Abstract

Objective

Youth at clinical high risk (CHR) for psychosis often demonstrate significant negative symptoms, which have been reported to be predictive of conversion to psychosis and a reduced quality of life but treatment options for negative symptoms remain inadequate. Therefore, we conducted a systematic review and network meta-analysis of all intervention studies examining negative symptom outcomes in youth at CHR for psychosis.

Method

The authors searched PsycINFO, Medline, Embase, CINAHL, and EBM from inception to December 2016. Studies were selected if they included any intervention that reported follow-up negative symptoms in youth at CHR for psychosis. Treatment comparisons were evaluated using both pairwise and network meta-analyses. Due to the differences in negative symptom scales the effect sizes were reported as the standardized mean difference (SMD).

Results

Of 3027 citations, 32 studies met our inclusion criteria, including a total of 2463 CHR participants. The null hypothesis was not rejected for any of the 11 treatments. N-methyl-D-aspartate-receptor (NMDAR) modulators trended toward a significant reduction in negative symptoms compared to placebo (SMD = −0.54; 95% CI = −1.09 to 0.02; I2 = 0%, P = .06). In respective order of descending effectiveness as per the treatment hierarchy, NMDAR modulators were more effective than family therapy, need-based interventions, risperidone, amisulpride, cognitive behavioral therapy, omega-3, olanzapine, supportive therapy, and integrated psychological interventions.

Conclusions

Efficacy and effectiveness were not confirmed for any negative symptom treatment. Many studies had small samples and the majority were not designed to target negative symptoms.

Keywords: negative symptoms, clinical high risk, psychosis, schizophrenia, network meta-analysis, systematic review

Introduction

Attenuated psychotic symptoms have been the primary focus in individuals at clinical high risk (CHR) for psychosis both for meeting inclusion criteria using either the Structured Interview of Psychosis-Risk Syndromes (SIPS)1 or the Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental State (CAARMS)2 and for subsequent conversion to a full-blown psychotic disorder.3 Consequently, CHR individuals with predominantly negative symptoms and less severe attenuated positive symptoms are not necessarily perceived as needing treatment.4 Thus, interventional studies examining those at CHR for psychosis have predominately focused on the prevention of conversion or the reduction of attenuated psychotic symptoms, while largely ignoring negative symptoms.5 However, evidence suggests that negative symptoms in the CHR state may provide insight into underlying pathophysiological mechanisms in schizophrenia and lead to effective interventions.6,7

Youth at CHR for psychosis frequently present with a wide range of negative symptoms such as flat affect, alogia, anhedonia, avolition, emotional withdrawal, difficulty in abstract thinking, and deterioration in role functioning.8 Furthermore, CHR youth often demonstrate persistent and significant negative symptoms, which have been reported to be predictive of conversion to a psychotic disorder.9–13 Moreover, negative symptoms have been shown to reduce quality of life and impact long-term outcomes in CHR individuals,14–17 nevertheless they remain undertreated. In fact, even in schizophrenia, treatment development for negative symptoms has remained slow.18 There is a clear need for interventions for treating a range of symptoms in CHR youth,19 including negative symptoms. This has led to renewed interest in understanding the determinants of negative symptoms3 and designing interventions to decrease the burden of negative symptoms in CHR youth.20,21

A previous traditional meta-analysis examined the effects of different interventions on negative symptoms as a secondary outcome reported in 9 studies in a search performed in 2011 and only found a difference in negative symptoms in a single omega-3 trial considered to be of low quality.5,22 Since then interventional studies in CHR samples have increased substantially and are comprised of newer approaches such as N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) modulator interventions (glycine and d-serine), cognitive remediation therapy (CRT), and family therapy. Our review expands on the previous review, by including more than a 3-fold increase in interventional studies and the impact on negative symptoms as a primary outcome, not only in traditional pairwise meta-analyses, but in paired pre/post nonrandomized controlled studies meta-analyses and finally a network meta-analysis (NMA). The NMA allowed for indirect comparisons between treatment arms that have not been compared before (eg, omega-3 to glycine) that used a common comparator (eg, placebo). By including additional studies, new interventions, pre/post interventional studies, and indirect evidence, the evidence based on negative symptom interventions in CHR youth will be expanded.

Method

Protocol

This systematic review and NMA was conducted according to a prespecified protocol (PROSPERO [International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews] number: CRD42016049319) and reported in accordance with MOOSE and PRISMA guidelines.23–26 PRISMA checklists for both pairwise and network meta-analyses are provided in supplementary material 1.24,27

Search Strategy

The authors conducted an electronic database search of PsycINFO, Medline, Embase, CINAHL, and EBM from inception to December 2016. Full search details are shown in supplementary material 2. Each reviewer (A.P. and D.D.) independently performed title and abstract screening, and the full text of any study considered relevant according to the selection criteria was retrieved for detailed review. In addition, a Google Scholar search was conducted using the key words “psychosis risk” and “treatment” and both The International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/) and the Clinicaltrials.gov registry were searched using the terms “psychosis” and “risk.” Finally, reference lists of included articles were hand-searched for relevant citations.

Selection Criteria

Two reviewers (A.P. and D.D.) independently assessed the full text of each potentially relevant study for inclusion. Studies that met the following eligibility criteria were selected: (1) studies including participants at risk of psychosis meeting established criteria for CHR for psychosis, the attenuated psychosis syndrome (APS), the at-risk mental state (ARMS), ultra-high-risk (UHR), or schizotypy; (2) studies including observational interventions or experimental treatments; (3) studies reporting follow-up negative symptom scores reported using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS),28 the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS),29 the Scale of Prodromal Symptoms (SOPS),30 or the Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States (CAARMS),2 and (4) studies reporting a mean age between 12 and 30. Studies were not excluded based on languages. Case reports, review articles, editorials, nonintervention studies, and articles with overlapping datasets were excluded. Disagreements were resolved by a third author (J.A.).

Data Extraction

All data were extracted in duplicate and included study characteristics (author, publication year, country, study design, sample size, and negative symptom scale), participant details (number of CHR participants, mean ± SD age, number of males/percent male), and treatment characteristics (intervention, control, treatment duration, and negative symptom results). The following clinical outcome data were extracted: (1) mean ± SD negative symptom scores at follow-up and baseline, (2) sample size per treatment group, and (3) paired pre/post negative symptom scores for nonrandomized controlled studies with the P or t value of change in negative symptom scores. If articles only provided confidence intervals or standard error, an SD was obtained using the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook.31 Additional data were obtained by contacting corresponding authors, accessing ClinicalTrials.gov, obtaining follow-up articles, and extracting data from graphical format using GraphClick software.32 Articles published in languages other than English were translated using the Google Translator Toolkit.

Risk-of-Bias Assessment

For randomized studies included in the pairwise meta-analysis, risk of bias was evaluated using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias.31 To evaluate the quality of evidence associated with comparisons in the NMA colored edges (green = low risk, yellow= unclear risk, red= high risk) according to risk of bias for blinding of outcome assessments was estimated as the level of bias in the majority of the trials and weighted according to the number of studies in each comparison. The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach was use to evaluate the quality of evidence associated with the results in the NMA and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) criteria was applied to nonrandomized studies.33,34 Quality assessment did not influence the decision to include studies in the meta-analyses.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

Due to the differences in negative symptom scales the principal summary measures used across the majority of meta-analyses (ie, pairwise, paired nonrandomized controlled studies, and NMAs) were effect sizes calculated as Hedges g. Hedges g was reported as the standardized mean difference (SMD) of negative symptom scores at follow-up.35 Glycine and d-serine (herein: NMDAR modulators) are both amino acids that serve as neuromodulators in the brain by acting as a coagonist on the NMDAR in combination with glutamate,36,37 thus both were combined in pairwise and network meta-analyses. Treatment as usual, community care, monitoring, and needs focused interventions were pooled as need-based interventions in the meta-analyses due to similarities in design. Finally, due to expected differences between studies due to study design, CHR criteria, and the different treatment strategies, all results were combined using random-effects models.

