Abstract

The extracellular regulated kinases ERK1 and ERK2 are evolutionarily conserved, ubiquitous serine-threonine kinases that are involved in regulating cellular signaling in both normal and pathological conditions. Their expression is critical for development and their hyperactivation is a major factor in cancer development and progression. Since their discovery as one of the major signaling mediators activated by mitogens and Ras mutation, we have learned much about their regulation, including their activation, binding partners and substrates. In this review, I will discuss some of what has been discovered about the members of the Ras to ERK pathway, including regulation of their activation by growth factors and cell adhesion pathways. Looking downstream of ERK activation, I will also highlight some of the many ERK substrates that have been discovered, including those involved in feedback regulation, cell migration, and cell cycle progression through the control of transcription, pre-mRNA splicing and protein synthesis.

Keywords: ERK, Ras, Raf, MEK, Signaling, Adhesion, Feedback, Proliferation, Substrates

1. Introduction

Intracellular signaling is an important mechanism by which cells can respond to their environment and extracellular cues. Cells can sense their environment and modify gene expression, mRNA splicing, protein expression and protein modifications in order to respond to these extracellular cues. Many of these intracellular signaling pathways are affected by activation of some form of extracellular receptor, including receptor tyrosine kinases, cytokine receptors, G protein coupled receptors and adhesion receptors, among others. Changes at the cell surface in receptor expression or mutation, as well as ligand abundance can have profound effects on signals that are transferred throughout the cytoplasm into the nucleus. In disease states such as cancer signaling pathways that stimulate cell proliferation and migration can be hyperactivated, while pathways that inhibit proliferation or signal apoptosis can be lost. Much of the increase in signaling from cell surface receptors in cancer cells comes from receptor tyrosine kinases, which upon activation with a ligand or mutation, dimerize and autophosphorylate or tyrosine residues. These phosphorylated tyrosines serve as docking sites for the recruitment of adapter and signaling proteins to the receptor, generating signaling complexes at the plasma membrane and stimulating intracellular signal transduction. Intracellular, membrane-associated tyrosine kinases, such as those of the Janus kinase (JAK) and Src families act downstream of some cell surface receptors to increase signaling from multiple receptor types, enhancing tyrosine phosphorylation of signaling proteins and the formation of signaling complexes. Upon receptor endocytosis, many of these cell surface receptors continue to signal from endosomes and can either be recycled to the cell surface or degraded in lysosomes. Intracellular signaling from the plasma membrane often occurs through the activation of serine-threonine protein kinases that are part of signaling cascades that can activate subsequent kinases or directly target substrates, changing protein conformation and stimulating or inhibiting the function of the substrate. These signaling pathways can have diverse effects on the cell, including promoting the cancerous phenotypes of increased proliferation, migration, invasion, drug resistance and metastasis.

2. Identification of Extracellular-Regulated Kinases

One of the main signaling pathways downstream of RTKs and other cell surface receptors that is involved in stimulating many aspects of the cancer cell phenotype is the Extracellular-Regulated Kinase (ERK) pathway, primarily p44ERK1 and p42ERK2. ERKs are the original members of the larger family of Mitogen Activated Protein kinases (MAP kinases) that include primarily the Jun N-terminal kinases (JNKs), p38, and ERK5 MAP kinases, whose activity is stimulate in response to a variety of factors, including extracellular stimuli and cell stress (Cargnello & Roux, 2011; Hotamisligil & Davis, 2016; Plotnikov, Zehorai, Procaccia, & Seger, 2011; Schaeffer & Weber, 1999; Weston & Davis, 2007). The ERKs were first cloned by Cobb’s lab in 1990 and 1991 (Boulton, Nye, et al., 1991; Boulton, Yancopoulos, et al., 1990). ERKs 1 and 2 had previously observed by many other labs to be proteins that were quickly phosphorylated by a number of extracellular stimuli and viral infection. Studies by Weber and colleagues had observed tyrosine phosphorylation of proteins of 42 and 40 kilodaltons (kDa) upon epidermal growth factor (EGF) or platelet derived growth factor (PDGF) stimulation or Rous sarcoma virus infection of chicken embryo fibroblasts (J. Cooper, Nakamura, Hunter, & Weber, 1983; Nakamura, Martinez, & Weber, 1983) and Hunter’s group similarly showed tyrosine phosphorylation of two proteins around 42 kDa in response to a variety of mitogens in chicken embryo cells and mouse fibroblasts (J. A. Cooper, Sefton, & Hunter, 1984). These proteins were also observed by many other groups to be threonine and tyrosine phosphorylated in response to a variety of extracellular stimuli, particularly EGF and insulin and the protein phosphatase 1 and 2A inhibitor okadaic acid, and to have a microtubule associated serine/threonine kinase activity (Ahn & Krebs, 1990; Ahn, Weiel, Chan, & Krebs, 1990; Boulton, Gregory, & Cobb, 1991; Boulton, Gregory, et al., 1990; Boulton, Nye, et al., 1991; Haystead et al., 1989; Haystead et al., 1990; Kohno & Pouyssegur, 1986; Ray & Sturgill, 1987, 1988). Two additional splice variants of ERK1 have been identified via inclusion of exon 7, which is in frame in some species, resulting in the larger p46ERK1b, which contains a 26 amino acid insertion within a region in the C-terminus of ERK1 and was shown to be differentially expressed and had differential regulation by MEK1 (Yung, Yao, Hanoch, & Seger, 2000). In other species, exon 7 contains a stop codon and results in the smaller, 40 kDa ERK1c, that may regulate golgi fragmentation under certain conditions in cultured cells (Aebersold et al., 2004). Both splice variants are expressed at lower levels and with a more limited tissue distribution than p44ERK1 and appear to play only minor roles in ERK1 biological function.

3. Ras to MAP Kinase Kinases

3.1 Ras Activation at the Plasma Membrane

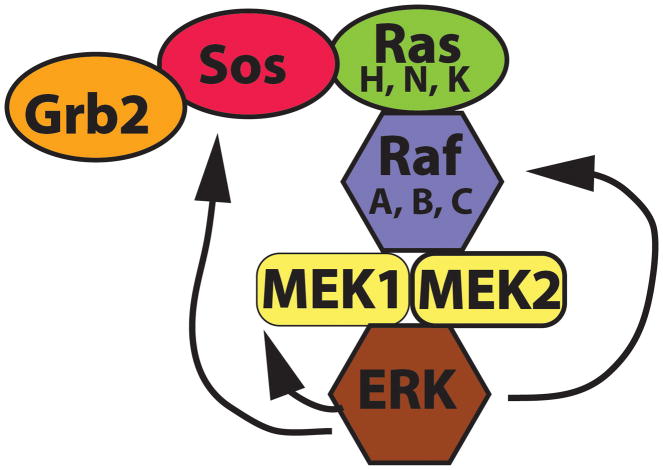

ERKs are rapidly activated after cell stimulation by a number of extracellular stimuli including those which activate receptor tyrosine kinases (Figure 1). Binding of a growth factor to a tyrosine kinase receptor results in receptor dimerization and autophosphorylation on multiple tyrosine residues, generating binding sites for adapter and signaling proteins. One of these adapter proteins is Grb2 (growth factor receptor-bound protein 2), which recruits the Ras guanine nucleotide exchange factor Sos (Son of Sevenless) to activated receptors. The Grb2/Sos complex recruits a member of the Ras family of small GTPases to activated receptors. Ras proteins exist as a superfamily of small GTPases and include the H-Ras (Harvey sarcoma viral oncogene), K-Ras (Kirsten sarcoma viral oncogene) and N-Ras (neuroblastoma oncogene) proteins, which signal to the ERK pathway. The Ras superfamily also contains other small GTPases such as the Rho, Rab, Ran and Arf families of proteins, which each contain several members (Colicelli, 2004; Wennerberg, Rossman, & Der, 2005). Each set of Ras family proteins regulates an aspect of cell biology, including signaling, nuclear import, control of the actin cytoskeleton and membrane trafficking, with some of these Ras proteins carrying out their function through downstream activation of protein kinases. I will focus on the action of Ras proteins at the plasma membrane that activate the ERK cascade downstream of receptor tyrosine kinases, that being K-Ras, H-Ras and N-Ras. The K-Ras gene has two splice variants, K-RasA and K-RasB, with K-RasB having higher expression and enzymatic activity. Knockout studies in mice have shown that both H-Ras and N-Ras are not required for overall mouse development, viability or fertility, even when both are knocked out at the same time, although fewer mice than normal survive embryogenesis in the double knockouts (Esteban et al., 2001). These results suggest that K-Ras is the primary Ras gene that is required for normal function in mouse development, although N-Ras may have some role in viability. Initial knockout of K-Ras in mice showed that embryos died between day 12.5 and term and that at day 11.5 they showed motor neuron cell death in the medulla and cervical spinal cord (Koera et al., 1997). Additionally, at day 15.5 these knockout mice had thin ventricular walls. These results demonstrated a role for the entire K-Ras gene for proper heart and neuronal development. However, this study did not take into account the potential differential effects of deletion of K-RasA versus K-RasB. A subsequent study knocked out only K-RasA and found that these mouse displayed normal viability and fertility (Plowman et al., 2003). These results demonstrated an essential role for the K-RasB gene in mouse development.

Figure 1.

Schematic showing the activation of the Ras to ERK pathway by growth factor binding to a receptor tyrosine kinase. Ligand binding induces receptor dimerization and autophosphorylation. The Grb2 adapter protein binds to activated receptors and increases association of the guanine nucleotide exchange factor Sos to Ras, resulting in Ras loading of GTP and activation. Ras enhances membrane recruitment and activation of the Raf protein kinases, which activate MEKs, leading to ERK activation. Once activated, ERKs phosphorylate cytoplasmic substrates and translocate to the nucleus to phosphorylate nuclear targets.

