Abstract

Background:

Several studies have reported an association between periodontal disease and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). However, heterogeneity of results suggests that there is insufficient evidence to support this association.

Aims:

The objective of this study was to identify the association between periodontal disease and OSA in adults with different comorbidities.

Settings and Design:

One hundred and ninety-nine individuals (107 women and 92 men) underwent polysomnography with a mean age of 49.9 years were recruited.

Materials and Methods:

The presence of OSA, comorbidities, and periodontal disease was evaluated in each individual. Student's t-tests or Chi-square and ANOVA tests were used to determine the differences between groups.

Results:

The prevalence of periodontal disease was 62.3% and 34.1% for gingivitis. The results showed no statistically significant association between all groups of patients with OSA and non-OSA patients for gingivitis (P = 0.27) and for periodontitis (P = 0.312). However, statistically significant association was shown between periodontitis and mild OSA compared with the periodontitis and non-OSA referent (P = 0.041; odds ratio: 1.37 and 95% confidence interval 1.11–2.68). The analysis between OSA and comorbidities showed a statistically significant difference for patients with OSA and hypertension (P < 0.001) and for patients with OSA and hypertensive cardiomyopathy (P < 0.001) compared with healthy individuals. Periodontitis was more likely in men with severe OSA and with any of two comorbidities such as hypertension or hypertensive cardiomyopathy. Women with hypertension or hypertensive cardiomyopathy were more likely to have mild OSA, and these associations were statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Conclusions:

This study identified association between periodontitis and mild OSA and this association was more frequent in women with hypertension or hypertensive cardiomyopathy. Periodontitis was associated with severe OSA in men who showed any of two comorbidities such as hypertension or hypertensive cardiomyopathy.

Key words: Comorbidities, obstructive sleep apnea, periodontal disease

INTRODUCTION

Periodontal disease is an infectious and chronic condition that leads to the destruction of the tissues supporting the tooth due to the accumulation of bacterial biofilm.[1] There are considerable variations in the prevalence of periodontitis between countries, but the risk of periodontitis increases in race of Africans and Hispanic.[1] Periodontal disease includes different periodontopathogens such as Porphyromonas gingivalis, Prevotella intermedia, Bacteroides forsythus, Fusobacterium nucleatum, Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, Capnocytophaga, Propionibacterium acnes, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa among others.[3] This microbiota triggers a local inflammation characterized by the infiltration of inflammatory cells such as polymorphonuclear cells, macrophages, lymphocytes, and plasma cells into the periodontal tissue that releases cytokines, interleukins, prostaglandins, and cell adhesion proteins.[4,5] The pathogenic microorganisms associated with periodontal disease enter the bloodstream, elevating the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin 1 (IL1) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα). These alterations appear to be the major mechanisms associated with the association between periodontitis and systemic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).[6,7,8]

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) defines OSA-hypopnea as a sleep disorder in which the complete (apnea) or partial (hypopnea) obstruction of the upper airway occurs.[9] The prevalence of OSA in the United States and Europe has been reported between 14% and 49% and between 19% and 26% in Colombia.[10,11] Transient and intermittent hypoxia in individuals with OSA promotes the transcription of TNFα and increases cytokine production, resulting in systemic inflammation.[12] In addition, inflammation, intermittent hypoxemia, and fragmented sleep observed in OSA have been suggested as risk factors for the development of cardio-cerebrovascular events, metabolic disease, and cognitive impairment.[13,14]

Some mechanisms that have been proposed to explain the relationship between periodontal disease as a risk factor for cardiovascular, metabolic, and other systemic diseases are (1) the risk factors shared between periodontal disease and systemic disease, (2) the presence of a subgingival bacterial biofilm as a source of Gram-negative bacteria, (3) the existence of the lesions' typical of periodontal disease, and (4) the periodontal pocket as a reservoir of inflammatory mediators.[15,16] However, OSA and periodontitis could be associated due to the fact that both diseases share same risk factors and due to inflammatory mediators are involved in the pathogenesis of OSA and periodontitis.[6] Although the association between OSA and periodontitis has been reported, the interactions between OSA severity and other comorbidities have been not established yet.[17]

The purpose of this study was to identify the association between periodontal disease and OSA in adults with different comorbidities.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Population and sample