For the primary analyses, direct treatment effects on negative symptoms from interventions (eg, 2 studies comparing omega-3 to placebo) were combined using a pairwise random-effects model by DerSimonian and Laird.38 If negative symptom scores were rated on the same scale the pooled mean difference (MD) was reported instead of the SMD. Thus, the likelihood of a reduction in negative symptoms in CHR youth who received a similar intervention was compared to a control. Direct treatment comparisons and risk of bias were analyzed using Review Manager 5.39 Paired pre/post nonrandomized controlled studies (eg, 3 aripiprazole studies reporting paired sample results) meta-analyses were analyzed using the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Software.38 Essentially, paired sample observations were pooled, thus measuring negative symptoms before and after receiving an intervention in the absence of a control.40,41

For the secondary analysis, RCTs treatment effects between individual intervention arms were evaluated using a random-effects multivariate NMA (greater details are provided for the NMA in supplementary material 3) assuming consistency and a common heterogeneity across all comparisons in the network model.42,43 The NMA allowed for indirect comparisons between treatment arms that have not been compared before (eg, omega-3 to glycine to antipsychotics) that used a common comparator (eg, placebo) by integrating direct evidence (eg, an existing study comparing omega-3 to placebo).44 Transitivity is a critical assumption in a NMA, which assumes that comparisons in the network model are consistent (similar effect modifiers such as age across all interventions).45–47 Simply put, whether it was equally likely that any CHR youth in the network could not be contraindicated to any of the treatments in the network,48 due to this schizotypy studies were excluded from the NMA. Thus, an inconsistency plot assuming loop-specific heterogeneity was produced to determine what might be important sources of inconsistency between direct and indirect evidence.49–52 In addition, baseline characteristics (age, CHR criteria) that might modify the treatment effect were restricted using an a priori inclusion criteria to prevent inconsistencies from being introduced into the model. Surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) plots were visually inspected to determine the most effective interventions compared to a superior hypothetical treatment, the faster a curve approaches one, the more probable it will be more effective.46,49 Publication bias was assessed using a network comparison-adjusted funnel plot.49 Data in the NMA were analyzed using Stata, version 13.1 (StataCorp LP). The graphical toolset in Stata called “networkplot” was utilized to produce graphical representations of the network evidence.49

Statistical heterogeneity was quantified using the I2 statistic with an I2 ≥ 50% indicating substantial heterogeneity and an I2 ≥ 75% indicating considerable heterogeneity. Inter-rater reliability for title and abstract screening was calculated using the kappa statistic. All SMDs (effect sizes) with a P < .05 were considered significant and as a general guide SMDs of 0.2 represented a small effect, 0.5 a medium effect, and 0.8 a large effect.53

Results

Search Yield

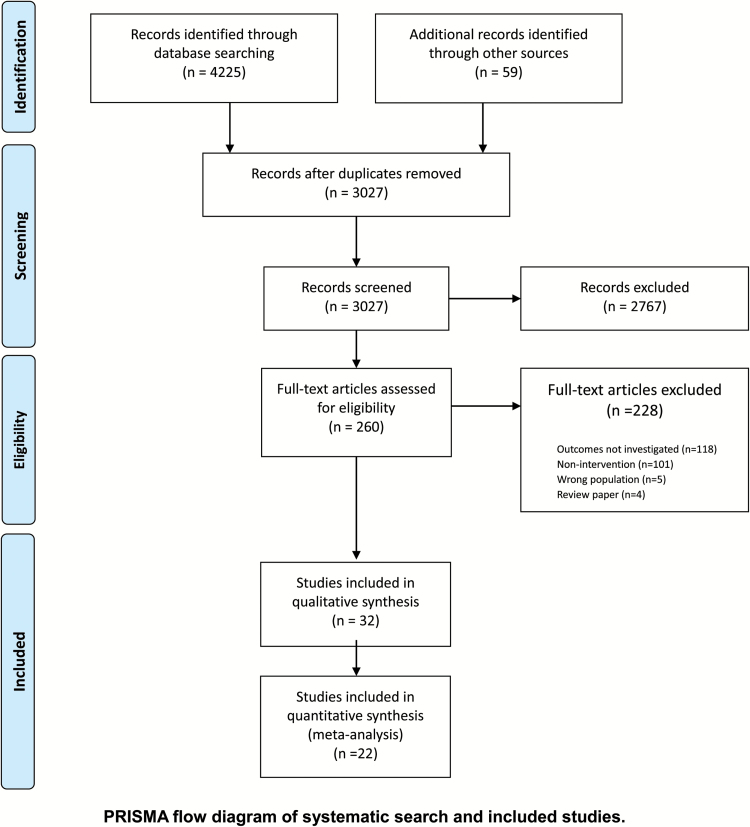

The search strategy generated 3027 unique citations; 2767 citations were excluded after reviewing title and abstract. The study eligibility agreement between reviewers for abstract and title screening was high (κ = 0.91). A total of 260 articles were retrieved for full-text review (figure 1). Of these, 32 primary studies were eligible for inclusion in our systematic review of which 22 were included in the meta-analyses. Reasons for exclusion included outcomes of interest not reported in the article (n = 118), nonintervention study (n = 101), wrong population (n = 5), and review paper (n = 4; figure 1). Among the 32 included studies, 13 were nonrandomized or noncontrolled observational studies and 19 were RCTs. Additional data for 9 studies was acquired from the corresponding authors.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of systematic search and included studies.

Study and Participant Characteristics

Characteristics of the 32 studies included in the systematic review are outlined in table 1. Of the 32 studies, 15 studies were conducted in North America,36,54–66 9 in Europe,67–75 4 in Australia,76–79 and 4 in Asia.80–83 Sixteen studies measured negative symptoms with the SOPS, PANSS (N = 10), SANS (N = 5), and the CAARMS (N = 3). The number of CHR participants ranged from 5 to 304, for a total of 2463 CHR participants. The mean age was 20.3 years (range = 15.6–27.2 years) and 1348 (54.7%) were male (range = 29–75%).

Table 1.

Details of Included Studies (N = 32)

|

Author + Year

|

Country | Study Design | Intervention (CHR n) |

Control

(CHR n) |

Included in Analysis | Sample Size | Treatment Duration (weeks) | CHR Patients | Negative Symptom Results | Negative Symptom Measure | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Age (M, SD) | Male (N, %) | ||||||||||

| Cognitive behavioral therapy | ||||||||||||

| Addington (2011) | Canada | RCT | CBT (27) | Supportive therapy (24) | NMA + pairwise | 51 | 24 | 51 | 21.0 (NR) | 36 (70) | Reduced negative symptoms in both groups | SOPS |

| Fusar (2015) | UK | Naturalistic | CBT (59) | CBT + AP (31) / CBT + AD (27) / CBT + AP + AD (33) | Not included in meta- analysis | 258 | NR | 258 | 22.9 (4.5) | 147 (57) | Patients with more severe negative symptoms preferred antidepressants | CAARMS |

| Ising (2016) | Netherlands | RCT | CBT + TAU (95) | TAU (101) | NMA + pairwise | 196 | 24 | 196 | 22.7 (NR) | 97 (49) | No significant reduction in negative symptoms in both groups | CAARMS |

| Family-based therapy | ||||||||||||

| McFarlane (2015) | USA | Regression discontinuity designa | Family-aided assertive community treatment (205) | Community care (NA) | Pre-/ post-analysis | 337 | 104 | 205 | 16.4 (3.3) | 116 (57) | Significant reduction in negative symptoms in treatment group | SOPS |

| Landa (2016) | USA | Open label | Group- and family-based CBT (6) | None (NA) | Pre-/ post-analysis | 6 | 15 | 6 | 19.5 (1.5) | 2 (33) | Reduced negative symptoms | CAARMS, PANSS |

| Miklowitz (2014) | USA + Canada | RCT | Family-focused therapy (66) | Enhanced care (63) | NMA | 129 | 24 | 129 | 17.4 (4.1) | 74 (57) | Reduced negative symptoms in both groupsb | SOPS |

| Omega-3 | ||||||||||||

| McGorry (2017) | Australia | RCT | Omega-3 ω-3 PUFA (1.4 g/day) + CBCM (153) | Placebo + CBCM (151) | NMA + pairwise | 304 | 24 | 304 | 19.1 (4.6) | 139 (46) | No reduction in negative symptoms | SANS |

