Abstract

Objectives

To determine the frequency of missed opportunities (MOs) among patients newly diagnosed with HIV, risk factors for presenting MOs and the association between MOs and late presentation (LP) to care.

Design

Retrospective analysis.

Setting

HIV outpatient clinic at a Swiss tertiary hospital.

Participants

Patients aged ≥18 years newly presenting for HIV care between 2010 and 2015.

Measures

Number of medical visits, up to 5 years preceding HIV diagnosis, at which HIV testing had been indicated, according to Swiss HIV testing recommendations. A visit at which testing was indicated but not performed was considered an MO for HIV testing.

Results

Complete records were available for all 201 new patients of whom 51% were male and 33% from sub-Saharan Africa. Thirty patients (15%) presented with acute HIV infection while 119 patients (59%) were LPs (CD4 counts <350 cells/mm3 at diagnosis). Ninety-four patients (47%) had presented at least one MO, of whom 44 (47%) had multiple MOs. MOs were more frequent among individuals from sub-Saharan Africa, men who have sex with men and patients under follow-up for chronic disease. MOs were less frequent in LPs than non-LPs (42.5% vs 57.5%, p=0.03).

Conclusions

At our centre, 47% of patients presented at least one MO. While our LP rate was higher than the national figure of 49.8%, LPs were less likely to experience MOs, suggesting that these patients were diagnosed late through presenting late, rather than through being failed by our hospital. We conclude that, in addition to optimising provider-initiated testing, access to testing must be improved among patients who are unaware that they are at HIV risk and who do not seek healthcare.

Keywords: missed opportunities, Hiv diagnosis, Hiv testing, Hiv indicator conditions, late presenters

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We defined the term, ‘missed opportunities’, currently lacking a consensus definition, based on the Swiss HIV testing recommendations applicable to our institution.

A centralised database enabled us to examine all patient episodes at our centre, to determine the number and type of missed opportunities.

We used multivariate logistic regression to show a robust association between patient characteristics and the risk of missed opportunities for HIV testing.

As with any monocentric study, our findings may not be applicable to all centres in Switzerland, due to differences in hospital structure and local patient population.

Introduction

Late presentation (LP) to care among people living with HIV prolongs the period between seroconversion and treatment, and leads to an avoidable increase in morbidity, mortality, healthcare costs and risk of onward transmission.1 In Europe, even in countries with adequate healthcare provision and HIV testing recommendations, LPs make up to half of all new HIV diagnoses.2 In Switzerland, while 81% of adults living with HIV in 2012 were estimated to be diagnosed,3 49.8% of patients diagnosed and enrolled in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study between 2009 and 2012 were LPs, with CD4 counts below 350 cells/mm3 and/or an AIDS-defining illness at presentation.4

To maximise early HIV diagnosis, HIV testing recommendations have been published by the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health since 2007 and updated three times.5–8 In 2007, the recommendations introduced physician-initiated counselling and testing (PICT), proposing targeted testing and describing HIV testing indications in the text.5 In 2010, testing indications were mentioned in the text and presented as tables.6 Although the term HIV-associated indicator conditions (HIV ICs) was not in general use at this time, HIV ICs were included in the 2010 recommendations. In 2013, the recommendations highlighted HIV ICs and introduced HIV screening of patients commencing immunosuppressive therapy.7 It also became medically indefensible to not propose HIV testing to a patient presenting testing indications. In 2015, the content of the recommendations remained similar, but the table of symptoms and signs of acute HIV infection was presented first to emphasise this clinical presentation as an indication for HIV testing.8 In summary, apart from the addition of screening of patients commencing immunosuppressive therapy in 2013, the recommendation updates between 2010 and 2015 involved changes in format but not overall content.

The Swiss healthcare system is based on compulsory individual health insurance coverage, which is regulated at a federal level. It is estimated that >98% of the population has coverage, and access to care is excellent.9 For vulnerable populations, including undocumented migrants, healthcare is provided through cantonal social services which cover health insurance charges, although not all individuals may be aware of this. We have observed that some vulnerable populations, for example, sex workers, use the emergency department (ED) as a primary healthcare facility10 and that fewer than 90% of patients presenting to the ED have a primary care physician.11 Further, Switzerland has among the highest out-of-pocket costs in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.9 While HIV testing is covered under basic health insurance, costs can be attributed directly to the patient according to their specific health insurance package or if testing is performed on the demand of the patient, rather than on the recommendation of a physician.

