Abstract

Objective

To develop and internally validate a prediction model for tinnitus recovery following unilateral cochlear implantation.

Design

A cross-sectional retrospective study.

Setting

A questionnaire concerning tinnitus was sent to patients with bilateral severe to profound hearing loss, who underwent unilateral cochlear implantation at the University Medical Center Utrecht, the Netherlands, between 1 January 2006 and 31 December 2015.

Participants

Of 137 included patients, 87 patients experienced tinnitus preoperatively. Data of these 87 patients were used to develop the prediction model.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The outcome of the prediction model was tinnitus recovery. Investigated predictors were: age, gender, duration of deafness, preoperative hearing performance, tinnitus duration, severity and localisation, follow-up duration, localisation of cochlear implant (CI) compared with tinnitus side, surgical approach, insertion depth of the electrode, CI brand and difference in hearing threshold following cochlear implantation. Multivariable backward logistic regression was performed. Missing data were handled using multiple imputation. The performance of the model was assessed by the calibrative and discriminative ability of the model. The prediction model was internally validated using bootstrapping techniques.

Results

The tinnitus recovery rate was 40%. A lower preoperative Consonant-Vowel-Consonant (CVC) score, unilateral localisation of tinnitus and larger deterioration of residual hearing at 250 Hz revealed to be relevant predictors for tinnitus recovery. The area under the receiver operating characteristics curve (AUC) of the initial model was 0.722 (IQR: 0.703–0.729). After internal validation of this prediction model, the AUC decreased to 0.696 (IQR: 0.667–0.700).

Conclusion and relevance

Lower preoperative CVC score, unilateral localisation of tinnitus and larger deterioration of residual hearing at 250 Hz were significant predictors for tinnitus recovery following unilateral cochlear implantation. The performance of the model developed in this retrospective study is promising. However, before clinical use of the model, the conduction of a larger prospective study is recommended.

Keywords: tinnitus, cochlear implantation, cochlear implant, prediction model

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to develop and internally validate a prediction model for tinnitus recovery following unilateral cochlear implantation.

A robust method, multivariable prediction model with internal validation, was used to thoroughly examine a wide range of clinically useful predictors.

The retrospective study design could have led to certain types of bias (eg, recall bias, non-response bias). Also, a quantitative measure of preoperative tinnitus severity is lacking.

This study has a relatively high sample size when compared with previous studies on tinnitus recovery following cochlear implantation, however, for the development of a prediction model, the sample size is relatively low, and therefore we had to conduct a strong selection procedure for potential predictors.

Introduction

Tinnitus is a common problem, but uncertainty exists about its true prevalence. Estimates range between 5% and 43%.1 The exact cause of tinnitus is unknown. In the majority of the individuals, tinnitus is accompanied by sensorineural hearing loss.2 3 Currently, standard clinical care for adult patients with bilateral severe to profound sensorineural hearing loss is unilateral cochlear implantation.4 Prevalence rates of preoperative tinnitus in cochlear implant (CI) patients range from 66% to 86%.5

Partial or complete suppression of tinnitus is often reported as a beneficial side effect of cochlear implantation.6 A recent systematic review reported recovery (complete suppression) of tinnitus in 8%–45% of patients and a decrease of tinnitus in 25%–72% of patients with preoperative tinnitus.6 However, an increase of tinnitus burden was also reported in 0%–25% of patients. Even newly induced tinnitus after cochlear implantation can occur in 0%–20% of patients without preoperative tinnitus.6–9 Cochlear implantation as a single treatment for invalidating tinnitus with or without unilateral sensorineural hearing loss is still part of debate in the literature.10

Which CI patients with preoperative tinnitus will recover from tinnitus after cochlear implantation and which patients will not, is barely investigated. A prediction model for tinnitus recovery following cochlear implantation to identify these different groups, would be of great importance. First, a prediction model would enable clinicians to counsel patients preoperatively about the expectations regarding their tinnitus recovery. Second, knowledge about predictive factors that can be influenced could lead to adjustments in the patient’s lifestyle or treatment strategy in order to increase the chance of tinnitus recovery.

To date, only few studies investigated possible predictors for tinnitus improvement following cochlear implantation. The prospective study of Kim et al 11 did this as a secondary analysis of their study. Three factors significantly predicted tinnitus outcome: the preoperative auditory steady-state response, which is an electrophysiological test that evaluates hearing thresholds, the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI) score, which indicates tinnitus severity and the final Beck’s Depression Index (BDI) score, which indicates depression severity.11 No information was given on the performance of this model and this model was not internally or externally validated. The study of Pan et al 12 tried to identify differences between patients with and without tinnitus recovery, but no clear differences were found.12

A study conducting, developing and validating a multivariable clinical prediction model is lacking. Therefore, the aim of the current study was to develop and internally validate a clinical model that predicts tinnitus recovery following unilateral cochlear implantation in patients with bilateral severe to profound hearing loss and preoperative tinnitus.