| Amminger (2010) | Austria | RCT | Omega-3 PUFA (1.2 g/day) (41) | Placebo (40) | NMA + pairwise | 81 | 12 | 81 | 16.4 (NR) | 27 (33) | Reduced negative symptoms in intervention group | PANSS |

| Cadenhead (2017) | USA + Canada | RCT | Omega-3 (740mg of EPA and 400mg of DHA/ day) (65) | Placebo (62) | NMA + pairwise | 127 | 52 | 127 | 18.8 (NR) | 71 (56) | No significant difference in negative symptoms at follow-up | SOPS |

| Cognitive remediation | ||||||||||||

| Choi (2016) | USA | RCT | CRT (30) | Tablet computer games (32) | Pairwise | 62 | 8 | 62 | 18.35 (NR) | 32 (51) | No reduction in negative symptoms in either groupb | SOPS |

| Urben (2012) | Switzerland | RCT | CRT (7) | Computer games (5) | Not included in meta- analysis | 32 | 8 | 12 | 15.6 (NR) | 18 (56) | No reduction in negative symptoms | PANSS |

| Hooker (2014) | USA | Open label | CRT (14) | Computer games (NA) | Not included in meta- analysis | 28 | 8 | 14 | 21.9 (4.2) | 7 (50) | No reduction in negative symptoms | SOPS |

| Loewy (2016) | USA | RCT | CRT (50) | Computer games (33) | Pairwise | 83 | 8 | 83 | 18.2 (NR) | 42 (51) | No significant reduction in negative symptoms in both groups | SOPS |

| Piskulic (2015) | Canada | RCT | CRT (23) | Computer games (20) | Pairwise | 32 | 12 | 32 | 18.61 (NR) | 21 (66) | No reduction in negative symptoms in either groupb | SOPS |

| Rauchensteiner (2009) | Germany | Open label | CRT (10) | None (NA) | Not included in meta- analysis | 26 | 4 | 10 | 27.2 (5.3) | 7 (70) | No reduction in negative symptoms | PANSS |

| Integrated psychological therapies | ||||||||||||

| Nordentoft (2006) | Denmark | RCT | IPI (NA) | Standard treatment (NA) | Not included in meta- analysis | 79 | 104 | 79c | 24.9 (4.9) | 53 (67) | Reduced negative symptoms in intervention group | SANS |

| Wessels (2015) | Germanyd | RCT | IPI (53) | Supportive therapy (52) | NMA | 128 | 52 | 128 | 26.0 (NR) | 81 (63) | Reduced negative symptoms in both groups | PANSS |

| N-methyl-d-aspartate-receptor (NMDAR) modulators | ||||||||||||

| Kantrowitz (2016) | USA | RCT | d-serine (60 mg/ kg) (20) | Placebo (24) | NMA + pairwise | 35 | 16 | 35 | 19.5 (NR) | 23 (65) | Reduced negative symptoms in intervention group | SOPS |

| Woods (2013) | USA | Open labele | Glycine (0.8 g/kg/ day) (10) | None (NA) | Not included in meta- analysis | 10 | 8 | 10 | 17.3 (3.3) | 7 (70) | Medium effect sizes from treatment for negative symptoms | SOPS |

| Woods (2013) | USA | RCTe | Glycine (0.8 g/kg/ day) (4) | Placebo (4) | NMA + pairwise | 8 | 24 | 8 | 15.9 (NR) | 6 (75) | Medium effect sizes from treatment for negative symptoms | SOPS |

| Antipsychotics | ||||||||||||

| Aripiprazole | ||||||||||||

| Kobayashi (2009) | Japan | Open label | Aripiprazole (mean range dose 7.1-10.7 mg/day) (36) | None (NA) | Pre-/ post-analysis | 36 | 8 | 36 | 23.4 (5.6) | 15 (42) | Significant reduction in negative symptoms compared to baseline | SOPS |

| Liu (2012) | Taiwan | Open label | Aripiprazole (3.75 mg/day increased to 15 mg/day) (10) | Antipsychotic short exposure patients (NA) | Pre-/ post-analysis | 31 | 4 | 11 | 21.4 (NR) | 6 (54) | No reduction in negative symptoms in both groups | PANSS |

| Woods (2007) | USA | Open label | Aripiprazole (5–30 mg/day) (15) | None (NA) | Pre-/ post-analysis | 15 | 8 | 15 | 17.1 (5.5) | 8 (53) | Significant reduction in negative symptoms compared to baseline | SOPS |

| Risperidone | ||||||||||||

| Cannon (2002) | Finland | Open label | Risperidone (1.0–1.8 mg/day) (5) | None (NA) | Not included in meta- analysis | 16 | 12 | 5 | 15.6 (0.8) | 3 (60) | No significant reduction in social withdrawal | PANNS |

| McGorry (2002) | Australia | RCT | Risperidone (mean dose 1.3 mg/day) + CBT (31) | NBI (28) | NMA + pairwise | 59 | 24 | 59 | 20 (4.0) | 34 (58) | No significant reduction in negative symptoms in both groups | SANS |

| McGorry (2013) | Australiaf | RCT | Risperidone (0.5 mg/day increased to 2 mg/day) + CBT (43) or CBT + Placebo (44) | Supportive therapy + placebo (28) or monitoring (78) | NMA + pairwise | 193 | 52 | 193 | 18.1 (NR) | 81 (42) | Negative symptoms improved in all 3 groups | SANS |

| Other antipsychotics | ||||||||||||

| McGlashan (2006) | USA + Canada | RCT | Olanzapine (5–15 mg/day) (31) | Placebo (29) | NMA + pairwise | 60 | 52 | 60 | 17.7 (NR) | 39 (65) | No reduction in negative symptoms in intervention group | SOPS, PANSS |

| Ruhrmann (2007) | Germany | RCT | Amisulpride (mean dose 118.7 mg/day) + NFI (65) | NFI (59) | NMA | 124 | 12 | 124 | 25.6 (6.3) | 70 (57) | Reduced negative symptoms in intervention group | PANSS |

| Tsujino (2013) | Japan | Open label | Perospirone (mean dose 4.0 mg daily increased to 10.2 mg daily) (11) | None (NA) | Not included in meta- analysis | 11 | 26 | 11 | 26.7 (6.5) | 4 (36) | No significant reduction in negative symptoms | SOPS |

| Washida (2013) | Japan | Open label | Second generation anti- psychotics (17) | None (NA) | Not included in meta- analysis | 61 | 12 | 17 | 23.7 (4.4) | 5 (29) | CHR group showed major improvement in negative symptoms | PANNS |

| Woods (2017) | USA | RCT | Ziprasidone (20–160 mg/day) (24) | Placebo (27) | NMA | 50 | 24 | 50 | 22.25 (NR) | 32 (64) | No significant difference in negative symptoms at follow-up | SOPS |

| Mood stabilizers | ||||||||||||

| Berger (2008) | Australia | Open label | Low-dose lithium (450 mg/day) (25) | Monitoring (78) | Not included in meta- analysis | 103 | 52 | 103 | 19.0 (NR) | 45 (32) | No reduction in negative symptoms in either groupb | SANS |

CAARMS, comprehensive assessment of at-risk mental states; CBCM, cognitive-behavioral case management; CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy; CRT, cognitive remediation therapy; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; IPI, integrated psychological intervention; NFI, need-focused intervention; NR, not reported; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acid; SANS, Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms; SOPS, Scale of Prodromal Symptoms; TAU, treatment as usual.

aRisk-based allocation design.

bNegative symptom data obtained from corresponding authors.

cSample contained participants at risk of transition to psychosis based on schizotypy.

dArticle was translated from German to English using the Google Translator Kit.

eTwo studies were reported in one publication.

fMultinational trial: Australia, Switzerland, Germany, Denmark, Hong Kong, Austria, and Singapore.