When an individual presents to a healthcare provider with indications for HIV testing but is not offered a test, this constitutes a missed opportunity (MO) for HIV testing, regardless of his/her serostatus.1 In 2016, several studies were published on MOs in Europe12–15 and Israel16 (online supplementary table S1). These studies covered a period of 4–7 years between 2007 and 2015 and reported MO rates of 14.5%–34%.15 13 Many highlighted the importance of physician awareness of testing indications in reducing MOs.12 15 16 While the Swiss PICT recommendations, by definition, emphasise the responsibility of the physician in proposing HIV testing, we have observed that, for example, only 18% of ED doctors in French-speaking Switzerland were aware of the 2010 Swiss Federal Office of Public Health recommendations and that, even if aware, they did not adhere to them.17 In the ED and other services at our centre, these recommendations made no difference to HIV testing rates.18

bmjopen-2017-019806supp001.pdf (56.1KB, pdf)

The aims of this study were therefore to determine the frequency of MOs among newly diagnosed patients presenting for care at our outpatient HIV service, and patient risk factors for presenting MOs, and to determine the association between MOs and LP to care.

Methods

Due to the retrospective design, the requirement of patient informed consent was waived.

Patient and public involvement statement

The study being retrospective, patients or the public were not involved in the design or in the conduct of the study.

Study setting

The study was conducted at Lausanne University Hospital, a 1500-bed teaching hospital which serves as a primary-level community hospital for Lausanne (catchment population 300 000) and as a secondary and tertiary referral hospital for Western Switzerland (catchment population 1–1.5 million). HIV seroprevalence in the region is estimated to be 0.2%–0.5%.3 19 At Lausanne University Hospital, medical records are electronic and include all hospital visits, discharge summaries (inpatients), clinical letters (outpatients) and laboratory reports.

In Switzerland, health insurance is mandatory. While most patients have a primary care physician, individuals may visit a specialist without referral. Outpatient HIV care at Lausanne University Hospital is provided by the infectious diseases service. All patients are invited to be enrolled in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study, a national prospective cohort study with ongoing enrolment since 1988.20

Definitions

LP was defined as presenting for care with chronic HIV infection with a CD4 count <350 cells/mm3, in accordance with the European consensus working group definition.21

Acute HIV infection was defined as a positive blood HIV-RNA assay or a positive p24 antigen assay with an incomplete Western blot.22

The term MO for HIV testing has no consensus definition. For this study, a MO was defined as a visit to Lausanne University Hospital at which HIV testing was indicated but not performed, regardless of the serostatus of the patient. Testing was considered as indicated according to five broad indications, based on the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health 2015 recommendations8 but present in the recommendations from 2010 onwards: signs and symptoms of acute HIV infection; AIDS-defining illness; HIV ICs8 (such as herpes zoster, ongoing mononucleosis-like illness or unexplained thrombocytopenia)23 24; situations in which HIV infection should be excluded (eg, planned immunosuppressive treatment and pregnancy) and epidemiological risk (belonging to or having a sexual partner from a high-risk group: men who have sex with men (MSM), people who inject drugs (PWIDs) and individuals originating from a high-prevalence region, notably, sub-Saharan Africa).8

Since 2013, when it became a legal responsibility for the physician to propose HIV testing when indicated,7 any test offered but refused by the patient has been documented in the medical notes. The situation in which HIV testing was documented as indicated and proposed, but declined by the patient, was therefore not considered as a MO.

Study design

The study retrospectively analysed all patients with newly diagnosed HIV presenting to the Lausanne University Hospital infectious diseases outpatient clinic from 1 January 2010 to 31 December 2015.

For each patient, the following data were collected: sociodemographic data (age, sex, geographical origin, marital status, risk factor(s) for HIV acquisition); HIV infection data (CD4 count, AIDS-defining illness, mode of infection); visits to Lausanne University Hospital during the 5 years preceding HIV diagnosis (chronic disease with regular follow-up, inpatient and outpatient consultations) and HIV testing data (date of previous negative HIV test as referred to in clinic letters or obtained from the laboratory database, reason for performing diagnostic test, site of diagnostic test). The limit of 5 years for Lausanne University Hospital visits was selected based on the LP figure of 49.8% of patients newly enrolled in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study,4 in whom infection was likely to have occurred within 5 years preceding diagnosis,25 and the observation that, elsewhere in Europe, 59% of new patients with HIV exhibited HIV ICs during a similar prediagnosis period.26 MOs were identified using medical records and analysed by absolute MO number and by MO category (based on the five groups of HIV testing indications: acute HIV, AIDS-defining illness, HIV ICs, test of exclusion and epidemiological risk).

