Abstract

Background:

Immediate implant placement has advantages such as requiring fewer surgical procedures and decreased treatment time; however, unpredictable soft- and hard-tissue outcome is a problem. This study aimed to compare the soft-tissue esthetic outcome of single implants placed in fresh extraction sockets versus those placed in healed sockets.

Materials and Methods:

This cross-sectional, retrospective study was performed on 42 patients who received single implants. Twenty-two patients with a mean age of 40.14 years received immediate implants while 18 patients with a mean age of 43.40 years were subjected to conventional (delayed) implant placement. The mean follow-up time was 14.42 ± 8.37 months and 18.25 ± 7.10 months in the immediate and conventional groups, respectively. Outcome assessments included clinical and radiographic examinations. The esthetic outcome was objectively rated using the pink esthetic score (PES).

Results:

All implants fulfilled the success criteria. The mean PES was 8.54 ± 1.26 and 8.10 ± 1.65 in the immediate and conventional groups, respectively. This difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.329). The two PES parameters, namely, the facial mucosa curvature and facial mucosa level had the highest percentage of complete score.

Conclusions:

Immediate and conventional single implant treatments yielded comparable esthetic outcomes.

Key words: Esthetics, immediate implant placement, pink esthetic score, single implant

INTRODUCTION

With a history of over 40 years, implant treatment is now a standard modality of care.[1,2] Previously, implants had to be placed after a 6–12-month healing period following tooth extraction. Such a long course of treatment also required several surgical procedures.[2,3] Advances in implant treatment have simplified and shortened the course of treatment and include flapless surgeries, immediate implant placement, and immediate loading.[3,4]

The physiological process of healing of extraction sockets starts immediately after tooth extraction and eventually results in a reduction in height (vertical ridge resorption) and width (horizontal ridge resorption) of alveolar process.[5,6,7] Immediate implant placement has been suggested to preserve the crestal bone. Some authors have stated that immediate implant placement in fresh extraction sockets maintains the contour of the residual ridge and prevents bone loss; therefore, it can have favorable effects on esthetics.[5,8,9] In contrast, some clinical and paraclinical studies have reported bone loss even after immediate implant placement.[5,10]

Several indexes have been proposed for esthetic assessment of implants. The papilla index, pink esthetic score (PES), implant-crown esthetic index, and PES/white esthetic score are among the most reliable indexes for this purpose.[4,11,12,13]

Considering the significance of esthetic outcome of peri-implant soft tissue, especially in the anterior region, in acceptance or refusal of recent treatment protocols such as immediate implant placement; this study aimed to compare the esthetic outcome of single implants placed in fresh extraction sockets versus those placed in healed sites.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Medical files of patients who received single implants by immediate or delayed placement were retrieved from the archives of a private dental clinic. This study was approved in the ethics committee of our university (Code: 678). The inclusion and exclusion criteria were as follows:

Inclusion criteria – (1) The presence of at least one natural tooth at each side of the respective implant, (2) implants placed at the site of single-rooted teeth, and (3) minimum of 6 months had to be passed since prosthetic delivery and loading of implant.

Exclusion criteria – (1) History of periodontal disease, (2) soft- or hard-tissue grafting before or during implant placement, (3) systemic diseases affecting periodontal conditions such as diabetes mellitus, (4) severe smoking, and (5) pregnancy.

The treatment process in patients who received immediate implants was as follows:

The flap was conventionally elevated. The teeth were gently luxated, and lateral forces were avoided to prevent damage to buccal and lingual plates. After atraumatic extraction of tooth, the extraction socket was debrided and rinsed with saline. Implant was then placed in the fresh socket after ensuring the presence of four intact bony walls without dehiscence or fenestration. In immediate implant placement, none of the patients received bone graft to fill the gap.

In patients who were subjected to conventional (delayed) implant placement, the treatment process was as follows:

Patients presented at least 6 months after tooth extraction. A mesiodistal crestal incision was made, and a full-thickness flap was elevated to expose alveolar bone.

Next, in both groups, implant placement site was prepared by specific drills under continuous irrigation, and implants were placed 0.5–1 mm beneath the bone crest according to the principles of 3D placement of implants. In both groups, implants were submerged and loaded after 6 months.

