Abstract

The capacity of the cerebrovasculature to buffer changes in blood pressure (BP) is crucial to prevent stroke, the incidence of which is three- to fourfold elevated after spinal cord injury (SCI). Disruption of descending sympathetic pathways within the spinal cord due to cervical SCI may result in impaired cerebrovascular buffering. Only linear analyses of cerebrovascular buffering of BP, such as transfer function, have been used in SCI research. This approach does not account for inherent nonlinearity and nonstationarity components of cerebrovascular regulation, often depends on perturbations of BP to increase the statistical power, and does not account for the influence of arterial CO2 tension. Here, we used a nonlinear and nonstationary analysis approach termed wavelet decomposition analysis (WDA), which recently identified novel sympathetic influences on cerebrovascular buffering of BP occurring in the ultra-low-frequency range (ULF; 0.02–0.03Hz). WDA does not require BP perturbations and can account for influences of CO2 tension. Supine resting beat-by-beat BP (Finometer), middle cerebral artery blood velocity (transcranial Doppler), and end-tidal CO2 tension were recorded in cervical SCI (n = 14) and uninjured (n = 16) individuals. WDA revealed that cerebral blood flow more closely follows changes in BP in the ULF range (P = 0.0021, Cohen’s d = 0.89), which may be interpreted as an impairment in cerebrovascular buffering of BP. This persisted after accounting for CO2. Transfer function metrics were not different in the ULF range, but phase was reduced at 0.07–0.2 Hz (P = 0.03, Cohen’s d = 0.31). Sympathetically mediated cerebrovascular buffering of BP is impaired after SCI, and WDA is a powerful strategy for evaluating cerebrovascular buffering in clinical populations.

Keywords: cerebral autoregulation, cerebral blood flow, cerebral pressure-flow relationships, paraplegia, tetraplegia, wavelet decomposition analysis

INTRODUCTION

The capacity to maintain stable cerebral blood flow (CBF) in the face of changing blood pressure (BP; i.e., cerebrovascular buffering1) is a crucial mechanism evolving with the teleological purpose of preventing cerebral hyper- and hypoperfusion. Appropriate CBF is crucial, as when the brain is overperfused there is risk of cerebral hemorrhage (43), posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (35), and deleterious cerebrovascular remodeling (28). On the opposite end of the spectrum, when the brain is underperfused, one risks ischemia, cognitive decline (5, 17, 27), and loss of consciousness (20, 22). The mechanism(s) responsible for cerebrovascular buffering of BP remain elusive but certainly require sophisticated and redundant control from the sympathetic nervous system as well as local myogenic regulation, in addition to the intrinsic compliant nature of the cerebrovasculature (46) and the overarching control of arterial CO2 tension (1, 45).

Cerebrovascular health and function are impaired after spinal cord injury (SCI), which likely underlies the three- to fourfold increased risk/odds of stroke in the population (4, 48) as well as widespread orthostatic intolerance (22) and cognitive decline (27). Several factors may contribute to the reduced cerebrovascular health and function after SCI, which include high rates of diabetes, reduced ability to physical exercise, and repetitive cerebral hypoperfusion due to baroreflex dysfunction (3, 6, 20, 21, 23). Current strategies used to evaluate cerebrovascular buffering are not appropriate in many clinical populations, such as those with SCI, as they require the induction of large perturbations in BP (through either gravitational challenges or pharmacological interventions) in individuals who already suffer from life-threatening instability in BP (7, 40) and do not account for the potentially differing influences of arterial CO2 tension on the cerebrovasculature after SCI (47). Furthermore, the previously applied approaches assume a linear relationship between BP and CBF using transfer function analysis (9) and/or that BP and CBF behave in a stationary manner and can be analyzed using nonvarying shaped ridge functions (39). These approaches are likely suboptimal. For example, it is known that the cerebrovascular buffering of BP is complex, with multiple regulatory mechanisms, and that these mechanisms behave in a nonlinear and nonstationary manner (17, 30, 41, 42) and are influenced by arterial CO2 tension (1).

Recently, a new approach to evaluate cerebrovascular buffering has emerged based on wavelet decomposition analysis (WDA) of spontaneous BP and CBF fluctuations (30). This approach is designed to examine cerebrovascular buffering while identifying the nonlinear and nonstationary relationships between BP and CBF (19, 31). An additional benefit of this approach is that it can account for influences from arterial CO2 tension (1, 47). Furthermore, this approach is also arguably more clinically relevant, in that it does not involve BP perturbations for improved accuracy/statistical power but instead requires only resting steady-state hemodynamic recordings (30). It has been recently demonstrated that WDA is capable of detecting alterations in cerebrovascular buffering due to pharmacological blockade of the sympathetic nervous system in healthy individuals, when standard linear and stationary approaches were not (30). This study demonstrated that the sympathetic nervous system impacts cerebrovascular buffering of BP in the ultra-low-frequency (ULF) range of 0.02–0.03 Hz (30, 31).

