Abstract

The Oncology Grand Rounds series is designed to place original reports published in the Journal into clinical context. A case presentation is followed by a description of diagnostic and management challenges, a review of the relevant literature, and a summary of the authors’ suggested management approaches. The goal of this series is to help readers better understand how to apply the results of key studies, including those published in Journal of Clinical Oncology, to patients seen in their own clinical practice.

A 61-year-old man presents with stage II prostate cancer after a period of active surveillance. Work-up reveals T1cN0M0 carcinoma, a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level of 4.8 ng/mL, and Grade Group II (highest Gleason 3+4) in three cores of 12 taken, at the right mid-gland and right apex. The patient has been on active surveillance for the past 16 months. He was originally diagnosed after biopsy for an elevated PSA with stage I prostate cancer, T1cN0M0; PSA, 4.5 ng/mL; Grade Group 1 (Gleason 3+3) in one core of 12 taken, also at the right mid-gland. A multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging scan showed a heterogeneous peripheral zone without a dominant lesion and a calculated prostate volume of 28 mL. His medical history includes hypercholesterolemia, for which he takes atorvastatin. He is otherwise healthy and has no other significant medical or surgical history. His father had prostate cancer in his 70s and died of other causes at 89 years of age. The patient reports 2- to 3-hour urinary frequency and 0 to 1 nocturia, and has no difficulty obtaining or maintaining an erection. After meeting with his urologist, he sees a radiation oncologist.

CHALLENGES IN DIAGNOSIS AND MANAGEMENT

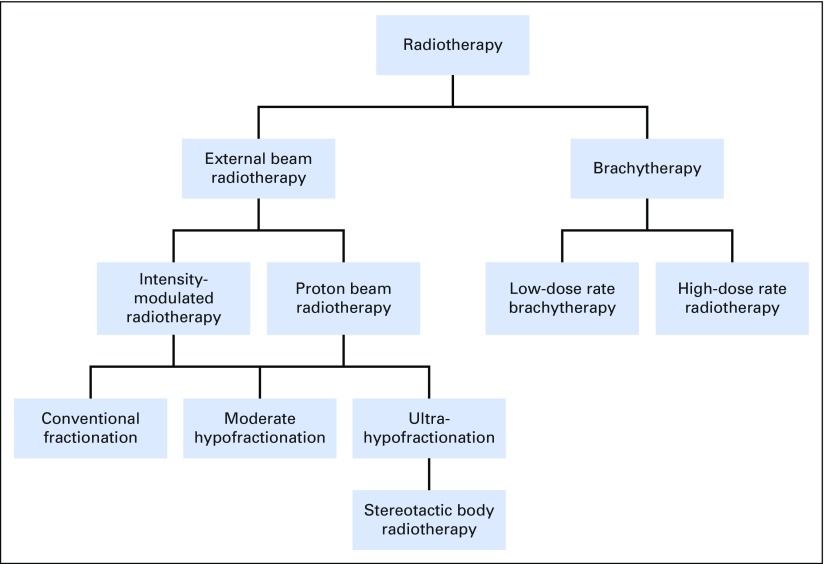

Shared decision making involves helping patients with prostate cancer choose evidence-based treatments that are consistent with their goals of care and preferences for trade-offs between health benefits and harms.1 Shared decision making is crucial in the management of clinically localized prostate cancer, where patients confront a dizzying array of treatment options (Fig 1). They rightfully ask, “Which treatment is right for me?”

Fig 1.

Radiotherapy treatment options for favorable intermediate-risk prostate cancer.

This patient has favorable intermediate-risk, clinically localized prostate cancer, defined as T1c (nonpalpable) disease, Grade Group 2, with PSA < 10 ng/mL. Grade Groups translate Gleason sum 6 to 10 into five categories, increasing in severity from 1 to 5; compared with Gleason sum, Grade Groups more accurately predict PSA recurrence after treatment and are a simpler, more intuitive measure for shared decision making.2,3

Assessment of patient-reported outcomes (PROs) is also essential at the time of diagnosis and during longitudinal follow-up. We use the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite for Clinical Practice (EPIC-CP) questionnaire, which is a 5-minute survey that improves clinic efficiency and fosters individualized attention to baseline urinary, bowel, and sexual function.4,5 The EPIC-CP and the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) also aid in consideration of brachytherapy (BRT), where baseline patient urinary morbidity (IPSS, 15 to 20) and prostate volume (> 60 cm3) are predictive of acute urinary toxicity.6,7 This patient reported an EPIC-CP of 3 out of 60 and an IPSS of 2 out of 35.