All clinical and radiographic examinations were carried out by an experienced periodontist who was not involved in the process of implant placement or prosthetic restoration. Clinical examination of each patient included measurement of pocket depth (PD), modified plaque index (MPI), modified bleeding index (MBI), mobility, and PES.[14]

PD was measured by inserting a standard titanium periodontal probe (noncolor-coded offset probe, Nordent, USA) at six areas of mesiobuccal, midbuccal, distobuccal, mesiolingual, midlingual and distolingual around each implant and recorded.

MPI was measured to assess plaque accumulation around implant. Score 0 indicated the absence of plaque, score 1 indicated plaque detectable by movement of probe in the sulcus, score 2 indicated visible plaque, and score 3 indicated abundant soft plaque.

MBI was used to assess bleeding on probing in six areas around each implant; 0 indicated no bleeding on probing, 1 indicated bleeding in separate points, 2 indicated bleeding in gingival margins, and 3 indicated abundant bleeding.

Mobility was graded clinically by holding the tooth firmly with one metallic instrument and one finger. Mobility beyond the physiologic range is termed abnormal or pathologic.

Pain, infection, neuropathy, and paresthesia were also assessed and some questions were asked from patients in this regard. This was done to determine the implant success rate according to the Alberktsson's criteria.[15]

For assessment of esthetic outcome, PES was determined for each patient. PES included five parameters of mesial papilla, distal papilla, facial mucosa curvature, facial mucosa level, and last parameter including three components of root surface convexity, soft-tissue color, and soft-tissue texture. Scores 0, 1, or 2 were allocated to each parameter. Mesial and distal papilla parameters were scored 2 in case of complete presence of papilla, 1 in case of partial presence of papilla, and 0 in case of absence of papilla. Facial mucosa curvature was defined as visibility of implant restoration margins over the facial soft tissue and scored 2 in case of complete adaptation, 1 in case of presence of small difference, and 0 in case of presence of significant difference. Facial mucosa level was assessed by comparing the level of mucosa relative to that of a control tooth and scored 2 in case of similarity, 1 in case of difference ≤1 mm, and 0 in case of difference ≥1 mm. Regarding the last parameter, color and appearance of soft-tissue indicate presence. The absence of inflammatory process which affects the appearance of implant restoration. In case of complete adaptation of all three factors with those in a control tooth, this parameter was scored 2, adaptation of two factors scored 1, and no adaptation was scored 0. The total score of 10 (2 × 5) for PES index was considered optimal. The acceptable score was ≥ 6. After scoring each PES parameter by a periodontist, standard clinical photographs (×1 magnification) were taken of the respective area using a digital camera (Canon).

Next, parallel radiographs were requested for each implant to assess the presence of radiolucency around implant and bone loss. Radiographs were scanned (300 DPI), and bone loss was quantified by measuring the distance between the implant shoulder and bone crest with 0.1 mm accuracy using Romexis Viewer 2.2.9 software. Radiographic findings were used to determine implant success rate according to the Alberktsson's criteria.

RESULTS

Demographics

This descriptive, analytical, cross-sectional, and retrospective study was conducted on 42 patients including 14 males (33.3%) and 28 females (66.7%) with a mean age of 41.73 years (range 22–63 years); of which, 22 underwent immediate and 20 underwent conventional (delayed) implant placement. The assessment of outcome was done 14.42 ± 8.37 months after treatment in the immediate group and 18.25 ± 7.10 months after treatment in the conventional group. The difference in this regard between the two groups was not statistically significant (P > 0.05).

Treated sites

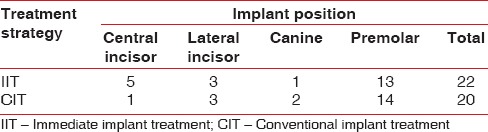

All teeth treated in this study were maxillary anterior teeth. Table 1 shows the distribution of implant sites.

Table 1.

Distribution of implant sites in the two groups

Bone loss

The mean bone loss was 0.62 ± 0.44 mm in the immediate and 0.43 ± 0.39 mm in the conventional group. The difference in this regard was not statistically significant between the two groups (P = 0.779).