To explore the hypothesis that SCI results in impaired cerebrovascular buffering, we implemented WDA on BP and CBF in individuals with cervical SCI and uninjured control subjects. As disrupted supraspinal sympathetic control of the cerebrovasculature occurs after high-level SCI (26), we reasoned that WDA would reveal impaired cerebrovascular buffering in the ultra-low 0.02- to 0.03-Hz range in individuals with SCI, and this would persist after accounting for the influence of CO2 tension. We also hypothesized that the standard linear transfer function analysis between BP and CBF would not detect differences between SCI and uninjured groups in the ULF range of 0.02–0.03 Hz.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All participants with SCI had sustained a cervical SCI [all participants were American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale (AIS) A or B, with the exception of three AIS C participants and one AIS D participants]. All injuries took place at least 1 yr before the testing (range: 1.6–44 yr since injury; see Table 1). Participants with SCI (n = 14, 5 women and 9 men) and uninjured individuals (n = 16, 7 women and 9 men) were age matched and were instructed to abstain from exercise and alcohol for 24 h before testing and caffeine on the day of testing and to only have a small meal (e.g., a small yogurt) ∼1 h before the testing. Nine participants with SCI were drug free, whereas two participants were taking Baclofen (10 mg/day) and three participants were prescribed Lyrica (2 × 300 mg/day), Ventolin, or Alvesco for asthma (one inhalation in morning) for each. Similarly, 13 uninjured participants were drug free, whereas three participants were taking Alvesco (one inhalation in the morning), acetylsalicylic acid (100 mg/day), or Euthyrox (100 g/day), respectively. All participants provided written informed consent. This study was approved by the clinical research ethics board of School of Medicine in Split, University of Split (Split, Croatia). Participants were tested over a 1-h protocol that consisted of at least 15 min resting in the supine position while being outfitted with the assessment equipment. Next, 10 min of resting data were collected for analysis. Two subjects had motion arteficts over the course of data collections and only 6 min of their clean data were used for analyses. For each participant, brachial BP was measured (Dinamap, General Electric Pro 300V2, Tampa, FL) on the left brachial artery each minute throughout the protocol. The following measurements were sampled at 1 kHz using an analog-to-digital converter (Powerlab/16SP ML 795, AD Instruments, Colorado Springs, CO) interfaced with data-acquisition software on a laptop computer (LabChart 8, AD Instruments): beat-by-beat BP via finger photoplethysmography (Finometer PRO, Finapres Medical Systems, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) and the electrocardiogram. Middle cerebral artery (MCA) blood velocity was recorded in the right MCA (ST3 Transcranial Doppler, Spencer Technologies, Redmond, WA) using a 2-MHz probe mounted on the temporal bone and a fitted head strap, according to detailed instructions published elsewhere by our group (22, 27). Systolic BP (SBP) and diastolic BP (DBP) as well as peak MCA blood velocity (MCAvmax) and minimum MCAv (MCAvmin) were used to calculate mean arterial BP as follows: (2 × DBP + SBP)/3 and mean MCA velocity (MCAvmean) = (2 × MCAvmin + MCAvmax)/3, respectively. End-tidal Pco2 () was sampled from a leak-free mouth piece and measured by a gas analyzer (ML206, AD Instruments). Consistent with our previous study (30), the 1-kHz continuous recordings of BP, MCA velocity, and were transformed to beat-to-beat mean arterial pressure (MAP) and MCAvmean values and breath-to-breath followed by cubic-spline interpolation and decimated to 2 Hz. A high-pass fifth-order Butterworth filter with a cutoff frequency of 0.005 Hz was used to remove very slow variations and baseline drift. The occasional artifacts were removed using Grubb’s test. Analyses were done using signal processing software Ensemble (version 1, Elucimed, Wellington, New Zealand) and MATLAB (version R2014b, MATHWORKS, Natick, MA).

Table 1.

Selected demographic information and supine resting physiological data for uninjured individuals and participants with spinal cord injury

| Variable | Uninjured | Spinal Cord Injury | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 43 ± 3 | 43 ± 4 | 0.89 |

| Height, m | 1.8 ± 0.04 | 1.8 ± 0.02 | 0.92 |

| Mass, kg | 81 ± 5 | 71 ± 4 | 0.04 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 25 ± 0.7 | 22 ± 0.8 | 0.007 |

| Years since injury | NA | 20 ± 3 | NA |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 57 ± 2.4 | 59 ± 3.0 | 0.52 |

| Mean arterial pressure, mmHg | 84 ± 2.1 | 77 ± 2.8 | 0.21 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 116 ± 3.6 | 105 ± 3.6 | 0.05 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 69 ± 1.7 | 63 ± 2.8 | 0.08 |

| Mean MCA blood velocity, cm/s | 57 ± 3.3 | 54 ± 2.8 | 0.52 |

| Maximum MCA blood velocity, cm/s | 89 ± 4.9 | 85 ± 4.3 | 0.51 |

| Minimum MCA blood velocity, cm/s | 41 ± 2.7 | 39 ± 2.3 | 0.50 |

| End-tidal Po2, mmHg | 39 ± 1.1 | 40 ± 1.3 | 0.42 |

| Breathing rate, breaths/min | 14 ± 0.6 | 15 ± 0.4 | 0.55 |

Values are means ± SE. MCA, middle cerebral artery; NA, not applicable. P values were not corrected for multiple comparisons.

