Abstract

The increasing prevalence and severity of clinical depression are strongly correlated with vascular disease risk, creating a comorbid condition with poor outcomes but demonstrating a sexual disparity whereby female subjects are at lower risk than male subjects for subsequent cardiovascular events. To determine the potential mechanisms responsible for this protection against stress/depression-induced vasculopathy in female subjects, we exposed male, intact female, and ovariectomized (OVX) female lean Zucker rats to the unpredictable chronic mild stress (UCMS) model for 8 wk and determined depressive symptom severity, vascular reactivity in ex vivo aortic rings and middle cerebral arteries (MCA), and the profile of major metabolites regulating vascular tone. While all groups exhibited severe depressive behaviors from UCMS, severity was significantly greater in female rats than male or OVX female rats. In all groups, endothelium-dependent dilation was depressed in aortic rings and MCAs, although myogenic activation and vascular (MCA) stiffness were not impacted. Higher-resolution results from pharmacological and biochemical assays suggested that vasoactive metabolite profiles were better maintained in female rats with normal gonadal sex steroids than male or OVX female rats, despite increased depressive symptom severity (i.e., higher nitric oxide and prostacyclin and lower H2O2 and thromboxane A2 levels). These results suggest that female rats exhibit more severe depressive behaviors with UCMS but are partially protected from the vasculopathy that afflicts male rats and female rats lacking normal sex hormone profiles. Determining how female sex hormones afford partial vascular protection from chronic stress and depression is a necessary step for addressing the burden of these conditions on cardiovascular health.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY This study used a translationally relevant model for chronic stress and elevated depressive symptoms to determine how these factors impact conduit and resistance arteriolar function in otherwise healthy rats. While chronic stress leads to an impaired vascular reactivity associated with elevated oxidant stress, inflammation, and reduced metabolite levels, we demonstrated partial protection from vascular dysfunction in female rats with normal sex hormone profiles compared with male or ovariectomized female rats.

Keywords: cardiovascular risk factors, chronic stress, clinical depression, endothelial dysfunction, sex disparities, vasodilation

INTRODUCTION

Irresolvable psychological stress is increasingly recognized as a key risk factor for poor health outcomes (6, 8, 22). While some individuals can adapt to minimize the burden of chronic stress on health, many are unable to incorporate ameliorative measures or manifest a greater susceptibility to stress, such that clinical depression or depressed states evolve. Furthermore, the presence of chronic stress and elevated depressive symptoms represents a significant factor for elevated cardiovascular disease risk, vascular dysfunction, and pathological vasculopathies in human cohorts (8, 15, 24, 46) and rodent models (1, 8, 40, 49). Of particular relevance to the present study, a sex-based disparity in depressive symptom severity and the subsequent health outcomes is becoming increasingly apparent (21, 32, 41). However, major cardiovascular events occur at a lower rate in premenopausal women than in men, despite the presence of comparable cardiovascular disease risk factors, including depression (46).

The unpredictable chronic mild stress (UCMS) model is an established, translationally relevant model based on its ability to reproduce behavioral and endocrine characteristics (23, 27, 54, 55). In previous research, the UCMS model has been used to demonstrate an association of the presence of chronic stress and the induction of depressive symptoms in mouse (11) and rat (27, 55) models with impaired conduit artery endothelial function, with the mechanistic bases of this dysfunction being associated with chronic vascular inflammation and oxidant stress. In addition, in previous studies, the UCMS protocol showed a greater susceptibility to depressive symptoms (17, 48) but better-maintained endothelial function in female than male rodents (49). These protective effects on vascular function in female subjects with chronic stress were correlated to estrogen levels, potentially promoting antioxidant defense and maintaining endothelial function (7, 9, 23, 31). However, a more detailed analysis of the mechanistic contributors to this protection in female subjects is lacking, as is extension of these observations to resistance vasculature.

A study of this challenge to human health requires a more detailed understanding of not only the nature of vasculopathy in conduit arteries and resistance arterioles with the development of chronic stress and depression but also how a vascular protection that may be associated with the female sex manifests itself in terms of the mechanistic nature of dilator and constrictor responses. The present study determined the impact of chronic stress and elevated depressive symptoms on fundamental indexes of reactivity of conduit artery rings and pressurized middle cerebral arteries (MCA) from male, female, and ovariectomized (OVX) female rats subjected to the UCMS protocol. In addition, the present study was designed to determine mechanistic contributors to differences in vascular outcomes between sexes to gain insights into the protective effect on vascular function that has been demonstrated in female subjects. The general hypothesis tested by this study is that UCMS-induced proinflammatory/prooxidant states within the vasculature are better tolerated in female rats than in male rats, resulting in better-maintained vascular reactivity. It is further hypothesized that this improved vascular outcome reflects the presence of female sex hormones, inasmuch as OVX surgery before imposition of UCMS in female rats will result in outcomes comparable with those in male rats. A deeper understanding of vascular and, particularly, cerebrovascular impairments associated with chronic stress and depressive symptoms and their mechanistic underpinnings will be critical in terms of our understanding of how to combat this emerging challenge to human health and may provide deeper insights into the links between vascular and behavioral/cognitive health.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Male (n = 12) and female (n = 12) lean Zucker rats (Harlan/Envigo) were purchased at ~8 wk of age and maintained on standard chow and drinking water ad libitum for the duration of the study. All animals were housed in an accredited animal care facility at the University of Western Ontario or the West Virginia University Health Sciences Center, and all procedures had received prior Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approval. A separate cohort of female lean Zucker rats (n = 12, Harlan/Envigo) was acquired at the same age after OVX surgery, which was performed between 5 and 6 wk of age by the supplier, and were similarly housed. At 9 wk of age, rats from each sex/condition were divided into the following two groups: control (n = 6 for each, all with normal handling, with the exception of the UCMS protocol) and UCMS (n = 6 for each, see below). After 8 wk under control or UCMS conditions, rats were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg ip), and a carotid artery was cannulated for the determination of mean arterial pressure. From each animal, a venous blood sample was also acquired (venipuncture) for the determination of circulating endocrine, oxidant, and inflammatory biomarkers. Thereafter, rats received a low dose of heparin (100 IU/kg iv) to prevent the formation of blood clots during tissue harvest.

UCMS Protocol

All rats were singly housed. The control group was housed in a separate quiet room adjacent to the room used for UCMS treatments. The UCMS group was randomly exposed to the following environmental stressors daily throughout each 24-h period: 1) damp bedding (addition of 10 oz of water to each standard cage for the next 3 h); 2) water [removal of all bedding and addition of ~0.5 in. of ~30°C water to the empty cage for the next 3 h (room temperature was ~24°C)]; 3) cage tilted to 45° with or without bedding for 3 h; 4) social stress (rat was switched into the cage of a neighboring rat for 3 h); 5) no bedding for 3 h or, on 2 occasions/wk, overnight; 6) succession of 30-min light-dark cycles throughout a 24-h period; and 7) exposure to predator smells (e.g., cat fur) and/or sounds (e.g., cat growling) for 8 h. After 8 wk, all rats were subjected to a series of behavioral tests to evaluate the outcomes of the UCMS procedures [for a full description of the UCMS protocol, see Frisbee et al. (19)].

Coat Status

Coat status was evaluated throughout the duration of the UCMS protocol, as previously described elsewhere (54). The total cumulative score was computed from an individual score of 0 (clean) or 1 (dirty) assigned to eight body parts (head, neck, dorsal coat, ventral coat, tail, forelimb, hindlimb, and genital region).

Sucrose Spray Test

The sucrose spray test was used to evaluate acute grooming behavior, defined as cleaning of the fur by licking or scratching (54). A 10% sucrose solution was sprayed on the dorsal coat of each rat, and grooming activity was recorded for 5 min. The viscosity of the sucrose solution will dirty the coat and induce grooming behavior, with depressive symptoms characterized by an increased latency (idle time between spray and initiation of grooming) and decreased frequency (number of times a particular body part is groomed).

Novelty Suppressed Feeding Test

The novelty suppressed feeding test was performed as previously described (50). At the conclusion of the UCMS period, all access to food was removed from the rats for 24 h (ad libitum access to water was continued). Subsequently, individual rats were placed in one corner of an empty cage (18 × 24 in.) with fresh bedding. One pellet of the normal chow was placed in the center of the cage. The time from placement of the food pellet to the moment when the rat actually began consuming (i.e., not just sniffing and handling) the food pellet was noted. At this time, the animal was removed from the cage and returned to its home cage, and normal access to food was restored.

Measurements of Vascular Reactivity

Conduit arteries.

After the initial surgery, the thoracic aorta was removed, rinsed in physiological salt solution (PSS), cleared of surrounding tissue, and cut into 2- to 3-mm rings. Each ring was mounted in a myobath chamber between a fixed point and a force transducer (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) and set to 0.5 g of tension for 45 min to equilibrate. Organ baths contained PSS at 37°C and were aerated with 95% O2-5% CO2. Rings were preconditioned by treatment with 10−7 M phenylephrine for 5 min, at which time 10−5 M methacholine was added to the bath to assess endothelial integrity. Any ring that failed to demonstrate both a brisk constrictor response to phenylephrine and viable endothelial function was discarded. Subsequently, rings were treated with increasing concentrations of phenylephrine (10−10–10−4 M) to assess constrictor reactivity. For assessment of relaxation, rings were pretreated with 10−6 M phenylephrine and exposed to increasing concentrations of methacholine (10−10–10−4 M) and sodium nitroprusside (10−10–10−4 M). To assess the roles of nitric oxide (NO), cyclooxygenase, and reactive oxidant stress in modulating vascular responses to the agonist treatments, concentration-response curves were also conducted after pretreatment of the rings for 45–60 min with N-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME; 10−4 M), indomethacin (10−5 M), and tempol (10−4 M), respectively.

Immediately after removal of the aorta, each rat was decapitated, and the brain was removed from the skull case and placed in cold (4°C) PSS. Subsequently, a MCA was dissected from its origin at the circle of Willis. Each MCA was doubly cannulated in a heated (37°C) chamber that allowed perfusion and superfusion of the lumen and exterior of the vessel, respectively, with PSS from separate reservoirs. The PSS, which was equilibrated with 21% O2-5% CO2-74% N2, had the following composition (in mM): 119 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 1.17 MgSO4, 1.6 CaCl2, 1.18 NaH2PO4, 24 NaHCO3, 0.026 EDTA, and 5.5 glucose. Any side branches were ligated using a single strand teased from 6-0 suture. Vessel diameter was measured using television microscopy and an on-screen video micrometer.

