Abstract

C-reactive protein (CRP) is an acute-phase protein synthesized by hepatocytes in response to pro-inflammatory cytokines during inflammatory/infectious processes. CRP exists in conformationally distinct forms such as the native pentameric CRP and monomeric CRP (mCRP) and may bind to distinct receptors and lipid rafts and exhibit different functional properties. It is known as a biomarker of acute inflammation, but many large-scale prospective studies demonstrate that CRP is also known to be associated with chronic inflammation. This review is focused on discussing the clinical significance of CRP in chronic inflammatory and neurodegenerative diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, age-related macular degeneration, hemorrhagic stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease, including recent advances on the implication of CRP and its forms specifically on the pathogenesis of these diseases. Overall, we highlight the advances in these areas that may be translated into promising measures for the diagnosis and treatment of inflammatory diseases.

Keywords: C-reactive protein, chronic inflammation, biomarker, cardiovascular disease, diabetes

Introduction

C-reactive protein (CRP) belongs to the family of pentraxins and exists in at least two conformationally distinct forms—such as the native pentameric CRP (pCRP) and monomeric CRP (mCRP). Studies suggest that pCRP possesses both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory properties in a context-dependent manner (1). By contrast, mCRP exerts potent pro-inflammatory actions on endothelial cells, endothelial progenitor cells, leukocytes, and platelets and may amplify the inflammatory response (1). The dissociation of pCRP into pro-inflammatory mCRP might directly link CRP to inflammation. CRP is considered as a serum biomarker in patients undergoing acute inflammatory response (2–4). The elevation in baseline CRP level was shown to be useful to gauge chronic inflammation and tissue damage resulting from excessive inflammation or failure of the initial inflammatory response (5). Higher CRP concentrations may be indicative of an acute infection or inflammation and therefore are often excluded in studies of chronic inflammation. Higher CRP concentration over time, rather than spikes in CRP, may result in cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) and problems leading to atherosclerosis (6). Furthermore, some chronic inflammatory diseases such as hemorrhagic stroke, Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and Parkinson’s disease (PD) are also associated with CRP formation (7–10) (Table 1). In this review, we emphasize recent advances that may explain how conformational changes in CRP are linked to chronic inflammation and neurodegeneration.

Table 1.

Chronic inflammatory diseases associated with CRP levels.

| Disease category | Pathology/disease type | CRP (mCRP/nCRP) levels | Role and clinical significance of CRP |

|---|---|---|---|

| CVD | Atherosclerosis, chronic heart failure | Elevated mCRP levels (11) | Inflammatory biomarker, risk predictor, participant |

| T2DM | Insulin resistance | Elevated CRP levels (12) | Inflammatory biomarker, risk predictor, mediator |

| AMD | Progressive visual impairment, senile macular degeneration, blinding disease | Elevated CRP levels (13) | Inflammatory biomarker, risk predictor |

| Hemorrhagic Stroke | Intracerebral hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage, brain injury | Elevated CRP levels (14) | Inflammatory biomarker, risk predictor |

| AD | Neurodegenerative disorder, dementia | Reduced/elevated CRP levels (15) | Inflammatory biomarker, no causal role |

| PD | Neurodegenerative disorder, motor symptoms | Elevated CRP levels (16) | Inflammatory biomarker, risk predictor |

CRP plays an important role in the progression of various chronic inflammatory diseases. This table lists diseases associated with nCRP and monomeric CRP (mCRP) levels. Although any potential mechanism underlying the effect of CRP on these processes is incompletely elucidated, its clinical significance appears to be positive.

CVD, cardiovascular disease; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; PD, Parkinson’s disease; AMD, age-related macular degeneration; CRP, C-reactive protein; nCRP, native CRP.

CRP and CVDs

Elevated levels of numerous inflammatory biomarkers have been implicated to predict adverse cardiovascular events. Several studies indicate the predictive CRP values in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS). The routine biomarkers of CVD include troponin I (cTnI) and creatine kinase isoenzyme (CK-MB) that are mainly synthesized in cardiac muscle cells. Both cTnI and CK-MB may be detected in the blood during severe ischemia, degeneration, and necrosis of cardiomyocytes; but lack the sensitivity to detect minute damage to cardiomyocytes (17, 18). CRP is the biomarker that most strongly correlates with future cardiovascular events and may be slightly elevated during the early stage of myocardial vascular inflammation (7, 19). Unlike other markers of inflammation, CRP levels are stable over long periods and display no diurnal variation. In addition, these may be inexpensively measured with available high-sensitivity assays and have shown specificity in terms of the prediction of CVD risk (20). At present, high-sensitivity CRP (hs-CRP) is gaining popularity under clinical settings, as it allows the detection of lower levels of CRP. A moderate increase in hs-CRP is thought to predict an increased risk of coronary events in unstable angina pectoris patients and its detection is a reliable predictor of the risk of CVDs (21–23). During the course of atherosclerotic plaque formation, the stimulation of the local inflammatory response may lead to elevated levels of hs-CRP, which has been identified as a risk factor for atherosclerosis (24). These findings have highlighted the significant importance of hs-CRP for the evaluation of atherosclerotic inflammation. However, a recent meta-analysis called into question the clinical value of CRP as a predictor of CVD risk. In their prospective study, Danesh et al. (25) revealed CRP as a relatively modest predictor of CVD. Many studies have identified elevated serum CRP levels in response to cardiovascular events and that CRP levels may strongly and independently predict adverse cardiovascular events, including myocardial infarction (MI), ischemic stroke, and sudden cardiac death (26).