Wavelet decomposition analysis.

As described in Ref. 30, the wavelet transform of a signal x(t) is given by the following equation:

| (1) |

where a is the scale creating translation and dilation of the complex mother wavelet ψ (Morlet wavelet in this study), which is given by the following equation:

where fb and fc are the bandwidth parameter and center frequency, respectively, which are both set to 1 in this study. The time index t0 moving along a time series extracts local features of the signal x(t) The scale parameter a is related to fc as follows:

where fa is a pseudo-frequency and δt is the sampling period. The wavelet transform Wx(a,t0) can be used to derive the instantaneous phase of signal x(t) as follows:

The phase difference between MAP and MCAvmean is given by the following equation:

where ϕB and ϕM are wavelet-based instantaneous phases of MAP and MCAvmean, respectively. The phase synchrony index (PSI) is given by the following equation:

| (2) |

where N is the data length. The PSI values range in the interval 0 < γ < 1. The smallest value of PSI (γ = 0) represents a uniform distribution of wavelet phase differences between MAP and MCAvmean (i.e., MAP and MCAvmean are not synchronized), which may indicate that cerebrovascular buffering of BP is pronounced. A large PSI value (γ = 1) denotes perfect synchronization (i.e., changes in MAP and MCAvmean are occurring at an identical phase angle), indicating MCAvmean closely follows MAP, and that cerebrovascular buffering of BP is not occurring.

After correction, the phase difference becomes as follows:

| (3) |

where ϕBC is the wavelet-based phase difference between MAP and and ψCM and ψBM are transfer function-based phase differences of -MCAvmean and MAP-MCAvmean, respectively, i.e., and . HCM and HBM are the transfer functions of -MCAvmean and MAP-MCAvmean, respectively. WC and WB are the wavelet coefficients using Eq. 1 for and MAP, respectively. In Eq. 3, the second term is the identified phase error caused by .

Transfer function analysis.

As previously described (30), the transfer function analysis metrics (i.e., coherence, gain and phase) were derived using the following equation:

where SBM is the cross-spectrum between MAP and MCAvmean and SBB is the auto-spectrum of MAP. The power spectral density (PSD) and mean values of transfer function metrics were calculated in traditional very-low-frequency (VLF; 0.02–0.07 Hz), low-frequency (LF; 0.07–0.2 Hz), and high-frequency (HF; 0.2–0.4 Hz) ranges. We did not adjust or control for coherence while averaging metrics across these frequency ranges.

Statistics.

The normality of data was verified using a Shapiro-Wilk test. Transfer function coherence and phase were r-to-z and arcsine transformed, respectively, to obtain asymptotic distributions. For ease of interpretation and analysis, all values are presented here in standard units. Following the assessment of variance homogeneity, participants with SCI and uninjured individuals were compared using parametric (i.e., independent-samples t-tests) or nonparametric comparisons (i.e., related-samples Wilcoxon signed-rank test or independent-samples Mann-Whitney U-test) with Bonferroni corrections. Significance was set a priori at P < 0.05 unless otherwise stated. Values are represented as means ± SE unless otherwise stated.

RESULTS

Physiological characteristics of the two groups are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences between groups for maximum, minimum, or mean blood velocity in the MCA, heart rate, , and breathing rate. In participants with SCI, MAP tended to be reduced (Table 1).

