Abstract

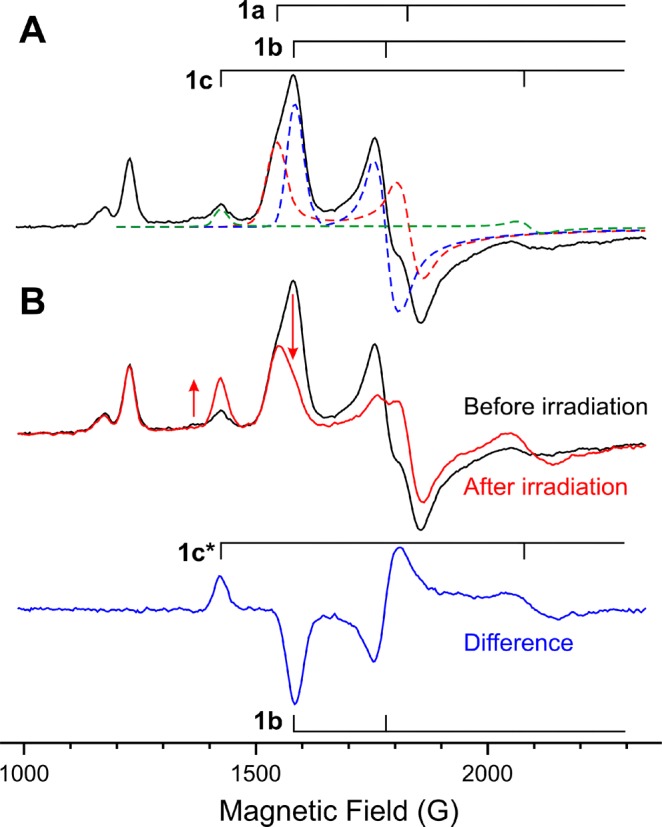

Early studies in which nitrogenase was freeze-trapped during enzymatic turnover revealed the presence of high-spin (S = 3/2) electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) signals from the active-site FeMo-cofactor (FeMo-co) in electron-reduced intermediates of the MoFe protein. Historically denoted as 1b and 1c, each of the signals is describable as a fictitious spin system, S′ = 1/2, with anisotropic g′ tensor, 1b with g′ = [4.21, 3.76, ?] and 1c with g′ = [4.69, ∼3.20, ?]. A clear discrepancy between the magnetic properties of 1b and 1c and the kinetic analysis of their appearance during pre-steady-state turnover left their identities in doubt, however. We subsequently associated 1b with the state having accumulated 2[e–/H+], denoted as E2(2H), and suggested that the reducing equivalents are stored on the catalytic FeMo-co cluster as an iron hydride, likely an [Fe–H–Fe] hydride bridge. Intra-EPR cavity photolysis (450 nm; temperature-independent from 4 to 12 K) of the E2(2H)/1b state now corroborates the identification of this state as storing two reducing equivalents as a hydride. Photolysis converts E2(2H)/1b to a state with the same EPR spectrum, and thus the same cofactor structure as pre-steady-state turnover 1c, but with a different active-site environment. Upon annealing of the photogenerated state at temperature T = 145 K, it relaxes back to E2(2H)/1b. This implies that the 1c signal comes from an E2(2H) hydride isomer of E2(2H)/1b that stores its two reducing equivalents either as a hydride bridge between a different pair of iron atoms or an Fe–H terminal hydride.

Short abstract

Nitrogenase exhibits two (S = 3/2) electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) signals from the active-site FeMo-co, denoted as 1b and 1c, when freeze-trapped during turnover. Low-temperature intra-EPR-cavity photolysis (4−12 K) corroborates an assignment of 1b as the state that has accumulated two reducing equivalents [E2(2H)] stored as a hydride bound to FeMo-co. Photolysis combined with thermal annealing at 145 K reveals that 1c also is an E2(2H) state but with a different binding mode for the hydride.

Introduction

In the kinetic model for biological nitrogen fixation (Figure 1), the reduction of N2 to 2NH3 by the enzyme nitrogenase requires that the catalytic FeMo-cofactor (FeMo-co) of the nitrogenase MoFe protein (Figure 2, left) accumulate 4[e–/H+] (E4(4H) intermediate) before the N≡N bond is cleaved and N2 is reduced to the level of diazene.1−3 We have shown that the E4(4H) “Janus intermediate” stores its accumulated four reducing equivalents as two [Fe–H–Fe] bridging hydrides, with two protons likely bound to sulfides, as illustrated in Figure 2.4−7 Storage of the reducing equivalents as bridging hydrides enables the four steps of electron delivery in Figure 1 to take place at the constant potential of the [4Fe4S] cluster of the electron-delivery nitrogenase Fe protein, which is in effect increased in magnitude by the accompanying hydrolysis of two adenosine triphosphate (ATP) molecules per electron. The storage as hydride bridges also decreases the tendency to “short-circuit” catalysis through sequential release of the equivalents in two steps of hydride protonation with release of H2 (Figure 1).8 The heart of the mechanism of N2 reduction is the step by which the enzyme in the stabilized E4(4H) state is activated to bind N2 and cleave the N≡N bond: reductive elimination (re) of the two hydrides of E4(4H) forms H2 bound to a doubly reduced, activated FeMo-co core; displacement of H2 by N2 then leads to the initial reduction of N2.4,9 Among the outstanding questions about the nitrogenase mechanism, we here address the identity of additional intermediate states associated with the electron-accumulation phase of the catalytic cycle (Figure 1).

