Abstract

Background

Nicaragua implemented an influenza vaccination program for pregnant women with high-risk obstetric conditions in 2007. In 2014, the recommendation of influenza vaccination expanded to include all pregnant women. Given the expansion in the recommendation of vaccination, we evaluated knowledge, attitudes and practices of pregnant women and their healthcare providers towards influenza vaccination and its recommendation.

Methods

We conducted surveys among pregnant women and their healthcare providers from June to August 2016 at two hospitals and 140 health facilities in Managua. The questions were adapted from the U.S. national CDC influenza survey and related to knowledge, attitudes and practices about influenza vaccination and barriers to vaccination. We analyzed reasons for not receiving vaccination among pregnant women as well as receipt of vaccination recommendation and offer by their healthcare providers.

Results

Of 1,303 pregnant women enrolled, 42% (5 4 5) reported receiving influenza vaccination in the 2016 season. Of those who reported not receiving vaccination, 46% indicated barriers to vaccination. Pregnant women who were vaccinated were more likely to be aware of the recommendation for vaccination and the risks of influenza illness during pregnancy and to perceive the vaccine as safe and effective, compared to unvaccinated pregnant women (p-values < 0.001). Of the 619 health workers enrolled, over 89% recalled recommending influenza vaccination to all pregnant women, regardless of obstetric risk. Of the 1,223 women who had a prenatal visit between the start date of the influenza vaccination and the time of interview, 44% recalled receiving a recommendation for influenza vaccination and 43% were offered vaccination. Vaccination rates were higher for those receiving a recommendation and offer of vaccination compared with those who received neither (95% vs 5%, p-value < 0.001).

Conclusion

Pregnant women in Managua had positive perceptions of influenza vaccine and were receptive to receiving influenza vaccination, especially after the offer and recommendation by their healthcare providers.

Keywords: Influenza vaccination, Knowledge, Attitudes, Practices, Pregnant women, Healthcare providers

1. Introduction

Maternal influenza immunization is a priority intervention for Nicaragua [1]. From 2007 to 2012, the Government of Nicaragua offered influenza vaccination to at-risk groups including pregnant women with obstetric risks. In 2013, Nicaragua expanded influenza vaccination to all pregnant women in the municipality of Managua [2], and since 2014, influenza vaccination was included in the annual vaccination campaign for all pregnant women nationwide. Antenatal care in Nicaragua is carried out at primary healthcare facilities; however, pregnant women diagnosed with high-risk obstetric conditions (HROC) may be referred to a tertiary hospital.

A study conducted in 2014 at two hospitals in the Department of Managua found that 55% of 3268 pregnant women were vaccinated against influenza, of which 8% (1 3 7) had been vaccinated in the first trimester of pregnancy, 61% (1093) in the second trimester and 31% (5 5 9) in the third trimester. The study noted that vaccinated pregnant women had more chronic diseases compared to unvaccinated ones (60% vs 53%, p < 0.01), suggesting that, in spite of the recent recommendation to vaccinate all pregnant women regardless of risk status, health workers continued to prioritize women with HROC [3]. In order to determine if healthcare providers were recommending influenza vaccination to all pregnant women regardless of HROC status, we conducted a follow-up survey of knowledge, attitudes and practices of health personnel and pregnant women in Managua.

2. Methods

2.1. Survey design, hypothesis and sample size

We evaluated knowledge, attitudes and practices of pregnant women and their healthcare providers towards influenza vaccination and its recommendation through a cross-sectional survey. We hypothesized that there were differences in the implementation of the recommendation of influenza vaccination among pregnant women based on HROC status [3]. Hypothesizing that 61% of pregnant women with HROC and 53% without HROC would receive influenza vaccination, and assuming that 57% of pregnant women in our study population would have HROC [3], we calculated a sample size of 1274 women using a formula to detect differences between proportions. Likewise, hypothesizing that 61% of pregnant women with HROC and 53% without HROC would receive influenza vaccination recommendation from a healthcare provider, we calculated a sample size of 600 healthcare providers. We applied a significance level of 0.05 and a statistical power of 0.8 for both calculations.

2.2. Survey for pregnant women

Between June 29 and August 9, 2016--months when influenza typically circulates in Nicaragua [4]--we approached all women who attended prenatal and postpartum visits at the German Nicaraguan Hospital, the Bertha Calderón Roque Hospital and 140 primary healthcare facilities in Managua until sample size was achieved. Women had to have been pregnant during the months of May and June and residents of the Department of Managua in order to participate in the survey.

The questionnaire included demographic information (i.e., age, ethnicity, education level, number of children, marital status, employment status, rural or urban housing area). Adapted from the U.S. national CDC influenza survey [5], the survey instrument included questions about vaccination status in the 2016 season, (from May 23, 2016, the start date of influenza vaccination in the 2016 season, through the time of interview), reasons for not receiving influenza vaccination, barriers to vaccination, knowledge about vaccination recommendation, perceived risk of influenza illness, attitudes about vaccine safety and effectiveness and recall of vaccination recommendation or offer of vaccination at prenatal care visits after May 23, 2016. Additional questions about pregnancy included presence of HROC during pregnancy, diagnosis of HROC, date of last menstrual period, date of first prenatal visit and number of prenatal visits attended.