Although CRP is an inflammatory biomarker, its involvement in the pathogenesis of CVD is questionable. CRP has been demonstrated to exhibit prothrombotic property, and high concentrations of CRP may activate the coagulation system, resulting in an increase in the level of prothrombin and D-dimer (27, 28). In a clinical study with a long follow-up, the investigators reported high predictive values of CRP in atherosclerotic thrombotic events after the implantation of drug-eluting stents (29). Studies investigating the relationship between stent thrombosis, hs-CRP levels, and statin therapy revealed that statins may only reduce the formation of early stent thrombosis in patients with high levels of hs-CRP. Rosuvastatin was similarly shown to markedly reduce the incidence of CVD and CVD-associated mortality and decrease levels of CRP and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) (30). Furthermore, Eisenhardt et al. (31) found a localized dissociation mechanism of pCRP into mCRP mediated by activated platelets, thereby resulting in the deposition of mCRP in atherosclerotic plaques. A clinical trial has demonstrated the effectiveness of statins in reducing the incidence of future cardiovascular events is associated with decreased pCRP level (32). Ruptured plaques and inflamed tissues in patients with ACS were shown to be more prone to opsonization by mCRP, leading to the consumption of autoantibodies against mCRP (33). In addition, multiple epidemiological studies have revealed the participation of CRP in the pathogenesis of CVDs based on genetic polymorphisms that affect CRP levels (34). However, some epidemiological studies failed to support the notion that the common variation in CRP gene had an alternative effect on the occurrence of coronary heart diseases. A Mendelian randomization study of over 28,000 cases and 100,000 controls found that a lack of concordance between the effect of the CRP genotypes on the risk of coronary heart diseases and CRP levels argued against a causal association of CRP with coronary heart disease (28). Using genetic variants as the unconfounded proxies of CRP concentration, Mendelian randomization meta-analysis of individual participant data from 47 epidemiological studies showed that CRP concentration itself was unlikely to be the modest causal factor in coronary heart disease (35). Steady state CRP levels in serum are influenced by CRP gene haplotypes. Although elevated CRP level has lately been found to be a consistent and relatively strong risk factor for CVD, no association was observed between CRP gene haplotypes and coronary heart disease (36). A prospective, nested case-control study design from the Physicians’ Health Study cohort demonstrated that none of the single nucleotide polymorphisms related to higher CRP levels showed any association with the risk of incident MI or ischemic stroke (37). Therefore, these epidemiological data indicate a significant interaction between both genetic and environmental factors and increased CRP levels that predict a greater risk of CVD events.

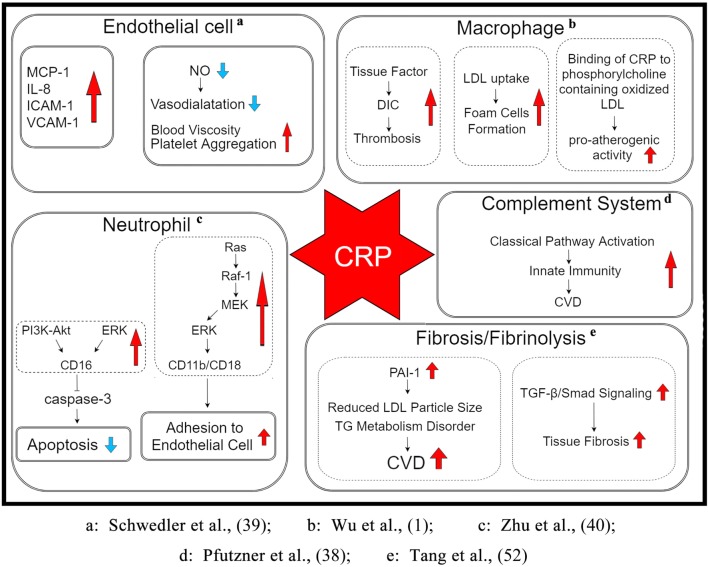

Some basic research shows that the inflammatory response plays a central role in various phases of atherosclerosis, i.e., from the initial recruitment of circulating leukocytes to the arterial wall to the rupture of unstable plaques, thereby resulting in the clinical manifestations of the disease. CRP may be critically involved in each of these stages by directly influencing processes, including complement activation, apoptosis, endothelial nitric oxide (NO) synthase inhibition, vascular cell activation, monocyte recruitment, lipid accumulation and thrombosis, and pro-inflammatory cytokine formation (38). Taken together, CRP appears to play a pivotal role in many aspects of CVD, as described below (Figure 1):

mCRP induces endothelial cells to produce monocyte chemoattractant protein 1, interleukin-8 (IL-8), intercellular adhesion molecule 1, and vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (39).

mCRP inhibits the apoptosis of neutrophils that is partly meditated by the activation of the low-affinity immunoglobulin G immune complex receptor FcγRIII (CD16) via stimulation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-ERK (MEK) signaling pathways, leading to the inhibition of caspase-3. This process is partly mediated by the activation of neutrophil ERK via the Ras/Raf-1/MEK cascade that increases CD11b/CD18 expression, thereby promoting adhesion to endothelial cells (40).