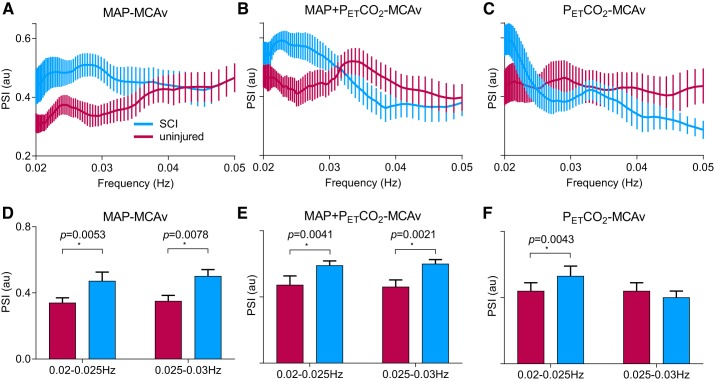

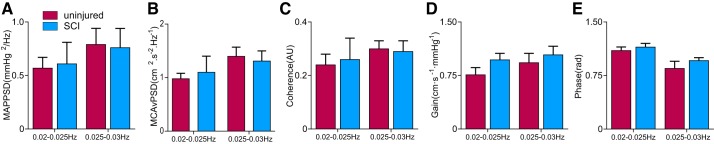

There was greater PSI between MAP and MCAvmean in the ULF ranges (0.02–0.025 and 0.025–0.03 Hz) in the SCI group, indicating impaired capacity for cerebrovascular buffering of MAP (Fig. 1, A and B) (16). Furthermore, participants with SCI had greater PSI between and MCAvmean at 0.02–0.025 Hz, indicating a more direct influence of on MCAvmean after SCI. None of the PSD or transfer function analysis metrics were different between groups in the ULF ranges (0.02–0.025 and 0.025–0.03 Hz; Fig. 2). In terms of traditional frequency ranges, the PSD for MAP or MCAvmean was not different between groups across VLF or HF ranges; however, MCAvmean PSD was reduced in participants with SCI for the LF range (Table 2). Coherence and gain were not different between groups for any frequency range;, however, the LF phase was reduced in the SCI group (Table 2). The effect size (Cohen’s d) for PSI at 0.02–0.03 Hz was 0.89, and LF transfer function phase effect size was 0.31. As subanalyses, we also compared 1) only participants with motor complete injury (AIS A or B) with control subjects as well as 2) participants with motor complete (AIS A or B) versus incomplete (AIS C or D) injuries. With either of these analyses, the primary outcomes (e.g., PSI or transfer function analysis metrics) did not change.

Fig. 1.

Wavelet decomposition analysis of mean arterial pressure (MAP) and middle cerebral artery (MCA) velocity (MCAv), with and without end-tidal Pco2 () correction, in uninjured individuals and participants with a spinal cord injury (SCI). The group with SCI presented with impaired capacity for cerebrovascular buffering, as indicated by the increased phase synchrony index [PSI; in arbitrary units (au)], in the MCA in the ultra-low-frequency ranges (0.02–0.025 and 0.025–0.03 Hz, A and D). This difference persisted (B and E) after correction for the direct influence that arterial CO2 tension exerted on MCAv (C and F). *Significance at P < 0.05.

Fig. 2.

Power spectrum and transfer function analysis of mean arterial pressure (MAP) and middle cerebral artery velocity (MCAv) in uninjured individuals and participants with a spinal cord injury (SCI). No significant changes were found across ultra-low-frequency ranges (0.02–0.025 and 0.025–0.03 Hz). PSD, power spectral density, AU, arbitrary units.

Table 2.

Power spectrum and transfer function analysis across traditional frequency ranges

| Variable | Uninjured | Spinal Cord Injury | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| VLF MAP PSD, mmHg2/Hz | 2.4 ± 0.5 | 2.1 ± 0.5 | 0.67 |

| LF MAP PSD, mmHg2/Hz | 2.5 ± 1.1 | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 0.38 |

| HF MAP PSD, mmHg2/Hz | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 0.29 |

| VLF MCAvmean PSD, cm2·s−2·Hz−1 | 3.0 ± 0.6 | 2.9 ± 0.6 | 0.51 |

| LF MCAvmean PSD, cm2·s−2·Hz−1 | 2.0 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 0.01 |

| HF MCAvmean PSD, cm2·s−2·Hz−1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.5 | 0.79 |

| VLF coherence, AU | 0.4 ± 0.04 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.41 |

| LF coherence, AU | 0.5 ± 0.04 | 0.4 ± 0.03 | 0.47 |

| HF coherence, AU | 0.6 ± 0.06 | 0.5 ± 0.07 | 0.76 |

| VLF gain, cm·s−1·mmHg−1 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 0.45 |

| LF gain, cm·s−1·mmHg−1 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.25 |

| HF gain, cm·s−1·mmHg−1 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 0.27 |

| VLF phase, radians | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.21 |

| LF phase, radians | 0.7 ± 0.6 | 0.2 ± 0.2 | 0.03 |

| HF phase, radians | 0.2 ± 0.6 | 0.3 ± 0.3 | 0.46 |

Values are means ± SE. VLF, very low frequency (0.02–0.07 Hz); MAP, mean arterial blood pressure; PSD, power spectral density; LF, low frequency (0.07–0.2 Hz); HF, high frequency (0.2–0.4 Hz); MCAvmean, middle cerebral artery mean blood velocity; AU, arbitrary units.

DISCUSSION

Nonlinear and nonstationary cerebrovascular buffering of BP is impaired after sustaining a cervical SCI, which persists after accounting for the cerebrovascular influence of arterial CO2 tension. This supports our hypothesis. That this impairment occurred in the ULF range recently identified to be influenced by the sympathetic nervous system indicates that the impaired capacity for cerebrovascular buffering of BP is likely the result of disrupted supraspinal sympathetic control over the cerebrovasculature (30).

From a clinical perspective, the present data demonstrate that resting BP and CBF recordings can be used to detect ULF cerebrovascular buffering of BP in clinical populations where pharmacological or gravitational manipulations of BP may not be induced. From a mechanistic perspective, these data identify that sympathetic pathways responsible for cerebrovascular control are disrupted by injury to the spinal cord. From a technical perspective, our data indicate that PSI may be a statistically more powerful metric to detect differences in cerebrovascular buffering of BP between uninjured and SCI groups and can account for important direct influences of arterial CO2 tension.

