Abstract

Background:

This study was aimed to compare the efficacy and soft tissue wound healing using diode lasers (810 nm) versus conventional scalpel approach as uncovering technique during the second-stage surgery in implants. This was a prospective, randomized study which was conducted on 20 subjects in which the implants were already placed using a two-stage technique. Implant sites were examined and the patients were randomly divided into two groups.

Materials and Methods:

Patients were randomly divided into two groups, i.e., Group A and Group B. In Group A, implants were uncovered as a part of Stage II surgery with conventional scalpel technique, and in Group B, implants were uncovered using 810 nm diode laser. Clinical parameters such as need and amount of local anesthesia, duration of surgery, intraoperative bleeding, pain index, wound healing index (HI), and time for impression taking were recorded at various intervals.

Results:

Statistical differences for clinical parameters were seen between Group A and Group B showing uncovery of implant with laser more effective, and for time of impression taking, difference was statistically significant showing that impressions were taken early in case of Group A because of better healing which was recorded with help of HI, but the difference in time of healing between Group A and Group B was not statistically significant.

Conclusion:

The use of a diode laser (810 nm) in the second-stage implant surgery can minimize surgical trauma, reduce the amount of anesthesia, improve visibility during surgery due to the absence of bleeding, and eliminate postoperative discomfort.

Key words: Dental implants, diode laser, implant exposure, second-stage surgery

INTRODUCTION

Parallelism in the expansion of implant and laser dentistry are the same as for any other soft tissue dental procedures. Surgical lasers have been used with good results in a variety of ways in implantology, ranging from placement to second-stage surgery for exposure of the buried implant. Laser-assisted technique achieves same results as the traditional technique but with shorter timing, micro-invasiveness, and better patient compliance.

Lasers have beneficial properties over conventional scalpel that includes hemostasis, reduced mechanical trauma, and less operative and postoperative pain.[1,2] Lasers which are used primarily for soft tissue treatments are carbon dioxide (CO2), neodymium: yttrium aluminum garnet (Nd:YAG) and diode lasers. Other lasers such as erbium: YAG (Er:YAG) and erbium, chromium: YSGG (Er, Cr:YSGG) lasers can also be used for both soft and hard tissue applications.[3] These days, diode lasers are being widely used as a tool for gingival soft tissue procedures such as gingivectomy, frenectomy, and gingivoplasty, deepithelialization of periodontal pocket, and gingival depigmentation. Along with that, it has also being widely used in the second-stage surgery of dental implants, irradiation of apthous ulcers, and soft tissue crown lengthening.[4]

Diode lasers are primarily used by contact application when cutting or coagulation is required.[5] The tip of the diode laser can be used either in an initiated state or in uninitiated state. In initiated state, the tip has been coated with a blocking material, which converts the light energy into heat by refraction. This conversion of energy creates hot tip, which ultimately leads to cell ablation and results in cutting of tissue.[6] On other hand, an uninitiated diode tip is useful for bacterial decontamination either on the implants surface or within the periodontal sulcus/pocket.[6]

The diode laser has shown to have similar properties as the Nd:YAG laser that emits a very similar wavelength, but Nd:YAG leads to a marked increase in temperature in deeper tissue layers. On the other hand, tissue penetration of a diode laser is less, but rate of heat generation is higher. Since the diode laser causes minimal damage to the periosteum and bone and able to remove a thin layer of epithelium cleanly,[7] it can be used for a variety of soft tissue procedures without impacting the neighboring tissues.

In a study on the use of the diode laser to uncover dental implants, Yeh et al. concluded that the soft tissue diode laser offers an alternative technique for uncovering dental implants and that the technique provides an efficient, safe, and patient-friendly method for the performance of the second-stage implant surgery, allowing a faster rehabilitation phase.[8]

El-Kholey also conducted a study and concluded that the use of a diode laser in the second-stage implant surgery can minimize surgical trauma, eliminate the need for anesthesia, improve visibility during surgery due to the absence of bleeding, and eliminate postoperative discomfort. The time needed for tissue healing is short, which results in a shorter time for rehabilitation of the patient. The only limitation to the use of this technique is a lack of sufficient keratinized tissues around the implant.[9]