The sample in this study included patients between 30 and 85 years of age who lived in Bogotá and attended the sleep clinic for a polysomnographic study. A convenience sample of 199 adults was obtained for this study. Patients who were selected underwent a polysomnographic study that was interpreted by a single professional according to the AASM criteria. Severity was classified according to the apnea–hypopnea index (AHI), with nonapnea defined as AHI <5, mild apnea as AHI = 5–14.9, moderate apnea as AHI = 15–29.9, and severe apnea as AHI >30. The Ethics Committees of the local faculty of dentistry and local clinic sleep approved this study. Once the patients agreed to participate in the study, informed consent was solicited and signed. Before the procedure at sleep clinic, a questionnaire was conducted that recorded the medical and pharmacological antecedents reported by the patient. History of systemic disease was based on a questionnaire completed by each patient, and it was compared with medicament ingest reported by each patient. The body mass index (BMI) of each patient was also measured and calculated. Parafunctional habits and smoking status in each patient were documented.

All patients selected at sleep clinic underwent intraoral clinical and periodontal examinations. Probing was performed on all teeth present in the mouth. The periodontal disease outcome measures included clinical attachment loss and periodontal pocket depth. Periodontal pocket was defined as the measurement up 4 mm from the gingival margin to the bottom of pocket. The gingival margin measurement was taken from the cementoenamel junction to the gingival margin. Three skilled examiners were calibrated for periodontal assessments so that measurements were comparable and similar. The calibrated examiners performed probing depth and gingival margin at six sites per tooth for each fully erupted tooth, except third molars, in each patient. The clinical attachment levels were calculated, and a periodontal diagnosis was provided based on the 1999 Armitage classification used to determine the severity of periodontitis based on insertion loss. Patients were classified into three groups after periodontitis assessment: healthy, gingivitis, and periodontitis.[18]

Statistical analyses

The descriptive statistics of basic demographic variables were calculated as means, medians, ranges, standard deviations, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The proportion of patients with or without OSA and periodontal and systemic diseases were determined. Student's t-tests (numerical variables) or Chi-square tests (proportions) were used to determine the differences between groups. Subsequently, ANOVA was performed to establish differences according to group. P < 0.05 was established as the significance threshold.

RESULTS

This study consisted of 199 individuals (107 women and 92 men) with a mean age of 49.9 years, of whom 53.8% were women with an average BMI = 27.6. Individuals were divided upon AHI, resulting in 58 individuals with nonapnea, 68 with mild OSA, 37 with moderate OSA, and 36 with severe OSA. The prevalence of comorbidities in this sample was 32% for arterial hypertension, 16.6% for hypertensive cardiomyopathy, 13.6% for coronary artery disease, 4.5% for diabetes, and 16.5% for hypothyroidism. A significant association was observed between OSA severity (P = 0.0001) and age, patients with severe and moderate OSA were 58 years and patients with mild OSA were 51 years on average, while patients without OSA were 40 years old on average.

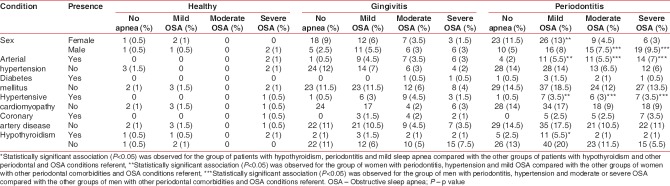

The prevalence of periodontal disease was 62.3% for periodontitis and 34.1% for gingivitis. The percentage of individuals who showed healthy periodontal status was 3.5%. The analysis to identify the periodontal condition based on the presence and severity of OSA showed no statistically significant association between all groups of patients with OSA and non-OSA patients for gingivitis (P = 0.27) and for periodontitis (P = 0.312). However, statistically significant association was shown between periodontitis and mild OSA compared with the periodontitis and non-OSA referent (P = 0.041; odds ratio: 1.37 and 95% CI: 1.11–2.68) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Periodontal condition based on the presence and severity of obstructive sleep apnea