Isolated MCAs.

After cannulation, MCAs were extended to their in situ length and equilibrated at 80% of the animal's mean arterial pressure to approximate in vivo perfusion pressure (18). Any vessel that did not demonstrate significant active tone at the equilibration pressure was discarded. Active tone at the equilibration pressure was calculated as (ΔD/Dmax) × 100, where ΔD is the diameter increase from rest in response to Ca2+-free PSS and Dmax is the maximum diameter measured at the equilibration pressure in Ca2+-free PSS.

After equilibration, MCA dilation was assessed in response to increasing concentrations (10−10 M–10−6 M) of acetylcholine (ACh). Vascular responses to ACh were also measured after acute (45–60 min) incubation with l-NAME (10−4 M), indomethacin (10−5 M), and/or tempol (10−4 M).

To determine myogenic activation, the vessel perfusate outflow line was clamped, stopping perfusate flow through the vessel, and the height of the perfusion reservoir was changed to vary intraluminal pressure in 20-mmHg increments between 40 and 160 mmHg. Vessel diameter was determined after 10–15 min at each pressure, and pressure levels were randomized for each myogenic activation curve. After completion of all procedures, the perfusate and superfusate were replaced with Ca2+-free PSS, and the passive diameter of the fully relaxed vessel was determined over the identical intraluminal pressure range.

Measurement of Vascular NO and H2O2 Levels

From each rat, pooled conduit arteries (e.g., carotid, femoral, iliac, distal aorta, and saphenous) were harvested for the determination of vasoactive metabolite levels. Vascular NO and H2O2 production were assessed using amperometric sensors (World Precision Instruments). Briefly, arteries were isolated, placed in a sealed reaction chamber, and incubated with warmed (37°C) PSS equilibrated with 95% O2-5% CO2. A NO sensor (model ISO-NOPF100, World Precision Instruments) and a H2O2 sensor (model ISO-HPO100, World Precision Instruments) were inserted into the chamber, and baseline levels of current were obtained. Subsequently, increasing concentrations (10−10–10−6 M) of methacholine were added to the bath, and changes in “NO” and “H2O2” currents were determined.

Determination of Vascular Metabolites of Arachidonic Acid

Vascular production of 6-keto-PGF1α (the stable breakdown product of PGI2 (38)] and 11-dehydro-thromboxane (Tx)B2 [the stable plasma breakdown product of TxA2 (43)] in response to challenge with reduced Po2 was assessed using the pooled conduit arteries. Pooled arteries from each animal were incubated in microcentrifuge tubes in 1 ml PSS for 30 min under control conditions (21% O2). The superfusate was removed, stored in a new microcentrifuge tube, and frozen in liquid N2; a new aliquot of PSS was added to the vessels, and the equilibration gas was switched to 0% O2 for 30 min. After the second 30-min period, this new PSS was transferred to a fresh tube, frozen in liquid N2, and stored at −80°C. Metabolite release by the vessels was determined using commercially available enzyme immunoassay kits for 6-keto-PGF1α and 11-dehydro-TxB2 (Cayman Chemical).

Biochemical Analyses

Plasma corticosterone and nitrotyrosine levels were determined using commercially available ELISA kits (Cayman Chemical). Sex hormone profiles were determined on a fee-for-service basis by a professional clinical laboratory using commercially available ELISA kits (MyBioSource, Cayman Chemical). All other plasma biomarkers (e.g., insulin and biomarkers of inflammation) were measured using commercially available kits and multiplexed bioassay systems (Meso Scale Diagnostics or Luminex/ThermoFisher).

Data and Statistical Analyses

Mechanical responses after challenge with logarithmically increasing doses of methacholine/ACh were fit with the following three-parameter logistic equation:

where y is the vessel diameter, min and max are the lower (minimum) and upper (maximum) bounds, respectively, of the change in diameter or tension development with agonist concentration, x is the logarithm of the agonist concentration, and logED50 is the logarithm of the agonist concentration (x) where the response (y) is halfway between the bounds. For the presentation of results, we focused on changes in the bounds as a representation of vessel reactivity, as one bound will remain consistent between all groups (defined as the prechallenge diameter), and we did not determine a consistent or significant change in logED50 values between treatment groups. As a result of this approach, the other bound represents that statistically determined asymptote for the concentration-response relationship and does not assume that the vascular response at the highest utilized concentration of the agonist represents the maximum possible response. Rather, the sigmodal relationship of best fit to the data will predict the statistical bound of the response given the data points entered into the model. As such, the bound is frequently slightly larger than the dilation of the vessel at the highest concentration of the agonist.

The myogenic properties of MCAs from each experimental group were plotted as mean diameter at each intraluminal pressure and fitted with a linear regression: [y = α0 + βx, where the slope coefficient β is the degree of myogenic activation (δdiameter/δpressure)]. Increasingly negative values of β, therefore, represent a greater degree of myogenic activation in response to changes in intravascular pressure. A similar analysis was used to determine NO and H2O2 levels in response to increasing concentrations of methacholine, where β is the rate of change of NO or H2O2 released by the vessels in response to agonist challenge.

All calculations of passive arteriolar wall mechanics (used as indicators of structural alterations to the individual microvessel) are based on those previously used (2) with minor modification. Vessel wall thickness (WT; in μm) was calculated as follows:

where OD and ID are arteriolar outer and inner diameters (in μm), respectively.

Incremental arteriolar distensibility (Distinc; in %change in arteriolar diameter/mmHg) was calculated as follows:

where ΔID is the change in internal arteriolar diameter for each incremental change in intraluminal pressure (ΔPIL).

For the calculation of circumferential stress, intraluminal pressure was converted from mmHg to N/m2, where 1 mmHg = 1.334 × 102 N/m2. Circumferential stress (σ) was then calculated as follows:

Circumferential strain (ε) was calculated as follows:

where ID5 is the internal arteriolar diameter at the lowest intravascular pressure (i.e., 5 mmHg). The stress-strain relationship from each vessel was fit (ordinary least squares analysis, r2 > 0.85) with the following exponential equation:

where σ5 is circumferential stress at ID5 and β is the slope coefficient describing arterial stiffness. Higher levels of β are indicative of increasing arterial stiffness (i.e., requiring a greater degree of distending pressure to achieve a given level of wall deformation).

Values are means ± SE. Differences in all calculated parameters or descriptive characteristics between the different experimental groups in the present study were assessed using ANOVA with a Student-Newman-Keuls test post hoc, as appropriate. In all cases, P < 0.05 was taken to reflect statistical significance.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows baseline data from all groups of animals. Among the control animals, age-matched male rats were larger than female or OVX female rats; there were no other consistent or significant differences between groups. Plasma corticosterone levels were higher in female and OVX female rats than male rats, but this was the only significant difference in plasma biomarker profiles. In UCMS animals, these relationships were generally maintained, although glycemic control was impaired in all groups as a result of UCMS and levels of nitrotyrosine and specific biomarkers of inflammation (e.g., TNF-α) were increased and differences in corticosterone were further amplified.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Control |

Unpredictable Chronic Mild Stress |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | OVX | Male | Female | OVX | |

| Mass, g | 391 ± 7 | 354 ± 5* | 342 ± 8* | 422 ± 12 | 344 ± 10* | 385 ± 10* |

| Mean arterial pressure, mmHg | 105 ± 4 | 102 ± 3 | 106 ± 4 | 111 ± 4 | 114 ± 6 | 117 ± 5 |

| Glucose, mg/dl | 123 ± 6 | 114 ± 5 | 190 ± 8*† | 154 ± 11‡ | 136 ± 6§ | 205 ± 12*† |

| Insulin, ng/ml | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 3.8 ± 0.3‡ | 2.5 ± 0.3*§ | 3.1 ± 0.3 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dl | 77 ± 8 | 60 ± 10 | 62 ± 7 | 72 ± 8 | 78 ± 6 | 62 ± 9 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dl | 104 ± 10 | 96 ± 11 | 127 ± 9*† | 98 ± 9 | 88 ± 11 | 130 ± 10*† |

| Nitrotyrosine, pg/ml | 14 ± 3 | 12 ± 4 | 17 ± 4 | 28 ± 5‡ | 21 ± 4 | 30 ± 5 |

| Corticosterone, ng/ml | 87 ± 7 | 161 ± 10* | 149 ± 10* | 129 ± 14‡ | 250 ± 20*§ | 170 ± 11*† |

| TNF-α, pg/ml | 2.9 ± 0.3 | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 7.0 ± 0.4*† | 5.3 ± 0.5‡ | 6.4 ± 0.6§ | 7.1 ± 0.5 |

| IL-6, pg/ml | 26 ± 4 | 21 ± 5 | 51 ± 6*† | 38 ± 5 | 30 ± 4 | 56 ± 7*† |

| IL-1β, pg/ml | 6.3 ± 0.4 | 6.2 ± 0.5 | 12.0 ± 0.5*† | 10.6 ± 0.5‡ | 13.3 ± 0.8§ | 15.3 ± 1.3* |

| Interferon-γ, pg/ml | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 1.9 ± 0.2* | 1.0 ± 0.3*† | 0.8 ± 0.2‡ | 0.7 ± 0.2§ | 1.4 ± 0.4 |

| IL-10, pg/ml | 6.0 ± 0.5 | 4.5 ± 0.4 | 5.1 ± 0.5 | 4.4 ± 0.6‡ | 4.4 ± 0.4 | 8.9 ± 1.1*† |

Values are means ± SE. OVX, ovariectomy.

P < 0.05 vs. male animals in that condition;

P < 0.05 vs. female animals in that condition;

P < 0.05 vs. male control animals;

P < 0.05 vs. female control animals.

Table 2 shows the data describing the sex hormone profiles for male, female, and OVX female rats under control conditions and after the UCMS protocol. Plasma testosterone, although normal in male rats, was significantly reduced after the imposition of UCMS. Estradiol and progesterone levels in female rats were largely unaffected by UCMS but were dramatically reduced after OVX surgery. Luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone levels were relatively low in male and female rats but were increased with OVX surgery.

Table 2.

