Abstract

Objective

Establishing a peripheral intravenous catheter (PIVC) after a long intensive care unit (ICU) stay can be a challenge for nurses, as these patients may present vascular access issues. The aim of this study was to compare an ultrasound-guided method (UGM) versus the landmark method (LM) for the placement of a PIVC in ICU patients who no longer require a central intravenous catheter (CIVC).

Design

Randomised, controlled, prospective, open-label, single-centre study.

Setting

Tertiary teaching hospital.

Participants

114 awake patients hospitalised in ICU fulfilling the following criteria: (1) with a central venous catheter that was no longer required, (2) needing a PIVC to replace the central venous catheter and (3) with no apparent or palpable veins on upper limbs after tourniquet placement.

Intervention

Placement of a PIVC using an UGM.

Primary outcome

Number of attempts for the establishment of a PIVC in the upper limbs.

Results

57 patients were respectively included in both the UGM group and LM group. Stasis oedema in the upper limbs was the main cause of poor venous access identified in 80% of patients. Both the number of attempts (2 (1–4), p=0.911) and catheter lifespan ((3 (1–3) days and 3 (2–3) days, p=0.719) were similar between the two groups. Catheters in the UGM group tended to be larger (p=0.059) and be associated with increased extravasation (p=0.094).

Conclusion

In ICU patients who no longer require a CIVC, use of an UGM for the establishment of a PIVC is not associated with a reduction in the number of attempts compared with LM.

Trial registration number

Keywords: ultrasonography, vascular access device

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Randomised, controlled and intention-to-treat study.

Selection bias prevented by excluding any prior attempt with the landmark method (LM) before inclusion.

Sample size may have been insufficient, that is, a greater number of attempts with the LM was expected compared with the number of attempts observed.

Potential insufficient nurse training resulting in differing skill levels for operators.

Introduction

The peripheral intravenous catheter (PIVC) is one of the most common and early medical devices placed in patients at hospital admission, particularly in emergency situations.1 In this latter setting, establishment of a PIVC may be crucial for the management of patients who are critically ill in a timely manner. The landmark method (LM) is the most widely used technique but is also associated with a high risk of failure due to the conjunction of the emergency setting and of a frequently poor peripheral venous network.2 A substantial body of literature supports the use of the ultrasound-guided method (UGM) as a second option in patients with a poor peripheral venous network in order to obtain a stable and safe peripheral venous access. However, contrary to the USA where catheters are most often placed by emergency physicians and technicians and not nurses, the situation is reversed in France (in keeping with European standards), where critical care nurses are the ones responsible for the placement of PIVCs.3–7 Only one randomised study conducted in selected trained emergency nurses has demonstrated that, in anticipated difficult intravenous access patients, an UGM was associated with a higher success rate compared with the LM.8 Vascular access in intensive care unit (ICU) is, on the other hand, a specific condition which cannot be compared with the emergency department setting.

At admission in the ICU, PIVC is not a major goal, since patients most often require a central intravenous catheter (CIVC). By opposition, at the other extreme of medical management, patient discharge to the ICU wards is marked by the removal of the CIVC inserted at admission. Early removal should reduce the duration of CIVC maintenance. However, the establishment of a PIVC may represent a challenge for the nurse in charge. Accordingly, in the only published study, Kerforne et al demonstrated that almost 80% of the 60 patients requiring a PIVC in ICU presented stasis oedema in the upper limbs. The authors also demonstrated the efficiency of UGM (70% success rate) compared with LM (37% success rate). However, reasons for placement of the PIVC and the caregivers responsible for performing the UGM were not specified, with the crossover design precluding any firm conclusion.9

In light of the above, we designed a randomised study conducted by critical care nurses in order to assess the effectiveness of the UGM compared with the LM for the placement of a PIVC in upper limbs in patients with anticipated difficult PIVC access and who no longer required a CIVC.

Methods and setting

This prospective randomised, non-blinded, single-centre controlled trial was conducted in the medical ICU of a tertiary care teaching hospital (Nancy, Vandoeuvre-les-Nancy, France).

Ethical approval

Since landmark and ultrasound-guided methods were both part of standard care in our unit, the ethics committee waived patient consent (Ethics Committee of the Nancy University Hospital CPP EST III, number 14.09.01). However, the French data protection authority (CNIL: Commission National de l’Informatique et des Libertés), independently of the Ethics committee, requested that non-opposition be collected for the purposes of acquiring numerical data. The trial was registered on the clinicaltrial.gov website under the identification number NCT02285712.