Given the low HIV testing rates observed in the ED at our centre and elsewhere in French-speaking Switzerland (1% of all patients seen),17 18 we additionally conducted a search of all prediagnosis visits to the ED, using the central hospital database. We focused on ED visits estimated to have occurred after HIV seroconversion based on CD4 cell count at diagnosis, accounting for variations related to age and sex.25 All prediagnosis visits were matched with laboratory reports to determine whether HIV testing had been performed. A single prediagnosis ED visit after which testing was performed within 72 hours was not considered a MO, to allow for patients admitted prior to the weekend or referred for testing by a designated hospital team, where testing may be delayed in the interest of continuity of care. At the time of this study, rapid HIV testing was not available in the ED and so all HIV tests requested and performed were documented in the laboratory database.

Data and statistical analysis

Patient details, stripped of all identifiers, were entered into a coded database by the study investigators (LL, EM) for each of the six 12-month periods. Categorical data were presented as absolute frequencies and percentages and compared using the χ2 test; continuous data were presented as means (SD) or medians (IQR) and analysed using the Mann-Whitney U test. Multivariate logistic regression was applied to calculate the adjusted OR for various risk factors for presenting MOs. Data were stratified according to patient demographic, clinical and epidemiological characteristics in order to reduce confounding. Patients with acute HIV infections were excluded from all analyses concerning LP.

All analyses were performed using Stata V.14.1 (StataCorp).

Results

Patient characteristics

We identified 201 patients newly presenting for HIV care during the study period, all of whom had complete electronic medical records. Mean age at diagnosis was 38 years±SD (range 18–75 years). Mode of HIV transmission was listed as heterosexual in 57% of patients, MSM in 34%, PWID in 4% and unknown in 5% (table 1). The majority of patients (59%) had never been HIV tested prior to their diagnostic test.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of adult patients newly presenting to HIV care in Lausanne, Switzerland between 2010 and 2015 who had not presented any missed opportunity and who had presented at least one missed opportunity

| Demographic characteristic | All patients (n=201) |

Patients with no MO (n=107) |

Patients with ≥1 MO (n=94) |

Univariate analysis (OR±95% CI) |

Multivariate analysis (adjusted OR±95% CI; p values) |

| Age (years), n (%) | |||||

| 18–29 | 56 | 23 (41%) | 33 (59%) | Reference value | |

| 30–49 | 112 | 59 (53%) | 53 (47%) | 0.6 (0.3 to 1.2) | 0.5 (0.3 to 1.1; 0.08) |

| >50 | 33 | 25 (76%) | 8 (24%) | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.6) | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.6; <0.01) |

| Sex, n (%)† | |||||

| Male | 126 | 66 (52%) | 60 (48%) | Reference value | |

| Female | 75 | 41 (55%) | 34 (45%) | 1.09 (0.6 to 1.9) | 0.7 (0.3 to 1.5; 0.36) |

| Geographical origin, n (%) | |||||

| Europe, North America, Australasia | 106 | 58 (55%) | 48 (45%) | Reference value | |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 66 | 32 (49%) | 34 (51%) | 1.2 (0.7 to 2.4) | 3.5 (1.3 to 7.7; 0.01) |

| Other‡ | 29 | 17 (59%) | 12 (41%) | 0.9 (0.4 to 2.0) | 1.0 (0.4 to 2.5; 0.96) |

| Chronic Illness, n (%) | |||||

| No | 161) | 92 (57%) | 69 (43%) | Reference value | |

| Yes | 40 | 15 (37%) | 25 (63%) | 2.2 (1.1 to 4.5) | 4.4 (1.7 to 10.9, <0.01) |

| Mode of transmission, n (%) | |||||

| Heterosexual | 114 | 67 (59%) | 47 (41%) | Reference value | |

| MSM | 68 | 29 (43%) | 39 (57%) | 1.91 (1.0 to 3.5)* | 4 (1.5 to 10.7; 0.01) |

| PWID | 9 | 3 (33%) | 6 (67%) | 2.8 (0.7 to 12) | 2.9 (0.6 to 15.3; 0.20) |

| Unknown | 10 | 8 (80%) | 2 (20%) | 0.3 (0.7 to 1.8) | 0.3 (0.1 to 1.8; 0.2) |

| Time since previous HIV test, n (%) | |||||

| No previous test | 119 | 72 (61%) | 47 (39%) | Reference value | |

| ≤1 year | 28 | 12 (43%) | 16 (57%) | 2.0 (0.9 to 4.7) | 1.6 (0.6 to 4.3; 0.38) |

| >1 year ago | 54 | 23 (43%) | 31 (57%) | 2.0 (1.0 to 4.0)* | 1.4 (0.7 to 3.0; 0.31) |

*P<0.05.