The results indicate that impaired cerebrovascular buffering after SCI may be due to the loss of supraspinal sympathetic control over the cerebrovasculature, which results from the disruption of descending sympathetic pathways traversing the spinal cord (20, 36). This frequently occurs after cervical SCI as the sympathetic preganglionic neurons contributing to the superior cervical ganglia that are responsible for cerebrovascular tone [located primarily at the T1−T3 spinal segments (20, 36)] are disconnected from supraspinal sympathetic tonic support (20). The increase in phase synchrony in cervical SCI may contribute to the highly prevalent orthostatic intolerance in this population, as elevated phase synchrony is associated with fainting (16).

In this study, WDA clearly demonstrated impaired cerebrovascular buffering after SCI in the identical frequency range (0.02–0.03 Hz) to that shown by our group previously to be impaired by pharmacological blockade of sympathetic cerebrovascular control in uninjured individuals (30). The anatomic disruption of descending sympathoexcitatory pathways is similar to pharmacological α1-receptor antagonism such that in both situations effects of norepinephrine on the vasculature are largely inhibited. Cervical SCI results in blunted sympathetic preganglionic excitation, and therefore very little norepinephrine release occurs by ganglionic neurons innervating the vasculature. In contrast, α1-receptor antagonism leads to the reduced capacity for norepinephrine to influence downstream cascades within the smooth muscle responsible for altering vascular tone. With cervical SCI, there is additional disruption of sympathetic influences on β-receptors, which may additionally impact cerebrovascular regulation (8, 10). In both scenarios, any parasympathetic influence on cerebrovascular tone is intact and functional (37, 38). In short, our findings provide supporting evidence using known sympathetic neuroanatomic changes occurring after SCI to support previous pharmacological sympathetic α1-blockade data from our group, indicating that adrenergic pathways exert influences on the cerebrovasculature in the ULF range (30).

WDA detected a greater influence of arterial CO2 tension on CBF in participants with SCI, as indicated by the increased PSI between CO2 and CBF. Our group has previously examined the CBF responsiveness to induced hypercapnia and hypocapnia (47); however, the present data are the first to show that at rest in participants with SCI the relationship between arterial CO2 and CBF is altered. These relationships certainly deserve to be explored further, as alterations in cerebrovascular sensitivity to arterial CO2 tension are associated with a number of prevalent secondary health issues after SCI, such as cognitive dysfunction and sleep disordered breathing (1, 2, 27, 32–34, 44). Even after statistically accounting for the resting CO2 tension, the significant impairment of cerebrovascular buffering of BP in SCI persisted. As such, the utilization of WDA for cerebrovascular buffering is a robust research tool to evaluate the cerebrovascular buffering of BP while accounting for the influence of arterial CO2 tension.

This study corroborates work demonstrating a previously unknown frequency (0.02–0.03 Hz) in which the sympathetic nervous system appears to be modulating cerebrovascular tone (11–13, 30, 31). Although the systemic vasculature has been well established to have supraspinal sympathetic modulation occurring at a frequency of 0.07–0.2 Hz, there is now mounting evidence that the cerebrovasculature is modulated at VLF or ULF ranges (30, 31). The teleological rationale for the brain operating as a high-pass filter, where rapid changes in BP are relatively less buffered compared with slower changes may be to allow for increased perfusion during periods of mental activation, an organization that would theoretically not interfere with other more rapid cerebrovascular regulatory mechanisms such as neurovascular coupling (17, 27, 40).

Our analysis indicates that WDA holds greater statistical power to detect differences in cerebrovascular buffering of BP. Transfer function analysis parameters were not different in the ULF range between groups; however, we confirmed our previous findings that in the LF range, phase was reduced between BP and CBF (22), implying impaired cerebrovascular buffering in SCI. Our group’s work has demonstrated that the LF phase closely correlates with Windkessel compliance (42), indicating that viscoelastic properties of individuals with SCI may be compromised. This finding corroborates our preclinical and clinical work showing that SCI is associated with stiffening of central and cerebral arteries (18, 24, 25). The effect size for the ULF PSI was threefold greater than the LF transfer function phase between uninjured and SCI groups, suggesting that WDA may be a more statistically powerful approach for detecting impairments in cerebrovascular buffering of BP.

The present data support the contention that nonlinear and nonstationary approaches are able to detect differences in the ULF cerebrovascular buffering from supine resting hemodynamic data, which is complementary to that detected in standard frequency ranges using traditional linear approaches such as transfer function analysis. The concept that nonlinear and nonstationary relationships underlie hemodynamic interactions supports recent work showing that baroreflex regulation of the systemic vasculature exhibits nonlinear and dynamic behavior (14, 15).

