Abstract

Background

This is a dosimetric comparative study intended to establish appropriate low-to-intermediate dose-constraints for the rectal wall (Rwall) in the context of a randomized phase-II trial on urethra-sparing stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) for prostate cancer. The effect of plan optimization on low-to-intermediate Rwall dose and the potential benefit of an endorectal balloon (ERB) are investigated.

Methods

Ten prostate cancer patients, simulated with and without an ERB, were planned to receive 36.25Gy (7.25Gyx5) to the planning treatment volume (PTV) and 32.5Gy to the urethral planning risk volume (uPRV). Reference plans with and without the ERB, optimized with respect to PTV and uPRV coverage objectives and the organs at risk dose constraints, were further optimized using a standardized stepwise approach to push down dose constraints to the Rwall in the low to intermediate range in five sequential steps to obtain paired plans with and without ERB (Vm1 to Vm5). Homogeneity index for the PTV and the uPRV, and the Dice similarity coefficient (DSC) for the PTV were analyzed. Dosimetric parameters for Rwall including the median dose and the dose received by 10 to 60% of the Rwall, bladder wall (Bwall) and femoral heads (FHeads) were compared. The monitor units (MU) per plan were recorded.

Results

Vm4 reduced by half D30%, D40%, D50%, and Dmed for Rwall and decreased by a third D60% while HIPTV, HIuPRV and DSC remained stable with and without ERB compared to Vmref. HIPTV worsened at Vm5 both with and without ERB. No statistical differences were observed between paired plans on Rwall, Bwall except a higher D2% for Fheads with and without an ERB.

Conclusions

Further optimization to the Rwall in the context of urethra sparing prostate SBRT is feasible without compromising the dose homogeneity to the target. Independent of the use or not of an ERB, low-to-intermediate doses to the Rwall can be significantly reduced using a four-step sequential optimization approach.

Keywords: Stereotactic body radiotherapy, Endorectal balloon, Dosimetric optimization, Prostate cancer, Urethra sparing

Background

Stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) for prostate cancer is emerging as a safe treatment option for patients with localized disease [1]. Clinical interest in extreme hypofractionated treatments results from estimated low α/β ratio values for prostate tumors (i.e. ≈1.5Gy) compared with the nearby organs at risk (OAR); rectum, urethra and bladder, with α/β values of 3–5 Gy [2, 3]. A treatment strategy, such as intentionally under-dosing areas of potentially lower tumor burden, for example the periurethral transitional zone of the prostate, may be used to reduce the risk of radiation induced urinary toxicity [4–6]. However, the risk of rectal toxicity is a major concern when designing prostate dose-escalation studies. Both conventionally fractionated radiotherapy and SBRT studies have shown that higher dose to the rectum correlates with increased rectal toxicity [7]. Minimizing the dose to the rectum, over the whole range from low to high doses, could impact the quality of life [8].

Guidelines for dose constraints for OAR for prostate SBRT are either inexistent or not well established. For the most widely used SBRT schedule (7.25 Gy, 5 fractions), recommended dose constraints have been published by King et al. [1]. These are the constraints that have been adopted by the Novalis Circle Phase II Trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT01764646). Dose to the rectum can be reduced by using either a software-based technique i.e. dosimetry plan optimization with the goal of reducing the dose to the rectal wall (Rwall) [9], and/or gadget-based techniques, such as the use of an inflated endorectal balloon (ERB) [10] or prostate-rectal spacers [11–13].

We aimed to perform a dosimetric comparative study undertaken in the context of a randomized phase-II trial on urethra-sparing SBRT for prostate cancer. The principal goal of the study was to determine the optimal strategy for minimizing the low-to-intermediate-dose regions of the Rwall, with the secondary goal of assessing the potential dosimetric benefit for the Rwall of using an ERB compared to no-ERB.

Methods

Ten prostate cancer patients (cT1-3a N0 M0, Roach index for lymph-node involvement < 20%), treated between February 2013 and June 2014, were selected for the study. They were part of a population of 170 patients recruited in nine countries as part of a prospective multicentric randomized phase-II trial of short vs. protracted urethral-sparing SBRT for localized prostate cancer. This study concerns the first 10 consecutive patients recruited in one of the institution. They were all simulated, planned, and treated with an ERB inflated with 100 ml air [14].

For each patient, a first computed tomography simulation scan (CTsim) was acquired with an ERB, followed by a second CTsim without the ERB. Planning CTs were acquired with axial slices of 2-mm thickness. A pediatric urinary catheter was introduced for accurate urethra delineation. A rigid registration with a pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) acquired on a flat table with the patient in the same treatment position and with an ERB was performed for definition of clinical target volume (CTV) and urethra in the CTsim dataset acquired with ERB. On the other hand, the diagnostic MRI, realized without ERB, was used for contouring purposes for the second CTsim dataset acquired without ERB.

