Abstract

Short episodes of ischemia can protect neuronal cells and tissue against a subsequent lethal ischemia by a phenomenon called ischemic preconditioning. The development of this tolerance depends on protein synthesis and takes at least 1 day. It therefore seems reasonable that preconditioning leads to upregulation and translation of protective genes or posttranslational modification of pro- or antiapoptotic proteins. We recently used suppression subtractive hybridization to identify transcripts upregulated in rat primary neuronal cultures preconditioned by oxygen glucose deprivation. In this contribution, we describe the previously unknown 7-kb full-length sequence of an upregulated expressed sequence tag and show that it constitutes the 3′ end of the large untranslated region of the noncatalytic “truncated” growth factor receptor TrkB.T1. TrkB.T1 is expressed most prominently in the adult brain and its mRNA was found to be 2.1-fold upregulated by ischemic preconditioning. At the protein level, however, TrkB.T1 was clearly downregulated, possibly by increased degradation in preconditioned cultures. TrKB.T1 can act as a dominant-negative inhibitor of its catalytic counterpart TrkB, which is the receptor for brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a factor induced by ischemia that can protect from ischemia-induced neuron loss. We hypothesize that the downregulation of TrkB.T1 at the protein level can prolong BDNF-mediated protective signaling via the catalytic receptor and thus participates in the development of ischemic preconditioning.

Key words: Ischemic preconditioning, Oxygen-glucose deprivation, SMART cDNA synthesis, Subtractive suppression hybridization, TrkB.T1

SHORT episodes of ischemia followed by reperfusion protect mammalian cells and tissue against a subsequent lethal ischemia and reperfusion. This phenomenon is called ischemic preconditioning (IP) and was reported first for the heart, where a series of short coronary artery occlusions followed by reperfusion protected the myocardium from a subsequent lethal ischemia (30). Even the brain can be protected by IP from an otherwise lethal ischemia. This was shown in vivo (23,24,27) and in vitro. In vitro, ischemia can be mimicked by depriving organotypic brain slices (1,16,31) or primary neuronal cultures (8,9,22,38) from oxygen and glucose over a defined period. Reperfusion is simulated by subsequent exposure to normally oxygenized cell culture medium. The mediators implicated in IP so far have been identified by a candidate approach and include adenosine and the A1-adenosine receptor (31), ATP-sensitive K+ channels (19), protein kinase C (18), nitric oxide (7), mitogen-activated kinase (20), and heat shock proteins (27).

As the development of tolerance is dependent on protein synthesis (3), it seems reasonable to speculate that preconditioning of neuronal cells leads to upregulation and translation of protective genes. Therefore, the transcriptional analysis of preconditioned cells could lead to the identification of novel neuroprotective genes. We recently subtracted the mRNA content of preconditioned and control rat primary neuronal cultures by subtractive suppression analysis and deposited the sequences of upregulated transcripts online.

In this contribution, we show that one expressed sequence tag with a significant regulation in the used screening procedure corresponds to the 3′ untranslated region of the noncatalytic growth factor receptor TrkB.T1. We cloned and sequenced the hitherto unknown full-length transcript and investigated its regulation in preconditioned and control cultures at mRNA and protein levels.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Full-Length Cloning of BU198076

To elucidate the identity of the sequence tag BU198076 we used the wealth of data available for human expressed sequence tags. The human orthologue was obtained by blasting BU198076 against the human EST subset of dbEST. Assembling all available overlapping ESTs with SEQMAN (DnaStar, Madison, WI) resulted in an in silico sequence bearing high homology to the growth factor receptor TrkB.T1 at its 5′ end. We designed a forward primer in the TrkB receptor sequence common to all isoforms and performed a long-distance PCR using human retinoic acid-induced NT2 cell cDNA as template (26) and the PfuTurbo Hotstart DNA Polymerase system (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Cycle parameters were 95°C for 2 min, 57°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 4 min (+ 5 s from cycle 10 to 30). The expected 5.2-kb fragment was excised, purified, digested with EcoRI, ligated into pSK+, sequenced, and submitted to Genbank (Accession AF508964).