2.3. Survey for healthcare providers attending to pregnant women

Surveys of health personnel were conducted from August 3 to 26, 2016 at the German Nicaraguan Hospital, the Bertha Calderón Roque Hospital and at 140 primary healthcare facilities serving pregnant women in Managua. As an inclusion criterion, the respondent had to have provided care to pregnant women in their health facility since May 23, 2016. The survey instrument, also adapted from the U.S. national CDC influenza survey [5], included questions about demographics (i.e. age, sex, and education level), knowledge of influenza vaccination policy for pregnant women, perceived risk of influenza disease during pregnancy and attitudes about influenza vaccine safety and effectiveness.

2.4. Data analysis

We present frequencies and proportions of sociodemographic characteristics, HROC status in pregnancy, influenza vaccination in previous pregnancy and receipt of influenza vaccination recommendation and/or offer during prenatal visits. Data analysis for pregnant women was stratified by vaccination status in the 2016 season. The analysis of reasons for not receiving influenza vaccination in the 2016 season was stratified by HROC and by age group (<25, 25 to 34 and >35 years old). We also analyzed healthcare providers’ influenza vaccination recommendation and offer during prenatal visits after May 23, 2016, stratified by age, HROC and number of prenatal care visits. We calculated the percentages of vaccination by receipt of influenza vaccination recommendation and/or offer of vaccination. We used Pearson X2 test to assess significance in the difference between proportions. For those who attended a prenatal care visit after May 23, 2016, we also analyzed for associations between participant characteristics (age group, ethnicity, education, employment, civil status, number of children), antenatal care characteristics (number of antenatal care visits, presence of high-risk obstetric conditions, receipt of influenza vaccination in previous pregnancy) and receipt of influenza vaccination recommendation and offer from healthcare provider by bivariate and multivariate analyses. We present unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (ORs and AORs) with 95% confidence intervals.

Descriptive analyses for healthcare provider survey data are presented in frequencies and proportions.

We used the R software (3.4.0 version) and Microsoft Excel® 2016 for all data analysis.

2.5. Ethics

This program evaluation was approved as public health practice by the Institutional Review Board of the Ministry of Health of Nicaragua. Following Nicaragua law, we obtained informed consent directly from survey participants who were married or who were single and ≥16 years old. For those under 16 years old and unmarried, we obtained their assent and informed consent from their parents or legal guardians.

3. Results

3.1. Survey for pregnant women

A total of 1303 pregnant women participated in the survey. All approached and eligible women agreed to participate in the survey. The majority of pregnant women (59%) surveyed were less than 25 years of age (range: 13–44, median age: 23); 93% self-identified as mestizo (mixed Amerindian and white) ethnicity and 88% had a high school or lower educational level. Most were homemakers (71%), lived with a partner or spouse (87%), and were multiparous (60%). (Table 1) Approximately 97% reported having at least one prenatal visit, and of these, 62% reported that their first prenatal visit occurred in the first trimester. Forty-two percent had a HROC (supplementary Table).

Table 1.

Characteristics of pregnant women by influenza vaccination status (n = 1303), survey among pregnant women, Managua, Nicaragua June-August 2016.

| n (%) | Survey among pregnant women (n = 1303) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Vaccinated n (%) | Unvaccinated n (%) | p-value | ||

| All | 1303 (100) | 545 (42) | 758 (58) | |

| Age group (in years) | ||||

| <25 (range: 13–24) | 769 (59) | 329 (60) | 440 (58) | 0.48 |

| 25–34 | 438 (34) | 181 (33) | 257 (34) | |

| ≥35 (range: 35–44) | 96 (7) | 35 (6) | 61 (8) | |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Mixed | 1208 (93) | 501 (92) | 707 (93) | 0.60 |

| White | 87 (7) | 40 (7) | 47 (6) | |

| African descent | 3 (0.2) | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Native American | 4 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) | 3 (0.4) | |

| Education | ||||

| None | 22 (2) | 10 (2) | 12 (2) | 0.02 |

| Primary incomplete | 145 (11) | 59 (11) | 86 (11) | |

| Primary complete | 144 (11) | 77 (14) | 67 (9) | |

| Secondary incomplete | 551 (42) | 235 (43) | 316 (42) | |

| Secondary complete | 288 (22) | 113 (21) | 175 (23) | |

| Technical studies | 8 (0.6) | 1 (0.2) | 7 (1) | |

| University studies | 177 (11) | 49 (9) | 95 (13) | |

| Employment | ||||

| In payroll | 79 (6) | 29 (5) | 50 (7) | 0.31 |

| Self-employed | 146 (11) | 57 (10) | 89 (12) | |

| Unemployed <1 year | 35 (3) | 10 (2) | 25 (3) | |

| Unemployed >1 year | 5 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | 4 (0.5) | |