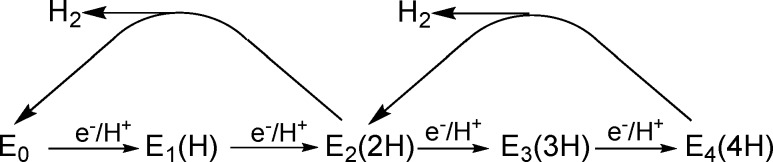

Figure 1.

Electron accumulation phase of the Lowe–Thorneley kinetic scheme for nitrogen fixation, including hydride protonation relaxation reactions that link the Kramers (half-integer spin) intermediates depicted below. En represents the MoFe protein state in which the catalytic FeMo-co cluster has accumulated n electrons from the Fe protein cycle plus n protons. The n = 4 state is activated by reductive elimination (re) of H2 to bind N2 and cleave the N≡N bond.

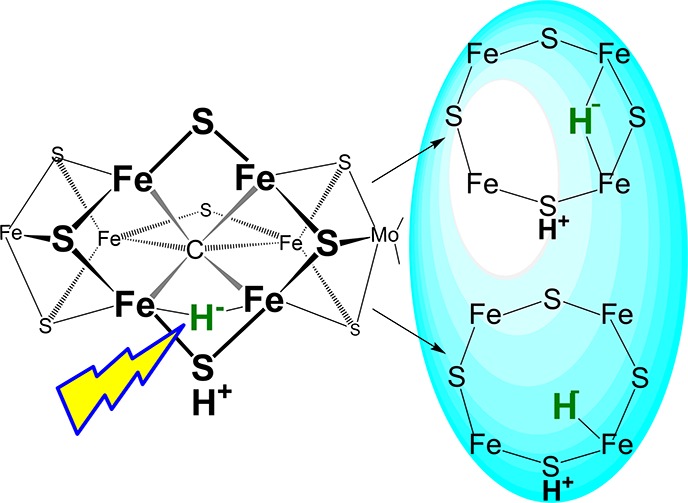

Figure 2.

(Left) Structure of FeMo-co as presented in the E4(4H) state, which contains four reducing equivalents stored as two [Fe–H–Fe] bridging hydrides on the reactive face, plus two sulfur-bound protons. (Right) Cartoon version of the FeMo-co reactive face.

Early studies in which nitrogenase was freeze-trapped during enzymatic turnover revealed the presence of high-spin (S = 3/2) EPR signals from the active-site FeMo-co in electron-accumulation intermediates of the MoFe protein. Historically denoted as 1b and 1c, each of the signals is describable as a fictitious spin system, S′ = 1/2, with anisotropic g′ tensors, 1b with g′ = [4.21, 3.76, ?] and 1c with g′ = [4.69, ∼3.20, ?].10 These signals are distinct from the high-spin (S = 3/2) signal of FeMo-co in the resting state of the enzyme, E0, denoted as 1a, with g′ = [4.32, 3.66, 2.01], and from the one arising from a recently discovered protonated form of E0, with g′ = [4.71, 3.30, 2.01].11 Although, as noted,11 this latter spectrum is quite similar to that of 1c, the two differ not least in that the 1c signal trapped during enzyme turnover and that from the protonated resting-state enzyme have different measured g′ values: g2′ = 3.20 for 1c and 3.30 for protonated E0; consequently, for clarity, we will here denote this latter state and its EPR signal as E0(H+)/1aH.

A clear discrepancy between the magnetic properties of 1b and 1c and the kinetic analysis of their appearance during pre-steady-state turnover under argon had left their identities in doubt. The kinetics of signal 1b formation indicated “that it arose after three electrons had been transferred to the MoFe protein”, and the kinetics further indicated that signal 1c is associated with the MoFe protein “in an even more-reduced redox state than 1b”. However, as those investigators well understood,10,12,13 FeMo-co of the E0 resting state is a Kramers state (odd-electron count, half-integer spin, S = 3/2), and only those electron-accumulation states in which FeMo-co had acquired either two or four electrons, E2(2H) or E4(4H), could exhibit such Kramers signals. The addition of three electrons to E0 FeMo-co would instead produce a non-Kramers system (even electron) that could not exhibit the half-integer spin signal 1b; as an argument against the possibility that only two of the three electrons went to FeMo-co, no EPR signal from the putative third electron could be detected. Nonetheless, in stepping back from this discrepancy, one possible assignment that was discussed for the 1b signal was as the E2(2H) intermediate, but perhaps more attractive was a conformer (possibly protonated) of FeMo-co at the E0 redox level13 presumably generated by the release of H2 from the E2 redox level. Considering the state associated with the 1c signal, if it is indeed even more reduced than 1b, its odd-electron signal must then associate it with either E2(2H) or E4(4H), but conversely it could be an E0 isomer/protonation state produced from a reduced state by the loss of reducing equivalents through H2 production.