Favorable intermediate-risk prostate cancer is highly curable; the 5-year PSA recurrence-free probability is nearly 90%, and prostate cancer mortality at 8 to 10 years is uncommon (1% to 3%) after either surgery or radiation.8,9 This patient is a potential candidate for surgery, external beam radiation with or without short-course androgen suppression, or BRT. For favorable intermediate-risk disease, I would not recommend androgen suppression with external beam radiation, although I would describe to the patient the evidence supporting its use.1,10,11 This patient also remains a candidate for active surveillance, given the absence of findings on his multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging scan, although such an approach may lead to a higher risk of metastatic disease in the long run. Because the primary treatments for prostate cancer have similar efficacy, one way to frame shared decision making is to counsel the patient to choose the treatment that has the side effect profile he is most willing to tolerate.

SUMMARY OF THE RELEVANT LITERATURE

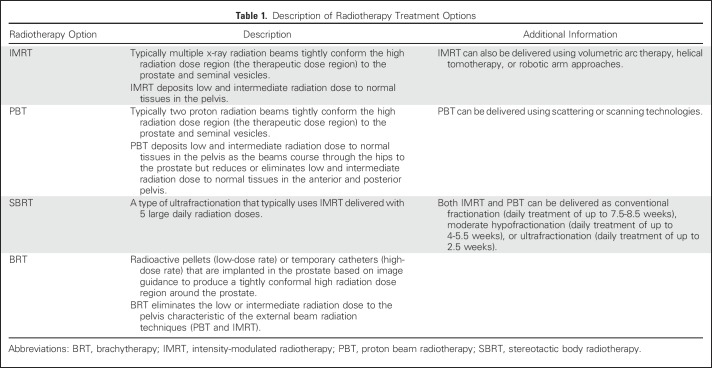

Radiotherapy treatment options for favorable intermediate-risk prostate cancer include external beam radiation, delivered as intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT), proton beam radiotherapy (PBT), stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT), or BRT (Table 1). The essential evidence for shared decision making with patients is the comparative clinical harms—the toxicity profiles for urinary, bowel, and sexual function. In presenting this evidence, I focus to the extent possible on contemporary radiation approaches and findings relevant to men younger than 65 years of age with excellent overall health.

Table 1.

Description of Radiotherapy Treatment Options

URINARY FUNCTION

Urinary dysfunction after radiotherapy involves increased frequency or urgency, pain or burning with urination, or weaker stream. The Prostate Testing for Cancer and Treatment (PROTECT) trial, which randomly assigned men to active surveillance, surgery, or three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy (3DCRT), a precursor to contemporary IMRT, reported PROs through 6 years post-treatment.12 The mean age of participants was 62 years. At 6 months after treatment, radiotherapy caused worse urinary symptoms compared with active surveillance, but, notably, urinary symptoms decreased and were comparable to men who were on active surveillance after 1 year.

North Carolina Prostate Cancer Comparative Effectiveness and Survivorship Study (NCPROCESS), a nonrandomized study of patients (mean age, > 65 years) who received surgery, external beam radiotherapy (mostly image-guided IMRT), BRT, and surveillance, also reported increased symptoms of urinary irritation at 3 months after treatment with IMRT that again resolved at 1 year to levels comparable with surveillance.13 For men with excellent baseline function, nearly five in 10 men retained excellent function at 2 years after IMRT, a similar rate to radical prostatectomy or surveillance. The Comparative Effectiveness Analysis of Surgery and Radiation for Localized Prostate Cancer (CEASAR) trial, a nonrandomized study of patients who received surgery, external beam radiotherapy (again, mostly IMRT), and surveillance, reported no significant difference in urinary symptoms between radiotherapy and surveillance through 3 years; younger patients (mean age, 60 years) did not differ from older patients (mean age, 70 years).14

