Abstract

CONTEXT:

The World Health Organization (WHO) has emphasized the need for reorientation of hospitals toward health promotion (HP).

AIMS:

This study explores health-care professionals' perception of barriers and strategies to implementing HP in educational hospitals of Isfahan Province in Iran.

SETTINGS AND DESIGN:

The study settings included four selective educational hospitals and the Treatment Administration affiliation to the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS:

A qualitative content analysis approach was employed in this study, with semi-structured in-depth interviews. Eighteen participants from hospital and accreditation managers, nurses, community medicine specialist, and directors of health-care quality improvement and accreditation participated in the study by purposeful sampling method. The data were analyzed using content analysis method.

RESULTS:

The barriers can be categorized into the following areas: (1) barriers associated with patient and community, (2) barriers associated with health-care professionals, (3) barriers associated with the organization, and (4) external environment barriers. The results were summarized into four categories as strategies, including: (1) marketing the plan, (2) identifying key people and training, (3) phasing activities and development of feasible goals, and (4) development of strategic goals of health promoting hospitals and supportive policies.

CONCLUSIONS:

The interactions of individual, organizational, and external environmental factors were identified as barriers to implementation of HP in hospitals. To hospital reorientation toward HP, prioritizing the barriers, and using the proposed strategies may be helpful.

Keywords: Health promoting hospital, health promotion, hospital, qualitative methods

Introduction

The health system faces numerous challenges, such as the need for a reduction in health-care costs and the effective prevention and management of noncommunicable diseases. In response to these the WHO has indicated the need for a reorientation of the health services away from focusing solely on illness and disease to one that considers both disease prevention and health promotion (HP).[1] Hence, the WHO launched the Health Promoting Hospitals (HPH) project in Europe in 1988 and established the HPHs Network in 1990 to HP reorientation in hospitals.[2] Because of several factors, hospitals are well placed to advocate for HP such as: the central role they play in providing health-care services within the community; consuming 40%–70% of the national health-care expenditure;[3] HP is a good strategy to improve quality in health care of hospital;[4] hospital access to a large number of people; hospital access to medical professional,[5] etc., Although the evidence now supports the effectiveness of HP in hospitals,[4] however, studies showed it is difficult to achieve HP reorientation in the hospital.[6] There is always criticism of the fact that health-care professionals devote most of their time to clinical duties and HP activities aside, may not even provide basic health education services.[7] Studies on the experiences of participating hospitals in the HP activities have resulted to varying challenges. In the Guo et al. study shortage in funds, personnel, time, and professional skills were the main barrier to HP in hospitals of Beijing.[8] In the Lee et al. study the most reported barriers were lack of insurance coverage of HP, staff detachment, incoherence of government policies, weak inter-sectorial link, and staff resistance to change. In the other studies, health-care professionals' reluctance to integrate HP their work routines has been identified as a major barrier. Based on the identified challenges, studies proposed strategies to facilitate HP implementation in hospitals (such as organizational capacity building with the provision of resources, knowledge, etc.).[6,8,9]

Since the establishment of HPH network, many progressions have been occurred. Participation in this network was more prevalent in the Europe at the beginning and nowadays has included hospitals from other continents.[10] As the other developing countries, HPH concept in Iran is very new and until the date, any hospitals are being developed as HPH. However, in line with the Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program, hospitals engage in some HP activities. The Iranian hospitals have a different level of readiness and requirement to form a HPH; moreover, some of hospitals are not adequately equipped to achieve the HPH. Despite many studies on the challenges of implementing HP in hospitals in developed countries, current barriers of the HP services in hospitals of Iran and other developing countries are unclear as well. Clear understanding of the current barriers can helpful to choose the right strategies for reorienting of hospitals to HP in Iran. This study is a part of the doctoral dissertation in the field of health education and promotion with the objective to identifying the effective factors and processes in the adoption of HP in hospitals. The aim of this substudy was to identify the experiences of multidisciplinary health-care professionals on barriers to implementation of HP in practice and formulating strategies to facilitate the movement hospitals toward HP.