A rectal enema was performed at home or in the clinic, based on patient preference, at the CTsim and during the treatment course prior to insertion of the ERB (6 times in total). The enema was well tolerated overall and if necessary a second enema was performed if the rectum was not completely emptied. Patients were positioned in the supine position and immobilized with the Combifix™ system. They were instructed to drink 600–700 mL of water one hour before the procedure, immediately after emptying their bladders. Three to four fiducials were implanted transrectally in the prostate under ultrasound guidance by an experienced uro-radiologist a minimum of seven days prior to the CTsim acquisition for image-guidance.

The planning risk volume for the urethra (uPRV) consisted of the urethra plus a surrounding isotropic expansion of 3 mm inside the transitional zone (maximum axial uPRV size 1 cm). The CTV included the prostate, with or without the seminal vesicles (6 and 4 patients, respectively). The planning target volume (PTV) was defined as the CTV plus a 5 mm isotropic expansion in all directions except posteriorly, where a 3 mm expansion was used, excluding the uPRV. The absolute volumes of the PTV with and without ERB were similar for each patient: median 96.4 cm3 (range, 68.0–143.6) with the ERB and 92.4 cm3 (range 57.0–131.7) without. A 3 mm thick Rwall was defined on each CT from the lowest level of the ischial tuberosities to the rectosigmoid flexure. A 5 mm thick bladder wall (Bwall) and both proximal femurs (Fheads) were contoured on the corresponding CT axial slices. All contours were drawn in the Eclipse (Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, USA) treatment planning system (TPS) version 10 by the same radiation oncologist following the male pelvis normal tissue RTOG consensus contouring guidelines [15].

Plans were optimized with the progressive resolution optimizer (PRO v10.0.28 in Eclipse) and calculated with the analytical anisotropic algorithm (AAA v10.0.28). The treatment was delivered in two full volumetric modulated arcs (VMAT) with 6 MV beams using an accelerator equipped with a 2.5 mm leaf width HDMLC. The SBRT protocol prescribed 36.25 Gy in 5 fractions to the PTV, with a dose limit of 32.5 Gy to the uPRV, resulting in a biologically equivalent dose in 2 Gy per fraction (EQD2) of approximately 90 Gy to the PTV (α/β = 1.5Gy) and 62 Gy to the uPRV (α/β = 3). The plan normalization goal aimed to achieve 98% of the PTV receiving 95% of the prescribed dose (D98% = 34.4Gy) with a maximum of 2% of PTV receiving no more than 107% of the prescribed dose (D2% ≤ 38.8Gy). Similarly, the goal for the uPRV was D98% ≥ 30.9 Gy (95% of 32.5Gy) and D2% ≤ 35.8 Gy (107% of 32.5Gy). Dose constraints for the Rwall were V36.25 Gy < 5%, V32.6 Gy < 10% V29 Gy < 20% (Table 1); for the Bwall the constraints were V36.25 Gy < 10%, V32.6 Gy < 20%, and V18.1 Gy < 50%; while for the Fheads the constraint was D2% ≤ 18.1 Gy.

Table 1.

Original dose-constraints for Rwall as used for the paired reference plans (Vmref) and the proposed additional dose-constraints based on the paired plans Vm4

| Volume | Original dose-constraints (Vmref) | Additional dose-constraints after optimization (Vm4) |

|---|---|---|

| Rwall | V36.25 Gy < 5% | V13.1 Gy ≤ 30% |

| V32.6 Gy < 10% | V7.2 Gy ≤ 40% | |

| V29 Gy < 20% | Dmed ≤6.5 Gy |

For each patient a pair of reference plans (Vmref) was created: one with ERB and one without ERB. The reference plans were optimized in order to respect the PTV and uPRV coverage objectives and the OAR dose constraints, without any additional sparing on the Rwall in the low or intermediate dose range. The optimization parameters were adapted separately on an individual basis for each patient/ERB combination to produce the reference plans. Then the intermediate-and-low dose sparing of the Rwall was forced further by adding three additional dose-volume optimization (DVO) constraints on the Rwall (D2%, D10% and D15%) and by decreasing their value at each steps. These constraints were assigned a constant weight. Their initial values were set to start in the intermediate dose range (D2% = 18Gy, D10% = 15Gy and D15% = 13Gy) down to low dose range (6, 3 and 1Gy, respectively) for the last optimization step. The additional DVO constraints were similar with and without ERB and applied for each patient. This resulted in a total of 120 plans (12 plans per patient - 6 with ERB and 6 without ERB) ranging from the reference plans (Vmref), optimized with the initial dose constraints, to extreme optimization plans (Vm1 to Vm5), optimized with additional DVO objectives on the Rwall. The homogeneity index for the PTV (HIPTV) and the uPRV (HIuPRV) was determined using: (D2%–D98%)/D50%. The Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) between the PTV and the volume encompassed by the 95% isodose line (V95%) was calculated as the ratio of their intersection and their union. DSC = (V95%∩PTV)/(V95%∪ PTV). Dosimetric parameters for the PTV, uPRV, and OAR were calculated. In addition, the median dose (Dmed) to the Rwall, as well as the dose received by 10 to 60% of the Rwall volume, in increments of 10% (D10% to D60%), were analyzed. The total number of monitor units (MU) was recorded.