We subsequently freeze-trapped nitrogenase during turnover of the MoFe V70I variant under argon and observed a low-spin (S = 1/2; g = [2.150, 2.007, 1.965]) FeMo-co signal7 that was identified as belonging to E4(4H) by cryoannealing, which showed that this state relaxes to the resting state E0 in two steps, each releasing H2 with a kinetic isotope effect, KIE ≳ 3 (Figure 1).6 Because annealing in the frozen solid precludes the addition of electrons to the MoFe protein, this implied that this state had accumulated four reducing equivalents, the E4(4H) state (Figure 1). Thereafter, we showed that the identical E4(4H) intermediate was trapped, along with E4(2N2H), when a wild-type (WT) enzyme was frozen during turnover under low N2 pressure. Cryoannealing of the freeze-trapped WT turnover sample further showed that E2(2H) is associated with the 1b signal.4,14 We proposed that E4(4H) converts to E2(2H)/1b during cryoannealing by the loss of H2 through the protonation of one bridging hydride by its “partner” proton, leaving the second bridging hydride/proton pair bound to the FeMo-co of E2(2H) (Figure 1).4,6,15,16 However, isomerization of the hydride during the process was not precluded.

The cryoannealing experiments also showed relaxation/loss of the 1c signal with a strong KIE, but because of the very low accumulation of this species during turnover, the product of this relaxation could not be determined, leaving the assignment of 1c unresolved. The similarity of the relaxation kinetics of 1c with those of the 1b → 1a conversion during annealing led us to tentatively propose that the intermediate corresponding to the 1c signal represents an E2(2H) isomer of the E2(2H)/1b state.14 However, an assignment of this Kramers signal to an isomer of E4(4H) or E0 was not precluded.

The goal of this study was to test the identification of the catalytic turnover intermediate 1b and to identify 1c. In principle, 1,2H ENDOR of the E2/1b state could test the proposed presence of an Fe hydride, either bridging or terminal, but the low accumulation of this state during turnover so far has forestalled such a test, while the even lower accumulation of 1c (Figure 3) totally precludes its examination by ENDOR. Instead, we have exploited the well-known photochemical reactivity of metal–hydrogen bonds in metal hydride complexes.17,18 We have already shown that the hydrides of the E4(4H) dihydride intermediate are photolabile upon excitation by 450 nm light at cryogenic temperatures,19,20 and we thus postulated that a single hydride in 1b, presumed to be a bridge, would likewise reveal itself by its photolability, in analogy to the well-known photoreactivity of the hydride in the Ni–C state of Ni–Fe hydrogenase.21 We here report that low-temperature (4–12 K) intra-EPR-cavity photolysis demonstrates the presence of such a photolabile hydride in 1b, thus corroborating its proposed assignment to an E2(2H) state in which the two reductive equivalents are stored as a hydride. Relaxation of the photoproduct during annealing of the still-frozen samples at more elevated temperatures leads to the assignment of 1c FeMo-co as an isomer of the E2(2H)/1b cofactor that also stores its two reducing equivalents as hydrides but with a different binding mode, either a bridge between a different pair of iron atoms or a terminal hydride.

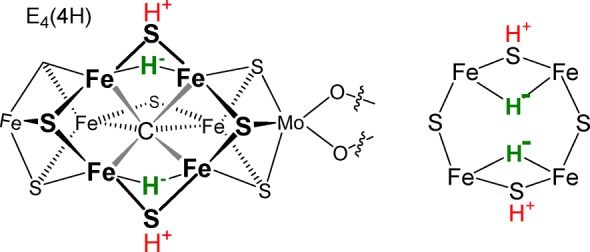

Figure 3.

(A) EPR spectrum of WT argon turnover in H2O with the shown decomposition into the three signals 1a, 1b, and 1c. (B) Changes in the EPR spectrum after 20 min of irradiation of the sample with 450 nm laser-diode light at 4 K. The lower trace is the difference of spectra before and after irradiation, and it shows only 1b and 1c* EPR features. Nonphotolabile species with EPR signals around 1200 G were previously suggested to come from an oxidized P-cluster in the S = 7/2 state.24

Materials and Methods

General Methods

All chemical reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Chemicals (St. Louis, MO) and used without further purification. Argon gas was purchased from Air Liquide America Specialty Gases LLC (Plumsteadville, PA) and passed through an activated copper catalyst to remove trace O2 contamination prior to use. The WT MoFe and Fe proteins used in this study were expressed and purified from Azotobacter vinelandii cells grown from stains DJ995 and DJ884, respectively.22,23 The purities of both proteins were confirmed to be greater than 95% by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) using Coomassie blue staining. Handling of proteins and buffers was done in septum-sealed serum vials under an argon atmosphere or on a Schlenk vacuum line. All liquids were transferred using gastight syringes. The “D2O” samples were prepared by exchanging and concentrating the MoFe protein in a turnover buffer prepared with D2O (D% ≥ 90%).

Preparation of Samples for EPR and Intra-EPR Cavity Photolysis

The samples for cryogenic photolysis and annealing after photolysis were prepared in a H2O or D2O solution containing a MgATP regeneration system (13 mM ATP, 15 mM MgCl2, 20 mM phosphocreatine, 2.0 mg/mL bovine serum albumin, and 0.3 mg/mL creatine phosphokinase) in a 200 mM 3-morpholinopropane-1-sulfonic acid buffer at pH or pD 7.4 with 50 mM dithionite under argon. The MoFe protein was added to a final concentration of ∼50 μM. Turnover of the enzyme was initiated by the addition of Fe protein to a final concentration of ∼75 μM. After about 25–30 s of incubation at room temperature, about 300 μL of the reaction mixture was transferred to a 4 mm calibrated X-band EPR tube and rapidly frozen in a hexane slurry (∼179 K) before being stored in liquid nitrogen (∼77 K). The samples were shipped on dry ice before being restored in liquid nitrogen for EPR, photolysis, and further experiments.