The primary cardiovascular consequence after SCI is the loss of supraspinal tonic control of the vasculature, which is widely thought to operate in the LF range (roughly 10 s in humans), at least in the systemic vasculature, and certainly at the level of sympathetic neurons (29). We cannot be certain, as is the case in most study designs, that what we have measured reflects solely the loss of sympathetic control after SCI. However, our data, based off what we know about descending sympathetic pathways after SCI, combined with our previous work using pharmacological blockade (30), strongly suggests this is the case. Further to this, although difficult to conclusively show, our data suggest that sympathetic medially cerebrovascular buffering is occurring at a frequency previously unknown to be sympathetically mediated. Specifically, two studies, using either pharmacological [i.e., Prazosin in Saleem et al. (30)] or neuroanatomic [i.e., SCI) in the present study] interventions, have demonstrated that there appears to be a loss of regulation at a much different frequency (i.e., 0.025–0.03 Hz). This unique aspect of the present study remains to be conclusively demonstrated.

In the present study, WDA detected significant impairments in similar frequency ranges to those previously shown to be impacted by sympathetic vascular blockade (30). These changes persisted after correction for the direct influence that arterial blood gases exert on CBF. As WDA and transfer function analysis both detected changes without potentially dangerous perturbations in BP, these approaches both appear to be clinically relevant for detecting altered cerebrovascular buffering, although WDA was more statistically powerful. Future studies should explore strategies for preventing/rehabilitating cerebrovascular buffering of BP. Reducing the amount of disruption of descending sympathetic pathways due to SCI may be a viable target for restoring cerebrovascular function and health and mitigating the drastically elevated risk of stroke (4, 48), vascular-cognitive impairment (22, 26, 44), and orthostatic intolerance in this population.

GRANTS

This work was supported by funding to the laboratory of A. A. Phillips from the Libin Cardiovascular Institute of Alberta, Hotchkiss Brain Institute, Rick Hansen Institute, and Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research as well as an ICORD seed grant supported by the Blusson Integrated Cures Partnership (to P. N. Ainslie and A. A. Phillips). P. N. Ainslie and G. B. Coombs were supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council, and P. N. Ainslie is a Canada Research Chair.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.S., D.V., Z.S., A.H.X.L., O.F.B., G.B.C., T.M., Z.D., Y.-C.T., and A.A.P. conceived and designed research; S.S., A.H.X.L., G.B.C., T.M., and A.A.P. analyzed data; S.S., D.V., A.H.X.L., J.W.S., A.V.K., P.N.A., Y.-C.T., and A.A.P. interpreted results of experiments; S.S., J.W.S., and A.A.P. prepared figures; S.S., Z.S., J.W.S., A.V.K., P.N.A., Y.-C.T., and A.A.P. drafted manuscript; S.S., D.V., Z.S., A.H.X.L., J.W.S., O.F.B., G.B.C., T.M., A.V.K., P.N.A., Z.D., Y.-C.T., and A.A.P. edited and revised manuscript; S.S., D.V., Z.S., A.H.X.L., J.W.S., O.F.B., G.B.C., T.M., A.V.K., P.N.A., Z.D., Y.-C.T., and A.A.P. approved final version of manuscript; D.V., Z.S., O.F.B., T.M., A.V.K., Z.D., and A.A.P. performed experiments.