In unstimulated cells and quiescent cells, Ras proteins primarily exist in an inactive state at the plasma membrane, bound to GDP (guanosine diphosphate), having hydrolyzed the gamma phosphate off of GTP from a previous state of protein activation. In order to achieve membrane localization, which is necessary for Ras proteins to become activated and signal, Ras proteins undergo a complex series of post-translational modifications that increase their hydrophobicity, allowing them to associate with the lipid bilayer. Ras proteins are synthesized with a CAAX motif at the C-terminus, where C is cysteine, A is an aliphatic amino acid and X is any amino acid at this C-terminal position. This sequence serves as a recognition motif for Ras modification, first by proteolytic cleavage of the AAX sequence by Ras converting enzyme (Rce1). This occurs for all four Ras isoforms mentioned above. These Ras proteins then undergo addition of a 15 carbon farnesyl group by a farnesyltransferase group to the now C-terminal cysteine residue, catalyzed by a farnesyltransferase. This modified cysteine then undergoes methylation by a isoprenylcysteine carboxyl methyltransferase (ICMT). K-RasB undergoes no additional isoprenoid modification and becomes membrane localized with the help of the farnesyl group and a polylysine sequence just N terminal to the terminal cysteine in a region called the hypervariable region that enhances the interaction of K-RasB with anionic phospholipids within membranes. This polylysine domain has been shown to ensure K-RasB membrane binding and is important for its transforming ability (Hancock, Paterson, & Marshall, 1990; Jackson, Li, Buss, Der, & Cochrane, 1994). Mutation of the lysines to arginines, preserving the positive charges of these residues, allowed K-RasB to maintain its full transforming potential in NIH3T3 and Rat-1 cell lines in vitro. Mutation of just two of the six lysines with glutamines reduced K-RasB membrane localization by 10%, but inhibited K-RasB transforming potential by 90%, demonstrating an essential role for this polybasic sequence in K-RasB function (Jackson et al., 1994). H-Ras, N-Ras and K-RasA do not contain the polybasic region of K-RasB and undergo additional modification of a nearby cysteine, which becomes palmitoylated by a palmitoyltransferase, enhancing membrane association. Efforts in drug discovery have sought to inhibit these isoprenoid modifications to Ras proteins, particularly with the development of farnyesyltransferase inhibitors, as this modification is common to all four Ras isoforms. These efforts have been largely unsuccessful due to inhibition of farnesylation stimulating the addition of geranylgeranyl isoprene to Ras in place of farnesylation, allowing for Ras membrane localization and signaling. Some reports have concluded that Ras proteins dimerize upon binding GTP and that this dimerization plays a role in activation of some downstream effectors, including Raf. Structural studies have shown that K-RasB undergoes dimerization upon binding GTP, but is a monomer in its GDP-bound state, and determined the regions involved in dimerization (Muratcioglu et al., 2015). While Ras monomers can bind to Raf, dimerized Ras may help promote the dimerization of Raf (see below), which Is important for Raf activation and subsequent activation of ERK (Freeman, Ritt, & Morrison, 2013; Rajakulendran, Sahmi, Lefrancois, Sicheri, & Therrien, 2009). Since farnesyltransferase inhibitors have proven ineffective in inhibiting Ras signaling, these dimerization interfaces of Ras could be viable targets of therapeutic intervention in order to prevent Ras dimer formation and downstream signaling.

3.2 Ras Activation by Sos

Upon activation of a receptor tyrosine kinase at the membrane and subsequent recruitment of the Grb2/Sos complex, Sos associates with inactive Ras and stimulates the release of GDP from Ras, promoting GTP binding. After binding of GTP, Ras undergoes conformational changes in the Switch I and II domains in the effector lobe of Ras to create a protein-protein interaction surface that then associates with signaling proteins, activating signaling pathways from the plasma membrane and distributing them throughout the cytoplasm and into the nucleus. Ras induces activation of many its primary targets, or effector molecules, by stimulating their recruitment to the plasma membrane, where they undergo conformational changes or activation by additional membrane-associated proteins, often by protein phosphorylation. These downstream effectors include the Raf proteins (discussed below), phospholipase C, phosphoinositide 3-kinase, RalGDS (Ral guanine nucleotide dissociation stimulator) and Tiam1, among others (Rajalingam, Schreck, Rapp, & Albert, 2007).

3.3 Ras Mutational Activation

In cancer cells, enhanced growth factor receptor expression or mutation, or increased ligand abundance can lead to enhanced receptor dimerization and phosphorylation, promoting increased signaling from Ras to its effectors. Naturally-occurring mutations in Ras, particularly at glycine 12, glycine 13 and glutamine 61, inhibit the intrinsic GTPase activity of Ras, resulting in prolonged signaling in the absence of cellular stimulation due to an inability to cleave the gamma phosphate of GTP and return Ras to its basal activation state. Ras mutations occur in 30% of all human cancers and up to 95% in cancers such as pancreatic cancer (Bryant, Mancias, Kimmelman, & Der, 2014). Ras mutations, particularly in K-rasB, act to constitutively upregulate signaling pathways in cancer cells that lead to enhanced proliferation, migration, invasion, metastasis and survival.

3.4 Rafs

One of the main effectors of Ras activation and the primary mediators of downstream signaling to the ERKs is the Raf family of protein kinases: C-Raf (also called Raf-1), B-Raf, and A-Raf. These are serine/threonine kinases whose main role in cells is phosphorylation and activation of the MAP kinase kinases MEK1 and MEK2. Rafs contain regions important for binding to Ras in their N-terminus and a C-terminal kinase domain. Upon activation of Ras, Raf proteins are recruited to the plasma membrane for activation, in part by conformational changes induced by Ras that result in C-Raf and B-Raf heterodimerization (C. K. Weber, Slupsky, Kalmes, & Rapp, 2001) and allow for other proteins to modify the activation of Raf through changes in phosphorylation and interactions with binding proteins. Initial findings suggested that the purpose of Ras in Raf activation was merely for plasma membrane localization, as addition of a CAAX sequence to the C-terminus of C-Raf resulted in full activation of the kinase (Stokoe, Macdonald, Cadwallader, Symons, & Hancock, 1994). In this study, oncogenic K-Ras did not further stimulate Raf-CAAX activation, nor did a dominant-negative form of Ras inhibit its activity. Once recruited to the plasma membrane, Raf-CAAX did not stay there, but was found in the cytoplasm and associated with the cytoskeleton (Stokoe et al., 1994). However, a subsequent study found that Raf association with Ras does enhance Raf-CAAX activation (Mineo, Anderson, & White, 1997). Raf proteins undergo multiple phosphorylations that can either stimulate or inhibit kinase activity, as well as affect binding to associated proteins, including Ras, MEK and 14-3-3 proteins (Dhillon & Kolch, 2002). Two sites whose phosphorylation is required for the kinase activity of C-Raf are Ser338 and Tyr341 (Chaudhary et al., 2000; King et al., 1998; Mason et al., 1999). Ser338 is a reported substrate for PAK1 and PAK3, while Src family kinase overexpression induces phosphorylation of Tyr341. Tyr341 phosphorylation overcomes the autoinhibition of C-Raf activity by its regulatory domain (Chaudhary et al., 2000). Importantly, B-Raf naturally contains a phospho-mimetic aspartate residue at position 448, analogous to Tyr341 in C-Raf, contributing to its enhanced basal kinase activity. In addition, B-Raf mutations within the kinase domain, particularly the V600E mutation, are observed in several human cancers, particularly melanoma, and are active targets for therapeutic intervention (Davies et al., 2002; Turski et al., 2016).