Preparation of Rat Primary Cortical Cultures

To investigate the regulation in preconditioned and control cultures, we prepared cortical neurons from whole cerebral cortices of fetal Wistar rats (E16–18) as described previously (9). After removing the meninges the tissue was minced and digested with trypsin (0.005%; 0.002% EDTA; 15 min, 37°C) followed by mechanical dissociation. Cells (2 × 106) were seeded in 35-mm culture dishes coated with 10 μg ml poly-l-lysine (Biochrom, Germany) and 10 μg/ml collagen G (Biochrom) in plating medium consisting of Neurobasal™ medium with B-27 serum-free supplement (Gibco, Germany), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 25 μM glutamate, and 2 mM l-glutamine. After 4 days in vitro (DIV), medium was changed to supplemented Neurobasal™ medium without glutamate.

Ischemic Preconditioning and Viability Assay

For ischemic preconditioning, DIV8 rat cortical cultures were supplemented with 2% fetal calf serum (FCS) and left in the incubator for another 24 h before two washes with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and subsequent exposure to deoxygenated OGD buffer containing NaCl (115 mM), KCl (5.4 mM), MgSO4 (0.8 mM), CaCl (1.8 mM), HEPES-NaOH (20 mM), 2-deoxy-d-glucose (20 mM), and 2% FCS. Cultures were placed in an airtight plastic chamber, flooded with argon (25), and kept at 37°C for the mentioned time. Control sister cultures were treated with buffered saline solution (BSS, same buffer as mentioned above containing 15 mM d-glucose instead of 2-deoxy-d-glucose) and were placed in a CO2 incubator for the corresponding times. After OGD or BSS, cultures were washed twice with PBS and the conditioned medium stored during the experiment reconstituted. For ischemic preconditioning experiments, DIV9 cultures treated with 60-min OGD or BSS were kept for 24 h in the CO2 incubator and then subjected to 120-min OGD or BSS. Viability was assessed 24 h after the second OGD by the amount of blue formazan produced by viable cells from the tetrazolium salt 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT, Sigma), which is proportional to the number of cells (29). Briefly, MTT was diluted in PBS, added to the culture media in a final concentration of 1 mg/ml, and incubated at 37°C. After 2 h cells were lysed for 24 h with a buffer containing 50% DMF, 20% SDS, 2.5% acetic acid, and 2.5% 1 M HCl (pH 4.7). Finally, 100 μl medium was removed and the formation of formazan monitored by reading the optical density at 550 nm using a microplate reader.

Real-Time Quantitative RT-PCR

Ten sister cultures containing approximately 2 × 107 cells from a successful experiment defined as a significant difference in viability between preconditioned and not-preconditioned cultures (p < 0.001) were used for mRNA and protein preparation with the TRIzol™ reagent 24 h after OGD or BSS treatment. Poly (A)+ RNA was isolated by DynaBead purification (Dynal Biotech GmbH, Hamburg, Germany) and single-stranded cDNA synthesized using the SMART™ (Switching Mechanism At 5′ end of RNA Template) PCR cDNA synthesis kit (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA). Virtual Northern blots were performed as described in the SMART PCR cDNA synthesis system (Clontech). Briefly, first-strand cDNA synthesis includes incorporation of the SMART II A oligonucleotide at the 5′ end of all cDNA species. This 5′ oligonucleotide functions as primer binding site and together with the corresponding site on the 3′ oligo(dT) cDNA synthesis primer allows PCR amplification of cDNAs if starting material is limited. The PCR product was separated by gel electrophoresis and transferred to a nylon membrane. Specific probes were generated by radioactive linear PCR using primer np1 for 30 cycles (conditions were: 94°C for 2 min, 68°C for 2 min, and 72°C for 5 min). Unamplified cDNA and the Mouse Multiple Tissue cDNA panel (MTC™ , Clontech) served as template in real-time PCR performed on a ABI PRISM 7900HT real-time PCR cycler (Applied Biosystems) using the qPCR™ Core Kit for Sybr™ Green I (Eurogentec) according to the manual. PCR was done in triplicate with primers and conditions as given in Table 1. Primers used with the cDNA panel are based on a mouse sequence tag located downstream of the TrkB open reading frame (Image clone ID 30622250) showing 88% identity with BU198076 (BLAST p-value 5.1e-157). A standard dilution series of TrkB.T1 vector DNA was supplied as template to calculate amplification efficiencies, perform absolute quantification, and test for differences in efficiency between 96-well plates. All runs were analyzed using the SDS 2.1 software (Applied Biosystems). Baseline and threshold were optimized empirically. PCR efficiency was calculated using the slope of the regression curve fitted to the standard dilution CT values. Relative regulation x normalized to mean housekeeping gene regulation was calculated using

with E amplification efficiency, ΔCT difference of CT values between two different samples. Mean and standard error were calculated using Prism software (Graphpad).

