Abstract

This paper reports on a cluster randomized trial of Cooperative Learning (CL) as a way to prevent escalation in alcohol use during middle school (N = 1,460 7th grade students, age 12–13, 7 intervention and 8 control schools). We hypothesized that CL, by bringing students together in group-based learning activities using positive interdependence, would interrupt the process of deviant peer clustering, provide at-risk youth with prosocial influences and, in turn, reduce escalations in alcohol use. Results indicated that CL significantly reduced growth in deviant peer affiliation and actual alcohol use, and effects for willingness to use alcohol were at the threshold of significance (p = .05). CL also attenuated the link between willingness to use alcohol and later alcohol use.

Although alcohol use starts among only a small percentage of youth during early adolescence, both the percentage of users and the amount of use continue to climb as youth get older (Johnston et al., 2010). This escalation in use has both immediate and long-term implications for health and well-being; for example, adolescent alcohol use is a key risk factor for disease, premature death, educational problems, diminished work capacity, and later substance abuse and dependence (Marshall, 2014; Van Ryzin & Dishion, 2014; WHO, 2014). Adolescent alcohol use can also interfere with brain development, including abnormalities in brain volume, white matter quality, and cognitive performance, including memory, attention, and executive function (Squeglia, Jacobus, & Tapert, 2009).

Current School-based Approaches to Alcohol Use Prevention

Many different approaches to prevention have arisen in response to the problem of escalating adolescent alcohol use. A common approach among school-based programs is to ask teachers or school counselors to deliver psychosocial content aimed at changing attitudes, normative beliefs, and/or resistance skills related to use of alcohol and other drugs (Greenberg et al., 2003). Although research has found these programs to be effective, meta-analyses have found small effects (i.e., mean ES = .05 in Wilson et al., 2001; median ES =.13 in Tobler et al., 2000). Some programs have relied on peer opinion leaders to deliver programs or augment program delivery, but these programs can have also had small effects (median ES = .17 in Tobler et al., 2000), and there is no consensus on best methods for identifying, recruiting, and retaining peer leaders (Valente & Pumpuang, 2007). In addition, some research has found that using peer opinion leaders in small groups can have “iatrogenic” effects, where programs create an increase in alcohol and other drug use in situations where social interactions are unsupervised (Dodge, Lansford, & Dishion, 2006; Dishion & Dodge, 2005). Moreover, research on these programs generally does not consider their impact on academic achievement. Since these programs require the expenditure of instructional time on activities that may not directly contribute to academic achievement, schools and districts may not be strongly compelled to adapt them, reducing their overall impact on public health.

A New Approach to Prevention

We propose a new approach to alcohol use prevention that relies on theory and research surrounding the etiology of adolescent alcohol use and the role of peers. During adolescence, peers become increasingly influential relative to parents (Steinberg & Monahan, 2007). Youth who are rejected by more prosocial peers due to lack of social skills and/or maladaptive social behavior tend to affiliate with one another (i.e., deviant peer clustering; Dishion et al., 1991), and within these deviant groups, delinquent behavior is modeled, facilitated, and reinforced (Dishion & Patterson, 2006). Research finds that escalation in alcohol use in adolescence has been linked to the influence of such peers who espouse or enact more delinquent behavior (Fergusson, Swain-Campbell, & Horwood, 2002; Van Ryzin et al., 2012). If the process of deviant peer clustering could be interrupted, and at-risk youth could be provided with the opportunity to cultivate friendships with low-risk (rather than exclusively deviant) youth, then these friendships could potentially confer a degree of protection (Ennett et al., 2006) by providing a context in which prosocial (rather than antisocial) behavioral norms are transmitted (Gest et al., 2011).

Our approach to prevention attempts to increase students’ social contacts and reduce social alienation through collaborative, group-based learning activities in school, which put at-risk youth in contact with low-risk, prosocial youth; theoretically, this should also interrupt the formation of deviant peer clusters. Our approach can be seen as an attempt to enhance the school social network by adding links representing new relationships among students. In some prevention contexts, such a change to the social network might be aimed at improving the spread of important ideas or practices (Valente, 2012). In our case, the goal is to improve the social climate of the school by essentially giving students the opportunity to make new friends outside of their existing social groups.