The available nonrandomized studies of PROs after PBT have not observed substantial differences in urinary adverse effects compared with IMRT. Two studies showed no clinically significant differences in urinary function through 2 years,15 and one study showed minor differences at 1 year that resolved by 2 years.16

The study by Pan et al17 in this issue of Journal of Clinical Oncology analyzes commercial insurance data for patients younger than 65 years and adds to a series of studies using reimbursement claims from Medicare to evaluate radiotherapy treatments for prostate cancer. Administrative claims data lack patient- or clinician-reported outcomes and radiation treatment details. Rather, patients are followed longitudinally by tracking billing codes submitted for reimbursement to payers that map to clinical toxicities. Pan et al17 showed that proton beam was associated with a decrease in billing codes representative of urinary toxicity compared with IMRT at 2 years. This finding is promising but is also a prominent outlier. The three comparative PRO studies of PBT—examining patient-reported symptoms rather than Medicare billing codes—have not shown such a result, nor have the three prior Medicare studies, which reached broadly similar findings on urinary function to the PRO studies.18-20

In terms of BRT, NCPROCESS showed that BRT may have a more pronounced effect on patient-reported urinary symptoms compared with IMRT at 3 months, but these effects resolved by 1 year. However, among those with excellent baseline function, only one in five men retained excellent urinary function at 2 years (although this subgroup contained few patients).

BOWEL FUNCTION

Bowel dysfunction after radiotherapy involves urgency or frequency of bowel movements and rectal bleeding/bloody stools. PROTECT showed that 3DCRT yielded a peak in bowel problems at 6 months that resolved to levels seen among patients on active surveillance over time. Nonetheless, at 6 years, about one in 20 men reported bloody stools half of the time after 3DCRT compared with one in 100 with surveillance.21 With IMRT, NCPROCESS showed a clinically significant difference in bowel problems compared with surveillance in the short term that resolved with longer follow-up. CEASAR also showed that IMRT was associated with clinically meaningful short-term decrements in bowel function compared with surveillance that resolved by year 1; again, younger patients (mean age, 60 years) did not differ from older patients.13

CAESAR specifically evaluated bloody stools, showing no clinically meaningful change in bloody stools between IMRT and surveillance at any time point through 3 years. Bowel dysfunction was rare for patients who received radical prostatectomy. The sum of these data would suggest that IMRT is associated with short-term decrements in patient-reported bowel function that resolve after 1 year and that rectal bleeding is infrequently observed through 3 years. Longer follow-up will determine whether the low rate of rectal bleeding for IMRT shown in CEASAR is durable.14

Two of the nonrandomized studies of PROs after PBT showed a possible reduction of some aspects of short-term bowel dysfunction compared with IMRT that disappears after 1 year.15,16 Another study showed no difference in bowel problems between the two treatments.22 None of the studies showed clinically meaningful differences in overall bowel quality of life or bloody stools between IMRT and proton therapy through 2 years. The Pan et al17 study and other Medicare analyses have shown that PBT compared with IMRT is associated with an increase in billing codes reflecting bowel toxicity.18,19

All of these studies were completed before the clinical introduction of techniques that introduce space between the prostate and the rectum. A randomized trial of one technique, referred to as a biodegradable spacer, versus usual care demonstrated reduced patient-reported clinically meaningful bowel toxicity at 3 years after IMRT.23

For BRT, although an older study of PROs after BRT showed a clinically significant decline in bowel symptoms comparable to 3DCRT,24 NCPROCESS showed that BRT yielded no clinically significant differences in bowel function at any time point compared with men who underwent surveillance through 2 years.13

SEXUAL FUNCTION

Sexual dysfunction after radiotherapy affects the quality and firmness of erections, the ability to reach orgasm, and overall sexual quality of life. NCPROCESS isolated the effect of IMRT without androgen suppression on sexual function for men with excellent baseline sexual function and showed no clinically significant differences in sexual function at any time point compared with active surveillance for men with excellent baseline function. Similarly, CAESAR showed that, among men with excellent baseline sexual function, there was no statistically or clinically significant difference in sexual function at any time point between IMRT without androgen suppression and active surveillance.14

Baseline sexual function is crucial in determining the impact of treatment on subsequent sexual function, regardless of treatment received. For example, among men with erections sufficient for intercourse at baseline, the predicted probability of having erections sufficient for intercourse at 3 years was 73%, 65%, and 44% for active surveillance, IMRT, and nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy, respectively. Among men with erections insufficient for intercourse at baseline, the predicted probability of having erections sufficient for intercourse at 3 years was 19%, 15%, and 6% for active surveillance, IMRT, and nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy, respectively.