TABLE 1.

SEQUENCE AND CYCLE PARAMETERS OF OLIGONUCLEOTIDES

| Name | Forward Primer 5′-3′ | Reverse Primer 5′-3′ | T anneal | Cycles |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GADPH | ACCACAGTCCATGCCATCAG | TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTA | 65°C | 18–33 |

| β-Actin | CGGGACCTGACAGACTACCTCA | GGCCATCTCTTGCTCGAAG | 61°C | 18–24 |

| Rat | GGGTCCAAATCCATCTGCTG | TTGAAAACCCAGAATATTATA | 53°C | 20–25 |

| Mouse | TCCCAAACCCACACTACACC | TCTCCCTCCCAAGAACACTAA | 60°C | 20–30 |

| LD PCR | AAACCGGAATTCCCCTGAAGTCC | TGATGGAATTCCGCAAGTACA | 57°C | 30 |

Northern Blotting

For Northern blots, 10 μg of total RNA from DIV9 rat primary cortical neurons was separated by denaturing 1.2% agarose gel electrophoresis and then was transferred to a nylon membrane. A rat-specific BU198076 probe was generated by linear radioactive PCR as described using 25 ng of a purified colony PCR product as template. Blots were hybridized overnight in UltraHyb (AMS Biotechnology GmbH, Wiesbaden, Germany) solution at 42°C and washed twice under high-stringency conditions. Autoradiography was performed using a phosphoimaging system (Fujix) for various exposure times.

Western Blotting

Proteins for Western blots were precipitated by the addition of three volumes acetone to the TRIzol™-treated cultures used for mRNA preparation and pelleted by centrifugation at 5000 × g for 2 min. The pellet was dispersed by sonication in 100 μl of Tris-HCl (pH 8.5) and the yield of proteins assessed by the Micro BCA Protein Assay Reagent Kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Thirteen and 20 μg of OGD and BSS proteins were separated on a reducing 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to Immobilon-P membranes. TrkB.T1 was detected on the blot using a polyclonal anti-TrkB.T1 antibody in a dilution of 1:200 (C-13, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and a polyclonal affinity purified β-actin (1: 1000, Sigma-Aldrich) antibody. Subsequently, blots were washed in TBS-T and incubated for 1 h with the secondary antibody (anti-rabbit, 1:7000, Promega) conjugated to alkaline phosphatase. After a second wash, labeled proteins were detected using the ECL-reagent (Lumi-Phos WB; Pierce).