C-reactive protein activates macrophages to secrete tissue factor, a powerful procoagulant, which may lead to disseminated intravascular coagulation and thrombosis during inflammatory states.

C-reactive protein increases the uptake of LDL into macrophages and enhances the ability of macrophages to form foam cells. It binds to phosphocholine of oxidized LDL.

Through the above action, CRP induces the classical complement pathway and directly activates and amplifies the innate immunity, a process that has already been associated with the initiation and progression of CVD.

C-reactive protein inhibits endothelial NO synthase expression. NO, an important signaling molecule, is closely associated with the regulation of vasodilatation, blood rheology, platelet aggregation, and other physiological as well as pathological processes.

C-reactive protein upregulates plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) expression and activity. PAI-1 reduces LDL particle size in conjunction with triglyceride metabolism disorder, leading to an increased risk of CVD (41).

C-reactive protein mediates tissue fibrosis in CVD by activating transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)/Smad signaling via TGF-β1-dependent and -independent mechanisms.

Figure 1.

The potential mechanism underlying the role of CRP in the pathogenesis of CVDs. CRP may be involved in various stages through its direct influence on pathophysiological processes such as the activation of endothelial cells and macrophages, inhibition of apoptosis of neutrophils and expression of endothelial NO synthase, stimulation of the complement cascade, enhancement of PAI-1 activity and LDL uptake, accumulation of lipid and thrombosis, and upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokine expression. Abbreviations: DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; CVD, cardiovascular diseases; TG, triglyceride; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1; ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule 1; VCAM-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1; NO, nitric oxide; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; PAI-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β; CRP, C-reactive protein.

CRP and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM)

Type 2 diabetes mellitus is a serious disease associated with high morbidity and mortality. CRP, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and IL-6 may be triggered by the excessive adipose tissue to activate insulin signaling pathways, resulting in insulin resistance that eventually progresses into T2DM (42). Cross-sectional and prospective studies have demonstrated a relationship between elevated CRP levels and increased risk for T2DM (43). Higher levels of hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c, %), the indicator of overall glycemic control in diabetics, were positively correlated with elevated CRP levels even after adjustment, as seen in elderly patients with T2DM (44, 45). In comparison to subjects with normal fasting glucose, patients with diabetes and impaired fasting glucose level (defined by the reduction in glucose from 110 to 100 mg/dL and/or elevated plasma glucose level at 2 h in the oral glucose tolerance test) showed a strong increase in hs-CRP (46, 47). Furthermore, clinical studies showed elevated serum concentrations of fetuin-A, vascular endothelial growth factor, and CRP in T2DM patients with diabetic retinopathy (DR), suggestive of the increased risk of DR with high CRP level (48).

Based on the multitude of clinical observations, CRP appears to be not only a marker of chronic inflammation but also a mediator of kidney diseases in basic research. CRP is known to bind to its receptor FcγRII (CD32/CD64) and directly activate or interact with a number of signaling pathways in the process of inflammation, fibrosis, and aging. CRP may activate the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling under diabetic conditions (49). To date, the most consistent animal data in CRP research were obtained with the diabetic mouse model of CRP; CRP was shown to clearly enhance renal fibrosis in diabetic nephropathy (T2DN) via CD32b-Smad3-mTOR signaling (50). In addition, CRP could activate Smad3 via both TGF-β-dependent and ERK/MAPK crosstalk mechanisms, leading to the direct binding of Smad3 to p27. The suppression of Smad3 or FcγRII CD32 may result in the inhibition of CRP-induced p27-dependent G1 cell cycle arrest and promotion of CDK2/cyclin E-dependent G1/S transition of tubular epithelial cells (51). Moreover, CRP could markedly mediate tissue fibrosis in several cardiovascular and kidney diseases by activating the TGF-β/Smad3 pathway (52).

CRP and Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD)

Age-related macular degeneration, an acquired disease of the macula, is characterized by progressive visual impairment, owing to the late-onset neurodegeneration of the photoreceptor-retinal pigment epithelial complex (53–57). Chronic inflammation is thought to be critically involved in the pathophysiology of AMD. A cross-sectional study documented an obviously higher CRP level in the exudative form of AMD (eAMD) as compared to that observed in the early form (56). Higher CRP levels were closely associated with the higher risk of exudative AMD (55, 58–60). In comparison with pCRP, pro-inflammatory mCRP strongly influenced endothelial cell phenotypes, indicative of its potential role in choroidal vascular dysfunction in AMD (61). A recent observational study of elderly European patients by Cipriani et al. (62) suggested no causal association between CRP concentrations and AMD. However, complement activation may be involved in the development of AMD. It was found that mCRP played a role in choroidal vascular dysfunction in AMD by influencing endothelial cell phenotypes in vitro and ex vivo (63). In addition, high levels of CRP could activate the complement system at the retina/choroid interface and contribute to chronic inflammation and subsequent tissue damage (64). These clinical results indicate that CRP plays an important role in the pathogenesis of AMD and may be used to assess the severity of AMD. Plasma levels of CRP are independently associated with the risk of AMD, but whether CRP is causally associated with AMD or acts as a mere marker of AMD is uncertain.