In order for group-based learning activities to promote social integration, however, they must establish a social context that reduces biases and prejudices among students who belong to different social groups (Pettigrew, 1998; Pettigrew & Tropp, 2008). A key ingredient of such a social context is “positive interdependence”, i.e., when goals are structured such that individuals can attain their goals if (and only if) others in their group also reach their goals (Deutsch, 1949, 1962). Under positive interdependence, patterns of peer interaction change. Instead of competing with or ignoring one another, peers are more likely to promote the success of one another through mutual assistance, emotional support, and sharing of resources. These positive social interactions, in turn, increase interpersonal attraction and acceptance, reduce peer rejection, support the development of new friendships, and, in an educational context, promote academic motivation and achievement (Johnson, Johnson, Roseth, & Shin, 2014; Roseth, Johnson & Johnson, 2008; Mikami et al., 2005). In fact, research on peer interactions reviewed by Bierman (2004) suggests that gains in social skills alone are insufficient to reduce peer rejection; rather, only positive interdependence (and the subsequent positive social interactions that arise from it) can motivate youth to re-evaluate previous conclusions regarding the social desirability of others.

Cooperative Learning (CL) is one of the few empirically supported instructional approaches that ensures the establishment of positive interdependence. CL is an umbrella term that includes reciprocal teaching, peer tutoring, and other group-based activities in which peers work together to maximize each other’s learning (Johnson, Johnson & Holubec, 2013). By structuring positive interdependence between students, CL contrasts with competitive and individualistic learning activities in which students compete against each other or work by themselves. CL has robust empirical evidence documenting its positive effects on interpersonal attraction, social acceptance, and academic achievement (Ginsburg-Block et al., 2006; Johnson & Johnson, 1989, 2005). In a recent meta-analysis, Roseth et al. (2008) demonstrated that CL was associated with greater achievement (ES = .46 to .65) and more positive peer relationships (ES = .42 to .56) as compared to competitive or individualistic instructional approaches. These findings suggest that CL can promote substantial increases in academic achievement while simultaneously addressing the social processes that can promote deviant peer clustering and escalations in alcohol use. Thus, CL presents a strong contrast to the approaches reviewed above, which require the sacrifice of instructional time for non-academic curricula. In addition, given that deviant peer clustering has been tied to a host of negative outcomes, including externalizing behavior, crime, risky sexual behavior, and depression (Fergusson, Swain-Campbell, & Horwood, 2002; Fergusson, Wanner, Vitaro, Horwood, & Swain-Campbell, 2003; Van Ryzin & Dishion, 2013; Van Ryzin, Johnson, Leve, & Kim, 2011), addressing these maladaptive social processes in schools could potentially have broad, wide-ranging positive effects.

Current Study

This paper reports on a small-scale cluster randomized trial of the Johnsons’ approach to Cooperative Learning (CL; Johnson et al., 2013) as an intervention to prevent escalation in adolescent alcohol use during middle school. We targeted middle schools because early adolescents have been found to be particularly vulnerable to peer influence (Kelly et al., 2012), and alcohol use at this age can provide an entry point into a deviant peer context where use is encouraged, increasing the risk of later clinical dependence (Van Ryzin & Dishion, 2014). Thus, early adolescence can be considered a critical period in the etiology of problematic alcohol use.

Other school-based prevention programs exist that incorporate the notion of positive interdependence. One well-known example is the Good Behavior Game (GBG), in which elementary school children work in small groups and earn rewards by inhibiting impulses, regulating emotions, and monitoring the behavior of classmates. Evidence indicates that the GBG is efficacious in reducing behavioral problems among elementary school populations (Leflot, van Lier, Onghena, & Colpin, 2013; Van Lier, Muthén, van der Sar, & Crijnen, 2004). However, unlike CL, the GBG has very little evidence of efficacy when used at the middle and high school levels. Therefore, for our purposes, CL was preferred.

We hypothesized that CL would interrupt the formation of deviant peer clusters by helping at-risk youth to develop positive relationships with low-risk, prosocial youth; in turn, reduced deviant peer influence should result in reduced alcohol use during the school year. Given the expectation that alcohol use in middle school would be low, we also evaluated CL effects on students’ self-reported willingness to use alcohol. Further, we evaluated whether CL would attenuate the link between self-reported willingness to use alcohol and later alcohol use.