Methods

We conducted and reported this study using the transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD) statement.13

The 10-year results concerning prevalence rates of tinnitus in our centre are previously reported using the same database as the current study (Ramakers et al, submitted, 2017).

This study was designed and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.14 All included participants provided written informed consent.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and public were not involved in the development or design of this study.

Study design and participants

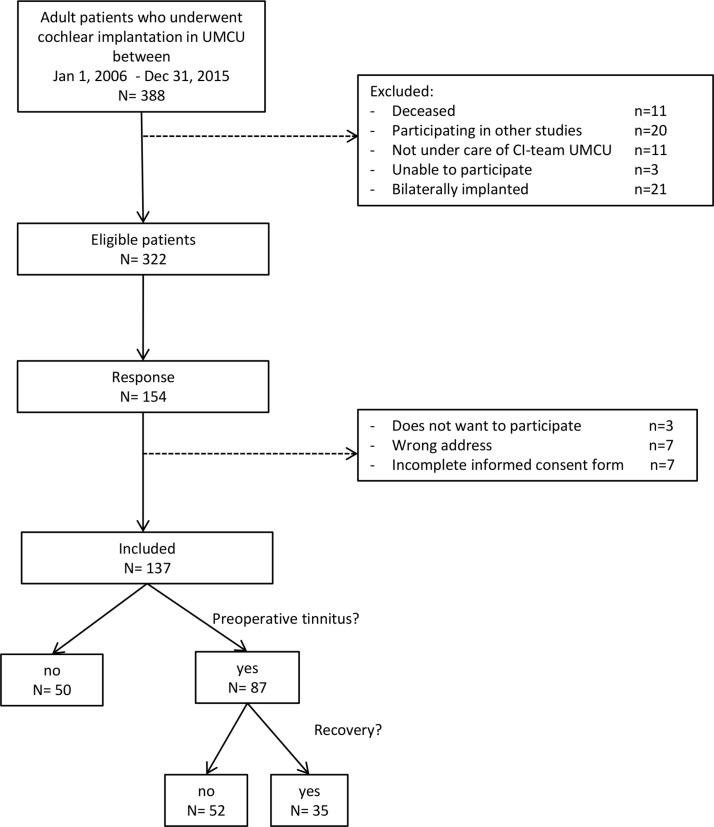

This retrospective study was conducted at the Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery from the UMCU. A self-developed questionnaire (see online supplementary file) was sent out to all adult patients with bilateral severe to profound hearing loss who underwent unilateral cochlear implantation between 1 January 2006 and 31 December 2015, who were still under care of the UMCU and had at least 6-month experience with the CI. Patients were first approached in June 2016. The patients who did not answer the first invitation received a second invitation for participation in August 2016. For all patients who returned the completed informed consent form and questionnaire, additional patient information needed for the prediction model was extracted from the medical file. The flow chart of the study is presented in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study. CI, cochlear implant; UMCU, University Medical Center Utrecht.

bmjopen-2017-021068supp001.pdf (186.8KB, pdf)

Outcome

The outcome that is predicted by the prediction model is tinnitus recovery after cochlear implantation. Tinnitus recovery was defined as the presence of tinnitus preoperatively and complete absence of tinnitus postoperatively at the moment of completing the questionnaire. Complete absence was defined as absence of tinnitus in all situations: when the CI was switched ‘on’ and ‘off’. The presence of tinnitus preoperatively was assessed in a standard preoperative checklist and collected from the medical file. The presence of tinnitus postoperatively was assessed with the questionnaire.

Potential predictors

Potential predictors based on clinical relevance and literature included a wide range of demographic, deafness-related, tinnitus-related and surgery-related factors.8 11 15 Information concerning these possible predictors was collected from the medical file and information not available in the medical file was collected with the questionnaire.

Demographic factors, age at time of surgery and gender, were collected from the medical file.

Deafness-related factors were extracted from the medical file and included prelinguality, duration of deafness, aetiology of deafness and preoperative and postoperative hearing performance. Hearing performance was measured using two hearing tests: the Consonant-Vowel-Consonant (CVC) test, which results in a percentage correct score (a higher score reflects a better hearing performance) and audiometric hearing thresholds measured by pure-tone audiometry (PTA) at frequencies 125, 250, 500, 1000, 2000, 4000, 8000 Hz, which results in a threshold per frequency in decibel hearing level (dBHL). If a frequency was not heard by the patient, a threshold value of 130 dBHL was used as cut-off value (Ramakers et al, submitted, 2017).

Tinnitus-related factors collected with the questionnaire were: preoperative tinnitus duration, tinnitus severity (mild/moderate/severe) and tinnitus-related comorbidity as depression and anxiety. The localisation of tinnitus was asked in a standard preoperative checklist and collected from the medical file.

