Abstract

Objectives

We aimed to evaluate the relation of total homocysteine (tHcy) concentrations with systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) levels, and examine the possible modifiers in the association among a general population of Chinese adults.

Design

A cross-sectional study.

Setting

The study was conducted within 21 communities in Lianyungang of Jiangsu province, China.

Participants

A total of 26 648 participants aged ≥35 years and with no antihypertensive drug use were included in the final analysis.

Results

Overall, there was a positive association between tHcy concentrations and SBP (per 5 μmol/L tHcy increase: adjusted β=0.45 mm Hg; 95% CI 0.29 to 0.61) or DBP levels (per 5 μmol/L tHcy increase: adjusted β=0.47 mm Hg; 95% CI 0.35 to 0.59). Compared with participants with tHcy <10 μmol/L, significantly higher SBP levels were found in those with tHcy concentrations of 10 to <15 (adjusted β=0.80 mm Hg; 95% CI 0.32 to 1.28) and ≥15 µmol/L (adjusted β=1.79 mm Hg; 95% CI 1.20 to 2.37; p for trend <0.001). Consistently, significantly higher DBP levels were found in participants with tHcy concentrations of 10 to <15 (adjusted β=0.86 mm Hg; 95% CI 0.49 to 1.22) and ≥15 µmol/L (adjusted β=2.01 mm Hg; 95% CI 1.57 to 2.46; p for trend <0.001), respectively as compared with those with <10 μmol/L. Furthermore, a stronger association between tHcy and SBP (p for interaction=0.009) or DBP (p for interaction=0.067) was found in current alcohol drinkers.

Conclusion

Serum tHcy concentrations were positively associated with both SBP and DBP levels in a general Chinese adult population. The association was stronger in current alcohol drinkers.

Keywords: total homocysteine, blood pressure, hypertension, alcohol drinking

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Our study included a total of 26 648 male and female adults with no antihypertensive drugs usage, by far the largest study of its kind.

We evaluated the association between total homocysteine (tHcy) concentrations and systolic or diastolic blood levels, and examined the potential modifiers in the association among a general adult population.

As a cross-sectional study, we were not able to determine the causal relationship between tHcy and blood pressure levels.

Introduction

Hypertension is one of the major risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD), chronic kidney disease (CKD) and peripheral arterial disease.1 2 By 2025, the global number of adults with hypertension will be 1.56 billion.3 A better understanding of the modifiable risk factors of hypertension is crucial for clinical decision-making and timely management, for it would lead to early detection and prevention, decreasing the huge burden of hypertension and its associated complications.

Previous studies have shown that total homocysteine (tHcy), an intermediate product in the metabolism of methionine, is a controllable risk factor for many chronic diseases, including CVD, stroke and CKD.4–7 The Hordaland Homocysteine Study8 and the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey study9 further found that there was a positive association between tHcy and blood pressure levels. Consistently, Li et al reported that hyperhomocysteinaemia was independently related to the elevated diastolic blood pressure (DBP).10 Another study indicated that hyperhomocysteinaemia was significantly associated with the prevalence of hypertension in males, but not in females in the general adult population of rural Northeast China.11 Recently, a meta-analysis of relevant randomised trials, including 7887 participants, also indicated that folic acid therapy was effective in reducing the blood pressure and tHcy levels among patients with hypertension and hyperhomocysteinaemia.12 However, in the China Stroke Primary Prevention Trial (CSPPT), folic acid therapy had no obvious effect on blood pressures in 20 702 hypertensive participants.13 In fact, Fakhrzadeh et al 14 and Dinavahi et al 15 found no significant association between tHcy and blood pressure levels. Sundström et al 16 found no obvious relationship of tHcy levels with hypertension incidence or blood pressure progression. These results indicate that the relationship of tHcy with blood pressure remains controversial. The possible explanations included the differences in study populations, sample size and the concomitant drugs or diseases within the study populations. More importantly, although it has been suggested that age, sex, body mass index (BMI), smoking, alcohol drinking, fruit and vegetable consumption and life styles may affect the tHcy and blood pressure levels,17 whether these factors could modify the association between tHcy and blood pressure had not been thoroughly investigated in these previous studies.

Therefore, the present study aimed to evaluate the relation of tHcy concentrations with blood pressure levels, and examine the potential modifiers in the association among a general Chinese adult population.

Methods

Study participants

We conducted an epidemiological study for identification, education and register of the high-risk population with both hypertension and elevated tHcy within 21 communities in Lianyungang of Jiangsu province, China, from July 2016 to September 2016. We recruited from the community through open recruitment rather than a random selection. All participants provided written informed consent.