Pink esthetic score

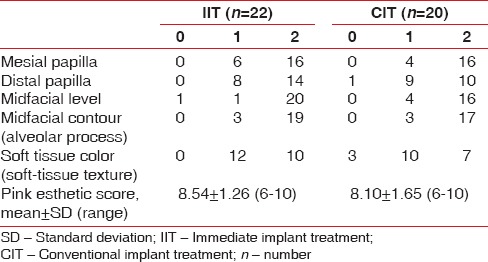

Table 2 compares the peri-implant soft-tissue esthetic outcome in the two groups. As shown in Table 2, the mean PES was 8.54 (range 6–10) in the immediate and 8.10 (range 6–10) in the conventional group. The difference in this regard was not statistically significant between the two groups (P > 0.05). No implant showed unacceptable PES in any of the two groups.

Table 2.

Esthetic outcome

Modified bleeding index, modified plaque index, and pocket depth

The mean MBI was 0.49 ± 0.44 in the immediate and 0.70 ± 0.50 in the conventional group. The difference in this respect was not statistically significant between the two groups (P = 0.164).

Table 3 compares the MPI in the two groups. The difference in this regard was not statistically significant between the two groups (P = 0.493).

Table 3.

Modified plaque index in the two groups

The mean PD was 2.72 ± 0.81 mm in the immediate and 2.56 ± 0.91 mm in the conventional group. The difference in this regard was not significant between the two groups (P = 0.552).

DISCUSSION

Immediate implant placement following tooth extraction has advantages such as saving time, esthetic appearance, and comfort for patients and disadvantages such as mid-facial gingival recession.[16] Many recent studies have emphasized that implant survival, osseointegration, and interdental crestal bone level are not negatively affected by immediate implant placement protocol.[17,18] In addition, a systematic review in 2014 showed better survival of crestal bone in immediate placement of implant compared to conventional placement.[19] Esthetic soft-tissue outcome around immediate implants is still a matter of debate considering no effect of this protocol on natural remodeling of tooth socket.

In the current study, none of the implants had any mobility, pain, infection, neuropathy, or paresthesia. The amount of bone loss in the two groups was within the success criterion reported by Alberktson.[15] Assessment of soft-tissue outcome in the current study was done using modified PES. Both groups acquired almost a complete score with no significant difference between the two, which was in line with the findings of similar previous studies.[20,21,22,23]

PES did not show any significant difference between the two groups regarding papillary height. This finding was in line with that of previous studies that found no significant difference in the papilla score between the two groups.[5,9,21,24,25] This finding was also in agreement with that of previous studies showing that papilla fullness is independent of the time of implant surgery relative to tooth extraction.[26,27] In other words, based on several studies, interdental papillary height depends on the bone peak of adjacent tooth, and time of implant placement has no effect on bone level.[28] Cosyn et al. in 2012 conducted a 3-year study on soft-tissue status around immediately placed implants and revealed that 1 year after treatment, the papilla had not been completely remodeled but showed significant regrowth especially in the mesial part over time. After 3 years, the papilla regained its primary height.[16] Accordingly, since the duration of the current study was <18 months, the papillary score still had a chance of improvement in the upcoming years.

Regarding the soft tissue around immediate single implants, midfacial gingival level has gained increasing attention in the recent studies. The current study showed no significant difference in facial mucosa level between the two groups, and 90.9% of immediate implants and 80% of conventional implants acquired a complete score in this respect. Some studies have reported high incidence of gingival recession (30%–40%) following immediate implant placement [27,29,30,31] while some others have reported limited resorption in the facial mucosa (0.5–1 mm) following immediate implant placement.[3,16,22,23,32] Based on Felice et al. study, soft-tissue levels score was significantly better at immediate implants as compared with delayed implants.[9] Some studies have reported that thin gingival biotype is an important, even the most important, factor responsible for midfacial gingival recession.[21,33] The presence of labial bone with adequate thickness and height is an important factor affecting long-term stability of gingival margin around implants.[34] Moreover, implant shoulder position also affects mid-facial gingival recession such that buccal shoulder of implant can increase the risk of gingival recession by three times. Therefore, accurate patient selection is the most important factor in this respect.[22,29] In other words, many factors such as technique of surgery, restorative treatment, technical expertise, buccal bone plate status, soft-tissue volumetric defects, and wound healing potential significantly affect midfacial gingiva and can compensate for the negative effect of immediate implant placement on mid-facial gingival status.[34]