Sex hormone profiles

| Control |

Unpredictable Chronic Mild Stress |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | OVX | Male | Female | OVX | |

| Testosterone, ng/ml | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.3* | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 |

| Estradiol, pg/ml | 20.2 ± 4.1 | 70.8 ± 5.7 | 16.0 ± 3.9† | 17.7 ± 4.6 | 61.8 ± 5.6 | 12.2 ± 4.1† |

| Progesterone, ng/ml | 5.9 ± 1.9 | 31.3 ± 5.0 | 7.2 ± 1.8† | 3.9 ± 1.1 | 28.4 ± 5.6 | 5.3 ± 2.2† |

| Follicle-stimulating hormone, ng/ml | 6.8 ± 1.6 | 8.9 ± 2.9 | 26.4 ± 5.2† | 4.2 ± 1.1 | 10.9 ± 2.7 | 34.4 ± 5.6† |

| Luteinizing hormone, ng/ml | 5.2 ± 0.9 | 7.2 ± 2.0 | 32.4 ± 5.7† | 2.9 ± 0.8 | 8.4 ± 1.7 | 29.1 ± 4.9† |

Values are means ± SE. OVX, ovariectomy.

P < 0.05 vs. control responses;

P < 0.05 vs. female animals.

Behavioral Responses

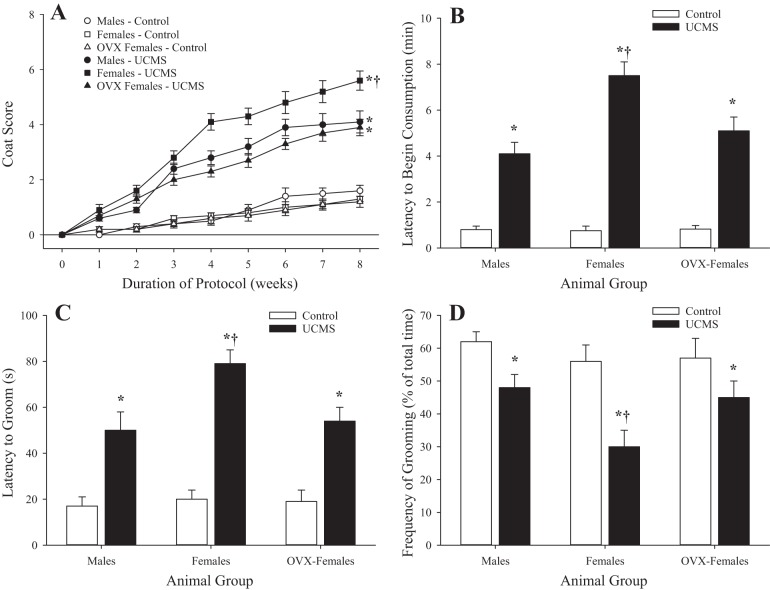

Figure 1 shows the behavioral data and severity of the depressive symptoms after UCMS. While there were no differences in coat score between male, female, and OVX female rats under control conditions, coat status was significantly worse in all groups of UCMS rats compared with control rats; this difference was particularly striking in female rats (Fig. 1A). In terms of the novelty suppressed feeding response, all three groups demonstrated a similar latency to the initiation of feeding under control conditions, which was delayed by the imposition of UCMS; female rats demonstrated the greatest latency (Fig. 1B). In response to application of the sucrose spray, the latency of grooming after spray (Fig. 1C) was increased with UCMS in all groups compared with the control group, whereas the percentage of time spent grooming after spray (Fig. 1D) was reduced. For both latency to groom and percentage of time spent grooming after spray, these responses were exacerbated in female rats compared with male or OVX female rats.

Fig. 1.

Behavioral responses of male, female, and ovariectomized (OVX) female rats under control conditions and after 8 wk of unpredictable chronic mild stress (UCMS). Coat score (A), novelty suppressed feeding response (B), and latency to start grooming (C) and frequency of subsequent grooming (D) after sucrose spray are shown. Values are means ± SE; n = 6 for each group. *P < 0.05 vs. control in that group; †P < 0.05 vs. UCMS male rats.

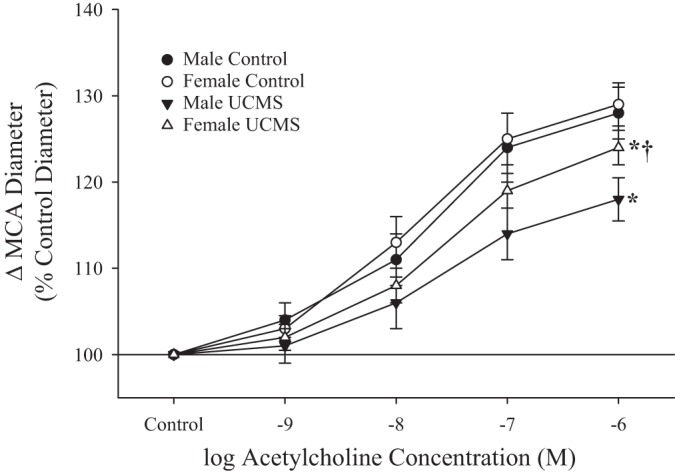

Relaxation of Aortic Rings

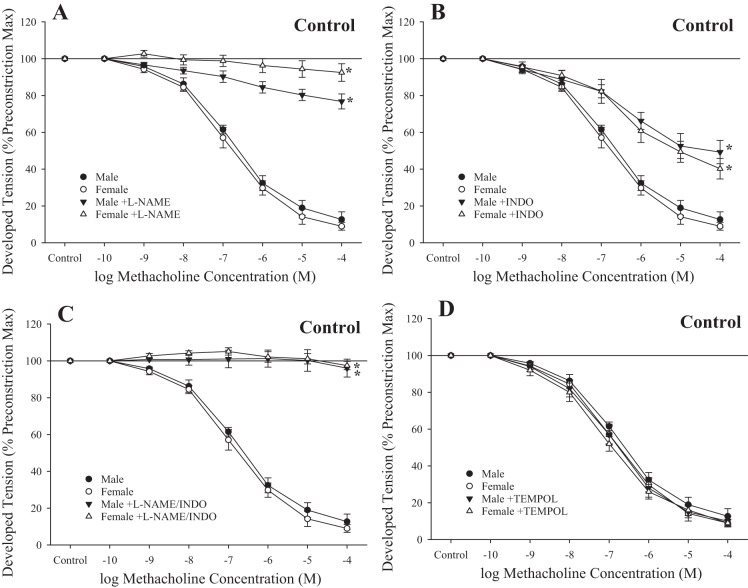

Data describing the reactivity of ex vivo aortic rings from male and female rats under control conditions and after UCMS in response to increasing concentrations of methacholine are shown in Fig. 2. In control male and female rats, an increase in agonist concentration resulted in a robust relaxation that was attenuated in both sexes after UCMS. Impairment of the relaxation was greater in vessels from male rats than female rats.

Fig. 2.

Relaxation of ex vivo aortic rings in response to increasing concentrations of methacholine from male and female rats under control conditions and after 8 wk of unpredictable chronic mild stress (UCMS). Values are means ± SE; n = 6 for each group. *P < 0.05, lower bound vs. control in that group; †P < 0.05, lower bound vs. UCMS male rats.

Figure 3 shows the impact of pharmacological inhibitors of the fundamental pathways comprising methacholine-induced responses in rings from control male and female rats. In response to treatment with l-NAME, rings from male and female rats demonstrated a severely impaired response to increasing concentrations of methacholine (Fig. 3A). Treatment with indomethacin resulted in a modest, but significant, impaired relaxation to methacholine (Fig. 3B), whereas responses to l-NAME + indomethacin largely abolished relaxation to the agonist (Fig. 3C). Treatment with the antioxidant tempol had no significant impact on methacholine-induced relaxation in rings from either sex (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

Relaxation of ex vivo aortic rings in response to increasing concentrations of methacholine from male and female rats under control conditions. Data are shown for ex vivo aortic rings under control (untreated) conditions and after acute inhibition of nitric oxide synthase with N-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME; A), after acute inhibition of cyclooxygenase with indomethacin (INDO; B) and l-NAME + INDO (C), and after pretreatment with the antioxidant tempol (D). Values are means ± SE; n = 6 for each group. *P < 0.05, lower bound vs. control in that group.

The effect of pharmacological inhibition of methacholine-induced responses in ex vivo aortic rings from male and female rats after UCMS is shown in Fig. 4. While l-NAME had minimal impact on the lower bound of relaxation in rings from male rats after UCMS, inhibition of NO synthase significantly reduced this response in rings from female rats after UCMS (Fig. 4A). In contrast, treatment with indomethacin resulted in a blunted response to methacholine in both sexes after UCMS (Fig. 4B), whereas l-NAME + indomethacin abolished reactivity of rings to the agonist in both groups (Fig. 4C). Tempol improved methacholine-induced relaxation of aortic rings in male and female rats after UCMS (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4.

Relaxation of ex vivo aortic rings in response to increasing concentrations of methacholine from male and female rats after 8 wk of unpredictable chronic mild stress (UCMS). Data are presented for ex vivo aortic rings under control (untreated) conditions and after acute inhibition of nitric oxide synthase with N-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME; A), after acute inhibition of cyclooxygenase with indomethacin (INDO; B) and l-NAME + INDO (C), and after pretreatment with the antioxidant tempol (D). Values are means ± SE; n = 6 for each group. *P < 0.05, lower bound vs. control in that group; †P < 0.05, lower bound vs. UCMS male rats.

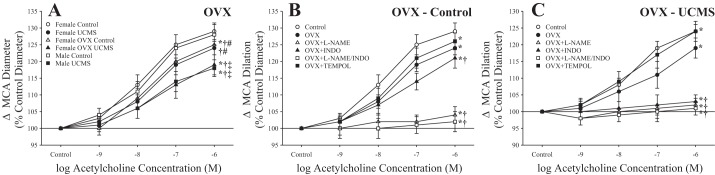

Effects of OVX Surgery on Aortic Relaxation

Figure 5 shows the effects of OVX surgery in female rats before UCMS on relaxation of aortic rings. Placed on the same axes as male and female rats (with or without UMCS), the results for OVX female rats were modestly inhibited compared with those for intact animals under control conditions but were extremely comparable to the responses for male rats after UCMS (Fig. 5A). Figure 5B shows the basic mechanistic contributors to the methacholine-induced responses of rings from OVX female rats under control conditions, demonstrating a strong contribution of NO levels (based on responses after l-NAME treatment) and a modest contribution from arachidonic acid metabolites (based on responses after indomethacin treatment). Pretreatment of aortic rings with tempol resulted in an increased relaxation after challenge with methacholine. The mechanistic contributors to the dilation to methacholine after UCMS are shown in Fig. 5C. Whereas l-NAME (alone or in combination with indomethacin) almost completely abolished relaxation to methacholine in rings from OVX female rats after UCMS, treatment with indomethacin alone or tempol resulted in an improved reactivity.