To test whether the 1c* species was trapped or not during nitrogenase turnover, the samples were prepared in a solution similar to that described above at pH or pD 7.3 with a final concentration of MoFe protein of ∼50 μM and a final concentration of Fe protein of ∼60 μM. To minimize any possible annealing processes, the reaction mixtures were incubated for ∼18 s at room temperature before being rapidly frozen in a pentane slurry (∼142 K), then transferred to liquid nitrogen within seconds, and stored and shipped in liquid nitrogen.

EPR Spectroscopy, Intra-EPR-Cavity Photolysis, and Cryoannealing

X-band EPR spectra were obtained on a Bruker ESP 300 spectrometer equipped with an Oxford Instruments ESR 900 continuous-liquid-helium-flow system. Spectra were recorded at the following conditions (if not specified): temperature, 3.8 K; microwave frequency, ∼9.36 GHz; microwave power, 2 mW; modulation amplitude, 9 G; time constant, 160 ms; field sweep speed, 28 G/s. Intra-EPR-cavity irradiation of a sample placed inside the cryostat was performed with a Thorlabs Inc. (Newton, NJ) PL450B, 450 nm, 80 mW Osram laser diode mounted on the cavity access port. Cryoannealing protocol involved multiple steps in which the sample frozen in liquid nitrogen was rapidly warmed by immersion in a pentane bath held at the annealing temperature for a fixed time and then cooled back to 77 K by immersion in liquid nitrogen. Overlapping signals 1a and 1b in the obtained spectra were decomposed as previously described.12 Data points of the E2/1b state were obtained as the intensity of the 1b signal g2 feature measured as the peak-to-peak height and normalized to its maximum before irradiation. Data points for changes in the 1c signal (denoted in the text as 1c*) were obtained as the intensity of the resolved g1 feature, normalized for kinetic plots as corresponding to the observed photoinduced 1b → 1c* conversion and shown after preirradiation background subtraction.

Results and Discussion

1b Photolysis

Figure 3A displays the low-field region of the EPR spectrum of WT nitrogenase freeze-quenched during turnover under argon. As indicated by the decomposition into component signals, the spectrum is a superposition of partially overlapping signals 1a and 1b, with an additional, weaker contribution from 1c. Figure 3B shows that intra-EPR-cavity 450 nm irradiation at 4 K causes a decrease in the E2/1b signal with a concomitant increase in the signal of E2/1c, while the E0/1a signal of the resting state is unchanged by the illumination.

Our earlier conclusion that 1b is the E2(2H) state with its reducing equivalents stored as a bound hydride4,6,9 is corroborated by the observation that the E2/1b state is photoactive, like inorganic hydride complexes,17,18 the [Fe–H–Fe] bridging hydrides of the E4(4H) state of nitrogenase,19,20 and the [Ni–H–Fe] bridging hydrides of the Ni–C state of NiFe hydrogenase.21 As noted above, the earlier cryoannealing study of E4(4H) implied that the hydride of E2/1b adopts a [Fe–H–Fe] bridging structure, and it will be thus described in this report. However, we note that this assignment will need further testing.