Eligible participants were men and women aged 35 years and older. The lowest age limit was defined as 35 years old in order to improve the recruitment rate of patients with hypertensive. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) individuals with severe mental disorders; (2) individuals with abnormal laboratory tests or clinical manifestations who were unsuitable to participate as judged by the investigators and (3) anyone unwilling to participate in the study.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement was taken into consideration during the whole study. We performed a pilot study to evaluate the feasibility of the project and invited the participants to provide comments. The staff collected the comments of the participants for discussing and further updating the questionnaires and research design. As we have collaborated with local medical institutions to create archives of the participants and established long-term cohorts, our findings are regularly disseminated to the participants and local residents by the local medical institutions.

Data collection and measurements

Baseline data were collected by trained research staff according to standard operating procedure. Face-to-face interviews were conducted using a standardised questionnaire designed specifically for the present study, which included information on demographic characteristics, diet, lifestyle, history of disease and medication use. Anthropometric measurements, including height and weight, were taken using standard operating procedures. Height and weight were measured to the nearest 0.1 cm and 0.1 kg, respectively, with the subject wearing light clothing and no shoes. BMI was calculated as weight (kg)/height (m2).

Current smoking was defined as having smoked ≥1 cigarette per day or ≥18 packs in the past year. Current alcohol drinking was defined as drinking alcohol at least two times per week in the past year. Diabetes was defined as having a history of diabetes or currently undergoing glucose-lowering therapy. Hyperlipidaemia was defined as having a history of hyperlipidaemia or currently undergoing lipid-lowering therapy. CVD was defined as having a history of stroke, coronary heart disease or heart failure. The question about standard of living was phrased as follows: ‘How is your standard of living?’ and a choice of three responses was given as follows: bad, medium and good. The question about fruit and green vegetable consumption was phrased as follows: ‘How much fruit and green vegetables do you eat (count the annually averaged weekly intake of fruits and green vegetables)?’ and a choice of three responses regarding weekly intake was given as follows: <500 g, 500–1500 g and ≥1500 g. The question about sleep quality was phrased as follows: ‘How do you describe your sleep quality?’ and a choice of three responses was given as follows: poor, medium and good. The question about sleep time was phrased as follows: ‘How long do you sleep every night?’ and a choice of three responses was given as follows: <5, 5–8 and ≥8 hours.

Trained research staff obtained systolic blood pressure (SBP) and DBP measurements after subjects had been seated for 10 min, using a validated automatic digital sphygmomanometer (Omron HEM 705IT device; Omron Healthcare), with appropriately sized cuffs. Triplicate measurements on the same arm were taken, with 1–2 min between readings. Each patient’s SBP and DBP were calculated as the mean of the three independent measures. Hypertension was defined as SBP ≥140 mm Hg and/or DBP ≥90 mm Hg.

Blood sample collection and laboratory methods

A fasting vein blood sample was obtained from each subject. Serum or plasma samples were separated within 30 min of collection and stored at −80°C. Serum tHcy levels were determined using commercial kits (Homocysteine Assay Kit (Hcy); Ausa Pharmed, Shenzhen, China) by enzymatic assay according to standard procedures.

Statistical analysis

Means (SD) and proportions were calculated for population characteristics by tHcy categories (<10, 10 to <15 and ≥15 μmol/L). Differences in population characteristics were compared using analysis of variance tests or χ2 tests, accordingly.

Hyperhomocysteinaemia has been defined as a tHcy concentration ≥10 µmol/L17 18 or 15 μmol/L19 in previous studies. Therefore, the clinical cut-off levels of tHcy were set at 10 and 15 µmol/L in our current study. Furthermore, to confirm the consistency of the results, multivariate linear regression models were performed to determine the associations between tHcy as a continuous variable, tHcy categories (<10 (reference), 10 to <15 and ≥15 μmol/L) based on the clinical definition or tHcy quartiles (Q1: <10.1 (reference), Q2: 10.1 to < 12.2, Q3: 12.2 to < 14.9 and Q4: ≥14.9 μmol/L) and SBP or DBP levels. Consistently, multivariate logistic regression models were performed to determine the associations between tHcy as a continuous variable, tHcy categories (<10 (reference), 10 to < 15 and ≥15 μmol/L), or tHcy quartiles (Q1: <10.1(reference), Q2: 10.1 to < 12.2, Q3: 12.2 to <14.9 and Q4: ≥14.9 μmol/L) and the prevalence of hypertension. All models were adjusted for age, sex, study communities, BMI, smoking and drinking status, living standard, fruit and vegetable consumption, sleep quality, history of diabetes, hyperlipidaemia and CVD. In the subgroup analyses, possible modifications of the association between tHcy and blood pressure were assessed for the variables, age (<60, ≥60), sex (male, female), BMI (<24, 24 to <28, ≥28 kg/m2), current smoking (yes, no), current alcohol drinking (yes, no), living standard (good, medium, bad), fruit and vegetable consumption (<500, 500 to < 1500, ≥1500 g), sleep quality (good, medium and poor) and sleep time (<5, 5 to <8 and ≥8 hours). Interactions were examined by including interaction terms in the multivariable linear regression models. BMI was categorised as normal weight (<24.0 kg/m2), overweight (24.0 to <28.0 kg/m2) and obesity (≥28.0 kg/m2) based on the guidelines of the Chinese Ministry of Health.20

A two-tailed p<0.05 was considered statistically significant in all analyses. All statistical analyses were performed by Empower(R) (www.empowerstats.com, X&Y Solutions, Boston, Massachusetts, USA) and statistical package R V.3.4.2 (http://www.r-project.org).