Fig. 5.

Relaxation of ex vivo aortic rings from ovariectomized (OVX) female rats in response to increasing concentrations of methacholine under control conditions and after 8 wk of unpredictable chronic mild stress (UCMS). A: responses superimposed on comparable responses from male and female rats under control conditions and after UCMS. B and C: methacholine-induced responses of ex vivo aortic rings from control and UCMS OVX female rats, respectively, under untreated conditions and in response to pretreatment with N-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME), indomethacin (INDO), l-NAME + INDO, or tempol. Values are means ± SE; n = 6 for each group. In A, *P < 0.05, lower bound vs. control male rats; †P < 0.05, lower bound vs. control female rats; #P < 0.05, lower bound vs. UCMS male rats; ‡P < 0.05, lower bound vs. UCMS female rats. In B and C, *P < 0.05, lower bound vs. control female rats; †P < 0.05, lower bound vs. OVX female rats.

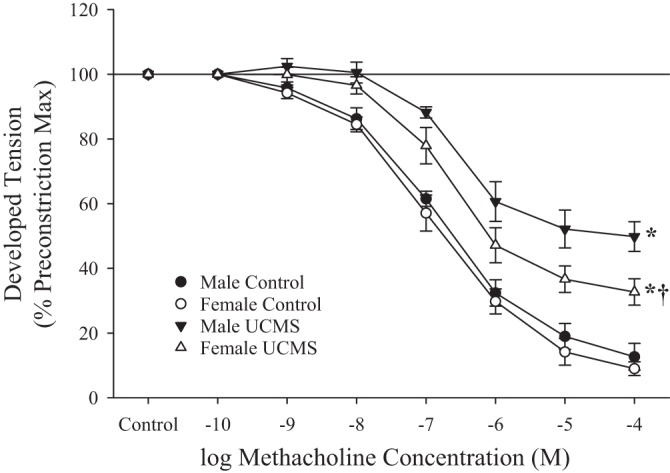

Dilation of MCAs

The characteristics of isolated MCAs across the groups in the present study are shown in Table 3. While there were some general drifts in the data regarding the effects of sex or UCMS in terms of diameters at the equilibration pressures and the level of active tone, results across groups were not significantly different.

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics of isolated middle cerebral arteries at equilibration pressures

| Control |

Unpredictable Chronic Mild Stress |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | OVX | Male | Female | OVX | |

| Equilibration pressure, mmHg | 84 ± 4 | 81 ± 3 | 82 ± 4 | 89 ± 5 | 83 ± 3 | 90 ± 5 |

| Active inner diameter, μm | 118 ± 4 | 114 ± 5 | 115 ± 4 | 108 ± 5 | 114 ± 5 | 110 ± 4 |

| Passive inner diameter, μm | 190 ± 4 | 188 ± 4 | 186 ± 5 | 182 ± 5 | 186 ± 6 | 178 ± 5 |

| Active tone, % | 37 ± 3 | 39 ± 4 | 38 ± 4 | 40 ± 3 | 38 ± 4 | 38 ± 3 |

There were no statistically significant differences between groups. OVX, ovariectomy.

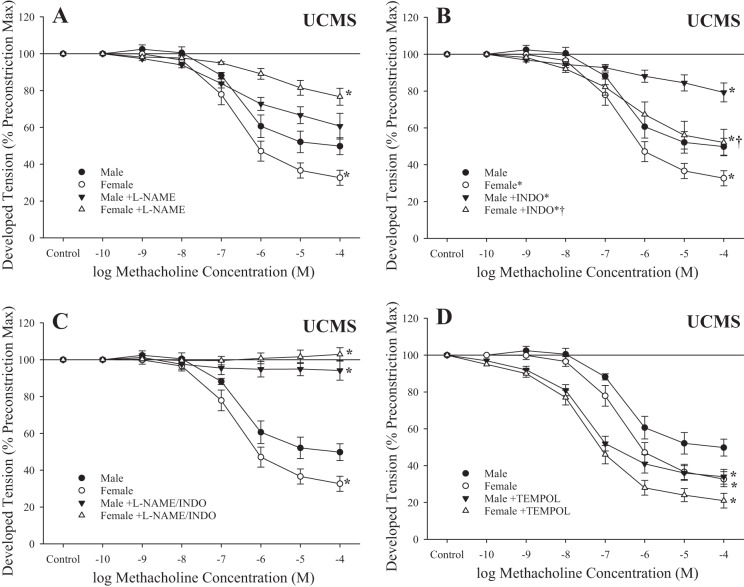

Figure 6 shows responses of isolated MCAs to increasing concentrations of ACh in male and female rats under control conditions and after UCMS. In both sexes, UCMS blunted dilator responses, although this effect was less pronounced in female rats.

Fig. 6.

Dilation of isolated middle cerebral arteries (MCAs) in response to increasing concentrations of acetylcholine in male and female rats under control conditions and after 8 wk of unpredictable chronic mild stress (UCMS). Values are means ± SE; n = 6 for each group. *P < 0.05, upper bound vs. control in that group; †P < 0.05, upper bound vs. UCMS male MCAs.

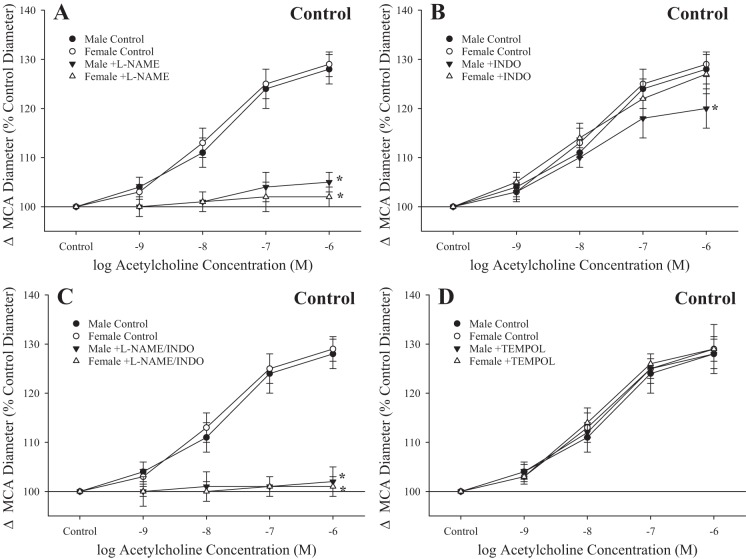

The basic mechanistic contributors to ACh-induced dilation in MCA from male and female rats under control conditions are shown in Fig. 7. In both sexes, ACh-induced dilation was largely dependent on NO production, as pretreatment of vessels with l-NAME (alone or in combination with indomethacin) abolished reactivity (Fig. 7, A and C) and was not significantly dependent on arachidonic acid metabolites, as pretreatment of vessels with indomethacin was largely without effect (except at the highest dose of agonist, in male rats only; Fig. 7B). Treatment with the antioxidant tempol had no effect on responses in MCAs from either sex (Fig. 7D).

Fig. 7.

Dilation of isolated middle cerebral arteries (MCAs) in response to increasing concentrations of acetylcholine in male and female rats under control conditions. Data are presented for MCAs under control (untreated) conditions and after acute inhibition of nitric oxide synthase with N-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME; A), after acute inhibition of cyclooxygenase with indomethacin (INDO) (B) and l-NAME + INDO (C), and after pretreatment with the antioxidant tempol (D). Values are means ± SE; n = 6 for each group. *P < 0.05, upper bound vs. control in that group.

After UCMS, l-NAME had an impact very similar to that under control conditions, nearly abolishing reactivity to ACh in MCAs from either sex (Fig. 8, A and C), whereas indomethacin alone did not result in a significant change in dilation to increasing concentration of the agonist (Fig. 8B). Pretreatment of MCAs with tempol resulted in an improved dilation in vessels from male rats after UCMS, but this effect was not statistically significant in MCAs from female rats (Fig. 8D).

Fig. 8.

Dilation of isolated middle cerebral arteries (MCAs) in response to increasing concentrations of acetylcholine in male and female rats after 8 wk of unpredictable chronic mild stress (UCMS). Data are presented for MCAs under control (untreated) conditions and after acute inhibition of nitric oxide synthase with N-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME; A), after acute inhibition of cyclooxygenase with indomethacin (INDO; B) and l-NAME + INDO (C), and after pretreatment with the antioxidant tempol (D). Values are means ± SE; n = 6 for each group. *P < 0.05, upper bound vs. control in that group.

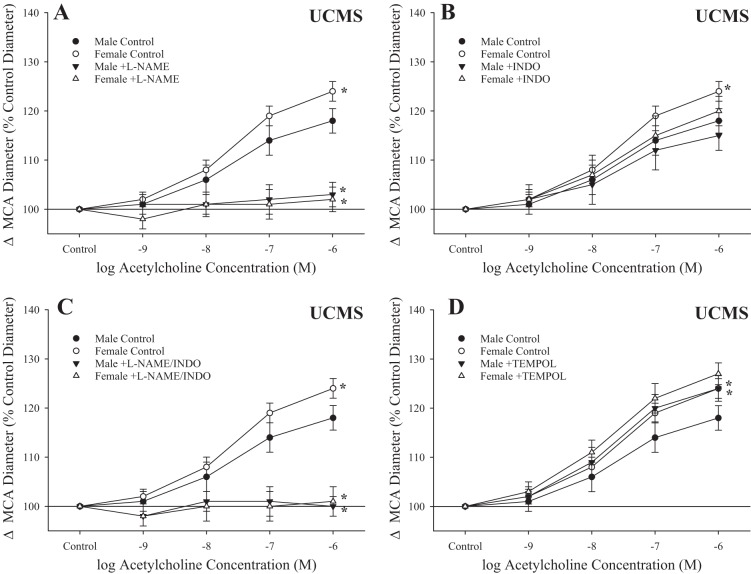

Effects of OVX on MCA Dilation

After OVX surgery, dilation of MCAs under control conditions exhibited a level of reactivity very similar to that in intact female rats after UCMS (Fig. 9A), while the response to UCMS was identical to that for male rats subjected to the UCMS protocol. Whereas indomethacin or tempol had minimal impact on responses of MCA from OVX females to ACh under control conditions, l-NAME largely abolished responses to increasing concentrations of the agonist (Fig. 9B). In contrast, whereas pretreatment with tempol improved ACh-induced dilation of MCAs from OVX female rats after UCMS (Fig. 9C), l-NAME and indomethacin (alone or in combination) almost completely abolished all dilator reactivity to the agonist.