Features of Treatment Interventions and Controls

The mean treatment duration was 26.3 weeks (range = 4–104 weeks). The nature of the interventions varied greatly between studies; CRT (N = 6), cognitive behavioral therapy (N = 3), aripiprazole (N = 3), family-based treatments (N = 3), NMDAR modulators (N = 3), risperidone (N = 3), omega-3 (N = 3), integrated psychological intervention (N = 2), amisulpride (N = 1), olanzapine (N = 1), low-dose lithium (N = 1), ziprasidone (N = 1), perospirone (N = 1), and second generation antipsychotics (N = 1). The control conditions varied as well; placebo (N = 7), computer games (N = 5), need-based interventions (N = 5), supportive therapy (N = 3), community care (N = 2), antipsychotic short-term exposure patients (N = 1), and combination therapies (N = 1). Eight studies did not use a control group. Seven interventions included additional participants (n = 308) that were not at CHR and consequently these participants were excluded from the current analyses.

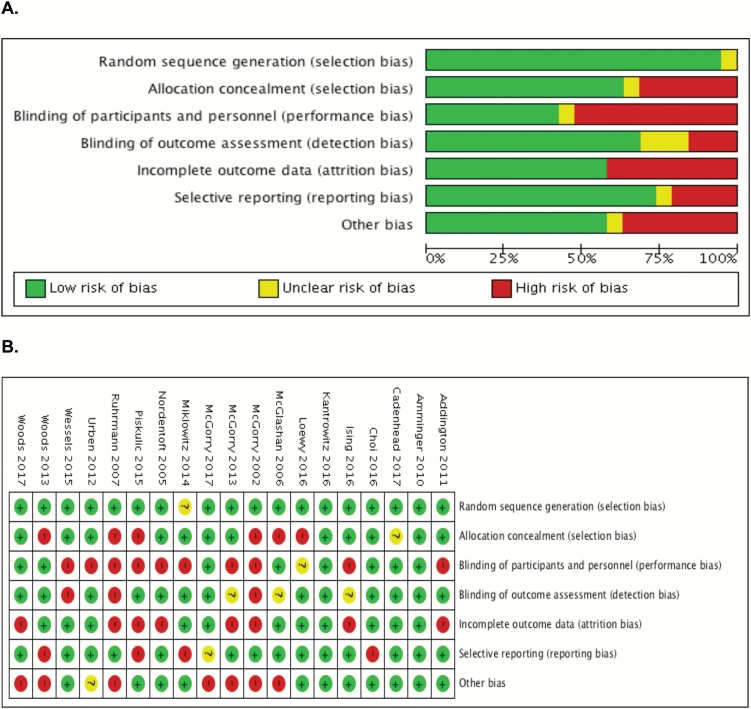

Risk-of-Bias Assessment

Quality assessment of RCTs (N = 19) is reported in figure 2. Most RCTs had a low risk of bias for random sequence generation (N = 18) and selective reporting (N = 14). Studies had a high risk of bias for allocation concealment (N = 6), attrition bias (N = 8), and other bias due to funding (N = 7). Blinding of outcome assessment had an unclear risk of bias (N = 3) and a high risk of bias (N = 3). Blinding of participants and personnel had the highest risk of bias (N = 10). Risk of bias assessment in the NMA plot (figure 3) for blinding of outcome assessments demonstrated that 7 had a low risk of bias, 5 had an unclear risk of bias, and 3 had a high risk of bias. Quality assessment for GRADE and NOS are provided in supplementary material 4.

Fig. 2.

(A) Risk of bias graph for RCTs: review authors’ judgments about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies. (B) Risk of bias summary: review author’s judgments about each risk of bias item for each included study.

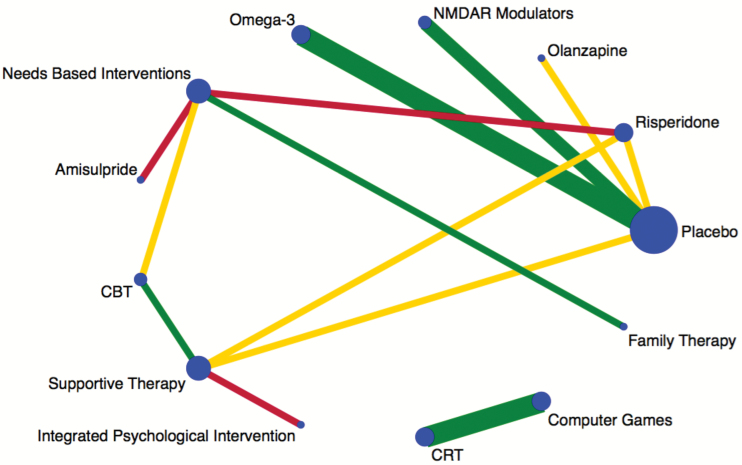

Fig. 3.

Plot of the negative symptom network. Nodes are weighted according to the number of studies including the respective interventions. Edges are weighted according to the number of studies including either that treatment or that comparison. Colored edges(green = low risk, yellow = unclear risk, red = high risk) according to risk of bias for blinding of outcome assessments, estimated as the level of bias in the majority of the trials and weighted according to the number of studies in each comparison.

Publication Bias

Visual inspection of the network comparison-adjusted funnel plot for symmetry indicated the absence of small study effects, see supplementary material 5.

Transitivity

Transitivity can be measured by inconsistency between direct and several indirect effect estimates using triangular or quadratic loops (eg, 4 treatments compared within the loop).49 The inconsistency plot produced one quadratic loop which found no significant evidence of inconsistency between direct and indirect evidence in the NMA, see supplementary material 5.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

NMDAR Modulators.

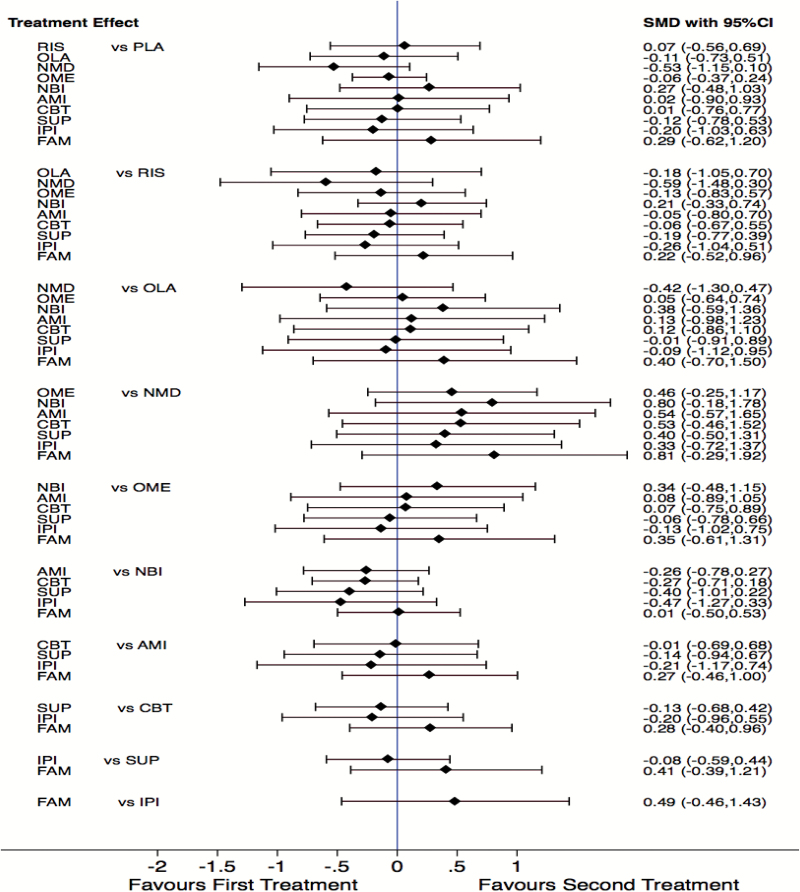

Three NMDAR modulator (glycine and d-serine) interventions reported on negative symptoms. Two NMDAR modulator (glycine and d-serine) interventions including 52 participants had sufficient data for meta-analysis (supplementary material 6). NMDAR modulator interventions were not associated with a significant reduction in negative symptoms compared to placebo (SMD = −0.54; 95% CI = −1.09 to 0.02; I2 = 0%; P = .06, supplementary material 6). In the NMA NMDAR modulators consistently ranked ahead of the majority of interventions; risperidone (SMD = −0.59; 95% CI = −1.48 to 0.30), olanzapine (SMD = −0.42; 95% CI = −1.30 to 0.47), amisulpride (SMD = 0.54; 95% CI = −0.57 to 1.65), CBT (SMD = 0.53; 95% CI = −0.46 to 1.52), supportive therapy (SMD = 0.40; 95% CI = −0.50 to 1.31), family therapy (SMD = 0.81; 95% CI = −0.29 to 1.92), need-based interventions (SMD = 0.80; 95% CI = −0.18 to 1.78), integrated psychological interventions (SMD = 0.33; 95% CI = −0.72 to 1.37), and omega-3 (SMD = 0.46; 95% CI = −0.25 to 1.17) (figure 4). Lastly, SUCRA plots of the absolute effects and rank test among the 11 treatments indicated that NMDAR modulators ranked higher than the other 10 treatments, but this is in the context of no statistically supported efficacy compared to placebo (supplementary material 5).