Hence, the present study was undertaken to compare the clinical outcomes associated with the traditional cold scalpel surgery versus use of diode laser in the second-stage surgery in implants. This study was designed to assess if dental implant uncovering is possible with a diode laser without anesthesia versus traditional cold scalpel surgery by undertaking certain parameters for evaluation in both cases which were compared at selected time intervals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

For this comparative study, participants were selected from the outpatient department, who had already got implants placed in the department. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the ethical committee of the institution. Each patient was given a detailed verbal and written description of the study, and all the selected patients were required to sign an informed consent form before the commencement of the study. Patients aged from 18 to 60 years of both the gender with the presence of adequate healthy keratinized tissue surrounding the implant site were included in the study. Only well-motivated and cooperative patients and those who were willing to provide informed consent were included. Patients with inflammation at implant site, exposed implant site, lack of osseointegration as evident radiographically, and infection at implant site, uncooperative patients, and medically compromised patients were excluded.

The patients were clearly explained study protocols and procedure in detail, and duly signed written consent was taken from them. In this study, 20 patients in whom the implants were already placed using a two-stage technique were selected. Implant sites were examined and the patients were randomly divided into two groups.

Group A: In this group, implants were uncovered as part of stage II surgery with conventional scalpel technique

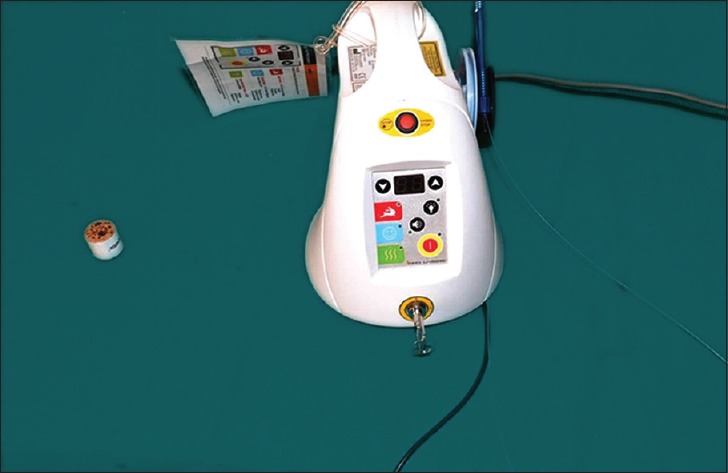

Group B: In this group, implants were uncovered as part of stage II surgery using 810 nm diode laser [Figure 1]. The laser used in this study was 810 nm diode laser at continuous mode with power of 1.5 Watts.

Figure 1.

Diode laser

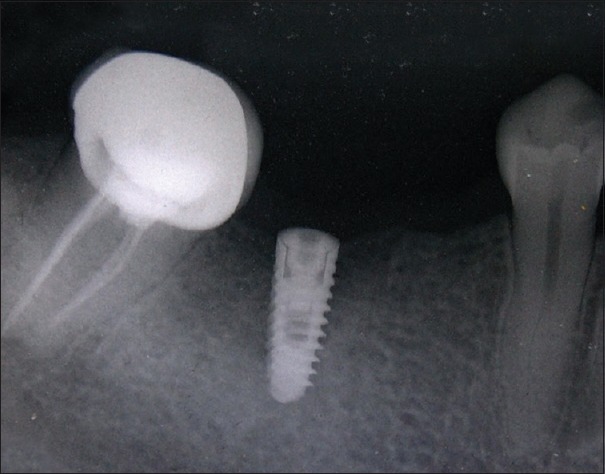

After evaluation of preclinical records and obtaining adequate local anesthesia (LA), in Group A, circular-shaped incision of diameter approximately 2–3 mm was given on the soft tissue present on top of the implant head with 15 No. blade, and small circular area of the tissues less than the size of the implant was excised to precisely determine the site of the implant. After the determination of exact location of the implant, the circular incision was widened to completely uncover the implant; then, the healing abutment was attached [Figures 2–5].

Figure 2.

Preoperative intraoral periapical radiograph (Group A)

Figure 5.

Placement of healing cap (Group A)

Figure 3.

Presurgical site (Group A)

Figure 4.

