Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the leading cause of dementia in the elderly, characterized by neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), senile plaques (SPs), and a progressive loss of neuronal cells in selective brain regions. Rab10, a small Rab GTPase involved in vesicular trafficking, has recently been identified as a novel protein associated with AD. Interestingly, Rab10 is a key substrate of leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2), a serine/threonine protein kinase genetically associated with the second most common neurodegenerative disease Parkinson’s disease. However, the phosphorylation state of Rab10 has not yet been investigated in AD. Here, using a specific antibody recognizing LRRK2-mediated Rab10 phosphorylation at the amino acid residue threonine 73 (pRab10-T73), we performed immunocytochemical analysis of pRab10-T73 in hippocampal tissues of patients with AD. pRab10-T73 was prominent in NFTs in neurons within the hippocampus in all cases of AD examined, whereas immunoreactivity was very faint in control cases. Other characteristic AD pathological structures including granulovacuolar degeneration, dystrophic neurites and neuropil threads also contained pRab10-T73. The pRab10-T73 immunoreactivity was diminished greatly following dephosphorylation with alkaline phosphatase. pRab10-T73 was further found to be highly co-localized with hyperphosphorylated tau (pTau) in AD, and demonstrated similar pathological patterns as pTau in Down syndrome and progressive supranuclear palsy. Although pRab10-T73 immunoreactivity could be noted in dystrophic neurites surrounding SPs, SPs were largely negative for pRab10-T73. These findings indicate that Rab10 phosphorylation could be responsible for aberrations in the vesicle trafficking observed in AD leading to neurodegeneration.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, dystrophic neurites, granulovacuolar degeneration, neurofibrillary tangles, neuropil threads, phosphorylated Rab10, senile plaques

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the most prevalent form of dementia first reported by Dr. Alois Alzheimer, predominantly causes the loss and destruction of neurons in the cerebral cortex, basal forebrain, and hippocampus, leading to a progressive and sequential decline in cognitive, behavioral, and motor functions [1]. Although the causes for the neurodegeneration largely remain unknown, AD is uniquely characterized by two pathologic hallmarks: senile plaques (SPs) and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) [2]. SPs are spherical extracellular pathological lesions with a central core made up of amyloid-β (Aβ) peptide fibrils, and can be positively stained by silver, Congo red, or Thioflavin, while NFTs are intracellular aggregates composed of bundles of paired helical filaments with the major component being a hyperphosphorylated form of the microtubule-associated protein tau [2]. Other prominent pathological features of AD are dystrophic neurites (DNs), granulovacuolar degeneration (GVD), Hirano bodies, neuropil threads, and cerebrovascular amyloid [2].

Only less than 10% of AD cases are considered familial AD, associated with genetic mutations in amyloid β protein precursor (AβPP), presenilin 1 (PS1), or presenilin 2 (PS2) [3–5]. Interestingly, a recent study has identified a rare variant of the Rab10 gene in cognitively normal individuals over the age of 75 who carry at least one APOE ε4 allele, a known AD genetic risk factor [6], suggesting the Rab10 genetic variation may be protective against AD development.

Rab10 is a small monomeric Ras-related GTP-binding protein with a predicted molecular weight of approximately 23 kDa. Like other Rab family GTPases, through its interaction with effectors or binding proteins, Rab10 functions as a key regulator of diverse aspects of intracellular vesicle trafficking. For example, Rab10 is involved in transport between early endosomes and recycling endosomes [7], coordinates with myosin-Va to mediate the translocation of GLUT4 glucose transporter-enriched vesicles to the plasma membrane [8], and regulates the trafficking rate of TLR4, a toll-like receptor essential for the innate immune response following LPS stimulation, from Golgi to plasma membrane [9]. In neurons, Rab10 has been reported to recycle AMPARs from endosomal compartments to synapses [10], and regulates intracellular vesicular trafficking to mediate axonogenesis [11, 12] and dendrite arborization [13, 14]. Increased expression of Rab10 mRNA in the temporal cortex of AD brains has been reported [6]. In vitro studies have found that knockdown of Rab10 decreased Aβ production, whereas the overexpression of Rab10 increased Aβ production in cultured neuroblastoma cells [6].