| Housewife | 922 (71) | 400 (73) | 522 (69) | |

| Student | 112 (9) | 46 (8) | 66 (9) | |

| Cannot work | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | |

| Civil status | ||||

| Married | 268 (21) | 117 (21) | 151 (20) | 0.17 |

| Living with partner | 862 (66) | 357 (65) | 505 (67) | |

| Single | 167 (13) | 66 (12) | 101 (13) | |

| Separated | 3 (0.2) | 3 (0.5) | 0 (0) | |

| Refused | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | |

| Number of children | ||||

| 1 | 512 (39) | 223 (41) | 289 (38) | 0.59 |

| 2 a 4 | 708 (54) | 289 (53) | 419 (55) | |

| >4 | 83 (6) | 33 (6) | 50 (7) | |

| Number of ANC visits in current pregnancy | ||||

| None | 39 (3) | 4 (1) | 35 (5) | <0.001 |

| 1 to 2 visits | 1004 (77) | 418 (77) | 586 (77) | |

| 3 to 4 visits | 228 (18) | 107 (20) | 121 (16) | |

| >4 | 28 (2) | 15 (3) | 13 (2) | |

| Trimester of first ANC | ||||

| 1st | 741 (62) | 312 (61) | 429 (63) | 0.79 |

| 2nd | 364 (31) | 161 (32) | 203 (30) | |

| 3rd | 82 (7) | 35 (7) | 47 (7) | |

| High-risk obstetric conditions | ||||

| Yes | 542 (42) | 198 (36) | 344 (45) | 0.002 |

| No | 756 (58) | 345 (63) | 411 (54) | |

| Previously vaccinated during pregnancy | ||||

| Yes | 279 (68) | 172 (32) | 107 (14) | <0.001 |

| No | 891 (21) | 314 (58) | 577 (76) | |

| Do not know | 70 (5) | 22 (4) | 48 (6) | |

| Reported a vaccination date | ||||

| Yes | – | 544 (99.8) | – | |

| No | – | 1 (0.2) | – | |

| Trimester of vaccination | ||||

| 1st | – | 23 (4) | – | |

| 2nd | – | 76 (14) | – | |

| 3rd | – | 409 (75) | – | |

ANC = antenatal care.

Fewer than half of the women (42%; 545/1303) reported receiving influenza vaccination in the 2016 season (Table 1). Among those who reported being vaccinated, 32% reported receiving influenza vaccination in a previous pregnancy compared with 14% among those unvaccinated (p-value < 0.001). The majority (75%) of pregnant women vaccinated during 2016 received vaccination in the third trimester, followed by 14% in the second trimester vaccination and 4% in the first trimester. Almost all vaccinated pregnant women (99%) had at least one prenatal visit versus 95% of unvaccinated pregnant women. Most vaccinated pregnant women did not have a HROC (63%).

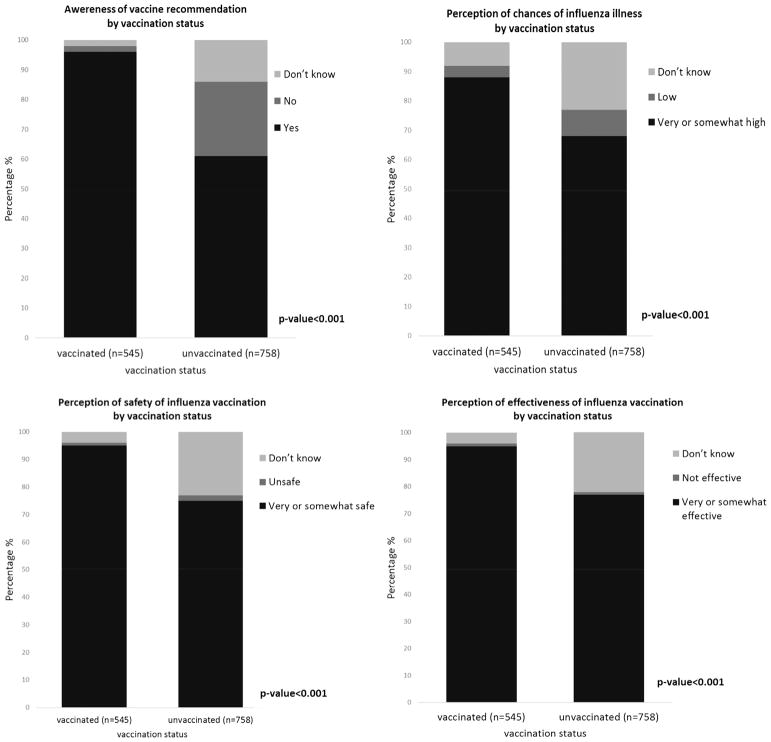

Among unvaccinated women, 25% were unaware that influenza vaccination was recommended for them, compared to 2% among the vaccinated (p-value < 0.001). Likewise, a higher percentage of the vaccinated women perceived a high or very high risk of influenza disease during pregnancy (88%) as compared to those unvaccinated (68%, p-value < 0.001). Vaccinated women also perceived that influenza vaccine was somewhat or very safe (95%) and effective (95%) compared to unvaccinated women (77% and 75%, respectively, p-values < 0.001, Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Knowledge and attitudes of pregnant women regarding influenza vaccination, by vaccination status, Managua, Nicaragua June-August 2016.