Circular-shaped incision (Group A)

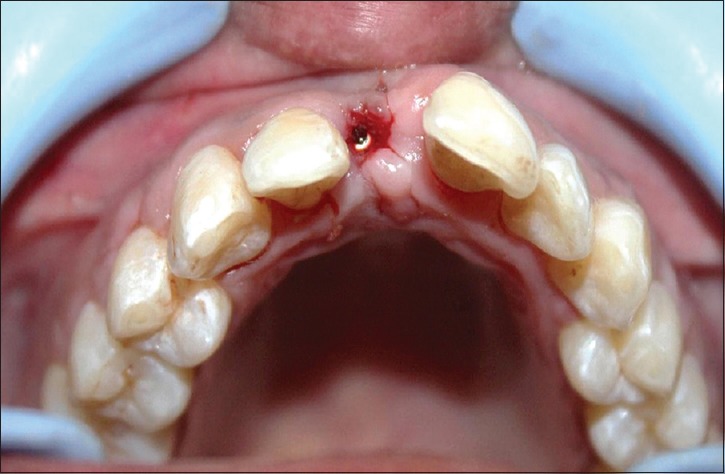

In Group B, the second-stage surgery was done using an 810 nm diode laser and the laser was used to create a small opening, which was increased until any part of the cover screw appears. Next, ablation of the tissue over the implant was performed until the surgical opening became just large enough to allow removal of the cover screw. After this step, the cover screw of the implant was removed, and then, healing abutment was attached [Figures 6–9].

Figure 6.

Preoperative intraoral periapical radiograph (Group B)

Figure 9.

Placement of healing cap (Group B)

Figure 7.

Presurgical site (Group B)

Figure 8.

Removal of mucosa covering implant with laser (Group B)

Postoperatively, no patients in either group were prescribed antibiotics. For analgesia, ibuprofen 400 mg + paracetamol 325 mg was prescribed on need basis.

Patients were recalled after 24 h of surgery, then at 48 h, and then again at 72 h for assessment and recording of pain with the help of visual analog scale (VAS).[10] Furthermore, patients were asked to mark the readings of pain on VAS before intake of analgesic if they feel the need of taking analgesic. For the evaluation of healing, patients were recalled on the 7th day after surgery and healing was estimated with the help of HI,[11] and after that, impressions were taken on the basis of HI for various subjects [Figures 10 and 11].

Figure 10.

Postoperative healing on the 7th day (Group A)

Figure 11.

Postoperative healing on the 7th day (Group B)

The following clinical parameters were recorded during the surgery, at the end of surgery, and further at various intervals:

Need and amount of LA: In both groups, the need for LA and its amount used during surgery (in ml) was noted before surgery

Duration of surgery: The duration of the stage II surgery in both groups was noted in minutes after completion of surgery

Intraoperative bleeding: Intraoperative bleeding was rated by the surgeon on a three-point category rating scale (1 = minimal bleeding; 2 = normal bleeding; 3 = excessive bleeding)[9]

Pain index: Subjects pain levels were measured by VAS for pain.[10] It consists of readings from 0 to 10. Zero is for no pain and ten is for maximum pain

Wound HI: Clinical evaluation of healing event was estimated with recordings of HI.[11] Recordings of HI were performed on the 7th-day postsurgery

Time of impression taking: Time of impression, i. e., after how many days of the 2nd stage surgery, impressions could be taken for prosthesis was noted.

RESULTS

In both groups, a clinical assessment of the parameters was made during the surgery, at the end of surgery, and further at various intervals to evaluate the healing status and the possibility of taking an impression for prosthesis. The results were compiled and statistically analyzed using (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.)SPSS 21 Version.