Recent studies have revealed that amino acid residue threonine (T73) of Rab10 can be specifically phosphorylated by LRRK2, a protein kinase associated with Parkinson’s disease, a site located within the center of the Rab10 effector binding switch II motif, indicating a likely critical role of phosphorylation in regulating its function [15–18]. Here, using a well-characterized rabbit antibody pRab10-T73 that has been demonstrated to specifically recognize Rab10 T73 phospho-epitope without cross-reactivity to other Rab proteins in human tissues [16], we performed immunohistochemical analyses to investigate the localization and expression of pRab10 and its co-localization with AD neuropathological hallmarks in vulnerable neurons of postmortem brains from patients with AD.

METHODS

Tissue

Formalin fixed hippocampal tissues from histopathologically confirmed AD and aged-matched control subjects were obtained postmortem from the University Hospitals of Cleveland Case Medical Center with an approved IRB protocol. Fixed tissues were dehydrated through graded ethanol followed by xylene and embedded in paraffin. Microtome consecutive sections of 6μm thickness were prepared as described before [19]. Cases used are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Information of brain tissues used in this study

| Diagnosis | Age (y) | Gender | Tissue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 50 | Male | hippocampus |

| Control | 91 | Male | hippocampus |

| AD | 68 | Male | hippocampus |

| AD | 78 | Female | hippocampus |

| AD | 80 | Female | hippocampus |

| AD | 84 | Female | hippocampus |

| DS | 61 | Male | cortex |

| DS | 65 | Male | hippocampus |

| PSP | 76 | Male | brainstem |

| PSP | 83 | Male | brainstem |

AD, Alzheimer’s disease; DS, Down syndrome; PSP, progressive supranuclear palsy.

Immunocytochemistry

Immunocytochemistry was performed by the peroxidase anti-peroxidase protocol [19]. Taken briefly, paraffin embedded brain tissue sections were first deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated in graded ethanol and incubated in Tris Buffered Saline (TBS, 50 mM Tris · HCl and 150 mM NaCl, pH = 7.6) for 10 min before antigen retrieval in 1X antigen decloaker (Biocare). Sections were rinsed with distilled H2O, incubated in TBS for 10 min, and blocked with 10% normal goat serum (NGS) in TBS at room temperature (RT) for 30 min. Tissue sections were further incubated with primary antibodies in TBS containing 1% NGS overnight at 4°C, and immunostained by the peroxidase-antiperoxidase based method as we described [20]. To confirm the specificity of the the pRab10-T73 antibody to the phosphorylated epitope, one tissue section was incubated with alkaline phosphatase (10 U/ml in 0.1 M tris with 0.01 M PMSF at pH = 8.0) overnight at RT, and an adjacent section incubated in buffer only, prior to immunostaining. Primary antibodies used included rabbit monoclonal anti-Rab10 (Cell Signaling, Cat No.: 8127, 1 : 100), rabbit polyclonal anti-pRab10-Thr73 (a kind gift from Dr. Kenneth Christensen [16], 1 : 50), mouse monoclonal anti-Aβ (6E10, BioLegend, Cat No.: SIG-39320-200, 1 : 1000), mouse monoclonal anti-phosphorylated Tau Ser202/Thr205 (AT8, Invitrogen, Cat No.: MN1020, 1 : 1000), and mouse monoclonal anti-phosphorylated Tau Ser396/404 (PHF1, gift of Dr. Peter Davies, 1 : 1000).

Immunofluorescence

Double immunofluorescence staining was used to investigate the co-localization between pRab10-T73 and other AD neuropathological features. Taken briefly, paraffin embedded tissue sections were deparaffinized in xylene and re-hydrated in graded ethanol. Then, the rehydrated brain tissue sections were incubated in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) at RT for 10 min followed by antigen retrieval in 1X Immuno/DNA retriever with citrate (BioSB) under pressure using BioSB’s TintoRetriever pressure cooker. The sections were gradually rinsed with distilled H2O for five times and then blocked with 10% NGS in PBS for 45 min at RT. The sections were incubated with primary antibodies in PBS containing 1% NGS overnight at 4°C. After 3 quick washes with 1% NGS in PBS, the sections were incubated in 10% NGS for 10 min and washed with 1% NGS in PBS for 1 min. Then, the sections were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488 or 568 dye labeled second antibodies (Invitrogen, 1 : 300) for 2 h at RT in dark, washed 3 times with PBS, stained with DAPI, washed again with PBS for 3 times, and finally mounted with Fluoromount-G mounting medium (Southern Biotech).