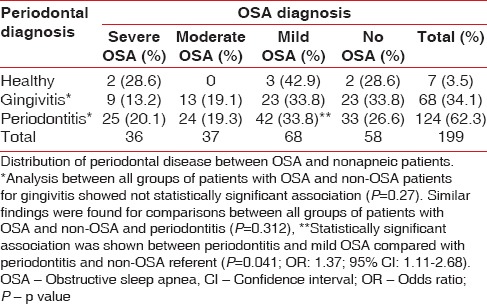

The analysis between OSA and comorbidities showed a statistically significant association for patients with OSA (severe, moderate, and mild) and hypertension compared with patients with hypertension and no apnea (P < 0.001). Similar results were found for patients with OSA and hypertensive cardiomyopathy compared with hypertensive cardiomyopathy and no OSA (P < 0.001). The frequencies of the systemic diseases associated with OSA are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Frequency of comorbidities according to obstructive sleep apnea diagnosis

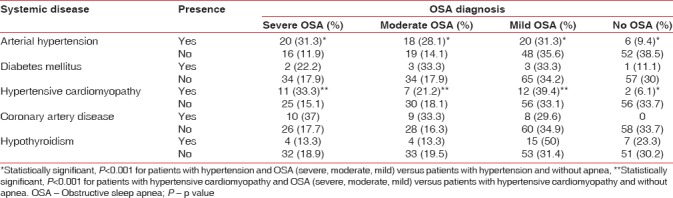

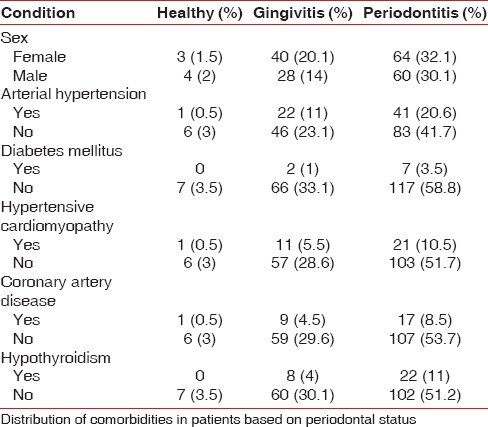

Systemic conditions were also evaluated based on the diagnosis of OSA and periodontal disease. This evaluation revealed that periodontitis is more likely in men with severe OSA and any of two comorbidities such as arterial hypertension or hypertensive cardiomyopathy. Women with arterial hypertension or hypertensive cardiomyopathy were more likely to have mild OSA and these associations were statistically significant [P < 0.05, Tables 3 and 4].

Table 3.

Periodontal diagnosis and systemic conditions

Table 4.

Frequency of comorbidities according to obstructive sleep apnea and periodontal diagnosis

DISCUSSION

The present study examined the relationship between OSA associated with different comorbidities and periodontal disease and found a statistically significant association between mild OSA and periodontitis (P < 0.05). These results coincide with previous findings reported by Sanders et al. (2015), who studied 12,469 in Hispanic community of Latinos between 18 and 74 years and found the higher prevalence of periodontitis in individuals with mild sleep disorder breathing. Other studies in different populations such as Korea, North American, and Taiwan have demonstrated a significant association between Severe OSA and periodontitis.[19,20,21,22] In contrast, Loke et al. did not find a significant association between OSA severity with the prevalence of periodontal disease severity categories.[23]

The relationship between periodontitis and OSA has not been elucidated. Al-Jewair et al. in a systematic review and meta-analysis found a statistically significant association between periodontal disease and OSA, but the causal-effect relationship between both diseases was debatable.[24] However, several theories have been proposed to explain bidirectional association between both diseases: (1) the dryness of the mucous membranes produced by oral respiration frequently observed in individuals with OSA (due to oral breathing or the pharmacological effects of hypotensive drugs), which enables the greater colonization of the periodontal microbiota; (2) the systemic inflammation that occurs in both OSA and periodontitis; (3) the oxidative stress that occurs in both diseases; and (4) the risk factors and comorbidities common to OSA and periodontitis.[6,25,26]