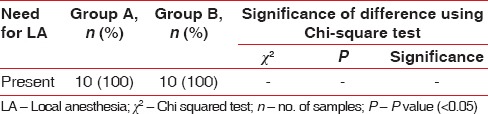

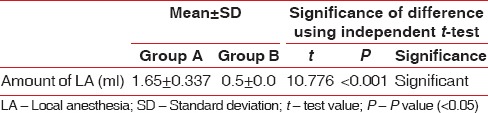

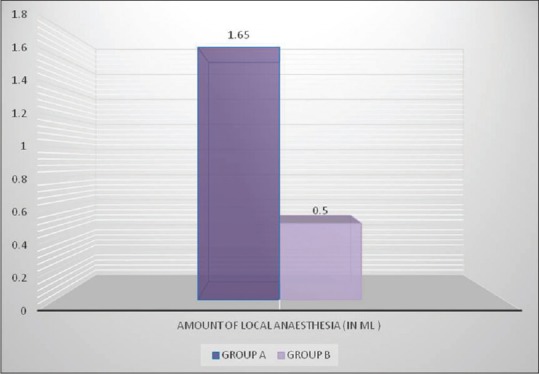

Need for LA was 100% that is LA was needed in all the subjects and mean of amount of LA needed for Group A was found to be 1.65 ± 0.337 ml and for Group B was found to be 0.5 ± 0.0 ml. Comparison of need for LA among Group A and B was done using Chi-square test, and no difference was seen in both groups as the LA was needed in all the subjects of Group A and Group B. For comparison of amount of LA between Group A and Group B, independent “t” test was used and the mean difference between Group A and Group B was found to be 1.15 ± 0.106 ml which was statistically significant P < 0.05 [Tables 1, 2 and Figures 12, 13].

Table 1.

Intergroup comparison of need for local anesthesia in Group A and Group B

Table 2.

Intergroup comparison of amount of local anesthesia (ml) between the Group A and Group B

Figure 12.

Intergroup comparison of need for local anesthesia (%)

Figure 13.

Intergroup comparison of amount of local anesthesia

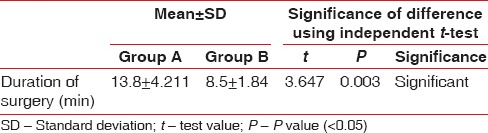

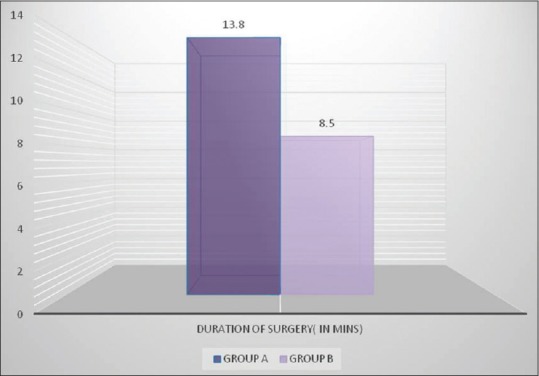

Duration of the surgery was observed in minutes, and the mean duration for Group A was found to be 13.8 ± 4.211 min and for Group B was found to be 8.5 ± 1.84 min. For the comparison of duration of surgery among Group A and Group B, independent t-test was used and the mean difference between Group A and Group B was found to be 5.3 ± 1.4 min which was statistically significant at P < 0.05 [Table 3 and Figure 14].

Table 3.

Intergroup comparison of duration of surgery (min) between the Group A and Group B

Figure 14.

Intergroup comparison of duration of surgery

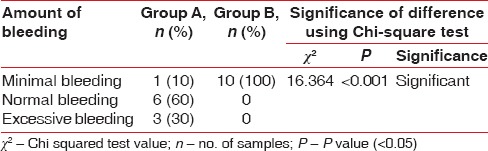

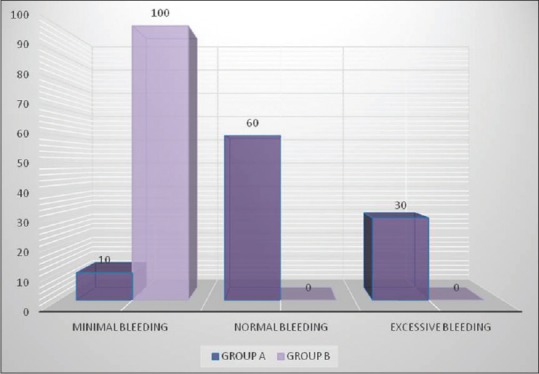

Intraoperative bleeding was observed as minimal in 10% of cases, normal in 60% of cases, and excessive bleeding in 30% cases of Group A and was observed as minimal in 100% cases of Group B. Intergroup comparison of intraoperative bleeding among Group A and B was done using Chi-square test. When bleeding score was compared between groups, minimal bleeding, normal bleeding, and excessive bleeding were observed in 1 (10%), 6 (60%), and 3 (30%) cases of Group A, whereas all the cases of Group B observed minimal bleeding. Chi-square value was 16.36 and P < 0.05 making the difference between Group A and Group B statistically significant [Table 4 and Figure 15].