Method

All aspects of this study were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the Oregon Research Institute. This study was registered as trial NCT03119415 in ClinicalTrials.gov under Section 801 of the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act.

Sample

The sample was derived from a small-scale randomized trial of CL in 15 rural middle schools in the Pacific Northwest. Schools were matched based upon demographics (i.e., size, free/reduced lunch percentage) and randomized to condition (i.e., intervention vs. waitlist control). We were concerned about the likelihood of losing schools assigned as controls, so we randomized an extra school to this condition (i.e., 8 waitlist control vs. 7 intervention schools).

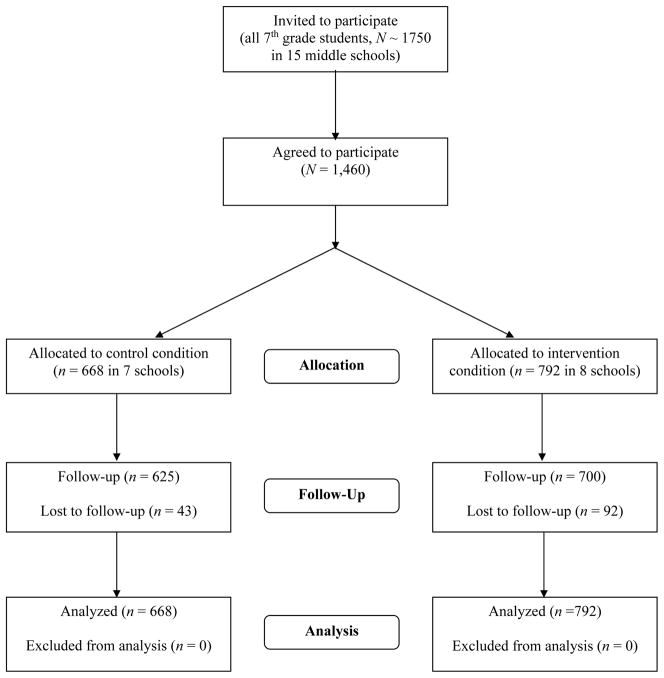

Our analytic sample included N = 1,460 7th grade students who enrolled in the project in the fall of 2016 (see Figure 1). We achieved greater than 80% student participation at each school by using a passive consent procedure and providing research staff to oversee the data collection. We also offered compensation to the schools for participating in the project, and enrolled participating students in a prize raffle. Student demographics by school are reported in Table 1. Overall, the sample was 48.2% female (N = 703) and 76.4% White (N = 1,116). Other racial/ethnic groups included Hispanic/Latino (14.3%, N = 209), multi-racial (4.2%, N = 61), and American Indian/Alaska Native (3.5%, N = 51); our sample included less than 1% Asian, African-American, and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander. Overall, 13.9% (N = 203) were reported as having Special Ed status, 79.6% (N = 1162) did not have Special Ed status, and 6.5% (N = 95) were missing this designation. Free and reduced price lunch (FRPL) status was not made available by the schools, although school-level FRPL figures (obtained from state records) are reported in Table 1.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram.

Table 1.

Descriptive data by school

| School | Intervention | N | % female | % White | % Special Ed | % FRPLa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yes | 211 | 48.8 | 74.4 | 13.3 | 53 |

| 2 | Yes | 47 | 55.3 | 78.7 | 12.8 | 66 |

| 3 | Yes | 94 | 39.4 | 62.8 | n/a | 62 |

| 4 | No | 80 | 50.0 | 92.5 | 26.3 | 65 |

| 5 | Yes | 89 | 47.2 | 85.4 | 18.0 | 72 |

| 6 | Yes | 93 | 46.2 | 90.3 | 18.3 | 71 |

| 7 | No | 44 | 45.5 | 93.2 | 18.2 | 33 |

| 8 | Yes | 70 | 51.4 | 80.0 | 12.9 | 57 |

| 9 | No | 63 | 42.6 | 84.1 | 19.0 | 45 |

| 10 | Yes | 64 | 31.3 | 71.9 | 4.7 | 95 |

| 11 | No | 144 | 47.2 | 66.7 | 16.7 | 61 |

| 12 | No | 170 | 54.1 | 48.8 | 11.8 | 84 |

| 13 | No | 158 | 50.6 | 89.9 | 11.4 | 66 |

| 14 | No | 43 | 48.8 | 88.4 | 16.3 | 39 |

| 15 | No | 90 | 53.3 | 82.2 | 15.6 | 46 |

State records.