Patient population

Included in this trial were patients over 18 years of age who fulfilled the following criteria: (1) awake patients hospitalised in ICU, (2) with a CIVC that was no longer required, (3) need of PIVC to replace the CIVC and (4) no apparent or palpable veins in upper limbs after tourniquet placement due to body mass index>30, fluid overload, previous history of intravenous drug abuse or chemotherapy. Exclusion criteria were patients under 18 years of age, pregnancy, patient under protective supervision and need for a CIVC.

The CIVC was no longer required if the patient was not under deep sedation, was haemodynamically stable (no catecholamine support) and with a remaining duration of intravenous antibiotics inferior to 5 days. In ICU, CIVC necessity is a common routine, assessed daily by the nurse in charge of the patient with a checklist to fulfil.

Patients were considered to have a poor bilateral upper limb venous network if no vein was apparent or palpable after tourniquet placement due to one of the following causes: fluid overload with stasis oedema, overweight with a body mass index >30 kg/m2, therapy-related venous toxicity or past history of intravenous drug abuse.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and public were not involved in the design or conduct of this study.

Nurse training

All nurses participated in the study. Seventy per cent of the nurses were trained for the UGM and 100% of nurses were proficient in LM before starting the study. A two-phase educational programme on UGM for PIVC catheterisation was conducted in our unit between January and December 2014 for all nurses. The first phase consisted in a theoretical 1 hour lecture, which was given by a physician. It consisted in three parts: the ultrasonic principles, the anatomy of the veins of the upper limb and the UGM. At the end of the theoretical teaching, nurses were required to obtain four supervised successful PIVC placements with the UGM in living patients before being certified. A physician and three certified nurses carried out the supervision of practical training for the entire paramedical team. A preliminary study confirmed that there was no improvement in the success rate between the third and fourth attempt during the practical training phase (online supplementary data material 1, figure S1).

bmjopen-2017-020220supp003.pdf (70.1KB, pdf)

Conduct of the study

Patients could be included 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. When a patient was eligible, the nurse in charge along with the physician provided an information sheet to the patient. While no written consent was required, non-opposition was systematically obtained and recorded in the medical file prior to inclusion. Thereafter, the nurse opened a sealed envelope containing the randomised insertion technique. After randomisation, the nurse was allowed three attempts per day during 3 days. Each ‘attempt’ day represented three punctures with three different catheters. Only one puncture was allowed with the same catheter. The length of the catheter was 1.16 inches in all instances whereas the diameter (in gauge) was left to the nurse’s discretion.

A successful placement was defined by easy fluid infusion and absence of local infiltration. After successful placement of the PIVC, the CIVC was removed and sent for bacteriological assessment. The PIVC was immediately and constantly used after its placement. Antecubital veins at the elbow level were not allowed to be punctured due to the high risk of early dislodgment of the catheter during flexion/extension movements of the arm. Assessors were not blinded to the allocation arm.

Outcome measurement

The main outcome was the number of attempts to obtain a stable PIVC. An attempt was defined as one percutaneous needle puncture. A successful attempt was defined by infusion through the catheter without local tissue infiltration. A successful placement at the first attempt was defined as the best-case scenario. Secondary outcomes included: the proportion of successful PIVC placements for each day (success rate), diameter of the inserted catheter, duration of the catheter defined as the period between insertion and removal with a maximum of 3 days, number of CIVCs removed, number of CIVC-related colonisations, duration of the CIVC defined as the period between insertion and removal immediately after PIVC catheterisation, patient satisfaction recorded on each attempt day until successful catheterisation (from 0: no satisfaction to 10: totally satisfied; survey provided in online supplementary data material 2).

bmjopen-2017-020220supp004.pdf (48.9KB, pdf)

Data collection

In addition to demographic data, the following were collected: reason for admission, simplified acute physiology II (SAPS II) score, duration of catecholamine support, mechanical ventilation and renal replacement therapy. Localisation (femoral, jugular, subclavian) and duration of CIVC maintenance were recorded. Causes of poor venous network as defined in the study population were recorded. The number of colonisations and bacteria involved (defined as a positive culture of the central catheter tip >1000 colony-forming units per plate) were reported.