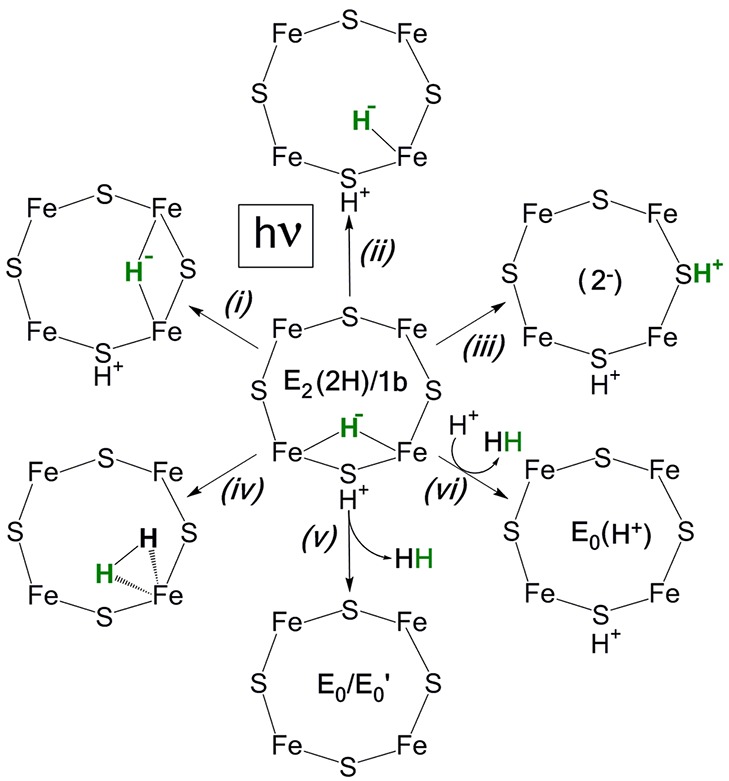

Photolysis of nitrogenase freeze-trapped during turnover converts E2(2H)/1b to a state with an identical EPR spectrum and thus the FeMo-co structure as 1c, but with a different active-site environment, as we discuss below. For clarity, we thus denote the photogenerated signal, 1c*. A number of possible hydride photoreactions of E2(2H)/1b can be envisaged, each leading to a different structure for the 1c/1c* FeMo-co cluster, as illustrated in Scheme 1:25 (i) isomerization of the hydride bridge; (ii) conversion to a terminal hydride; (iii) photochemical transfer of H+ to a sulfide, forming FeMo-co with a doubly reduced core and two H+ ions bound to sulfur atoms; photoinduced hydride protonation (iv) to generate an H2 complex of E0 or to form (v) E0 or a metastable resting-state conformer, denoted as E0′ upon H2 release or (vi) a protonated resting state, E0(H+). An analogous “wheel” could be drawn, assuming E2(2H)/1b to instead contain a terminal hydride.

Scheme 1. “Wheel” of Alternative Photoprocesses for a (Bridging) Hydride of E2(2H).

The observation that photolysis of 1b induces conversion to 1c, rather than causing an increase in the E0/1a signal, establishes that photolysis does not induce hydride protonation and conversion to E0/1a through the release of H2 (reaction v, Scheme 1). The EPR spectrum of the 1c photoproduct is identical with that of 1c freeze-trapped during turnover, so both signals must be associated with the same FeMo-co state. However, for reasons that will become clear below, we will henceforth denote the photogenerated signal as 1c*.

Photolysis Progress Curves

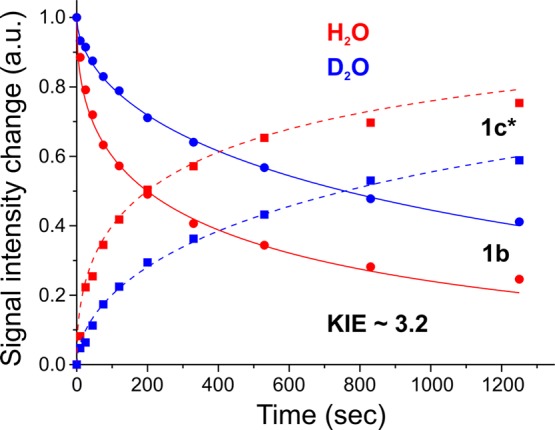

To obtain progress curves for both the photoinduced loss of 1b and the appearance of 1c*, we collected complete spectra at multiple times during irradiation and measured the intensities of the two species as a function of the photolysis time. As shown in Figure 4, at every time during photolysis, the increase in the 1c* signal corresponds to the loss of 1b, as normalized to the value of 1b at t = 0, and thus the rate parameters for the increase in the 1c signal necessarily correspond to those for the loss of 1b. This indicates that photoexcitation of 1b causes the 1b → 1c* conversion as a single kinetic step without buildup of an intermediate state. The progress curves are independent of the temperature for photolysis between 4 and 12 K (Figure S1), and a comparison of samples prepared in H2O and D2O, furthermore, shows that the rates of disappearance of 1b and the appearance of 1c* exhibit an equivalent photolysis KIE = τ(D2O)/τ(H2O) ∼ 3.2, indicating that the transformation involves proton(s) motion in the rate-limiting step.

Figure 4.

Progress curves of the 1b → 1c* conversion observed during irradiation with 450 nm diode-laser light at 4 K for WT argon turnover in H2O and D2O. Photoinduced decays of the EPR signal 1b are fitted as stretched exponentials, exp[−(t/τ)m] with τ = 452 s and m = 0.45 for H2O and τ = 1463 s and m = 0.56 for D2O. The change of the EPR signal 1c* is shown as corresponding to [1–1b(t)] kinetics (dotted lines), thus confirming that conversion corresponds to a single kinetic step.

For completeness, we note that this process is necessarily different from the photolytically induced reductive elimination of the two hydrides of E4(4H) to release H2.19,20 To complement this chemical difference, the latter process shows a much larger KIE ∼ 10, indicating the significance of tunneling in the H2 formation.

Thermal Relaxation

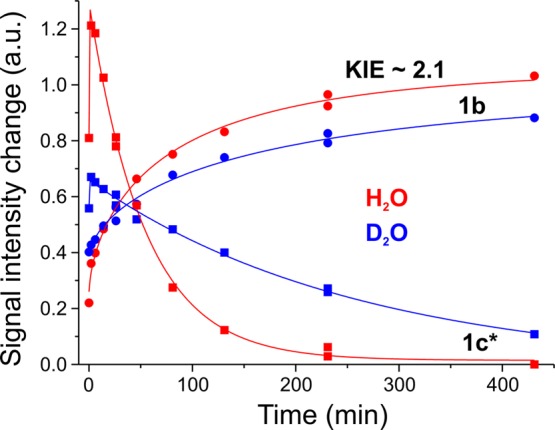

Discrimination among alternatives presented in Scheme 1 is achieved by analyzing the relaxation of the photogenerated 1c* during annealing of the still-frozen samples at more elevated temperatures. Frozen WT enzyme samples turned over in H2O and D2O buffers were freeze-trapped, irradiated with 450 nm light at 4–12 K, then annealed briefly in the solid state at successively higher temperatures, and cooled for examination at each step. This protocol showed that the 1c* product of 1b photolysis is stable at 77 K and quantitatively relaxes to 1b at 145 K (Figure 5). This temperature at which thermal relaxation occurs represents a key difference between the E2/1c state trapped during turnover and the 1c* state generated by photolysis: although the photogenerated state 1c* has an EPR spectrum identical with that of the 1c state trapped during turnover, the turnover-generated state only relaxes during cryoannealing at T ≳ 230 K, in contrast to relaxation of the photogenerated 1c* back to 1b at T = 145 K.