The comparison of the dosimetric parameters with and without ERB at each step of the optimization was performed using the Friedman non-parametric analysis of variance. Post-hoc tests were performed according to the Dunn-Bonferroni procedure, with p-values adjusted for multiple comparisons. Statistics were computed using SPSS version 22; p-values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant (two-sided tests).

Results

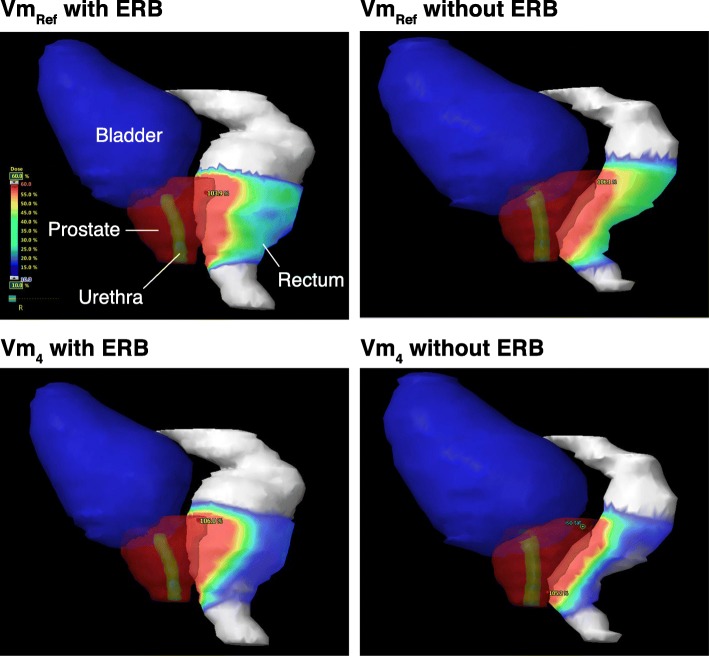

Figure 1 displays the dose distribution in a lateral projection of a reconstructed PTV, bladder and rectum, with and without ERB, in non-optimized and optimized treatment plans (Vmref and Vm4), respectively. It illustrates that the low-to-intermediate dose to the Rwall (3.3–21.8 Gy, i.e. 10–60% of the prescription dose 36.25 Gy) was strongly reduced using the plan optimization strategy in a similar way with and without ERB.

Fig. 1.

Three-dimensional representation of the PTV, uPRV, bladder, and rectum for the same patient with a colorwash display of the dose (from 10 to 60%) comparing plans Vmref vs. Vm4 with and without ERB

