Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

Beta-thalassemia is the most severe form of thalassemia major in which where the person needs regular blood transfusions and medical cares. The genetic experiment of prenatal diagnosis (PND) has been effective in the diagnosis of fetus with thalassemia major. This study was aimed to evaluate educational interventions on perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, cues to action and self-efficacy in beta-thalassemia carriers and suspected couples on doing a PND genetic test in Andimeshk.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

In this quasi-experimental study, 224 beta-thalassemia carriers and suspected couples were randomly assigned to intervention and control groups. The data were collected using a researcher-made validated questionnaire using the self-administrated method. Before the intervention, questionnaires for both groups were completed, and then, an educational intervention was done for the intervention group during a month in four sessions for 30 min. After 2 months, the questionnaire was completed again by both groups. Data were analyzed using SPSS software version 20.

RESULTS:

There was no significant difference in the mean score of health belief model (HBM) variables and behavior between intervention and control groups before intervention (P < 0.05). However, after the educational intervention, the significant statistical difference in the mean score of perceived sensitivity, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, guidance for action, self-efficacy, and behavior of PND β-thalassemia genetic tests was observed between the intervention and control groups. (P < 0.001).

CONCLUSION:

Educational programs based on HBM can increase HBM constructs, behavior, and self-efficacy of beta-thalassemia carrier couples for doing beta-thalassemia PND.

Keywords: Andimeshk, beta thalassemia carrier couples, health belief model, prenatal diagnosis

Introduction

Thalassemia is not only an important public health problem but also a socioeconomic issue in many countries in the region.[1] Thalassemia major is a chronic hematological disorder due to hemoglobinopathy.[2] Beta-thalassemia is a diverse group of genetic disorders in the production of hemoglobin, due to decreased production of β-globin chains.[3] Beta-thalassemia major is a complex disease requiring special medical treatment, and these patients need to have regular blood transfusions and iron transplant (chelation therapy) to survive.[4] Thalassemia is the most common genetic disease in the world[5] with the highest prevalence in the Mediterranean and the equatorial regions and regions near the equator in Africa and Asia.[6] Iran has about 20,000 thalassemic patients and 3 million carriers, and Khuzestan province is one of the provinces most affected by the disease.[7,8] Several studies indicate that chronic diseases such as thalassemia have an undesirable effect on the mental health of patients and their families.[9] Patients not only need specific drugs and medical cares but also they are anxious about probable early death and feeling disappointed with a tendency for isolation.[10] About 80% of the patients with thalassemia major have had at least one psychiatric disorder.[2] Most young patients with thalassemia major are facing severe psychological problems.[11] The psychosocial burden on children caused by thalassemia major affects many aspects of their life such as education, sports, and social interactions.[12] About 71% of the parents of children with thalassemia major are worried about the future of their children, relatives view and have some levels of conflict with their spouse, ultimately suffering from depression.[13] Parents of these patients are constantly concerned about the health and future of their children.[14] The quality of life of children with beta-thalassemia major and their family members is low.[15] Parents of children with beta-thalassemia major, experience a wide range of problems such as helplessness and stigmatization.[16] This includes a range of psychosocial problems such as worrying about the disease severity and the future of children.[17] In addition, mothers of children with thalassemia have very little knowledge and an undesirable attitude towards the disease.[18] Some studies also confirm inadequate awareness of thalassemic patients' parents regarding the disease; therefore, it is necessary to provide appropriate education programs.[19] The training intervention using health belief model (HBM) is effective in changing attitudes and practice.[20] Participant's desire for information about thalassemia prevalence implies their interest to know the severity of thalassemia and assess their risk of getting the genetic disorder.[21] This conforms with the HBM, where any action for preventing illnesses, depends on the individual's perception to susceptibility to acquiring, and awareness of the benefits of reducing the threat of disease.[21] The effectiveness of any educational program widely depends on the using of appropriate theories and models. HBM was designed in the 1950s by social psychologists. The key constructs of this model are: perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, cues to action, and self-efficacy.[22] There was no record in literature available about our research field. We examined the effects of an educational intervention based on HBM on prenatal diagnosis (PND) of beta-thalassemia in beta-thalassemia carriers and suspected couples in Andimeshk City.