Barriers to vaccination were commonly (46%, 350/758) cited as reasons for being unvaccinated against influenza. Specific barriers mentioned were: “I was not aware of influenza vaccination/no one told me” (n = 311), “Vaccine was not available at the health facility when I had my appointments” (n = 28), “Healthcare providers advised me not to get vaccinated” (n = 9), “Other reasons related to barriers to vaccination, availability and lack of time to go for vaccination” (n = 2). One percent (7/758) reported concerns about the safety of the vaccine and 3% (25/758) reported not needing or wanting it while 34% (261/758) answered “Don’t know” to why they had not received vaccination (Table 2).

Table 2.

Reasons for not receiving an influenza vaccination (n = 758) among unvaccinated pregnant women surveyed, Managua, Nicaragua June-August 2016.

| All n (%) | Main reason

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccine safety concerns* n (%) | Do not need/want** n (%) | Barrier to vaccination*** n (%) | Do not know n (%) | Other n (%) | p-value† | ||

| All | 758 (100) | 7 (1) | 25 (3) | 350 (46) | 261 (34) | 66 (9) | |

| Age (years) | |||||||

| <25 | 440 (58) | 5 (1) | 15 (3) | 204 (46) | 161 (37) | 28 (6) | 0.22 |

| 25–34 | 257 (34) | 2 (1) | 8 (3) | 113 (40) | 83 (32) | 32 (12) | |

| ≥35 | 61 (8) | 0 (0) | 2 (3) | 33 (54) | 17 (28) | 6 (10) | |

| High-risk obstetric conditions | |||||||

| Yes | 344 (45) | 4 (1) | 12 (3) | 152 (44) | 132 (38) | 27 (8) | 0.31 |

| No | 411 (54) | 3 (1) | 13 (3) | 198 (48) | 126 (31) | 39 (9) | |

Vaccine safety concerns included “concerns about getting the flu from vaccination”, “allergic reaction to vaccination”, “concerns about side effects from vaccination”, “afraid of needles”, “other concerns about safety/side effects”.

Do not want/need included “I never get the flu”, “because I already had the flu”, “not a high risk or priority group”, “vaccine did not change from last year”, “other ‘I don’t want/need the vaccine’ reason”.

Barriers to vaccination included “vaccine was not available at the health facility when I had my appointments”, “healthcare providers advised me not get vaccinated”, “I was not aware of influenza vaccination/no one told me”, “other reasons related to barriers to vaccination, availability, or time”.

X2 test.

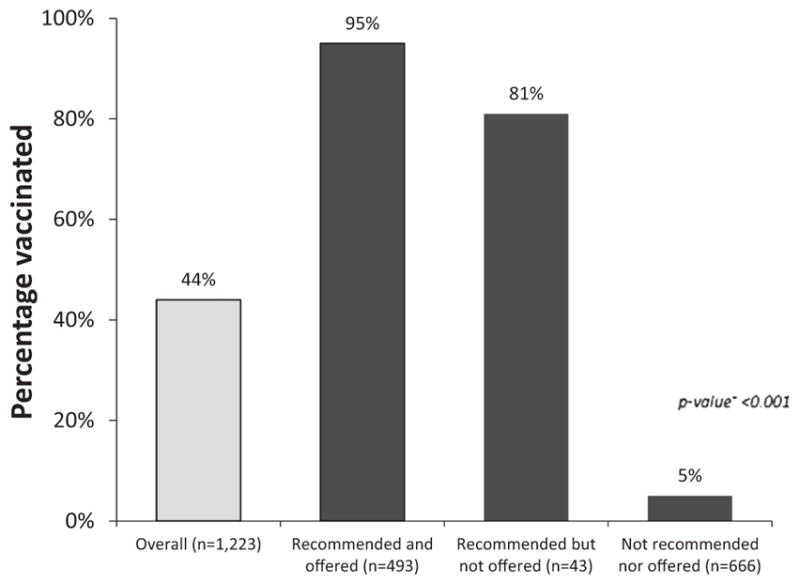

Among pregnant women who reported attending prenatal care since May 23, 2016 (n = 1223), 44% and 43% received a recommendation and an offer of influenza vaccination, respectively (Table 3). However, only 39% of women with a HRCO received a recommendation and 39% an offer of vaccination compared with 47% and 46%, respectively, among those without a HRCO (p-values < 0.01 and 0.04, respectively). Overall, 44% of pregnant women who reported attending prenatal care since the start of influenza vaccination on May 23, 2016 (n = 1223) were vaccinated against influenza; among those who recalled a recommendation and offer of influenza vaccination, 95% (470/493) were vaccinated. In addition, 81% (35/43) of those who recalled a recommendation but not an offer of vaccination were vaccinated compared to 5% (32/666) of those who did not receive a vaccination recommendation or offer (p-value < 0.0 01, Fig. 2).