†There were no transgender patients in the group studied.

‡Asia, South America, North Africa, Middle East.

MO, missed opportunity; MSM, men who have sex with men; PWID, people who inject drugs.

Missed opportunities

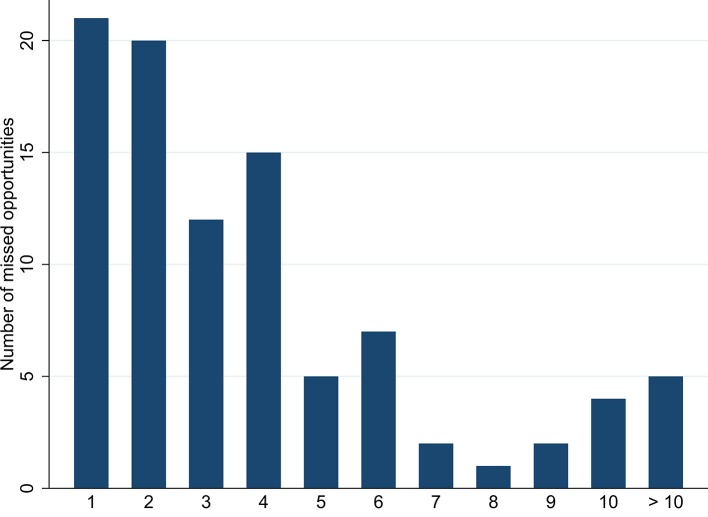

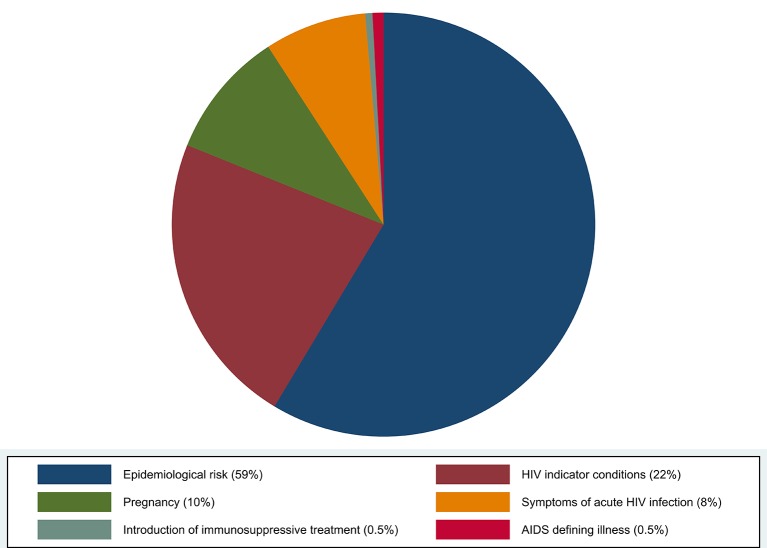

In total, 359 separate MOs were presented by 94 patients (47%) during the 5 years preceding their diagnosis (figure 1). Considering patients presenting MOs, 74 patients (78%) had presented on more than one visit (range 2–17) with a MO of any category. Considering MO categories, 58 patients (62%) had presented a single category of MO, 30 patients had presented two categories (32%) and 6 patients (6%) had presented three categories. Figure 2 shows the distribution of MO categories by testing indication.

Figure 1.

Histogram showing the percentage of MOs occurring during the 5 years preceding diagnosis in adult patients newly presenting for HIV care between 2010 and 2015 in Lausanne, Switzerland. MOs, missed opportunities.

Figure 2.

Pie chart showing the distribution of the categories of missed opportunities experienced between 2010 in adult patients newly presenting for HIV care in Lausanne, Switzerland.

Risk factors for MOs

In multivariate analysis, older patients (aged >50 years) had less risk of presenting MOs than patients aged <30 years (p=0.01), while patients of sub-Saharan African origin (p=0.01), those under regular follow-up for chronic illness (p=0.01) and MSM (p=0.02) had increased risk (table 1). In patients from sub-Saharan Africa and those under regular follow-up for chronic illness, all MO categories were distributed equally compared with the rest of the population. In contrast, MOs in MSM patients were more frequently related to epidemiological risk (46%) than to other MO categories (33%) (p<0.01).