Our study investigated the relationship between periodontal disease and OSA associated with several comorbidities and the results showed that periodontitis was more frequent in men with severe or moderate OSA with any of two comorbidities such as arterial hypertension or hypertensive cardiomyopathy. Women with periodontitis showed statistically significant association with mild OSA and with any of these two comorbidities (arterial hypertension or hypertensive cardiomyopathy). The association between OSA and hypertension has been previously reported. More than 50% of people with OSA have hypertension, and OSA is one of the most common causes of secondary and refractory hypertension.[27] Systemic inflammation likely justifies the biological plausibility of the relationship between OSA and HTA in which hypoxia and the cyclic reoxygenation of OSA produce oxidative stress and activate the pro-inflammatory transcription factor, i.e., nuclear factor-kappa B, thereby stimulating the production of other systemic pro-inflammatory markers such as IL-8, TNFα, C-reactive protein, and intercellular and vascular cell adhesion molecules.[28,29] In addition, the relationship between arterial hypertension and periodontitis has been investigated, but the interpretation of results and identification of biological mechanisms that explain this relationship are difficult due to the heterogeneity of studies, the periodontal and hypertension diagnosis criteria, and the bacterial load and the inflammatory status at the moment of the clinical parameters' measurement.[30,31]

Hypertensive cardiomyopathy and coronary artery disease have been associated with OSA.[32,33] In our study, coronary artery disease was frequently associated with OSA, but this association was not statistically significant. In contrast, hypertensive cardiomyopathy showed statistically significant association in women and men with periodontitis. In our knowledge, there are not studies that report association between periodontitis and hypertensive cardiomyopathy until now, but arterial hypertension is the main risk factor for hypertensive cardiomyopathy;[34] therefore, although this association is biologically plausible, it is important to clarify in future studies if hypertensive cardiomyopathy is associated with OSA because this pathology and arterial hypertension are overlapping.

Hypothyroidism was also statistically associated with periodontitis and mild sleep apnea. Previous studies have been reported the association between OSA and hypothyroidism [35,36] and between hypothyroidism and periodontitis;[37,38] however, the physiopathology of these interrelationships has not been established and the association between hypothyroidism, periodontitis, and sleep apnea has not been previously documented. Diabetes mellitus was frequently observed in patients with OSA, but this association was not statistically significant.

Other risk factors common to OSA and periodontitis include male gender and advanced age.[2] Our study found a significant relationship between older men and the severity of OSA (P < 0.001). These findings coincide with those reported by Punjabi, who found that more than 50% of adults over 65 years old have some form of complaint related to a chronic sleep disorder.[39] However, the association between periodontal disease and OSA is weaker in older adults because, unlike periodontal disease (which increases with age), OSA decreases among the elderly.[40] Recently, the relationship between periodontitis and mild apnea was demonstrated for young adults (18–34 years) with greater significance compared with other age groups in Hispanic population residing in the US.[24] Our study did not verify this finding because our population was composed of adults older than 30 years, but we found that mild apnea was more frequently in women with periodontitis. Although this study is convenience sample, and for this reason is more difficult to generalize, it is important to investigate the role of the chronic intermittent hypoxia in the stimulation of bone remodeling like a protective mechanism to preserve bone density in elderly adults and the biological mechanisms involved in periodontitis and OSA in younger and older individuals.[41,42,43]