Figure 5.

Progress curves of the EPR signals 1b and 1c* during 145 K cryoannealing of photolyzed WT Ar turnover samples in H2O and D2O. Recoveries of the 1b signal are fitted as stretched exponentials with m = 0.65 and τ = 83 min for H2O and τ = 174 min for D2O. Solid lines showing changes of the 1c* signal are guides for the eye.

Because the identical E2/1c and E2/1c* EPR spectra imply that they share the same FeMo-co state, we infer that the significant difference in the relaxation temperatures is caused by a difference in the FeMo-co surroundings in the 1c and 1c* states. When intermediate 1c is trapped by freeze-quenching during turnover, the cofactor is surrounded by its own (cognate) equilibrium environment, but low-temperature irradiation of 1b instead generates 1c* with the cofactor trapped in the noncognate equilibrium environment of 1b. The two environments likely differ in the conformation and/or protonation state of the adjacent amino acid H195, which has long been assigned a role as a donor in proton delivery to the cofactor.26,27 We propose that the difference in the environments changes the relaxation activation energetics and, hence, the onset temperature for relaxation. In support of the importance of H195 in modulating the relaxation of 1c/1c*, we find that the 1b state trapped during turnover of the MoFe V70A/H195Q variant shows a much diminished photolability plausibly because enhanced relaxation diminishes the net quantum yield.

A detailed discussion of the relaxation kinetics of Figure 5 is presented below, after the assignment of 1c/1c*.

Identity of 1c/1c*

Regarding the nature of the FeMo-co state giving rise to the 1c/1c* EPR signal, the first thing to note is that this signal cannot come from a state more reduced than 1b. There is no possible means for photolysis of E2(2H)/1b in the frozen solid to introduce the two additional electrons needed to create a more reduced, EPR-active state. Conversely, 1c* cannot be a form of the resting-state FeMo-co, E0′, generated by photoinduced protonation of the 1b hydride by its partner protons bound to a sulfide, to form H2. Regardless of whether the resulting H2 remained bound as an H2 complex of FeMo-co in the resting oxidation state (Scheme 1, reaction iv) or was released to form a metastable E0 conformational state, E0′ (reaction v), the E0 oxidation state neither stably binds nor reacts with H2 and so could not regenerate E2(2H)/1b during annealing but instead would relax to E0. Photolysis could not have caused (vi) protonation of the hydride by a protein residue or a water, leaving the protonated resting state, E0(H+)/1aH. As noted above, the EPR signal of this state, although similar, is distinct from that of 1c/1c*, and in any case, for the above reasons, a protonated resting state could not regenerate E2(2H)/1b during annealing of the frozen solid.

These considerations indicate that 1c/1c* must be associated with an E2(2H) state that is isomeric to 1b, with 1c* generated by one of the hydride reactions, reactions i–iii of Scheme 1. Of these, reaction iii can also be ruled out. The 1c signal could not have been generated by photolytic conversion of a hydride to a proton bound to a sulfide, creating a doubly reduced FeMo-co core, because we recently20 detected the signal from this state; it is low-spin, S = 1/2, with g = [2.098, 2.000, 1.956], not S = 3/2 (S′ = 1/2) like 1c/1c*. By elimination, 1c/1c* must be a hydride isomer of E2/1b: photolysis of the [Fe–H–Fe] bridge of E2/1b produces E2/1c* with the hydride either bridging a different pair of iron atoms (reaction i) or having converted to a terminal hydride (reaction ii). An analogous wheel and hydride-isomer alternatives could be drawn for 1b with a terminal hydride.

Cryoannealing Relaxation Kinetics of Photogenerated 1c*

Considering the kinetics of thermal relaxation of 1c* → 1b (Figure 5) in more detail, the recovery of 1b at 145 K is monotonic and shows KIE ∼ 2. As is true during the photolysis process, at no time during the annealing does the amplitude of the E0/1a signal change, so the reducing equivalents originally stored in 1b are not lost during 1c* relaxation through the release of H2 with the formation of E0. In short, the major reaction during annealing is the 1c* → 1b thermal relaxation.

However, the progress curve for 1c* loss is more complicated than the curve for 1b recovery. The amplitude of the 1c* signal quickly rises during the first few minutes of annealing, and it then disappears with a rate constant and KIE similar to those of the 1b recovery. We attribute the initial phase in the 1c* progress curve to the rapid formation of 1c* by the relaxation of an additional minor photoproduct whose S = 1/2 EPR spectrum we have observed, namely, that photolysis of 1b not only generates 1c*, which anneals slowly back to 1b at ∼145 K, but also generates this minor product that relaxes rapidly at ∼145 K to 1c*, instead of returning to 1b.