Subjects and Methods

The qualitative research method was used in 2015 to explore the health professionals experiences on barriers exist to HP implementation in the hospitals of Isfahan, Iran. The study settings included; four selective educational hospitals and the accreditation unit of Treatment Administration affiliation to the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Iran. The study population was a group of hospital managers, nurses, doctors, directors of health-care quality improvement, and director of hospitals accreditation. The purposive sampling method was used to achieve the maximum heterogeneity of participants to include men and women from different professional groups and health-care settings. Inclusion criteria for these participants were: professional relevancy, engagement in HP activities and programs, at least 1 year of job experience, and willingness to talk about HP at hospital.

Data were collected using semi-structured person-to-person interviews with 18 participants. The audio recordings of the person-to-person interviews and focus group discussion were independently reviewed by three investigators and transcribed verbatim. Concurrent data accumulation and analysis were performed by conventional content analysis introduced by Graneheim and Lundman[11] using qualitative data analysis software MAXQDA. For this purpose, the data were read line by line, and the primary codes were extracted. Based on Lincoln and Guba's criteria,[12] the following procedures were applied to increase the credibility of the findings: triangulation method was used for data collection; the texts of the interviews and initial codes were returned to the participants, so that determine if the codes were relevant to their experiences; and interpretations were discussed within the research team.

To increase the dependability of the findings, external check of study reports were performed by two researchers with working experience in qualitative studies and who was not engaged in the present study. To increase the transferability of the findings, key participants were selected from different professional groups and health-care settings. To increase the conformability of findings, the researcher team committed to bracketing their interests and experiences in data analysis process.

This study received approval from the ethics committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Iran, with project number: 393761. All participants gave their oral consents for participation in this research and recording the interviews with audiotape recorder.

Results

Participant characteristics

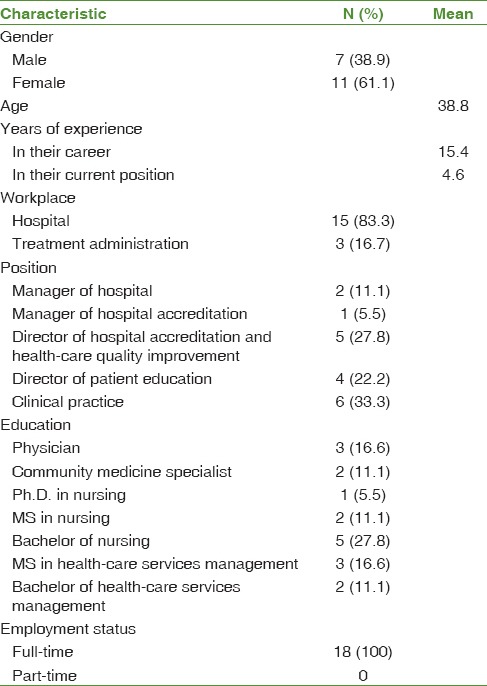

Totally 18 health professionals participated in the study. Most participants were female. The mean age of participants was 38.8 years. The mean years of experience in their careers and current positions were 15.4 and 4.6, respectively. All of the participants had full-time employment status. Most of the participants were nurse. Table 1 shows the characteristics of these participants.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants (n=18)

Barrier to health promotion in hospitals

The study data were based on the participants' experiences in implementing HP programs and activities in line with the health-care quality management programs. A wide range of barriers to integrating HP in hospital was discussed by participants. Some issues were closely related to individual factors, while others were more systematic and pertinent to the organizational and external environment factors as a whole.