Table 4.

Intergroup comparison of amount of intraoperative bleeding in Group A and Group B

Figure 15.

Intergroup comparison of amount of intraoperative bleeding

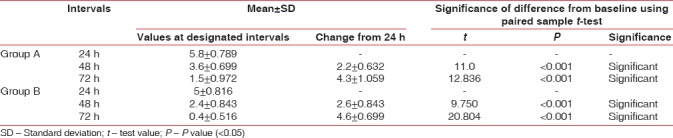

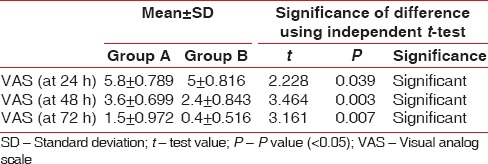

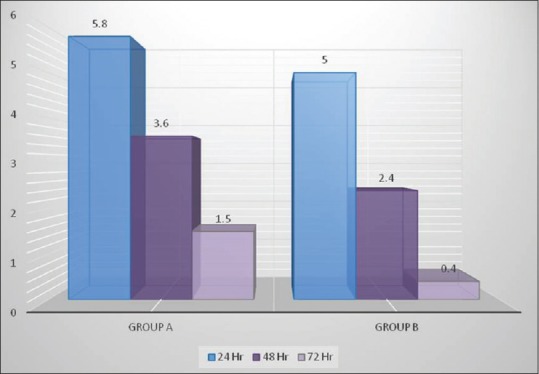

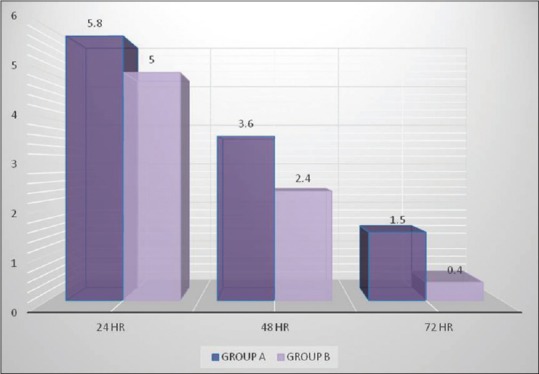

The mean pain index scores at the 24 h interval for the Group A and Group B was 5.8 ± 0.789 and 5 ± 0.816. The difference between the groups (at 24 h) analyzed using independent t-test was statistically significant (P < 0.05). At the 48-h interval, Group A had pain score of 3.6 ± 0.699 and 2.4 ± 0.843 for the Group B, and at the 72-h interval, mean pain index score for Group A and Group B was 1.5 ± 0.972 and 0.4 ± 0, respectively. The difference between the groups at 48-h and 72-h interval was also statistically significant at “ < 0.05 [Tables 5, 6 and Figures 16, 17].

Table 5.

Intragroup comparison of pain index scores (visual analog scale) between 3 Intervals: 24, 48 and 72 h

Table 6.

Intergroup comparison of visual analog scale (24, 48, 72 h) between the Group A and Group B

Figure 16.

Intragroup comparison of visual analog scale score

Figure 17.

Intergroup comparison of visual analog scale score

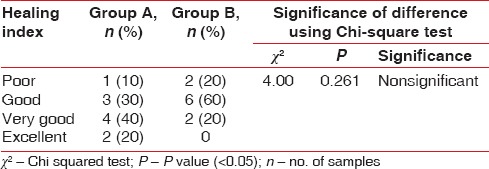

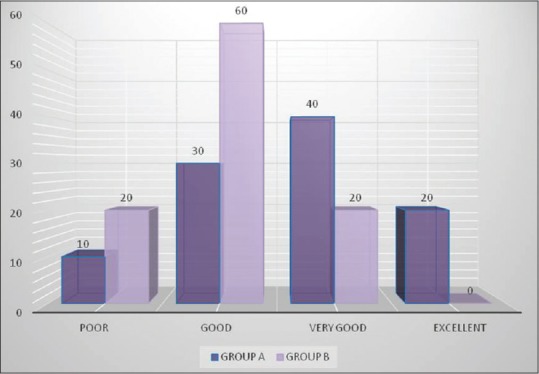

Intergroup comparison of HI among Group A and B was done using Chi-square test. P value was 0.26 which is more than 0.05, making difference between Group A and Group B nonsignificant among different HI categories, i.e., poor (Group A = 10%, Group B = 20%), good (Group A = 30%, Group B = 60%), very good (Group A = 40, Group B = 20), and excellent (Group A = 20, Group B = 0) category [Table 7 and Figure 18].