Note. One school did not provide Special Ed status.

Procedure

Training for intervention school staff began in the fall of 2016 and continued throughout the 2016–2017 school year, consisting of 3 half-day in-person sessions, periodic check-ins via videoconference, and access to resources (e.g., newsletters). Training sessions were conducted by D. W. and R. T. Johnson, supported by the authors, and utilized Cooperation in the Classroom, 9th Edition by Johnson, Johnson, and Holubec (2013); each staff member was given a copy of the book. The three in-person training sessions per school were conducted in (1) late September and early October, (2) late October through early December, and (3) late January through late March. Due to the geographic dispersal of the schools, each school received training individually according to their own schedule for professional development.

Under the Johnson’s approach, CL can include reciprocal teaching, peer tutoring, collaborative reading, and other methods in which peers help each other learn in small groups under conditions of positive interdependence. The Johnsons’ approach also emphasizes individual accountability, explicit coaching in collaborative skills, a high degree of face-to-face interaction, and guided processing of group performance. CL is viewed as a conceptual framework within which teachers can apply the principal of positive interdependence to design their own group-based activities using existing curricula.

Measures

Student data collection was conducted in September/October 2016 (baseline) and March 2017 (follow-up) using on-line surveys (Qualtrics). The time between data collection points varied across schools but averaged five and a half months. To assess fidelity of implementation, we also conducted teacher observations. A Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained for these data from NIAAA (#CC-AA-17-011).

Alcohol use

Students reported on their use of alcohol in the last month using the following scale: No use = 1, Occasionally (1–3 times) = 2, Fairly often (4–6 times) = 3, Regularly (7–9 times) = 4, and All the time (10+ times) = 5. At baseline, 93.4% of students (N = 1,392) reported no alcohol use, but at follow-up that declined to 82.8% (N = 1,234).

Willingness to use alcohol

Students reported on their willingness to use alcohol in the company of friends (i.e., “Suppose you were with a group of friends and there was some alcohol that you could have if you wanted. How willing would you be to have one drink?”). Students responded using the following scale: Not at all willing = 1, A little willing = 2, Pretty willing = 3, and Very willing = 4. At baseline, 83.8% of students (N = 1,249) were not at all willing to try alcohol, but at follow-up that declined to 71.2% (N = 1,062).

Deviant peer affiliation

Students reported on the frequency in the last month with which they associated with other youth who engaged in delinquent activities, including “get in trouble a lot”, “fight a lot”, “take things that don’t belong to them”, and “skip school” (4 items overall). Alpha reliability was .76 at baseline and .79 at follow-up. Previous research has found this measure to be strongly predictive of later alcohol and other drug use (Van Ryzin et al., 2012).

Demographics

Youth sex, ethnicity, and Special Ed status were obtained from school records. Ethnicity was dichotomized to White (0) vs. non-White (1); the latter included Hispanic/Latino students. Sex was coded as Male (0) and Female (1), and Special Ed status was coded as No (0) and Yes (1).

Observed intervention fidelity

Research staff blind to intervention assignment observed teaching practices in intervention and control schools. We trained our observers to adequate reliability using simulated data before they were permitted to conduct observations in actual classrooms, and we used an established observation protocol for key aspects of CL (e.g., positive interdependence; Veenman et al., 2002). Observations were conducted once in the late fall/early winter and again in the spring. Observers remained in a classroom for an entire class period. In smaller schools, observers were generally able to observe all 7th grade teachers within a single day; for large schools, observers randomly selected a subset of all 7th grade teachers.

Analysis Plan

The multilevel nature of our data (i.e., students within schools) required an analytical approach that addressed statistical dependencies created by nesting. Thus, we evaluated our hypotheses with nested random coefficients analysis, which allocates variance either “within” or “between” groups, accounting for dependencies (Fitzmaurice et al., 2004). In this model, student data (e.g., alcohol use, deviant peer affiliation) were at Level 1 (“within”) and school data (i.e., intervention condition) were at Level 2 (“between”). All three outcomes (i.e., willingness to use alcohol, deviant peer affiliation, and actual alcohol use) were included in a single model. All predictors were uncentered.