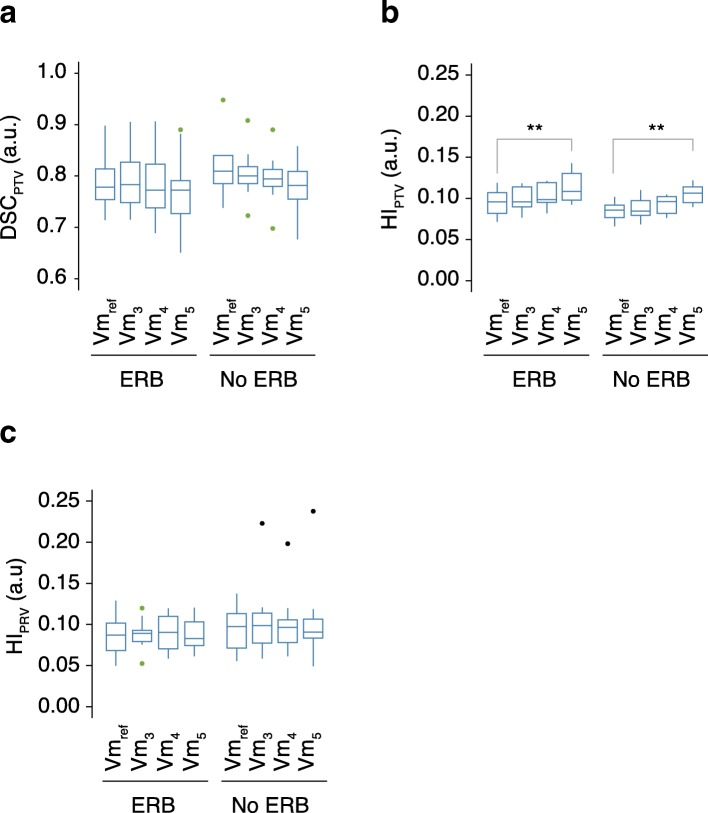

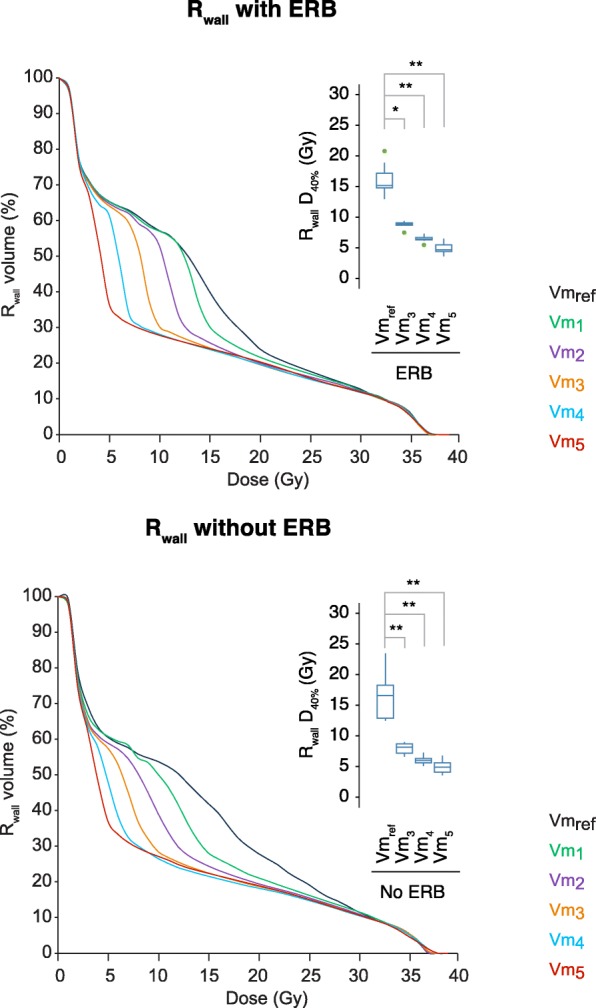

Figure 2 shows the Rwall dose-volume histogram (DVH), with a focus on D40%, for plans from Vmref to Vm5 with and without ERB. The optimization strategy achieves a significant decrease of low-to-intermediate dose to the Rwall. Step Vm4 halved D30%, D40%, D50%, and Dmed and decreased by a third D60% compared to Vmref (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Dosimetric parameters for Rwall. Median DVH from Vmref to Vm5 with ERB and without ERB. Box-and-whisker plots for Vmref, Vm3, Vm4, and Vm5 of D40%. Significant relations are shown with gray lines above the boxplots. * is set for P < 0.05 and ** for P < 0.005. Outliers are visible with green dots for out-values (1.5xIQR)

Table 2.

Dosimetric data for PTV, uPRV and OAR with and without ERB. Comparison between the treatment plans Vmref and Vm4

| ERB | No ERB | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vmref | Vm4 | P-value | Vmref | Vm4 | P-value | |

| PTV | ||||||

| HI (u.a.) | 0.096 [0.071–0.119] | 0.099 [0.082–0.121] | 0.721 | 0.086 [0.066–0.102] | 0.096 [0.076–0.105] | 0.156 |

| DSC (u.a.) | 0.779 [0.714–0.898] | 0.773 [0.689–0.906] | 1 | 0.810 [0.738–0.948] | 0.795 [0.698–0.89] | 1 |

| D2% (Gy) | 38.0 [37–38.9] | 38.1 [37.4–39] | 0.433 | 37.6 [36.8–38.2] | 38.0 [37.2–38.3] | 0.276 |

| uPRV | ||||||

| HI (u.a.) | 0.088 [0.051–0.13] | 0.092 [0.06–0.121] | 1 | 0.099 [0.057–0.139] | 0.098 [0.063–0.199] | 1 |

| Rwall | ||||||

| D10% (Gy) | 32.6 [29.9–35.8] | 32.4 [25.6–35.7] | 0.229 | 31.8 [29.9–35.6] | 30.9 [26.7–35.3] | 0.172 |

| D20% (Gy) | 23.1 [18.2–28.8] | 19.8 [10.7–27.6] | < 0.001 | 24.7 [19.2–29.5] | 19.2 [14.4–28.5] | < 0.001 |