3.5 Mitogen Activated Protein Kinase Kinases (MEKs)

MEK1 and MEK2 are downstream targets of the Rafs and other protein kinases that fall into the Mitogen Activated Protein kinase kinase category. MEK1 and MEK2 are phosphorylated by MAP kinase kinase kinases on two serine residues in their activation loop which correspond to serines 218 and 222 in MEK1 and phosphorylation of both residues is required for full activation of MEK (Alessi et al., 1994). P21 activated kinase-1 (PAK1) phosphorylation of MEK1 on Ser298 acts as a priming phosphorylation in some instances to facilitate Raf phosphorylation and activation of MEK1, particularly during cellular adhesion (see below) (Frost et al., 1997; Slack-Davis et al., 2003) and can also stimulate autophosphorylation of MEK1 on its activating sites (Park, Eblen, & Catling, 2007). MEK1 and MEK2, as well as other MAP kinase kinases that phosphorylate the JNK, p38 and ERK5 pathways, lie in a small group of kinases that can phosphorylate serine/threonine residues as well as tyrosine residues and are known as dual specificity kinases. The only substrates of MEK1 and MEK2 are ERKs 1 and 2, providing enhanced fidelity of signaling through the ERK cascade and preventing co-activation of other MAP kinase family members or other substrates. MEK1 and MEK2 are similar in structure and sequence identity, although MEK1 appears to play a stronger role than MEK2 in activation of ERK in cells. Interestingly, both kinases contain an additional proline rich sequence inserted into the kinase domain between residues 270–307, within kinase subdomains IX and X, that is not found in other kinases within the MAP kinase kinases (Catling, Schaeffer, Reuter, Reddy, & Weber, 1995; Schaeffer et al., 1998). This sequence in MEK1 contains phosphorylation sites not present in MEK2 and has been shown to be necessary for MEK1 to interact with C-Raf and for MEK1 activation in cells. Deletion of the proline rich sequence from mutationally-activated MEK1 makes it unable to transform Rat1 fibroblasts in culture (Catling et al., 1995), suggesting additional roles for this sequence. Phosphorylation of a threonine in this sequence at position 292 enhances the duration of MEK1 activity after serum stimulation. Seeking a functional explanation for differences between MEK1 and MEK2 mediated by this proline rich insert within the kinase domain, Schaeffer et. al. (Schaeffer et al., 1998) performed a two-hybrid screen with MEK1 as bait and identified the first mammalian scaffold protein of the ERK pathway, MP1 (MEK Partner 1). MP1 specifically interacted with the proline rice sequence of MEK1, but not a proline rich sequence deletion mutant or with MEK2 in co-immunoprecipitation experiments. In cells, MP1 enhanced the specific binding and activation of ERK1 with MEK1 and enhanced ERK1 activation of the nuclear substrate Elk1 in a luciferase reporter assay. Increased association or activation of ERK2 with MEK1 was not observed (Schaeffer et al., 1998). MP1 overexpression functionally increased ERK1 activation in response to H-RasV12 (Sharma et al., 2005). Independently, a two-hybrid screen of a protein called p14, which localizes to late endosomes and early lysosomes, identified MP1 as a binding partner of p14 (Wunderlich et al., 2001). Further study showed that p14 recruited signaling complexes containing MEK1, ERK1 and MP1 to endosomal compartments to promote signaling. P14 knockdown inhibited efficient ERK signaling to p90RSK (ribosomal protein S6 kinase) in the cytoplasm and inhibited ERK signaling to an Elk1 luciferase reporter in a dose-dependent manner, corresponding to the extent of p14 knockdown (Teis, Wunderlich, & Huber, 2002).

MEK1 contains three lysine residues just three amino acids in from the N-terminal domain and nearby hydrophobic residues that are required for binding to aspartate and hydrophobic residues in the common docking domain of ERK1 and ERK2, allowing for a direct kinase to substrate interaction (Bardwell, Frankson, & Bardwell, 2009; Tanoue, Adachi, Moriguchi, & Nishida, 2000). These residues are important in holding ERK in the cytoplasm in the absence of cellular or mutagenic stimulation of the pathway, which occurs via the presence of a leucine-rich nuclear export signal in the N-terminus of MEK, from residues 32–44 (Fukuda, Gotoh, Gotoh, & Nishida, 1996). The nuclear export signal accounts for the apparent constitutive localization of MEK in the cytoplasm that was observed in earlier studies (Lenormand et al., 1993). This export signal allows for the cytoplasmic localization of MEK via nuclear export by the CRM1 nuclear export protein, which recognizes leucine rich sequences in proteins and contributes to their removal from the nucleus (Fukuda, Asano, et al., 1997). Mutational disruption of the nuclear export sequence of mutationally-active MEK1 induced morphological changes and greatly enhanced the transforming ability of MEK1 in NIH3T3 cells (Fukuda, Gotoh, Adachi, Gotoh, & Nishida, 1997). Deletion of the nuclear export sequence in catalytically inactive MEK1 results in its nuclear translocation upon serum stimulation, while deletion of the nuclear export sequence in mutationally-activated MEK1 resulted in its constitutive localization to the nucleus, even under serum-free conditions (Jaaro, Rubinfeld, Hanoch, & Seger, 1997). These results provide evidence that upon stimulation of the ERK pathway in cells, activated MEK is also translocated to the nucleus, but quickly exported back to the cytoplasm via its nuclear export signal.

4. ERK1 and ERK2

4.1 ERK Activation by Dual Phosphorylation

ERKs are proline-directed serine-threonine kinases that require a proline at the +1 position relative to the phosphorylation site and substrates often contain a proline at the −2 position relative to the site of phosphorylation, to give a consensus of PXS/TP or simply S/TP, where X is any amino acid (Gonzalez, Raden, & Davis, 1991). Human ERK1 and ERK2 are 87% identical in their primary protein sequences and only 2 kDa different in size, while across mammals ERKs 1 and 2 are 84% identical. ERK1 contains an additional 17 amino acid sequence near the N-terminus and two additional amino acids at the C-terminus. Evolutionarily, one or both forms of ERK, or an ancestral form or ERK, is present in most if not all species, including invertebrates (Busca, Pouyssegur, & Lenormand, 2016) and in mammals the ERKs are ubiquitously expressed. ERKs 1 and 2 are on separate genes encoded on chromosomes 16 and 22, respectively. ERKs are dually phosphorylated by MEK1 and MEK2 on a TEY sequence in the phosphorylation lip corresponding to Thr202 and Tyr204 in ERK1 and Thr183 and Tyr185 in ERK2, stimulating a 1000-fold activation of intrinsic kinase activity (Ahn et al., 1991; Payne et al., 1991). Phosphorylation of ERK by MEK results in conformational changes in both the phosphorylation lip and the P+1 binding pocket, inducing kinase activation (Canagarajah, Khokhlatchev, Cobb, & Goldsmith, 1997). Dual phosphorylation is required for full activity and mutation of either site generates a dominant-negative molecule that can inhibit signaling by binding to MEKs and downstream targets.

4.2 ERK1 Versus ERK2: Who Gets Top Billing?

One of the major questions that has been asked of the kinases is whether they have specific functions within the cell, organism or in human disease, or are they functionally redundant proteins that support each other to carry out common goals. Early studies that performed genetic knockout of ERK2 in mice resulted in embryonic lethality (Hatano et al., 2003; Saba-El-Leil et al., 2003; Yao et al., 2003), while knockout of ERK1 resulted in live births of mice that were fertile and initially only exhibited a deficiency in maturation of CD4CD8 thymocytes (Pages et al., 1999). These strong phenotypic differences suggested that ERK2 may play a more significant role in mouse development or that temporal or quantitative expression of the genes differed during development. ERK2 protein is generally expressed at higher levels than ERK1 levels in most mammalian tissues (Fremin, Saba-El-Leil, Levesque, Ang, & Meloche, 2015). Numerous studies in cells and mice using knockdown and knockout strategies have suggested specific individual biological functions for ERK1 or ERK2 based on observations when one protein or the other is lost. The question of the importance of ERK1 versus ERK2 in cells was expertly addressed in a recent review article that carefully analyzed the data in a number of papers that showed differences on cellular and mouse effects upon loss of expression of either ERK1 or ERK2 (Busca et al., 2016). After careful analysis of these studies, Busca et al. concluded that ERK1 and ERK2 were functionally redundant and that phenotypic effects that were observed upon loss of one gene/protein or the other were due to overall levels of ERK protein and activity in cells and tissues.

4.3 Cytoplasmic Anchors and Nuclear Translocation

Early studies of ERK localization determined that in serum-starved cells, ERK localized primarily in the cytoplasm, but underwent nuclear translocation upon serum or growth factor stimulation (Chen, Sarnecki, & Blenis, 1992; Gonzalez et al., 1993; Lenormand et al., 1993). Ectopic expression of ERK often lead to erroneous nuclear localization in serum-starved cells, owing to ERK’s relatively small size, which allowed for it to enter the nucleus by passive diffusion through the nuclear pore (Fukuda, Gotoh, & Nishida, 1997; Gonzalez et al., 1993). Proteins of around 45 kDa or less can often pass through the nuclear pore by passive diffusion, which is independent of ATP or a nuclear transport protein, such as the importins. This mislocalization of overexpressed ERK in serum-starved cells suggested that when there was overabundant ERK expressed in a cell, mislocalization to the nucleus could be caused by saturation a cytosolic factor that was responsible for cytoplasmic retention of ERK in unstimulated cells. This lead to the discovery of proteins that act as cytoplasmic anchors for ERKs, holding ERKs in the cytoplasm until cellular stimulation and ERK activation by phosphorylation (Brunet et al., 1999; Fukuda, Gotoh, Adachi, et al., 1997; Fukuda, Gotoh, & Nishida, 1997). Co-expression of these proteins with ERK resulted in cytoplasmic retention of ERK in the unstimulated state and nuclear translocation upon cellular stimulation. These proteins include the ERK activator MEK (Fukuda, Gotoh, & Nishida, 1997) and MAP kinase phosphatase 3 (MKP-3), which can dephosphorylate ERKs to inactivate them (Brunet et al., 1999; Karlsson, Mathers, Dickinson, Mandl, & Keyse, 2004). Overexpression of active MKP-3 results in ERK inactivation, while overexpression of a phosphatase inactive mutant of MKP-3 inhibited ERK signaling to nuclear, but not to cytoplasmic substrates (Brunet et al., 1999), demonstrating a clear cytoplasmic anchor function for MKP-3 irrespective of its phosphatase activity. Additionally, inactive ERK has been shown to interact with the actin cytoskeleton via its interaction with the scaffold protein IQGAP1 (IQ Motif Containing GTPase Activating Protein 1), suggesting that the actin cytoskeleton can play a role in cytoplasmic anchoring of ERK (Vetterkind, Poythress, Lin, & Morgan, 2013). IQGAP1 can also recruit B-Raf, MEK1 and MEK2 to actin filaments in order to facilitate ERK activation in response to a cell stimulus (Ren, Li, & Sacks, 2007).