CONCLUSIONS

Our study demonstrated a significant association between Periodontitis and mild OSA and this association was more frequent in women with hypertension or hypertensive cardiomyopathy. In addition, periodontitis was associated with severe OSA in men who showed any of two comorbidities such as hypertension or hypertensive cardiomyopathy. This work suggests the need to perform routine dental evaluations and integral and multidisciplinary treatment for patients with OSA.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was funded by COLCIENCIAS through grant 369 Project 501953731808.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kornman KS, Page RC, Tonetti MS. The host response to the microbial challenge in periodontitis: Assembling the players. Periodontol 2000. 1997;14:33–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1997.tb00191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Löe H, Brown LJ. Early onset periodontitis in the United States of America. J Periodontol. 1991;62:608–16. doi: 10.1902/jop.1991.62.10.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haffajee AD, Socransky SS. Microbiology of periodontal diseases: Introduction. Periodontol 2000. 2005;38:9–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2005.00112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fujii R, Saito Y, Tokura Y, Nakagawa KI, Okuda K, Ishihara K, et al. Characterization of bacterial flora in persistent apical periodontitis lesions. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2009;24:502–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.2009.00534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arregoces FE, Uriza CL, Porras JV, Camargo MB, Morales AR. Relation between ultra-sensitive C-reactive protein, diabetes and periodontal disease in patients with and without myocardial infarction. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2014;58:362–8. doi: 10.1590/0004-2730000002899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gunaratnam K, Taylor B, Curtis B, Cistulli P. Obstructive sleep apnoea and periodontitis: A novel association? Sleep Breath. 2009;13:233–9. doi: 10.1007/s11325-008-0244-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khader YS, Albashaireh ZS, Alomari MA. Periodontal diseases and the risk of coronary heart and cerebrovascular diseases: A meta-analysis. J Periodontol. 2004;75:1046–53. doi: 10.1902/jop.2004.75.8.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Nardin E. The role of inflammatory and immunological mediators in periodontitis and cardiovascular disease. Ann Periodontol. 2001;6:30–40. doi: 10.1902/annals.2001.6.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sleep-related breathing disorders in adults: Recommendations for syndrome definition and measurement techniques in clinical research. The report of an American academy of sleep medicine task force. Sleep. 1999;22:667–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garvey JF, Pengo MF, Drakatos P, Kent BD. Epidemiological aspects of obstructive sleep apnea. J Thorac Dis. 2015;7:920–9. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.04.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruiz AJ, Sepúlveda MA, Martínez PH, Muñoz MC, Mendoza LO, Centanaro OP, et al. Prevalence of sleep complaints in colombia at different altitudes. Sleep Sci. 2016;9:100–5. doi: 10.1016/j.slsci.2016.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vgontzas AN, Papanicolaou DA, Bixler EO, Kales A, Tyson K, Chrousos GP, et al. Elevation of plasma cytokines in disorders of excessive daytime sleepiness: Role of sleep disturbance and obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:1313–6. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.5.3950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kendzerska T, Mollayeva T, Gershon AS, Leung RS, Hawker G, Tomlinson G, et al. Untreated obstructive sleep apnea and the risk for serious long-term adverse outcomes: A systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2014;18:49–59. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shamsuzzaman A, Amin RS, Calvin AD, Davison D, Somers VK. Severity of obstructive sleep apnea is associated with elevated plasma fibrinogen in otherwise healthy patients. Sleep Breath. 2014;18:761–6. doi: 10.1007/s11325-014-0938-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.How KY, Song KP, Chan KG. Porphyromonas gingivalis: An overview of periodontopathic pathogen below the gum line. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:53. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li X, Kolltveit KM, Tronstad L, Olsen I. Systemic diseases caused by oral infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13:547–58. doi: 10.1128/cmr.13.4.547-558.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gamsiz-Isik H, Kiyan E, Bingol Z, Baser U, Ademoglu E, Yalcin F, et al. Does obstructive sleep apnea increase the risk for periodontal disease? A Case-control study. J Periodontol. 2017;88:443–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.2016.160365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Armitage GC. Periodontal diagnoses and classification of periodontal diseases. Periodontol 2000. 2004;34:9–21. doi: 10.1046/j.0906-6713.2002.003421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seo WH, Cho ER, Thomas RJ, An SY, Ryu JJ, Kim H, et al. The association between periodontitis and obstructive sleep apnea: A preliminary study. J Periodontal Res. 2013;48:500–6. doi: 10.1111/jre.12032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahmad NE, Sanders AE, Sheats R, Brame JL, Essick GK. Obstructive sleep apnea in association with periodontitis: A case-control study. J Dent Hyg. 2013;87:188–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keller JJ, Wu CS, Chen YH, Lin HC. Association between obstructive sleep apnoea and chronic periodontitis: A population-based study. J Clin Periodontol. 