| D30% (Gy) | 17.9 [15–22.9] | 8.5 [6.2–13.1] | < 0.001 | 19.6 [14.5–24.9] | 8.3 [6.1–13.7] | < 0.001 |

| D40% (Gy) | 15.2 [13–20.8] | 6.5 [5.5–7.3] | < 0.001 | 16.6 [12.5–23.5] | 6.0 [5.1–7.3] | < 0.001 |

| D50% (Gy) | 12.9 [4.2–19.6] | 6.0 [3.3–6.8] | < 0.001 | 12.8 [6.3–22.2] | 5.0 [4.1–6.5] | < 0.001 |

| D60% (Gy) | 9.1 [2.5–18.2] | 5.4 [2.2–6.4] | < 0.001 | 6.1 [2.4–19.7] | 4.1 [2.2–5.8] | 0.041 |

| Dmed (Gy) | 12.9 [4.1–19.5] | 5.9 [3.3–6.7] | < 0.001 | 12.2 [6.3–22.1] | 4.9 [4–6.5] | < 0.001 |

| Bwall | ||||||

| V18.1 Gy (%) | 32.6 [15.6–47.5] | 28.5 [13.3–45.5] | 0.010 | 26.0 [14.9–44.8] | 23.2 [13.1–41.8] | 0.036 |

| Fheads | ||||||

| D2% | 10.6 [9–14.1] | 16.3 [13.7–17.8] | < 0.001 | 11 [8.3–12.6] | 13.3 [10.7–16.5] | 0.141 |

| MU | 2110 [1788–2478] | 2897 [2515–3168] | < 0.001 | 2256 [1834–2897] | 2763 [2419–3161] | 0.002 |

The extreme optimization objectives on the Rwall worsen the target homogeneity index HIPTV (p-value < 0.01) in a similar way with and without ERB in Vm5, because of a higher D2% (p < 0.01): 38.5 Gy vs 38.0Gy with ERB; 38.4Gy vs 37.6Gy without ERB. Both the DSC and the HIuPRV remained stable (Fig. 3). No differences were observed in terms of DSC, HIPTV, and HIuPRV, when comparing paired plans with and without ERB.

Fig. 3.

Box-and-whisker plots of (A) DSCPTV, (B) HIPTV and (C) HIuPRV with ERB and without ERB for Vmref, Vm3, Vm4, and Vm5. Outliers are visible with green dots for out-values (1.5xIQR) and black dots for extreme out-values (3xIQR). Significant relations are shown with gray lines above the boxplots. * is set for P < 0.05 and ** for P < 0.005

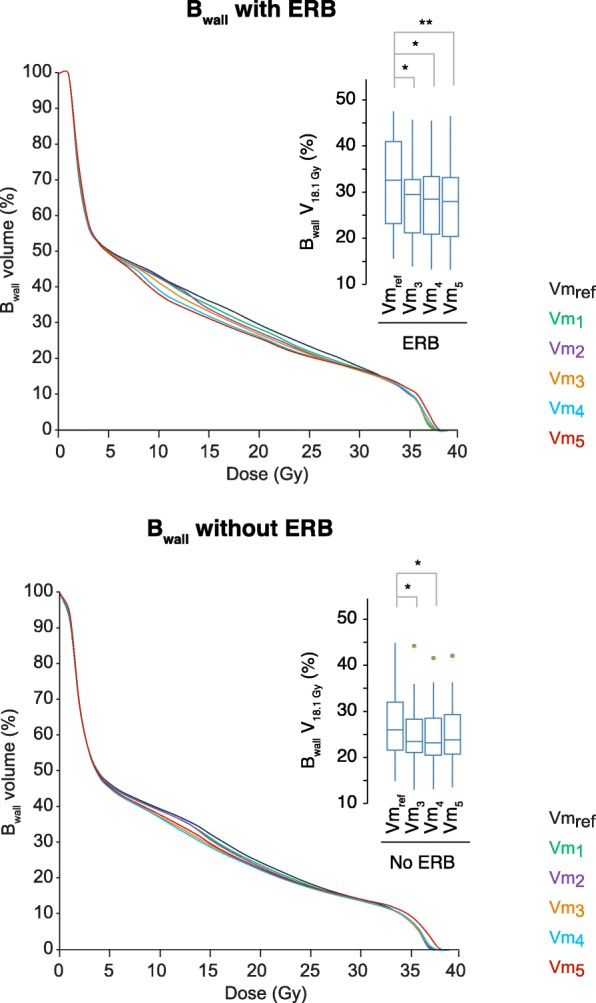

Figure 4 shows the Bwall DVH, with a focus on the V18.1 Gy, for plans from Vmref to Vm5 with and without ERB. The successive optimizations on Rwall slightly lowered V18.1 Gy (p < 0.036) with and without ERB. A higher D2% for Fheads is observed for plans with ERB (p < 0.01) (Table 2). No statistical differences in MU were observed for paired plans with and without ERB, MU increasing similarly with optimization. The fourth optimization Vm4 is found to be the best compromise between the Rwall sparing, PTV and uPRV homogeneity and dose coverage, and other OAR irradiation with and without ERB.