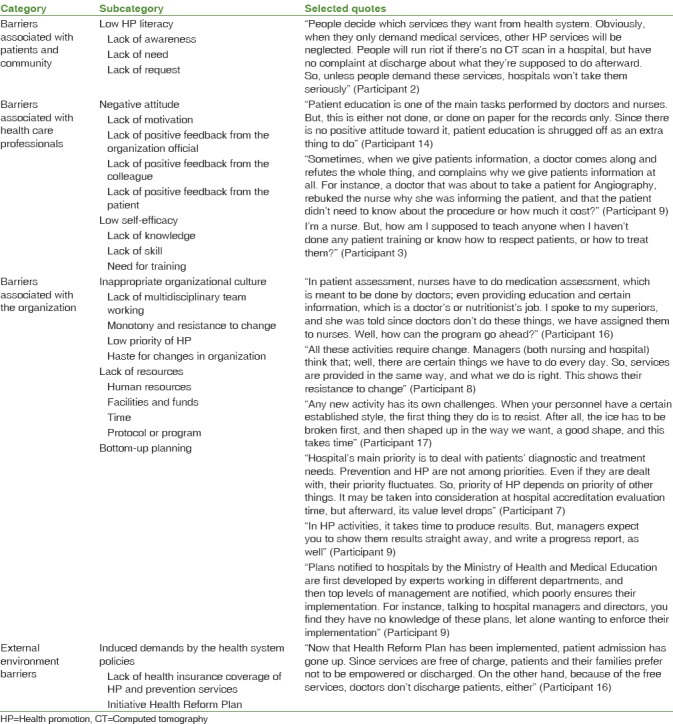

The barriers can be categorized into the following areas: (1) barriers associated with patient and community, (2) barriers associated with health-care professionals, (3) barriers associated with the organization, and (4) external environment barriers. Table 2 shows main categories and subcategories were generated from the study.

Table 2.

Barriers to implementation of health promotion in hospital

Barriers associated with patients and community

Participants referred to patients and the community as partners of the organization, who can have a decisive role in hospitals' move toward HP.

Low health promotion literacy

HP was introduced as the unfamiliar rights to patients and community, whose lack of knowledge and absence of feeling the need for these services prevent their participation in these programs. For as long as, there is no demand on the part of clients, hospitals will not prioritize these services, and will not feel obliged to implement HP services.

Barriers associated with health-care professionals

Negative attitude

Negative attitude of health-care professionals, especially doctors and managers was identified as a highly important barrier. Some participants believed that attitude was even more important than providing financial incentives and infrastructures.

Lack of motivation

All nurses considered poor motivation as a barrier to implementation of HP and blamed the absence of positive feedback from the organization officials, colleagues, and the patients as the main factor. Nurses revealed that lack of financial and nonfinancial incentives, equal rating of active and nonactive employees by the management and officials, negative feedback from patients and their relatives, and suppression by colleagues had led to their reluctance to perform beyond their routine medical duties.

“Therapist introducing herself to the patient is part of patient's HP rights. But, as it happens, they think you want something from them, money or something … Once I introduced myself to a patient, and he offered me his phone number!!” (Participant 3).

Low self-efficacy

Lack of HP knowledge, skill, and the need for further training were identified in this subcategory. Low self-efficacy adversely affects employees' participation in the implementation of HP. Participants' lack of HP planning skills, interaction with patients, and effective training were mentioned.

In hospitals, HP is an alien term, and most employees and managers have no knowledge of HP programs. Moreover, lack of understanding of and insight into objectives, philosophy, and activities involved impedes effective planning and implementation of HP.

The majority of participants believed they could not effectively participate in HP due to inadequate training, and emphasized the need for training and empowerment of managers and employees in HP planning and implementation.

Barriers associated with the organization

Subcategories of inappropriate organizational culture, lack of resources, and bottom-up planning identified in this field.

In appropriate organizational culture

Lack of multidisciplinary team working, monotony and resistance to change, low priority of HP, and haste for changes in organization were identified in this subcategory.

Lack of multidisciplinary team working – impose duties to nurses and other care team disengagement, especially doctors in activities such as patient assessment, patient education, health records … identified as barriers by all nurses and some officials.

Monotony and resistance to change – resistance of managers and employees and their desire to implement routine activities hinders new programs of HP.

In the opinion of a participant; integrating new programs is time-consuming and requires ice-breaking:

Low priority of health promotion – participants believed that because of patients' urgent medical needs, the focus is always on diagnostic and treatment activities, and prevention and HP activities are not among priorities of organization and have no fixed position in hospitals' value system.

Haste for changes in organization – Not scheduling different phases of implementation of new plans in hospitals and the management's haste to see effects and changes were identified as a factor for aborting these plans.