Conclusions

Early work described two S = 3/2 EPR signals, 1b and 1c, associated with electron-accumulation intermediates in the nitrogenase catalytic cycle, En, 1 ≤ n ≤ 4 (Figure 1), but without determining the value of n or the structure for either.1,10 In the present work, low-temperature photolysis (4–12 K) of freeze-quenched turnover samples corroborates our assignment of 1b as the E2(2H) state, which has accumulated two reducing equivalents stored as a hydride bound to FeMo-co, likely as an [Fe–H–Fe] bridge. The photoproduct of 1b photolysis (denoted as 1c*) has an EPR spectrum, and thus a FeMo-co structure, identical with that of 1c. However, the two differ in their thermal relaxation, the result of differences in the active-site environment that arise from the different modes of preparation. Analysis of the relaxation of 1c* back to 1b at 145 K reveals that 1c/1c* also is an E2(2H) state in which FeMo-co stores the two reducing equivalents as a bound hydride but with a different binding mode for the hydride, most likely as a bridge between a different pair of iron atoms, or a terminal Fe–H hydride, as formed by photoreactions i or ii of Scheme 1. This finding can also be viewed in terms of an issue that we had discussed recently:9 how many electrons can be added to the metal-ion core of FeMo-co before hydride formation is required to enable further electron delivery from the “constant-potential” Fe protein? The assignments of 1b and 1c show that, upon the delivery of two electrons to the cluster [E2(2H)], the electrons are stored as a hydride, and the core formally remains at its resting-state valency. This allows the accumulation of the additional two electrons necessary for N2 reduction, which, in fact, are initially stored as the second hydride of E4(4H). Conversely, it confirms that the FeMo-co metal ion core cannot be doubly reduced except at the E4 state through the re of H2.4,9

Rapid freezing of turnover nitrogenase yields samples with significant, but relatively modest, differences in the occupancy ratio, 1b/1c ∼ (2–3)/1 (Figure 3A), which indicates that the 1c conformer is only slightly higher in energy, ∼1–2 kcal/mol. This suggests that the two hydride conformers are able to readily interconvert during fluid-solution turnover. In contrast, in freeze-trapped samples, we have only detected one form of the key E4(4H) Janus intermediate,4,6 suggesting that this single conformer is “tuned” to carry out re of the hydrides and the subsequent binding/reduction of N2 with a loss of H2.4,9

Acknowledgments

Support was provided by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, under Awards DE-SC0010687 and DE-SC0010834 to L.C.S. and D.R.D. and the National Institutes of Health (Grant GM111097 to B.M.H.).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.8b00271.