RESULTS

BU198076 Corresponds to the Noncatalytic Growth Factor Receptor TrkB.T1

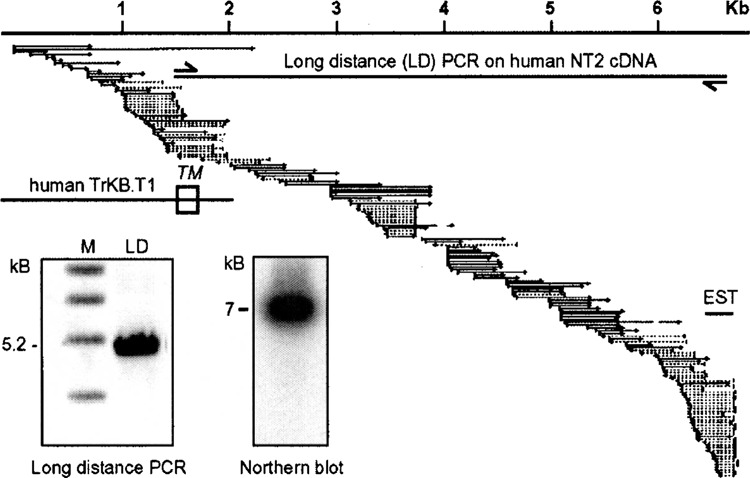

We recently subtracted cDNA from preconditioned and control cultures by subtractive suppression hybridization and identified, among other transcripts, one expressed sequence tag named BU198076. This clone was significantly regulated in an initial screening process consisting of a dot blot and a virtual Northern blot analysis (not shown). Virtual Northern blots contain amplified cDNA and are supposed to correlate with results obtained by traditional Northern blotting (10). We were able to assign the sequence tag to a known gene by a combination of in silico and traditional cloning. The wealth of human ESTs was used to assemble a large virtual transcript starting with the putative human orthologue of BU198076 (Accession #AA779107) identified by cross-species BLASTN. The 5′ end of the 7-kb in silico message was identical with the noncatalytic growth factor receptor TrkB.T1. As 67% of the 136 human sequences used for the assembly came from nervous system tissues, we used cDNA from neuronally differentiated human NT2 cells in a long-distance PCR with a forward primer situated in the extracellular domain of the human TrkB gene common to all isoforms and the reverse primer in the identified EST orthologue. This yielded a single product of the predicted size (Fig. 1, left inset), which was cloned, sequenced, and deposited under the Genbank accession number AF508964. It encoded a splice isoform of the growth factor receptor TrkB named TrkB.T1 that lacks tyrosine kinase activity. The large 3′ untranslated region was found to be very AT rich. Within this region, we recognized an element with two ATTTA pentamers and an ATTTTTA extended pentamer within 66 nucleotides. Blasting the human sequence against rat genomic sequence resulted in only one significant hit (BLAST p-value 1e-84) on rat chromosome 17 downstream of the rat TrkB receptor coding region, proving that our strategy was successful. Our in silico sequence also corresponded to the size seen in a Northern blot containing RNA from rat primary cultures (Fig. 1, right inset).

Figure 1.

Clone BU198076 is part of the 3′ untranslated region of the noncatalytic growth factor receptor TrkB.T1 The human orthologue of BU198076 was identified by BLAST and assembled with all available human expressed sequence tags. The relative position of human BU198076 (EST), the previously known sequence of TrkB.T1 with its transmembrane domain (TM), and the long-distance PCR primers are indicated. Inserts show a long-distance PCR product using human NT2 cell cDNA and the above primers separated by agarose gel electrophoresis and a Northern blot loaded with 10 μg total RNA from DIV9 rat primary cortical cultures hybridized with labeled rat BU198076. Sizes are indicated. M, marker.

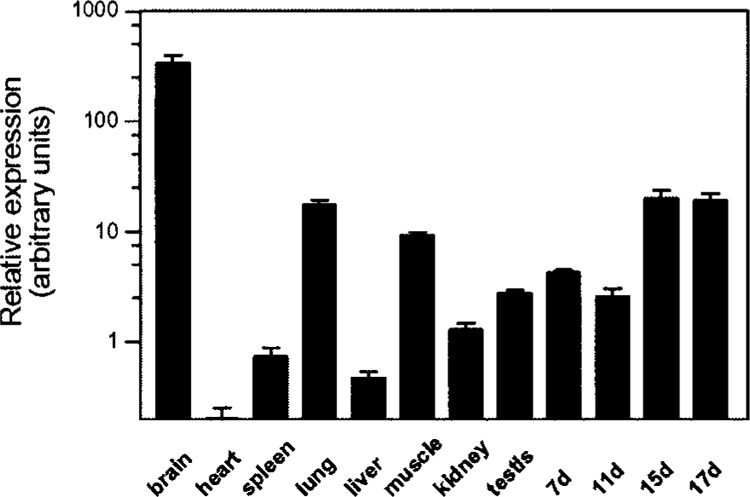

Tissue Distribution of TrkB.T1

The tissue distribution of TrkB.T1 has not been investigated before. We therefore employed a commercial cDNA panel normalized for the expression of 12 different housekeeping genes to investigate its expression pattern by quantitative PCR. TrkB.T1 was most prominently expressed in adult brain followed by lung, skeletal muscle, and late embryonic tissue. Testis, liver, heart, spleen, kidney, and early embryonic tissue, in contrast, only gave weak signals (Fig. 2, note the exponential scale). The major postnatal upregulation in the brain is in concordance with a previous report, where a sensitive ribonuclease-protection assay was used to study the developmental regulation of different TrkB isoforms in the rat forebrain (14), which further proves that BU198076 corresponds to TrkB.T1.

Figure 2.