CRP and Hemorrhagic Stroke

During the initial stages of hemorrhagic stroke, including intracerebral hemorrhage and subarachnoid hemorrhage, the reflex mechanisms are activated to protect cerebral perfusion. The inflammatory process and hyperglycemia are involved in the spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage (sICH) as well as the progression of sICH-induced brain injury (65, 66). Several prospective studies have reported the association between higher CRP levels and increased disability risk of ischemic stroke (67). CRP elevation displays negative prognostic implications for many conditions, while elevations in CRP as a consequence of the major acute-phase response following ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke are associated with death and vascular complications (68). In a cross-sectional study, an increase in hs-CRP level was observed in patients with ischemic infarction but not in those with hemorrhagic stroke, suggestive of the role of hs-CRP in the initial diagnosis of the stroke type (69). Moreover, CRP was an independent predictor of mortality and its expression was significantly correlated with poor clinical outcomes in sICH (70–72). Although several studies have shown the higher level of CRP in patients with ischemic stroke, its potential role in various stroke types, particularly in ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, needs to be investigated.

CRP and AD

Alzheimer’s disease is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by gradually progressive cognitive decline and functional impairment. Neuroinflammation may play a potential role in AD pathogenesis (73, 74). However, the precise mechanism related to AD phenotype remains unclear. CRP was clearly recognized in the senile plaques (SP) from patients with AD using immunostaining, implying that the process of SP formation may include an acute-phase inflammatory state and/or the formation of CRP (75). A meta-analysis included 10 cross-sectional studies and showed no significant difference in the serum CRP level between AD patients and normal controls, whereas patients with mild and moderate AD had lower serum CRP levels as compared with the healthy controls by Mini-Mental State Examination scores (15), indicating that the diagnostic value of CRP for mild and moderate AD may be useful in clinical practice. Most studies support the reduced plasma CRP levels in mild and moderate AD patients and indicate its potential role as a representative systemic inflammatory marker for the diagnosis of AD. In addition, lower CRP levels are associated with more rapid cognitive and functional decline (76). The elevated CRP level was associated with an increased risk of AD (77), while such elevation appeared to diminish and fall below the level observed in nondemented controls after the clinical manifestation of the disease. In addition, the influence of CRP and homocysteine (Hcy) on patients suffering from AD was assessed and both CRP and Hcy were found to play no role in the development of AD (78). Strang et al. (79) recently demonstrated the association between mCRP in AD patients and beta-amyloid (A-β) plaques, which may induce the dissociation of pCRP into individual monomers. Moreover, basic research of human AD/stroke patients revealed that high mCRP levels from infarcted core regions were associated with the reduced expression of A-β/Tau, suggestive of the role of mCRP in promoting dementia after ischemia (80). Taken together, a direct functional effect elicited by CRP may, at least in part, explain the pathogenesis of AD.

CRP and PD

Parkinson’s disease is a neurodegenerative disorder pathologically characterized by dopaminergic neuronal death and the presence of Lewy bodies (81). Previous studies have highlighted the key role of neuroinflammatory reactions in the pathogenesis of PD and patients with PD were shown to exhibit higher levels of serum hs-CRP. Patients with more severe PD, classified according to the Hoehn–Yahr staging system, had significantly higher levels of hs-CRP than those at an earlier stage and non-Parkinson’s control subjects (82). A cross-sectional study suggested that CRP may play an important role in the development of PD and elevations in the plasma CRP level correlated with an increased risk of PD. Baseline CRP concentrations were recently shown to be associated with the risk of death and predicted life prognosis of patients with PD (81). A retrospective analysis further supported the association between baseline plasma CRP levels and motor deterioration and predicted motor prognosis in patients with PD; these associations were independent of sex, age, PD severity, dementia, and use of antiparkinsonian agents (83). Although formal demonstration of the mechanism of action of CRP in the pathogenesis of PD is currently lacking, there is a continuous increase in the experimental data, which is in line with the aforementioned concept.

Conclusion

As a nonspecific marker of inflammation, CRP plays a vital role in the monitoring of bacterial infection, inflammation, neurodegeneration, tissue injury, and recovery. Chronic inflammation may be a continuation of an acute or a prolonged low-grade form, which is increasingly recognized as an important issue with social and economic implications. CRP levels are observed to be increased during acute-phase inflammation as well as chronic inflammatory diseases. From both experimental and clinical data, increasing evidence suggest that elevated CRP concentrations are associated with an increased risk of CVD, T2DM, AD, hemorrhagic stroke, PD, and AMD. Moreover, CRP is not only an excellent biomarker of chronic inflammation but also acts as a direct participant in the pathological process (84). The differentiation between the physiological and pathophysiological CRP levels may allow better management of inflammation-related diseases. Although the clinical significance and underlying mechanisms of CRP in chronic inflammatory and neurodegenerative diseases are incompletely elucidated, further research is required in order to differentially characterize the roles of CRP isoforms (pCRP, facilitator, versus mCRP, effector) in chronic inflammation onset and progression. A better understanding of CRP activation and dissociation is essential to develop therapeutic strategies to minimize tissue injury, which may further improve the outcome of chronic inflammatory diseases.

Author Contributions

We affirm that all authors have contributed to, seen, and approved the final, submitted version of the manuscript and are willing to convey copy right to Frontiers in Immunology.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The reviewer JJA and handling Editor declared their shared affiliation.

Footnotes

Funding. This study was supported, in part, by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation (Nos. 81730057, 81401592), Beijing Nova Program (No. Z171100001117113), and National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2017YFC1103302).