Surgery-related factors were extracted from the medical file and included the time between surgery and completing the questionnaire (follow-up duration), localisation of CI compared with tinnitus side, surgical approach (cochleostomy or round window), full or partial insertion of the electrode, brand of CI and deterioration of hearing after surgery. Deterioration of hearing was defined as difference in hearing threshold after surgery per frequency in the operated ear (pure-tone threshold shortly after surgery minus threshold shortly before surgery).8 11 15

Missing data

Outcome: There were no missings in preoperative tinnitus data. Eight patients were contacted by telephone to solve the missings in retrospectively collected data concerning postoperative tinnitus presence.

Predictors: Duration of tinnitus was missing in 45%, severity of tinnitus was missing in 28%, surgical approach in 6%, preoperative CVC score in 2%, difference in thresholds at 250–8000 Hz in 12% and difference at 125 Hz in 13% of patients.

The Little’s missing completely at random (MCAR) test and independent t-tests and X2 tests with missing data indicator as group variable were used to differentiate between MCAR and not MCAR data. Our missing data was most likely MCAR for the variables surgical approach and preoperative CVC score and most likely missing at random for the duration of tinnitus, severity of tinnitus and the hearing thresholds.16 In either way, multiple imputation is a decent method.16 Therefore, multiple imputation was performed for all of above-mentioned predictor variables with missing data using the multivariate imputation by chained equation procedure with the predictive mean matching method. Variables with more than 40% missing data were only imputed and not used as predictor. Fifteen multiple imputed datasets were created, as the total percentage of missing observations was about 15%. All results from the pooled dataset are reported. Rubin’s rules were used to pool the regression coefficient estimates from the imputed datasets. As a sensitivity analysis, the results of the original dataset with missing data are also reported.

Statistical methods

Baseline characteristics of patients with and without tinnitus recovery were presented. Normally distributed data were presented as mean and SD, not normally distributed data were presented as median and IQR.

For the final prediction model, we attempted to not cross the 10 event/non-events per predictor variable (EPV) criterion.17 Therefore, we first selected the most important potential predictors based on clinical relevance, literature and the baseline descriptives. Univariable logistic regression with the remaining predictors as covariate and tinnitus recovery (no=0, yes=1) as the dependent variable was performed afterwards. As recommended in the TRIPOD statement, Akaike’s information criterion (p<0.157) was used to select a predictor after univariable screening. The most relevant predictors after univariable screening were used in the final multivariable logistic regression model and backward stepwise selection was applied for removal of a predictor (p<0.157). In case there was multicollinearity between variables, the variable with the best predictive value (ie, combination of p value and type of predictor variable) was selected.

The performance of a prediction model can be assessed by the calibrative and discriminative ability of the model. Calibration refers to the agreement between the predicted outcomes and the observed outcomes.18 19 A calibration curve will present the predicted and observed probabilities for deciles of patients in the first imputed dataset.19 The calibration will also be assessed with the Hosmer and Lemeshow test for goodness of fit in all imputed datasets and the range of p values is reported. A p>0.05 means a good fit of the model, as it indicates that there is no significant difference between the predicted and observed outcomes. The discrimination of the model is the ability of the model to distinguish between patients who did recover from tinnitus and patients who did not recover from tinnitus.18 The discrimination will be assessed with the area under the receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve (AUC) in each imputed dataset and the median AUC with IQR will be reported.20 An AUC ranges from 0.5 (no discrimination above chance) to 1 (perfect discrimination).

Especially in small datasets, there is a high chance that the prediction model is overfitted, that is, too much adapted to the data. To adjust the prediction model for overfitting, bootstrapping techniques (250 bootstraps) were used, which is called internal validation. This procedure generates a calibration slope that can be used to adjust the regression coefficients (and indirect the ORs) and the AUC.20

R V.3.0.3 was used for the internal validation, IBM SPSS Statistics V.22.0 was used for all other analyses.

Results

Participants

Between 1 January 2006 and 31 December 2015, 322 eligible patients underwent unilateral cochlear implantation in the UMCU (figure 1). Eventually, 137 patients were included in this study. All patients received a CI because of severe to profound hearing loss and the presence or severity of tinnitus were not part of the indication criteria. The prevalence of preoperative tinnitus was 64%. The data of these 87 patients were used to develop the prediction model. The recovery rate of tinnitus was 40%. Worsening of tinnitus in the years after surgery was reported by 9 (10%) patients