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of the network meta-analysis. PLA, placebo; RIS, risperidone; OLA, olanzapine; NMD, N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor modulators; OME, omega-3; NBI, need-based interventions; AMI, amisulpride; CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy; SUP, supportive therapy; IPI, integrated psychological interventions; FAM, family therapy.

Omega-3.

Three omega-3 studies reported on negative symptoms at 6 and 12 months. Three studies including 375 participants had sufficient data for meta-analysis (supplementary material 6). Omega-3 interventions were not associated with a significant reduction in negative symptoms at 6- or 12-month follow-up compared to placebo (SMD = −0.26; 95% CI = −0.86 to 0.35; I2 = 86%; P = .40 vs SMD = −0.06; 95% CI = −0.46 to 0.35; I2 = 63%; P = .78). In the NMA omega-3 demonstrated small to medium effects sizes for negative symptom reduction compared to need-based interventions (SMD = 0.34; 95% CI = −0.48 to 1.15) and family therapy (SMD = 0.35; 95% CI = −0.61 to 1.31). Omega-3 had no effect compared to risperidone (SMD = −0.13; 95% CI = −0.83 to 0.57), olanzapine (SMD = 0.05; 95% CI = −0.64 to 0.74), amisulpride (SMD = 0.08; 95% CI = −0.89 to 1.05), CBT (SMD = 0.07; 95% CI = −0.75 to 0.89), supportive therapy (SMD = −0.06; 95% CI = −0.78 to 0.66), and integrated psychological interventions (SMD = −0.13; 95% CI = −1.02 to 0.75) (figure 4).

Psychosocial Interventions.

Three CBT studies including 236 participants had sufficient data for meta-analysis (supplementary material 6). CBT interventions were not associated with a significant reduction in negative symptoms compared to controls (SMD = −0.12; 95% CI = −0.37 to 0.14; I2 = 0%; P = .37, supplementary material 6). In the NMA CBT appears to be more effective at reducing negative symptoms than need-based interventions (SMD = −0.27; 95% CI = −0.71 to 0.18) and family therapy (SMD = 0.28; 95% CI = −0.40 to 0.96) (figure 4).

Three family therapy studies reported negative symptoms; only 2 studies including 211 participants had sufficient data for a paired pre/post meta-analysis (supplementary material 6). Family therapy was not associated with a significant reduction in negative symptoms but demonstrated a large effect size in the absence of a control (SMD = −1.17; 95% CI = −3.29 to 0.95; I2 = 0%; P = .28, supplementary material 6). However, in the NMA family therapy did not appear to be more effective than any other treatment (figure 4).

Integrated psychological interventions could only be combined in the NMA due to having only one available study. Integrated psychological interventions appears to be more effective than need-based interventions (SMD = −0.47; 95% CI = −1.27 to 0.33), family therapy (SMD = 0.49; 95% CI = −0.46 to 1.43), CBT (SMD = −0.20; 95% CI = −0.96 to 0.55), amisulpride (SMD= −0.21; 95% CI = −1.17 to 0.74), and risperidone (SMD = −0.26; 95% CI = −1.04 to 0.51). Need-based interventions did not appear to be more effective than any other treatment (figure 4). Lastly, supportive therapy appears to be more effective than need-based interventions (SMD = −0.40; 95% CI = −1.01 to 0.22) and family therapy (SMD = 0.49; 95% CI = −0.46 to 1.43) in the NMA.

Antipsychotics.

Two risperidone studies (both included a CBT component) reported on negative symptoms at 6 and 12 months; both studies including 146 participants had sufficient data for meta-analysis (supplementary material 6). Risperidone interventions were not associated with a significant reduction in negative symptoms at 6- or 12-month follow-up (MD = 0.09; 95% CI = −7.63 to 7.81; I2 = 64%; P = .98 vs MD = 0.41; 95% CI = −4.45 to 5.28; I2 = 0%; P = .87, supplementary material 6). Risperidone in the NMA appears to be more effective at reducing negative symptoms than need-based interventions (SMD = 0.21; 95% CI = −0.33 to 0.74) and family therapy (SMD = 0.22; 95% CI = −0.52 to 0.96) (figure 4).

Three aripiprazole studies reported on paired pre/post negative symptoms; all 3 studies including 61 participants had sufficient data for meta-analysis (supplementary material 6). Aripiprazole interventions were associated with a significant reduction in negative symptoms (SMD = −0.66; 95% CI = −1.03 to −0.30; I2 = 0%; P < .01, supplementary material 6). Aripiprazole interventions could not be combined in the NMA due to having no comparable control.

Amisulpride and olanzapine could only be combined in the NMA due to having only one available study each. Amisulpride appears to be more effective at reducing negative symptoms than need-based interventions (SMD = −0.26; 95% CI = −0.78 to 0.27) and family therapy (SMD = 0.27; 95% CI = −0.46 to 1.00). Olanzapine appears to be more effective than need-based interventions (SMD = 0.38; 95% CI = −0.59 to 1.36) and family therapy (SMD = 0.40; 95% CI = −0.70 to 1.50) at reducing negative symptoms.

Cognitive Remediation Therapy.

Six CRT studies repor ted on negative symptoms; only 3 studies including 154 participants had sufficient data for meta-analysis (supplementary material 6). CRT interventions were not associated with a significant reduction in negative symptoms compared to computer games (SMD = 0.21; 95% CI = −0.12 to 0.53; I2 = 0%; P = .21, supplementary material 6). No CRT studies were assessed in the NMA due to having no comparable intervention, denoted by having no connecting node in the network plot (figure 3).

Discussion

We compared the effects of NMDAR modulators, omega-3, antipsychotics, psychosocial interventions, CRT, need-based interventions, and integrated psychological interventions in individuals at CHR for psychosis on negative symptoms using pairwise meta-analyses, paired pre/post meta-analyses, and a NMA. No treatments significantly reduced negative symptoms and in the NMA all confidence intervals overlapped the null line. NMDAR modulators were not significantly better than placebo but in the NMA emerged more effective than risperidone, olanzapine, omega-3, amisulpride, CBT, supportive therapy, family therapy, need-based interventions, integrated psychological interventions, and combination therapies at reducing negative symptoms in CHR youth. Omega-3 interventions were found to be better than family therapy and need-based interventions in the NMA, but the effect sizes were usually small and were not significant compared to placebo in pairwise meta-analysis. Antipsychotics fared better than need-based interventions and family therapy in the NMA. Aripiprazole produced a significant reduction in negative symptoms but in the absence of a control group. Psychosocial interventions (CBT, family therapy, supportive therapy) were not more efficacious than placebo in reducing negative symptoms in both pairwise meta-analyses and the NMA. Both Omega-3 and risperidone pairwise meta-analyses demonstrated significant amounts of heterogeneity, however, in meta-analyses of very few studies such as this the I2 may not be accurate.84

Antipsychotics function primarily to block dopamine receptors, targeting positive symptoms, but seem to have little impact on negative symptoms in CHR youth compared to placebo.21 However, amisulpride and olanzapine both showed favorable results at the reduction of negative symptoms compared to other interventions such as need-based interventions and family therapy. An improvement in negative symptoms has been shown in amisulpride and olanzapine treatment with low-dose amisulpride (50–100 mg/day) and olanzapine in schizophrenia patients.85,86 Finally, none of the needs based interventions, CBT, and supportive therapy arms targeted negative symptoms in CHR and thus the results may be merely emphasizing the fact that these interventions were not designed to reduce negative symptoms.