Clinical presentation at diagnosis, site of testing and reason for testing

Most patients (85%) were diagnosed in the chronic phase of infection (table 2). The median CD4 count at diagnosis was 293 (IQR 147–452). In total, 119 (59%) were LPs. LPs consulted less often to Lausanne University Hospital than non-LPs (mean number of consults 1.4 for LPs vs 2.5 for non-LPs, p<0.01).

Table 2.

Clinical presentation, site of testing and reason for testing at time of diagnostic HIV test among all patients presenting to care for a newly diagnosed HIV infection between 2010 and 2015 in Lausanne, Switzerland

| No of patients, n (%) | |

| Clinical presentation | |

| Acute HIV infection | 30 (15) |

| Chronic HIV infection: | |

| CD4 count >350 cells/mm3 | 65 (32) |

| Late presenters (<350 cells/mm3) | 44 (22) |

| Advanced disease (<200 cells/mm3) | 62 (31) |

| Site of diagnostic HIV test | |

| Primary care | |

| Primary care physician | 64 (32) |

| Anonymous consultation | 26 (13) |

| Lausanne University Hospital | |

| Outpatient care | 41 (20) |

| Inpatient care | 17 (8) |

| Emergency department | 4 (2) |

| Gynaecology/obstetrics | 16 (8) |

| Infectious diseases service | 5 (3) |

| Other | 28 (14) |

| Reason for testing | |

| HIV indicator condition | 59 (29) |

| Epidemiological risk | 42 (21) |

| Symptoms/signs of acute HIV infection | 36 (18) |

| AIDS-defining illness | 21 (10) |

| Pregnancy | 14 (7) |

| Prior to immunosuppressive treatment | 1 (1) |

| Patient initiated | 28 (14) |

A greater proportion of new HIV diagnoses were made in the primary care and outpatient settings than during hospital admission (table 2). The top three reasons for testing, regardless of testing site, were presence of HIV ICs, epidemiological risk and symptoms and signs of acute HIV infection (online supplementary table S2). Acute HIV infection was confirmed in 24 of the 36 patients presenting with symptoms and signs of acute HIV infection (online supplementary table S3).

We did not identify any situations in which HIV testing was proposed but declined by the patient.

MOs and LP

Multivariate analysis demonstrated a lower risk of LP in patients presenting MOs (OR 0.5, 95% CI 0.2 to 0.9, p<0.01). Indeed, the median CD4 count at diagnosis among MO patients was significantly higher than for non-MO patients (351 cells/mm3 vs 244 cells/mm3, p<0.01). MOs were less frequent in LPs compared with patients presenting with CD4 >350 cells/mm3 (42.5% vs 57.5%, p<0.01). Among subgroups, the LP rate among MSM was lower compared with the rest of the study population (22% vs 78%, p<0.001).

MOs in the ED

Of 201 patients, 58 (29%) were identified as having presented to the ED prior to diagnosis, 27 of whom (47%) had presented more than once (range 2–7 visits). All 58 patients had presented within 3 years preceding their HIV diagnosis and 53 patients (91%) within the preceding 12 months. Although 15 patients (26%) were diagnosed within 72 hours of their most recent ED visit, 7 of these had presented to the ED on at least one previous occasion. In total, 50/58 patients (86%) presented to the ED during the interval between seroconversion and diagnosis, none of whom were tested. As with the patient sample as a whole, the two main MO categories for these 58 patients were epidemiological risk and HIV ICs.

Discussion

In this single-centre study, we observed that 47% of 201 patients newly presenting for HIV care had presented at least one MO for earlier testing. Although 30 patients (15%) were diagnosed during acute infection, 9 patients (5%) who presented with symptoms or signs of acute HIV were not tested. Of patients who had visited the ED prediagnosis, 86% had presented at least one MO for testing. Finally, MOs occurred significantly less frequently in LPs than in non-LPs.

Our patient population differed from that of Switzerland as a whole (Swiss Federal Office of Public Health HIV notifications) in terms of HIV acquisition risk profile: 57% heterosexual transmission and 34% MSM, compared with 42% heterosexual and 57% MSM.27 As heterosexual transmission was a risk factor for LP in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study by Hachfeld et al, this might explain our higher rate of LPs (59%) compared with the Swiss HIV Cohort Study figure of 49.8%.4 A lower Swiss HIV Cohort Study figure through under-representation of our patients in the Hachfeld et al study is unlikely as the majority were enrolled in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study.