Footnotes

The most commonly used term to describe cerebrovascular buffering of BP has been “cerebral autoregulation.” However, as this term implies that the buffering function of the cerebrovasculature is an active and automated regulatory process, it does not incorporate the recent realization that a significant portion of this process is passively accomplished by the compliant nature of the brain vasculature. The term “cerebral pressure-flow relationships” has been used recently to incorporate both active and passive regulatory processes. We posit that the term “cerebrovascular buffering of BP” optimally incorporates the active and passive functions occurring and is specific enough to not overlap with the variety of pressure and flow interactions occurring in the brain that are not related to the buffering of BP.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ainslie PN, Duffin J. Integration of cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity and chemoreflex control of breathing: mechanisms of regulation, measurement, and interpretation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 296: R1473–R1495, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.91008.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chiodo AE, Sitrin RG, Bauman KA. Sleep disordered breathing in spinal cord injury: a systematic review. J Spinal Cord Med 39: 374–382, 2016. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2015.1126449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cragg JJ, Noonan VK, Dvorak M, Krassioukov A, Mancini GBJ, Borisoff JF. Spinal cord injury and type 2 diabetes: results from a population health survey. Neurology 81: 1864–1868, 2013. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000436074.98534.6e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cragg JJ, Noonan VK, Krassioukov A, Borisoff J. Cardiovascular disease and spinal cord injury: results from a national population health survey. Neurology 81: 723–728, 2013. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a1aa68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duschek S, Hadjamu M, Schandry R. Enhancement of cerebral blood flow and cognitive performance following pharmacological blood pressure elevation in chronic hypotension. Psychophysiology 44: 145–153, 2007. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2006.00472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eigenbrodt ML, Rose KM, Couper DJ, Arnett DK, Smith R, Jones D. Orthostatic hypotension as a risk factor for stroke: the atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study, 1987-1996. Stroke 31: 2307–2313, 2000. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.31.10.2307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamner JW, Tan CO, Lee K, Cohen MA, Taylor JA. Sympathetic control of the cerebral vasculature in humans. Stroke 41: 102–109, 2010. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.557132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ide K, Boushel R, Sørensen HM, Fernandes A, Cai Y, Pott F, Secher NH. Middle cerebral artery blood velocity during exercise with beta-1 adrenergic and unilateral stellate ganglion blockade in humans. Acta Physiol Scand 170: 33–38, 2000. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201x.2000.00757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meel-van den Abeelen ASS, Simpson DM, Wang LJY, Slump CH, Zhang R, Tarumi T, Rickards CA, Payne S, Mitsis GD, Kostoglou K, Marmarelis V, Shin D, Tzeng Y-C, Ainslie PN, Gommer E, Müller M, Dorado AC, Smielewski P, Yelicich B, Puppo C, Liu X, Czosnyka M, Wang C-Y, Novak V, Panerai RB, Claassen JAHR. Between-centre variability in transfer function analysis, a widely used method for linear quantification of the dynamic pressure-flow relation: the CARNet study. Med Eng Phys 36: 620–627, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Min J-H, Kwon H-M, Nam H. The effect of propranolol on cerebrovascular reactivity to visual stimulation in migraine. J Neurol Sci 305: 136–138, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2011.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Montano N, Cogliati C, da Silva VJ, Gnecchi-Ruscone T, Massimini M, Porta A, Malliani A. Effects of spinal section and of positive-feedback excitatory reflex on sympathetic and heart rate variability. Hypertension 36: 1029–1034, 2000. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.36.6.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montano N, Gnecchi-Ruscone T, Porta A, Lombardi F, Malliani A, Barman SM. Presence of vasomotor and respiratory rhythms in the discharge of single medullary neurons involved in the regulation of cardiovascular system. J Auton Nerv Syst 57: 116–122, 1996. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(95)00113-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moskalenko IE, Demchenko IT, Burov SV, Deriĭ IP. [Role of the sympathetic nervous system in regulating blood supply to the brain]. Fiziol Zh SSSR Im I M Sechenova 63: 1088–1095, 1977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moslehpour M, Kawada T, Sunagawa K, Sugimachi M, Mukkamala R. Nonlinear identification of the total baroreflex arc. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 309: R1479–R1489, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00278.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moslehpour M, Kawada T, Sunagawa K, Sugimachi M, Mukkamala R. Nonlinear identification of the total baroreflex arc: higher-order nonlinearity. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 311: R994–R1003, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00101.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ocon AJ, Kulesa J, Clarke D, Taneja I, Medow MS, Stewart JM. Increased phase synchronization and decreased cerebral autoregulation during fainting in the young. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 297: H2084–H2095, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00705.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phillips AA, Chan FH, Zheng MMZ, Krassioukov AV, Ainslie PN. Neurovascular coupling in humans: Physiology, methodological advances and clinical implications. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 36: 647–664, 2016. doi: 10.1177/0271678X15617954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phillips AA, Cote AT, Bredin SSD, Krassioukov AV, Warburton DER. Aortic stiffness increased in spinal cord injury when matched for physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc 44: 2065–2070, 2012. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182632585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phillips AA, Hansen A, Krassioukov AV. In with the new and out with the old: enter multivariate wavelet decomposition, exit transfer function. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 311: H735–H737, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00512.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phillips AA, Krassioukov AV. Contemporary cardiovascular concerns after spinal cord injury: mechanisms, maladaptations & management. J Neurotrauma 32: 1927–1942, 2015. doi: 10.1089/neu.2015.3903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Phillips AA, Krassioukov AV, Ainslie PN, Cote AT, Warburton DER. Increased central arterial stiffness explains baroreflex dysfunction in spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma 31: 1122–1128, 2014. doi: 10.1089/neu.2013.3280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phillips AA, Krassioukov AV, Ainslie PN, Warburton DER. Perturbed and spontaneous regional cerebral blood flow responses to changes in blood pressure after high-level spinal cord injury: the effect of midodrine. J Appl Physiol 116: 645–653, 2014. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01090.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Phillips AA, Krassioukov AV, Ainslie PN, Warburton DER. Baroreflex function after spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma 29: 2431–2445, 2012. doi: 10.1089/neu.2012.2507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Phillips AA, Matin N, Frias BB, Zheng MMZ, Jia M, West CR, Dorrance AM, Laher I, Krassioukov AV, Jia M, West CR, Dorrance AM, Laher I, Krassioukov AV. Rigid and remodelled: cerebrovascular structure and function after experimental high-thoracic spinal cord transection. J Physiol 15: 1177–1188, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Phillips AA, Matin N, Jia M, Squair JW, Monga A, Zheng MMZ, Sachdeva R, Yung A, Hocaloski S, Elliott S, Kozlowski P, Dorrance AM, Laher I, Ainslie PN, Krassioukov AV. Transient hypertension after spinal cord injury leads to cerebrovascular endothelial dysfunction and fibrosis. J Neurotrauma 35: 573–581, 2018. doi: 10.1089/neu.2017.5188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phillips AA, Squair JR, Currie KD, Tzeng Y-CC, Ainslie PN, Krassioukov AV. 2015 ParaPan American Games: Autonomic function, but not physical activity, is associated with vascular-cognitive impairment in spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma 34: 1283–1288, 2017. doi: 10.1089/neu.2016.4751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Phillips AA, Warburton DERR, Ainslie PN, Krassioukov AV. Regional neurovascular coupling and cognitive performance in those with low blood pressure secondary to high-level spinal cord injury: improved by alpha-1 agonist midodrine hydrochloride. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 34: 794–801, 2014. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pires PW, Dams Ramos CM, Matin N, Dorrance AM. The effects of hypertension on the cerebral circulation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 304: H1598–H1614, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00490.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ryan KL, Rickards CA, Hinojosa-Laborde C, Cooke WH, Convertino VA. Arterial pressure oscillations are not associated with muscle sympathetic nerve activity in individuals exposed to central hypovolaemia. J Physiol 589: 5311–5322, 2011. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.213074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saleem S, Teal PD, Kleijn WB, Ainslie PN, Tzeng Y-C. Identification of human sympathetic neurovascular control using multivariate wavelet decomposition analysis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 311: H837–H848, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00254.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saleem S, Tzeng Y-C, Kleijn WB, Teal PD. Detection of impaired sympathetic cerebrovascular control using functional biomarkers based on principal dynamic mode analysis. Front Physiol 7: 685, 2017. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sankari A, Martin JL, Bascom AT, Mitchell MN, Badr MS. Identification and treatment of sleep-disordered breathing in chronic spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 53: 145–149, 2015. doi: 10.1038/sc.2014.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Short DJ, Stradling JR, Williams SJ. Prevalence of sleep apnoea in patients over 40 years of age with spinal cord lesions. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 55: 1032–1036, 1992. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.55.11.1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silvestrini M, Pasqualetti P, Baruffaldi R, Bartolini M, Handouk Y, Matteis M, Moffa F, Provinciali L, Vernieri F. Cerebrovascular reactivity and cognitive decline in patients with Alzheimer disease. Stroke 37: 1010–1015, 2006. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000206439.62025.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Squair J, Phillips AA, Harmon M, Krassioukov DA. Emergency management of autonomic dysreflexia with neurological complications. Can Med Assoc J 188: 1100−1103, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strack AM, Sawyer WB, Marubio LM, Loewy AD. Spinal origin of sympathetic preganglionic neurons in the rat. Brain Res 455: 187–191, 1988. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90132-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Talman WT. Parasympathetic influences on cerebral circulation: a link to arterial baroreflexes. In: Neural Mechanisms of Cardiovascular Regulation. Boston, MA: Springer, 2004, p. 357–370. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-9054-9_16. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Talman WT, Dragon DN. Parasympathetic nerves influence cerebral blood flow during hypertension in rat. Brain Res 873: 145–148, 2000. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(00)02490-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tan CO, Hamner JW, Taylor JA. The role of myogenic mechanisms in human cerebrovascular regulation. J Physiol 591: 5095–5105, 2013. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.259747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tzeng Y-C, Ainslie PN. Blood pressure regulation IX: cerebral autoregulation under blood pressure challenges. Eur J Appl Physiol 114: 545–559, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s00421-013-2667-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tzeng YC, Ainslie PN, Cooke WH, Peebles KC, Willie CK, MacRae BA, Smirl JD, Horsman HM, Rickards CA. Assessment of cerebral autoregulation: the quandary of quantification. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 303: H658–H671, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00328.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tzeng YC, Chan GSH, Willie CK, Ainslie PN. Determinants of human cerebral pressure-flow velocity relationships: new insights from vascular modelling and Ca2+ channel blockade. J Physiol 589: 3263–3274, 2011. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.206953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wan D, Krassioukov AV. Life-threatening outcomes associated with autonomic dysreflexia: a clinical review. J Spinal Cord Med 37: 2–10, 2014. doi: 10.1179/2045772313Y.0000000098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wecht JM, Bauman WA. Decentralized cardiovascular autonomic control and cognitive deficits in persons with spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med 36: 74–81, 2013. doi: 10.1179/2045772312Y.0000000056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Willie CK, Macleod DB, Shaw AD, Smith KJ, Tzeng YC, Eves ND, Ikeda K, Graham J, Lewis NC, Day TA, Ainslie PN. Regional brain blood flow in man during acute changes in arterial blood gases. J Physiol 590: 3261–3275, 2012. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.228551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Willie CK, Tzeng Y-C, Fisher JA, Ainslie PN. Integrative regulation of human brain blood flow. J Physiol 592: 841–859, 2014. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.268953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilson LC, Cotter JD, Fan JL, Lucas RAI, Thomas KN, Ainslie PN. Cerebrovascular reactivity and dynamic autoregulation in tetraplegia. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 298: R1035–R1042, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00815.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu J-CC, Chen Y-CC, Liu L, Chen T-JJ, Huang W-CC, Cheng H, Tung-Ping S. Increased risk of stroke after spinal cord injury: a nationwide 4-year follow-up cohort study. Neurology 78: 1051–1057, 2012. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31824e8eaa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]