NMDAR antagonists (phencyclidine and ketamine) can induce cognitive and behavioral changes comparable to patients with schizophrenia, thus formulating the NMDAR modulator postulate.20,37,87 In addition to the results here for NMDAR modulators in CHR youth, there are mixed results in improving negative symptoms for those with schizophrenia.88 Only 3 studies on NMDAR modulators in CHR youth exist to date, all of which have been pilot studies. Pilot studies represent a foundational step in investigating novel interventions such as NMDAR modulators. However, the NMDAR modulator pilot studies should be interpreted with caution as they require subsequent implementation in larger samples to determine a precise and meaningful effect size that is generalizable beyond the inclusion and exclusion criteria of the respective pilot design.89 Moreover, NMDAR modulator studies to date suffer from small sample sizes and the results of the NMA should be interpreted with caution until larger trials investigating the impact of NMDAR modulator in CHR samples emerge. Lastly, glycine and d-serine are not equally encouraging for the reduction of negative symptoms in CHR, which was demonstrated in the results of the pairwise meta-analysis. Efficacy of NMDAR modulators has varied, with patients needing larger doses of glycine while d-serine is tolerated in much smaller doses.62 Thus, N-acetylcysteine (NAC) may be an important compound to investigate in CHR in regards to negative symptoms due to its effects on NMDAR functioning and having a mild side-effect profile.90,91 Taking these limitations into account, NMDAR modulators taken in conjunction with psychosocial interventions and antipsychotics may prove to be an effective approach to treating the array of symptoms (eg, positive, negative, disorganized) that CHR youth face, nevertheless larger trials are needed.

Strengths and limitations

This review included 32 interventions with more than 2400 CHR youth. We used a broad and rigorous approach to identify interventions, extracted outcomes in duplicate, and used sound meta-epidemiological methodology. Thus, making this review the most comprehensive systematic review of negative symptom interventions in CHR to date. However, our study has several limitations. First, there is a relative paucity of high-quality literature on interventions in CHR on negative symptoms. Although the majority of studies identified were RCTs, a large amount of attrition occurred, which may have introduced important biases in the meta-analyses. However, most RCTs had relatively balanced dropouts across groups and handled incomplete data with an intention-to-treat analysis, which may have attenuated attrition bias. Thus, attrition appears to be inherent in CHR samples and not due to a lack of efficacy in the RCTs. In addition, almost half of the RCTs had either an unclear or high risk of bias for blinding of outcome assessments which has been shown to be associated with an inflated estimate of effects.31

Second, paired pre/post nonrandomized controlled studies can only establish an association between an intervention and negative symptoms. Therefore, even though aripiprazole nonrandomized controlled studies showed a significant decrease in negative symptoms and family interventions demonstrated a large effect size, neither results establish causality and should be interpreted with extreme caution. These studies are plagued with methodical problems such as confounders, sampling biases, and effect modifiers and rated poorly in quality assessments.

Third, the primary outcome for the majority of interventions was conversion to a psychotic disorder, a concomitant of attenuated psychotic symptoms. Consequently, studies were designed to decrease conversion rates, while negative symptoms were primarily juxtaposed as a secondary outcome with a battery of other secondary outcomes (eg, cognition). Indeed, the recent meta-analysis of 168 RCTs that examined treatment for negative symptoms in schizophrenia resonates with our results that almost no studies were designed to target negative symptoms, nor used the required design for efficacy. In addition, it was observed that the literature was inconsistent on persistent negative symptoms, which was a subject that was not addressed in CHR trials.18 The NIMH-MATRICS consensus on negative symptoms and a more recent perspective on methodological issues in negative symptom trials contend that the design of future trials targeting negative symptoms should take into account a variety of methodical considerations including a co-primary measure of functional improvement, optimal duration, investigation into interventions and agents that could have broad spectrum implications for both positive and negative symptoms, and addressing the strengths and weaknesses of available instruments for measuring negative symptoms.92,93 Albeit, neither of the abovementioned perspectives considered CHR participants in their consensus, thus any future consensus on negative symptoms should include schizophrenia, first episode, and high-risk researchers. Furthermore, most of the psychosocial treatments did not target negative symptoms failing to include elements designed to diminish negative symptoms. Thus, it may very well be that CBT in CHR, without a negative symptom component, is not effective for negative symptom reduction.

Fourth, we pooled a variety of negative symptom scales using SMD which may have important implications when interpreting the current results. The majority of studies employed the SOPS scale for measuring negative symptoms in CHR which measures social anhedonia, avolition, decreased expression of emotion, decreased experience of emotions and self, decreased ideational richness, and a deterioration of role function. However, it does not measure 2 of the 5 core negative symptoms, alogia and restricted affect, which has been established by the NIMH consensus. Interestingly, a new scale, the Prodromal Interview of Negative Symptoms (PINS) has recently been developed as a result of the consensus conference recommendations.94 To date, however, this scale has only reported preliminary data on psychometric properties although plans for further development are underway.94

Fifth, the current results cannot disambiguate between primary negative symptoms (pathophysiological schizophrenia mechanisms) and secondary negative symptoms (other mechanisms such as depression). CHR youth samples often have high comorbid rates of depression and anxiety, which has been shown to be correlated with negative symptoms such as anhedonia.95 None of the current studies utilized methods to reduce the influence of secondary negative symptoms nor provided a distinction between the two, which may have confounded the relationship between negative symptom improvement or lack of improvement and their respective interventions. To this point, our analysis cannot amend analytically issues of pseudospecificity and the current studies have important limitations related to the underreporting of both the persistence of negative symptoms in CHR and transience of these symptoms.

Lastly, the effect of omega-3 on negative symptoms in both the pairwise and NMA was strongly influenced by one small study conducted in 2010,22 which failed to be replicated in 2 subsequent studies.65,79 Thus, although omega-3 demonstrated a small effect compared to family therapy this would primarily be due to the presence of the 2010 study the data. Moreover, all omega-3 confidence intervals overlapped the null line in the NMA and it was not significant when compared to placebo in both analyses. Thus, the results of omega-3 should be interpreted with caution.

Directions for future research

The findings of the current systematic review lead to 2 potential areas for future research. First, NMDAR modulators (d-serine and glycine) were shown to have a moderate effect on negative symptoms and merit further investigations into other NMDAR modulators such as d-alanine and sarcosine, which may be effective early intervention for negative symptoms.96 In addition, NMDAR modulators have shown promising results in the reduction of positive symptoms in CHR and may represent a treatment for wider range of symptomatology than psychotherapies or antipsychotics.97 However, larger studies are needed to assess NMDAR modulators effects on quality of life, long-term outcomes of negative symptoms, and transition to a psychotic disorder21 as well as side effects and compliance issues.

Second, aripiprazole nonrandomized controlled studies produced a moderate effect on negative symptoms in the absence of a control group. However, one study compared aripiprazole to short-term antipsychotics in sample of 10 CHR individuals and found no significant difference between groups.81 Due to the poor study designs and being significantly under powered, a large randomized control trial is needed to understand the overall effect of aripiprazole on negative symptoms compared to controls.

Lastly, due to the pluripotent nature of the CHR state, those at risk may never develop psychosis, albeit many still suffer from reduced quality of life and low functioning and require evidence-based treatments.98

Conclusions

In conclusion, this review contained information on clinical trials of 11 treatment approaches. Support for efficacy or effectiveness did not reach statistical significance for any of the treatments. Many of the relevant studies had small samples and the majority was not designed to target negative symptoms, thus reducing their clinical importance with respect to negative symptoms. Future research should be undertaken in the form of large clinical trials that target negative symptoms in CHR.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data are available at Schizophrenia Bulletin online.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Mental Health (RO1MH105178 awarded to J.A.). D.D. is funded through the Novartis Chair in Schizophrenia Research held by J.A. A.P. declares no relevant financial interests.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge librarian Helen L. Robertson for help with conducting the literature search for review. In addition, the authors would like to acknowledge Dr Miklowitz (University of California Los Angeles), Dr Barnaby and Dr McGorry (University of Melbourne), Dr Choi (Hartford HealthCare), Dr Kristin Cadenhead (The University California, San Diego), Dr Scott Woods (Yale), Dr Ising (Parnassia Groep), Dr van der Gaag (Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam), and Dr Fusar-Poli (King’s College, London) for agreeing to share study data and to Dr Bechdolf (Charite-Universitätsmedizin Berlin) for providing his article in German.