Lack of resources

Participants identified lack of resources as the biggest barrier, which included lack of human resources, facilities and funds, time, and a comprehensive protocol or program. The lack of human resources was cited in terms of both insufficient numbers and lack of expert workforce (such as specialists in health education and promotion, rehabilitation, and professional health). Lack of funds for HP services, lack of educational space and facilities, exercise facilities, and healthy nutrition were proposed as barriers to HP in patients and employees. The implementation of HP in hospitals requires a comprehensive program, and totally transparent predetermined protocol and guidelines. In the absence of these, HP activities will be limited and sporadic.

Bottom-up planning

Quality improvement officials in all hospitals have the duty to develop the annual HP operational plan to meet hospital accreditation standards. However, some of them believed that implementation of the plan without the involvement of the management will be poorly enforced.

External environment barriers

Induced demands by the health system policies

Lack of health insurance coverage of HP and prevention services and the existing relevant initiatives at the Ministry of Health and Medical Education, such as the Health Reform Plan, were identified in this subcategory.

Some participants believed that certain policies, inadequate health insurance coverage of prevention and HP services and implementation of the nationwide Health Reform Plan have led to overuse of medical services by both the community and doctors. These policies have led to poor commitment of community and patient toward their own health, and also poor commitment of doctors' to empowerment patients and the community.

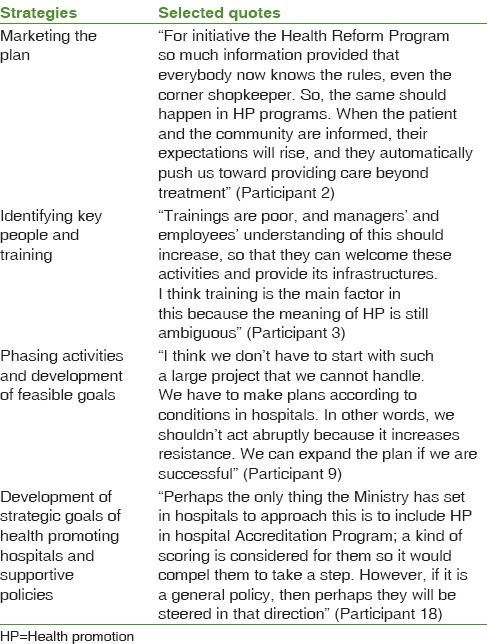

Strategies facilitating implementation of health promotion in hospitals

Four full replication strategies were identified as the primary key steps to facilitate reorientation hospitals toward HP [Table 3].

Table 3.

Strategies for implementation of health promotion in hospital

Marketing the plan

Participants believed that making patients and the community aware and sensitive to HP services available in hospitals leads to the culture of HP and increased demand and expectation from hospitals. This strategy is also effective in attracting charitable donations for supporting prevention and HP services in hospitals.

Identifying key people and training

Hospital employees and managers have a major role in implementation and success of hospital services. Identifying key people in hospital and representation from all managerial and clinical levels (hospital manager, quality improvement official, health-care staff at the hospital, and members of the hospital executive management committee), and training cascade in organizations is an important step in the implementation of HP in hospitals.

Phasing activities and development of feasible goals

Participant believed that full implementation of HP principles was unattainable due to the absence of necessary infrastructures. However, phasing activities according to existing facilities and initiating the program with small and attainable projects can be effective.

Development of strategic goals of health promoting hospitals and supportive policies

Concessions and rank hospitals for HP degree can encourage hospitals managers to take steps to make HPH. However, there is no plan to reorientation country's hospitals in terms of HP at the Ministry of Health and Medical Education level. Some participants believed attention to this subject in the goals and vision of the Ministry of Health and Medical Education can ensure supportive policies, which can, in turn, ensure support from insurance organizations and partnership of other community organizations (such as, welfare, environment, Radio, and TV …) with hospital in implementing HP.

Discussion

This study was conducted to explore experiences of multidisciplinary health-care professionals of barriers to and facilitating strategies for implementation of HP in hospitals. Several barriers were identified at different levels of patients and community, health-care professionals, organization, and external environment. Strategies identified included marketing plan, identifying key people and training, phasing programs, development of feasible goals, and development of strategic goals of HPH and supportive policies.