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 26 648 participants (9262 males and 17 386 females) with complete data on blood pressure and tHcy levels and with no antihypertensive drugs use were included in the final analysis. We speculated that the use of antihypertensive drugs may decrease the blood pressure and affect the association between tHcy and blood pressure levels. Therefore, these participants were excluded from the current analyses. A flow chart of the participants is shown in online supplementary figure 1.

bmjopen-2017-021103supp001.pdf (328.5KB, pdf)

The participants on average were 57.9 (SD: 10.3) years old with a mean tHcy levels of 13.2 (6.1) μmol/L. The participants were divided into three groups based on their baseline tHcy concentrations (<10, 10 to <15 and ≥15 μmol/L). General characteristics of these three groups are presented in table 1. The tHcy concentrations were directly associated with age, male sex, smoking and alcohol drinking and was inversely associated with BMI.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants by tHcy categories (n=26 648)

| Variables | tHcy, μmol/L | P values | ||

| <10 | 10 to <15 | ≥15 | ||

| N (%) | 6483 (24.3) | 13 689 (51.4) | 6476 (24.3) | |

| Age, year | 54.4±9.5 | 57.8±9.7 | 61.7±10.9 | <0.001 |

| Sex, male (%) | 1338 (20.6) | 4417 (32.3) | 3507 (54.2) | <0.001 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 24.9±3.8 | 24.9±3.6 | 24.7±3.7 | <0.001 |

| tHcy, μmol/L | 7.8±2.2 | 12.3±1.4 | 20.4±7.9 | <0.001 |

| Current smoking (%) | 597 (9.6) | 1919 (14.7) | 1482 (24.6) | <0.001 |

| Current alcohol drinking (%) | 719 (11.6) | 2208 (16.9) | 1513 (25.1) | <0.001 |

| Self-reported hyperlipidaemia | 370 (5.9) | 798 (6.1) | 378 (6.3) | 0.745 |

| Self-reported diabetes mellitus | 331 (5.3) | 631 (4.8) | 263 (4.4) | 0.050 |

| Self-reported cardiovascular diseases | 491 (7.9) | 1320 (10.1) | 867 (14.4) | <0.001 |

| SBP, mm Hg | 126.7±16.1 | 129.1±16.1 | 131.9±16.2 | <0.001 |

| DBP, mm Hg | 80.7±11.6 | 82.0±12.1 | 84.1±12.7 | <0.001 |

| Medication use, n (%) | ||||

| Lipid-lowering drugs | 38 (0.6) | 50 (0.4) | 30 (0.5) | 0.084 |

| Glucose-lowering drugs | 183 (2.8) | 365 (2.7) | 129 (2.0) | 0.004 |

| Living standards | <0.001 | |||

| Good | 734 (11.8) | 1850 (14.2) | 866 (14.4) | |

| Medium | 4835 (77.7) | 10 046 (77.0) | 4539 (75.4) | |

| Bad | 652 (10.5) | 1149 (8.8) | 613 (10.2) | |

| Fruit and vegetable consumption, g/week | <0.001 | |||

| <500 | 291 (4.7) | 498 (3.8) | 352 (5.8) | |

| 500–1500 | 1465 (23.5) | 3079 (23.6) | 1498 (24.9) | |

| ≥1500 | 4465 (71.8) | 9468 (72.6) | 4168 (69.3) | |

| Sleep quality | <0.001 | |||

| Good | 2784 (44.7) | 5821 (44.6) | 2906 (48.3) | |

| Medium | 2266 (36.4) | 4846 (37.1) | 2141 (35.6) | |

| Poor | 1172 (18.8) | 2396 (18.3) | 974 (16.2) | |

| Sleep time, hours | <0.001 | |||

| <5 | 476 (7.5) | 1177 (8.8) | 568 (9.1) | |

| 5–8 | 3843 (60.4) | 8123 (60.8) | 3591 (57.4) | |

| ≥8 | 2043 (32.1) | 4070 (30.4) | 2099 (33.5) | |

For continuous variables, values are presented as mean±SD.

DBP, diastolic blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure; tHcy, total homocysteine.