Temperature dependence of the photolysis time course (Figure S1) (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Burgess B. K.; Lowe D. J. Mechanism of Molybdenum Nitrogenase. Chem. Rev. 1996, 96, 2983–3012. 10.1021/cr950055x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorneley R. N. F.; Lowe D. J. Kinetics and Mechanism of the Nitrogenase Enzyme System. Metal Ions in Biology 1985, 7, 221–284. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson P. E.; Nyborg A. C.; Watt G. D. Duplication and Extension of the Thorneley and Lowe Kinetic Model for Klebsiella pneumoniae Nitrogenase Catalysis Using a Mathematica Software Platform. Biophys. Chem. 2001, 91, 281–304. 10.1016/S0301-4622(01)00182-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukoyanov D.; Khadka N.; Yang Z. Y.; Dean D. R.; Seefeldt L. C.; Hoffman B. M. Reductive Elimination of H2 Activates Nitrogenase to Reduce the N≡N Triple Bond: Characterization of the E4(4H) Janus Intermediate in Wild-Type Enzyme. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 10674–10683. 10.1021/jacs.6b06362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukoyanov D.; Yang Z.-Y.; Dean D. R.; Seefeldt L. C.; Hoffman B. M. Is Mo Involved in Hydride Binding by the Four-Electron Reduced (E4) Intermediate of the Nitrogenase MoFe Protein?. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 2526–2527. 10.1021/ja910613m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukoyanov D.; Barney B. M.; Dean D. R.; Seefeldt L. C.; Hoffman B. M. Connecting Nitrogenase Intermediates with the Kinetic Scheme for N2 Reduction by a Relaxation Protocol and Identification of the N2 Binding State. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007, 104, 1451–1455. 10.1073/pnas.0610975104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi R. Y.; Laryukhin M.; Dos Santos P. C.; Lee H. I.; Dean D. R.; Seefeldt L. C.; Hoffman B. M. Trapping H– Bound to the Nitrogenase FeMo-Cofactor Active Site During H2 Evolution: Characterization by ENDOR Spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 6231–6241. 10.1021/ja043596p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khadka N.; Milton R. D.; Shaw S.; Lukoyanov D.; Dean D. R.; Minteer S. D.; Raugei S.; Hoffman B. M.; Seefeldt L. C. The Mechanism of Nitrogenase H2 Formation by Metal-Hydride Protonation Probed by Mediated Electrocatalysis and H/D Isotope Effects. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 13518–13524. 10.1021/jacs.7b07311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman B. M.; Lukoyanov D.; Yang Z. Y.; Dean D. R.; Seefeldt L. C. Mechanism of Nitrogen Fixation by Nitrogenase: The Next Stage. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 4041–4062. 10.1021/cr400641x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe D. J.; Eady R. R.; Thorneley R. N. F. Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Studies on Nitrogenase of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Biochem. J. 1978, 173, 277–290. 10.1042/bj1730277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison C. N.; Spatzal T.; Rees D. C. Reversible Protonated Resting State of the Nitrogenase Active Site. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 10856–10862. 10.1021/jacs.7b05695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher K.; Newton W. E.; Lowe D. J. Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Analysis of Different Azotobacter vinelandii Nitrogenase MoFe-Protein Conformations Generated During Enzyme Turnover: Evidence for S = 3/2 Spin States from Reduced MoFe-Protein Intermediates. Biochemistry 2001, 40, 3333–3339. 10.1021/bi0012686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher K.; Lowe D. J.; Tavares P.; Pereira A. S.; Huynh B. H.; Edmondson D.; Newton W. E. Conformations Generated During Turnover of the Azotobacter Vinelandii Nitrogenase MoFe Protein and Their Relationship to Physiological Function. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2007, 101, 1649–1656. 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2007.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukoyanov D.; Yang Z. Y.; Duval S.; Danyal K.; Dean D. R.; Seefeldt L. C.; Hoffman B. M. A Confirmation of the Quench-Cryoannealing Relaxation Protocol for Identifying Reduction States of Freeze-Trapped Nitrogenase Intermediates. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53, 3688–3693. 10.1021/ic500013c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doan P. E.; Telser J.; Barney B. M.; Igarashi R. Y.; Dean D. R.; Seefeldt L. C.; Hoffman B. M. 57Fe ENDOR Spectroscopy and ‘Electron Inventory’ Analysis of the Nitrogenase E4 Intermediate Suggest the Metal-Ion Core of FeMo-Cofactor Cycles through Only One Redox Couple. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 17329–17340. 10.1021/ja205304t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman B. M.; Lukoyanov D.; Dean D. R.; Seefeldt L. C. Nitrogenase: A Draft Mechanism. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 587–595. 10.1021/ar300267m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perutz R. N.; Procacci B. Photochemistry of Transition Metal Hydrides. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 8506–8544. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perutz R. N. Metal Dihydride Complexes: Photochemical Mechanisms for Reductive Elimination. Pure Appl. Chem. 1998, 70, 2211–2220. 10.1351/pac199870112211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lukoyanov D.; Khadka N.; Dean D. R.; Raugei S.; Seefeldt L. C.; Hoffman B. M. Photoinduced Reductive Elimination of H2 from the Nitrogenase Dihydride (Janus) State Involves a FeMo-Cofactor-H2 Intermediate. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 2233–2240. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.6b02899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukoyanov D.; Khadka N.; Yang Z. Y.; Dean D. R.; Seefeldt L. C.; Hoffman B. M. Reversible Photoinduced Reductive Elimination of H2 from the Nitrogenase Dihydride State, the E4(4H) Janus Intermediate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 1320–1327. 10.1021/jacs.5b11650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubitz W.; Ogata H.; Rudiger O.; Reijerse E. Hydrogenases. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 4081–4148. 10.1021/cr4005814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen J.; Goodwin P. J.; Lanzilotta W. N.; Seefeldt L. C.; Dean D. R. Catalytic and Biophysical Properties of a Nitrogenase Apo-MoFe Protein Produced by a NifB-Deletion Mutant of Azotobacter vinelandii. Biochemistry 1998, 37, 12611–12623. 10.1021/bi981165b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seefeldt L. C.; Mortenson L. E. Increasing Nitrogenase Catalytic Efficiency for MgATP by Changing Serine 16 of Its Fe Protein to Threonine: Use of Mn2+ to Show Interaction of Serine 16 with Mg2+. Protein Sci. 1993, 2, 93–102. 10.1002/pro.5560020110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe D. J.; Fisher K.; Thorneley R. N. F. Klebsiella Pneumoniae Nitrogenase: Pre-Steady-State Absorbance Changes Show That Redox Changes Occur in the MoFe Protein That Depend on Substrate and Component Protein Ratio; a Role for P-Centers in Reducing Dinitrogen?. Biochem. J. 1993, 292, 93–98. 10.1042/bj2920093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- We note that this list of photoprocesses focuses on the hydride and does not include possible photoinduced cleavage of Fe–C or Fe–S bonds because FeMo-co in E0 is photostable. Likewise, we find that a proton bound to a sulfur of FeMo-co, as in the protonated E0 state of ref (11), is photostable.

- Fisher K.; Dilworth M. J.; Newton W. E. Differential Effects on N2 Binding and Reduction, HD Formation, and Azide Reduction with α-195His- and α-191Gln-Substituted MoFe Proteins of Azotobacter vinelandii Nitrogenase. Biochemistry 2000, 39, 15570–15577. 10.1021/bi0017834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilworth M. J.; Fisher K.; Kim C. H.; Newton W. E. Effects on Substrate Reduction of Substitution of Histidine-195 by Glutamine in the Alpha-Subunit of the MoFe Protein of Azotobacter vinelandii Nitrogenase. Biochemistry 1998, 37, 17495–17505. 10.1021/bi9812017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.