Confocal microscopy

All fluorescence images were captured at RT with a Leica SP8 gSTED confocal microscopy equipped with a motorized super Z galvo stage, two PMTs, 3 Hyd SP GaAsP detectors for gated imaging, and the AOBS system lasers including a 405 nm, Argon (458, 476, 488, 496, 514 nm), a tunable white light (470 to 670 nm), and a 592 nm STED depletion laser. Series of confocal images with optical thickness of 300 nm were collected using the 100x oil objective. 3D confocal images were reconstructed using Imaris after background subtraction.

RESULTS

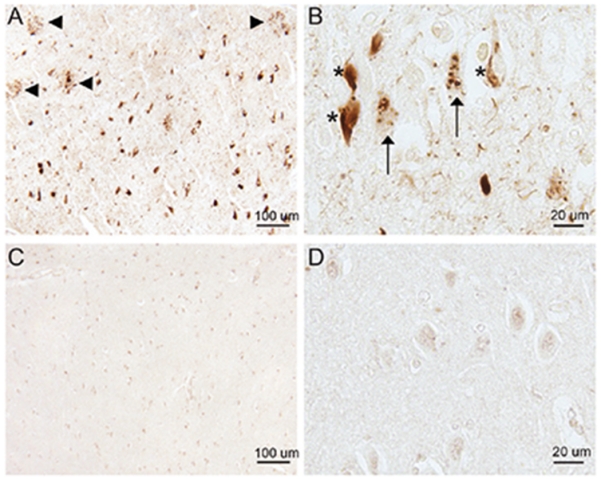

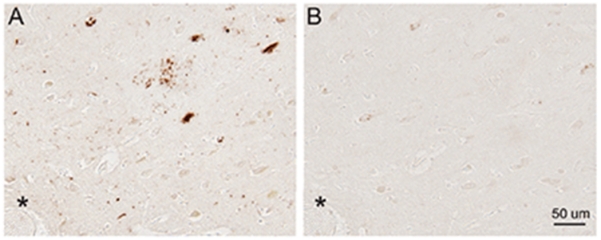

The antibody to total Rab10 did not recognize any neuropathological feature in hippocampal tissue sections from AD patients, and the Rab10 immunoreactivity in AD was comparable to that of age-matched control subjects (data not shown). However, the antibody to pRab10-T73 was remarkably immunoreactive with pathological lesions in AD hippocampus. Many pRab10-T73-positive NFTs and DNs around SPs were readily seen in all AD cases examined (Fig. 1A). At higher magnification, in addition to those flame shaped NFTs with well-defined borders, both GVD and neuropil threads were also found to contain pRab10-T73 (Fig. 1B). Of note, in hippocampus of normal control subjects, little pRab10-T73 was found in the CA1 neurons, with only some nuclei displaying weak immunoreactivity (Fig. 1C, D). The staining of pathology by the pRab10-T73 antibody in AD neurons was almost completely abolished by dephosphorylation of a serial adjacent tissue section with alkaline phosphatase (Fig. 2A, B).

Fig. 1.

Immunocytochemical analysis of pRab10-T73 in a hippocampal section from an AD patient and a normal subject. A) Lesions of NFTs and DNs around SPs (arrowheads) in the CA1 region of an 80-year-old AD patient contain pRab10-T73. B) Higher magnification of the CA1 region of a 67-year-old AD patient shows that in addition to NFTs (marked with asterisk), both GVD (arrows) and neuropil threads could be recognized by the antibody against pRab10-T73. C) In a normal control subject, CA1 neurons display weak pRab10-T73 immunoreactivity. D) Representative enlargements show faint immunoreactivity in some neuronal nuclei.

Fig. 2.