ERKs do not contain a classic nuclear localization or nuclear export sequence that regulates their localization within the cell; however, activation of the pathway stimulates the translocation of ERK to the nucleus through both energy-dependent and independent mechanisms (Adachi, Fukuda, & Nishida, 1999; Ranganathan, Yazicioglu, & Cobb, 2006) and localization between the cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments is a dynamic process (Costa et al., 2006). Phosphorylation of ERK and its potential dimerization (discussed below) are not alone required for nuclear translocation of active ERK in response to cellular stimulation. Along with dual phosphorylation of ERK by MEK, ERK is further dually phosphorylated on an SPS sequence starting at amino acid 244 by casein kinase 2 (CK2), independently of the phosphorylation by MEK (Chuderland, Konson, & Seger, 2008; Plotnikov, Chuderland, Karamansha, Livnah, & Seger, 2011). These latter phosphorylations enhance ERK interaction with importin 7, a nuclear import protein, in response to EGF or TPA and enhance ERK nuclear translocation. Alanine mutation of the SPS phosphorylation sequence in ERK prevents its nuclear accumulation upon TPA stimulation (Chuderland et al., 2008), while mutation of the serines to glutamic acids stimulates nuclear accumulation in the absence of cell stimulation. Schevzov et al. (Schevzov et al., 2015) further showed that the tropomyosin Tm5NM1, which associates with actin filaments, is important for both ERK interaction with importin 7 and ERK nuclear translocation after its phosphorylation by CK2.

ERK retention in the nucleus requires new protein synthesis, as stimulation of nuclear import in the presence of protein synthesis inhibitors inhibits nuclear accumulation of ERK (Lenormand, Brondello, Brunet, & Pouyssegur, 1998). The ERK-specific dual-specificity phosphatase DUSP5 has been shown to be a nuclear anchor and inactivator of ERK, terminating the nuclear ERK signal and regulating the duration of ERK in the nucleus (Kucharska, Rushworth, Staples, Morrice, & Keyse, 2009; Mandl, Slack, & Keyse, 2005; Volmat, Camps, Arkinstall, Pouyssegur, & Lenormand, 2001). Although DUSP5 is a substrate for ERK, ERK regulates the stability of DUSP5 protein through a kinase-independent mechanism. Nuclear export of ERK can be inhibited by leptomycin B (Adachi, Fukuda, & Nishida, 2000), an inhibitor of the Crm1 nuclear export protein. ERK export requires MEK, as co-injection of MEK and ERK protein into the nucleus of cells results in rapid export of both proteins, but co-injection of the ERK-binding fragment of MEK with ERK inhibited ERK export (Adachi et al., 2000).

4.4 To Dimerization or Not to Dimerize?

Khokhlatchev et al. (Khokhlatchev et al., 1998) used microinjection of TEY dually phosphorylated ERK2 to show that dual phosphorylation of ERK was sufficient to induce nuclear translocation, which was enhanced when thiophosphorylated ERK2 was used and was independent of ERK2 kinase activity, the latter of which agreed with previous studies (Gonzalez et al., 1993; Lenormand et al., 1993). Moreover, microinjection of thiophosphorylated ERK2 was also shown to enhance nuclear translocation of coinjected, unphosphorylated ERK2. These and other experiments, including gel filtration and structural analysis, lead to the conclusion that active ERK forms dimers with either active or inactive ERK, favoring the formation of ERK1/ERK1 and ERK2/ERK2 homodimers over heterodimers (Khokhlatchev et al., 1998). Dimerization was shown to occur through association of leucine residues in loop 16 (L16) in the C-terminus of associated ERK2 molecules and through association of a glutamic acid (E343) in this loop with histidine 176 in the phosphorylation lip of the partnering ERK2. However, many studies have failed to observe the dimerization of ERKs, using both purified proteins and fluorescence techniques in cells, including FRET (fluorescence resonance energy transfer) (Burack & Shaw, 2005; Kaoud et al., 2011; Lidke et al., 2010). Adachi and colleagues showed that tyrosine phosphorylation of ERK by MEK is sufficient for release of ERK and that this dissociation is required for ERK nuclear translocation (Adachi et al., 1999). Moreover, they showed that ERK molecules that are deficient in their ability to dimerize can still translocate to the nucleus and that translocation occurs through passive diffusion. They concluded that ERK dimers translocate to the nucleus by active transport and could be inhibited by the nuclear transport inhibitor wheat germ agglutinin or dominant-negative Ran, a Ras family GTPase that regulates active transport of proteins (Adachi et al., 1999). In support of the role of ERK dimers in nuclear translocation, ERK phosphorylation or dimerization mutants did not interact with Tpr, a component of the nuclear pore complex, (Vomastek et al., 2008), that we previously showed was an ERK2 binding partner and substrate (Eblen et al., 2003). Knockdown or overexpression of Tpr inhibited ERK nuclear translocation, suggesting that dimerization and Tpr binding play a role in ERK nuclear translocation (Vomastek et al., 2008). However, Lidke et al. concluded that nuclear translocation of ERK was controlled by the rate of ERK phosphorylation by MEK and not dimerization, as an ERK1 dimerization mutant showed slower kinetics of phosphorylation by MEK, but accumulated in the nucleus proportionally at the same rate as wild-type ERK (Lidke et al., 2010). While ERK signaling to the nucleus has been shown to be required for gene transcription and cell cycle entry (Brunet et al., 1999), recent work has highlighted a requirement for ERK dimers in cytoplasmic, but not nuclear ERK signaling. Casar et al. found that cytoplasmic scaffold proteins and ERK dimerization were important for phosphorylation of ERK cytoplasmic, but not nuclear, substrates and that signaling to these dimer-dependent substrates in the cytoplasm was required for cell proliferation and transformation and the development of tumors in vivo (Casar, Pinto, & Crespo, 2008). Moreover, a small molecule inhibitor of ERK dimerization, but not phosphorylation, inhibited tumor cell proliferation and induced apoptosis in tumors that contained Ras or B-Raf oncogenes, demonstrating a novel class of drugs that could combat tumors driven by these oncogenes (Herrero et al., 2015).

4.5 Regulation of ERK Activation by Cell Adhesion

In order for metastasis of solid tumor cancer cells to occur, cells lose their attachment to the underlying basement membrane and migrate and invade into the surrounding tissue. The acquisition of the ability to grow in an anchorage-independent manner allows cancer cells to enter into the vasculature to metastasize to a distant site, which is one of the hallmarks of cancer cells (Hanahan & Weinberg, 2000, 2011). In normal cells that lose their adherence to a substrate, ERK loses its ability to be activated in response to growth factor stimulation (Lin, Chen, Howe, & Juliano, 1997; Renshaw, Ren, & Schwartz, 1997) apparently as a cellular mechanism to prevent anchorage independent growth. Upon loss of cell anchorage to a substratum, protein kinase A (PKA) becomes activated and phosphorylates PAK, resulting in a decrease in PAK activity. Inhibition of PKA in detached cells results in slower kinetics of FAK dephosphorylation and a slower dissociation of FAK and the focal adhesion protein paxillin (Howe & Juliano, 2000). The requirement for adhesion-dependent activation of ERK can be overcome by the overexpression of either a kinase active mutant of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) (Renshaw, Price, & Schwartz, 1999) or PAK (Howe & Juliano, 2000). MEK and ERK form a direct complex in the cytoplasm of unstimulated, serum starved cells through an interaction between a positively-charged and hydrophobic sequence in the N-terminal domain of MEK that interacts with a double aspartate and hydrophobic sequence in the common docking domain of ERK (Fukuda, Gotoh, Adachi, et al., 1997; Fukuda, Gotoh, & Nishida, 1997). In experiments that were designed to look at the role of the interaction between MEK and ERK in adherent versus detached cells, detached Cos-1 cells showed a loss of the interaction between MEK1 and ERK2, while MEK2/ERK2 interactions remained intact (Eblen, Slack, Weber, & Catling, 2002). Upon replating these cells onto fibronectin, there was a reengagement of MEK1/ERK2 complexes that allowed for activation of ERK. Formation of these complexes required phosphorylation of MEK1 on Ser298 by PAK1, acting downstream of activation of the small GTPase Rac (Eblen et al., 2002), a member of the Rho family of GTPases that regulates lamellipodia formation in cells and stimulates PAK1 activity. Rac1 L61, a mutationally activated form of Rac1, could stimulate the formation of ERK2 with MEK1, but not MEK2, in adherent cells and this increase in binding could be inhibited with a dominant-negative form of PAK1 (Eblen et al., 2002). As stated above, this phosphorylation of MEK1 on Ser298 is also required for MEK1 activation upon cellular adhesion, facilitating the phosphorylation of MEK1 on Ser 218 and 222 by Raf (Slack-Davis et al., 2003). Thus the Rac/PAK signaling pathway acts for an adhesion-dependent sensor for MEK1 activation, acting through PAK1 phosphorylation of MEK1 to stimulate MEK1 phosphorylation by Raf and complex formation with and activation of ERK2.