Prediction model

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of the patients with and without tinnitus recovery. The median follow-up period was 5.3 (IQR: 2.4–7.1) years in the patients with tinnitus recovery and 3.5 (IQR: 1.5–6.1) years in the patients without tinnitus recovery.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with and without recovery of preoperative tinnitus

| Recovery (n=35) | No recovery (n=52) | |

| Demographics | ||

| Age in years, median (IQR) | 67.7 (58.3–71.2) | 60.0 (51.7–66.2) |

| Male, n (%) | 20 (57) | 26 (50) |

| Deafness-related factors | ||

| Prelinguality, n (%) | 3 (9) | 3 (6) |

| Duration of deafness-operated ear in years, median (IQR) | 9.7 (2.1–34.6) | 10.3 (2.5–23.1) |

| Aetiology of deafness-operated ear, n (%) | ||

| Progressive | 18 (51) | 17 (33) |

| Congenital | 3 (9) | 6 (12) |

| Meningitis | 1 (3) | 3 (6) |

| Postnatal infection | 4 (11) | 5 (10) |

| Traumatic | 1 (3) | 3 (6) |

| Otosclerosis | 2 (6) | 5 (10) |

| Sudden deafness | 0 (0) | 3 (6) |

| Menière’s disease | 5 (14) | 9 (17) |

| Iatrogenic | 1 (3) | 1 (2) |

| Preoperative CVC score, median (IQR) | 33.0 (0.0–58.0) | 45.0 (24.3–64.0) Missing: 2 |

| Preoperative PTA threshold operated ear in dBHL, mean (SD) | 100.8 (16.8) Missing: 1 |

106.7 (17.3) Missing: 1 |

| Tinnitus-related factors | ||

| Tinnitus duration preoperative in years, median (IQR) | 10.0 (4.6–16.3) Missing: 25 |

17.3 (10.0–30.0) Missing: 14 |

| Tinnitus severity preoperative, n (%) | ||

| Mild | 2 (14) | 13 (27) |

| Moderate | 7 (50) | 19 (39) |

| Severe | 5 (36) Missing: 21 |

17 (35) Missing: 3 |

| Localisation tinnitus, n (%) | ||

| Right ear | 6 (17) | 4 (8) |

| Left ear | 9 (26) | 7 (13) |

| Bilateral | 20 (57) | 41 (79) |

| Depression preoperative, n (%) | 2 (6) | 3 (6) Missing: 1 |

| Anxiety preoperative, n (%) | 1 (3) Missing: 1 |

2 (4) Missing: 1 |

| Surgery-related factors | ||

| Follow-up duration in years, median (IQR) | 5.3 (2.4–7.1) | 3.5 (1.5–6.1) |

| Localisation cochlear implant versus tinnitus, n (%) | ||

| Cochlear implant contralateral to tinnitus side | 9 (26) | 4 (8) |

| Cochlear implant ipsilateral to tinnitus side | 6 (17) | 7 (13) |

| Unilateral cochlear implant, bilateral tinnitus | 20 (57) | 41 (79) |

| Surgical approach, n (%) | ||

| Cochleostomy | 26 (74) | 36 (69) |

| Round window | 8 (23) Missing: 1 |

12 (23) Missing: 4 |

| Insertion, n (%) | ||

| Full | 34 (97) | 46 (88) |

| Partial | 1 (3) | 6 (12) |

| Brand cochlear implant, n (%) | ||

| Cochlear | 13 (37) | 25 (48) |

| MedEl | 17 (49) | 23 (44) |

| Advanced Bionics | 5 (14) | 4 (8) |

| Postoperative CVC in percentage score, median (IQR) | 83.3 (52.0–88.0) | 85.9 (78.2–94.0) |

| Difference in PTA threshold operated ear in dBHL, median (IQR) | 25.7 (9.4–37.0) Missing: 3 |

16.6 (4.3–28.4) Missing: 8 |

PTA: average threshold over frequencies 0.125–8 kHz.

CVC, Consonant-Vowel-Consonant test; dBHL, decibel hearing level; PTA, pure-tone average.

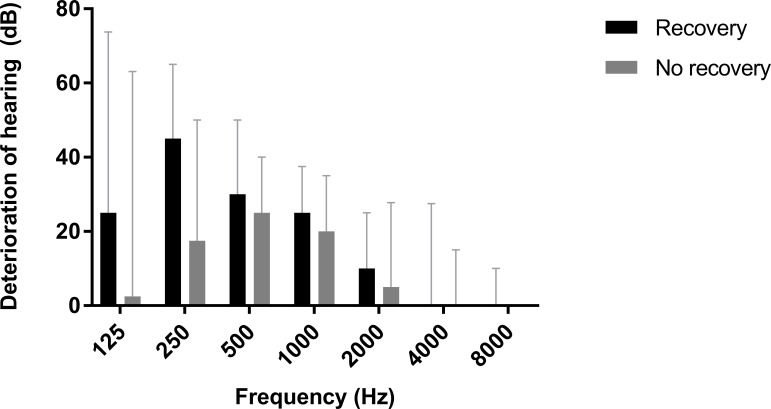

The prevalences of prelinguality and tinnitus-related comorbidity were very low in both groups and therefore these variables were not further investigated. The aetiology of deafness was a variable with a lot of categories and low prevalences in many categories, therefore, this variable was not further investigated. Figure 2 presents the deterioration in hearing thresholds per frequency for both groups. As the largest differences between groups were seen at the low frequencies (125–1000 Hz), only these frequencies were further investigated as potential predictors (table 2).