Also according to the Systematic Review in 2016, no significant difference of the esthetic outcomes was reported following immediate as compared with conventional implant placement.[35]

In the current study, the three-component parameter of PES was not significantly different between the two groups either. This parameter had the lowest frequency percentage of acquiring a complete score compared to other parameters in the two groups (46.5% in the immediate and 36% in the conventional group).

In detailed assessment of findings, the most important factor responsible for not acquiring a complete score in most cases was found to be absence of adequate alveolar prominence (55% in the conventional group and 46.46% in the immediate group).

Cosyn et al. in their study in 2011 evaluated immediate implants using PES and reported that alveolar prominence was the parameter with the highest percentage of mismatch with the control tooth (30% mismatch).[16] The same authors in their study in 2013 reported that alveolar prominence gained the lowest score and great defects were noted in this parameter in over 15% of the cases.[21] In line with these findings, evidence shows that resorption of buccal bone plate occurs following tooth extraction with or without implant placement.[10,32] Thus, use of bone grafts with delayed resorption over the buccal surface of alveolar bone, especially in the esthetic zone may resolve this problem to some extent and help achieve more stable esthetic results.

Only a few studies have assessed biological conditions of the peri-implant soft tissue.[28] Wang et al. in 2013 showed that peri-implant soft tissue is an important confounding factor in this respect.[36] In the current study, the mean MBI was 0.49 ± 0.45 in the immediate and 0.70 ± 0.50 in the conventional group, with no significant difference between the two groups. These findings were in agreement with those of Cosyn et al. in 2013.[21] To put it simply, based on the current results, 36% of the areas in immediate group and 54% of those in the conventional group showed bleeding on probing while PI was very low in both groups such that 4.5% (one case) of samples in the immediate group and 10% of those (two cases) in the conventional group gained MPI score of 1. These results were in accordance with those of similar studies.[3,16,21] Relatively high BOP, especially in the conventional group despite low PI is not an uncommon finding around implants,[37,38,39] and is due to infiltration of inflammatory cells, probably because of microleakage around implant-abutment interface [40,41] and subgingival placement of restoration margins.[42] Probing depth in the current study was not significantly different between the two groups and was within the acceptable range. This finding was in agreement with the results of the only previous study found on this topic.[21] In general, biological soft-tissue findings in this study indicated stability of soft-tissue conditions, which is promising for prediction of soft-tissue outcome following both immediate and conventional placement of single implants.