All modeling was conducted using Mplus 7.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 2012). Since our outcome variables demonstrated a degree of skew, all models were fit using Robust Maximum Likelihood (RML), which provides so-called “sandwich” or Huber-White standard errors. RML can provide unbiased estimates in the presence of missing and/or non-normal data. Standard measures of fit are reported, including the chi-square (χ2), comparative fit index (CFI), non-normed or Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and root-mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA). CFI/TLI values greater than .95, RMSEA values less than 0.5, and a non-significant χ2 (or a ratio of χ2/df < 3.0) indicate good fit (Bentler, 1990; Bentler & Bonett, 1980; Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Results

Descriptive data for all variables and correlations are presented in Table 2. ANOVA models indicated that students in intervention and control schools did not differ in terms of baseline levels of deviant peer affiliation [F(1,1354) = 3.43, ns] or alcohol use [F(1,1354) = 1.54, ns]. The two sets of schools were different, however, in terms of willingness to use alcohol at baseline [F(1,1358) = 7.27, p < .01], with intervention schools being slightly lower; this effect was small (R2 = .01). With regards to the fidelity observations, ANOVA indicated significantly higher levels of observed positive interdependence in intervention schools as compared to control schools, F(1,98) = 10.79, p < .01, R2 = .10.

Table 2.

Correlations and descriptive data

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Willingness (baseline) | — | ||||||||

| 2. Willingness (follow-up) | .47*** | — | |||||||

| 3. Deviant peers (baseline) | .41*** | .33*** | — | ||||||

| 4. Deviant peers (follow-up) | .28*** | .45*** | .42*** | — | |||||

| 5. Alcohol use (baseline) | .47*** | .30*** | .29*** | .24*** | — | ||||

| 6. Alcohol use (follow-up) | .37*** | .60*** | .28*** | .42*** | .49*** | — | |||

| 7. Special Ed status | −.01 | −.03 | .07** | .01 | .00 | −.01 | — | ||

| 8. Ethnicity | −.05* | −.06* | −.04 | −.07** | −.02 | −.03 | .04 | — | |

| 9. Sex | .04 | .03 | −.09** | −.03 | −.04 | −.01 | −.09** | −.04 | — |

|

| |||||||||

| N | 1456 | 1324 | 1453 | 1323 | 1453 | 1325 | 1365 | 1460 | 1460 |

| M | 1.20 | 1.32 | 1.44 | 1.49 | 1.07 | 1.15 | .15 | .76 | .48 |

| SD | .55 | .69 | .62 | .67 | .41 | .59 | - | - | - |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

We first evaluated intervention effects on willingness to use alcohol, deviant peer affiliation, and actual alcohol use at follow-up, controlling for baseline measures and student demographics. Model fit was good, CFI = .96, TLI = .92, RMSEA = .03, χ2(21) = 45.22, p < .01, χ2/df = 2.15. Results are reported in Table 3. CL resulted in significantly lower rates of growth in deviant peer affiliation and actual alcohol use, and the effect on willingness to use alcohol was at the threshold of significance (p = .05; β = -.69). The large standardized regression coefficients associated with the intervention condition suggest that CL explained most of the between-school variance in these outcomes. Student demographics were not predictive of any outcome except for ethnic differences in willingness to use alcohol; non-Whites were somewhat less willing to use alcohol at follow-up as compared to Whites (β = −.05).

Table 3.

Intervention effects at follow-up

| Willingness to Use Alcohol (follow-up) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Predictor | B (SE) | β | Sig |