Materials and Methods

In this quasi-experimental study (pretest/posttest), 224 cases of beta-thalassemia carriers and final suspects couples in Andimeshk city were investigated. At the initial stage of study beta-thalassemia carriers and suspected couples in urban and rural areas were identified. Then, patients were randomly divided into two groups, intervention, and control. To prevent bias in the study, patients were matched regarding beta-thalassemia carriers, suspected couples for PND beta-thalassemia test and history of abortion among patients with thalassemia major. Inclusion criteria included the availability, official marriage and tendency for pregnancy and the exclusion criteria were: divorced, uncooperative, migrated couples, and couples having children with thalassemia major. To gather data a questionnaire was developed by researchers. The questionnaire was built-up of three parts; in the first part of the questionnaire, participants were asked to provide demographic and general information. The second part included 35 questions related to HBM structures. The third part of the questionnaire asked participants to provide behavioral question to mark the “No” or “Yes.” One score was allocated to “Yes” answers and 0 to “No” answers. Questionnaire of HBM structures was set as Linker four-option questions from definitely disagree to definitely agree. Based on these four options, scores from one to four was assigned. For each variable including perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, cues to action, and self-efficacy, five questions were intended.(A score from at least 5–20). For quantification of the validities, the questionnaire was sent to the experts of Health Education and based on their comments the content validity ratio and the Content Validity Index was verified. For questionnaire reliability verification, a pilot stage was performed on 24 beta thalassemia carrier couples, which were excluded in the original study. Internal consistency reliability of different parts of the questionnaire was calculated after data collection using Chronbach's alpha coefficient with confidence interval of 95%. The overall reliability of the research instrument was confirmed by calculating Chronbach's alpha coefficient of 80%. Chronbach's alpha coefficient for HBM instrument, perceived susceptibility as (72%), perceived severity as (90%), perceived benefits as (86%), perceived barriers as (81%), cues to action as (92%), and self-efficacy as (62%). Cronbach's alpha coefficient for behavior instrument of 85% was achieved. However, the questionnaire was designed without the name of participants, but we obtained formal consent from patients for the sake of research ethics regulations. The pretest was conducted for test and control groups after confirming the validity and reliability of the questionnaire. After the initial analysis of data, the educational needs of the patients were determined, and an educational content for intervention was prepared based on the pretest data analysis and educational objectives. The educational program was conducted for the intervention group, during 1 month in four sessions for 30 mins, in the form of lectures, group discussions and distribution of pamphlets. Two months after the educational intervention, posttest was carried out simultaneously in both the intervention and the control groups. Data were analyzed using SPSS 20 software with a significant level of P < 0.05. Chi-square test was used to examine the differences in qualitative demographic variables. To examine quantitative demographic variables, the mean score of HBM constructs and behavioral variable (after educational intervention) were used in independent t-test and Mann–Whitney tests. Paired t-test, and Wilcoxon test were used to compare the mean score of HBM constructs and behavioral variable before and after the educational intervention.

Results

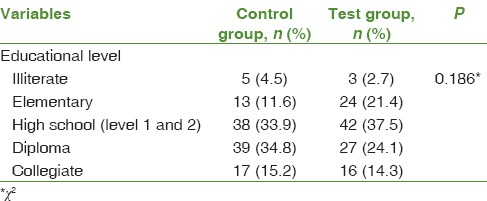

In this study, a total of 224 beta thalassemia carriers and suspected couples were examined (50% of females) in the age range 17–55 years. The mean age and standard deviation of the patients were 31.16 ± 6.89 years. Based on the Chi-square test, the comparison of the level of education in the two intervention and control groups before intervention did not show a significant difference (P = 0.186) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Pretest comparison of education level for intervention and control group