Sample size calculation

Based on the literature and on the results of the training phase, it was estimated that the median number of attempts with the UGM would be three, whereas the median number of attempts with the LM would be five. A sample of 96 patients was needed to identify a difference of two attempts (SD=3) with a β risk at 0.1 and a two-tailed α at 0.05. Considering that a normal distribution would be unlikely, an inflation rate of 15% was included and therefore an enrolment of 114 patients was planned.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean±SD, median with IQR or proportions as appropriate. Normality of the distribution was assessed by visual inspection. A Student’s t test and Mann-Whitney test were used to compare continuous variables, while the χ² test or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare proportions. All statistical analyses were performed using Rstudio (RStudio V.1.1.136, Boston, USA) with a p<0.05 considered to be statistically significant.

Results

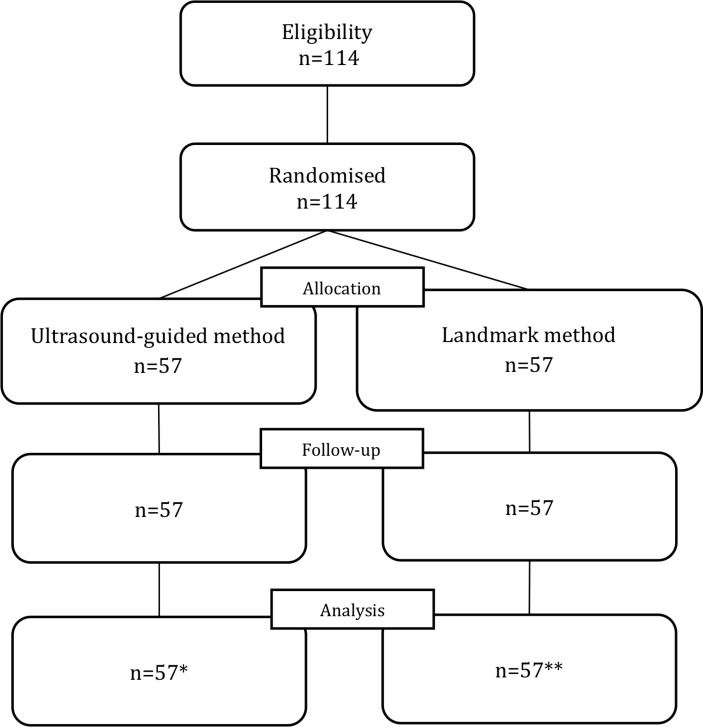

One hundred fourteen patients were included in this study with 57 patients randomised in each group between March 2015 and January 2017 (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart. *One case lost in the ultrasound-guided method group. **One patient did not receive the intervention because of clinical deterioration.

Population characteristics

Table 1 describes the clinical characteristics of the population included in the study. Briefly, there were no differences with regard to age, female gender and SAPS II score at admission. Acute respiratory failure was the primary cause of admission (57% in the UGM group versus 43% in the LM group, p=0.186) followed by cardiogenic shock (29% in both groups) and septic shock (21% in the UGM group versus 25% in the landmark group, p=0.823). Patients underwent mechanical ventilation in 84% of cases in the UGM group versus 95% in the LM group (p=0.124). Moreover, catecholamines were required in 75% of cases in both groups. Last, 20% of patients underwent renal replacement therapy in the UGM group versus 32% in the LM group (p=0.196).

Table 1.

Description of the study population according to the insertion technique

| Variables | Ultrasound-guided method, n=57 | Landmark method, n=57 |

| n, %, m±SD, median (IQR)* | n, %, m±SD, median (IQR)† | |

| Demographic variables | ||

| Age | 65.5 (52–75.8) | 64.0 (49-72) |

| Female gender | 22/56 (39%) | 22/56 (39%) |

| Admission causes | ||

| Cardiogenic shock | 16/56 (29%) | 16/56 (29%) |

| Septic shock | 12/56 (21%) | 14/56 (25%) |

| Haemorrhagic shock | 1/56 (02%) | 1/56 (02%) |

| Acute respiratory failure | 32/56 (57%) | 24/56 (43%) |

| Criteria for difficult peripheral venous access | ||

| Fluid overload with stasis oedema | 45/56 (80%) | 47/57 (82%) |

| Obesity | 21/56 (38%) | 17/57 (30%) |

| Prior drug abuse or venotoxic medications | 13/56 (23%) | 17/57 (30%) |

| Severity | ||

| SAPS II | 51±17 | 54±22 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 47/56 (84%) | 53/56 (95%) |