Immunoreactivity of pRab10-T73 is phosphatase sensitive. A) Immunocytochemistry of pRab10-T73 in an untreated section of hippocampus tissue from an 84-year-old AD patient. B) Immunocytochemistry of pRab10-T73 in a serial adjacent tissue section pre-treated with alkaline phosphatase. Landmark vessel is marked with asterisk.

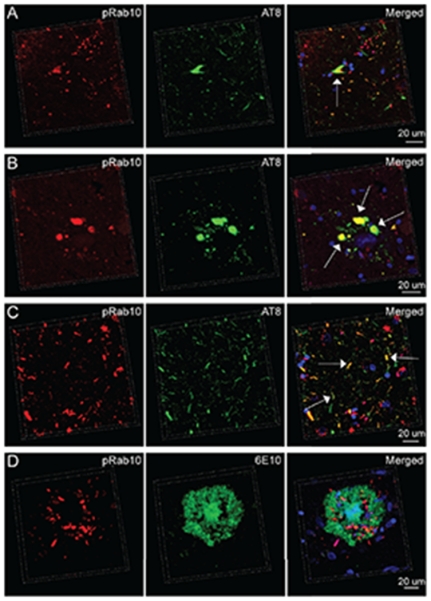

NFTs, DNs, GVD, and neuropil threads are all AD-associated neuropathological features composed of hyperphosphorylated tau [21]. We next performed double immunofluorescence staining of pRab10-T73 and hyperphosphorylated tau in AD hippocampus. AD neurons with AT8-postive NFTs were often positive for pRab10-T73 even though the staining pattern of pRab10-T73 did not completely co-localize with hyperphosphorylated tau within NFTs (Fig. 3A). Consistently, while many pRab10-T73-positive DNs and neuropil threads colocalized with hyperphosphorylated tau (Fig. 3A-C), some DNs and neuropil threads in AD hippocampus contained only hyperphosphorylated tau or only pRab10-T73 (Fig. 3A-C). Although the antibody to pRab10-T73 did not stain the amyloid component of SPs, many DNs around SPs displayed strong pRab10-T73 immunoreactivity (Fig. 1A). Double staining using the mouse monoclonal antibody 6E10 recognizing Aβ further demonstrates that the compact core of SPs was completely negative for pRab10-T73, while DNs surrounding SP cores contained pRab10 T73 (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

Double immunofluorescent staining of pRab10-T73 and phosphorylated tau (AT8) or Aβ (6E10) in a hippocampal section from an AD patient. A) Representative three-dimensional (3D) image showing the presence of pRab10-T73 in NFT-bearing AD pyramidal neurons (arrow). B) Representative 3D image showing pRab10-T73 in DNs containing phosphorylated tau (arrows). C) Representative 3D image showing pRab10-T73 in phosphorylated tau positive neuropil threads (arrows). D) Representative 3D image showing the minimal overlapping between pRab10 -T73 and SPs. The nuclei stained by DAPI are blue.

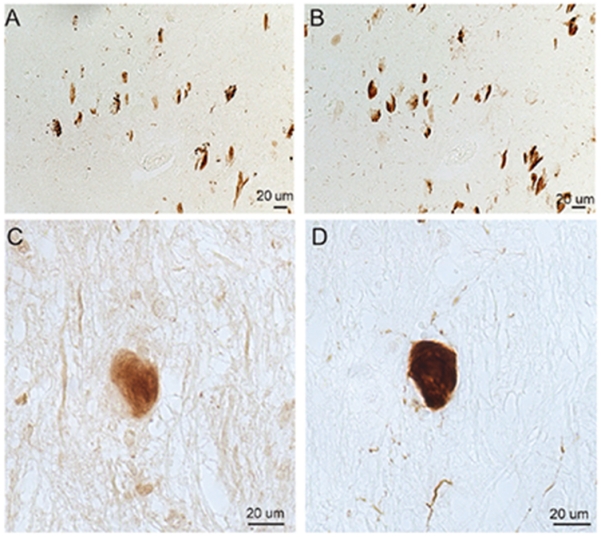

pRab10-T73 colocalized with pTau rather than Aβ aggregation indicating the likely close association between pRab10 and pTau pathology. To support this notion, we further investigated pRab10-T73 in Down syndrome (DS) and the tauopathy disease progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP). In adjacent sections of cortical tissues of cases of aged DS or the brainstem sections of PSP patients, we performed immunocytochemistry using the antibody to pRab10-T73 and antibodies to pTau, PHF1, or AT8. In cases of aged DS, many tau-positive NFT-bearing neurons also showed strong pRab10-T73 immunostaining (Fig. 4A, B). In the tauopathy disease PSP, many PSP tangles also showed increased pRab10-T73 immunostaining (Fig. 4C, D).