Figure 2.

Deterioration of hearing in the operated ear after cochlear implantation for patients with and without tinnitus recovery. Medians with IQR are presented.

Table 2.

Univariable logistic regression between predictor variables and tinnitus recovery (results of pooled analyses after multiple imputation) (n=87)

| Predictor | OR (95% CI) | P values |

| Demographics | ||

| Age | 1.033 (0.997 to 1.071) | 0.075 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | Ref | Ref |

| Male | 0.750 (0.317 to 1.777) | 0.513 |

| Deafness-related factors | ||

| Duration of deafness-operated ear | 1.004 (0.982 to 1.027) | 0.738 |

| Preoperative CVC score | 0.986 (0.971 to 1.003) | 0.101 |

| Tinnitus-related factors | ||

| Tinnitus duration | 0.964 (0.912 to 1.019) | 0.193 |

| Tinnitus severity | ||

| Mild | Ref | Ref |

| Moderate | 0.776 (0.118 to 5.112) | 0.787 |

| Severe | 0.690 (0.086 to 5.573) | 0.720 |

| Localisation tinnitus | ||

| Unilateral | Ref | Ref |

| Bilateral | 0.358 (0.139 to 0.919) | 0.033 |

| Surgery-related factors | ||

| Follow-up duration | 1.100 (0.944 to 1.283) | 0.223 |

| Localisation cochlear implant versus tinnitus | ||

| Cochlear implant contralateral to tinnitus side | Ref | Ref |

| Cochlear implant ipsilateral to tinnitus side | 0.381 (0.077 to 1.896) | 0.239 |

| Unilateral cochlear implant, bilateral tinnitus | 0.217 (0.059 to 0.790) | 0.021 |

| Surgical approach | ||

| Cochleostomy | Ref | Ref |

| Round window | 0.921 (0.329 to 2.576) | 0.876 |

| Insertion | ||

| Partial | Ref | Ref |

| Full | 4.435 (0.510 to 8.567) | 0.177 |

| Brand cochlear implant | ||

| Cochlear | Ref | Ref |

| MedEl | 1.421 (0.568 to 3.558) | 0.453 |

| Advanced Bionics | 2.404 (0.550 to 0.515) | 0.244 |

| Difference hearing threshold at 125 Hz | 1.005 (0.993 to 1.017) | 0.444 |

| Difference hearing threshold at 250 Hz | 1.015 (0.999 to 1.031) | 0.071 |

| Difference hearing threshold at 500 Hz | 1.006 (0.987 to 1.026) | 0.533 |

| Difference hearing threshold at 1000 Hz | 1.012 (0.986 to 1.038) | 0.374 |

OR >1: in favour of tinnitus recovery.

P values <0.157 (Akaike’s criterion) are presented in bold.

CVC, Consonant-Vowel-Consonant test; Ref, reference.

Age, preoperative CVC score, tinnitus localisation, localisation of CI compared with tinnitus side and the difference in hearing threshold measured at 250 Hz appeared to be the most relevant predictors after univariable logistic regression analyses of all potential predictors (table 2).

Since the predictors ‘tinnitus localisation’ and ‘localisation of CI compared with tinnitus’ were collinear, the ‘tinnitus localisation’ was chosen for the final analysis. After applying stepwise backward regression analysis with the remaining predictors, preoperative CVC score (OR 0.978; 95% CI 0.958 to 0.999), bilateral tinnitus (OR 0.412; 95% CI 0.151 to 1.124) and difference in 250 Hz (1.024, 95% CI 1.004 to 1.044) were the strongest predictors for tinnitus recovery (table 3). Backward regression analysis in the original dataset without missing data revealed similar results (table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariable logistic regression model for the prediction of tinnitus recovery following unilateral cochlear implantation (in the pooled dataset and in the original dataset as sensitivity analysis)

| Predictor | Pooled dataset (15 multiple imputed sets) (n=87) | Original dataset (complete cases) (n=76) | ||||

| OR (adjusted OR) | 95% CI | P values | OR | 95% CI | P values | |

| Preoperative CVC score | 0.978 (0.983) | 0.958 to 0.999 | 0.038 | 0.978 | 0.957 to 0.999 | 0.042 |

| Bilateral tinnitus preoperative | 0.412 (0.501) | 0.151 to 1.124 | 0.083 | 0.490 | 0.171 to 1.402 | 0.184 |

| Difference audiometry at 250 Hz | 1.024 (1.019) | 1.004 to 1.044 | 0.017 | 1.024 | 1.005 to 1.044 | 0.013 |

OR >1: in favour of tinnitus recovery.