| Level 1 | |||

| Willingness (baseline) | .47 (.05) | .38 | p < .001 |

| Special Ed | −.04 (.06) | −.02 | ns |

| Ethnicity | −.08 (.04) | −.05 | p < .05 |

| Sex | .03 (.03) | .02 | ns |

| Level 2 | |||

| Intervention condition | −.10 (.05) | −.69 | p = .05 |

|

| |||

| Deviant Peer Affiliation (follow-up) | |||

|

| |||

| Predictor | B (SE) | β | Sig |

|

| |||

| Level 1 | |||

| Deviant peer affiliation (baseline) | .38 (.05) | .37 | p < .001 |

| Special Ed | −.03 (.06) | −.02 | ns |

| Ethnicity | −.06 (.04) | −.04 | ns |

| Sex | .00 (.05) | .00 | ns |

| Level 2 | |||

| Intervention condition | −.12 (.05) | −.68 | p < .01 |

|

| |||

| Alcohol Use (follow-up) | |||

|

| |||

| Predictor | B (SE) | β | Sig |

|

| |||

| Level 1 | |||

| Alcohol use (baseline) | .57 (.07) | .43 | p < .001 |

| Special Ed | −.02 (.03) | −.02 | ns |

| Ethnicity | −.02 (.03) | −.01 | ns |

| Sex | .01 (.02) | .01 | ns |

| Level 2 | |||

| Intervention condition | −.09 (.04) | −.61 | p < .05 |

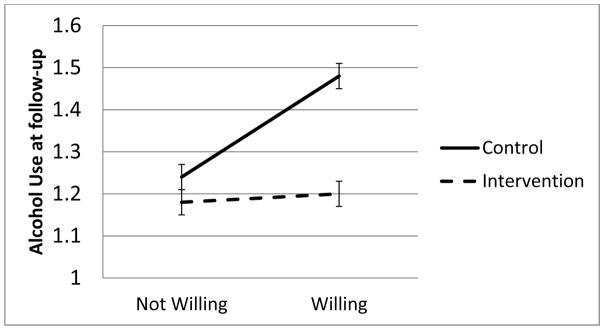

Our second and third models evaluated the ability of the intervention to attenuate the link between willingness to use alcohol (at baseline) and actual alcohol use (at follow-up). First, we ran a model predicting alcohol use at follow-up that included willingness to use alcohol at baseline. This model fit the data well, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.00, RMSEA = .00, χ2(9) = 5.69, ns. The results indicate that (1) willingness to use alcohol at baseline significantly predicted alcohol use at follow-up, and (2) the intervention predicted a significant reduction in alcohol use even when controlling for alcohol use willingness at baseline (see Table 4). Then, to test moderation, we inserted the (cross-level) interaction between the intervention condition and willingness to use alcohol at baseline. In the resulting model, this interaction effect was significant, B = −.21, SE = .10, p < .05 (Mplus did not provide standardized coefficients or model fit indices). The interaction effect is graphed in Figure 2 using two groups: not at all willing (1) and a little willing (2). The figure suggests that there were no significant differences in alcohol use at follow-up between the two willingness conditions for those students in the intervention schools, whereas the two willingness conditions show significant differences in alcohol use at follow-up among students in the control schools.

Table 4.

Predicting alcohol use, controlling for willingness to use alcohol

| Alcohol Use (follow-up) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Predictor | B (SE) | β | Sig |

| Level 1 | |||

| Alcohol use (baseline) | .56 (.07) | .40 | p < .001 |

| Special Ed | −.03 (.03) | −.02 | ns |

| Ethnicity | −.01 (.04) | −.01 | ns |

| Sex | .00 (.03) | .00 | ns |

| Willingness (baseline) | .19 (.06) | .18 | p < .01 |

| Level 2 | |||

| Intervention condition | −.09 (.04) | −.63 | p < .05 |

Figure 2.

Interaction effect.

Discussion

Although Cooperative Learning (CL) possesses robust empirical evidence supporting its ability to encourage academic engagement and achievement, as well as interpersonal attraction and social acceptance (Ginsburg-Block et al., 2006; Roseth et al., 2008), it has not yet been tested as a prevention program aimed at deviant peer clustering and adolescent alcohol use. In this study, we found that CL was able to significantly reduce self-reported deviant peer affiliation in intervention schools as compared to control schools, suggesting that group-based activities in classrooms were giving at-risk youth some degree of access to a broader cross-section of the student social network. We also found that CL reduced growth in actual alcohol use from baseline to follow-up, and attenuated longitudinal links between willingness to use alcohol at baseline and actual alcohol use at follow-up. The intervention’s ability to significantly reduce willingness to use alcohol was not conclusively demonstrated (β = −.69; p = .05), but our results were strongly suggestive; given the size of the beta coefficient, we propose that lack of power due to the small number of schools in our sample was a key factor that limited our ability to detect statistical significance.

