Drug overdose accounted for 52 404 deaths in the United States in 2015,1 which are more deaths than for AIDS at its peak in 1995. Provisional data from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) indicate drug overdose deaths increased again from 2015 to 2016 by more than 20% (from 52 898 deaths in the year ending in January 2016 to 64 070 deaths in the year ending in January 2017).2 Increases are greatest forover-doses related to the category including illicitly manufactured fentanyl (ie, synthetic opioids excluding methadone), which more than doubled, accounting for more than 20 000 overdose deaths in 2016 vs less than 10 000 deaths in 2015. This difference is enough to account for nearly all the increase in drug overdose deaths from 2015 to 2016.2

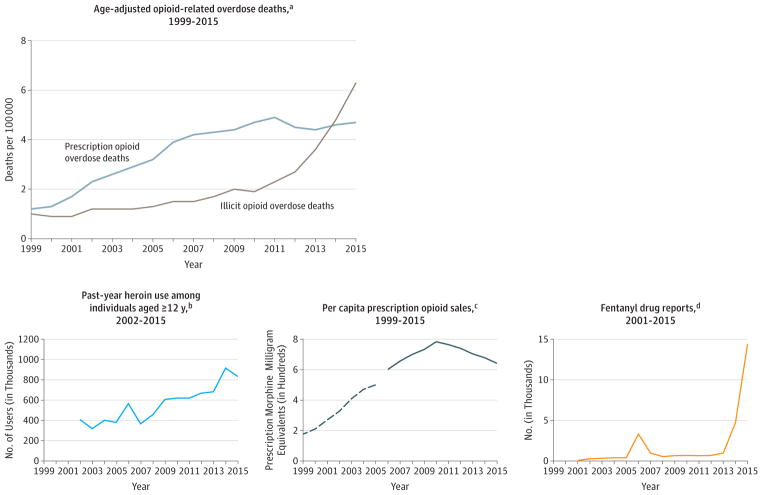

Since 2010, overdose deaths involving predominantly illicit opioids (heroin, synthetic nonmethadone opioids, or both) have increased by more than 200% (Figure). Why have overdose deaths related to illicit opioids increased so substantially? Data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health reveal moderate increases in people reporting past-year heroin use from 2010 to 2015 (Figure). Increasing numbers of individuals who use heroin are younger, might be less experienced, and might use heroin in riskier ways that are difficult to measure (eg, using it alone, using more heroin, using it more often, or combining drugs).

Figure. Opioid Use and Overdose and Fentanyl Drug Reports, 1999–2015.

aSource: National Center for Health Statistics at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. WONDER online database: prescription opioid overdose deaths include fatal overdoses related to natural and semisynthetic opioids or methadone. Illicit opioid-related overdose deaths are related to heroin or synthetic nonmethadone opioids, and some overdose deaths are related to prescribed fentanyl or other prescribed synthetic opioids.

bSource: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Survey on Drug Use and Health. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/population-data-nsduh/reports?tab=38.

c Sources: Dashed line from 1999 to 2005 (Drug Enforcement Administration. Automation of Reports and Consolidated Orders System: sales to pharmacies, hospitals, and practitioners for codeine, fentanyl, hydrocodone, hydromorphone, meperidine, methadone, morphine, and oxycodone. Paulozzi LJ, et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:1487–1492). Solid line from 2006 to 2015 (QuintilesIMS estimates of opioid prescriptions dispensed in the United States to 59 000 pharmacies, representing 88% of US prescriptions. Guy GP Jr, et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:697–704).

dSource: Drug Enforcement Administration. Fentanyl, 2001–2015. https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/nflis/2017fentanyl.pdf. The number of fentanyl drug reports reflects the number of encounters by law enforcement that tested positive for fentanyl. Therefore, fentanyl drug reports provide an indication of the available supply of illicitly manufactured fentanyl.

Although increased heroin use and risk taking likely contribute, available data suggest contamination of the heroin supply with illicitly manufactured fentanyl as the overwhelming driver of the recent increases in opioid-related overdose deaths. Illicitly manufactured fentanyl is usually added to or sold as heroin. For every individual using heroin during recent years in the United States, it is likely that the risk of overdose death has increased considerably.