Our analysis showed that patients under regular follow-up for chronic illness, patients from sub-Saharan Africa and MSM were at increased risk for MOs. In patients under regular follow-up, there may be the assumption by the hospital physician that the patient’s primary care physician has performed an HIV test and vice versa.1 In our institution, we have previously reported suboptimal testing rates among oncology patients, particularly those of non-European origin.28 Among patients with risk factors for HIV acquisition, MOs will occur if there is non-disclosure of at-risk behaviour by the patient and incomplete history taking by the doctor. This was described in a French cross-sectional study of 1008 patients newly diagnosed with HIV of whom 48% were MSM.29 Fewer than half the MSM who consulted disclosed being MSM and only 21% of all MSM were offered testing by their healthcare provider.29 In Switzerland, physicians frequently do not discuss sexual behaviour with their patients, potentially missing such risk factors.30 31

Our non-association between LPs and MOs suggests a distinction between ‘missed’ opportunity and ‘no’ opportunity. While it is logical that LP may result from repeated MOs in positive individuals, LPs do not necessarily present opportunities for earlier testing. If individuals feel well, are unaware of HIV risk factors and/or have poor access to healthcare, they may have sporadic if any contact with healthcare systems4: their LP may be their only presentation. However, this interpretation is limited by the fact that we were unable to quantify MOs potentially occurring in primary care.

We have observed in our study that LPs consult less frequently to our hospital. Optimal HIV testing practice is the cornerstone towards attaining the first 90 of the 90-90-90 goal set by WHO.32 However, even perfect PICT practice cannot eliminate LP when physicians can initiate testing only if individuals present to them. It is necessary to reach out to individuals who are at risk of infection but who do not present for healthcare. HIV testing can be expanded by introducing community-level testing innovations tailored to each community, depending on whether non-presentation is related to lack of awareness of HIV risk factors or symptoms of infection or to lack of awareness of services available. An obstacle to HIV testing in Switzerland is that HIV testing may require expenditure by the patient, even if this is later reimbursed by health insurance. Innovations to improve access to testing include walk-in centres with free testing, testing by non-traditional providers, improving risk perception and tackling stigma.33

Regarding risk perception, the MO umbrella can be extended from MOs for HIV testing to those for HIV prevention. Whether or not the patients in this sample had HIV at their first few visits to Lausanne University Hospital, they were, by definition, at risk of HIV acquisition. Delivering a prevention message at the time of testing could avert future infection and may also be a means of reaching individuals outside the hospital by dissemination of information. In the ED at our centre, offering non-targeted screening, as recommended in the USA34 and the UK,35 would have enabled diagnosis of 86% of the patients of our sample who had presented to this service. While data from our ED are lacking regarding the cost-effectiveness of non-targeted screening per new HIV diagnosis made, the prevention message that comes with screening could reduce onward transmission among contacts in the community.

The MO rates at our centre were higher than those reported in other studies of similarly sized samples of newly diagnosed patients presenting for HIV care in European hospital outpatient settings. Tominski et al observed a rate of 21% among 270 patients, based on HIV ICs12; Noble et al observed a rate of 16.3% among 124 patients, based on ICs or AIDS-defining illness up to 5 years prediagnosis14; Gullón et al observed a rate of 14.5% among 354 patients, based on ICs up to 1-year prediagnosis.15 As there is no consensus definition of MOs, it is important to examine the criteria for MOs and the time prior to diagnosis examined. In our study, the MO definition was wide, based on HIV ICs and AIDS-defining illness and on epidemiological risk, symptoms and signs of acute HIV infection and situations in which HIV should be excluded, and over a period of 5 years prediagnosis. Considering MOs based on HIV ICs and AIDS-defining illness alone, our MO rate was 16%. However, applying the most recent HIV testing recommendations, we consider the MO rate obtained according to our study criteria as being a baseline on which to improve. Considering future directions, we plan to apply the findings from this study in several ways. We have piloted rapid testing in the ED by screening patients for HIV risk factors using anonymous electronic tablet-based questionnaires in the waiting area to improve HIV testing in this service36. The lack of testing among pregnant women who are consulting to terminate their pregnancy is illogical and merits review of obstetrical guidelines. Finally, ICs should be mentioned in the practice guidelines of relevant (non-HIV) specialties.23

This study has limitations. As in any retrospective study, identifying and classifying MOs relied on available clinical documentation. As we reviewed medical notes only from our institution, the number or categories of MO may be prone to bias. The date of the last performed HIV test may also be prone to recall bias. However, while the number of included patients was small, complete medical records for each patient ensured data quality. This study examined only MOs occurring in our hospital; using the Lausanne University Hospital database it was not possible to quantify potential MOs occurring in the primary care setting or in other hospitals. We could therefore have underestimated the number of MOs. On the other hand, although we could determine that most diagnostic tests were made in the primary care setting, this study did not examine the untested patient denominator. As we have no means of quantifying HIV testing performed in the primary care setting, we cannot exclude an overestimation of the number of MOs for our population. Finally, as our study was monocentric, our risk-factor associations with MOs reflect our local patient population. Against these limitations, the non-association between LP and MOs observed in our study has important implications for a national testing strategy based on PICT, as many individuals who need to be tested do not access healthcare before the event that leads to HIV diagnosis.