References

- 1. McGlashan T, Walsh B, Woods S.. The Psychosis-Risk Syndrome: Handbook for Diagnosis and Follow-up. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yung AR, Yuen HP, McGorry PD, et al. Mapping the onset of psychosis: the Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39:964–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fusar-Poli P, Borgwardt S, Bechdolf A, et al. The psychosis high-risk state: a comprehensive state-of-the-art review. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:107–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fusar-Poli P, Van Os J. Lost in transition: setting the psychosis threshold in prodromal research. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2013;127:248–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stafford MR, Jackson H, Mayo-Wilson E, Morrison AP, Kendall T. Early interventions to prevent psychosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2013;346:f185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fusar-Poli P, Borgwardt S. Integrating the negative psychotic symptoms in the high risk criteria for the prediction of psychosis. Med Hypotheses. 2007;69:959–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lencz T, Smith CW, Auther A, Correll CU, Cornblatt B. Nonspecific and attenuated negative symptoms in patients at clinical high-risk for schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2004;68:37–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Piskulic D, Addington J, Cadenhead KS, et al. Negative symptoms in individuals at clinical high risk of psychosis. Psychiatry Res. 2012;196:220–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kwapil TR, Kwapil TR. Social anhedonia as a predictor of the development of schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. 1998;107:558–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mason O, Startup M, Halpin S, Schall U, Conrad A, Carr V. Risk factors for transition to first episode psychosis among individuals with ‘at-risk mental states’. Schizophr Res. 2004;71:227–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yung AR, Phillips LJ, Yuen HP, et al. Psychosis prediction: 12-month follow up of a high-risk (“prodromal”) group. Schizophr Res. 2003;60:21–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Demjaha A, Valmaggia L, Stahl D, Byrne M, McGuire P. Disorganization/cognitive and negative symptom dimensions in the at-risk mental state predict subsequent transition to psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38:351–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Devoe D, Cadenhead K, Cannon T, et al. SU127. Negative symptoms in youth at clinical high risk of psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2017;43(suppl 1):S207–S207. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bechdolf A, Pukrop R, Köhn D, et al. Subjective quality of life in subjects at risk for a first episode of psychosis: a comparison with first episode schizophrenia patients and healthy controls. Schizophr Res. 2005;79:137–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nelson B, Yuen HP, Wood SJ, et al. Long-term follow-up of a group at ultra high risk (“prodromal”) for psychosis: the PACE 400 study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:793–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Domínguez-Martínez T, Kwapil TR, Barrantes-Vidal N. Subjective quality of life in At-Risk Mental State for psychosis patients: relationship with symptom severity and functional impairment. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2015;9:292–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wood S, Lin A, Nelson B, McGorry P, Yung A. Negative symptoms in the at-risk mental state—association with transition to psychosis and functional outcome. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2014;8:23. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fusar-Poli P, Papanastasiou E, Stahl D, et al. Treatments of negative symptoms in schizophrenia: meta-analysis of 168 randomized placebo-controlled trials. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41:892–899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Carpenter WT, Schiffman J. Diagnostic concepts in the context of clinical high risk/attenuated psychosis syndrome. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41:1001–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kantrowitz JT, Javitt DC. N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor dysfunction or dysregulation: the final common pathway on the road to schizophrenia?Brain Res Bull. 2010;83:108–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kantrowitz JT, Woods SW, Petkova E, et al. “D-serine for the treatment of negative symptoms in individuals at clinical high risk of schizophrenia: a pilot, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised parallel group mechanistic proof-of-concept trial”: correction. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Amminger GP, Schafer MR, Klier CM, et al. Indicated prevention with long-chain omega-3 fatty acids in young people at ultra-high risk for psychosis: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2010;4:7.20199476 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hutton B, Salanti G, Caldwell DM, et al. The PRISMA extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses of health care interventions: checklist and explanations. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:777–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. ; PRISMA-P Group Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009;339:b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Andreasen NC. Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS). Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1989;17:173–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Rosen JL, et al. Prodromal assessment with the structured interview for prodromal syndromes and the scale of prodromal symptoms: predictive validity, interrater reliability, and training to reliability. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29:703–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Higgins JPT, Green S.. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Chichester, England: Wiley; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Boyle MA, Samaha AL, Rodewald AM, Hoffmann AN. Evaluation of the reliability and validity of GraphClick as a data extraction program. Comput Human Behav 2013;29:1023–1027. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P.. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-analyses. Ottawa, Canada: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Puhan MA, Schünemann HJ, Murad MH, et al. A GRADE Working Group approach for rating the quality of treatment effect estimates from network meta-analysis. BMJ 2014;349:g5630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Higgins JPT, Green S, Scholten RJPM. Maintaining reviews: updates, amendments and feedback. In: Julian Higgins and Sally Green, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2008:31–49. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Woods SW, Walsh BC, Hawkins KA, et al. Glycine treatment of the risk syndrome for psychosis: report of two pilot studies. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;23:931–940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Javitt DC, Zukin SR. Recent advances in the phencyclidine model of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:1301–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Collaboration C. Review manager (RevMan) [computer program]: Version; Copenhagen, Denmark: The Nordic Cochrane Centre; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dunlap WP, Cortina JM, Vaslow JB, Burke MJ.. Meta-analysis of Experiments with Matched Groups or Repeated Measures Designs. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Becker LA. Effect Size (ES). Colorado Springs: University of Colorado Colorado Springs; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dias S, Sutton AJ, Ades AE, Welton NJ. Evidence synthesis for decision making 2: a generalized linear modeling framework for pairwise and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Med Decis Making. 2013;33:607–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Caldwell DM, Ades AE, Higgins JP. Simultaneous comparison of multiple treatments: combining direct and indirect evidence. BMJ. 2005;331:897–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bucher HC, Guyatt GH, Griffith LE, Walter SD. The results of direct and indirect treatment comparisons in meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:683–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cipriani A, Higgins JP, Geddes JR, Salanti G. Conceptual and technical challenges in network meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:130–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Salanti G. Indirect and mixed-treatment comparison, network, or multiple-treatments meta-analysis: many names, many benefits, many concerns for the next generation evidence synthesis tool. Res Synth Methods. 2012;3:80–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Jansen JP, Naci H. Is network meta-analysis as valid as standard pairwise meta-analysis? It all depends on the distribution of effect modifiers. BMC Med. 2013;11:159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cates C. Maintenance treatment for adults with chronic asthma. BMJ 2014;348:g3148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chaimani A, Higgins JP, Mavridis D, Spyridonos P, Salanti G. Graphical tools for network meta-analysis in STATA. PLoS One. 2013;8:e76654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Dias S, Welton NJ, Sutton AJ, Caldwell DM, Lu G, Ades AE. Evidence synthesis for decision making 4: inconsistency in networks of evidence based on randomized controlled trials. Med Decis Making. 2013;33:641–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Veroniki AA, Vasiliadis HS, Higgins JP, Salanti G. Evaluation of inconsistency in networks of interventions. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:332–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Song F, Altman DG, Glenny AM, Deeks JJ. Validity of indirect comparison for estimating efficacy of competing interventions: empirical evidence from published meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;326:472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; 1988:20–26. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Woods S, Saksa J, Compton M, et al. 112. Effects of ziprasidone versus placebo in patients at clinical high risk for psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2017;43(suppl 1):S58–S58. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Woods SW, Tully EM, Walsh BC, et al. Aripiprazole in the treatment of the psychosis prodrome: an open-label pilot study. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2007;51:s96–s101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Piskulic D, Barbato M, Addington J. Effects of cognitive remediation on cognition in young people at clinical high risk of psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2012;136:S245–S246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Miklowitz DJ, O’Brien MP, Schlosser DA, et al. Family-focused treatment for adolescents and young adults at high risk for psychosis: results of a randomized trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53:848–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. McGlashan TH, Zipursky RB, Perkins D, et al. Randomized, double-blind trial of olanzapine versus placebo in patients prodromally symptomatic for psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:790–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. McFarlane WR, Levin B, Travis L, et al. Clinical and functional outcomes after 2 years in the early detection and intervention for the prevention of psychosis multisite effectiveness trial. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41:30–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Loewy R, Fisher M, Schlosser DA, et al. Intensive auditory cognitive training improves verbal memory in adolescents and young adults at clinical high risk for psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42(suppl 1):S118–S126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Landa Y, Mueser KT, Wyka KE, et al. Development of a group and family-based cognitive behavioural therapy program for youth at risk for psychosis. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2016;10:511–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kantrowitz JT, Woods SW, Petkova E, et al. D-serine for the treatment of negative symptoms in individuals at clinical high risk of schizophrenia: a pilot, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised parallel group mechanistic proof-of-concept trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2:403–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hooker CI, Carol EE, Eisenstein TJ, et al. A pilot study of cognitive training in clinical high risk for psychosis: initial evidence of cognitive benefit. Schizophr Res. 2014;157:314–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Choi J, Corcoran CM, Fiszdon JM, et al. Pupillometer-based neurofeedback cognitive training to improve processing speed and social functioning in individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2017;40:33–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Cadenhead K, Addington J, Cannon T, et al. 23. Omega-3 fatty acid versus placebo in a clinical high-risk sample from the North American Prodrome Longitudinal Studies (NAPLS) Consortium. Schizophr Bull. 2017;43(suppl 1):S16–S16. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Addington J, Epstein I, Liu L, French P, Boydell KM, Zipursky RB. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for individuals at clinical high risk of psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2011;125:54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Amminger GP, Schäfer MR, Papageorgiou K, et al. Long-chain omega-3 fatty acids for indicated prevention of psychotic disorders: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:146–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Cannon TD, Huttunen MO, Dahlström M, Larmo I, Räsänen P, Juriloo A. Antipsychotic drug treatment in the prodromal phase of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1230–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Fusar-Poli P, Frascarelli M, Valmaggia L, et al. Antidepressant, antipsychotic and psychological interventions in subjects at high clinical risk for psychosis: OASIS 6-year naturalistic study. Psychol Med. 2015;45:1327–1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Ising HK, Kraan TC, Rietdijk J, et al. Four-year follow-up of cognitive behavioral therapy in persons at ultra-high risk for developing psychosis: the Dutch Early Detection Intervention Evaluation (EDIE-NL) trial. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42:1243–1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Nordentoft M, Thorup A, Petersen L, et al. Transition rates from schizotypal disorder to psychotic disorder for first-contact patients included in the OPUS trial. A randomized clinical trial of integrated treatment and standard treatment. Schizophr Res. 2006;83:29–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Rauchensteiner S, Kawohl W, Ozgurdal S, et al. Test-performance after cognitive training in persons at risk mental state of schizophrenia and patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2011;185:334–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Ruhrmann S, Bechdolf A, Kühn KU, et al. ; LIPS study group Acute effects of treatment for prodromal symptoms for people putatively in a late initial prodromal state of psychosis. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2007;51:s88–s95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Wessels H, Wagner M, Frommann I, et al. Neuropsychological functioning as a predictor of treatment response to psychoeducational, cognitive behavioral therapy in people at clinical high risk of first episode psychosis. Psychiatr Prax. 2015;42:313–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Urben S, Pihet S, Jaugey L, Halfon O, Holzer L. A randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of a computer-assisted cognitive remediation (CACR) program in adolescents with psychosis or at high risk of psychosis: short term and long term outcomes. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2012;6:41. [Google Scholar]