Fentanyl is approximately 50 times as potent as heroin. This provides strong economic incentives for drug dealers to mix fentanyl with heroin and other drugs because smaller volumes can provide equally powerful effects with lower costs and easier transport. Many people who use heroin are not seeking fentanyl and try to avoid it.3 It can be difficult to identify fentanyl, particularly in the white powder heroin typically sold in states east of the Mississippi River.4 The black tar and brown powder heroin typically sold in Western states might be limiting the penetration of fentanyl into this market for now. Among jurisdictions reporting provisional 2016 data, increases in drug overdose deaths since 2015 were much greater east of the Mississippi River.2

There are limited data about the effectiveness of interventions to prevent overdoses related to illicitly manufactured fentanyl. However, interventions that reduce opioid use disorder and opioid overdoses are likely to reduce overdoses related to illicitly manufactured fentanyl. Unnecessary exposure to prescription opioids must be reduced to prevent development of opioid use disorder in the first place. Despite recent progress, 3 times the amount of opioids were prescribed in 2015 compared with 1999 (Figure). Among people ultimately entering treatment for opioid use disorder, the proportion starting with prescription opioids rather than heroin has decreased in 1 study5 from more than 90% in 2005 to 67% in 2015. However, prescription opioid exposure remains a path to heroin use.

Clinicians need to identify and engage individual patients in offices, clinics, and emergency departments who are in need of and ready for effective opioid use disorder treatment, and offer or arrange medication-assisted treatment. The ability to treat opioid use disorder should become a routine part of medical care, with expectations that all practices have adequate capacity to provide effective treatment. Treatment should be available for patients with opioid use disorder and at risk for overdose, starting with those who survive a drug overdose.

Emergency department protocols could be developed to provide buprenorphine induction and short-duration buprenorphine prescriptions to bridge to longer-term treatment.6 Patient navigators could support linkage to treatment. Collaboration with law enforcement is necessary to link preventive services and effective treatment. For example, providing medication-assisted treatment in prisons increases the probability that incarcerated persons with opioid use disorder, who are at high risk of overdose after release, will engage with treatment after release.7 First responders and close associates of people who use drugs need adequate supplies of naloxone and training to reverse opioid overdose, so those who overdose can be kept alive and have a chance to start treatment.

Near real-time data are needed to drive rapid, coordinated community responses to increases in opioid overdoses. The CDC is working with 32 states and the District of Columbia to improve use of syndromic surveillance and emergency medical services data and identify increases in overdoses more quickly.

Patients and communities must be educated about the risks of opioid use. People with opioid use disorder and their families need to know about evidence-based treatment, so that resources and lives are not squandered pursuing ineffective or harmful therapies. People who use drugs require education about the risks of fentanyl contamination in heroin and other drugs, including cocaine and counterfeit prescription opioids. In most areas of the United States (excluding some Western states for now), people who use heroin should assume the local supply is contaminated with fentanyl. The safest strategy is to avoid exposure to heroin and seek effective treatment. People who are unable to do this can reduce risk by avoiding use while alone, and making sure associates have and know how to use naloxone.

The current opioid crisis has evolved over the past 2 decades and is unlikely to be resolved soon. Opioid use and abuse has taken the lives of hundreds of thousands of people in the United States and is likely to adversely affect and end many more lives. Concerted, multifaceted action, including reducing exposure to illicitly manufactured fentanyl, will be necessary to reduce the catastrophic toll of opioid-related deaths.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: The authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and none were reported.

Disclaimer: The conclusions are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Contributor Information

Deborah Dowell, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia.

Rita K. Noonan, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia.

Debra Houry, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia.

References

- 1.Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, Scholl L. Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(5051):1445–1452. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm655051e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed August 12, 2017];Provisional counts of drug overdose deaths as of August 6, 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/health_policy/monthly-drug-overdose-death-estimates.pdf.

- 3.Carroll JJ, Marshall BDL, Rich JD, Green TC. Exposure to fentanyl-contaminated heroin and overdose risk among illicit opioid users in Rhode Island. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;46:136–145. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gladden RM, Martinez P, Seth P. Fentanyl law enforcement submissions and increases in synthetic opioid-involved overdose deaths. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(33):837–843. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6533a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cicero TJ, Ellis MS, Kasper ZA. Increased use of heroin as an initiating opioid of abuse. Addict Behav. 2017;74:63–66. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D’Onofrio G, O’Connor PG, Pantalon MV, et al. Emergency department-initiated buprenorphine/naloxone treatment for opioid dependence. JAMA. 2015;313(16):1636–1644. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.3474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gordon MS, Kinlock TW, Schwartz RP, et al. A randomized controlled trial of prison-initiated buprenorphine. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;142:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]