The results showed that lack of knowledge about HP and its importance reduces patients' and community's expectations of hospitals and their nonparticipation in most HP activities. Failure to facilitate the participation of the target population has also been referred to in other studies.[13] Conventionally, hospitals have mainly had a diagnostic and treatment role, and a holistic approach to health has not been expected of them.[3] Marketing HP services with the aim to affect public opinion and behavior of a large group of people was identified as an effective strategy in this area. Other studies have also identified marketing as an effective strategy to attract support for HP services.[14] Personnel are the key element for the establishment and continued implementation of HP in hospitals.[3,9] In agreement with the present study, in a study by Aghakhani et al., participants did not consider health education activities their own responsibility,[15] and personnel's negative attitude, lack of HP knowledge, poor skill and self-efficacy, and low motivation were identified as barriers.[3,9,16,17,18,19] There is no self-efficacy for implementation of HP activities, and the need for teaching the concept and skills such as interaction with patients, planning, and teaching skills is deeply felt, which highlights the importance of education and training of personnel. Participants also cited lack of education and proposed initiation of education for key hospital personnel as an effective strategy to facilitate hospital reorientation toward HP. In their study, Wieczorek et al. also proposed education as an effective strategy to overcome barriers found among health-care professionals.[6] Moreover, the right feedback from hospital managers and directors and rewarding personnel according to their efforts can increase their motivation for participation.

In this study, another theme was concerned with organizational barriers that indicated inadequate organizational support for HP. Similar results were also found in other studies.[6,15,16,20,21] In Miseviciene and Zalnieraitiene and Aujoulat et al. study, nonparticipation of the multidisciplinary care team and imposing extra duties on nurses were identified as barriers.[20,22] HP relies on interdisciplinary activities,[3] and a coordinator in hospital and an external regulator can help eliminate this challenge. Monotony and resistance to change was another barrier that was also identified in a study by Lee et al.[9] Studies show that integration of hospital Accreditation Program and HPH can effectively reduce resistance in hospitals.[8,9] Since in Iran, Hospital Accreditation and Quality Assurance Programs include elements of HP; they have the right capacity for reducing resistance in hospitals. Participants believed that the culture of haste and not phasing plans were also barriers to effective implementation of the plan. Johnson and Nolanshowed that HP tasks and vision must be realistic and based on available resources.[23] In the present study, participants believed that in the absence of necessary infrastructures, the best strategy was to phase plans and develop feasible goals according to existing status. According to the World Health Organization, allocation of resources, and HP as a hospital mission and value are elements of HP standards in hospitals.[24] Taking these elements into account together with bottom-up planning approach can ensure implementation of HP in hospitals.

In the opinion of participants, certain ruling policies such as type of services covered by insurance and implementation of Health System Reform Plan have led to reduced commitment of doctors, patients, and the community to HP services. In other countries, lack of insurance covering HP services was considered a barrier.[3,9] Implementation and integration of HP in daily activities of hospitals require a supportive external environment such as policies and rules associated with HP and insurance support for HP services.[3] In this respect, an identified strategy was the development of strategic goals of HPH and creating supportive policies, which can help attract insurance companies' and other organizations' support.

Conclusions

A combination of individual, organizational, and external environmental factors was proposed as barriers to implementation of HP in hospitals. Hospital reorientation toward HP requires managers and policy-makers at various levels of health system to consider barriers and strategies identified.

Given the few studies conducted in Iran; it is recommended that further investigation be conducted in other hospitals to identifying more characteristics which can facilitate hospital reorientation toward HP. In addition to the perspective of health-care professionals, investigating patients' and the community's understanding can also provide a clearer insight.

Limitations

In the present study, limitations included participants' lack of proper understanding of HP activities due to the newness of the concept. However, experiences provided by health-care professionals from various disciplines were able to provide an understanding of barriers and strategies for future applications.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was supported by Isfahan University of Medical Science. Ph.D dissertation in health education and promotion at Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Iran, 2015 (Project No: 393761).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

This article is resulted from Ph.D. dissertation in health education and promotion at Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Iran, 2015 (Project No: 393761). The authors express their gratitude to health-care staff for their cooperation and to Treatment Administration and Department of Research and Technology of Isfahan University of Medical Science for their support.