References

- 1.Wu Y, Potempa LA, El Kebir D, Filep JG. C-reactive protein and inflammation: conformational changes affect function. Biol Chem (2015) 396:1181–97. 10.1515/hsz-2015-0149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cardoso FS, Ricardo LB, Oliveira AM, Horta DV, Papoila AL, Deus JR, et al. C-reactive protein at 24 hours after hospital admission may have relevant prognostic accuracy in acute pancreatitis: a retrospective cohort study. GE Port J Gastroenterol (2015) 22:198–203. 10.1016/j.jpge.2015.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu L, Shi Q, Shi M, Liu R, Wang C. Diagnostic value of PCT and CRP for detecting serious bacterial infections in patients with fever of unknown origin: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol (2017) 25:e61–9. 10.1097/PAI.0000000000000552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Memar MY, Alizadeh N, Varshochi M, Kafil HS. Immunologic biomarkers for diagnostic of early-onset neonatal sepsis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med (2017) 31:1–11. 10.1080/14767058.2017.1366984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pepys MB, Hirschfield GM. C-reactive protein: a critical update. J Clin Invest (2003) 111:1805–12. 10.1172/JCI200318921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nathan C, Ding A. Nonresolving inflammation. Cell (2010) 140:871–82. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nadrowski P, Chudek J, Skrzypek M, Puzianowska-Kuznicka M, Mossakowska M, Wiecek A, et al. Associations between cardiovascular disease risk factors and IL-6 and hsCRP levels in the elderly. Exp Gerontol (2016) 85:112–7. 10.1016/j.exger.2016.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agca R, Heslinga M, Kneepkens EL, Van Dongen C, Nurmohamed MT. The effects of 5-year etanercept therapy on cardiovascular risk factors in patients with psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol (2017) 44:1362–8. 10.3899/jrheum.161418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taheri S, Baradaran A, Aliakbarian M, Mortazavi M. Level of inflammatory factors in chronic hemodialysis patients with and without cardiovascular disease. J Res Med Sci (2017) 22:47. 10.4103/jrms.JRMS_282_15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weinstein G, Lutski M, Goldbourt U, Tanne D. C-reactive protein is related to future cognitive impairment and decline in elderly individuals with cardiovascular disease. Arch Gerontol Geriatr (2017) 69:31–7. 10.1016/j.archger.2016.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anchah L, Hassali MA, Lim MS, Ibrahim MI, Sim KH, Ong TK. Health related quality of life assessment in acute coronary syndrome patients: the effectiveness of early phase I cardiac rehabilitation. Health Qual Life Outcomes (2017) 15:10. 10.1186/s12955-016-0583-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Azadbakht L, Atabak S, Esmaillzadeh A. Soy protein intake, cardiorenal indices, and C-reactive protein in type 2 diabetes with nephropathy: a longitudinal randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Care (2008) 31:648–54. 10.2337/dc07-2065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seddon JM, Gensler G, Milton RC, Klein ML, Rifai N. Association between C-reactive protein and age-related macular degeneration. JAMA (2004) 291:704–10. 10.1001/jama.291.6.704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Towfighi A, Cheng EM, Ayala-Rivera M, McCreath H, Sanossian N, Dutta T, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a coordinated care intervention to improve risk factor control after stroke or transient ischemic attack in the safety net: secondary stroke prevention by uniting community and chronic care model teams early to end disparities (SUCCEED). BMC Neurol (2017) 17:24. 10.1186/s12883-017-0792-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gong C, Wei D, Wang Y, Ma J, Yuan C, Zhang W, et al. A meta-analysis of C-reactive protein in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen (2016) 31:194–200. 10.1177/1533317515602087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prins BP, Abbasi A, Wong A, Vaez A, Nolte I, Franceschini N, et al. Investigating the causal relationship of C-reactive protein with 32 complex somatic and psychiatric outcomes: a large-scale cross-consortium Mendelian randomization study. PLoS Med (2016) 13:e1001976. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abdul Rehman S, Khurshid Z, Hussain Niazi F, Naseem M, Al Waddani H, Sahibzada HA, et al. Role of salivary biomarkers in detection of cardiovascular diseases (CVD). Proteomes (2017) 5:21. 10.3390/proteomes5030021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fan J, Ma J, Xia N, Sun L, Li B, Liu H. Clinical value of combined detection of CK-MB, MYO, cTnI and plasma NT-proBNP in diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. Clin Lab (2017) 63:427–33. 10.7754/Clin.Lab.2016.160533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schulz S, Ludike H, Lierath M, Schlitt A, Werdan K, Hofmann B, et al. C-reactive protein levels and genetic variants of CRP as prognostic markers for combined cardiovascular endpoint (cardiovascular death, death from stroke, myocardial infarction, and stroke/TIA). Cytokine (2016) 88:71–6. 10.1016/j.cyto.2016.08.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vadakayil AR, Dandekeri S, Kambil SM, Ali NM. Role of C-reactive protein as a marker of disease severity and cardiovascular risk in patients with psoriasis. Indian Dermatol Online J (2015) 6:322–5. 10.4103/2229-5178.164483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ridker PM, Rifai N, Rose L, Buring JE, Cook NR. Comparison of C-reactive protein and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in the prediction of first cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med (2002) 347:1557–65. 10.1056/NEJMoa021993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FA, Genest J, Gotto AM, Jr, Kastelein JJ, et al. Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. N Engl J Med (2008) 359:2195–207. 