Overall, our results suggest that access to more positive, prosocial influences may have reduced the strength of deviant peer influences among youth who were at risk for early escalations in alcohol use. We hasten to add that this conclusion regarding the mechanism by which CL exerted its effects is based solely upon theory, and these processes merit additional exploration in future research.

This research is limited in three key ways. First, it is based upon a relatively homogeneous sample of rural students that was about three-quarters White, which limits the generalizability of the results. Future research should include more diverse urban populations. Second, all measures were self-report, which limits internal validity. Future research should consider additional data sources, such as teachers and/or parents. And third, the small number of schools in our sample (i.e., 15) and the small number of time points (i.e., 2) limited the complexity of the models that we were able to fit to the data; thus, we were unable to explore effects on other substances simultaneously (e.g., tobacco and marijuana) or explore more complex mediating processes. As more data are gathered during the coming school year, we will be able to empirically test the hypothesis that effects on substance use and related problem behavior are mediated by deviant peer affiliation, for example, or social network structure.

Conclusion

In sum, these findings hold a great deal of promise. Although much remains to be discovered, the initial results confirm our hypotheses regarding the ability of CL to reduce deviant peer clustering and alcohol use, and to attenuate the influence of alcohol use willingness on actual use. Future research should explore effects on related delinquent behavior (e.g., aggression, bullying), as well as emotional and mental health.

From an applied perspective, CL has demonstrated its ability to enhance academic achievement and promote positive peer relationships simultaneously in previous research; thus, it can be seen as a low-risk, high-reward approach to alcohol use prevention that should enhance, rather than detract from, academic outcomes. This gives CL a significant advantage over many existing prevention approaches. At the same time, the implementation of CL can be seen as a form of professional development for teachers, rather than an off-the-shelf program to be implemented for a year or two and then discarded. Once implemented, CL techniques can be shared among staff members, and new teachers can be taught by existing staff. Furthermore, CL can be used in any subject across the school day to the degree that suits the individual teacher, and is adaptable to any existing curriculum. Thus, our hope is that the results reported here can contribute to increased interest in CL as a permanent, sustainable component of teacher training and educational practice at the elementary, middle, and high school level that can support positive academic, social, and behavioral outcomes simultaneously.

Acknowledgments

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R34AA024275-01) provided financial support for this project. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIAAA or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM, Bonett DG. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin. 1980;88:588–606. [Google Scholar]