Fig. 4.

Immunocytochemical analysis of pRab10-T73 in a cortical section from a DS patient and the brainstem of a PSP patient. In serial sections of DS, many of the PHF1-positive NFTs (B) contain pRab10-T73 (A). In serial sections of PSP, a subset of AT8-positive PSP tangles (D) are pRab10-T73 positive (C).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, the present study provides the first immunocytochemical evidence identifying pRab10 as a novel component of AD pathological hallmark NFTs and other prominent pathological features such as DNs, GVD, and neuropil threads. The physiological role of pRab10 and its pathological significance in AD are still under investigation in our laboratories. Interestingly, aberrant vesicle trafficking especially defective synaptic vesicle trafficking has long been implicated in the pathogenesis of AD [22]. For example, as the early change correlating robustly with AD-associated cognitive deficits, synaptic loss in AD is primarily evidenced by reduced expression of proteins associated with synaptic vesicle docking, fusion and endocytosis [23–25]. Importantly, it has long been suggested that the metabolism of AβPP or production of Aβ is regulated by a variety of proteins involving vesicle trafficking from Golgi and endosome to the plasma membrane [26, 27]. And, NFTs were also thought to be either the cause or consequence of the impaired microtubule-dependent vesicle trafficking transport system [28]. Furthermore, GVD is intracellular aggregation of membrane-bound vacuoles, whereas DNs are characterized by the localized accumulation of vesicles [29]. Therefore, given the crucial role of Rab10 in vesicle trafficking, aberrant phosphorylation of Rab10 may be an important molecular mechanism underlying the altered vesicle trafficking observed in AD.

Rab10 is highly phosphorylated in AD without significantly changed expression of total Rab10 (data not shown), indicating the imbalance between protein kinases and phosphatases. Although the phosphatase regulating Rab10-dephosphorylation events has not yet been identified, recent studies have consistently reported and validated LRRK2-dependent phosphorylation of Rab10 at position Thr73 [15–18]. LRRK2 localizes to membranous vesicular structures or organelles such as endosomes, lysosomes, multivesicular bodies, and transport vesicles, the trafficking of which presumably involves Rab10 or other Rab-related proteins [30]. Thus, the identification of pRab10-T73 as a novel prominent feature of AD may present an activation of the LRRK2-Rab10 signaling pathway in AD. While another kinase similar to LRRK2 may also be responsible for the phosphorylation of Rab10, it is worth noting that the LRRK2 gene is located within a region on chromosome 12 linked to AD [31]. Indeed, the LRRK2 R1628P variant is associated with increased risk of AD in an Asian population [32]. Moreover, Parkinson’s disease-associated mutant LRRK2 has been recently shown to phosphorylate AβPP and regulate its toxicity [33]. These findings add further weight to the evidence implicating the likely pathological significance of LRRK2 or LRRK2-mediated Rab10 phosphorylation in AD. Further, a rare variant of the Rab10 gene has been shown to confer resilience for AD development in people over the age of 75 who carry at least one APOE ε4 allele. This, together with the reported increased expression of Rab10 mRNA in the temporal cortex of AD brains [6] and the in vitro studies showing overexpression of Rab10 increases Aβ production in cultured neuroblastoma cells [6], provide compelling evidence for an important role of Rab10 in AD.