| Duration of mechanical ventilation in days‡ | 8 (4 -15) | 7.5 (4-20) |

| Catecholamines | 42/56 (75%) | 42/56 (75%) |

| Duration of catecholamines in days‡ | 2 (1–5.75) | 4 (2–5) |

| Renal replacement therapy | 11/56 (20%) | 18/56 (32%) |

| Duration of renal replacement therapy in days†§ | 2 (2–5) | 11 (6–15) |

Comparisons between the groups were performed using the Student or Mann Whitney test for quantitative variables and the χ² test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables.

*One case lost.

†One patient presented an unexpected clinical deterioration before the first attempt.

‡In-patients who had the treatment.

§P=0.008.

SAPS II, simplified acute physiology II.

Difficult PIVC criteria

Fluid overload with stasis oedema of the upper limbs was observed in 80% for the UGM group and 82% in the LM group (p=0.964); 38% and 30% of the patients were overweight with a body mass index >30 kg/m2 in the UGM and LM groups, respectively (p=0.507) (table 1).

Principal outcome results according to insertion method

The crude median number of attempts did not differ between the UGM and the LM groups (2 (1–4) in both groups, p=0.911). A sensitivity analysis paragraph is provided at the end of this section describing the procedure used for imputation of the two patients with no data for the principal outcome.

On the first day, the success rate was 66% in the UGM group versus 70% in the LM group (p=0.84) (table 2). At first attempt, 41% of catheterisations were successful in the UGM group versus 33% in the LM group (p=0.886). Finally, from the second day onward, only 18 patients remained in the UGM group and 17 in the LM group with no difference in success rate between the two groups for days 2, 3 and 4. The global success rate was 98% in the UGM group and 95% in the LM group (p=0.618). There was no difference in number of attempts throughout the inclusion period (divided in three equal time periods) with the two methods (online supplementary data material 3, table S1).

Table 2.

Successful cannulation rate according to insertion technique

| Variables | Ultrasound-guided method, n=57* | Landmark method, n=57* | P value | P value |

| n, %, median (IQR) | n, %, median (IQR) | |||

| Day 1 | ||||

| Success at the first attempt | 23/56 (41%) | 18/55 (33%) | 0.886 | |

| Success at the second attempt | 8/56 (14%) | 13/55 (24%) | ||

| Success at the third attempt | 6/56 (11%) | 7/55 (13%) | ||

| Failure at the third attempt | 19/56 (34%) | 17/55 (31%) | ||

| % success | 37/56 (66%) | 39/56† (70%) | 0.840 | |

| Day 2 | ||||

| Success at the first attempt | 5/16 (31%) | 6/17 (35%) | 1.000 | |

| Success at the second attempt | 2/16 (13%) | 3/17 (18%) | ||

| Success at the third attempt | 1/16 (06%) | 1/17 (06%) | ||

| Failure at the third attempt | 8/16 (50%) | 7/17 (41%) | ||

| % success | 8/16‡ (50%) | 10/17 (59%) | 0.874 | |

| Day 3 | ||||

| Success at the first attempt | 3/9 (33%) | 1/6 (17%) | 0.536 | |

| Success at the second attempt | 1/9 (11%) | 0/6 (00%) | ||

| Success at the third attempt | 1/9 (11%) | 1/6 (17%) | ||

| Failure at the third attempt | 4/9 (44%) | 4/6 (67%) | ||

| % success | 5/9§ (56%) | 2/6§ (33%) | 0.608 | |

| Day 4 | ||||

| Success at the first attempt | 1/4 (25%) | 0/4 (00%) | 0.617 | |

| Success at the second attempt | 1/4 (25%) | 1/4 (25%) | ||

| Success at the third attempt | 1/4 (25%) | 0/4 (00%) | ||

| Failure at the third attempt | 1/4 (25%) | 3/4 (75%) | ||

| % success | 3/4 (75%) | 1/4 (25%) | 0.486 | |

| Global success | 53/54 (98%) | 52/55 (95%) | 0.618 |

Comparisons between the groups were performed using the Student or Mann Whitney test for quantitative variables and the χ² test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables.