Fig. 4.

Dosimetric parameters for Bwall. Median DVH from Vmref to Vm5 with ERB and without ERB. Box-and-whisker plots for Vmref, Vm3, Vm4, and Vm5 of V18.1 Gy. Significant relations are shown with gray lines above the boxplots. * is set for P < 0.05 and ** for P < 0.005. Outliers are visible with green dots for out-values (1.5xIQR)

Discussion

In this study, the potential for decreasing low and intermediate doses to the Rwall by pushing down the dose constraints to the Rwall in sequential plan optimization steps was investigated with and without ERB. Starting with individually optimized plans, the Rwall sparing could be improved in four optimization steps (Vm4) without impairing the PTV or uPRV coverage, although at the expense of more MU and slightly higher dose to the Fheads. The delivery of more MU and its impact on the beam-on time could be solved by using flattening filter free beams (high dose-rate) that can reduce treatment delivery time. Three additional dose-constraints to the Rwall (Table 1), corresponding to the 90th percentile of the distribution of D30%, D40%, and Dmed in Vm4 plans, can be proposed to improve the Rwall sparing in prostate SBRT as a consequence of this study: V7.2Gy < 40%, V13.1 Gy < 30%, and Dmed < 6.5 Gy. This work was carried out for an SBRT dose prescription but a similar Rwall sparing could be achieved in conventionally fractionated prostate treatments.

By pushing down the Rwall DVO constraints to the limit (i.e. until the TPS is unable to optimize without impairing the PTV coverage) we observed that treatment plans with and without ERB gave similar results in the low-to-intermediate dose range. Patel et al. showed a dose reduction to the Rwall from using an ERB with 3-dimensional conformal RT (3DCRT) but not with intensity modulated RT (IMRT) [16]. Van Lin et al. reported similar results with the reduction of the Rwall mean dose, V50Gy, and V70Gy, with 3DCRT but not with IMRT [17]. However, Smeenk et al. found that the dose to the anorectal region was improved with an ERB, including for IMRT [18]. Two recent studies analyzed the effect of using an ERB for prostate SBRT in the range of intermediate to high doses. A linac-based study [19] found that the presence of the ERB increased the volume of the Rwall receiving high doses (V95% and V99%) whereas no statistical difference was observed at an intermediate dose level (V50%). A Cyberknife-based study [20] observed that V50%, V80%, V90% and V100% were lower with an ERB.

In light of the findings of this study, it may be important for modulated delivery techniques to evaluate the dosimetric impact for the Rwall of the use of an ERB separately from the optimization process, which has an important influence on the dose to the OAR. Different optimization approaches may explain the conflicting results obtained in the studies above.

Avoiding the overlap of a target and an OAR in a beam projection is of critical importance for sparing healthy tissues with 3DCRT plans and direct planning software. With inverse planning techniques, convex isodoses and steep dose gradients reduce the importance of the proximity of targets and OAR for dose reduction. As reported by Kim et al., severe late rectal toxicity may be mostly correlated with the absolute volume of Rwall receiving high doses (>3cm3), but also with the circumference of Rwall receiving 39 Gy in 5 fractions (V39Gy > 35%). Grade 2 acute rectal toxicity has been correlated with the circumference of Rwall receiving 24Gy in 5 fractions (V24Gy > 50%) [7]. A recent study [8] showed that patients treated with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-based prostate delineation or an endorectal balloon (ERB) had favorable anorectal dose distributions (range of 5–60 Gy in 39 or 19 fractions) and favorable toxicity profiles. Van Lin et al. [21] had already observed less telangiectasia for patients with smaller volumes of Rwall exposed to doses >40Gy, corresponding to the group of patients with an ERB in their 3DCRT study. Based on these observations, it seems prudent to lower the intermediate doses to the Rwall by pushing down the DVO constraints on the Rwall regardless of the use or not of an ERB. To further decrease the highest doses received by the Rwall, while maintaining optimal target coverage, only the use of reabsorbable gel-spacers implanted between the anterior Rwall and the posterior aspect of the prostate gland before SBRT may help [12, 22, 23].