While the staining patterns for pRab10-T73 and pTau colocalize, though not completely, with the pathological structures, it is unlikely that there is cross reaction of the pRab10 T73 antibody to Tau or pTau. pRab10 and pTau co-exist in many NFTs, DNs, and neuropil threads, and some pRab10-positive GVD structures are pTau-positive [34], indicating that pathologically occurring processes associated with some common kinases or phosphatases may be responsible for both Rab10 and tau hyperphosphorylation in AD. Along this line, tau can be phosphorylated by many kinases such as glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3), mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), extracellular receptor kinase (ERK), p38 MAPK and Jun-N-terminal kinase (JNK), and the increased expression and/or activation of these kinases have been reported in AD [35, 36]. Therefore, considering the concurrent accumulation of pRab10 and pTau in NFTs and some DNs or neuropil threads, it will be intriguing to investigate whether the activation of tau protein kinases is also present in pRab10-positive pathological structures, and explore the potential involvement of them in regulating Rab10 phosphorylation and related neuropathologies at different stages of the disease. Of course, on the basis of the facts that pRab10 and pTau do not completely co-localize with each other within NFTs, that there are a subset of pRab10-positive but pTau-negative or pRab10-positive but pTau-negative DNs, and that many pTau-positive neuropil threads are largely pRab10 negative, it remains possible that different or different combinations of a variety of kinases or phosphatases may be required for differentially determining the phosphorylation state of Rab10 and tau.

The pRab10-T73 antibody also recognized similar pathology as AD in patients with either DS or PSP, two other neurodegenerative diseases also characterized by the presence of prominent tauopathies, indicating pRab10 pathological events are closely associated with tauopathies. Of note, because Aβ has been implicated as the culprit of AD playing a pivotal role in the disease progression, it is not surprising that pRab10-positive DNs surrounding SPs usually demonstrated weak AβPP or Aβ immunoreactivity, although pRab10 immunoreactivity was not observed within SP compact cores. Like pRab10 and pTau, some forms of Aβ aggregates can also be found in some GVD bodies [37, 38]. And, according to a most recent study, the Rab10 kinase LRRK2 can phosphorylate AβPP [33]. Thus, pathological conditions associated with Rab10 phosphorylation may also be related to Aβ overproduction in AD. Through disturbed inter- and intracellular vesicle trafficking, pRab10 may alter the production, transportation, or even secretion of Aβ or tau. On the other hand, phosphorylated tau or the accumulation of Aβ or tau may also disrupt Rab10-mediated vesicle trafficking. Elucidating the molecular mechanism of aberrant Rab10 phosphorylation and its impact on the formation of SPs and NFTs may provide novel insights into our understanding of AD pathogenesis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the US National Institutes of Health (1R01NS089604 to X.W.) and the US Alzheimer’s Association (AARG-17-499682 to X.W.). We thank Dr. Kenneth Christensen for pRab10-T73 antibody, and Dr. Peter Davies for PHF1 antibody.

Footnotes

Authors’ disclosures available online (https://www.j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/18-0023).