CONCLUSIONS

This study showed that immediate placement of implants following tooth extraction is a valuable and predictable protocol comparable to conventional placement of single implants regarding survival rate, osseointegration, and esthetics.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lang NP, Pun L, Lau KY, Li KY, Wong MC. A systematic review on survival and success rates of implants placed immediately into fresh extraction sockets after at least 1 year. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2012;23(Suppl 5):39–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2011.02372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buser D, Bornstein MM, Weber HP, Grütter L, Schmid B, Belser UC, et al. Early implant placement with simultaneous guided bone regeneration following single-tooth extraction in the esthetic zone: A cross-sectional, retrospective study in 45 subjects with a 2- to 4-year follow-up. J Periodontol. 2008;79:1773–81. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.080071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Rouck T, Collys K, Cosyn J. Immediate single-tooth implants in the anterior maxilla: A 1-year case cohort study on hard and soft tissue response. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35:649–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belser UC, Grütter L, Vailati F, Bornstein MM, Weber HP, Buser D, et al. Outcome evaluation of early placed maxillary anterior single-tooth implants using objective esthetic criteria: A cross-sectional, retrospective study in 45 patients with a 2- to 4-year follow-up using pink and white esthetic scores. J Periodontol. 2009;80:140–51. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.080435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mangano FG, Mangano C, Ricci M, Sammons RL, Shibli JA, Piattelli A, et al. Esthetic evaluation of single-tooth morse taper connection implants placed in fresh extraction sockets or healed sites. J Oral Implantol. 2013;39:172–81. doi: 10.1563/AAID-JOI-D-11-00112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farmer M, Darby I. Ridge dimensional changes following single-tooth extraction in the aesthetic zone. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2014;25:272–7. doi: 10.1111/clr.12108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tan WL, Wong TL, Wong MC, Lang NP. A systematic review of post-extractional alveolar hard and soft tissue dimensional changes in humans. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2012;23(Suppl 5):1–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2011.02375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Missika P. Immediate placement of an implant after extraction. Int J Dent Symp. 1994;2:42–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Felice P, Zucchelli G, Cannizzaro G, Barausse C, Diazzi M, Trullenque-Eriksson A, et al. Immediate, immediate-delayed (6 weeks) and delayed (4 months) post-extractive single implants: 4-month post-loading data from a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Oral Implantol. 2016;9:233–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Favero G, Botticelli D, Favero G, García B, Mainetti T, Lang NP, et al. Alveolar bony crest preservation at implants installed immediately after tooth extraction: An experimental study in the dog. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2013;24:7–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2011.02365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fürhauser R, Florescu D, Benesch T, Haas R, Mailath G, Watzek G, et al. Evaluation of soft tissue around single-tooth implant crowns: The pink esthetic score. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2005;16:639–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2005.01193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jemt T. Regeneration of gingival papillae after single-implant treatment. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1997;17:326–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meijer HJ, Stellingsma K, Meijndert L, Raghoebar GM. A new index for rating aesthetics of implant-supported single crowns and adjacent soft tissues – The implant crown aesthetic index. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2005;16:645–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2005.01128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mombelli A, van Oosten MA, Schurch E, Jr, Land NP. The microbiota associated with successful or failing osseointegrated titanium implants. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1987;2:145–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1987.tb00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Albrektsson T, Zarb G, Worthington P, Eriksson AR. The long-term efficacy of currently used dental implants: A review and proposed criteria of success. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1986;1:11–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cosyn J, Eghbali A, De Bruyn H, Collys K, Cleymaet R, De Rouck T, et al. Immediate single-tooth implants in the anterior maxilla: 3-year results of a case series on hard and soft tissue response and aesthetics. J Clin Periodontol. 2011;38:746–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2011.01748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vignoletti F, Sanz M. Immediate implants at fresh extraction sockets: From myth to reality. Periodontol 2000. 2014;66:132–52. doi: 10.1111/prd.12044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kolerman R, Mijiritsky E, Barnea E, Dabaja A, Nissan J, Tal H, et al. Esthetic assessment of implants placed into fresh extraction sockets for single-tooth replacements using a flapless approach. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2017;19:351–64. doi: 10.1111/cid.12458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kinaia BM, Shah M, Neely AL, Goodis HE. Crestal bone level changes around immediately placed implants: A systematic review and meta-analyses with at least 12 months' follow-up after functional loading. J Periodontol. 2014;85:1537–48. doi: 10.1902/jop.2014.130722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lai HC, Zhang ZY, Wang F, Zhuang LF, Liu X, Pu YP, et al. Evaluation of soft-tissue alteration around implant-supported single-tooth restoration in the anterior maxilla: The pink esthetic score. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2008;19:560–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2008.01522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cosyn J, Eghbali A, Hanselaer L, De Rouck T, Wyn I, Sabzevar MM, et al. Four modalities of single implant treatment in the anterior maxilla: A clinical, radiographic, and aesthetic evaluation. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2013;15:517–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8208.2011.00417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen ST, Buser D. Esthetic outcomes following immediate and early implant placement in the anterior maxilla – A systematic review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2014;29(Suppl.g3.3):186–215. doi: 10.11607/jomi.2014suppl.g3.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Juodzbalys G, Wang HL. Soft and hard tissue assessment of immediate implant placement: A case series. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2007;18:237–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2006.01312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Felice P, Soardi E, Piattelli M, Pistilli R, Jacotti M, Esposito M, et al. Immediate non-occlusal loading of immediate post-extractive versus delayed placement of single implants in preserved sockets of the anterior maxilla: 4-month post-loading results from a pragmatic multicentre randomised controlled trial. Eur J Oral Implantol. 2011;4:329–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raes F, Cosyn J, Crommelinck E, Coessens P, De Bruyn H. Immediate and conventional single implant treatment in the anterior maxilla: 1-year results of a case series on hard and soft tissue response and aesthetics. J Clin Periodontol. 2011;38:385–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01687.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rompen E, Raepsaet N, Domken O, Touati B, Van Dooren E. Soft tissue stability at the facial aspect of gingivally converging abutments in the esthetic zone: A pilot clinical study. J Prosthet Dent. 2007;97:S119–25. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3913(07)60015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindeboom JA, Tjiook Y, Kroon FH. Immediate placement of implants in periapical infected sites: A prospective randomized study in 50 patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:705–10. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shi JY, Wang R, Zhuang LF, Gu YX, Qiao SC, Lai HC, et al. Esthetic outcome of single implant crowns following type 1 and type 3 implant placement: A systematic review. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2015;26:768–74. doi: 10.1111/clr.12334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Evans CD, Chen ST. Esthetic outcomes of immediate implant placements. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2008;19:73–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2007.01413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen ST, Darby IB, Reynolds EC. A prospective clinical study of non-submerged immediate implants: Clinical outcomes and esthetic results. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2007;18:552–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2007.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kan JY, Rungcharassaeng K, Liddelow G, Henry P, Goodacre CJ. Periimplant tissue response following immediate provisional restoration of scalloped implants in the esthetic zone: A one-year pilot prospective multicenter study. J Prosthet Dent. 2007;97:S109–18. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3913(07)60014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lops D, Romeo E, Chiapasco M, Procopio RM, Oteri G. Behaviour of soft tissues healing around single bone-level-implants placed immediately after tooth extraction A 1 year prospective cohort study. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2013;24:1206–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2012.02531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nisapakultorn K, Suphanantachat S, Silkosessak O, Rattanamongkolgul S. Factors affecting soft tissue level around anterior maxillary single-tooth implants. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2010;21:662–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2009.01887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buser D, von Arx T, Ten Bruggenkate C, Weingart D. Basic surgical principles with ITI implants. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2000;11(Suppl 1):59–68. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.2000.011s1059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yan Q, Xiao LQ, Su MY, Mei Y, Shi B. Soft and hard tissue changes following immediate placement or immediate restoration of single-tooth implants in the esthetic zone: A Systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2016;31:1327–40. doi: 10.11607/jomi.4668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang R, Zhao W, Tang ZH, Jin LJ, Cao CF. Peri-implant conditions and their relationship with periodontal conditions in Chinese patients: A cross-sectional study. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2014;25:372–7. doi: 10.1111/clr.12114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lorenzoni M, Pertl C, Polansky R, Wegscheider W. Guided bone regeneration with barrier membranes – A clinical and radiographic follow-up study after 24 months. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1999;10:16–23. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.1999.100103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ozkan Y, Ozcan M, Akoglu B, Ucankale M, Kulak-Ozkan Y. Three-year treatment outcomes with three brands of implants placed in the posterior maxilla and mandible of partially edentulous patients. J Prosthet Dent. 2007;97:78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chang M, Wennström JL, Odman P, Andersson B. Implant supported single-tooth replacements compared to contralateral natural teeth. Crown and soft tissue dimensions. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1999;10:185–94. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.1999.100301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Broggini N, McManus LM, Hermann JS, Medina RU, Oates TW, Schenk RK, et al. Persistent acute inflammation at the implant-abutment interface. J Dent Res. 2003;82:232–7. doi: 10.1177/154405910308200316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Piattelli A, Vrespa G, Petrone G, Iezzi G, Annibali S, Scarano A, et al. Role of the microgap between implant and abutment: A retrospective histologic evaluation in monkeys. J Periodontol. 2003;74:346–52. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.3.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jemt T, Pettersson P. A 3-year follow-up study on single implant treatment. J Dent. 1993;21:203–8. doi: 10.1016/0300-5712(93)90127-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]