2013;40:111–7. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanders AE, Essick GK, Beck JD, Cai J, Beaver S, Finlayson TL, et al. Periodontitis and sleep disordered breathing in the Hispanic community health study/Study of Latinos. Sleep. 2015;38:1195–203. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loke W, Girvan T, Ingmundson P, Verrett R, Schoolfield J, Mealey BL, et al. Investigating the association between obstructive sleep apnea and periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2015;86:232–43. doi: 10.1902/jop.2014.140229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Al-Jewair TS, Al-Jasser R, Almas K. Periodontitis and obstructive sleep apnea's bidirectional relationship: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Breath. 2015;19:1111–20. doi: 10.1007/s11325-015-1160-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lavie L, Lavie P. Molecular mechanisms of cardiovascular disease in OSAHS: The oxidative stress link. Eur Respir J. 2009;33:1467–84. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00086608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fitzsimmons TR, Sanders AE, Bartold PM, Slade GD. Local and systemic biomarkers in gingival crevicular fluid increase odds of periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2010;37:30–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2009.01506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rimoldi SF, Scherrer U, Messerli FH. Secondary arterial hypertension: When, who, and how to screen? Eur Heart J. 2014;35:1245–54. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Natsios G, Pastaka C, Vavougios G, Zarogiannis SG, Tsolaki V, Dimoulis A, et al. Age, body mass index, and daytime and nocturnal hypoxia as predictors of hypertension in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2016;18:146–52. doi: 10.1111/jch.12645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baguet JP, Hammer L, Lévy P, Pierre H, Rossini E, Mouret S, et al. Night-time and diastolic hypertension are common and underestimated conditions in newly diagnosed apnoeic patients. J Hypertens. 2005;23:521–7. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000160207.58781.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martin-Cabezas R, Seelam N, Petit C, Agossa K, Gaertner S, Tenenbaum H, et al. Association between periodontitis and arterial hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am Heart J. 2016;180:98–112. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2016.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsioufis C, Kasiakogias A, Thomopoulos C, Stefanadis C. Periodontitis and blood pressure: The concept of dental hypertension. Atherosclerosis. 2011;219:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eleid MF, Konecny T, Orban M, Sengupta PP, Somers VK, Parish JM, et al. High prevalence of abnormal nocturnal oximetry in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1805–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baguet JP, Barone-Rochette G, Tamisier R, Levy P, Pépin JL. Mechanisms of cardiac dysfunction in obstructive sleep apnea. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2012;9:679–88. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2012.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kai H, Kudo H, Takayama N, Yasuoka S, Aoki Y, Imaizumi T, et al. Molecular mechanism of aggravation of hypertensive organ damages by short-term blood pressure variability. Curr Hypertens Rev. 2014;10:125–33. doi: 10.2174/1573402111666141217112655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuczyński W, Gabryelska A, Mokros Ł, Białasiewicz P. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and hypothyroidism – Merely concurrence or causal association? Pneumonol Alergol Pol. 2016;84:302–6. doi: 10.5603/PiAP.2016.0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang M, Zhang W, Tan J, Zhao M, Zhang Q, Lei P, et al. Role of hypothyroidism in obstructive sleep apnea: A meta-analysis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32:1059–64. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2016.1157461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elangovan S, Nalliah R, Allareddy V, Karimbux NY, Allareddy V. Outcomes in patients visiting hospital emergency departments in the United States because of periodontal conditions. J Periodontol. 2011;82:809–19. doi: 10.1902/jop.2010.100228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yussif NM, El-Mahdi FM, Wagih R. Hypothyrodism as a risk factor of periodontitis and its relation with Vitamin D deficiency: Mini-review of literature and a case report. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab. 2017;14:312–6. doi: 10.11138/ccmbm/2017.14.3.312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Punjabi NM. The epidemiology of adult obstructive sleep apnea. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5:136–43. doi: 10.1513/pats.200709-155MG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Launois SH, Pépin JL, Lévy P. Sleep apnea in the elderly: A specific entity? Sleep Med Rev. 2007;11:87–97. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mizutani S, Ekuni D, Tomofuji T, Azuma T, Kataoka K, Yamane M, et al. Relationship between xerostomia and gingival condition in young adults. J Periodontal Res. 2015;50:74–9. doi: 10.1111/jre.12183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bixler EO, Vgontzas AN, Ten Have T, Tyson K, Kales A. Effects of age on sleep apnea in men: I. Prevalence and severity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:144–8. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.1.9706079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sforza E, Thomas T, Barthélémy JC, Collet P, Roche F. Obstructive sleep apnea is associated with preserved bone mineral density in healthy elderly subjects. Sleep. 2013;36:1509–15. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]