Prediction rule of the pooled dataset after internal validation: linear predictor=0247-(0.017*preoperative CVC score)-(0.691*bilateral tinnitus)+(0.019*difference in hearing threshold at 250 Hz).

Adjusted OR: OR corrected for overoptimism after internal validation; CVC, Consonant-Vowel-Consonant test.

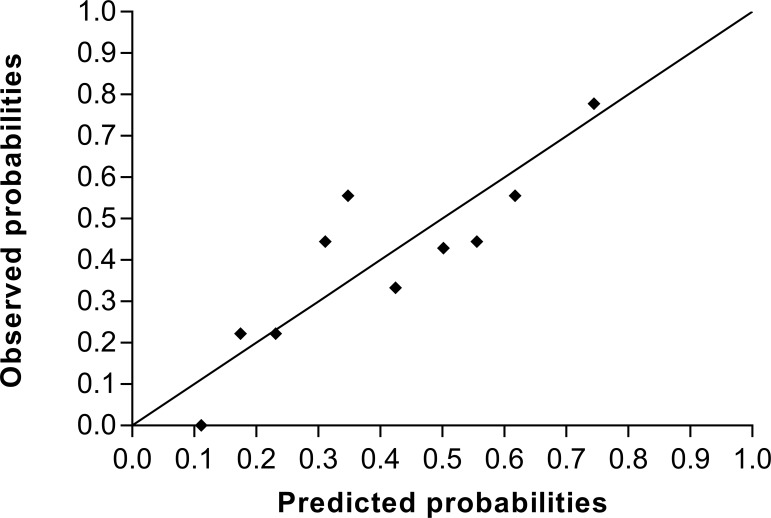

Model performance

The Hosmer and Lemeshow test for goodness of fit was not significant in all the imputed datasets with a p value range between 0.121 and 0.705. Figure 3 shows the calibration curve of the predicted and observed probabilities of tinnitus recovery. The median AUC was 0.722 (IQR: 0.703–0.729).

Figure 3.

The frequencies of observed outcomes for 10th of predicted probabilities. Results from the first imputed dataset.

In the original dataset with missing data the Hosmer and Lemeshow test was also not significant with a p value of 0.383 and the AUC was 0.711 (95% CI 0.595 to 0.826).

Internal validation

The mean slope shrinkage factor after bootstrapping in all the imputed datasets was 0.779 (SE:0.007). This led to adjusted ORs for all the predictors (table 3). The median AUC of the model decreased to 0.696 (IQR: 0.667–0.700).

Discussion

Key findings

The current study used retrospective data to identify predictors for tinnitus recovery following unilateral cochlear implantation. Recovery of tinnitus was more common in patients with a lower preoperative CVC score, unilateral localisation of tinnitus and larger deterioration of residual hearing at 250 Hz.

Comparison with literature

In the relatively small study population (n=40) of Kim et al, a higher preoperative THI score (indicating more severe tinnitus) predicted a larger change in THI score postoperatively.11 In the current study, preoperative tinnitus severity was not indicated as a predictor for tinnitus recovery. An explanation for these contradictive results could be the measurement of tinnitus severity in the current study which was retrospectively measured with a multiple choice question instead of a validated tinnitus severity questionnaire. The retrospective design could have led to recall bias and therefore underestimation or overestimation of the preoperative tinnitus severity in the patients with tinnitus recovery. Also, the percentage of missings in preoperative tinnitus severity was high in the recovery group in the current study, which could have led to biased results.

A lower final BDI score (indicating less severe depression) was another predictor reported by Kim et al.11 This finding corresponds with previous literature on the correlation between tinnitus severity and depression.7 15 The current study did not investigate depression severity. Only the presence of depression was measured. Due to the low prevalence of depression, however, the current study does not allow conclusions regarding the predictive value of this variable.

Strengths and weaknesses of this study

To our knowledge, this is the first study with the primary aim to develop and internally validate a multivariable prediction model for tinnitus recovery following unilateral cochlear implantation. A wide range of clinically useful possible predictors was investigated. Another strength of our study is the internal validation of the prediction model using bootstrapping techniques. Also, missing data were handled using multiple imputation.

A limitation of this study is the retrospective study design, which could have resulted in recall bias by the relatively long follow-up period. We tried to minimise recall bias by using the prospectively measured data concerning preoperative tinnitus outcome. However, information concerning possible predictors was retrospectively collected. The long recall interval could probably have resulted in an underestimation or overestimation of the tinnitus duration and tinnitus severity. This could have resulted in an underestimation or overestimation of the predictive values of these predictors. Furthermore, patients were not asked about the exact time of the tinnitus recovery, because we assumed this would be unreliable due to the long interval. This withheld us from drawing conclusions about the time course of recovery following cochlear implantation. Also, the follow-up duration was different in both study groups, however, univariable regression analysis showed this was not a significant predictor for tinnitus recovery.