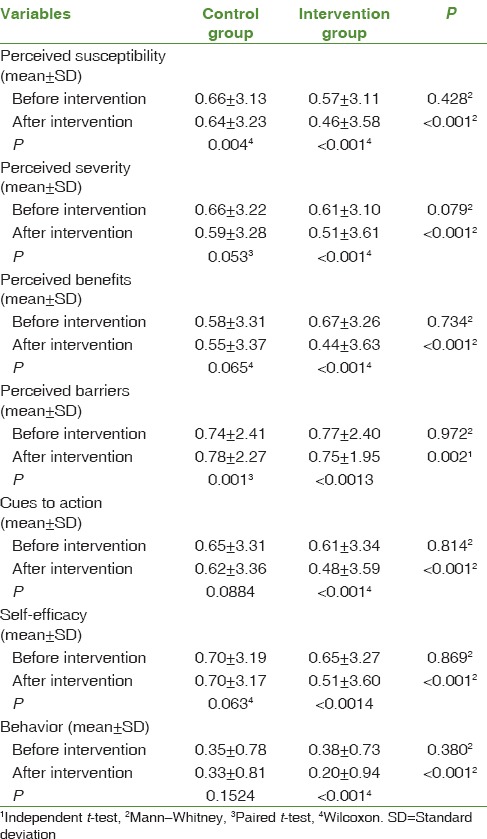

Using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and determining the distribution of the normal traits of the patients, parametric and nonparametric indices were used proportional to the hypotheses. The independent t-test indicates no significant statistical difference between the two groups with regard to their age distribution (P = 0.384). Based on the Chi-square test, no significant statistical difference was found between the two groups related to their education level (P = 0.186). The results show that there are no significant differences between the mean score of all HBM structures that included perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, cues to action and self-efficacy (P > 0.05) and behavior (doing beta-thalassemia PND) (P = 0.380) among two groups before the intervention, while results indicate that after intervention there is a significant difference between the mean scores of all structures (P < 0.05) and behavior (P < 0.001) among the two groups. The difference in perceived barriers structure was statistically significant, but negative (P = 0.002). The results show that there are no significant statistical differences between the mean scores of pretest and posttest in perceived severity, perceived benefits, cues to action, self-efficacy and behavior in control group (P > 0.05). However, there is a significant statistical difference between the mean scores in their perceived susceptibility (P = 0.004) and perceived barriers (P = 0.001) [Table 2]. Thus, we observed a significantly different mean score of perceived susceptibility before and after intervention even in the control group.

Table 2.

Comparison between changes in the behavior and constructs of health belief model

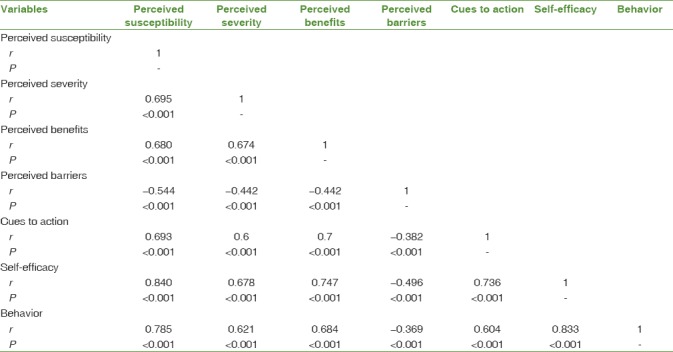

In the intervention group, there was a significant difference (P < 0.001) between the mean scores before and after the educational intervention of all HBM structures and performing beta thalassemia PND test Spearman's correlation coefficient results show that the correlation coefficient between mean scores of perceived susceptibility and behavior (P < 0.001, r = 0.785), perceived severity and behavior (P < 0.001, r = 0.621), perceived benefits and behavior (P < 001, r = 0.684), cues to action and behavior (P < 0.001, r = 0.604), self-efficacy, and behavior (P < 0.001, r = 0.833) of performing beta-thalassemia PND experiment in the beta-thalassemia carrier and suspected couples were positive and significant. However, spearman's correlation coefficient between the perceived barriers and behavior (P < 0.001, r = −0.369) were negative and significant [Table 3].

