: 3232- 40. DOI: 10.2337/db13-0430. PubMed PMID: 23835329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lindenmayer JP, Czobor P, Volavka J, Citrome L, Sheitman B, McEvoy JP, et al. Changes in glucose and cholesterol levels in patients with schizophrenia treated with typical or atypical antipsychotics. Am J Psychiatry. 2003; 160 2: 290- 6. DOI: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.2.290. PubMed PMID: 12562575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Newcomer JW. . Metabolic risk during antipsychotic treatment. Clin Ther. 2004; 26 12: 1936- 46. DOI: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2004.12.003. PubMed PMID: 15823759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rautaharju PM, Surawicz B, Gettes LS, . Bailey JJ, Childers R, Deal BJ, et al. AHA/ACCF/HRS recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009; 53 11: 982- 91. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.014. PubMed PMID: 19281931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bednar MM, Harrigan EP, Anziano RJ, Camm AJ, Ruskin JN. . The QT interval. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2001; 43 5 Suppl 1: 1- 45. PubMed PMID: 11269621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hasnain M, Vieweg WV. . QTc interval prolongation and torsade de pointes associated with second-generation antipsychotics and antidepressants: a comprehensive review. CNS Drugs. 2014; 28 10: 887- 920. DOI: 10.1007/s40263-014-0196-9. PubMed PMID: 25168784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Shah AA, Aftab A, Coverdale J. . QTc prolongation with antipsychotics. J Psychiatr Pract. 2014; 20 3: 196- 206. DOI: 10.1097/01.pra.0000450319.21859.6d. PubMed PMID: 24847993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Vieweg WV. . New generation antipsychotic drugs and QTc interval prolongation. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2003; 5 5: 205- 15. DOI: 10.4088/PCC.v05n0504. PubMed PMID: 15213787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Khasawneh FT, Shankar GS. . Minimizing cardiovascular adverse effects of atypical antipsychotic drugs in patients with schizophrenia. Cardiol Res Pract. 2014; 2014: 273060 DOI: 10.1155/2014/273060. PubMed PMID: 24649390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Young SL, Taylor M, Lawrie SM. . “First do no harm”: a systematic review of the prevalence and management of antipsychotic adverse effects. J Psychopharmacol. 2015; 29 4: 353- 62. DOI: 10.1177/0269881114562090. PubMed PMID: 25516373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cohn TA, Sernyak MJ. . Metabolic monitoring for patients treated with antipsychotic medications. Can J Psychiatry. 2006; 51 8: 492- 501. PubMed PMID: 16933586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004; 27 2: 596- 601. PubMed PMID: 14747245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]