TrkB.T1 tissue expression as fold regulation over heart expression determined by real-time quantitative PCR. Bar graphs represent mean ± SEM of two experiments done in triplicate. cDNA is normalized to the expression level of 12 different housekeeping genes.

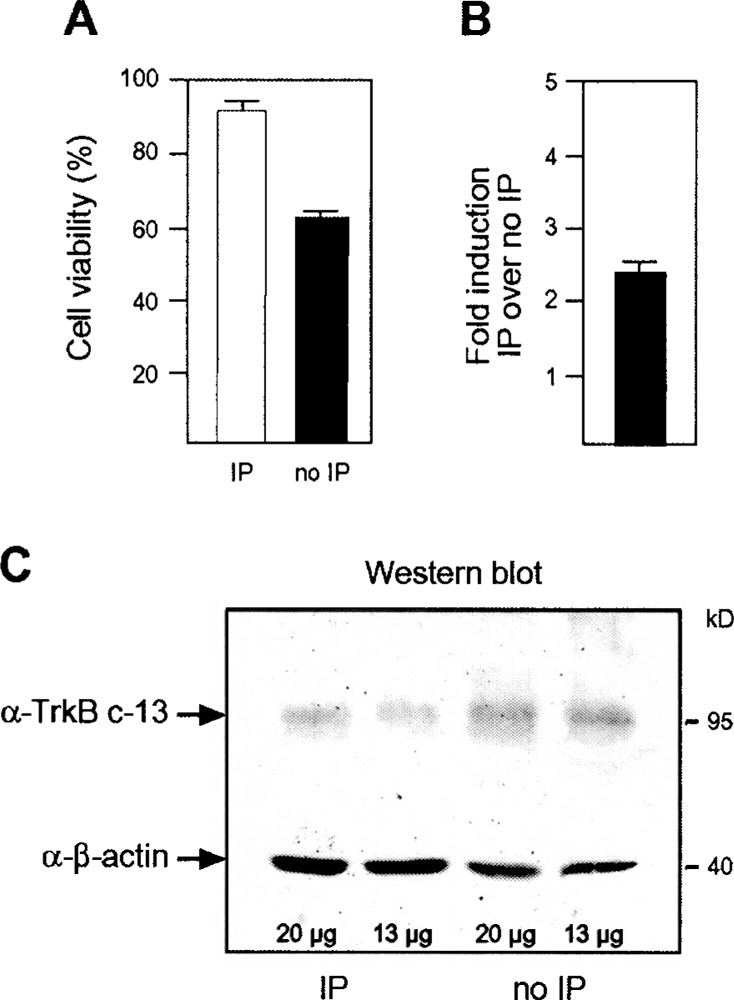

Regulation of TrkB.T1 by Ischemic Preconditioning of Rat Cortical Cultures

Rat primary cortical cultures DIV9 were subjected to 60-min oxygen glucose deprivation (OGD) or control treatment with buffered saline solution. OGD treatment led to a minimal decrease in cell survival, but did not evoke changes in cell morphology, as judged by phase contrast microscopy (not shown). Sister cultures of those used for cDNA synthesis and protein preparation were again subjected to 120-min OGD the next day, which led to a significant increase in viability only in those treated with OGD. Preconditioned cultures significantly (Student’s t-test, p < 0.001, n = 3 done in quadruplicate) better survived the second OGD by 32% (Fig. 3A). Unamplified cDNA prepared from preconditioned and not-preconditioned cultures was used as template in real-time quantitative PCR; TrkB.T1 was only upregulated 2.1-fold (SEM = 0.262, n = 3 in triplicates) in cDNA derived from preconditioned cultures, which was in contrast to a more prominent regulation observed in the initial virtual Northern blot. This difference was caused by an inefficiency of the SMART amplification reaction for longer cDNA species (not shown), which has not been noticed previously (10,34).

Figure 3.

Cell death caused by oxygen glucose deprivation and protection by ischemic preconditioning. (A) Rat cortical cultures at DIV9 were subjected to 60-min oxygen glucose deprivation (IP) or buffered saline solution (no IP) and 120-min OGD after 24 h. Viability was assessed 24 h thereafter by MTT assay. Graphs represent pooled data of three independent experiments each done in quadruplicate. Viability is shown as mean ± SEM. (B) Real-time PCR results generated from unamplified cDNAs. Bar graphs represent mean ± SEM of three experiments done in triplicate. Induction was normalized to the expression level of β-actin and GADPH. (C) Western blot containing the indicated amount of protein from preconditioned and control rat primary cultures DIV9 and stained simultaneously with antibodies directed against β-actin and TrkB.T1.