The number of patients selected for this dosimetric study, although small, was consistent with the previous studies for 3DCRT, IMRT and SBRT. Because the patients had repeated CT scans with and without ERB, a rigorous controlled comparison could be made. This is an important advantage compared to previous studies because an inflated ERB can modify the shape of the adjacent organs. The optimization strategy of reducing the dose to an organ, such as the Rwall, in a stepwise manner while keeping the other constraints constant is comparable to a Pareto optimal front technique [24]. The preparation, by a single planner, of many plans per patient, is time-consuming and can potentially introduce planning bias [25]. Our methodology can be used as an alternative for centers that are not equipped with Pareto-surface based multicriteria optimization (MCO) planning software [26]. The interest of this kind of software is that it is fast and can contribute to removing manual planning bias.

Conclusions

In conclusion, further optimization of the dose to the Rwall, beyond the usual recommendations for SBRT of prostate cancer, was feasible without compromising dose homogeneity to the target (i.e., the PTV and the uPRV) with and without an ERB. Nonetheless, a larger amount of MU were required for the fully optimized plans. The main outcome of this work was to establish that one optimal technique for reducing the low- to- intermediate dose to the Rwall was a step wise optimization approach. Despite the inherent limitations of our study, we were unable to demonstrate that the use of an ERB allows additional low-to-intermediate dose reduction to Rwall.

Acknowledgements

This study and the Novalis Circle SBRT Prostate Cancer Phase-II Trial, were supported by “Fundació Privada CELLEX” and by BrainLAB.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- 3DCRT

3-dimensional conformal RT

- Bwall

bladder wall

- CTsim

computed tomography simulation scan

- Dmed

median dose

- DSC

Dice similarity coefficient

- DVH

dose-volume histogram

- DVO

dose-volume optimization

- Dxx%

dose received by xx% of a volume

- EQD2

equivalent dose in 2 Gy per fraction

- ERB

endorectal balloon

- Fheads

femoral heads

- HIPTV

homogeneity index for PTV

- HIuPRV

homogeneity index for uPRV

- IMRT

intensity modulated RT

- MCO

multicriteria optimization

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- MU

monitor units

- OAR

organ at risk

- PTV

planning treatment volume

- Rwall

rectal wall

- SBRT

stereotactic body radiotherapy

- TPS

treatment planning system

- uPRV

urethral planning risk volume

- Vm1 to Vm5

optimized plans in 5 sequential steps

- VMAT

volumetric modulated arcs

- Vmref

reference plans

- Vxx%

volume encompassed by the xx% isodose line

Authors’ contributions

AD, MR, TZ and RM designed the study and wrote the manuscript. MR created the dosimetric plans and collected the data. AD and TZ performed the statistical modeling and analyzed the data. LT, WV, MB, NL, JL, JP, ZO and LE helped with writing the manuscript. RM supervised the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This is a dosimetric sub-study from a prospective multicentric randomized phase-II trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT01764646). The trial obtained the ethics approval from Geneva Univeristy Hospital Protocole 11–196 (NAC 11–089).

Consent for publication

We obtained written informed consent to publish from patients.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Angèle Dubouloz, Phone: +41 22 37 27 090, Email: angele.dubouloz@hcuge.ch.

Michel Rouzaud, Email: michel.rouzaud@hcuge.ch.

Lev Tsvang, Email: lev.tsvang@sheba.health.gov.il.

Wilko Verbakel, Email: w.verbakel@vumc.nl.

Mikko Björkqvist, Email: mikko.bjorkqvist@tyks.fi.

Nadine Linthout, Email: nadine.linthout@olvz-aalst.be.

Joana Lencart, Email: joana.lencart@ipoporto.min-saude.pt.

Juan María Pérez-Moreno, Email: jmperez@hmhospitales.com.

Zeynep Ozen, Email: zeynepozen68@yahoo.com.

Lluís Escude, Email: lluis.escude@gmx.net.

Thomas Zilli, Email: thomas.zilli@hcuge.ch.

Raymond Miralbell, Email: raymond.miralbell@hcuge.ch.