10.1056/NEJMoa0807646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mirhafez SR, Ebrahimi M, Saberi Karimian M, Avan A, Tayefi M, Heidari-Bakavoli A, et al. Serum high-sensitivity C-reactive protein as a biomarker in patients with metabolic syndrome: evidence-based study with 7284 subjects. Eur J Clin Nutr (2016) 70:1298–304. 10.1038/ejcn.2016.111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ridker PM, Buring JE, Shih J, Matias M, Hennekens CH. Prospective study of C-reactive protein and the risk of future cardiovascular events among apparently healthy women. Circulation (1998) 98:731–3. 10.1161/01.CIR.98.8.731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Danesh J, Wheeler JG, Hirschfield GM, Eda S, Eiriksdottir G, Rumley A, et al. C-reactive protein and other circulating markers of inflammation in the prediction of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med (2004) 350:1387–97. 10.1056/NEJMoa032804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ridker PM. Clinical application of C-reactive protein for cardiovascular disease detection and prevention. Circulation (2003) 107:363–9. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000053730.47739.3C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bisoendial RJ, Kastelein JJ, Levels JH, Zwaginga JJ, Van Den Bogaard B, Reitsma PH, et al. Activation of inflammation and coagulation after infusion of C-reactive protein in humans. Circ Res (2005) 96:714–6. 10.1161/01.RES.0000163015.67711.AB [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elliott P, Chambers JC, Zhang W, Clarke R, Hopewell JC, Peden JF, et al. Genetic loci associated with C-reactive protein levels and risk of coronary heart disease. JAMA (2009) 302:37–48. 10.1001/jama.2009.954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park DW, Yun SC, Lee JY, Kim WJ, Kang SJ, Lee SW, et al. C-reactive protein and the risk of stent thrombosis and cardiovascular events after drug-eluting stent implantation. Circulation (2009) 120:1987–95. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.876763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liao JK. Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. Curr Atheroscler Rep (2009) 11:243–4. 10.1007/s11883-009-0037-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eisenhardt SU, Habersberger J, Murphy A, Chen YC, Woollard KJ, Bassler N, et al. Dissociation of pentameric to monomeric C-reactive protein on activated platelets localizes inflammation to atherosclerotic plaques. Circ Res (2009) 105:128–37. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.190611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Greenland P, Lloyd-Jones DM, Moss AJ. C-reactive protein levels and outcomes after statin therapy. N Engl J Med (2005) 352:1603–5; author reply 1603–5. 10.1056/NEJM200504143521519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wettero J, Nilsson L, Jonasson L, Sjowall C. Reduced serum levels of autoantibodies against monomeric C-reactive protein (CRP) in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Clin Chim Acta (2009) 400:128–31. 10.1016/j.cca.2008.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lange LA, Carlson CS, Hindorff LA, Lange EM, Walston J, Durda JP, et al. Association of polymorphisms in the CRP gene with circulating C-reactive protein levels and cardiovascular events. JAMA (2006) 296:2703–11. 10.1001/jama.296.22.2703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wensley F, Gao P, Burgess S, Kaptoge S, Di Angelantonio E, Shah T, et al. Association between C reactive protein and coronary heart disease: Mendelian randomisation analysis based on individual participant data. BMJ (2011) 342:d548. 10.1136/bmj.d548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kardys I, De Maat MP, Uitterlinden AG, Hofman A, Witteman JC. C-reactive protein gene haplotypes and risk of coronary heart disease: the Rotterdam study. Eur Heart J (2006) 27:1331–7. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller DT, Zee RY, Suk Danik J, Kozlowski P, Chasman DI, Lazarus R, et al. Association of common CRP gene variants with CRP levels and cardiovascular events. Ann Hum Genet (2005) 69:623–38. 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2005.00210.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pfutzner A, Schondorf T, Hanefeld M, Forst T. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein predicts cardiovascular risk in diabetic and nondiabetic patients: effects of insulin-sensitizing treatment with pioglitazone. J Diabetes Sci Technol (2010) 4:706–16. 10.1177/193229681000400326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwedler SB, Filep JG, Galle J, Wanner C, Potempa LA. C-reactive protein: a family of proteins to regulate cardiovascular function. Am J Kidney Dis (2006) 47:212–22. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.10.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhu JQ, Song WS, Hu Z, Ye QF, Liang YB, Kang LY. Traditional Chinese medicine’s intervention in endothelial nitric oxide synthase activation and nitric oxide synthesis in cardiovascular system. Chin J Integr Med (2015). 10.1007/s11655-015-1964-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Iida K, Tani S, Atsumi W, Yagi T, Kawauchi K, Matsumoto N, et al. Association of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and low-density lipoprotein heterogeneity as a risk factor of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease with triglyceride metabolic disorder: a pilot cross-sectional study. Coron Artery Dis (2017) 28:577–87. 10.1097/MCA.0000000000000521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Phosat C, Panprathip P, Chumpathat N, Prangthip P, Chantratita N, Soonthornworasiri N, et al. Elevated C-reactive protein, interleukin 6, tumor necrosis factor alpha and glycemic load associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus in rural Thais: a cross-sectional study. BMC Endocr Disord (2017) 17:44. 