To validate these results at the protein level, we used a specific antibody generated against the intra-cellular part that differentiates TrkB.T1 from other TrkB variants. The antibody labeled a singular band of the correct size of 95 kDa in lysates from rat primary cultures subjected to 1 h OGD or BSS. Results were reproduced from three independent samples. TrkB.T1 immunoreactivity was more prominent in BSS-treated cultures, especially when compared with the simultaneously stained control β-actin (Fig. 3C). Therefore, TrkB.T1 was downregulated at the protein level in preconditioned cultures probably due to increased degradation of the protein in preconditioned cells or other posttranslational mechanisms.

DISCUSSION

In this contribution, we focused on a previously identified expressed sequence tag upregulated by ischemic preconditioning of rat primary cultures. We used data from the human genome project to clone the corresponding full-length gene and show that this tag is part of the large 3′ untranslated region of the noncatalytic growth factor receptor TrkB.T1. We found an AU-rich element in the human and the putative rat 3′ untranslated region with similarity to the EGF receptor, where this element regulates mRNA stability and translation efficiency (2). Recently, the genomic organization of three TrkB isoforms (35) was reported. The authors used a combination of RT-PCR and Northern blot analyses, but did not describe the full-length sequence presented here.

It is conceivable that the above-mentioned elements allow a posttranscriptional regulation of protein synthesis, explaining the observed downregulation at the protein level. However, the apparent contradictory results from the transcriptional and translational analysis underscore the importance of validating mRNA results at the protein level. It appears that the increased mRNA is counteracted by posttranslational mechanisms initiated by ischemic preconditioning, as this mechanism seems to be abrogated in not-protective paradigms of neuronal injury. TrkB.T1 was found by immunohistochemistry to be upregulated in astrocytes surrounding the area of an ischemic infarction 12 and 24 h after MCA occlusion in rats (12). TrkB.T1 is similarly upregulated in models of mechanical spinal cord injury (13,36), in the hippocampus after lesions of the major afferent pathways (4), and after neurotoxic injury (6).

It is commonly believed that the noncatalytic receptor TrkB.T1 acts as dominant-negative inhibitor of protective BDNF signaling through the catalytic TrkB receptor (15,17). BDNF is increased by ischemia (28) and it was shown repeatedly that infusion of BDNF into the brain during and after ischemia reduces ischemia-induced neuron loss (5,11,21,33,37). Also, introduction of TrkB.T1 into neuronal PC12 cells that express the catalytic TrkB isoform inhibits BDNF signaling (17), and transgenic mice overexpressing TrkB.T1 in postnatal neurons show an increased vulnerability to ischemia compared with wild-type littermates (32).