For PBT, compared with IMRT, the nonrandomized PRO studies have shown no significant differences in sexual dysfunction.15,16 In terms of BRT, NCPROCESS showed that BRT yielded no clinically significant differences in sexual dysfunction at year 2 compared with men who underwent active surveillance.13

HYPOFRACTIONATION

Although there has been some attention to ultrahypofractionated SBRT compared with IMRT in claims-based analyses of radiotherapy, the more immediate takeaways for current clinical practice focus on moderate hypofractionation (4 to 5 weeks of daily external beam radiation consisting of 20 to 28 treatments) compared with conventional fractionation (8 to 9 weeks of daily external beam radiation). Three multicenter, randomized trials consisting of over 5,500 patients with mostly low- and intermediate-risk prostate cancer have shown that moderate hypofractionation leads to cancer control and bowel, urinary, and sexual function similar to longer radiation treatment courses.25-27 Thus, moderately hypofractionated radiation, which can be delivered with IMRT or PBT, offers curative, safe, and well-tolerated treatment in fewer weeks than the extended radiation courses of the past. The evidence is so compelling that professional societies have convened a joint guideline committee to establish new recommendations for hypofractionated treatment, expected in 2018.

The main concern with SBRT is that the large radiation doses delivered in typically five fractions may interact differently with human tissues than the smaller radiation doses used in lengthier treatment courses, placing patients at risk for long-term unanticipated bowel or urinary toxicity. Pan et al17 provide promising data of similar rates of billing codes for urinary and rectal toxicity between SBRT and IMRT; however, prior studies have shown greater urinary toxicity with SBRT.20,28 Without long-term follow-up of high-quality randomized clinical trials comparing SBRT with hypofractionated or conventional external beam radiation, patients should be cautious when considering SBRT without thorough shared decision making.

OTHER FACTORS

Given the young age of the patient in this case, the potential increased risk of second malignancies after any type of radiotherapy should be considered as part of shared decision making. The absolute increased risk of second malignancies attributable to external beam radiation beyond the baseline risk observed after surgery has been estimated at one in 70 for long-term survivors (> 10 years)29; epidemiologic research suggests that second malignancies attributable to radiation for prostate cancer may be far more rare.30 Although there is a healthy debate, there is no evidence that PBT reduces the rate of secondary malignancies compared with IMRT, especially given the low and intermediate radiation dose exposure to normal tissues in the path of the proton beam. There is evidence that BRT reduces secondary malignancy risk to close to that of surgery, a finding that comports with the tight radiation dose distribution characteristic of this radiation modality.31

The financial toxicity and economic burden of prostate cancer treatments are sizeable. Pan et al17 reported mean radiation expenditures by commercial insurers of $115,501, $59,012, and $49,504 for PBT, IMRT, and SBRT, respectively. In this study, PBT and IMRT were delivered over an average of approximately 8 weeks; we would expect that expenditures for hypofractionated radiation would be less costly. BRT, however, is the least costly of these otherwise equally curative radiation modalities; estimates suggest that BRT is at least one half as costly as IMRT.32,33 Finally, in the event of PSA relapse after radiotherapy, it is important to note that the curative salvage treatment options have the potential for meaningful impact on urinary, bowel, and sexual function.1