In conclusion, by defining MOs according to the most recent national HIV testing recommendations, we observe that 47% of the patients newly presenting for HIV care at our centre could have been tested at an earlier stage. The lower rate of LPs among patients presenting MOs suggests that the PICT approach must now be expanded to reach at-risk communities rather than waiting for these individuals to become sufficiently symptomatic to access care themselves.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are most grateful to the patients at our infectious diseases outpatient clinic who made it possible for us to perform this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: LL contributed to study design, data collection, data analysis, manuscript preparation and critical review. EM contributed to study design, data collection and manuscript preparation. OH contributed to manuscript preparation and critical review. MC contributed to study design and critical review. KEAD contributed to study design, data analysis, manuscript preparation and critical review.

Funding: This work was funded by the Infectious Diseases Service of the Lausanne University Hospital.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Ethical Committee on Human Research of the Canton of Vaud, Switzerland (protocol number 2016–00333).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Extra data can be accessed via the Dryad data repository at http://datadryad.org/ with the doi:10.5061/dryad.8jf67k4.

References

- 1. Darling KE, Hachfeld A, Cavassini M, et al. Late presentation to HIV care despite good access to health services: current epidemiological trends and how to do better. Swiss Med Wkly 2016;146:w14348 10.4414/smw.2016.14348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mocroft A, Lundgren JD, Sabin ML, et al. Risk factors and outcomes for late presentation for HIV-positive persons in Europe: results from the Collaboration of Observational HIV Epidemiological Research Europe Study (COHERE). PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001510 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kohler P, Schmidt AJ, Cavassini M, et al. The HIV care cascade in Switzerland: reaching the UNAIDS/WHO targets for patients diagnosed with HIV. AIDS 2015;29:2509–15. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hachfeld A, Ledergerber B, Darling K, et al. Reasons for late presentation to HIV care in Switzerland. J Int AIDS Soc 2015;18:20317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Office fédéral de la santé publique. Dépistage du VIH et conseil initiés par les médecins. Bulletin de l’OFSP 2007;21:371–3. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Office fédéral de la santé publique. Dépistage du VIH effectué sur l’initiative des médecins: recommandations pour les patients adultes. Bulletin de l’OFSP 2010:364–6. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Office fédéral de la santé publique. Dépistage du VIH effectué sur l’initiative des médecins en présence de certaines pathologies (maladies évocatrices d’une infection à VIH). Bulletin de l’OFSP 2013:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Office fédéral de la santé publique. Dépistage du VIH effectué sur l’initiative des médecins. Bulletin de l’OFSP 2015;21:237–41. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Biller-Andorno N, Zeltner T. Individual Responsibility and Community Solidarity--The Swiss Health Care System. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2193–7. 10.1056/NEJMp1508256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Darling KE, Gloor E, Ansermet-Pagot A, et al. Suboptimal access to primary healthcare among street-based sex workers in southwest Switzerland. Postgrad Med J 2013;89:371–5. 10.1136/postgradmedj-2012-131001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. De Rossi N, Dattner N, Cavassini M, et al. Patient and doctor perspectives on HIV screening in the emergency department: A prospective cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2017;12:e0180389 10.1371/journal.pone.0180389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tominski D, Katchanov J, Driesch D, et al. The late-presenting HIV-infected patient 30 years after the introduction of HIV testing: spectrum of opportunistic diseases and missed opportunities for early diagnosis. HIV Med 2017;18 10.1111/hiv.12403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Joore IK, Reukers DF, Donker GA, et al. Missed opportunities to offer HIV tests to high-risk groups during general practitioners’ STI-related consultations: an observational study. BMJ Open 2016;6:e009194 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Noble G, Okpo E, Tonna I, et al. Factors associated with late HIV diagnosis in North-East Scotland: a six-year retrospective study. Public Health 2016;139:36–43. 10.1016/j.puhe.2016.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gullón A, Verdejo J, de Miguel R, et al. Factors associated with late diagnosis of HIV infection and missed opportunities for earlier testing. AIDS Care 2016;28:1296–300. 10.1080/09540121.2016.1178700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Levy I, Maor Y, Mahroum N, et al. Missed opportunities for earlier diagnosis of HIV in patients who presented with advanced HIV disease: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2016;6:e012721 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Darling KE, de Allegri N, Fishman D, et al. Awareness of HIV testing guidelines is low among Swiss emergency doctors: a survey of five teaching hospitals in French-speaking Switzerland. PLoS One 2013;8:e72812 10.1371/journal.pone.0072812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Darling KE, Hugli O, Mamin R, et al. HIV testing practices by clinical service before and after revised testing guidelines in a Swiss University Hospital. PLoS One 2012;7:e39299 10.1371/journal.pone.0039299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. UNAIDS. UNAIDS epidemiology figures 2013: Switzerland. http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/epidocuments/CHE.pdf2013