*One case lost in the UGM group, one patient in the LM group presented an unexpected clinical deterioration before the first attempt

†One patient was successfully cannulated but with no record on the number of attempts.

‡In UGM group, at day 2, two patients were not punctured and one patient deceased between days 1 and 2.

§Two patients deceased between days 2 and 3 in UGM group and in LM group.

bmjopen-2017-020220supp001.pdf (47.2KB, pdf)

Secondary outcome results

PIVC lifespan was similar between the two groups (UGM group: 3 (1–3) versus LM group: 3 (2–3), p=0.719). Larger-diameter catheters tended to be placed in the UGM group (18 G (18–21)) compared with those in the LM group (21 G (18–21), p=0.059). Extravasation tended to be more frequent in the UGM group than in the LM group (34% vs 18%, p=0.094). The proportion of central venous catheter removals was similar between the two groups. No difference was found between groups in terms of duration of CIVC maintenance (table 3).

Table 3.

Secondary outcomes

| Variables | Ultrasound-guided method | Landmark method | P value* |

| n, %, median (IQR), n=57† | n, %, median (IQR), n=57‡ | ||

| Peripheral venous access | |||

| Peripheral venous access lifetime (days) | 3 (1–3) | 3 (2–3) | 0.719 |

| Diameter of the catheter in Gauge | |||

| Day 1 | 18 (18–21) | 18 (18–21) | 0.059 |

| Day 2 | 18 (18–21) | 21 (18–21) | |

| Day 3 | 18 (18–21) | 21 (18–21) | |

| Day 4 | 21 (18–21) | 18 (18–18) | |

| All days | 18 (18–21) | 21 (18–21) | |

| Reasons for removal | |||

| Extravasation | 18/53 (34%) | 9/51 (18%) | 0.094 |

| Accidental catheter removal | 2/53 (4%) | 6/51 (12%) | 0.157 |

| Pain | 0/53 (0%) | 0/51 (0%) | --- |

| Bleeding | 0/53 (0%) | 0/51 (0%) | --- |

| Local inflammation | 0/53 (0%) | 0/51 (0%) | --- |

| Expiration date | 33/53 (62%) | 36/51 (71%) | 0.094 |

| Central venous access | |||

| Immediate removal after peripheral venous access placement | 52/56 (93%) | 52/55 (95%) | 1.000 |

| Duration of the central venous access (days) | 7 (3.75–12.25) | 7 (5–11) | |

| Localisation of the catheter | 0.046 | ||

| Femoral | 4/54 (07%) | 13/56 (23%) | |

| Jugular | 48/54 (89%) | 42/56 (75%) | |

| Subclavian | 2/54 (4%) | 1/56 (2%) | |

| Colonisation | 6/51 (12%) | 7/51 (14%) | 1.000 |

*Comparisons between groups were performed using the χ² test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon test for quantitative variables.

†One case lost.

‡One patient presented an unexpected clinical deterioration before the first attempt.

Nurse and patient satisfaction

Patient satisfaction at the time of success did not significantly differ between the two groups (UGM (median (IQR): 8 (7–9) vs LM: 8 (7–9.5), p=0.543). Reported nurse satisfaction revealed that, compared with the LM, the UGM was (1) more suitably adapted for the clinical setting than the LM (p<0.001), (2) time-saving (p=0.018) and (3) associated with an a priori better PIVC quality (p=0.017) (online supplementary data material 4, table S2).

bmjopen-2017-020220supp002.pdf (55.1KB, pdf)

Sensitivity analysis to maintain intention to treat principle

Since one patient had no clinical data due to the loss of his clinical file in the UGM group and one patient presented an unexpected clinical deterioration before attempting any puncture, a sensitivity analysis was performed in order to strictly apply the intention-to-treat analysis principle. In the first sensitivity analysis, the best-case scenario was considered (ie, that success would be achieved at the first attempt in this patient randomised to the UGM group and that failure would have occurred at the 12th attempt in the LM group); The Mann-Whitney p-value for the primary outcome was 0.678 (attempts: 2 (1–4) in the UGM group and 2 (1–4) in the LM group). Similar results were observed using the worst-case scenario method (ie, that failure would have occurred at the 12th attempt in the UGM group and that success would be achieved after the first attempt in the LM group; attempts: 2 (1–4) in the UGM group and 2 (1–4) in the LM group, p=0.914. Using the imputation with a median of 2 for the two-lacking data yielded similar results (p=0.877).