10.1186/s12902-017-0189-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ragy MM, Kamal NN. Linking senile dementia to type 2 diabetes: role of oxidative stress markers, C-reactive protein and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Neurol Res (2017) 39:587–95. 10.1080/01616412.2017.1312773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Rekeneire N, Peila R, Ding J, Colbert LH, Visser M, Shorr RI, et al. Diabetes, hyperglycemia, and inflammation in older individuals: the health, aging and body composition study. Diabetes Care (2006) 29:1902–8. 10.2337/dc05-2327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gorska-Ciebiada M, Saryusz-Wolska M, Borkowska A, Ciebiada M, Loba J. C-reactive protein, advanced glycation end products, and their receptor in type 2 diabetic, elderly patients with mild cognitive impairment. Front Aging Neurosci (2015) 7:209. 10.3389/fnagi.2015.00209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Andreozzi F, Succurro E, Mancuso MR, Perticone M, Sciacqua A, Perticone F, et al. Metabolic and cardiovascular risk factors in subjects with impaired fasting glucose: the 100 versus 110 mg/dL threshold. Diabetes Metab Res Rev (2007) 23:547–50. 10.1002/dmrr.724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sarangi R, Padhi S, Mohapatra S, Swain S, Padhy RK, Mandal MK, et al. Serum high sensitivity C-reactive protein, nitric oxide metabolites, plasma fibrinogen, and lipid parameters in Indian type 2 diabetic males. Diabetes Metab Syndr (2012) 6:9–14. 10.1016/j.dsx.2012.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou ZW, Ju HX, Sun MZ, Fu QP, Chen HM, Ji HB, et al. Serum fetuin-A levels are independently correlated with vascular endothelial growth factor and C-reactive protein concentrations in type 2 diabetic patients with diabetic retinopathy. Clin Chim Acta (2016) 455:113–7. 10.1016/j.cca.2016.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pleskovic A, Letonja MS, Vujkovac AC, Nikolajevic Starcevic J, Gazdikova K, Caprnda M, et al. C-reactive protein as a marker of progression of carotid atherosclerosis in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Vasa (2017) 46:187–92. 10.1024/0301-1526/a000614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.You YK, Huang XR, Chen HY, Lyu XF, Liu HF, Lan HY. C-reactive protein promotes diabetic kidney disease in db/db mice via the CD32b-Smad3-mTOR signaling pathway. Sci Rep (2016) 6:26740. 10.1038/srep26740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lai W, Tang Y, Huang XR, Ming-Kuen Tang P, Xu A, Szalai AJ, et al. C-reactive protein promotes acute kidney injury via Smad3-dependent inhibition of CDK2/cyclin E. Kidney Int (2016) 90:610–26. 10.1016/j.kint.2016.06.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tang Y, Fung E, Xu A, Lan HY. C-reactive protein and ageing. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol (2017) 44(Suppl 1):9–14. 10.1111/1440-1681.12758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yip JL, Khawaja AP, Chan MP, Broadway DC, Peto T, Tufail A, et al. Cross sectional and longitudinal associations between cardiovascular risk factors and age related macular degeneration in the EPIC-Norfolk eye study. PLoS One (2015) 10:e0132565. 10.1371/journal.pone.0132565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kurtul BE, Ozer PA. The relationship between neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and age-related macular degeneration. Korean J Ophthalmol (2016) 30:377–81. 10.3341/kjo.2016.30.5.377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Al-Zamil WM, Yassin SA. Recent developments in age-related macular degeneration: a review. Clin Interv Aging (2017) 12:1313–30. 10.2147/CIA.S143508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Colak E, Ignjatovic S, Radosavljevic A, Zoric L. The association of enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant defense parameters with inflammatory markers in patients with exudative form of age-related macular degeneration. J Clin Biochem Nutr (2017) 60:100–7. 10.3164/jcbn.16-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hector SM, Sorensen TL. Circulating monocytes and B-lymphocytes in neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Clin Ophthalmol (2017) 11:179–84. 10.2147/OPTH.S121332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ambreen F, Ismail M, Qureshi IZ. Association of gene polymorphism with serum levels of inflammatory and angiogenic factors in Pakistani patients with age-related macular degeneration. Mol Vis (2015) 21:985–99. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Haas P, Kubista KE, Krugluger W, Huber J, Binder S. Impact of visceral fat and pro-inflammatory factors on the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. Acta Ophthalmol (2015) 93:533–8. 10.1111/aos.12670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Soheilian R, Jabbarpour Bonyadi MH, Moein H, Babanejad M, Ramezani A, Yaseri M, et al. C-reactive protein and complement factor H polymorphism interaction in advanced exudative age-related macular degeneration. Int Ophthalmol (2016). 10.1007/s10792-016-0373-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chirco KR, Whitmore SS, Wang K, Potempa LA, Halder JA, Stone EM, et al. Monomeric C-reactive protein and inflammation in age-related macular degeneration. J Pathol (2016) 240:173–83. 10.1002/path.4766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cipriani V, Hogg RE, Sofat R, Moore AT, Webster AR, Yates JRW, et al. Association of C-reactive protein genetic polymorphisms with late age-related macular degeneration. JAMA Ophthalmol (2017) 135:909–16. 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2017.2191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bhutto IA, Baba T, Merges C, Juriasinghani V, Mcleod DS, Lutty GA. C-reactive protein and complement factor H in aged human eyes and eyes with age-related macular degeneration. Br J Ophthalmol (2011) 95:1323–30. 10.1136/bjo.2010.199216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Johnson PT, Betts KE, Radeke MJ, Hageman GS, Anderson DH, Johnson LV. Individuals homozygous for the age-related macular degeneration risk-conferring variant of complement factor H have elevated levels of CRP in the choroid. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2006) 103:17456–61. 10.1073/pnas.0606234103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Teasdale G, Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet (1974) 2:81–4. 10.1016/S0140-6736(74)91639-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hemphill JC, III, Bonovich DC, Besmertis L, Manley GT, Johnston SC. The ICH score: a simple, reliable grading scale for intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke (2001) 32:891–7. 10.1161/01.STR.32.4.891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Steiner T, Kaste M, Forsting M, Mendelow D, Kwiecinski H, Szikora I, et al. Recommendations for the management of intracranial haemorrhage – part I: spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage. The European Stroke Initiative Writing Committee and the writing committee for the EUSI executive committee. Cerebrovasc Dis (2006) 22:294–316. 10.1159/000094831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Di Napoli M, Elkind MS, Godoy DA, Singh P, Papa F, Popa-Wagner A. Role of C-reactive protein in cerebrovascular disease: a critical review. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther (2011) 9:1565–84. 10.1586/erc.11.159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Roudbary SA, Saadat F, Forghanparast K, Sohrabnejad R. Serum C-reactive protein level as a biomarker for differentiation of ischemic from hemorrhagic stroke. Acta Med Iran (2011) 49:149–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Di Napoli M, Godoy DA, Campi V, Del Valle M, Pinero G, Mirofsky M, et al. C-reactive protein level measurement improves mortality prediction when added to the spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage score. Stroke (2011) 42:1230–6. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.604983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Di Napoli M, Godoy DA, Campi V, Masotti L, Smith CJ, Parry Jones AR, et al. C-reactive protein in intracerebral hemorrhage: time course, tissue localization, and prognosis. Neurology (2012) 79:690–9. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318264e3be [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Di Napoli M, Parry-Jones AR, Smith CJ, Hopkins SJ, Slevin M, Masotti L, et al. C-reactive protein predicts hematoma growth in intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke (2014) 45:59–65. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Song IU, Chung SW, Kim YD, Maeng LS. Relationship between the hs-CRP as non-specific biomarker and Alzheimer’s disease according to aging process. Int J Med Sci (2015) 12:613–7. 10.7150/ijms.12742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Alexiou A, Soursou G, Yarla NS, Ashraf GM. Proteins commonly linked to autism spectrum disorder and Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Protein Pept Sci (2017). 10.2174/1389203718666170911145321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Iwamoto N, Nishiyama E, Ohwada J, Arai H. Demonstration of CRP immunoreactivity in brains of Alzheimer’s disease: immunohistochemical study using formic acid pretreatment of tissue sections. Neurosci Lett (1994) 177:23–6. 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90035-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Locascio JJ, Fukumoto H, Yap L, Bottiglieri T, Growdon JH, Hyman BT, et al. Plasma amyloid beta-protein and C-reactive protein in relation to the rate of progression of Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol (2008) 65:776–85. 10.1001/archneur.65.6.776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nilsson K, Gustafson L, Hultberg B. C-reactive protein level is decreased in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and related to cognitive function and survival time. Clin Biochem (2011) 44:1205–8. 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2011.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Devcic S, Glamuzina L, Ruljancic N, Mihanovic M. There are no differences in IL-6, CRP and homocystein concentrations between women whose mothers had AD and women whose mothers did not have AD. Psychiatry Res (2014) 220:970–4. 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.08.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Strang F, Scheichl A, Chen YC, Wang X, Htun NM, Bassler N, et al. Amyloid plaques dissociate pentameric to monomeric C-reactive protein: a novel pathomechanism driving cortical inflammation in Alzheimer’s disease? Brain Pathol (2012) 22:337–46. 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2011.00539.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Slevin M, Matou S, Zeinolabediny Y, Corpas R, Weston R, Liu D, et al. Monomeric C-reactive protein – a key molecule driving development of Alzheimer’s disease associated with brain ischaemia? Sci Rep (2015) 5:13281. 10.1038/srep13281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sawada H, Oeda T, Umemura A, Tomita S, Kohsaka M, Park K, et al. Baseline C-reactive protein levels and life prognosis in Parkinson disease. PLoS One (2015) 10:e0134118. 10.1371/journal.pone.0134118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Andican G, Konukoglu D, Bozluolcay M, Bayulkem K, Firtiina S, Burcak G. Plasma oxidative and inflammatory markers in patients with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neurol Belg (2012) 112:155–9. 10.1007/s13760-012-0015-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Umemura A, Oeda T, Yamamoto K, Tomita S, Kohsaka M, Park K, et al. Baseline plasma C-reactive protein concentrations and motor prognosis in Parkinson disease. PLoS One (2015) 10:e0136722. 10.1371/journal.pone.0136722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Vachatova S, Andrys C, Krejsek J, Salavec M, Ettler K, Rehacek V, et al. Metabolic syndrome and selective inflammatory markers in psoriatic patients. J Immunol Res (2016) 2016:5380792. 10.1155/2016/5380792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]