Table 3.

Characteristics of pregnant women who received prenatal care since the start date of influenza vaccination (n = 1223), by receipt of health care provider recommendation and offer of influenza vaccination, Managua, Nicaragua June-August 2016.

| All n (%) | Provider recommendation

|

Provider offer

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Received recommendation for influenza vaccination n (%) | Did not receive recommendation for influenza vaccination n (%) | p-value | Were offered influenza vaccination n (%) | Were not offered influenza vaccination n (%) | p-value | ||

| All | 1223 (1 0 0) | 536 (44) | 651 (53) | 527 (43) | 680 (56) | ||

| Age (years) | |||||||

| <25 | 719 (59) | 314 (44) | 384 (53) | 0.80 | 304 (42) | 403 (56) | 0.8 |

| 25–34 | 416 (34) | 186 (45) | 216 (52) | 184 (44) | 228 (55) | ||

| ≥35 | 88 (7) | 36 (41) | 51 (58) | 39 (44) | 49 (56) | ||

| High-risk obstetric conditions | |||||||

| Yes | 514 (42) | 201 (39) | 302 (59) | <0.01 | 203 (39) | 305 (59) | 0.04 |

| No | 705 (58) | 333 (47) | 347 (49) | 322 (46) | 373 (53) | ||

| Number of ANC visits | |||||||

| 1–2 | 967 (79) | 419 (43) | 519 (54) | 0.48 | 408 (42) | 548 (57) | 0.21 |

| ≥3 | 252 (21) | 116 (46) | 129 (51) | 118 (47) | 129 (51) | ||

Note: Numbers and percentages reflect available information. Percentages may not sum to 100% due to rounding and missing data.

Fig. 2.

Vaccination rates of pregnant women, by influenza vaccination recommendation and/or offer, Managua, Nicaragua June-August 2016. Note: Numbers and percentages reflect available information. †X2 test. This table refers to the following questions from the survey: 1) “Since May 23rd, 2016 have you had a flu vaccination?”; 2) “Since May 23rd, 2016 have you visited a doctor or other health care professional for antenatal care”; 3) “At one or more of these visits, did your doctor or other health professional recommend that you should get a flu vaccination, should not get a flu vaccination, or did not give a recommendation either way?”; 4) “During your visits to the doctor or other health professional, did your doctor or other health professional offer the flu vaccination to you?”.

In addition, we did not find an association between age group, ethnicity, employment, civil status, number of children, number of antenatal visits and receipt of influenza vaccination in 2016 in either the unadjusted and adjusted analyses. Having technical education or university studies as well as presence of obstetric conditions were negatively associated with receipt of influenza vaccination in the unadjusted analyses; however, this association was not found in the adjusted analyses. Likewise, receipt of influenza vaccination in a previous pregnancy was positively associated with receipt of influenza vaccination in the unadjusted analysis, but this association did not persist in the adjusted analysis. Receipt of recommendation and offer of influenza vaccination from a healthcare provider were strongly associated in both the unadjusted and adjusted analyses (p-value < 0.001; Table 4).

Table 4.

Relationship between participant and prenatal care characteristics and influenza vaccination during pregnancy, bivariate and multivariable analysis, Managua, Nicaragua, June – August 2016 (n = 1223).

| Vaccinated in 2016 (1 = Yes; 0 = No) | Unadjusted OR | 95% CI | Adjusted OR** | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | ||||

| Age group (Ref=<25 years) | ||||

| 25–34 vs Ref | 0.99 | (0.76, 1.29) | 0.67 | (0.31, 1.45) |

| ≥35 vs Ref | 0.86 | (0.54, 1.38) | 0.40 | (0.10, 1.62) |

| Ethnicity (Ref = Mixed) | ||||

| White/(Native American/ African descendent vs Ref | 1.23 | (0.78, 1.94) | 2.01 | (0.64, 6.31) |

| Education (Ref = None/Incomplete primary school) | ||||

| Complete primary school vs Ref | 1.39 | (0.85, 2.29) | 2.25 | (0.67, 7.5) |

| Incomplete secondary school vs Ref | 0.92 | (0.62, 1.35) | 1.11 | (0.41, 2.99) |

| Completed secondary school vs Ref | 0.75 | (0.49, 1.15) | 1.34 | (0.44, 4.1) |

| Technical education/University studies vs Ref | 0.47 | (0.28, 0.79)* | 0.99 | (0.26, 3.78) |