Discussion

In the present study, fluid overload with stasis oedema was the main reason for an anticipated difficult PIVC at the end of patient stay in ICU. In this setting, UGM did not decrease the number of attempts for PIVC placement. However, of note, catheters in the UGM group tended to be larger and be associated with more extravasation.

The selected population is a major strength of this study. Similarly to Kerforne et al, we describe a prospective population with true anticipated difficulties for PIVC placement marked by >80% stasis oedema and 30% obesity with a body mass index >30 kg/m2.9 This high rate of stasis oedema is a direct consequence of the severity of the population with high SAPS II at admission as well as high proportions of infused catecholamines and renal replacement therapy. Other studies had already demonstrated that a higher cumulative fluid balance was associated with greater disease severity and poor outcome, particularly during septic shock.10

Particular emphasis was given on nurse training in this study. Compared with other published studies, the entire paramedical team was trained, such that after 1 year of training, 70% of the critical care nurses had acquired the UGM. The remaining 30% represented those with less than 1 year seniority (not allowed to participate) as well as usual team turnover. This high training rate is similar to the current situation at bedside in Europe where physicians are most often not involved in PIVC placement and where there is no technician specialist as those described in the McCarthy et al study.6 7 This approach allowed patients to be randomised by critical care nurses on a 24 hours a day, 7 days a week basis. However, due to restrictive inclusion criteria, the inclusion rate was only 1/10 patients.

Finally, prior multiple attempts with the LM was not an inclusion criterion in this study, thus avoiding the risk of selection bias found in nearly all other studies.2–7

Our findings show that there was no decrease in the number of attempts between the two methods. The number of attempts per day of attempt was also of importance since successive failures could have influenced placement success in the ensuing attempts and thus the primary outcome. It should be remembered that in the present population, the venous network was altered by the prolonged ICU stay. The impact of three failed attempts was logically a reduction in the number of available vessels for the next day of attempt.

The observed success rate after three attempts was 66% in the UGM group and 70% in the LM group. In the Bahl et al study conducted in the emergency department by emergency nurses with a very similar methodology, the success rate was higher at 76% in the UGM group and lower at 56% in the LM group after only two attempts.8 In an intensive care setting, Kerforne et al also found a higher success rate in the UGM group after two attempts at 70%.9 The lower success rate in the UGM group in the present study is not surprising considering that our specific population differed from patients admitted to the emergency department and was more difficult to cannulate than those in previously published studies. The success rate in the LM was only 33% at the first attempt but reached 70% after three attempts on the first day. We can only hypothesise that compared with the emergency setting, critical care nurses had more time at their disposal to place the PIVC.

Although there were no differences in the primary outcome between the two techniques, it is worth noting that, in the UGM group, catheters were larger with no impact on catheter lifespan compared with the LM group.

Extravasation tended to be more frequent in the UGM group likely due to insufficiently long catheters for the deep veins of the punctured arm. Some authors have logically suggested that one size does not fit all and thus recommend the use of midline catheters, which are associated with a lower risk of dislodgment and extravasation. Such strategy in this specific ICU population using the UGM and midline catheters needs to be assessed in a future clinical trial.

We did not observe any differences between the two groups with regard to central venous catheter duration and colonisation at removal. However, with an annual rate of catheter infection below 5/1000 patients in our unit, finding any difference between the two groups was unlikely given our sample size.

Patient satisfaction is typically assessed in this type of study.2 7 Not surprisingly, given the perspective of leaving the ICU as well as the similar number of attempts between the two techniques, patient satisfaction was high in both groups.

As specified above, the strength of our study was a randomised but pragmatic design including a protocol entirely conducted by the critical care nurses that actually perform PIVC placement. Hence, in essence, physicians were not involved in any part of patient inclusion aside from the handing of the information notice. Moreover, selection bias was prevented by excluding any prior attempt with the LM before inclusion.