In cancer cells, the mechanisms that regulate adhesion dependent can be lost, even in the absence of Ras and Raf mutations. In ovarian cancer, Ras and Raf activating mutations are rare in high grade tumors, but occur in approximately two-thirds of low grade tumors and are mutually exclusive events (Ardighieri et al., 2014; Heublein et al., 2013; Singer et al., 2003; Tsang et al., 2013; Wong et al., 2010; Zeppernick et al., 2014). Ovarian cancer metastasis occurs from the sloughing of cells from the ovary or fallopian tubes into the peritoneal cavity, which is often accompanied by the formation of intraperitoneal ascites fluid, where detached cancer cells form small spheroids in order to survive until they can attach to distant sites (Auersperg, Edelson, Mok, Johnson, & Hamilton, 1998; Labidi-Galy et al., 2017). Ascites fluid contains a complex mixture of growth factors and cytokines that can stimulate ERK activation in adherent cells. Despite the lack of Ras and Raf mutations in high grade ovarian cancer, ERK has been shown to be activated in 91% of pleural and peritoneal effusions from ovarian cancer patients (Davidson et al., 2003), suggesting that ovarian cancers, among other cancers, have found mechanisms to overcome the requirement of anchorage dependence for activation of the ERK pathway. In support of this, we showed that in ovarian cancer cell lines there was a high incidence of strong ERK activation when adherent cells lost cell matrix attachment and were put into suspension culture (A. Al-Ayoubi, Tarcsafalvi, Zheng, Sakati, & Eblen, 2008). Activation of ERK in suspended cells followed a slow but sustained kinetics, with full ERK activation not occurring for 3 hours, but was sustained for up to 48 hours in suspended culture. Activation in suspended cells was not due to loss of phosphatase activity towards ERK, as addition of U0126 to suspended cells quickly inhibited the levels of phosphorylated ERK. Instead, enhanced ERK activation in suspended cells was caused by stimulation of an autocrine loop that was independent of both FAK activity and PAK phosphorylation of MEK1 on Ser298. Replating of cells onto fibronectin resulted in a gradual loss of ERK activation (A. Al-Ayoubi et al., 2008), similar to the normal kinetics of ERK activity in non-cancer cells upon replating onto fibronectin after suspension (Eblen et al., 2004; Eblen et al., 2002; Slack-Davis et al., 2003). Even in ovarian cell lines were there was a low requirement for ERK activity for adherent cell proliferation, as judged by proliferation in the presence of the MEK inhibitor U0126, ERK became active with loss of adhesion and addition of U0126 to cells in soft agar strongly inhibited anchorage-independent colony formation (A. Al-Ayoubi et al., 2008). In this case, ERK activation in the loss of cell adhesion was stimulated through a cell autonomous mechanism, as conditioned media from suspended cells was able to activate ERK in adherent cells. In ovarian and other tumors, factors secreted into the tumor microenvironment likely play a role in anchorage-independent ERK activation, promoting cell survival and anchorage-independent growth.

5 ERK Substrates

5.1 Overview of ERK Signaling to Cellular Substrates

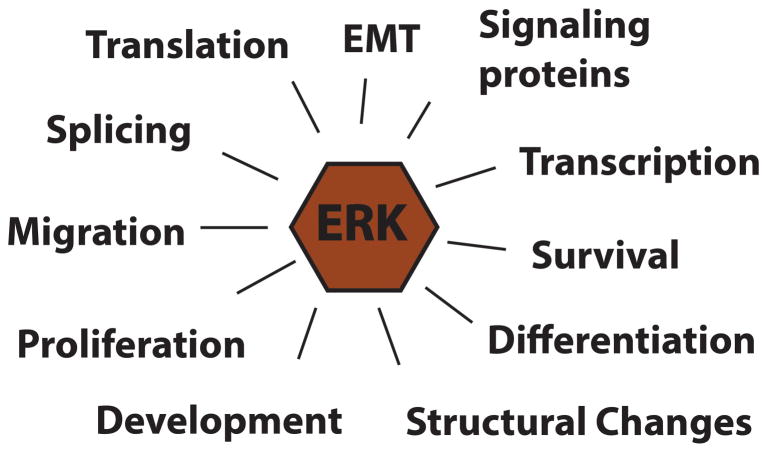

Activation of ERKs occurs within minutes of mitogen activation of the cell and can be constitutively activated by mutational activation of growth factor receptors, Ras or Raf. Since their initial discovery, ERK1 and ERK2 have been shown to phosphorylate a plethora of cellular substrates, with over 250 having been identified through various mechanisms, discussed below, and phosphorylation of these substrates regulates the numerous biological functions that ERKs regulate (Figure 2). Yoon and Segar (Yoon & Seger, 2006), published a comprehensive list of substrates in 2006, but in the past 12 years that list of substrates has grown, due in part through the progress of mass spectrometry techniques that can identify global changes in the phosphoproteome upon activation or inhibition of the ERK pathway. Unal et al. (Unal, Uhlitz, & Bluthgen, 2017) have established an online database of substrates to aid investigators in keeping up with the progress of ERK substrate identification. For the remainder of this article, I will discuss how ERKs have been shown to interact with their substrates, techniques that have been used for substrate identification and discuss how ERK phosphorylation of some specific substrates have been shown to regulate cell signaling and cell function.

Figure 2.

ERK signaling generates multiple biological responses through direct phosphorylation of its protein substrates.

5.2 Substrate Interaction Domains

The association of ERK with its substrates through binding interactions has greatly facilitated the identification and understanding of how ERKs regulate their substrates. ERKs interact with many of their substrates through a DRS (D-site recruitment site) which contains two essential aspartates in the common docking domain (CD domain) and a hydrophobic grove, which interact with positively charged and hydrophobic residues in the KIM (kinase interacting motif) domain of the substrate, activator (i.e. MEK) and phosphatases, as well as the FRS (F-site recruitment site), which interacts with the FXF/FXFP motif in the F-site or DEF (docking site for ERK, FXF) domain of the substrate or binding partner (Bardwell et al., 2009; Burkhard, Chen, & Shapiro, 2011; Fantz, Jacobs, Glossip, & Kornfeld, 2001; Jacobs, Glossip, Xing, Muslin, & Kornfeld, 1999; Lee et al., 2004; Roskoski, 2012; Sheridan, Kong, Parker, Dalby, & Turk, 2008; Tanoue et al., 2000). These two interaction domains in substrates associate with ERK in different ways: the DEF domain binds ERK near the catalytic cleft and the D domain binds on the opposite side of the kinase. Fernandes et al. (Fernandes, Bailey, Vanvranken, & Allbritton, 2007) used substrate peptides to show that addition of a docking site to a peptide enhances the affinity of the peptide for ERK by 200-fold. Careful analysis of protein sequences in putative substrates has been useful in the understanding and characterization of the binding properties of ERK with its substrates, activators such as MEK and phosphatases that serve in inactivate ERK. Some ERK substrates contain one or both of these binding domains, while others contain neither. However, the presence of binding domains in ERK substrates enhances the ability of ERK to phosphorylate the substrate, as mutation of these sites often lowers their phosphorylation by ERK due to loss of enhanced kinase/substrate interactions (Murphy, MacKeigan, & Blenis, 2004; Murphy, Smith, Chen, Fingar, & Blenis, 2002). Individual mutation of the two substrate binding domains in ERK can directly compromise the signaling to a specific set of cellular targets that interact with each domain on ERK (Dimitri, Dowdle, MacKeigan, Blenis, & Murphy, 2005).

5.3 Substrate specificity: Whodunit?

ERKs share their consensus phosphorylation motif, the PXS/TP or S/TP motif, with other members of the MAP kinase family, including the JNKs, p38 and ERK5 MAP kinases. Additionally, other kinases, such, as the cyclin-dependent kinases, are proline-directed kinases as well. The presence of the full consensus sequence can often give insight into the potential presence of an ERK phosphorylation site, but does not mean that a given site is phosphorylated by ERK, or any other MAP kinase. Indeed, some S/TP motifs are in the consensus motifs for other kinases and are phosphorylated based on amino acids that surround the serine or threonine that becomes phosphorylated. Chemical inhibitors for individual MAP kinase pathways and phospho-specific antibodies to an individual site are extremely useful in determining the particular kinase pathway that is inducing phosphorylation of a site after stimulation with a given agonist or activation of a signaling pathway. For example, we identified the alternative splicing factor Rbm17 (RNA binding motif protein 1), also known as SPF45 (splicing factor 45kDa), as a novel substrate of ERK with phosphorylation occurring on Ser222, a residue that fell within a PRSP sequence, and Thr71, which is in a VDTP sequence, without the proline at the −2 position relative to the threonine phosphorylation site (A. M. Al-Ayoubi, Zheng, Liu, Bai, & Eblen, 2012). Phosphorylation of Ser222 of SPF45 was relatively constitutive in cells, but could be induced further by a variety of cellular stimuli in an ERK-dependent manner, whereas Thr71 phosphorylation was absent in resting cells and strongly stimulated by ERK activation. The preponderance of Ser222 phosphorylation could be due to a phosphorylation contribution by another kinase or slow turnover of phosphorylation by phosphatases. In experiments examining the specificity of the phosphorylations by ERK, and not other MAP kinases, we determined through co-immunoprecipitation and in vitro kinase assays that SPF45 was also bound and phosphorylated by JNK and p38. So which one is the true kinase that phosphorylated SPF45? Interestingly, use of chemical inhibitors specific to each kinase pathway and phospho-specific antibodies to the sites revealed that depending on the cellular stimulus, such as H2O2, PMA (phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate), ultraviolet light, and anisomycin, one or more MAP kinase pathways were activated and phosphorylated SPF45 on one or both phosphorylation sites. This study highlights the ability of individual extracellular stimuli to induce phosphorylation of a particular MAP kinase target and how pathway specific inhibitors can allow one to delineate which MAP kinase pathway is targeting an individual substrate under different cellular conditions. This was also the first alternative splicing factor that was shown to be phosphorylated by multiple MAP kinase pathways.