Another possible limitation of this study is the selection of the included patients. Only 137 of 322 eligible patients (43%) were included. Non-response bias could have occurred. We tried to minimise this bias by sending a reminder to the patients who did not respond after the first invitation. We were not able to determine differences between responders and non-responders.

Furthermore, we were not able to determine the exact hearing threshold per frequency with the current audiometry. Therefore, a cut-off value of 130 dBHL for all frequencies was used when a tone was not heard by the patient. It is questionable whether 130 dBHL is the correct cut-off value to use and whether it is correct to use the same cut-off value for all frequencies.

Another limitation of this study is the relatively small sample size. According to the EPV criterion, we could perform a backward logistic regression analysis with a maximum of three variables. With the use of four predictors in the initial prediction model, the limit of three was exceeded. A recent study, however, concluded that the evidence for the maximum of 10 EPV is weak and since the final model in the current study is stable, we think the exceedance did not influence the quality of the model.21 Moreover, the list of potential predictors was relatively long and therefore we used univariable screening of predictors to identify the most important predictors. This approach could have led to the missing of a predictor that was not significant univariably, but would be significant in the multivariable analysis.

Although we investigated a long list of potential predictors, it is likely that some potentially relevant factors were missed or not available in the current study, data related to coding strategies and rehabilitation for example.

Interpretation of predictor findings and implications

We found that tinnitus recovery is higher in patients with a lower preoperative CVC score, unilateral tinnitus and larger deterioration of residual hearing at 250 Hz. In future, these findings could contribute to a better preoperative counselling of CI candidates with tinnitus and possibly lead to adjustments in structure preservation surgical techniques in order to increase the chance of tinnitus recovery.

It is hypothesised that the reduction of tinnitus after cochlear implantation is caused by the restoration of auditory input with the CI.22 23 Another hypothesis for the reduction of tinnitus after cochlear implantation is acoustic masking. These hypotheses could explain the higher odds of tinnitus recovery in patients with unilateral tinnitus compared with patients with bilateral tinnitus, who will have stronger restoration of the pathway or masking in one of the two tinnitus ears. However, univariable logistic regression analysis showed that there was no significant higher odds on tinnitus recovery for patients with unilateral tinnitus who were implanted in the ipsilateral ear compared with patients with bilateral tinnitus. This finding is contradictive to the above-listed hypotheses. A previous study already showed that unilateral cochlear implantation can reduce tinnitus in the ipsilateral, contralateral and both ears in patients with bilateral tinnitus.24

Our study showed that deterioration of residual hearing at 250 Hz is positive for tinnitus recovery after surgery. For hearing performance, however, contradictive results are found: preservation of residual hearing leads to better hearing outcomes after surgery.25 Advances in structure preservation surgical techniques and minimal invasive electrodes during the past years have led to reduction of cochlear trauma and thereby hearing preservation in patients.25 26 However, for the future our finding implies that adjustments are needed in structure preservation surgical techniques in CI candidates with severe tinnitus in order to increase the chance of tinnitus recovery.

The performance of the prediction model developed in this retrospective study is promising. The discrimination was reasonable as determined by an AUC of 0.696. The prediction model uses simple clinical parameters as predictors, which makes the model clinically applicable. However, before clinical use of a prediction model, an AUC >0.75 is advised.27 In order to increase the performance of the current prediction model, we would recommend to conduct a larger prospective study to develop and internally and externally validate a prediction model for tinnitus recovery following unilateral cochlear implantation.