- 20. Schoeni-Affolter F, Ledergerber B, Rickenbach M, et al. Cohort profile: the Swiss HIV Cohort study. Int J Epidemiol 2010;39:1179–89. 10.1093/ije/dyp321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Antinori A, Coenen T, Costagiola D, et al. Late presentation of HIV infection: a consensus definition. HIV Med 2011;12:61–4. 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2010.00857.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fiebig EW, Wright DJ, Rawal BD, et al. Dynamics of HIV viremia and antibody seroconversion in plasma donors: implications for diagnosis and staging of primary HIV infection. AIDS 2003;17:1871–9. 10.1097/01.aids.0000076308.76477.b8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lord E, Stockdale AJ, Malek R, et al. Evaluation of HIV testing recommendations in specialty guidelines for the management of HIV indicator conditions. HIV Med 2017;18:300–4. 10.1111/hiv.12430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sullivan AK, Raben D, Reekie J, et al. Feasibility and effectiveness of indicator condition-guided testing for HIV: results from HIDES I (HIV indicator diseases across Europe study). PLoS One 2013;8:e52845 10.1371/journal.pone.0052845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lodi S, Phillips A, Touloumi G, et al. Time from human immunodeficiency virus seroconversion to reaching CD4+ cell count thresholds <200, <350, and <500 Cells/mm³: assessment of need following changes in treatment guidelines. Clin Infect Dis 2011;53:817–25. 10.1093/cid/cir494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Joore IK, Arts DL, Kruijer MJ, et al. HIV indicator condition-guided testing to reduce the number of undiagnosed patients and prevent late presentation in a high-prevalence area: a case-control study in primary care. Sex Transm Infect 2015;91:467–72. 10.1136/sextrans-2015-052073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Office fédéral de la santé publique. Statistiques, analyses et tendances VIH/IST. http://www.bag.admin.ch/hiv_aids/05464/12908/12909/12913/index.html?lang=fr2014

- 28. Merz L, Zimmermann S, Peters S, et al. Investigating barriers in HIV-testing oncology patients: The IBITOP Study, Phase I. Oncologist 2016;21:1176–82. 10.1634/theoncologist.2016-0107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Champenois K, Cousien A, Cuzin L, et al. Missed opportunities for HIV testing in newly-HIV-diagnosed patients, a cross sectional study. BMC Infect Dis 2013;13:200 10.1186/1471-2334-13-200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dubois-Arber F, Meystre-Agustoni G, André J, et al. Sexual behaviour of men that consulted in medical outpatient clinics in Western Switzerland from 2005-2006: risk levels unknown to doctors? BMC Public Health 2010;10:528 10.1186/1471-2458-10-528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Meystre-Agustoni G, Jeannin A, de Heller K, et al. Talking about sexuality with the physician: are patients receiving what they wish? Swiss Med Wkly 2011;141:w13178 10.4414/smw.2011.13178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fauci AS, Marston HD. Ending the HIV-AIDS pandemic--follow the science. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2197–9. 10.1056/NEJMp1502020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bath R, O’Connell R, Lascar M, et al. TestMeEast: a campaign to increase HIV testing in hospitals and to reduce late diagnosis. AIDS Care 2016;28:1–4. 10.1080/09540121.2015.1120855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep 2006;55:1–17. quiz CE1-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. British HIV Association, British Association of Sexual Health and HIV, British Infection Society. UK national guidelines for HIV Testing 2008. 2008. http://www.bhiva.org/documents/Guidelines/Testing/GlinesHIVTest08.pdf

- 36. Gillet C, Darling KEA, Senn N, et al. Targeted versus non-targeted HIV testing offered via electronic questionnaire in a Swiss emergency department: A randomized controlled study. PLoS One 2018;13:e0190767 10.1371/journal.pone.0190767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-019806supp001.pdf (56.1KB, pdf)