References

- 1.King CR, Brooks JD, Gill H, et al. Long-term outcomes from a prospective trial of stereotactic body radiotherapy for low-risk prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82:877–882. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.11.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miralbell R, Roberts SA, Zubizarreta E, et al. Dose-fractionation sensitivity of prostate cancer deduced from radiotherapy outcomes of 5,969 patients in seven international institutional datasets: alpha/beta = 1.4 (0.9-2.2) Gy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82:e17–e24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.10.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fowler J, Chappell R. Ritter M. Is alpha/beta for prostate tumors really low? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;50:1021–1031. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(01)01607-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimizu S, Nishioka K, Suzuki R, et al. Early results of urethral dose reduction and small safety margin in intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) for localized prostate cancer using a real-time tumor-tracking radiotherapy (RTRT) system. Radiat Oncol. 2014;9:118. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-9-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen LN, Suy S, Uhm S, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) for clinically localized prostate cancer: the Georgetown University experience. Radiat Oncol. 2013;8:58. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-8-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vainshtein J, Abu-Isa E, Olson KB, et al. Randomized phase II trial of urethral sparing intensity modulated radiation therapy in low-risk prostate cancer: implications for focal therapy. Radiat Oncol. 2012;7:82. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-7-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim DW, Cho LC, Straka C, et al. Predictors of rectal tolerance observed in a dose-escalated phase 1-2 trial of stereotactic body radiation therapy for prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;89:509–517. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wortel RC, Heemsbergen WD, Smeenk RJ, et al. Local protocol variations for image-guided radiotherapy in the multicenter Dutch hypofractionation (HYPRO) trial: impact of rectal balloon and MRI delineation on anorectal dose and gastrointestinal toxicity levels. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics. 2017; [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Wolff D, Stieler F, Welzel G, et al. Volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT) vs. serial tomotherapy, step-and-shoot IMRT and 3D-conformal RT for treatment of prostate cancer. Radiotherapy and oncology : journal of the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology. 2009;93:226–233. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smeenk RJ, Teh BS, Butler EB, et al. is there a role for endorectal balloons in prostate radiotherapy? A systematic review. Radiotherapy and oncology : journal of the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology. 2010;95:277–282. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Chapet O, Udrescu C, Devonec M, et al. Prostate hypofractionated radiation therapy: injection of hyaluronic acid to better preserve the rectal wall. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;86:72–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weber DC, Zilli T, Vallee JP, et al. Intensity modulated proton and photon therapy for early prostate cancer with or without transperineal injection of a polyethylen glycol spacer: a treatment planning comparison study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;84:e311–e318. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isacsson U, Nilsson K, Asplund S, et al. A method to separate the rectum from the prostate during proton beam radiotherapy of prostate cancer patients. Acta Oncol. 2010;49:500–505. doi: 10.3109/02841861003745535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smeenk RJ, Louwe RJ, Langen KM, et al. An endorectal balloon reduces intrafraction prostate motion during radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83:661–669. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gay HA, Barthold HJ, O'Meara E, et al. Pelvic normal tissue contouring guidelines for radiation therapy: a radiation therapy oncology group consensus panel atlas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83:e353–e362. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patel RR, Orton N, Tome WA, et al. Rectal dose sparing with a balloon catheter and ultrasound localization in conformal radiation therapy for prostate cancer. Radiotherapy and oncology : journal of the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology. 2003;67:285–294. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8140(03)00056-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Lin EN, Hoffmann AL, van Kollenburg P, et al. Rectal wall sparing effect of three different endorectal balloons in 3D conformal and IMRT prostate radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63:565–576. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smeenk RJ, van Lin EN, van Kollenburg P, et al. Anal wall sparing effect of an endorectal balloon in 3D conformal and intensity-modulated prostate radiotherapy. Radiotherapy and oncology : journal of the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology. 2009;93:131–136. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong AT, Schreiber D, Agarwal M, et al. Impact of the use of an endorectal balloon on rectal dosimetry during stereotactic body radiation therapy for localized prostate cancer. Practical radiation oncology. 2015 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Xiang HF, Lu HM, Efstathiou JA, et al. Dosimetric impacts of endorectal balloon in CyberKnife stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) for early-stage prostate cancer. Journal of applied clinical medical physics. 2017;18:37–43. doi: 10.1002/acm2.12063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Lin EN, Kristinsson J, Philippens ME, et al. Reduced late rectal mucosal changes after prostate three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy with endorectal balloon as observed in repeated endoscopy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;67:799–811. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chapet O, Udrescu C, Tanguy R, et al. Dosimetric implications of an injection of hyaluronic acid for preserving the Rectal Wall in prostate stereotactic body radiation therapy. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics. 2014;88:425–432. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruggieri R, Naccarato S, Stavrev P, et al. Volumetric-modulated arc stereotactic body radiotherapy for prostate cancer: dosimetric impact of an increased near-maximum target dose and of a rectal spacer. Br J Radiol. 2015;88:20140736. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20140736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lechner W, Kragl G, Georg D. Evaluation of treatment plan quality of IMRT and VMAT with and without flattening filter using Pareto optimal fronts. Radiotherapy and oncology : journal of the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology. 2013;109:437–441. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2013.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marino C, Villaggi E, Maggi G, et al. A feasibility dosimetric study on prostate cancer : are we ready for a multicenter clinical trial on SBRT? Strahlentherapie und Onkologie : Organ der Deutschen Rontgengesellschaft [et al] 2015;191:573–581. doi: 10.1007/s00066-015-0822-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Craft DL, Hong TS, Shih HA, et al. Improved planning time and plan quality through multicriteria optimization for intensity-modulated radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82:e83–e90. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.