REFERENCES

- [1].Alloul K, Sauriol L, Kennedy W, Laurier C, Tessier G, Novosel S, Contandriopoulos A. Alzheimer’s disease: A review of the disease, its epidemiology and economic impact. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 1998;27:189–221. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4943(98)00116-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Smith MA. Alzheimer disease. Int Rev Neurobiol. 1998;42:1–54. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7742(08)60607-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Czech C, Tremp G, Pradier L. Presenilins and Alzheimer’s disease: Biological functions and pathogenic mechanisms. Prog Neurobiol. 2000;60:363–384. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(99)00033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Fraser PE, Yang DS, Yu G, Levesque L, Nishimura M, Arawaka S, Serpell LC, Rogaeva E, St George-Hyslop P. Presenilin structure, function and role in Alzheimer disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1502:1–15. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(00)00028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Tanahashi H, Tabira T. Alzheimer’s disease-associated presenilin 2 interacts with DRAL, an LIM-domain protein. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:2281–2289. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.hmg.a018919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ridge PG, Karch CM, Hsu S, Arano I, Teerlink CC, Ebbert MTW, Murcia JDG, Farnham JM, Damato AR, Allen M, Wang X, Harari O, Fernandez VM, Guerreiro R, Bras J, Hardy J, Munger R, Norton M, Sassi C, Singleton A, Younkin SG, Dickson DW, Golde TE, Price ND, Ertekin-Taner N, Cruchaga C, Goate AM, Corcoran C, Tschanz J, Cannon-Albright LA, Kauwe JSK. Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Linkage, whole genome sequence, and biological data implicate variants in RAB10 in Alzheimer’s disease resilience. Genome Med. 2017;9:100. doi: 10.1186/s13073-017-0486-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Chen CCH, Schweinsberg PJ, Vashist S, Mareiniss DP, Lambie EJ, Grant BD. RAB-10 is required for endocytic recycling in the Caenorhabditis elegans intestine. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:1286–1297. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-08-0787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Chen Y, Wang Y, Zhang J, Deng Y, Jiang L, Song E, Wu XS, Hammer JA, Xu T, Lippincott-Schwartz J. Rab10 and myosin-Va mediate insulin-stimulated GLUT4 storage vesicle translocation in adipocytes. J Cell Biol. 2012;198:545–560. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201111091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Wang D, Lou J, Ouyang C, Chen W, Liu Y, Liu X, Cao X, Wang J, Lu L. Ras-related protein Rab10 facilitates TLR4 signaling by promoting replenishment of TLR4 onto the plasma membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:13806–13811. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009428107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Glodowski DR, Chen CCH, Schaefer H, Grant BD, Rongo C. RAB-10 regulates glutamate receptor recycling in a cholesterol-dependent endocytosis pathway. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:4387–4396. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-05-0486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Wang T, Liu Y, Xu XH, Deng CY, Wu KY, Zhu J, Fu XQ, He M, Luo ZG. Lgl1 activation of rab10 promotes axonal membrane trafficking underlying neuronal polarization. Dev Cell. 2011;21:431–444. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Schuck S, Gerl MJ, Ang A, Manninen A, Keller P, Mellman I, Simons K. Rab10 is involved in basolateral transport in polarized madin-darby canine kidney cells. Traffic. 2007;8:47–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Taylor CA, Yan J, Howell AS, Dong XT, Shen K. RAB-10 regulates dendritic branching by balancing dendritic transport. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005695. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Zou W, Yadav S, DeVault L, Jan YN, Sherwood DR. RAB-10-dependent membrane transport is required for dendrite arborization. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005484. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Fan Y, Howden AJ, Sarhan AR, Lis P, Ito G, Martinez TN, Brockmann K, Gasser T, Alessi DR, Sammler EM. Interrogating Parkinson’s disease LRRK2 kinase pathway activity by assessing Rab10 phosphorylation in human neutrophils. Biochem J. 2018;475:23–44. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20170803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Thirstrup K, Dachsel JC, Oppermann FS, Williamson DS, Smith GP, Fog K, Christensen KV. Selective LRRK2 kinase inhibition reduces phosphorylation of endogenous Rab10 and Rab12 in human peripheral mononuclear blood cells. Sci Rep. 2017;7:10300. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10501-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Steger M, Tonelli F, Ito G, Davies P, Trost M, Vetter M, Wachter S, Lorentzen E, Duddy G, Wilson S, Baptista MA, Fiske BK, Fell MJ, Morrow JA, Reith AD, Alessi DR, Mann M. Phosphoproteomics reveals that Parkinson’s disease kinase LRRK2 regulates a subset of Rab GTPases. Elife. 2016;5:e12813. doi: 10.7554/eLife.12813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ito G, Katsemonova K, Tonelli F, Lis P, Baptista MA, Shpiro N, Duddy G, Wilson S, Ho PW, Ho SL, Reith AD, Alessi DR. Phos-tag analysis of Rab10 phosphorylation by LRRK2: A powerful assay for assessing kinase function and inhibitors. Biochem J. 2016;473:2671–2685. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20160557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Zhu XW, Rottkamp CA, Boux H, Takeda A, Perry G, Smith MA. Activation of p38 kinase links tau phosphorylation, oxidative stress, and cell cycle-related events in Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2000;59:880–888. doi: 10.1093/jnen/59.10.880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Nunomura A, Perry G, Pappolla MA, Wade R, Hirai K, Chiba S, Smith MA. RNA oxidation is a prominent feature of vulnerable neurons in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 1999;19:1959–1964. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-06-01959.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Serrano-Pozo A, Frosch MP, Masliah E, Hyman BT. Neuropathological alterations in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2011;1:a006189. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Yao PJ. Synaptic frailty and clathrin-mediated synaptic vesicle trafficking in Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:24–29. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2003.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Coleman P, Federoff H, Kurlan R. A focus on the synapse for neuroprotection in Alzheimer disease and other dementias. Neurology. 2004;63:1155–1162. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000140626.48118.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Terry RD, Masliah E, Salmon DP, Butters N, DeTeresa R, Hill R, Hansen LA, Katzman R. Physical basis of cognitive alterations in Alzheimer’s disease: Synapse loss is the major correlate of cognitive impairment. Ann Neurol. 1991;30:572–580. doi: 10.1002/ana.410300410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].DeKosky ST, Scheff SW. Synapse loss in frontal cortex biopsies in Alzheimer’s disease: Correlation with cognitive severity. Ann Neurol. 1990;27:457–464. doi: 10.1002/ana.410270502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Gunawardena S, Goldstein LSB. Disruption of axonal transport and neuronal viability by amyloid precursor protein mutations in Drosophila. Neuron. 2001;32:389–401. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00496-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Small SA, Gandy S. Sorting through the cell biology of Alzheimer’s disease: Intracellular pathways to pathogenesis. Neuron. 2006;52:15–31. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Stamer K, Vogel R, Thies E, Mandelkow E, Mandelkow EM. Tau blocks traffic of organelles, neurofilaments, and APP vesicles in neurons and enhances oxidative stress. J Cell Biol. 2002;156:1051–1063. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200108057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Funk KE, Mrak RE, Kuret J. Granulovacuolar degeneration (GVD) bodies of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) resemble late-stage autophagic organelles. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2011;37:295–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2010.01135.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Biskup S, Moore DJ, Celsi F, Higashi S, West AB, Andrabi SA, Kurkinen K, Yu SW, Savitt JM, Waldvogel HJ, Faull RL, Emson PC, Torp R, Ottersen OP, Dawson TM, Dawson VL. Localization of LRRK2 to membranous and vesicular structures in mammalian brain. Ann Neurol. 2006;60:557–569. doi: 10.1002/ana.21019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].PericakVance MA, Bass MP, Yamaoka LH, Gaskell PC, Scott WK, Terwedow HA, Menold MM, Conneally PM, Small GW, Vance JM, Saunders AM, Roses AD, Haines JL. Complete genomic screen in late-onset familial Alzheimer disease - Evidence for a new locus on chromosome 12. JAMA. 1997;278:1237–1241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Zhao Y, Ho P, Yih Y, Chen C, Lee WL, Tan EK. LRRK2 variant associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32:1990–1993. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Chen ZC, Zhang W, Chua LL, Chai C, Li R, Lin L, Cao Z, Angeles DC, Stanton LW, Peng JH, Zhou ZD, Lim KL, Zeng L, Tan EK. Phosphorylation of amyloid precursor protein by mutant LRRK2 promotes AICD activity and neurotoxicity in Parkinson’s disease. Sci Signal. 2017;10:eaam6790. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aam6790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Dickson DW, Ksiezakreding H, Davies P, Yen SH. A monoclonal-antibody that recognizes a phosphorylated epitope in Alzheimer neurofibrillary tangles, neurofilaments and tau proteins immunostains granulovacuolar degeneration. Acta Neuropathol. 1987;73:254–258. doi: 10.1007/BF00686619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Martin L, Latypova X, Wilson CM, Magnaudeix A, Perrin ML, Yardin C, Terro F. Tau protein kinases: Involvement in Alzheimer’s disease. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12:289–309. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Dolan PJ, Johnson GVW. The role of tau kinases in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2010;13:595–603. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Dickson DW, Ksiezak-Reding H, Davies P, Yen SH. A monoclonal antibody that recognizes a phosphorylated epitope in Alzheimer neurofibrillary tangles, neurofilaments and tau proteins immunostains granulovacuolar degeneration. Acta Neuropathol. 1987;73:254–258. doi: 10.1007/BF00686619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Kumar S, Wirths O, Stuber K, Wunderlich P, Koch P, Theil S, Rezaei-Ghaleh N, Zweckstetter M, Bayer TA, Brustle O, Thal DR, Walter J. Phosphorylation of the amyloid beta-peptide at Ser26 stabilizes oligomeric assembly and increases neurotoxicity. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131:525–537. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1546-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]