Table 7.

Intergroup comparison of healing index in Group A and Group B

Figure 18.

Intergroup comparison of healing index

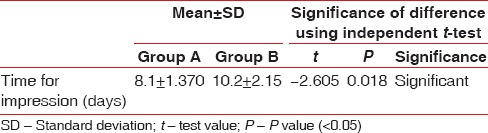

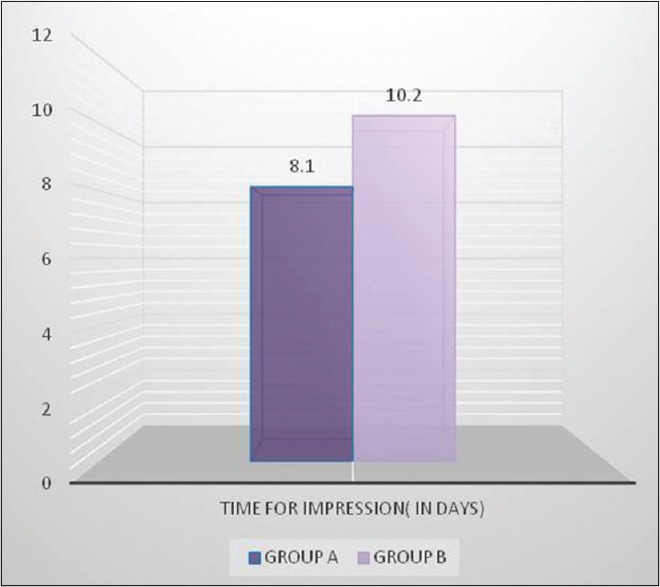

Comparison of time for impression between the Group A and Group B was done using independent t-test. The time for impression taking in Group A and B was found to be 8.1 ± 1.370 and 10.2 ± 2.15 days, respectively. The mean difference between both groups was found to be − 2.1 ± 0.806, and the P value was 0.018, i.e., P < 0.05, making the results statistically significant [Table 8 and Figure 19].

Table 8.

Intergroup comparison of time for impression (days) between the Group A and Group B

Figure 19.

Intergroup comparison of time for impression

DISCUSSION

Scalpels have been used for many years because of their ease of use, but the application of a surgical laser to the soft tissues surrounding or covering the implant offers a series of potential advantages. It also improves healing and shortens the time needed before taking the impression.[9] In the present study, the results obtained in the laser-treated patients agree with trials and studies done with the diode or other laser systems to uncover implants.[8,12,13,14,15]

During comparison of need for LA among Group A and Group B, no difference was seen in both the groups as the LA was needed in all patients of Group A and Group B. Mean of amount of LA needed for Group A was more than Group B and the difference between both groups were statistically significant showing the amount of LA was more in control group (Group A). These observations were in accordance with the study of Shalawe et al.[16] and El-Kholey,[9] who observed mean volume of LA used was more in Group A (scalpel).

Mean duration of surgery among Group A and Group B was found to be statistically significant showing duration of surgery was more in scalpel (Group A) patients. When bleeding score was compared between groups, in most of the cases, Group A observed normal bleeding whereas all the cases of Group B observed minimal bleeding, making the difference between Group A and Group B statistically significant. Similar results were obtained by El-Kholey [9] showing minimal bleeding in cases done with laser and normal bleeding in cases with conventional scalpel technique. There was statistically less pain experienced by patients following the laser-assisted surgical procedure. This is in accordance with other studies. We found that use of the 810 nm diode laser during surgical procedure resulted in less postoperative pain than the control group, with difference reaching statistical significance. This finding suggests that laser (810 nm) application may be more beneficial in procedures where postoperative pain is expected by the patient or the practitioner.