Table 3.

Correlation between constructs of the health belief model and behavior (n=224)

Furthermore, there was a positive and significant correlation between the internal mean score of HBM structures (except for barriers perceived). Meanwhile, the results show a negative significant correlation between the perceived barriers with other HBM structures.

Discussion

The main focus of this study is to encourage participants to perform PND thalassemia genetic testing using HBM-based educational intervention. The results show that HBM based educational program can significantly increase some HBM structures including perceived susceptibility, perceived benefits and improving self-efficacy and our expected behavior (doing PND beta-thalassemia test). The results of other studies also show the effectiveness of HBM model on preventive behaviors.[23,24,25] The results of this study show that the mean score of perceived susceptibility between two groups before intervention were similar, while after intervention a significant difference was observed in the mean score of perceived susceptibility, after the intervention thereby showing the probability of how much the participants would expose themselves to pregnancy with a serious risk of thalassemia major in their children. The effectiveness of our educational program based on HBM is consistent with the findings of studies in other fields.[26,27] The difference in perceived severity between intervention group and control group was statistically significant. The test group perceived more severity for taking care of children with thalassemia major. Intervention group also perceived more severity of thalassemia major on childrens' lives with weakness, fatigue, and depression. This result is consistent, with the findings of some researchers in regards to the perceived severity of illnesses using HBM.[28,29,30] However, some studies did not show significant changes in perceived severity after educational program based on HBM.[31] This study like other studies[26,32,33] show the effectiveness of some educational interventions in increasing perceived susceptibility. The results of this study show that mean score of perceived benefits after the educational intervention in intervention group significantly increased in comparison to control group. This means the intervention group perceived more benefits of doing PND test for beta-thalassemia. Our Findings also show the effectiveness of some educational program based on HBM of perceived benefits in the patients studied.[34] The results of this study show a significant difference between the two groups after an educational intervention regarding perceived barriers. The results show that there are no significant statistical differences between the mean scores of pretest and posttest in perceived severity, perceived benefits, cues to action, self-efficacy, and behavior in the control group (P > 0.05). However, there is a significant statistical difference between the mean scores in their perceived susceptibility (P = 0.004) and perceived barriers (P = 0.001). The increased sensitivity in the control group could be due to the information received through the staff of the health centers in the framework of the country's program for the treatment of β-thalassemia disease. However, the impact of the research questionnaire (in the pretest and posttest) should not be ignored.

After educational intervention, perceived barriers in intervention group significantly reduced. This confirms the results of previous studies but in different fields.[26] However, other studies show a reduction in perceived barriers in the experimental group after the intervention.[34] In this study, the most noted cues to action in the intervention group were: Insistence by wife, individual training, and consultations via phone by healthcare workers for doing PND beta thalassemia test. In other studies,[34] the most noted cues to action were; the influence of physicians, healthcare workers, patients' families, radio and by reading books. In this study after the educational intervention, the mean score of self-efficacy in the intervention group compared to control group was significantly increased, this shows the effectiveness of our educational program, since self-efficacy has a strong impact on health behaviors. The findings of this study showed that doing PND beta-thalassemia tests to prevent the births with beta-thalassemia majorly depends on the level of self-efficacy of beta-thalassemia carrier and suspected couples. However other studies show the effectiveness of self-efficacy on nutrition and quality of life in diabetic patients.[26,35,36] Mean score of behavior in the intervention group significantly increased compared with the control group, this means after educational intervention, the intervention group was highly motivated to perform PND beta-thalassemia tests, as we expected. The results of this study showed that the correlation coefficient between HBM structures (except perceived barriers) with our expected behavior “doing PND beta-thalassemia genetic test” was positive and significant., Meanwhile the correlation coefficient between the perceived barriers to behavior was conversely significant. This confirms the results of other studies in the field of promoting self-care in patients with tuberculosis.[36]