SUGGESTED APPROACHES TO MANAGEMENT

Contemporary radiotherapy treatment options are well tolerated, especially in younger men with excellent baseline bowel and genitourinary function. IMRT is the most common form of radiotherapy for prostate cancer in the United States today; the patient in this case is an excellent candidate for moderately hypofractionated radiation. PBT seems to have a similar toxicity profile to IMRT on the basis of PRO studies, but is more costly. Relevant to younger men with longer life expectancy, both types of external beam radiation carry small risks of secondary malignancies > 10 years post-treatment. BRT may have a higher rate of short-term urinary adverse effects but a lower rate of second malignancies and is less costly. All treatment options have high cancer control and prostate cancer–specific survival rates. I would discuss the importance of considering participation in high-quality clinical trials designed to help future patients and the medical community understand the comparative benefits and harms of different treatment modalities for prostate cancer.1 I would also counsel this patient that, regardless of which treatment he decides is right for him, as long as his decision is concordant with his preferences and goals of care, the chances are that he will be satisfied.34

On the basis of consideration of his treatment options with his multidisciplinary care team, the patient chose to move forward with IMRT, and I recommended moderate hypofractionation. He completed treatment in about 5.5 weeks. The urinary irritative symptoms he experienced during treatment resolved to his preradiation baseline by 6 months. Ongoing assessment of EPIC-CP scores revealed no problem or a small problem in the urinary, bowel, and sexual domains. He entered our survivorship program with interval clinic visits, symptom management, and PSA testing for ongoing follow-up.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

I thank the members of the genitourinary malignancies multidisciplinary clinical group at the Abramson Cancer Center at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine for expert insights into the treatment approaches described in this article. I also thank Paul L. Nguyen, MD, Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women's Cancer Center and Harvard Medical School, and Ronald C. Chen, MD, Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel for gracious external peer review of a draft of this article. Paul L. Nguyen and Ronald C. Chen were not compensated for their contribution.

Footnotes

Supported by Grant No. K07-CA163616 from the National Cancer Institute.

See accompanying article on page 1823

AUTHOR’S DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

A Younger Man With Localized Prostate Cancer Asks, “Which Type of Radiation Is Right for Me?”

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/site/ifc.