| Employment (Ref = In Payroll/Self-employed) | ||||

| Unemployed/Cannot work vs Ref | 0.81 | (0.35, 1.86) | 0.46 | (0.06, 3.24) |

| Housewife vs Ref | 1.32 | (0.94, 1.84) | 1.52 | (0.62, 3.74) |

| Student vs Ref | 0.91 | (0.54, 1.53) | 1.90 | (0.48, 7.57) |

| Civil status (Ref = Married) | ||||

| Living with partner vs Ref | 0.88 | (0.65, 1.2) | 0.73 | (0.32, 1.69) |

| Single/Separated vs Ref | 0.87 | (0.57, 1.33) | 0.40 | (0.13, 1.26) |

| Number of children (Ref = 1) | ||||

| 2–4 vs Ref | 1.04 | (0.80, 1.34) | 1.17 | (0.53, 2.54) |

| >4 vs Ref | 1.10 | (0.65, 1.86) | 1.21 | (0.25, 5.98) |

| Number of antenatal visits (Ref = 1–2 visits) | ||||

| 3–4 vs Ref | 1.22 | (0.89, 1.67) | 1.28 | (0.59, 2.77) |

| >4 vs Ref | 1.26 | (0.52, 3.06) | 2.29 | (0.25, 21.36) |

| High-risk obstetric conditions (yes vs no) | 0.66 | (0.51, 0.84)* | 0.78 | (0.41, 1.48) |

| Previously vaccinated during pregnancy (yes vs no) | 2.82 | (2.11, 3.78)* | 1.07 | (0.50, 2.31) |

| Received recommendation for influenza vaccination from provider (yes vs no) | 398.29 | (224.75, 705.81)* | 74.11 | (36.63, 149.94)* |

| Received offer of influenza vaccination from provider (yes vs no) | 164.53 | (102.56, 263.95)* | 15.69 | (7.45, 33.03)* |

p-value < 0.01.

Adjusted for age group, ethnicity, education, employment, civil status, number of children, number of antenatal visits, presence of high-risk obstetric conditions, previous vaccination during pregnancy, receipt of recommendation for influenza vaccination from provider and receipt of offer of influenza vaccination from provider.

3.2. Survey for healthcare providers attending pregnant women

We collected 619 surveys among healthcare providers (Table 5). All approached and eligible healthcare providers agreed to participate in the survey. Most of the healthcare providers surveyed were female (82%), and 67% had a university degree. Most healthcare providers knew of the recommendation for influenza vaccination in pregnant women (94%), perceived that unvaccinated pregnant women were at very or somewhat high risk for influenza disease (85%), and believed influenza vaccines to be very or somewhat effective (98%) and very or somewhat safe (97%). Approximately 40% of healthcare providers surveyed did not know that influenza vaccination was recommended for all pregnancies regardless of trimester. Only 5% of healthcare providers recommended against vaccination of pregnant women with HROCs, and 1% recommended against vaccination of healthy pregnant women. A higher percentage of healthcare providers recommended influenza vaccination for healthy women compared to those with HROCs (94% vs 89%, p-value = 0.01).

Table 5.

Characteristics of health care providers and their knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding influenza vaccination, Managua, Nicaragua June-August 2016.

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| All | 619 (100) |

| Age group (years) | |

| <30 (range: 17–29) | 217 (35) |

| 30–50 | 251 (41) |

| ≥50 (range: 35–62) | 150 (24) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 111 (18) |

| Female | 508 (82) |

| Education | |

| Technician | 42 (7) |

| University Degree | 359 (58) |

| University Degree and specialization | 32 (5) |

| University Diploma and Master | 27 (4) |

| Other | 159 (26) |

| If patient does not have a high-risk obstetric condition | |

| I recommend influenza vaccination | 580 (94) |

| I recommend not to receive influenza vaccination | 8 (1) |

| I do not give any recommendation | 30 (5) |

| Do not know | |

| If patient has a high-risk obstetric condition | |

| I recommend influenza vaccination | 549 (89) |

| I recommend not to receive influenza vaccination | 29 (5) |

| I do not give any recommendation | 34 (5) |

| Do not know | |

| Knowledge of influenza vaccination recommendation for pregnant women | |

| Yes | 580 (94) |

| No | 12 (2) |

| Do not know | 25 (4) |

| Refused | 4 (0.2) |

| Perception of influenza illness among pregnant women | |

| Very or somewhat high | 527 (85) |

| Very or somewhat low | 87 (14) |

| Do not know | 5 (1) |

| Influenza vaccine effectiveness | |

| Very or somewhat effective | 606 (98) |

| Not effective | 8 (1) |

| Do not know | 5 (1) |

| Influenza vaccine safety | |

| Very or somewhat safe | 598 (97) |

| A little or not safe | 12 (2) |

| Do not know | 8 (1) |

| Refused | 1 (0.1) |

| Trimester of recommendation for influenza vaccination among pregnant women | |

| Any trimester | 371 (60) |

| Starting second trimester | 197 (32) |

| Starting third trimester | 20 (3) |

| Do not know | 28 (5) |

| Refused | 5 (0.3) |

4. Discussion

Overall, we observed a high acceptance of influenza vaccination among pregnant women in Managua, just as we did in our survey in 2013 [2]. Specifically, of the 40% that received a recommendation and an offer of influenza vaccination, 95% were vaccinated; however, among those who received neither a vaccination recommendation nor an offer, only 5% were vaccinated. This finding supports the literature that healthcare provider recommendation and offer of influenza vaccination are leading predictors of vaccination among pregnant women [6–12] and substantiates that healthcare providers with up-to-date knowledge, good practices and attitudes towards influenza vaccination foster acceptance of the vaccine among pregnant women [13,14].