- 76. McGorry PD, Yung AR, Phillips LJ, et al. Randomized controlled trial of interventions designed to reduce the risk of progression to first-episode psychosis in a clinical sample with subthreshold symptoms. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:921–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. McGorry PD, Nelson B, Phillips LJ, et al. Randomized controlled trial of interventions for young people at ultra-high risk of psychosis: twelve-month outcome. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74:349–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Berger GE, Wood SJ, Ross M, et al. Neuroprotective effects of low-dose lithium in individuals at ultra-high risk for psychosis. A longitudinal MRI/MRS study. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18:570–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. McGorry PD, Nelson B, Markulev C, et al. Effect of ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in young people at ultrahigh risk for psychotic disorders: the NEURAPRO randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74:19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Kobayashi H, Morita K, Takeshi K, et al. Effects of aripiprazole on insight and subjective experience in individuals with an at-risk mental state. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;29:421–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Liu CC, Chien YL, Hsieh MH, Hwang TJ, Hwu HG, Liu CM. Aripiprazole for drug-naive or antipsychotic-short-exposure subjects at putatively prodromal or early state of psychosis: an open-label study. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2012;6:101. [Google Scholar]

- 82. Washida K, Takeda T, Habara T, Sato S, Oka T, Tanaka M, Yoshimura Y, Aoki S. Efficacy of second-generation antipsychotics in patients at ultra-high risk and those with first-episode or multi-episode schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:861–868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Tsujino N, Nemoto T, Morita K, Katagiri N, Ito S, Mizuno M. Long-term efficacy and tolerability of perospirone for young help-seeking people at clinical high risk: a preliminary open trial. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2013;11:132–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. von Hippel PT. The heterogeneity statistic I(2) can be biased in small meta-analyses. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2015;15:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Kumar S, Chaudhury S. Efficacy of amisulpride and olanzapine for negative symptoms and cognitive impairments: an open-label clinical study. Ind Psychiatry J. 2014;23:27–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Danion J-M, Rein W, Fleurot O; the Amisulpride Study Group Improvement of schizophrenic patients with primary negative symptoms treated with amisulpride. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:610–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Kim JS, Kornhuber HH, Schmid-Burgk W, Holzmüller B. Low cerebrospinal fluid glutamate in schizophrenic patients and a new hypothesis on schizophrenia. Neurosci Lett. 1980;20:379–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Heresco-Levy U, Javitt DC, Ermilov M, Mordel C, Silipo G, Lichtenstein M. Efficacy of high-dose glycine in the treatment of enduring negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Leon AC, Davis LL, Kraemer HC. The role and interpretation of pilot studies in clinical research. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45:626–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Miyake N, Miyamoto S, Yamashita Y, Ninomiya Y, Tenjin T, Yamaguchi N. Effects of N-acetylcysteine on cognitive functions in subjects with an at-risk mental state: a case series. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2016;36:87–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Sommer IE, Bearden CE, van Dellen E, et al. Early interventions in risk groups for schizophrenia: what are we waiting for?NPJ Schizophr. 2016;2:16003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Marder SR, Daniel DG, Alphs L, Awad AG, Keefe RS. Methodological issues in negative symptom trials. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37:250–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Kirkpatrick B, Fenton WS, Carpenter WT Jr, Marder SR. The NIMH-MATRICS consensus statement on negative symptoms. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32:214–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Pelletier-Baldelli A, Strauss GP, Visser KH, Mittal VA. Initial development and preliminary psychometric properties of the Prodromal Inventory of Negative Symptoms (PINS). Schizophr Res. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2017.01.055. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Corcoran CM, Kimhy D, Parrilla-Escobar MA, et al. The relationship of social function to depressive and negative symptoms in individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis. Psychol Med. 2011;41:251–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Dong C, Hashimoto K. Early intervention for psychosis with N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor modulators. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2015;13:328–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Woods SW, Kantrowitz JT, Javitt DC. NMDAR-based treatments for patients at clinical high risk for psychosis. Biol Psychiatry. 2014;1:11S. [Google Scholar]

- 98. Yung AR, Woods SW, Ruhrmann S, et al. Whither the attenuated psychosis syndrome?Schizophr Bull. 2012;38: 1130–1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.