Justin E. Bekelman

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Sanda MG, Cadeddu JA, Kirkby E, et al. Clinically localized prostate cancer: AUA/ASTRO/SUO guideline. Part I: Risk stratification, shared decision making, and care options. J Urol. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2017.11.095. 10.1016/j.juro.2017.11.095 [epub ahead of print on December 15, 2017] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Epstein JI, Zelefsky MJ, Sjoberg DD, et al. A contemporary prostate cancer grading system: A validated alternative to the Gleason Score. Eur Urol. 2016;69:428–435. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.06.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathieu R, Moschini M, Beyer B, et al. Prognostic value of the new Grade Groups in prostate cancer: A multi-institutional European validation study. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2017;20:197–202. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2016.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang P, Szymanski KM, Dunn RL, et al. Expanded prostate cancer index composite for clinical practice: Development and validation of a practical health related quality of life instrument for use in the routine clinical care of patients with prostate cancer. J Urol. 2011;186:865–872. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.04.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chipman JJ, Sanda MG, Dunn RL, et al. Measuring and predicting prostate cancer related quality of life changes using EPIC for clinical practice. J Urol. 2014;191:638–645. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.09.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamada Y, Rogers L, Demanes DJ, et al. American Brachytherapy Society consensus guidelines for high-dose-rate prostate brachytherapy. Brachytherapy. 2012;11:20–32. doi: 10.1016/j.brachy.2011.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis BJ, Taira AV, Nguyen PL, et al. ACR appropriateness criteria: Permanent source brachytherapy for prostate cancer. Brachytherapy. 2017;16:266–276. doi: 10.1016/j.brachy.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilt TJ, Jones KM, Barry MJ, et al. Follow-up of prostatectomy versus observation for early prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:132–142. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1615869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamdy FC, Donovan JL, Lane JA, et al. 10-year outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1415–1424. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanda MG, Cadeddu JA, Kirkby E, et al. Clinically localized prostate cancer: AUA/ASTRO/SUO Guideline. Part II: Recommended approaches and details of specific care options. J Urol. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2018.01.002. 10.1016/j.juro.2018.01.002 [epub ahead of print on January 10, 2018] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones CU, Hunt D, McGowan DG, et al. Radiotherapy and short-term androgen deprivation for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:107–118. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1012348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donovan JL, Hamdy FC, Lane JA, et al. Patient-reported outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1425–1437. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen RC, Basak R, Meyer AM, et al. Association between choice of radical prostatectomy, external beam radiotherapy, brachytherapy, or active surveillance and patient-reported quality of life among men with localized prostate cancer. JAMA. 2017;317:1141–1150. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barocas DA, Alvarez J, Resnick MJ, et al. Association between radiation therapy, surgery, or observation for localized prostate cancer and patient-reported outcomes after 3 years. JAMA. 2017;317:1126–1140. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoppe BS, Michalski JM, Mendenhall NP, et al. Comparative effectiveness study of patient-reported outcomes after proton therapy or intensity-modulated radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Cancer. 2014;120:1076–1082. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gray PJ, Paly JJ, Yeap BY, et al. Patient-reported outcomes after 3-dimensional conformal, intensity-modulated, or proton beam radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. Cancer. 2013;119:1729–1735. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pan HY, Jiang J, Hoffman KE, et al. Comparative toxicities and cost of intensity-modulated radiotherapy, proton radiation, and stereotactic body radiotherapy among younger men with prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1823–1830. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.75.5371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim S, Shen S, Moore DF, et al. Late gastrointestinal toxicities following radiation therapy for prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2011;60:908–916. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.05.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheets NC, Goldin GH, Meyer AM, et al. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy, proton therapy, or conformal radiation therapy and morbidity and disease control in localized prostate cancer. JAMA. 2012;307:1611–1620. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu JB, Soulos P, Herrin J, et al. Proton versus intensity modulated radiotherapy for prostate cancer: Patterns of care and early toxicity. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:25–32. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donovan JL, Lane JA, Peters TJ, et al. Development of a complex intervention improved randomization and informed consent in a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fang P, Mick R, Deville C, et al. A case-matched study of toxicity outcomes after proton therapy and intensity-modulated radiation therapy for prostate cancer. Cancer. 2014;121:1118–1127. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamstra DA, Mariados N, Sylvester J, et al. Continued benefit to rectal separation for prostate radiation therapy: Final results of a phase III trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2017;97:976–985. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanda MG, Dunn RL, Michalski J, et al. Quality of life and satisfaction with outcome among prostate-cancer survivors. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1250–1261. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dearnaley D, Syndikus I, Mossop H, et al. Conventional versus hypofractionated high-dose intensity-modulated radiotherapy for prostate cancer: 5-year outcomes of the randomised, non-inferiority, phase 3 CHHiP trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:1047–1060. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30102-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee WR, Dignam JJ, Amin MB, et al. Randomized phase III noninferiority study comparing two radiotherapy fractionation schedules in patients with low-risk prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2325–2332. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.0448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Catton CH, Lukka H, Julian JA, et al. A randomized trial of a shorter radiation fractionation schedule for the treatment of localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34 (suppl; abstr 5003) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Halpern JA, Sedrakyan A, Hsu WC, et al. Use, complications, and costs of stereotactic body radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. Cancer. 2016;122:2496–2504. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brenner DJ, Curtis RE, Hall EJ, et al. Second malignancies in prostate carcinoma patients after radiotherapy compared with surgery. Cancer. 2000;88:398–406. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000115)88:2<398::aid-cncr22>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abdel-Wahab M, Reis IM, Hamilton K. Second primary cancer after radiotherapy for prostate cancer--a seer analysis of brachytherapy versus external beam radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;72:58–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berrington de Gonzalez A, Wong J, Kleinerman R, et al. Risk of second cancers according to radiation therapy technique and modality in prostate cancer survivors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;91:295–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.10.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nguyen PL, Gu X, Lipsitz SR, et al. Cost implications of the rapid adoption of newer technologies for treating prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1517–1524. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hayes JH, Barry MJ, McMahon PM. Observation versus initial treatment for prostate cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:574. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-8-201310150-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Strategies for improving patient experience: shared decision making. agency for healthcare research and quality. https://www.ahrq.gov/cahps/quality-improvement/improvement-guide/6-strategies-for-improving/communication/strategy6i-shared-decisionmaking.html#6i3.