Fig. 9.

Dilation of isolated middle cerebral arteries (MCAs) from ovariectomized (OVX) female rats in response to increasing concentrations of acetylcholine under control conditions and after 8 wk of unpredictable chronic mild stress (UCMS). A: responses superimposed on the comparable responses from male and female rats under control conditions and after UCMS. B and C: acetylcholine-induced responses of MCAs from control and UCMS OVX female rats, respectively, under untreated conditions and in response to pretreatment with N-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME), indomethacin (INDO), l-NAME + INDO, or tempol. Values are means ± SE; n = 6 for each group. In A, *P < 0.05, upper bound vs. control male rats; †P < 0.05, upper bound vs. control female rats; #P < 0.05, upper bound vs. UCMS male rats; ‡P < 0.05, upper bound vs. UCMS female rats. In B and C, *P < 0.05, upper bound vs. control female rats; †P < 0.05, upper bound vs. OVX female rats.

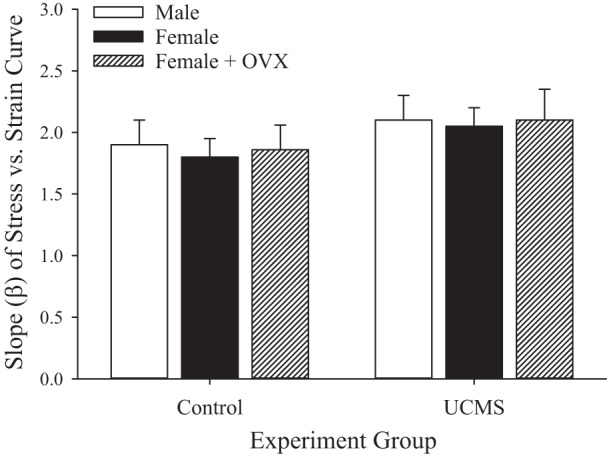

Figure 10 shows the myogenic activation of MCAs in response to increasing intravascular pressure from the groups of animals in the present study. In response to elevated pressure, myogenic activation from all groups was similar in terms of the slope coefficient (β) describing the response; no significant differences were evident.

Fig. 10.

Myogenic activation of isolated middle cerebral arteries (MCAs) in response to increasing intravascular pressure in male, female, and ovariectomized (OVX) female rats under control conditions and after 8 wk of unpredictable chronic mild stress (UCMS). Values are means ± SE; n = 6 for each group. There were no statistically significant differences in myogenic activation between groups.

The impact of sex or UCMS on the mechanics of the vessel wall in the MCA is shown in Fig. 11 as β from the stress-strain relationship under conditions of zero active tone. While there was some general noise in the data, the differences in β describing these relationships were not significantly different between groups.

Fig. 11.

Slope coefficient (β) from stress-strain relationship for isolated middle cerebral arteries in response to increasing intravascular pressure (under Ca2+-free conditions) in male, female, and ovariectomized (OVX) female rats under control conditions and after 8 wk of unpredictable chronic mild stress (UCMS). Values are means ± SE; n = 6 for each group. There were no statistically significant differences between groups.

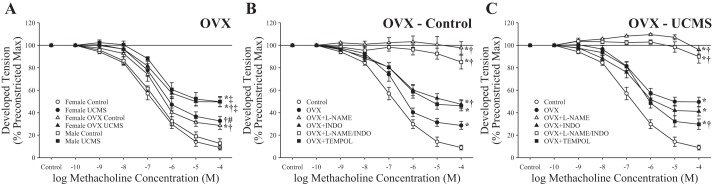

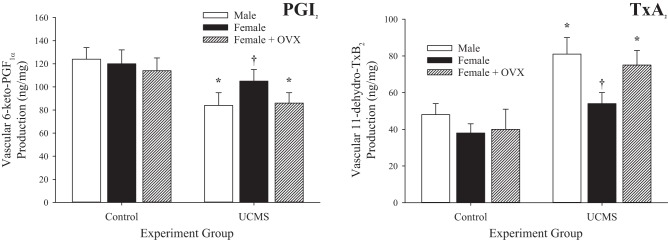

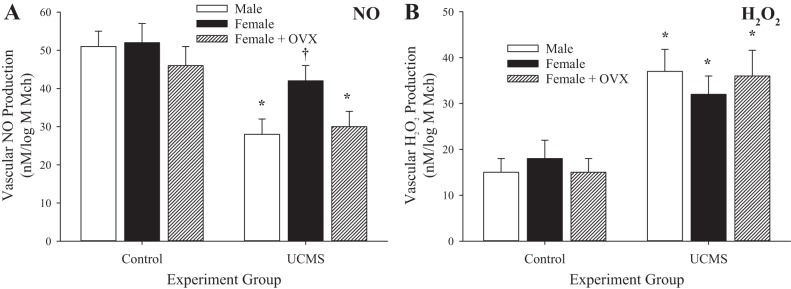

Effects of UCMS and OVX on Dilator Metabolites

Data describing the arterial production of PGI2 (from its breakdown metabolite 6-keto-PGF1α) and TxA2 (from its breakdown metabolite 11-dehydro-TxB2) under the conditions of the present study are shown in Fig. 12. In all groups (male, female, and OVX female rats), PGI2 production was reduced in response to 8 wk of UCMS (Fig. 12A), whereas arterial production of TxA2 was increased (Fig. 12B). However, these changes in arachidonic acid metabolism were attenuated in arteries of intact female rats compared with male or OVX female rats.

Fig. 12.

Vascular production of PGI2 (A) and thromboxane (Tx)A2 (B) in male, female, and ovariectomized (OVX) female rats under control conditions and after 8 wk of unpredictable chronic mild stress (UCMS). Data are presented as the production of 6-keto-PGF1α and 11-dehydro-TxB2, the stable breakdown products of PGI2 and TxA2, respectively. Values are means ± SE; n = 6 for each group. *P < 0.05 vs. control conditions; †P < 0.05 vs. UCMS male rats.

Figure 13 shows vascular NO and H2O2 levels under control conditions and after UCMS. Similar to the levels determined for arachidonic acid metabolites, vascular NO levels were reduced in all groups as a result of the chronic UCMS protocol, whereas vascular production of H2O2 was increased. The extent of these differences in dilator metabolite levels between control and UCMS conditions was greater in male and OVX female rats than in female rats, in which the changes in NO levels were not significantly different, whereas the increase in H2O2 levels was comparable to that in male and OVX female rats after 8 wk of UCMS.

Fig. 13.

Vascular production of nitric oxide (NO; A) and H2O2 (B) in male, female, and ovariectomized (OVX) female rats under control conditions and after 8 wk of unpredictable chronic mild stress (UCMS). Data are presented as the slope of NO or H2O2 production in response to increasing concentrations of methacholine (Mch). Values are means ± SE; n = 6 for each group. *P < 0.05 vs. control conditions; †P < 0.05 vs. UCMS male rats.

DISCUSSION

Given the growing prevalence of clinical depression and the striking correlation between depressive symptoms and poor cardiovascular outcomes, determining the mechanistic links between these conditions and how this detrimental relationship can be broken is a critical area for ongoing investigation. The major finding of the present study was that imposition of the UCMS protocol in rats resulted in a significant impairment in endothelium-dependent dilation in the conduit and cerebral resistance vasculature. Although this response was present in male and female rats, vascular reactivity in female rats was protected after UCMS, such that vascular endothelial function was maintained to a greater extent, despite a depressive state that was more severe. The protective effect in female rats appears to have been dependent on the maintenance of a normal sex hormone profile, as OVX surgery before UCMS abolished the protective effect and resulted in vascular outcomes virtually identical to those in male rats. The vascular protection from UCMS in female rats appears to reflect a superior maintenance of endothelial function, with more normal levels of NO and H2O2 as well as the arachidonic acid metabolites PGI2 and TxA2. While previous studies have clearly demonstrated that the imposition of severe depressive symptoms in rats (3, 12) or mice (22, 49) results in impairments in vascular reactivity, the specific mechanisms linking the condition to the vascular outcome have remained somewhat elusive. The results of the present study add to our understanding of these relationships, providing support to the concept that a major contributor to the links between chronic stress/depressive symptoms and vascular dysfunction is mediated through the genesis of a prooxidant and proinflammatory condition that compromises the vascular environment.

Effects of UCMS on Vasoactive Metabolite Levels

On the basis of the present and previous findings, the proinflammatory and prooxidant conditions that are created by the UCMS protocol result in a decline of vascular NO levels and an elevation of H2O2 production, presumably from the dismutation reaction of superoxide (36). While this outcome clearly will reduce the veracity of any vascular responses that are dependent on the production and actions of NO, it could also reflect a compensatory response resulting in the increase in H2O2 acting as an evolving dilator pathway to maintain vascular function to the extent possible (13, 14). From the perspective of arachidonic acid metabolism, the decline in PGI2 production and shift toward an increase in TxA2 production have been previously demonstrated in other models of chronic disease where an increased oxidant and inflammatory environment is created (20, 25, 56, 59); this would clearly have negative implications not only for regulating tone in the resistance vasculature but also for increasing the risk for atherosclerotic lesions in larger arteries (39) and for processes associated with chronic inflammation and leukocyte adhesion in the venular/venous circulation (28, 30).