5.4 Substrate Identification Techniques

Since the discovery of the ERK signaling pathway and the recognition of its importance in so many different biological processes, one of the major problems still being addressed is the identification of its cellular substrates and the impact of these phosphorylation events on the protein targets and biological outcomes. Several approaches have been taken to identify ERK substrates. Many substrates have been identified through their association with the ERKs after mitogen stimulation and their changes in migration on one and two-dimensional gels. Other methods of substrate detection have included the use of pharmacological MEK inhibitors, co-immunoprecipitation of ERK-associated proteins and two hybrid screens to identify binding partners (Maekawa, Nishida, & Tanoue, 2002; Waskiewicz, Flynn, Proud, & Cooper, 1997). Additional substrates have been identified by phage display libraries and phosphorylation with recombinant ERK (Fukunaga & Hunter, 1997). We (A. M. Al-Ayoubi et al., 2012; Eblen et al., 2003; Eblen, Kumar, & Weber, 2007; Kumar, Eblen, & Weber, 2004; Zheng, Al-Ayoubi, & Eblen, 2010) and others (Carlson et al., 2011) have used a chemical genetics approach pioneered by Kevan Shokat to utilize an ERK2 engineered with a point mutation in the “gatekeeper” residue (Shah, Liu, Deirmengian, & Shokat, 1997) that can accept unnatural ATP analogues to specifically label and identify novel ERK targets (A. M. Al-Ayoubi et al., 2012; Eblen et al., 2003). This method was expanded by Whites group to utilize a SILAC-based (stable isotype labeling with amino acids in cell culture) proteomic approach for a large scale identification of ERK substrates, identifying 80 potential substrates, only 13 of which were previously known (Carlson et al., 2011). Several groups have also used various proteomic approaches, including shotgun proteomics and IMAC (immobilized metal affinity chromatography) and 2D-DIGE (two-dimensional difference gel electrophoresis) followed by mass spectrometry, often in combination with pharmacological ERK pathway inhibition (Kosako & Motani, 2017; Kosako et al., 2009; Lewis et al., 2000; C. Pan, Olsen, Daub, & Mann, 2009). These global approaches primarily look for changes in overall protein phosphorylation and for sites that have a MAP kinase consensus phosphorylation motif, but verification of these proteins and phosphorylation sites requires further follow-up with experiments that directly address the ability of ERK to phosphorylate the proposed target. However, they also give a good overall view of what is happening globally to the proteome and how changes in ERK signaling affect other proteins, even though some are not direct ERK substrates. Indeed, ERKs phosphorylate and activate other protein kinases, collectively called the MAP kinase-activated kinases, including the p90RSKs, MSKs (mitogen- and stress-activated kinases), MNKs (MAP kinase-interacting kinases) and MKs (MAP kinase-activated protein kinases) (Cargnello & Roux, 2011).

5.5 Feedback Phosphorylation

ERK activation can be transient or sustained, depending upon the cell stimulus. Part of the mechanism for controlling the duration of ERK activation is through inactivation of upstream components of the signaling pathway through direct phosphorylation by ERKs once they become activated (Figure 3). ERK phosphorylates its upstream activator MEK1 on Ser292 and Thr386 to inhibit MEK1 activity (Brunet, Pages, & Pouyssegur, 1994; Mansour et al., 1994) and to decrease the duration of MEK1 activation in newly-adherent cells (Eblen et al., 2004). The latter inactivation occurs through a mechanism involving MEK1 Ser292 phosphorylation in the proline-rich sequence, with the added negative charge of phosphorylation at this site neutralizing a neighboring arginine at position 293. Arg293 of MEK1 lies in a consensus phosphorylation sequence for PAK1, which phosphorylates MEK1 on Ser298 (Eblen et al., 2004; Frost et al., 1997; Slack-Davis et al., 2003), a priming phosphorylation required for activating Raf phosphorylation of MEK1 on serines 218 and 222 during cell adhesion (Slack-Davis et al., 2003).

Figure 3.

Activation of ERK results in negative feedback regulation of pathway activation by direct phosphorylation of upstream components of the pathway, namely MEK1, B-Raf and C-Raf, and Sos.

Additionally, in NIH3T3 cells stimulated with PDGF, C-Raf was phosphorylated on serines 29, 43, 289, 296, 301 and 642 in a MEK-dependent manner, with all but Ser43, which is not in a serine-proline sequence, being phosphorylated by ERK (Dougherty et al., 2005). ERK phosphorylation of these sites leads to downregulation of C-Raf activity by inhibiting the Ras/Raf interaction. Alanine mutation of these sites increased C-Raf basal activity and prolonged activation in response to PDGF treatment, demonstrating their role in negative feedback regulation of C-Raf. B-Raf has also been shown to be a target of dual ERK phosphorylation on an SPKTP sequence in the C-terminus in response to B-cell antigen receptor activation in B lymphocytes (Brummer, Naegele, Reth, & Misawa, 2003), where B-Raf has been shown to be the major Raf isoform involved in ERK activation (Brummer, Shaw, Reth, & Misawa, 2002). Mutation of the phosphorylation sites to glutamic acid or aspartic acid inhibited differentiation in PC12 cells, suggesting that these sites are important feedback regulation sites that inhibit Raf activity (Brummer et al., 2003). Morrison’s group further showed that B-Raf is phosphorylated by ERK on 4 residues and that this phosphorylation disrupts the heterodimerization of B-Raf with C-Raf, inhibiting signaling (Ritt, Monson, Specht, & Morrison, 2010). However, feedback phosphorylation on B-Raf by ERK had a greatly-reduced ability to inhibit C-Raf activity from cells expressing high-activity mutants of B-Raf, namely V600E and G469A. These results highlight how some B-Raf mutants can stimulate increased signaling not only through intrinsic increases in kinase activity, but also through evasion of negative feedback loops.

Further upstream on the pathway, ERK phosphorylates the Ras GEF Sos1. Initial studies had shown that Sos1 became phosphorylated in response to growth factor stimulation of cells and ERK was confirmed to phosphorylate some of these sites (Cherniack, Klarlund, & Czech, 1994; Porfiri & McCormick, 1996; Rozakis-Adcock, van der Geer, Mbamalu, & Pawson, 1995), suggesting that Sos1 phosphorylation was a mechanism by which ERK could downregulate signaling from Ras. Further analysis showed that phosphorylation of Sos1 by ERK occurs among the proline-rich SH3 domains in the C-terminal domain of Sos1 on Ser1132, Ser1167, Ser-1178 and Ser1193 (Corbalan-Garcia, Yang, Degenhardt, & Bar-Sagi, 1996), although additional kinases may also play a role in phosphorylation of Sos1 on these sites, as at least one site does not contain a proline at the +1 position. The proline rich sequences play a role in association of Sos1 with the adapter protein Grb2, which binds to phosphorylated tyrosine residues on receptor tyrosine kinases. Alanine mutation of these phosphorylation sites in Sos1 demonstrated that feedback phosphorylation by ERK after serum stimulation inhibited the association of Sos1 with Grb2, suggesting a role for feedback phosphorylation in downregulation of signaling. Other studies have concluded that ERK phosphorylation of Sos1 acts not to decrease the Grb2/Sos1 complex itself, but to decrease its association with Shc and the EGF receptor (Rozakis-Adcock et al., 1995). One or both of these mechanisms may be occurring in any given cell type, but both mechanisms support a role for ERK phosphorylation of Sos1 to decrease signals coming from upstream of ERK, allowing for a downregulation of signals that induce ERK activation. Interestingly, Sos2, which has a higher affinity for Grb2 than does Sos1 (S. S. Yang, Van Aelst, & Bar-Sagi, 1995), only contains one potential ERK phosphorylation site and the Grb2/Sos2 interaction was not affected by serum stimulation (Corbalan-Garcia et al., 1996).

5.6 Signaling to Transcription Factors for Cell Proliferation

Addition of mitogenic factors to quiescent cells induces cell cycle entry and G1 progression, leading to DNA replication and mitosis. Many of these factors result in the translocation to or activation of ERK in the nucleus (Chen et al., 1992; Gonzalez et al., 1993; Lenormand et al., 1993), which is required for cell cycle entry and progression through G1 (Brunet et al., 1999). Once in the nucleus, ERK promotes the transcriptional expression of immediate early genes (IEGs), which are genes whose expression is upregulated within the first 30–60 minutes after growth factor stimulation of quiescent cells. Many of the immediate early genes that ERK upregulates are transcription factors that are required to promote cell cycle progression, driving the transcription of genes such as cyclin D1. Upon entering the nucleus after growth factor or serum stimulation of cells, ERK phosphorylates ETS (E26 transformation-specific) family members such as Elk-1 (Cruzalegui, Cano, & Treisman, 1999; Gille et al., 1995; Price, Rogers, & Treisman, 1995; Whitmarsh, Shore, Sharrocks, & Davis, 1995), which interacts with the serum response factor and integrates mitogen signaling into transcriptional responses, resulting in the transcription of immediate early genes such as c-fos, fra, myc and egr-1 (Murphy et al., 2002). Depending on the cell type and mitogen added, a transient or sustained activation of ERK has been observed, both of which result in induction of immediate early gene transcription, but only sustained ERK activation results in cell proliferation in fibroblasts (Balmanno & Cook, 1999; Cook & McCormick, 1996; Roovers, Davey, Zhu, Bottazzi, & Assoian, 1999; Vouret-Craviari, Van Obberghen-Schilling, Scimeca, Van Obberghen, & Pouyssegur, 1993; J. D. Weber, Raben, Phillips, & Baldassare, 1997). The graded mammalian ERK activation in response to cellular stimuli is converted to a switch-like mechanism to control c-fos induction during the immediate-early gene response (Mackeigan, Murphy, Dimitri, & Blenis, 2005), in part through regulation of ERK nuclear translocation (Shindo et al., 2016). With only transient ERK activation, c-Fos and other IEG protein products are synthesized, but are unstable and quickly become degraded (Murphy et al., 2002). However, with mitogens that induce sustained ERK activation through G1, ERK and p90RSK, an ERK substrate itself (Sturgill, Ray, Erikson, & Maller, 1988), phosphorylate the C-terminus of newly-synthesized c-Fos protein, enhancing c-Fos stability and exposing the DEF domain, which further enhances ERK interaction with c-Fos and c-Fos mediated activity (Murphy et al., 2002). Stabilized c-Fos is then able to induce genes required for G1 progression. Other immediate early transcription factors, such as Myc and Fra, are similarly phosphorylated to enhance their stability and their ability to induce G1 phase genes (Murphy et al., 2002).