Conclusion

A lower preoperative CVC score, unilateral tinnitus and larger deterioration of residual hearing at 250 Hz were positive predictors for tinnitus recovery after unilateral cochlear implantation. The performance of the prediction model developed in this retrospective study is promising. However, before clinical use of the model, the conduction of a larger prospective study is recommended.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: GGJR: conception and design of the work, acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data and drafting the paper. GAvZ and HGXMT: concept or design of the work, critical revision of the paper. RJS: data interpretation, critical revision of the paper. MWH and IS: data analysis and interpretation, critical revision of the paper.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: An exemption of full review was obtained from the Medical Ethics Committee of the University Medical Center Utrecht (UMCU) (WAG/mb/16/003184). Exemption was obtained because participants had to complete a short questionnaire only and were not subject to procedures or required to follow rules of behaviour.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. McCormack A, Edmondson-Jones M, Somerset S, et al. . A systematic review of the reporting of tinnitus prevalence and severity. Hear Res 2016;337:70–9. 10.1016/j.heares.2016.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lockwood AH, Salvi RJ, Burkard RF. Tinnitus. N Engl J Med 2002;347:904–10. 10.1056/NEJMra013395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baguley D, McFerran D, Hall D. Tinnitus. Lancet 2013;382:1600–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60142-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Copeland BJ, Pillsbury HC. Cochlear implantation for the treatment of deafness. Annu Rev Med 2004;55:157–67. 10.1146/annurev.med.55.091902.105251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Quaranta N, Wagstaff S, Baguley DM. Tinnitus and cochlear implantation. Int J Audiol 2004;43:245–51. 10.1080/14992020400050033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ramakers GG, van Zon A, Stegeman I, et al. . The effect of cochlear implantation on tinnitus in patients with bilateral hearing loss: A systematic review. Laryngoscope 2015;125:2584–92. 10.1002/lary.25370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kloostra FJ, Arnold R, Hofman R, et al. . Changes in tinnitus after cochlear implantation and its relation with psychological functioning. Audiol Neurootol 2015;20:81–9. 10.1159/000365959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Arts RA, Netz T, Janssen AM, et al. . The occurrence of tinnitus after CI surgery in patients with severe hearing loss: A retrospective study. Int J Audiol 2015;54:910–7. 10.3109/14992027.2015.1079930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Farinetti A, Ben Gharbia D, Mancini J, et al. . Cochlear implant complications in 403 patients: Comparative study of adults and children and review of the literature. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis 2014;131:177–82. 10.1016/j.anorl.2013.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mertens G, De Bodt M, Van de Heyning P. Cochlear implantation as a long-term treatment for ipsilateral incapacitating tinnitus in subjects with unilateral hearing loss up to 10 years. Hear Res 2016;331:1–6. 10.1016/j.heares.2015.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kim DK, Moon IS, Lim HJ, et al. . Prospective, Multicenter Study on Tinnitus Changes after Cochlear Implantation. Audiol Neurootol 2016;21:165–71. 10.1159/000445164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pan T, Tyler RS, Ji H, et al. . Changes in the Tinnitus Handicap Questionnaire After Cochlear Implantation. Am J Audiol 2009;18:144–52. 10.1044/1059-0889(2009/07-0042) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Collins GS, Reitsma JB, Altman DG, et al. . Transparent Reporting of a Multivariable Prediction Model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD): The TRIPOD Statement. Eur Urol 2015;67:1142–51. 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.11.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013;310:2191–4. 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hoekstra CE, Wesdorp FM, van Zanten GA. Socio-demographic, health, and tinnitus related variables affecting tinnitus severity. Ear Hear 2014;35:544–54. 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moons KG, Donders RA, Stijnen T, et al. . Using the outcome for imputation of missing predictor values was preferred. J Clin Epidemiol 2006;59:1092–101. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Steyerberg EW, Models CP. Statistics for Biology and Health. New York: Springer, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moons KG, Altman DG, Reitsma JB, et al. . Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD): explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:W1–73. 10.7326/M14-0698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Crowson CS, Atkinson EJ, Therneau TM. Assessing Calibration of Prognostic Risk Scores. 2017;25:1692–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Marshall A, Altman DG, Holder RL, et al. . Combining estimates of interest in prognostic modelling studies after multiple imputation: current practice and guidelines. BMC Med Res Methodol 2009;9:57 10.1186/1471-2288-9-57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. van Smeden M, de Groot JA, Moons KG, et al. . No rationale for 1 variable per 10 events criterion for binary logistic regression analysis. BMC Med Res Methodol 2016;16:163 10.1186/s12874-016-0267-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bovo R, Ciorba A, Martini A. Tinnitus and cochlear implants. Auris Nasus Larynx 2011;38:14–20. 10.1016/j.anl.2010.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Taub E, Uswatte G, Mark VW. The functional significance of cortical reorganization and the parallel development of CI therapy. Front Hum Neurosci 2014;8 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Quaranta N, Fernandez-Vega S, D’elia C, et al. . The effect of unilateral multichannel cochlear implant on bilaterally perceived tinnitus. Acta Otolaryngol 2008;128:159–63. 10.1080/00016480701387173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dalbert A, Huber A, Baumann N, et al. . Hearing preservation after cochlear implantation may improve long-term word perception in the electric-only condition. Otol Neurotol 2016;37:1314–9. 10.1097/MAO.0000000000001193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Eshraghi AA, Ahmed J, Krysiak E, et al. . Clinical, surgical, and electrical factors impacting residual hearing in cochlear implant surgery. Acta Otolaryngol 2017;137:384–8. 10.1080/00016489.2016.1256499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fan J, Upadhye S, Worster A. Understanding receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. CJEM 2006;8:19–20. 10.1017/S1481803500013336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-021068supp001.pdf (186.8KB, pdf)