In the adjusted analysis, receipt of influenza vaccination recommendation and vaccination offer are the main predictors for influenza vaccination during pregnancy; associations between influenza vaccination during pregnancy and other predictors such as education, number or antenatal visits or influenza vaccination in previous pregnancy were seen in the unadjusted analyses but did not persist in the adjusted analysis. Our findings are consistent with studies from countries where the vaccination coverage rates are higher when there is receipt of vaccine recommendation, especially when receiving both a recommendation and an offer of vaccination [15–17]. Specifically, in the United States during the 2014–15 influenza season, vaccination coverage among pregnant women who received an influenza vaccination recommendation and a vaccine offer was approximately 68% compared to 34% among those who received a recommendation but not an offer, and 8.5% among those who did not receive a recommendation nor an offer [16].

As of 2014, 29 out of 45 countries/territories in the Americas, including Nicaragua, prioritize pregnant women for influenza vaccination [18–21]. Despite this high rate of prioritization in the region, more work can be done to communicate these important messages. In this analysis, we observed that, overall, pregnant women and healthcare providers were well informed about the risk of influenza disease during pregnancy; however, there were still women who did not perceive influenza as a health risk for pregnant women, which is important to note because influenza illness among pregnant women is a risk factor for hospitalization [22–26]. In addition, only 60% of healthcare providers surveyed recommended influenza vaccination in all trimesters of gestation; fortunately, <5% recommended not to vaccinate pregnant women. It is necessary to remind and update local healthcare providers about the risk of contracting influenza during pregnancy and extend risk communication to the population.

This work had some limitations. For the survey of pregnant women, we hypothesized that a higher proportion of pregnant women would have received influenza vaccination. However, we learned through post-survey investigation that the two hospitals from which we recruited most of the pregnant women, did not receive influenza vaccine, which we understand led some health-care providers to not recommend or offer influenza vaccination, meaning that women would have to visit primary healthcare facilities to receive influenza vaccination. In addition, ideally, all of the recruitment of pregnant women would have taken place at primary healthcare facilities, which received influenza vaccine; however, that was logistically difficult, so it was not carried out. We had hypothesized that healthcare providers would continue to prioritize HROC women even after the Ministry of Health changed the recommendation to all pregnant women. However, we observed the opposite; pregnant women without HROC were more likely to be recommended for influenza vaccination compared to pregnant women with HROC. This finding should be interpreted with caution because of the bias resulting from recruitment of pregnant women at hospitals which generally attend to more HROC patients than primary healthcare facilities. Furthermore, for both surveys, we performed convenience samples of pregnant women and healthcare providers and, therefore, the sample may not be representative of the population of Managua. In addition, we are not able to make comparisons between results obtained from pregnant women and those obtained from healthcare providers as most of women were interviewed at two hospitals whereas most of healthcare providers were interviewed at primary health-care facilities. Despite these limitations, we obtained important information on pregnant women and healthcare providers that can be used to inform education campaigns.

This evaluation led to the recommendation that hospitals serving as a reference facility for both prenatal visits and delivery for pregnant women with high-risk obstetric conditions be included in the influenza vaccine distribution plan. In addition, it was recommended that all personnel who provide care for pregnant women receive information and updates on influenza vaccination recommendations and policies for pregnant women to close knowledge gaps and provide pregnant women with the most up-to-date information.

In conclusion, pregnant women in Managua had positive perceptions of influenza vaccine and were receptive to receiving influenza vaccination, especially after the offer and recommendation by their healthcare providers. Efforts to educate pregnant women and healthcare providers, as well as provide an uninterrupted supply of vaccine at all health centers providing prenatal care, will likely improve influenza vaccination coverage in Managua.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

This publication was supported by Cooperative Agreements 5U38OT000216-04 and NU51IP000873, funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

We would like to thank the Nicaraguan Ministry of Health, the Public Health Surveillance Directorate, the Expanded Program on Immunizations, the Local System of Primary Care in Managua (SILAIS Managua), members of the evaluation team, the participant hospitals in Managua--Hospital Bertha Calderón Roque and Hospital Alemán Nicaragüense, and the participants who agreed to be interviewed.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.05.013.