On comparison of healing in both groups, group A shows better healing results than group B. However, the results were not statistically significant and also very few data are available for histology of healing after laser treatment. A study done by Jin et al.[17] revealed that lower level of transforming growth factor-beta 1 expression was observed for scalpel wounds compared to laser wounds, which was due to lower damage caused by scalpel when compared to laser leading to delayed healing.

This study must be interpreted with consideration to the following limitations:

First, a larger sample size of the study would have anticipated more definitive conclusions. A second limitation is lack of histological examination for better healing assessment which was beyond the scope of this study and the third was lack of blindness by clinical examiner.

Overall, the results of this study suggest that that the use of a diode laser (810 nm) in second-stage implant surgery can minimize surgical trauma, reduce the amount of anesthesia, improve visibility during surgery due to the absence of bleeding, and eliminate postoperative discomfort. The only limitation to the use of this technique is a lack of sufficient keratinized tissues around the implant.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aoki A, Mizutani K, Takasaki AA, Sasaki KM, Nagai S, Schwarz F, et al. Current status of clinical laser applications in periodontal therapy. Gen Dent. 2008;56:674–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coleton S. Lasers in surgical periodontics and oral medicine. Dent Clin North Am. 2004;48:937, vii–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldstep F. Diode Lasers for Periodontal Treatment: The Story So Far. Oral Health Magazine. 2009;12:44–6. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moritz A, Schoop U, Goharkhay K, Schauer P, Doertbudak O, Wernisch J, et al. Treatment of periodontal pockets with a diode laser. Lasers Surg Med. 1998;22:302–11. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9101(1998)22:5<302::aid-lsm7>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aoki A, Mizutani K, Schwarz F, Sculean A, Yukna RA, Takasaki AA, et al. Periodontal and peri-implant wound healing following laser therapy. Periodontol 2000. 2015;68:217–69. doi: 10.1111/prd.12080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pang P, Andreana S, Aoki A. Laser energy in oral soft tissue applications. J Laser Dent. 2010;18:123–31. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prabhuji ML, Madhupreetha S, Archana V. Treatment of gingival hyperpigmentation for aesthetic purposes using the diode laser. Int Mag Laser Dent. 2011;3:18–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yeh S, Jain K, Andreana S. Using a diode laser to uncover dental implants in second-stage surgery. Gen Dent. 2005;53:414–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El-Kholey KE. Efficacy and safety of a diode laser in second-stage implant surgery: A comparative study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;43:633–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Breivik H, Borchgrevink PC, Allen SM, Rosseland LA, Romundstad L, Hals EK, et al. Assessment of pain. Br J Anaesth. 2008;101:17–24. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Landry RG, Turnbull RS, Howley T. Effectiveness of benzydamine HCl in the treatment of periodontal postsurgical patients. Res Clin Forum. 1988;10:105–18. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller RJ. Lasers in oral implantology. Dental Pract. 2006:112–4. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gianfranco S, Francesco SE, Paul RJ. Erbium and diode lasers for operculisation in the second phase of implant surgery: A case series. Timisoara Med J. 2010;60:117–23. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arnabat-Domínguez J, España-Tost AJ, Berini-Aytés L, Gay-Escoda C. Erbium: YAG laser application in the second phase of implant surgery: A pilot study in 20 patients. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2003;18:104–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arnabat-Domínguez J, Bragado-Novel M, España-Tost AJ, Berini-Aytés L, Gay-Escoda C. Advantages and esthetic results of erbium, chromium: yttrium-scandium-gallium-garnet laser application in second-stage implant surgery in patients with insufficient gingival attachment: A report of three cases. Lasers Med Sci. 2010;25:459–64. doi: 10.1007/s10103-009-0728-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shalawe W, Ibrahim Z, Sulaiman A. Clinical comparison between diode laser and scalpel incisions in oral soft tissue biopsy. Al Rafidain Dent J. 2012;12:337–43. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jin JY, Lee SH, Yoon HJ. A comparative study of wound healing following incision with a scalpel, diode laser or Er, Cr: YSGG laser in guinea pig oral mucosa: A histological and immunohistochemical analysis. Acta Odontol Scand. 2010;68:232–8. doi: 10.3109/00016357.2010.492356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]