Conclusion

Although theory-based and educational evaluation before intervention were the strengths of this study, low level of education in a considerable number of patients, and self-report data were the limitations of this study. Educational programs based on HBMs have a positive impact on low-cost prevention activities. In other words, beta thalassemia PND tests will prevent the new cases of thalassemia major leading to the promotion of family and community health. Hence, it seems that generalization of this kind of theory-based educational programs will be effective for preventive behaviors.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was financially supported by Research Affairs, Social Determinant of Health Research Center Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences Ahvaz, Iran.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This article is part of a master's thesis in health education in Public Health Department, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, which is registered as SDH-9410 in Social Determinant of Health Research Center and Ethics Code 1394-140 in Research Ethics Committee. The authors are grateful to all staff of Andimeshk City Health Center for their help related to implementation of this research, and also a special thanks to all couples who participated in this study.

References

- 1.Fucharoen S, Winichagoon P. Thalassemia and abnormal hemoglobin. Int J Hematol. 2002;76(Suppl 2):83–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03165094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aydin B, Yaprak I, Akarsu D, Okten N, Ulgen M. Psychosocial aspects and psychiatric disorders in children with thalassemia major. Acta Paediatr Jpn. 1997;39:354–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200x.1997.tb03752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Awadallah SM, Atoum MF, Nimer NA, Saleh SA. Ischemia modified albumin: An oxidative stress marker in β-thalassemia major. Clin Chim Acta. 2012;413:907–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2012.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atkin K, Ahmad WI. Living a ‘normal’ life: Young people coping with thalassaemia major or sickle cell disorder. Soc Sci Med. 2001;53:615–26. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00364-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orkin SH, Nathan DG, Ginsburg D, Look AT, Fisher DE, Lux IV. USA: Elsevier: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2008. Nathan and Oski's Hematology of Infancy and Childhood Saunders. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vichinsky EP, MacKlin EA, Waye JS, Lorey F, Olivieri NF. Changes in the epidemiology of thalassemia in North America: A new minority disease. Pediatrics. 2005;116:e818–25. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Latifi S, Zandian K. Survival analysis of β-thalassemia major patients in Khouzestan province referring to shafa hospital. Jundishapur Sci Med J. 2010;9:83–92. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Behrouzian F, Khajehmougahi N. Relationship of coping mechanism of mothers with mental health of their major thalassemic children. Sci J Iran Blood Transfus Organ. 2014;10:387–93. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keikhaie B, Kh Z, Pedram M. Prenatal diagnosis and frequency determination of α, β-thelassemia, S, D and C hemoglobinopathies globin mutations among ahwazian volunteers. Jundishapur Sci Med J. 2006;50:628–32. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaplan HI, Sadock BJ. Vol. 2. USA: Williams & Wilkins Co; 1989. Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Messina G, Colombo E, Cassinerio E, Ferri F, Curti R, Altamura C, et al. Psychosocial aspects and psychiatric disorders in young adult with thalassemia major. Intern Emerg Med. 2008;3:339–43. doi: 10.1007/s11739-008-0166-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gharaibeh H, Amarneh BH, Zamzam SZ. The psychological burden of patients with beta thalassemia major in Syria. Pediatr Int. 2009;51:630–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2009.02833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aziz K, Sadaf B, Kanwal S. Psychosocial problems of pakistani parents of thalassemic children: A cross sectional study done in Bahawalpur, Pakistan. Biopsychosoc Med. 2012;6:15. doi: 10.1186/1751-0759-6-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aydinok Y, Erermis S, Bukusoglu N, Yilmaz D, Solak U. Psychosocial implications of thalassemia major. Pediatr Int. 2005;47:84–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200x.2004.02009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zare K, Pordanjani SB, Pedram M, Pakbaz Z. Quality of life in children with thalassemia who referred to thalassemia center of Shafa Hospital. Jundishapur J Chron Dis Care. 2012;1:45–53. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abedi HA, Ghavimi S, Karimollahi M, Ghavimi E. Lack of support in the life of parents of children with thalassemia. J Gorgan Univ Med Sci Health Care. 2014;16:40–8. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borhany F, Najafi M. Knowledge and attitudes of mothers of children with thalassemia referenter to special medical center kerman toward sickness their children. J Qual Res Health Sci. 2013;11:32–40. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghazanfari Z, Arab M, Forouzi M, Pouraboli B. Knowledge level and education needs of thalassemic childern's parents of Kerman city. J Crit Care Nurs. 2010;3:3–4. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghofranipour F. Persian Thesis Presented for the Assistant Professor in Health Education. Vol. 1. Tarbiat Modares University; 1998. The Application of Health Belife Model on Prevention Brucellosis in the Shahrekord; pp. 12–5. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wong LP, George E, Tan JA. A holistic approach to education programs in thalassemia for a multi-ethnic population: Consideration of perspectives, attitudes, and perceived needs. J Community Genet. 2011;2:71–9. doi: 10.1007/s12687-011-0039-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. USA: John Wiley and Sons; 2008. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shamsi M, Tajik R, Mohammadbegee A. Effect of education based on health belief model on self-medication in mothers referring to health centers of arak. Arak Med Univ J. 2009;12:57–66. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heidarnia A. Factors influencing self-medication among elderly urban centers in zarandieh based on health belief model. Arak Med Univ J. 2011;14:70–8. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharifi-Rad G, Hazavei MM, Hasan-zadeh A, Danesh-Amouz A. The effect of health education based on health belief model on preventive actions of smoking in grade one, middle school students. Arak Med Univ J. 2007;10:79–86. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharifirad G, Kamran A, Azadbakht L. Efficacy of nutrition education to diabetic patient: Application of health belief model. Iran J Diabetes Lipid Disord. 2008;7:379–86. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Piri A. Effects of education based on health belief model on dietary adherence in diabetic patients. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2010;9:15. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghafari M. A Thesis for Degree of PhD, Tehran: Tarbiat Modares University; 2007. Comparing the Efficacy of Health Belief Model and Its Integrated Model in AIDS Education Among Male High School Students in Tehran. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Asadpour M, Ghofranipour F, Niknami S, Ardebili HE, Hajizadeh E, editors. Tabtiz University of Medical Sciences: 2011. Promotion and Maintenance of Preventive Behaviors From HIV, HBV and HCV Infections in Health Care Workers with Using Constructs of Health Belief Mode In Precede–Proceed Model The First International & 4th National Congress on health Education & Promotion, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wai CT, Wong ML, Ng S, Cheok A, Tan MH, Chua W, et al. Utility of the health belief model in predicting compliance of screening in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:1255–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Austin LT, Ahmad F, McNally MJ, Stewart DE. Breast and cervical cancer screening in hispanic women: A literature review using the health belief model. Womens Health Issues. 2002;12:122–8. doi: 10.1016/s1049-3867(02)00132-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aljasem LI, Peyrot M, Wissow L, Rubin RR. The impact of barriers and self-efficacy on self-care behaviors in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2001;27:393–404. doi: 10.1177/014572170102700309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cerkoney KA, Hart LK. The relationship between the health belief model and compliance of persons with diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1980;3:594–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.3.5.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sarani M. The Study for Health Belief Model Efficiency in Adopting Preventive Behaviors in the Sistan Region Tuberculosis Patients 2009-2010 Medical Sciences and Health Services Zahedan: School of Public Health. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bandura A. The assessment and predictive generality of self-percepts of efficacy. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1982;13:195–9. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(82)90004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heidari M, Alhani F, Kazemnejad A, Moezzi F. The effect of empowerment model on quality of life of diabetic adolescents. Iran J Pediatr. 2007;17(Suppl 1):87–94. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alizadeh-Siuki H, Izadirad H. The impact of educational intervention based on health belief model on promoting self-care behaviors in patients with smear-positive pulmonary tb. Iran J Health Educ Health Promot. 2014;2:143–52. [Google Scholar]