- Bierman KL. Peer rejection: Developmental processes and intervention strategies. Guilford Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch M. A theory of cooperation and competition. Human Relations. 1949;2:129–151. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch M. Cooperation and trust: Some theoretical notes. In: Jones M, editor. Nebraska symposium on motivation. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press; 1962. pp. 275–319. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Dodge KA. Peer contagion in interventions for children and adolescents: Moving towards an understanding of the ecology and dynamics of change. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:395–400. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-3579-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Patterson GR. The development and ecology of antisocial behavior in children and adolescents. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental psychopathology: Vol. 3. Risk, disorder, and adaptation. New York: Wiley; 2006. pp. 503–541. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Patterson GR, Stoolmiller M, Skinner ML. Family, school, and behavioral antecedents to early adolescent involvement with antisocial peers. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27:172–180. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge K, Lansford JE, Dishion TJ. The problem of deviant peer influences in intervention programs. In: Dodge KA, Dishion TJ, Lansford JE, editors. Deviant peer influences in programs for youth. New York: Guilford; 2006. pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ennett ST, Bauman KE, Hussong A, Faris R, Foshee VA, et al. The peer context of adolescent substance use: Findings from social network analysis. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2006;16:159–186. [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Swain-Campbell NR, Horwood LJ. Deviant peer affiliations, crime and substance use: A fixed effects regression analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:419–430. doi: 10.1023/a:1015774125952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Wanner B, Vitaro F, Horwood LJ, Swain-Campbell N. Deviant peer affiliations and depression: confounding or causation? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31:605–618. doi: 10.1023/a:1026258106540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzmaurice GM, Laird NM, Ware JH. Applied longitudinal analysis. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gest SD, Osgood DW, Feinberg ME, Bierman KL, Moody J. Strengthening prevention program theories and evaluations: Contributions from social network analysis. Prevention Science. 2011;12:349–360. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0229-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg-Block MD, Rohrbeck CA, Fantuzzo JW. A meta-analytic review of social, self-concept, and behavioral outcomes of peer-assisted learning. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2006;98:732–749. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg MT, Weissberg RP, O’Brien MU, Zins JE, Fredericks L, Resnik H, Elias MJ. Enhancing school-based prevention and youth development through coordinated social, emotional, and academic learning. American Psychologist. 2003;58:466–474. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.6-7.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DW, Johnson R. Cooperation and competition: Theory and research. Edina, MN: Interaction Book Company; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DW, Johnson R. New developments in social interdependence theory. Psychology Monographs. 2005;131:285–358. doi: 10.3200/MONO.131.4.285-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DW, Johnson R, Holubec E. Cooperation in the classroom. 9. Edina, MN: Interaction Book Company; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DW, Johnson RT, Roseth CJ, Shin TS. The relationship between motivation and achievement in interdependent situations. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2014;44:622–633. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2009. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2010. NIH Publication No. 10–7583. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly AB, Chan GCK, Toumbourou JW, O’Flaherty M, Homel R, Patton GC, Williams J. Very young adolescents and alcohol: Evidence of a unique susceptibility to peer alcohol use. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37:414–419. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leflot G, van Lier PA, Onghena P, Colpin H. The role of children’s on-task behavior in the prevention of aggressive behavior development and peer rejection: A randomized controlled study of the Good Behavior Game in Belgian elementary classrooms. Journal of School Psychology. 2013;51:187–199. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall EJ. Adolescent alcohol use: risks and consequences. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2014;49:160–164. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agt180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikami AY, Boucher MA, Humphreys K. Prevention of peer rejection through a classroom-level intervention in middle school. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2005;26:5–23. doi: 10.1007/s10935-004-0988-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. MPlus: Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables User’s Guide. 7. Los Angeles, CA: StatModel; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew TF. Intergroup contact theory. Annual Review of Psychology. 1998;49:65–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew TF, Tropp LR. How does intergroup contact reduce prejudice? Meta-analytic tests of three mediators. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2008;38(6):922–934. [Google Scholar]

- Roseth CJ, Johnson DW, Johnson RT. Promoting early adolescents’ achievement and peer relationships: The effects of cooperative, competitive, and individualistic goal structures. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;134:223–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squeglia LM, Jacobus J, Tapert SF. The influence of substance use on adolescent brain development. Clinical EEG and Neuroscience. 2009;40:31–38. doi: 10.1177/155005940904000110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Monahan KC. Age differences in resistance to peer influence. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:1531–1543. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobler NS, Roona MR, Ochshorn P, Marshall DG, Streke AV, Stackpole KM. School-based adolescent drug prevention programs: 1998 meta-analysis. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2000;20:275–336. [Google Scholar]

- Valente TW. Network interventions. Science. 2012;337:49–53. doi: 10.1126/science.1217330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente TW, Pumpuang P. Identifying opinion leaders to promote behavior change. Health Education & Behavior. 2007;34:881–896. doi: 10.1177/1090198106297855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Lier PA, Muthén BO, van der Sar RM, Crijnen AA. Preventing disruptive behavior in elementary schoolchildren: impact of a universal classroom-based intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:467–478. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ryzin MJ, Dishion TJ. From antisocial behavior to violence: A model for the amplifying role of coercive joining in adolescent friendships. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2013;54:661–669. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ryzin MJ, Dishion TJ. Adolescent deviant peer clustering as an amplifying mechanism underlying the progression from early substance use to late adolescent dependence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2014;55:1153–1161. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ryzin MJ, Fosco GM, Dishion TJ. Family and peer predictors of substance use from early adolescence to early adulthood: An 11-year prospective analysis. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37:1314–1324. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ryzin MJ, Johnson AB, Leve LD, Kim HK. The number of sexual partners and health-risking sexual behavior: Prediction from high school entry to high school exit. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2011;40:939–949. doi: 10.1007/s10508-010-9649-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veenman S, van Benthum N, Bootsma D, van Dieren J, van der Kemp N. Cooperative learning and teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education. 2002;18:87–103. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DB, Gottfredson DC, Najaka SS. School-based prevention of problem behaviors: A meta-analysis. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 2001;17:247–272. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global status report on alcohol and health 2014. World Health Organization; 2014. [Google Scholar]