The ability to maintain a superior profile of vasoactive metabolite production from the vascular endothelium appears to contribute significantly to the protective effect on vascular dysfunction in emale rats after 8 wk of UCMS. Although the depressive symptoms and resulting endocrine profile were manifested to a greater extent in female rats than male rats, female rats exhibited an ability to compensate for this difference and, for the increased oxidant and inflammatory stress, to better maintain vascular reactivity, apparently the result of a greater ability to maintain the “normal” profile of endothelium-derived vasoactive metabolites. This can be readily seen in the data shown in Figs. 11 and 12, where change in the levels of specific metabolites between control conditions and after UCMS in male rats was attenuated in female rats for all four metabolites, a response that was well associated with the improved vascular reactivity. Elimination of the protective effect on vascular function in OVX female rats subjected to the UCMS protocol suggests that the beneficial effect was dependent on a normal female sex hormone profile. The importance of these hormones, particularly estrogen or its most common form, 17β-estradiol (7), in maintaining a protective effect on cardiovascular health has been well established through multiple efforts spanning the spectrum of translational research (29, 33, 47, 53). While the specific nature of these mechanisms, their relative importance, or how they may interact to produce an integrative outcome remain an area of active investigation, a few major themes of relevance to the present study, including the beneficial impact of estrogen on the ability of the vascular endothelium to directly promote the bioavailability of NO, PGI2, and, potentially, other dilator metabolites (33, 35) as well as the ability of estrogen to blunt a prooxidant or proinflammatory environment (29, 51) have emerged. Other issues of potential importance, including the generation and release of hydrogen sulfide (58), the beneficial impact of estrogen on endothelial cell maintenance and repair (34), or actions mediated via G protein-coupled receptor 30 (7), also represent routes through which circulating estrogen levels could impact vascular health.

While the impact of OVX on the mediators of dilator reactivity is complex and issues such as timing, the vascular bed, and the experimental approach must be considered, the effects of OVX on the role of EDHF in vascular reactivity have been especially interesting. While previous studies have determined that OVX can have divergent effects on EDHF and its efficacy (4, 5, 26), recent studies have provided compelling evidence that the contribution of EDHF to vasodilation may be impaired after OVX as a result of alterations in gap junctional effectiveness due to impaired expression of connexin40 and connexin43 (37, 42), although NO-based dilation may have remained intact (42, 57). When taken in the context of the data from the present study, a disruption of EDHF efficacy may have contributed to the impaired dilation response in healthy OVX animals (Fig. 5A), despite a relatively normal level of agonist-induced NO production (Fig. 13A).

Timing and Impact of OVX

It is important to note that the results of this study, in the context of postmenopausal female cardiovascular health, should be interpreted with caution, as the present results reflect the impact of early (between 5 and 6 wk of age) OVX rather than natural alterations to sex hormone profiles that are associated with aging. In addition, the results of the present study clearly suggest that OVX itself may have had an impact on some markers of cardiovascular disease risk, including an increase in insulin resistance and an elevation of some markers of inflammation (primarily, the balance between TNF-α and IL-6). However, there were no consistent effects of OVX on body mass, arterial pressure, blood lipid profiles, or indexes of oxidant stress. Some of the loss of the vascular protection from UCMS together with OVX may have reflected modest increases in insulin resistance and inflammation. Further studies are required to more clearly elucidate the respective roles of OVX-based changes in sex hormones and cardiovascular disease risk factors in terms of their contribution to the loss of vascular protection with UCMS in females.

Integration of Vascular Dysfunction and Depressive Symptoms

A major question arises from the present results: How are chronic stress and depression linked to elevated vascular disease risk? It has been well established that clinical depression is associated with increased hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity and that patients with clinical depression frequently present with increased circulating cortisol levels as a marker of chronic stress (44). However, cortisol has generally been considered to be anti-inflammatory (45), and this can present a challenging, although not uncommon, condition, wherein individuals suffering from chronic depression present with high levels of inflammation attributed to a variety of sources (10), with the aggregate condition of considerably elevated risk for negative health outcomes. A recent study has provided compelling evidence that the inducible form of cyclooxygenase (cyclooxygenase-2), which may be largely responsible for enhanced TxA2 production, is strongly associated with the development and severity of some models of clinical depression (52). Additionally, chronic stress modifies autonomic sympathovagal balance, whereby sympathetic nerve activity and blunted vagal tone, conditions known to contribute to a proinflammatory status (24) as well as vascular dysregulation and development of cardiovascular disease (16), prevail. Future studies should elucidate the interactive effects of sex, UCMS, and sympathetic nerve activity on systemic inflammation, cardiovascular dysregulation, and depressive symptoms. It can be speculated that cortisol, reflecting an environment of chronic stress, may act as an anti-inflammatory agent but that this effect becomes overwhelmed in the face of persistent stress. The growing prooxidant and proinflammatory condition, which can be better tolerated in female rats than male (or OVX female) rats, results in a severe alteration in endothelial function and abrogation of endothelium-dependent vascular control.

Conclusions

We have provided evidence suggesting that imposition of chronic stress and creation of depressive symptoms in otherwise healthy rats lead to impaired vasodilator reactivity at the level of the conduit (aorta) artery and cerebral resistance vasculature. Vascular protection against UCMS that is dependent on normal sex hormone levels (as it was abolished by OVX) better maintains dilator reactivity and metabolite levels in female than male or OVX female rats after UCMS. While the present study provides evidence that the impaired dilator reactivity may reflect lowered NO levels and a reduced PGI2/TxA2 balance with UCMS, additional studies are warranted to determine the levels of other vasoactive metabolites that may contribute to altered vascular function under these conditions.

GRANTS

This work was supported by American Heart Association Grants IRG 14330015, PRE 16850005, and EIA 0740129N, National Center for Research Resources Grant RR-2865AR, and Canadian Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council Grant R4081A03.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.D.B., S.H., S.F., and J.C.F. conceived and designed research; S.D.B., K.C.L., and J.C.F. performed experiments; S.D.B., S.H., P.D.C., S.M., S.F., D.N.J., and J.C.F. analyzed data; S.D.B., S.H., P.D.C., S.M., K.C.L., S.F., J.K.S., D.N.J., and J.C.F. interpreted results of experiments; S.D.B., S.H., P.D.C., S.M., K.C.L., S.F., J.K.S., D.N.J., and J.C.F. edited and revised manuscript; S.D.B., S.H., P.D.C., S.M., K.C.L., S.F., J.K.S., D.N.J., and J.C.F. approved final version of manuscript; S.F., D.N.J., and J.C.F. drafted manuscript; J.C.F. prepared figures.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank to Dr. Shyla C. Stanley for expertise and skill in data collection.

REFERENCES

- 1.Almeida J, Duarte JO, Oliveira LA, Crestani CC. Effects of nitric oxide synthesis inhibitor or fluoxetine treatment on depression-like state and cardiovascular changes induced by chronic variable stress in rats. Stress 18: 462–474, 2015. doi: 10.3109/10253890.2015.1038993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baumbach GL, Hajdu MA. Mechanics and composition of cerebral arterioles in renal and spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 21: 816–826, 1993. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.21.6.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bayramgurler D, Karson A, Yazir Y, Celikyurt IK, Kurnaz S, Utkan T. The effect of etanercept on aortic nitric oxide-dependent vasorelaxation in an unpredictable chronic, mild stress model of depression in rats. Eur J Pharmacol 710: 67–72, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burger NZ, Kuzina OY, Osol G, Gokina NI. Estrogen replacement enhances EDHF-mediated vasodilation of mesenteric and uterine resistance arteries: role of endothelial cell Ca2+. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 296: E503–E512, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90517.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caliman IF, Lamas AZ, Dalpiaz PL, Medeiros AR, Abreu GR, Figueiredo SG, Gusmão LN, Andrade TU, Bissoli NS. Endothelial relaxation mechanisms and oxidative stress are restored by atorvastatin therapy in ovariectomized rats. PLoS One 8: e80892, 2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention BRFSS Prevalence & Trends Data. Chronic Health Indicators. Depression. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/brfssprevalence/index.html [28 August 2017].