ERK can also inhibit negative regulators of cell cycle progression to enhance proliferation and tumorigenesis. Interestingly, ERK signaling through the AP-1 transcriptional complex, both through transcriptional upregulation and phosphorylation, stimulates downregulation of antiproliferative genes that inhibit G1 progression, including sox6, jun-d, gadd45a, and tob1, among others (Yamamoto et al., 2006). Sustained activation of ERK is required throughout G1 to repress these genes, as pharmacological ERK inhibition in mid-G1 results in re-expression of these anti-proliferative genes, inhibiting G1 progression and proliferation. While suppressing tob1 (transducer of erbB2.1) transcription, the Tob1 protein is also a direct ERK target of phosphorylation on Ser152, Ser154, and Ser164 and phosphorylation inhibits Tob1 anti-proliferative function (Maekawa et al., 2002; Suzuki et al., 2002), a requirement for the induction of proliferation and transformation by Ras (Suzuki et al., 2002). Two ways that Tob inhibits proliferation is by acting as a transcriptional co-repressor for cyclin D1 expression and by recruiting the CAF1-CCR4 deadenylation complex to mRNA, although this latter function is ERK phosphorylation-independent (Ezzeddine, Chen, & Shyu, 2012). Another ERK target, the FOXO3a transcription factor, promotes cell cycle arrest by repression of cyclin D (Schmidt et al., 2002) and activation of the cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor p27Kip1 (Dijkers et al., 2000), as well as by activating apoptosis through upregulation of bim and fasL (J. Y. Yang, Xia, & Hu, 2006). Phosphorylation of FOXO3a on serines 294, 344 and 425 by ERK promotes FOXO3a association with the E3 ubiquitin ligase Mdm2, prompting FOXO3a ubiquitination and degradation, thereby removing the growth inhibitory effect of FOXO3a and supporting cell survival and tumorigenesis (J. Y. Yang et al., 2008).

ERK can also inhibit other negative regulators of epithelial cell proliferation, such as signaling from the transforming growth factor beta (TGFb) receptors. TGFb is growth inhibitory to normal epithelial cells; however, oncogenic Ras can often bypass TGFb-mediated growth inhibition (Houck, Michalopoulos, & Strom, 1989; Longstreet, Miller, & Howe, 1992; Valverius et al., 1989). One of the main pathways that the serine-threonine kinase TGFb receptors send anti-proliferative signals is through the SMAD family of transcription factors. TGFb receptors phosphorylate the R-SMADs (receptor-SMADs) to induce their dimerization and heterotrimerization with the co-SMAD SMAD4 and the complex then translocates to the nucleus to regulate gene transcription. Oncogenic Ras, and to a lesser extent EGF, induce ERK phosphorylation of R-SMADs in their linker region, inhibiting R-SMAD nuclear accumulation (Kretzschmar, Doody, Timokhina, & Massague, 1999). Alanine mutation of these phosphorylation sites restores TGFb growth inhibitory responses in Ras transformed cells, demonstrating a direct mechanism for Ras signaling through ERK in the inhibition of TGFb cellular effects.

Positive regulators of cell survival are also directly affected by ERK phosphorylation. The Bcl-2 family protein myeloid leukemia cell 1 (Mcl-1) enhances cell survival and contains a PEST sequence that makes it susceptible to ubiquitination and proteosomal degradation. Mcl-1 is phosphorylated by both ERK (Domina, Smith, & Craig, 2000; Domina, Vrana, Gregory, Hann, & Craig, 2004; Nifoussi et al., 2012) and JNK (Morel, Carlson, White, & Davis, 2009) on Thr 163 in the PEST sequence and phosphorylation by JNK in response to UV light serves as a priming phosphorylation for GSK3b, enhancing Mcl-1 degradation by the proteosome (Morel et al., 2009). However, in cancer cells that have suppressed this degradation pathway, Thr 163 phosphorylation by ERK enhances Mcl-1 stability and cellular resistance to chemotherapeutics such as Ara-C, etoposide, vinblastine and cisplatin (Nifoussi et al., 2012). An isoform of Bim, a pro-apoptotic member of the Bcl2 family, is also a substrate of ERK. There are three splice variants of Bim, with the longest, Bim(EL), acting as a substrate for ERK upon serum withdrawal or activation of Raf-1 (Weston et al., 2003). Serum withdrawal in CC139 lung fibroblasts caused upregulation of bim(EL), which played a role in the induction of apoptosis. Activation of a ΔRaf-1/estrogen receptor chimera with estrogen reduced bim mRNA levels. Additionally, Bim(EL) protein was shown to contain a DEF-type docking domain for ERK and to co-immunoprecipitate with ERK (Ley et al., 2004; Ley, Hadfield, Howes, & Cook, 2005). ERK phosphorylates Bim(EL) and promotes its ubiquitination and proteasome-dependent degradation, thereby inhibiting its pro-apoptotic function.

5.7 ERK Signaling to Focal Adhesions

FAK plays an important role in integrating cell adhesion signals from integrins to affect signaling from growth factors. As mentioned above, cell adhesion is an important determinant in regulating the cellular response to growth factors in normal cells and can be overcome by activated FAK in cells that have lost cell adhesion, allowing them to activate ERK under anchorage independent conditions. Hunger-Glasser and coworkers showed that in response to a variety of cell stimuli, such as bombesin, lysophosphatidic acid, PDGF and EGF, but not insulin, in Swiss 3T3 cells FAK is phosphorylated on Ser910 by ERK (Hunger-Glaser, Fan, Perez-Salazar, & Rozengurt, 2004; Hunger-Glaser, Salazar, Sinnett-Smith, & Rozengurt, 2003). Thus, both factors that signal through receptor tyrosine kinases and G protein coupled receptors signal to FAK through ERK in this manner. Ser-910 phosphorylation in response to PDGF and EGF was regulated independently of the activating Tyr-397 phosphorylation site of FAK in response to these growth factors, which was downstream of PI3-kinase (Hunger-Glaser et al., 2004). Mutation of Ser910 to alanine increased the binding of FAK to the focal adhesion docking protein paxillin, suggesting that ERK phosphorylation of this site may downregulate adhesion signaling in response to growth factor stimulation (Hunger-Glaser et al., 2003). Paxillin itself is also a target for ERK phosphorylation. Stimulation of murine inner medullary collecting duct (mIMCD-3) epithelial cells with hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), an inducer of cell migration in many cell types, induced an ERK dependent band shift in paxillin on western blots, suggesting phosphorylation (Z. X. Liu, Yu, Nickel, Thomas, & Cantley, 2002) and ERK was shown to induce ERK phosphorylation of paxillin at Ser83 (Ishibe, Joly, Liu, & Cantley, 2004; Z. X. Liu et al., 2002). Pretreatment with the MEK inhibitor U0126 before HGF stimulation inhibited ERK and FAK activation. Inhibiting paxillin phosphorylation by ERK or the interaction between paxillin and ERK not only inhibited FAK and Rac activation, but also inhibited cell spreading and migration. These results demonstrate that a major mediator of HGF signaling from the cMet receptor at the cell surface to induce cell migration occurs by signaling of ERK to paxillin in focal adhesions to help bring about FAK and Rac activation as well as focal adhesion turnover. Another study found that in response to a variety of extracellular stimuli, ERK also phosphorylates paxillin on Ser130 and that this phosphorylation acts as a priming event for paxillin phosphorylation on Ser126 (Cai, Li, Vrana, & Schaller, 2006). Phosphorylation of these two sites on paxillin was required for cell spreading, as a double alanine mutant inhibited spreading in paxillin null cells and cell spreading induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in RAW264.7 cells. Moreover, this paxillin mutant slowed neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells in response to nerve growth factor. This study shows additional regulation of ERK in cell spreading through phosphorylation of the focal adhesion protein paxillin.