Footnotes

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). The content of this article has not been previously presented.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors do not have an association that might pose a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Ministerio de Salud de Nicaragua, Ley General de Salud y Reglamento de Salud. MODELO DE SALUD FAMILIAR Y COMUNITARIA. Mayo; Republica de Nicaragua: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arriola CS, Vasconez N, Thompson M, Mirza S, et al. Factors associated with a successful expansion of influenza vaccination among pregnant women in Nicaragua. Vaccine. 2016;34(8):1086–90. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.12.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arriola CS, Vasconez N, Thompson MG, Olsen SJ, et al. Association of influenza vaccination during pregnancy with birth outcomes in Nicaragua. Vaccine. 2017;35(23):3056–63. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.04.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Durand LO, Cheng PY, Palekar R, Clara W, et al. Timing of influenza epidemics and vaccines in the American tropics, 2002–2008, 2011–2014. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2016;10(3):170–5. doi: 10.1111/irv.12371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Flu Survey Questionnaire. 2014 [cited 2017 June 20]; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nis/data_files.htm.

- 6.Bodeker B, Betsch C, Wichmann O. Skewed risk perceptions in pregnant women: the case of influenza vaccination. BMC Public Health. 2015;16:1308. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2621-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kissin DM, Power ML, Kahn EB, Williams JL, et al. Attitudes and practices of obstetrician-gynecologists regarding influenza vaccination in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(5):1074–80. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182329681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Panda B, Stiller R, Panda A. Influenza vaccination during pregnancy and factors for lacking compliance with current CDC guidelines. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011;24(3):402–6. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2010.497882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Regan AK, Mak DB, Hauck YL, Gibbs R, et al. Trends in seasonal influenza vaccine uptake during pregnancy in Western Australia: Implications for midwives. Women Birth. 2016;29(5):423–9. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stark LM, Power ML, Turrentine M, Samelson R, et al. Influenza vaccination among pregnant women: patient beliefs and medical provider practices. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2016;2016:3281975. doi: 10.1155/2016/3281975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vilca LM, Verma A, Buckeridge D, Campins M. A population-based analysis of predictors of influenza vaccination uptake in pregnant women: The effect of gestational and calendar time. Prev Med. 2017;99:111–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong VW, Fong DY, Lok KY, Wong JY, et al. Brief education to promote maternal influenza vaccine uptake: A randomized controlled trial. Vaccine. 2016;34(44):5243–50. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blanchard-Rohner G, Meier S, Ryser J, Schaller D, et al. Acceptability of maternal immunization against influenza: the critical role of obstetricians. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25(9):1800–9. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2012.663835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eppes C, Wu A, Cameron KA, Garcia P, et al. Does obstetrician knowledge regarding influenza increase HINI vaccine acceptance among their pregnant patients? Vaccine. 2012;30(39):5782–4. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arriola CS, Mercado-Crespo MC, Rivera B, Serrano-Rodriguez R, et al. Reasons for low influenza vaccination coverage among adults in Puerto Rico, influenza season 2013–2014. Vaccine. 2015;33(32):3829–35. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.06.093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ding H, Black CL, Ball S, Donahue S, et al. Influenza vaccination coverage among pregnant women-United States, 2014–15 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(36):1000–5. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6436a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kennedy ED, Ahluwalia IB, Ding H, Lu PJ, et al. Monitoring seasonal influenza vaccination coverage among pregnant women in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(3 Suppl):S9–S16. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.06.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ortiz JR, Perut M, Dumolard L, Wijesinghe PR, et al. A global review of national influenza immunization policies: analysis of the 2014 WHO/UNICEF Joint Reporting Form on immunization. Vaccine. 2016;34(45):5400–5. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ropero-Alvarez AM, El Omeiri N, Kurtis HJ, Danovaro-Holliday MC, et al. Influenza vaccination in the Americas: progress and challenges after the 2009 A(H1N1) influenza pandemic. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(8):2206–14. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2016.1157240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ropero-Alvarez AM, Kurtis HJ, Danovaro-Holliday MC, Ruiz-Matus C, et al. Expansion of seasonal influenza vaccination in the Americas. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:361. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ropero-Alvarez AM, Whittembury A, Kurtis HJ, dos Santos T, et al. Pandemic influenza vaccination: lessons learned from Latin America and the Caribbean. Vaccine. 2012;30(5):916–21. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.11.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Creanga AA, Johnson TF, Graitcer SB, Hartman LK, et al. Severity of 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus infection in pregnant women. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(4):717–26. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181d57947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fell DB, Azziz-Baumgartner E, Baker MG, Batra M, et al. Influenza epidemiology and immunization during pregnancy: Final report of a World Health Organization working group. Vaccine. 2017;35(43):5738–50. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris JW. Influenza ocurring in pregnant women. JAMA. 1919:978–80. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jamieson DJ, Honein MA, Rasmussen SA, Williams JL, et al. H1N1 2009 influenza virus infection during pregnancy in the USA. Lancet. 2009;374(9688):451–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mertz D, Geraci J, Winkup J, Gessner BD, et al. Pregnancy as a risk factor for severe outcomes from influenza virus infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Vaccine. 2017;35(4):521–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.