References

- 1.WHO. Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. First International Conference on Health Promotion, Ottawa 21 November, 1986. WHO/HPR/HEP/95.1. 1986. [Last accessed on 2014 May 10]. Available from: http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/ottawa/en/index4.html .

- 2.Pelikan JM, Krajic K, Lobnig H, Conrad G. Feasibility, Effectiveness, Quality and Sustainability of Health Promoting Hospital Projects: Conrad. 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee CB, Chen MS, Powell MJ, Chu CM. Organisational change to health promoting hospitals: A review of the literature. Springer Sci Rev. 2013;1:13–23. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Groene O, Jorgensen SJ. Health promotion in hospitals – A strategy to improve quality in health care. Eur J Public Health. 2005;15:6–8. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cki100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. The International HPH Network. 2014. [Last accessed on 2018 Mar 14]. Available from: http://hphnet.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=category&id=9&Itemid=5 .

- 6.Wieczorek CC, Marent B, Osrecki F, Dorner TE, Dür W. Hospitals as professional organizations: Challenges for reorientation towards health promotion. Health Soc Rev. 2015;24:123–36. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whitehead D. Health promoting hospitals: The role and function of nursing. J Clin Nurs. 2005;14:20–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.01012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee CB, Chen MS, Chien SH, Pelikan JM, Wang YW, Chu CM, et al. Strengthening health promotion in hospitals with capacity building: A Taiwanese case study. Health Promot Int. 2015;30:625–36. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dat089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee CB, Chen MS, Wang YW. Barriers to and facilitators of the implementation of health promoting hospitals in Taiwan: A top-down movement in need of ground support. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2014;29:197–213. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. The International Network of Health Promoting Hospitals and Health Services: Integrating Health Promotion into Hospitals and Health Services. World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. 2007. [Last accessed on 2018 Mar 14]. pp. 1–23. Available from: www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/99801/E90777.pdf .

- 11.Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24:105–12. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Polit D, Beck C, Hungler B. Vol. 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2006. Essentials of Nursing Research, Methods, Appraisal & Utilization; pp. 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whitehead D. The European Health Promoting Hospitals (HPH) project: How far on? Health Promot Int. 2004;19:259–67. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dah213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orlandi MA. Promoting health and preventing disease in health care settings: An analysis of barriers. Prev Med. 1987;16:119–30. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(87)90011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aghakhani N, Nia HS, Ranjbar H, Rahbar N, Beheshti Z. Nurses' attitude to patient education barriers in educational hospitals of Urmia university of medical sciences. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2012;17:12–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo XH, Tian XY, Pan YS, Yang XH, Wu SY, Wang W, et al. Managerial attitudes on the development of health promoting hospitals in Beijing. Health Promot Int. 2007;22:182–90. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dam010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walthew P, Scott H. Conceptions of health promotion held by pre-registration student nurses in four schools of nursing in New Zealand. Nurse Educ Today. 2012;32:229–34. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2011.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farahani MA, Mohammadi E, Ahmadi F, Mohammadi N. Factors influencing the patient education: A qualitative research. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2013;18:133–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McHugh C, Robinson A, Chesters J. Health promoting health services: A review of the evidence. Health Promot Int. 2010;25:230–7. doi: 10.1093/heapro/daq010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miseviciene I, Zalnieraitiene K. Health promoting hospitals in Lithuania: Health professional support for standards. Health Promot Int. 2013;28:512–21. doi: 10.1093/heapro/das035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee CB, Chen MS, Powell M, Chu CM. Achieving organizational change: Findings from a case study of health promoting hospitals in Taiwan. Health Promot Int. 2014;29:296–305. doi: 10.1093/heapro/das056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aujoulat I, Le Faou AL, Sandrin-Berthon B, Martin F, Deccache A. Implementing health promotion in health care settings: Conceptual coherence and policy support. Patient Educ Couns. 2001;45:245–54. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(01)00188-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson A, Nolan J. Health promoting hospitals: Gaining an understanding about collaboration. Aust J Prim Health. 2004;10:51–60. [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization. Standards for Health Promotion in Hospitals: WHO Regional Office for Europe. 2004 [Google Scholar]