5.8 Erk Regulation of RNA Processing

Pre-mRNA produced by gene transcription undergoes processing through constitutive and alternative splicing to produce the mature transcripts that are exported to the cytoplasm and translated into protein. Alternative splicing is a major mechanism of generating proteins with differing function from the same gene and approximately 95% of all genes have their message undergo RNA splicing (Q. Pan, Shai, Lee, Frey, & Blencowe, 2008; Wang et al., 2008). Splice-site mutations contribute to approximately 10–15% of the total number of somatic mutations known in cancer and up to 50% of human genetic diseases (Matlin, Clark, & Smith, 2005). Alterations in alternative mRNA splicing factor expression have also been shown in numerous cancers and can strongly influence the apoptotic response (Schwerk & Schulze-Osthoff, 2005). Matter et al (Matter, Herrlich, & Konig, 2002) were the first to show that ERK phosphorylation of splicing factors could affect alternative mRNA splicing. Ras signaling induces the inclusion of exon V of CD44 into mature CD44 transcripts. The RNA binding protein Sam68 (Src-associated in mitosis 68 kDa protein), a member of the STAR (signal transduction activator of RNA) family of RNA binding proteins (Lukong & Richard, 2003), was shown to be required for exon V inclusion and required ERK phosphorylation of Sam68 on Ser58, Thr71 and Thr84 for this effect (Matter et al., 2002). Overall, ERK was found to regulate the phosphorylation of eight residues on Sam68. A key component of cancer cell metastasis is the epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT), which allows cells to lose their cell-cell contacts, to evade anoikis (apoptosis caused by the loss of cell anchorage) and to increase their migratory and invasive potential (Polyak & Weinberg, 2009; Thiery & Sleeman, 2006). Sam68 regulates EMT in colon cancer cells through regulation of an additional splicing regulator, the SF2/ASF proto-oncogene (Valacca et al., 2010). Epithelial-derived signals stimulate ERK phosphorylation of Sam68 and induce changes in the protein levels of SF2/ASF through an alternative splicing-activated nonsense-mediated mRNA decay mechanism. As part of this mechanism, Sam68 was shown to bind directly to the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of SF2/ASF and inhibit splicing of a 3′UTR intron. Mutation of the eight ERK phosphorylation sites on Sam68 affected the ability of Sam68 to modulate SF2/ASF alternative splicing (Valacca et al., 2010). Additionally, Sam68 has been shown to translocate to the cytoplasm in spermatocytes in an ERK-dependent manner, likely involving its direct phosphorylation by ERK, to associate with polysomes and post-transcriptionally regulate a subset of mRNAs involved in spermatogenesis (Paronetto et al., 2006). This serves as an example of how ERK phosphorylation of a single substrate may not only affect alternative splicing, but also protein translation.

As mentioned above, we recently showed that phosphorylation of the alternative splicing factor SPF45 by ERK on Thr71 and Ser222. ERK phosphorylation affected SPF45-dependent exclusion of exon 6 of the pre-mRNA for the fas death receptor, a known SPF45 target (Corsini et al., 2007), in a minigene assay in cells (A. M. Al-Ayoubi et al., 2012). Exon 6 encodes the transmembrane domain of Fas and its exclusion generates a soluble decoy receptor that inhibits Fas/FasL-mediated apoptosis (Cheng et al., 1994). ERK phosphorylation of SPF45 also regulated the incorporation of extra domain A (EDA) region into mature fibronectin mRNA transcripts, regulating cell adhesion to a fibronectin extracellular matrix (A. M. Al-Ayoubi et al., 2012). EDA inclusion occurs less in adult tissues, but is mainly seen in embryonic tissue, fibrotic liver, and wound healing (Blaustein, Pelisch, & Srebrow, 2007), and we have shown that SPF45 overexpression enhances cell migration (Y. Liu et al., 2013). We originally identified SPF45 as an ERK-associated substrate in suspended ovarian cancer cells using a gatekeeper ERK2 mutant, and were able to demonstrate that ERK specifically phosphorylated SPF45 in suspended cells, an action that was inhibited with the MEK inhibitor U0126 (A. M. Al-Ayoubi et al., 2012). Overexpression of SPF45 or a phospho-mimetic mutant of SPF45 inhibited cell proliferation, while cells expressing a double-alanine mutant of SPF45 grew at the same rate as vector control cells, suggesting that ERK phosphorylation of SPF45 slows proliferation. While anti-proliferation is initially counterintuitive in the context of cancer, ovarian cancer multicellular spheroids in intraperitoneal ascites fluid survive in part by slowing their proliferation and upregulating fibronection expression to evade anoikis (Auersperg, Maines-Bandiera, & Dyck, 1997; Casey et al., 2001), both of which were observed with SPF45 overexpression and ERK phosphorylation.

5.9 ERK Regulation of Protein Synthesis

External factors such as nutrients and growth factors regulate the physiological state of the cell and control the production of the factors required for protein synthesis. Increased protein synthesis is an integral part of cellular growth and proliferation and is regulated at many levels, including inactivation of factors that repress the protein synthesis machinery and an increase in the production of ribosomal components and transfer RNAs. The initiation of the protein synthesis machinery is controlled in part by mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) (Gingras, Raught, & Sonenberg, 2001), resulting in phosphorylation of 4EBP1 (4E binding protein 1) and de-repression of translation initiation (Brunn et al., 1997). mTOR activity is upregulated by Rheb (Ras homology enriched in brain), a Ras GTPase superfamily member that acts to promote cell growth (Stocker et al., 2003). Rheb activity is inhibited by binding of the TSC1/TSC2 (tuberous sclerosis) complex, as TSC2 is a GTPase-activating protein (GAP) for Rheb (Garami et al., 2003; Inoki, Li, Xu, & Guan, 2003; Tee, Manning, Roux, Cantley, & Blenis, 2003). Activated ERK binds to TSC2 and phosphorylates it on Ser664, stimulating dissociation of the TSC1/TSC2 complex and removal of its repression of Rheb, resulting in increased cell proliferation and transformation (Ma, Chen, Erdjument-Bromage, Tempst, & Pandolfi, 2005; Saucedo et al., 2003). Moreover, phosphorylation of TSC2 on S664 by ERK has been shown to be a marker for ERK-mediated mTOR activation in human tumors (Ma et al., 2007).

Accompanying an increase in protein synthesis in cells stimulated by mitogens for enhanced G1 progression, there is a parallel need for increased production of ribosomes and transfer RNAs to facilitate the new synthesis of proteins required for an increase in cell size and cell division. Like transcription of mRNA, increased transcription of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) and transfer RNA (tRNA) have been shown to be enhanced by external cues that promote cell growth and proliferation. An increase in rRNA transcription is required for ribosome production and is driven by RNA polymerase I, whose protein levels are relatively unchanged after mitogen stimulation (Zhao, Yuan, Frodin, & Grummt, 2003). Stimulation of serum starved cells with growth factors such as such as EGF, bFGF (basic fibroblast growth factor) and the phorbol ester TPA enhance the transcription of 45S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) through an ERK-dependent pathway and sustained ERK activation is required to maintain rRNA transcription (V. Y. Stefanovsky et al., 2001; Zhao et al., 2003). Two different transcription factors, both of which are ERK targets, have been shown to regulate the induction of pre-rRNA synthesis in response to these mitogens. TIF-1A (transcription initiation factor 1A) binds to the promoter of the 45S rRNA in a complex with RNAPI and other transcription factors, including SL-1, UBF (upstream binding factor) and Myc (Oskarsson & Trumpp, 2005). TIF-1A is phosphorylated by ERK on serines 633 and 649 upon mitogen stimulation and cooperates with these transcription factors to initiate rRNA synthesis (Zhao et al., 2003). Of these two sites, Ser649 shows greater importance; however, both are required for maximal transcriptional activation and prevention of their phosphorylation by mutation or pharmacological inhibitors of the ERK pathway inhibit rRNA transcription. The architectural transcription factor UBF binds to both the 45S rRNA promoter and throughout the 45S gene and regulates both the initiation and elongation steps of rRNA transcription. Its primary role appears to be in elongation by affecting DNA bending and the remodeling of rRNA gene chromatin (V. Y. Stefanovsky, Langlois, Bazett-Jones, Pelletier, & Moss, 2006; V. Y. Stefanovsky et al., 2001). After activation with EGF, ERK phosphorylates UBF on two evolutionarily conserved threonines, 117 and 201, which lie in the DNA binding HMG (high mobility group) boxes 1 and 2. ERK phosphorylation of UBF on these sites negatively regulates the association of UBF with linear DNA. Reversible phosphorylation of UBF by ERK allows UBF to regulate structural elements throughout the rRNA gene, enhancing the ability of RNAPI I to elongate rRNA transcripts (V. Stefanovsky, Langlois, Gagnon-Kugler, Rothblum, & Moss, 2006; V. Y. Stefanovsky et al., 2006; V. Y. Stefanovsky et al., 2001). In addition, tRNA synthesis, which is driven by RNA polymerase III, itself an immediate early gene, is regulated by ERK as well. The BRF1 (B-related factor) subunit of RNA polymerase III is an ERK binding partner and substrate (Felton-Edkins et al., 2003). Inhibition of ERK activation decreases association of BRF1 and RNA pol III with tRNA(Leu) genes. Mutation of BRF1 to prevent ERK binding or phosphorylation inhibits the ability of RNA polymerase III to induce tRNA transcription, demonstrating a critical role for ERK in generating tRNAs for the enhancement of protein synthesis. Overall, these examples demonstrate that ERK regulates the process of cell proliferation multiple levels through direct phosphorylation of its protein targets.

6. Concluding Remarks

Since its initial discovery, we have gained a greater understanding of how the Ras to ERK pathway is regulated, both in terms of normal regulation during development and cellular homeostasis, and in human disease, particularly in multiple forms of cancer. Many downstream substrates of ERK have been identified, giving insight into the specific mechanisms of ERK biological function. Further study of the pathway will aid in the development of novel therapies that can inhibit ERK activation or biological action and overcome the resistance problems associated with many of the current therapies that target the Ras to ERK pathway.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant number 5R01CA187342 from the National Cancer Institute.

References

- Adachi M, Fukuda M, Nishida E. Two co-existing mechanisms for nuclear import of MAP kinase: passive diffusion of a monomer and active transport of a dimer. EMBO J. 1999;18(19):5347–5358. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.19.5347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi M, Fukuda M, Nishida E. Nuclear export of MAP kinase (ERK) involves a MAP kinase kinase (MEK)-dependent active transport mechanism. J Cell Biol. 2000;148(5):849–856. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.5.849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aebersold DM, Shaul YD, Yung Y, Yarom N, Yao Z, Hanoch T, et al. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1c (ERK1c), a novel 42-kilodalton ERK, demonstrates unique modes of regulation, localization, and function. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(22):10000–10015. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.22.10000-10015.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]