- 7.Chakrabarti S, Morton JS, Davidge ST. Mechanisms of estrogen effects on the endothelium: an overview. Can J Cardiol 30: 705–712, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chauvet-Gelinier JC, Bonin B. Stress, anxiety and depression in heart disease patients: a major challenge for cardiac rehabilitation. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 60: 6–12, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dalla C, Antoniou K, Drossopoulou G, Xagoraris M, Kokras N, Sfikakis A, Papadopoulou-Daifoti Z. Chronic mild stress impact: are females more vulnerable? Neuroscience 135: 703–714, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.06.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Danese A, Moffitt TE, Harrington H, Milne BJ, Polanczyk G, Pariante CM, Poulton R, Caspi A. Adverse childhood experiences and adult risk factors for age-related disease: depression, inflammation, and clustering of metabolic risk markers. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 163: 1135–1143, 2009. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.d’Audiffret AC, Frisbee SJ, Stapleton PA, Goodwill AG, Isingrini E, Frisbee JC. Depressive behavior and vascular dysfunction: a link between clinical depression and vascular disease? J Appl Physiol 108: 1041–1051, 2010. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01440.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demirtaş T, Utkan T, Karson A, Yazır Y, Bayramgürler D, Gacar N. The link between unpredictable chronic mild stress model for depression and vascular inflammation? Inflammation 37: 1432–1438, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s10753-014-9867-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El Assar M, Angulo J, Rodríguez-Mañas L. Oxidative stress and vascular inflammation in aging. Free Radic Biol Med 65: 380–401, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ellinsworth DC, Sandow SL, Shukla N, Liu Y, Jeremy JY, Gutterman DD. Endothelium-derived hyperpolarization and coronary vasodilation: diverse and integrated roles of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids, hydrogen peroxide, and gap junctions. Microcirculation 23: 15–32, 2016. doi: 10.1111/micc.12255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Everson-Rose SA, Lewis TT. Psychosocial factors and cardiovascular diseases. Annu Rev Public Health 26: 469–500, 2005. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fisher JP, Young CN, Fadel PJ. Central sympathetic overactivity: maladies and mechanisms. Auton Neurosci 148: 5–15, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franceschelli A, Herchick S, Thelen C, Papadopoulou-Daifoti Z, Pitychoutis PM. Sex differences in the chronic mild stress model of depression. Behav Pharmacol 25: 372–383, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fredricks KT, Liu Y, Rusch NJ, Lombard JH. Role of endothelium and arterial K+ channels in mediating hypoxic dilation of middle cerebral arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 267: H580–H586, 1994. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.267.2.H580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frisbee JC, Brooks SD, Stanley SC, d'Audiffret AC. An unpredictable chronic mild stress protocol for instigating depressive symptoms, behavioral changes and negative health outcomes in rodents. J Vis Exp. In press. doi: 10.3791/53109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frisbee JC, Butcher JT, Frisbee SJ, Olfert IM, Chantler PD, Tabone LE, d’Audiffret AC, Shrader CD, Goodwill AG, Stapleton PA, Brooks SD, Brock RW, Lombard JH. Increased peripheral vascular disease risk progressively constrains perfusion adaptability in the skeletal muscle microcirculation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 310: H488–H504, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00790.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vos T, Barber RM, Bell B, Bertozzi-Villa A, Biryukov S, Bolliger I, Charlson F, Davis A, Degenhardt L, Dicker D, Duan L, Erskine H, Feigin VL, Ferrari AJ, Fitzmaurice C, Fleming T, Graetz N, Guinovart C, Haagsma J, Hansen GM, Hanson SW, Heuton KR, Higashi H, Kassebaum N, Kyu H, Laurie E, Liang X, Lofgren K, Lozano R, MacIntyre MF, Moradi-Lakeh M, Naghavi M, Nguyen G, Odell S, Ortblad K, Roberts DA, Roth GA, Sandar L, Serina PT, Stanaway JD, Steiner C, Thomas B, Vollset SE, Whiteford H, Wolock TM, Ye P, Zhou M, Ãvila MA, Aasvang GM, Abbafati C, Ozgoren AA, Abd-Allah F, Aziz MIA, Abera SF, Aboyans V, Abraham JP, Abraham B, Abubakar I, Abu-Raddad LJ, Abu-Rmeileh NME, Aburto TC, Achoki T, Ackerman IN, Adelekan A, Ademi Z, Adou AK, Adsuar JC, Arnlov J, Agardh EE, Al Khabouri MJ, Alam SS, Alasfoor D, Albittar MI, Alegretti MA, Aleman AV, Alemu ZA, Alfonso-Cristancho R, Alhabib S, Ali R, Alla F, Allebeck P, Allen PJ, AlMazroa MAA, Alsharif U, Alvarez E, Alvis-Guzman N, Ameli O, Amini H, Ammar W, Anderson BO, Anderson HR, Antonio CAT, Anwari P, Apfel H, Arsenijevic VSA, Artaman A, Asghar RJ, Assadi R, Atkins LS, Atkinson C, Badawi A, Bahit MC, Bakfalouni T, Balakrishnan K, Balalla S, Banerjee A, Barker-Collo SL, Barquera S, Barregard L, Barrero LH, Basu S, Basu A, Baxter A, Beardsley J, Bedi N, Beghi E, Bekele T, Bell ML, Benjet C, Bennett DA, Bensenor IM, Benzian H, Bernabe E, Beyene TJ, Bhala N, Bhalla A, Bhutta Z, Bienhoff K, Bikbov B, Abdulhak AB, Blore JD, Blyth FM, Bohensky MA, Basara BB, Borges G, Bornstein NM, Bose D, Boufous S, Bourne RR, Boyers LN, Brainin M, Brauer M, Brayne CEG, Brazinova A, Breitborde NJK, Brenner H, Briggs ADM, Brooks PM, Brown J, Brugha TS, Buchbinder R, Buckle GC, Bukhman G, Bulloch AG, Burch M, Burnett R, Cardenas R, Cabral NL, Nonato IRC, Campuzano JC, Carapetis JR, Carpenter DO, Caso V, Castaneda-Orjuela CA, Catala-Lopez F, Chadha VK, Chang J-C, Chen H, Chen W, Chiang PP, Chimed-Ochir O, Chowdhury R, Christensen H, Christophi CA, Chugh SS, Cirillo M, Coggeshall M, Cohen A, Colistro V, Colquhoun SM, Contreras AG, Cooper LT, Cooper C, Cooperrider K, Coresh J, Cortinovis M, Criqui MH, Crump JA, Cuevas-Nasu L, Dandona R, Dandona L, Dansereau E, Dantes HG, Dargan PI, Davey G, Davitoiu DV, Dayama A, De la Cruz-Gongora V, de la Vega SF, De Leo D, del Pozo-Cruz B, Dellavalle RP, Deribe K, Derrett S, Des Jarlais DC, Dessalegn M, deVeber GA, Dharmaratne SD, Diaz-Torne C, Ding EL, Dokova K, Dorsey ER, Driscoll TR, Duber H, Durrani AM, Edmond KM, Ellenbogen RG, Endres M, Ermakov SP, Eshrati B, Esteghamati A, Estep K, Fahimi S, Farzadfar F, Fay DFJ, Felson DT, Fereshtehnejad S-M, Fernandes JG, Ferri CP, Flaxman A, Foigt N, Foreman KJ, Fowkes FGR, Franklin RC, Furst T, Futran ND, Gabbe BJ, Gankpe FG, Garcia-Guerra FA, Geleijnse JM, Gessner BD, Gibney KB, Gillum RF, Ginawi IA, Giroud M, Giussani G, Goenka S, Goginashvili K, Gona P, de Cosio TG, Gosselin RA, Gotay CC, Goto A, Gouda HN, Guerrant R, Gugnani HC, Gunnell D, Gupta R, Gupta R, Gutierrez RA, Hafezi-Nejad N, Hagan H, Halasa Y, Hamadeh RR, Hamavid H, Hammami M, Hankey GJ, Hao Y, Harb HL, Haro JM, Havmoeller R, Hay RJ, Hay S, Hedayati MT, Pi IBH, Heydarpour P, Hijar M, Hoek HW, Hoffman HJ, Hornberger JC, Hosgood HD, Hossain M, Hotez PJ, Hoy DG, Hsairi M, Hu H, Hu G, Huang JJ, Huang C, Huiart L, Husseini A, Iannarone M, Iburg KM, Innos K, Inoue M, Jacobsen KH, Jassal SK, Jeemon P, Jensen PN, Jha V, Jiang G, Jiang Y, Jonas JB, Joseph J, Juel K, Kan H, Karch A, Karimkhani C, Karthikeyan G, Katz R, Kaul A, Kawakami N, Kazi DS, Kemp AH, Kengne AP, Khader YS, Khalifa SEAH, Khan EA, Khan G, Khang Y-H, Khonelidze I, Kieling C, Kim D, Kim S, Kimokoti RW, Kinfu Y, Kinge JM, Kissela BM, Kivipelto M, Knibbs L, Knudsen AK, Kokubo Y, Kosen S, Kramer A, Kravchenko M, Krishnamurthi RV, Krishnaswami S, Defo BK, Bicer BK, Kuipers EJ, Kulkarni VS, Kumar K, Kumar GA, Kwan GF, Lai T, Lalloo R, Lam H, Lan Q, Lansingh VC, Larson H, Larsson A, Lawrynowicz AEB, Leasher JL, Lee J-T, Leigh J, Leung R, Levi M, Li B, Li Y, Li Y, liang J, Lim S, Lin H-H, Lind M, Lindsay MP, Lipshultz SE, Liu S, Lloyd BK, Ohno SL, Logroscino G, Looker KJ, Lopez AD, Lopez-Olmedo N, Lortet-Tieulent J, Lotufo PA, Low N, Lucas RM, Lunevicius R, Lyons RA, Ma J, Ma S, Mackay MT, Majdan M, Malekzadeh R, Mapoma CC, Marcenes W, March LM, Margono C, Marks GB, Marzan MB, Masci JR, Mason-Jones AJ, Matzopoulos RG, Mayosi BM, Mazorodze TT, McGill NW, McGrath JJ, McKee M, McLain A, McMahon BJ, Meaney PA, Mehndiratta MM, Mejia-Rodriguez F, Mekonnen W, Melaku YA, Meltzer M, Memish ZA, Mensah G, Meretoja A, Mhimbira FA, Micha R, Miller TR, Mills EJ, Mitchell PB, Mock CN, Moffitt TE, Ibrahim NM, Mohammad KA, Mokdad AH, Mola GL, Monasta L, Montico M, Montine TJ, Moore AR, Moran AE, Morawska L, Mori R, Moschandreas J, Moturi WN, Moyer M, Mozaffarian D, Mueller UO, Mukaigawara M, Murdoch ME, Murray J, Murthy KS, Naghavi P, Nahas Z, Naheed A, Naidoo KS, Naldi L, Nand D, Nangia V, Narayan KMV, Nash D, Nejjari C, Neupane SP, Newman LM, Newton CR, Ng M, Ngalesoni FN, Nhung NT, Nisar MI, Nolte S, Norheim OF, Norman RE, Norrving B, Nyakarahuka L, Oh IH, Ohkubo T, Omer SB, Opio JN, Ortiz A, Pandian JD, Panelo CIA, Papachristou C, Park E-K, Parry CD, Caicedo AJP, Patten SB, Paul VK, Pavlin BI, Pearce N, Pedraza LS, Pellegrini CA, Pereira DM, Perez-Ruiz FP, Perico N, Pervaiz A, Pesudovs K, Peterson CB, Petzold M, Phillips MR, Phillips D, Phillips B, Piel FB, Plass D, Poenaru D, Polanczyk GV, Polinder S, Pope CA, Popova S, Poulton RG, Pourmalek F, Prabhakaran D, Prasad NM, Qato D, Quistberg DA, Rafay A, Rahimi K, Rahimi-Movaghar V, Rahman S, Raju M, Rakovac I, Rana SM, Razavi H, Refaat A, Rehm J, Remuzzi G, Resnikoff S, Ribeiro AL, Riccio PM, Richardson L, Richardus JH, Riederer AM, Robinson M, Roca A, Rodriguez A, Rojas-Rueda D, Ronfani L, Rothenbacher D, Roy N, Ruhago GM, Sabin N, Sacco RL, Ksoreide K, Saha S, Sahathevan R, Sahraian MA, Sampson U, Sanabria JR, Sanchez-Riera L, Santos IS, Satpathy M, Saunders JE, Sawhney M, Saylan MI, Scarborough P, Schoettker B, Schneider IJC, Schwebel DC, Scott JG, Seedat S, Sepanlou SG, Serdar B, Servan-Mori EE, Shackelford K, Shaheen A, Shahraz S, Levy TS, Shangguan S, She J, Sheikhbahaei S, Shepard DS, Shi P, Shibuya K, Shinohara Y, Shiri R, Shishani K, Shiue I, Shrime MG, Sigfusdottir ID, Silberberg DH, Simard EP, Sindi S, Singh JA, Singh L, Skirbekk V, Sliwa K, Soljak M, Soneji S, Soshnikov SS, Speyer P, Sposato LA, Sreeramareddy CT, Stoeckl H, Stathopoulou VK, Steckling N, Stein MB, Stein DJ, Steiner TJ, Stewart A, Stork E, Stovner LJ, Stroumpoulis K, Sturua L, Sunguya BF, Swaroop M, Sykes BL, Tabb KM, Takahashi K, Tan F, Tandon N, Tanne D, Tanner M, Tavakkoli M, Taylor HR, Te Ao BJ, Temesgen AM, Have MT, Tenkorang EY, Terkawi AS, Theadom AM, Thomas E, Thorne-Lyman AL, Thrift AG, Tleyjeh IM, Tonelli M, Topouzis F, Towbin JA, Toyoshima H, Traebert J, Tran BX, Trasande L, Trillini M, Truelsen T, Trujillo U, Tsilimbaris M, Tuzcu EM, Ukwaja KN, Undurraga EA, Uzun SB, van Brakel WH, van de Vijver S, Dingenen RV, van Gool CH, Varakin YY, Vasankari TJ, Vavilala MS, Veerman LJ, Velasquez-Melendez G, Venketasubramanian N, Vijayakumar L, Villalpando S, Violante FS, Vlassov VV, Waller S, Wallin MT, Wan X, Wang L, Wang JL, Wang Y, Warouw TS, Weichenthal S, Weiderpass E, Weintraub RG, Werdecker A, Wessells KRR, Westerman R, Wilkinson JD, Williams HC, Williams TN, Woldeyohannes SM, Wolfe CDA, Wong JQ, Wong H, Woolf AD, Wright JL, Wurtz B, Xu G, Yang G, Yano Y, Yenesew MA, Yentur GK, Yip P, Yonemoto N, Yoon S-J, Younis M, Yu C, Kim KY, Zaki MES, Zhang Y, Zhao Z, Zhao Y, Zhu J, Zonies D, Zunt JR, Salomon JA, Murray CJL; Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators . Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 386: 743–800, 2015. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60692-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Golbidi S, Frisbee JC, Laher I. Chronic stress impacts the cardiovascular system: animal models and clinical outcomes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 308: H1476–H1498, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00859.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grippo AJ, Francis J, Beltz TG, Felder RB, Johnson AK. Neuroendocrine and cytokine profile of chronic mild stress-induced anhedonia. Physiol Behav 84: 697–706, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Halaris A. Inflammation-associated co-morbidity between depression and cardiovascular disease. Curr Top Behav Neurosci 31: 45–70, 2017. doi: 10.1007/7854_2016_28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hodnett BL, Dearman JA, Carter CB, Hester RL. Attenuated PGI2 synthesis in obese Zucker rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 296: R715–R721, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90330.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang A, Wu Y, Sun D, Koller A, Kaley G. Effect of estrogen on flow-induced dilation in NO deficiency: role of prostaglandins and EDHF. J Appl Physiol 91: 2561–2566, 2001. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.6.2561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Isingrini E, Belzung C, d’Audiffret A, Camus V. Early and late-onset effect of chronic stress on vascular function in mice: a possible model of the impact of depression on vascular disease in aging. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 19: 335–346, 2011. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318202bc42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katagiri H, Ito Y, Ito S, Murata T, Yukihiko S, Narumiya S, Watanabe M, Majima M. TNF-α induces thromboxane receptor signaling-dependent microcirculatory dysfunction in mouse liver. Shock 30: 463–467, 2008. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181673f54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim JK, Levin ER. Estrogen signaling in the cardiovascular system. Nucl Recept Signal 4: e013, 2006. doi: 10.1621/nrs.04013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim MH, Granger DN, Harris NR. Mediators of CD18/P-selectin-dependent constriction of venule-paired arterioles in hypercholesterolemia. Microvasc Res 73: 150–155, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koledova VV, Khalil RA. Sex hormone replacement therapy and modulation of vascular function in cardiovascular disease. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 5: 777–789, 2007. doi: 10.1586/14779072.5.4.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuehner C. Gender differences in unipolar depression: an update of epidemiological findings and possible explanations. Acta Psychiatr Scand 108: 163–174, 2003. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.00204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.LeBlanc AJ, Reyes R, Kang LS, Dailey RA, Stallone JN, Moningka NC, Muller-Delp JM. Estrogen replacement restores flow-induced vasodilation in coronary arterioles of aged and ovariectomized rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 297: R1713–R1723, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00178.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leen LL, Filipe C, Billon A, Garmy-Susini B, Jalvy S, Robbesyn F, Daret D, Allières C, Rittling SR, Werner N, Nickenig G, Deutsch U, Duplàa C, Dufourcq P, Lenfant F, Desgranges C, Arnal JF, Gadeau AP. Estrogen-stimulated endothelial repair requires osteopontin. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 28: 2131–2136, 2008. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.167965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lekontseva O, Chakrabarti S, Jiang Y, Cheung CC, Davidge ST. Role of neuronal nitric-oxide synthase in estrogen-induced relaxation in rat resistance arteries. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 339: 367–375, 2011. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.183798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liochev SI, Fridovich I. The effects of superoxide dismutase on H2O2 formation. Free Radic Biol Med 42: 1465–1469, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu MY, Hattori Y, Sato A, Ichikawa R, Zhang XH, Sakuma I. Ovariectomy attenuates hyperpolarization and relaxation mediated by endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor in female rat mesenteric artery: a concomitant decrease in connexin-43 expression. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 40: 938–948, 2002. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200212000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu Y, Fredricks KT, Roman RJ, Lombard JH. Response of resistance arteries to reduced Po2 and vasodilators during hypertension and elevated salt intake. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 273: H869–H877, 1997. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.2.H869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maree AO, Fitzgerald DJ. Variable platelet response to aspirin and clopidogrel in atherothrombotic disease. Circulation 115: 2196–2207, 2007. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.675991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matchkov VV, Kravtsova VV, Wiborg O, Aalkjaer C, Bouzinova EV. Chronic selective serotonin reuptake inhibition modulates endothelial dysfunction and oxidative state in rat chronic mild stress model of depression. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 309: R814–R823, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00337.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Musliner KL, Munk-Olsen T, Eaton WW, Zandi PP. Heterogeneity in long-term trajectories of depressive symptoms: patterns, predictors and outcomes. J Affect Disord 192: 199–211, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nawate S, Fukao M, Sakuma I, Soma T, Nagai K, Takikawa O, Miwa S, Kitabatake A. Reciprocal changes in endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor- and nitric oxide-system in the mesenteric artery of adult female rats following ovariectomy. Br J Pharmacol 144: 178–189, 2005. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nies AS. Prostaglandins and the control of the circulation. Clin Pharmacol Ther 39: 481–488, 1986. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1986.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pariante CM, Lightman SL. The HPA axis in major depression: classical theories and new developments. Trends Neurosci 31: 464–468, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pariante CM. Why are depressed patients inflamed? A reflection on 20 years of research on depression, glucocorticoid resistance and inflammation. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 27: 554–559, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2017.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Plante GE. Depression and cardiovascular disease: a reciprocal relationship. Metabolism 54 Suppl 1: 45–48, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Regitz-Zagrosek V. Therapeutic implications of the gender-specific aspects of cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov 5: 425–438, 2006. doi: 10.1038/nrd2032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rincón-Cortés M, Grace AA. Sex-dependent effects of stress on immobility behavior and VTA dopamine neuron activity: modulation by ketamine. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 20: 823–832, 2017. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyx048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stanley SC, Brooks SD, Butcher JT, d’Audiffret AC, Frisbee SJ, Frisbee JC. Protective effect of sex on chronic stress- and depressive behavior-induced vascular dysfunction in BALB/cJ mice. J Appl Physiol 117: 959–970, 2014. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00537.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stedenfeld KA, Clinton SM, Kerman IA, Akil H, Watson SJ, Sved AF. Novelty-seeking behavior predicts vulnerability in a rodent model of depression. Physiol Behav 103: 210–216, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Strehlow K, Rotter S, Wassmann S, Adam O, Grohé C, Laufs K, Böhm M, Nickenig G. Modulation of antioxidant enzyme expression and function by estrogen. Circ Res 93: 170–177, 2003. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000082334.17947.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Su KP, Huang SY, Peng CY, Lai HC, Huang CL, Chen YC, Aitchison KJ, Pariante CM. Phospholipase A2 and cyclooxygenase 2 genes influence the risk of interferon-α-induced depression by regulating polyunsaturated fatty acids levels. Biol Psychiatry 67: 550–557, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thomas G, Ito K, Zikic E, Bhatti T, Han C, Ramwell PW. Specific inhibition of the contraction of the rat aorta by estradiol 17β. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 273: 1544–1550, 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Willner P. The chronic mild stress (CMS) model of depression: history, evaluation and usage. Neurobiol Stress 6: 78–93, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2016.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Willner P. Validity, reliability and utility of the chronic mild stress model of depression: a 10-year review and evaluation. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 134: 319–329, 1997. doi: 10.1007/s002130050456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xiang L, Naik JS, Hodnett BL, Hester RL. Altered arachidonic acid metabolism impairs functional vasodilation in metabolic syndrome. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 290: R134–R138, 2006. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00295.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xu HL, Santizo RA, Baughman VL, Pelligrino DA. Nascent EDHF-mediated cerebral vasodilation in ovariectomized rats is not induced by eNOS dysfunction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285: H2045–H2053, 2003. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00439.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhou K, Gao Q, Zheng S, Pan S, Li P, Suo K, Simoncini T, Wang T, Fu X. 17β-Estradiol induces vasorelaxation by stimulating endothelial hydrogen sulfide release. Mol Hum Reprod 19: 169–176, 2013. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gas044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zou MH. Peroxynitrite and protein tyrosine nitration of prostacyclin synthase. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat 82: 119–127, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]