We therefore hypothesize that the downregulation of TrkB.T1 at the protein level can increase the amount of BDNF available to elicit protective signaling via the catalytic TrkB receptor and thus participates in the development of ischemic preconditioning. We hope that the identification of the 3′ end will foster further research into TrkB.T1 regulation by facilitating differential gene expression studies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are most grateful for the continued support and laboratory space provided by Prof. Dr. H. C. Schaller. Julius A. Steinbeck was funded by the Werner-Otto-Stiftung für den Medizinischen Fortschritt. We thank Susanne Thomsen for excellent technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1. Badar-Goffer R. S.; Thatcher N. M.; Morris P. G.; Bachelard H. S. Neither moderate hypoxia nor mild hypoglycaemia alone causes any significant increase in cerebral [Ca2+]i: Only a combination of the two insults has this effect. A 31P and 19F NMR study. J. Neurochem. 61:2207–2214; 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Balmer L. A.; Beveridge D. J.; Jazayeri J. A.; Thomson A. M.; Walker C. E.; Leedman P. J. Identification of a novel AU-rich element in the 3′ untranslated region of epidermal growth factor receptor mRNA that is the target for regulated RNA-binding proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:2070–2084; 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barone F. C.; White R. F.; Spera P. A.; Ellison J.; Currie R. W.; Wang X.; Feuerstein G. Z. Ischemic preconditioning and brain tolerance: Temporal histological and functional outcomes, protein synthesis requirement, and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist and early gene expression. Stroke 29:1937–1951; 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Beck K. D.; Lamballe F.; Klein R.; Barbacid M.; Schauwecker P. E.; McNeill T. H.; Finch C. E.; Hefti F.; Day J. R. Induction of noncatalytic TrkB neurotrophin receptors during axonal sprouting in the adult hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 13:4001–4014; 1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Beck T.; Lindholm D.; Castren E.; Wree A. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor protects against ischemic cell damage in rat hippocampus. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 14:689–692; 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Belluardo N.; Salin T.; Dell’Albani P.; Mudo G.; Corsaro M.; Jiang X. H.; Timmusk T.; Condorelli D. F. Neurotoxic injury in rat hippocampus differentially affects multiple trkB and trkC transcripts. Neurosci. Lett. 196:1–4; 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bolli R.; Manchikalapudi S.; Tang X. L.; Takano H.; Qiu Y.; Guo Y.; Zhang Q.; Jadoon A. K. The protective effect of late preconditioning against myocardial stunning in conscious rabbits is mediated by nitric oxide synthase. Evidence that nitric oxide acts both as a trigger and as a mediator of the late phase of ischemic preconditioning. Circ. Res. 81:1094–1107; 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bossenmeyer-Pourie C.; Daval J. L. Prevention from hypoxia-induced apoptosis by pre-conditioning: A mechanistic approach in cultured neurons from fetal rat forebrain. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 58:237–239; 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bruer U.; Weih M. K.; Isaev N. K.; Meisel A.; Ruscher K.; Bergk A.; Trendelenburg G.; Wiegand F.; Victorov I. V.; Dirnagl U. Induction of tolerance in rat cortical neurons: hypoxic preconditioning. FEBS Lett. 414:117–121; 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Endege W. O.; Steinmann K. E.; Boardman L. A.; Thibodeau S. N.; Schlegel R. Representative cDNA libraries and their utility in gene expression profiling. Biotechniques 26:542–548, 550; 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ferrer I.; Ballabriga J.; Marti E.; Perez E.; Alberch J.; Arenas E. BDNF up-regulates TrkB protein and prevents the death of CA1 neurons following transient forebrain ischemia. Brain Pathol. 8:253–261; 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ferrer I.; Krupinski J.; Goutan E.; Marti E.; Ambrosio S.; Arenas E. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor reduces cortical cell death by ischemia after middle cerebral artery occlusion in the rat. Acta Neuropathol. (Berl.) 101:229–238; 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Frisen J.; Verge V. M.; Fried K.; Risling M.; Persson H.; Trotter J.; Hokfelt T.; Lindholm D. Characterization of glial trkB receptors: Differential response to injury in the central and peripheral nervous systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:4971–4975; 1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fryer R. H.; Kaplan D. R.; Feinstein S. C.; Radeke M. J.; Grayson D. R.; Kromer L. F. Developmental and mature expression of full-length and truncated TrkB receptors in the rat forebrain. J. Comp. Neurol. 374:21–40; 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fryer R. H.; Kaplan D. R.; Kromer L. F. Truncated trkB receptors on nonneuronal cells inhibit BDNF-induced neurite outgrowth in vitro. Exp. Neurol. 148:616–627; 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gage A. T.; Stanton P. K. Hypoxia triggers neuroprotective alterations in hippocampal gene expression via a heme-containing sensor. Brain Res. 719:172–178; 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Haapasalo A.; Koponen E.; Hoppe E.; Wong G.; Castren E. Truncated trkB.T1 is dominant negative inhibitor of trkB.TK+-mediated cell survival. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 280:1352–1358; 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hara H.; Onodera H.; Yoshidomi M.; Matsuda Y.; Kogure K. Staurosporine, a novel protein kinase C inhibitor, prevents postischemic neuronal damage in the gerbil and rat. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 10:646–653; 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Heurteaux C.; Bertaina V.; Widmann C.; Lazdunski M. K+ channel openers prevent global ischemia-induced expression of c-fos, c-jun, heat shock protein, and amyloid beta-protein precursor genes and neuronal death in rat hippocampus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:9431–9435; 1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hu B. R.; Wieloch T. Tyrosine phosphorylation and activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase in the rat brain following transient cerebral ischemia. J. Neurochem. 62:1357–1367; 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jiang X.; Zhu D.; Okagaki P.; Lipsky R.; Wu X.; Banaudha K.; Mearow K.; Strauss K. I.; Marini A. M. N-methyl-D-aspartate and TrkB receptor activation in cerebellar granule cells: an in vitro model of preconditioning to stimulate intrinsic survival pathways in neurons. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 993:134–145, 159–160; 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Khaspekov L.; Shamloo M.; Victorov I.; Wieloch T. Sublethal in vitro glucose-oxygen deprivation protects cultured hippocampal neurons against a subsequent severe insult. Neuroreport 9:1273–1276; 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kirino T.; Tsujita Y.; Tamura A. Induced tolerance to ischemia in gerbil hippocampal neurons. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 11:299–307; 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kitagawa K.; Matsumoto M.; Tagaya M.; Hata R.; Ueda H.; Niinobe M.; Handa N.; Fukunaga R.; Kimura K.; Mikoshiba K.; et al. ‘Ischemic tolerance’ phenomenon found in the brain. Brain Res. 528:21–24; 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kusumoto M.; Dux E.; Paschen W.; Hossmann K. A. Susceptibility of hippocampal and cortical neurons to argon-mediated in vitro ischemia. J. Neurochem. 67:1613–1621; 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Leypoldt F.; Lewerenz J.; Methner A. Identification of genes up-regulated by retinoic-acid-induced differentiation of the human neuronal precursor cell line NTERA-2 cl.D1. J. Neurochem. 76:806–814; 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Liu Y.; Kato H.; Nakata N.; Kogure K. Temporal profile of heat shock protein 70 synthesis in ischemic tolerance induced by preconditioning ischemia in rat hippocampus. Neuroscience 56:921–927; 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Matsushima K.; Schmidt-Kastner R.; Hogan M. J.; Hakim A. M. Cortical spreading depression activates trophic factor expression in neurons and astrocytes and protects against subsequent focal brain ischemia. Brain Res. 807:47–60; 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: Application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods 65:55–63; 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Murry C. E.; Jennings R. B.; Reimer K. A. Preconditioning with ischemia: A delay of lethal cell injury in ischemic myocardium. Circulation 74:1124–1136; 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Perez-Pinzon M. A.; Mumford P. L.; Rosenthal M.; Sick T. J. Anoxic preconditioning in hippocampal slices: Role of adenosine. Neuroscience 75:687–694; 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Saarelainen T.; Lukkarinen J. A.; Koponen S.; Grohn O. H.; Jolkkonen J.; Koponen E.; Haapasalo A.; Alhonen L.; Wong G.; Koistinaho J.; Kauppinen R. A.; Castren E. Transgenic mice overexpressing truncated trkB neurotrophin receptors in neurons show increased susceptibility to cortical injury after focal cerebral ischemia. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 16:87–96; 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schabitz W. R.; Schwab S.; Spranger M.; Hacke W. Intraventricular brain-derived neurotrophic factor reduces infarct size after focal cerebral ischemia in rats. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 17:500–506; 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Spirin K. S.; Ljubimov A. V.; Castellon R.; Wiedoeft O.; Marano M.; Sheppard D.; Kenney M. C.; Brown D. J. Analysis of gene expression in human bullous keratopathy corneas containing limiting amounts of RNA. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 40:3108–3115; 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Stoilov P.; Castren E.; Stamm S. Analysis of the human TrkB gene genomic organization reveals novel TrkB isoforms, unusual gene length, and splicing mechanism. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 290:1054–1065; 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Widenfalk J.; Lundstromer K.; Jubran M.; Brene S.; Olson L. Neurotrophic factors and receptors in the immature and adult spinal cord after mechanical injury or kainic acid. J. Neurosci. 21:3457–3475; 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wu D.; Pardridge W. M. Neuroprotection with noninvasive neurotrophin delivery to the brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:254–259; 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ying H. S.; Weishaupt J. H.; Grabb M.; Canzoniero L. M.; Sensi S. L.; Sheline C. T.; Monyer H.; Choi D. W. Sublethal oxygen-glucose deprivation alters hippocampal neuronal AMPA receptor expression and vulnerability to kainate-induced death. J. Neurosci. 17:9536–9544; 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]