This study has several limitations. First, this is a single-centre randomised study, reflecting our bedside practices and thus no external validation could be performed. The main limitation of this study was the potential insufficient nurse training resulting in differing skill levels for operators. Indeed, some could argue that four successful placements with the UGM do not represent sufficient training and that significant improvement would have been observed in a training module with seven to ten attempts. Consequently, differences in nurse skill level between the two groups could have acted as a confounding factor. We also stated that the length of the catheters used (1.16 inches) was too short to cannulate deep veins in the UGM group. This was associated with more extravasation. To strengthen the diagnosis of stasis oedema and support our hypothesis between catheter length and extravasation in UGM group, measuring vessel depth prior to attempts with the UGM would have been preferable. Unfortunately, such measurement was not performed and could likely represent a major limitation of this study. Finally, some authors have reported the use of longer 1.75-inch or 1.88-inch catheters for the placement of PIVC with UGM.11 Another limitation is the statistical power of the present study. Indeed, we expected a greater number of attempts with the LM than that ultimately observed. Although unlikely, given the similar results, sample size may have been insufficient.

Conclusion

In intensive care patients with no visible or palpable veins due to stasis oedema or overweight, there was no decrease in the number of attempts with an UGM compared with the LM for the placement of PIVC by trained critical care nurses. However, with the former technique, catheters tended to be larger and be associated with higher extravasation, despite the lack of vessel depth measurement. Nurse training remains the cornerstone of an ultrasound-guided PIVC programme, which could have been insufficient in the present study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Pierre Pothier for the editing of the manuscript. We deeply thank the paramedical team of the Nancy Brabois ICU, which included day and night patients in this work.

Footnotes

Contributors: CB, BL and AK designed the study, performed data interpretation and the writing of the manuscript. NT recorded the data. TL, AM-R and MM included patients. CB and NG performed the statistical analysis and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding: CB received a grant from the French Intensive Care Society: ‘Bourse Recherche Paramédicale 2016’.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: CPP EST III.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data are available on reasonable request from CB and NG.

References

- 1. Miliani K, Taravella R, Thillard D, et al. Peripheral venous catheter-related adverse events: evaluation from a multicentre epidemiological study in France (the CATHEVAL Project). PLoS One 2017;12:e0168637 10.1371/journal.pone.0168637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Weiner SG, Sarff AR, Esener DE, et al. Single-operator ultrasound-guided intravenous line placement by emergency nurses reduces the need for physician intervention in patients with difficult-to-establish intravenous access. J Emerg Med 2013;44:653–60. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.08.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aponte H, Acosta S, Rigamonti D, et al. The use of ultrasound for placement of intravenous catheters. Aana J 2007;75:212–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Costantino TG, Kirtz JF, Satz WA. Ultrasound-guided peripheral venous access vs. the external jugular vein as the initial approach to the patient with difficult vascular access. J Emerg Med 2010;39:462–7. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2009.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Costantino TG, Parikh AK, Satz WA, et al. Ultrasonography-guided peripheral intravenous access versus traditional approaches in patients with difficult intravenous access. Ann Emerg Med 2005;46:456–61. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McCarthy ML, Shokoohi H, Boniface KS, et al. Ultrasonography versus landmark for peripheral intravenous cannulation: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med 2016;68:10–18. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stein J, George B, River G, et al. Ultrasonographically guided peripheral intravenous cannulation in emergency department patients with difficult intravenous access: a randomized trial. Ann Emerg Med 2009;54:33–40. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.07.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bahl A, Pandurangadu AV, Tucker J, et al. A randomized controlled trial assessing the use of ultrasound for nurse-performed IV placement in difficult access ED patients. Am J Emerg Med 2016;34:1950–4. 10.1016/j.ajem.2016.06.098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kerforne T, Petitpas F, Frasca D, et al. Ultrasound-guided peripheral venous access in severely ill patients with suspected difficult vascular puncture. Chest 2012;141:279–80. 10.1378/chest.11-2054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sakr Y, Rubatto Birri PN, Kotfis K, et al. Higher fluid balance increases the risk of death from sepsis: results from a large international audit. Crit Care Med 2017;45:386–94. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Duran-Gehring P, Bryant L, Reynolds JA, et al. Ultrasound-guided peripheral intravenous catheter training results in physician-level success for emergency department technicians. J Ultrasound Med 2016;35:2343–52. 10.7863/ultra.15.11059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-020220supp003.pdf (70.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-020220supp004.pdf (48.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-020220supp001.pdf (47.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-020220supp002.pdf (55.1KB, pdf)