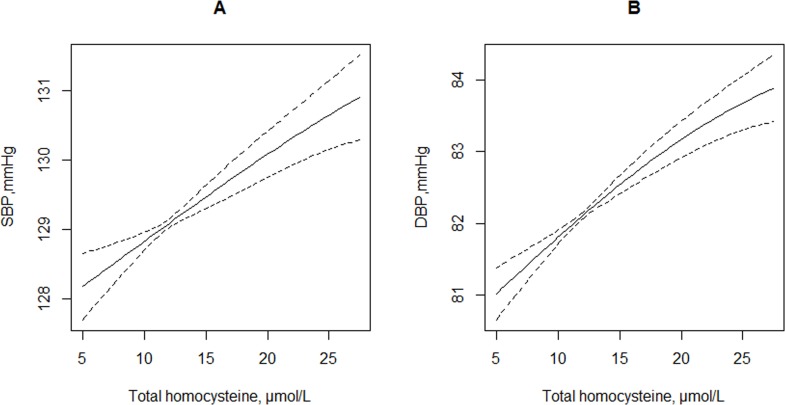

Association between tHcy concentrations and blood pressure

Overall, there was a positive association between tHcy concentrations and SBP or DBP levels (continuous variable). Each 5 μmol/L tHcy increment was associated with 0.45 mm Hg (95% CI 0.29 to 0.61 mm Hg) increase in SBP levels and 0.47 mm Hg (95% CI 0.35 to 0.59) increase in DBP levels (figure 1 and table 2). Compared with participants with tHcy <10 μmol/L, significantly higher SBP levels were found in those with tHcy 10–15 μmol/L (adjusted β=0.80 mm Hg; 95% CI 0.32 to 1.28) or ≥15 μmol/L (adjusted β=1.79 mm Hg; 95% CI 1.20 to 2.37; p for trend <0.001). Consistently, significantly higher DBP levels were found in participants with tHcy 10–15 μmol/L (adjusted β=0.86 mm Hg; 95% CI 0.49 to 1.22) or ≥15 μmol/L (adjusted β=2.01 mm Hg; 95% CI 1.57 to 2.46; p for trend <0.001) as compared with those with tHcy <10 μmol/L.

Figure 1.

The relationship of total homocysteine concentrations with SBP (A) and DBP (B) levels. Adjusted for age, sex, study communities, body mass index, smoking and drinking status, living standards, fruit and vegetable consumption, sleep quality, history of diabetes, hyperlipidaemia and cardiovascular disease. DBP, diastolic blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Table 2.

The relationship of total homocysteine with SBP and DBP levels, and the prevalence of hypertension

| Total Homocysteine, μmol/L | N | Mean±SD | Unadjusted | Adjusted* | ||

| β (95% CI) | P values | β (95% CI) | P values | |||

| SBP, mm Hg | ||||||

| Per 5 μmol/L increase | 26 648 | 129.2±16.3 | 1.16 (1.00 to 1.32) | <0.001 | 0.45 (0.29 to 0.61) | <0.001 |

| Categories | ||||||

| <10 | 6483 | 126.7±16.1 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| 10 to <15 | 13 689 | 129.1±16.1 | 2.43 (1.95 to 2.90) | <0.001 | 0.80 (0.32 to 1.28) | 0.001 |

| ≥15 | 6476 | 131.9±16.2 | 5.26 (4.71 to 5.82) | <0.001 | 1.79 (1.20 to 2.37) | <0.001 |

| P for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| DBP, mm Hg | ||||||

| Per 5 μmol/L increase | 26 648 | 82.2±12.2 | 0.86 (0.74 to 0.98) | <0.001 | 0.47 (0.35 to 0.59) | <0.001 |

| Categories | ||||||

| <10 | 6483 | 80.7±11.6 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| 10 to <15 | 13 689 | 82.0±12.1 | 1.37 (1.01 to 1.73) | <0.001 | 0.86 (0.49 to 1.22) | <0.001 |

| ≥15 | 6476 | 84.1±12.7 | 3.44 (3.02 to 3.86) | <0.001 | 2.01 (1.57 to 2.46) | <0.001 |

| P for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Hypertension† | N | Events (%) | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||

| OR (95% CI) | P values | OR (95% CI) | P values | |||

| Per 5 μmol/L increase | 26 648 | 8536 (32.0) | 1.14 (1.12 to 1.17) | <0.001 | 1.07 (1.04 to 1.09) | <0.001 |

| Categories | ||||||

| <10 | 6483 | 1700 (26.2) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| 10 to <15 | 13 689 | 4296 (31.4) | 1.29 (1.20 to 1.37) | <0.001 | 1.12 (1.04 to 1.21) | 0.003 |

| ≥15 | 6476 | 2540 (39.2) | 1.82 (1.69 to 1.96) | <0.001 | 1.32 (1.21 to 1.44) | <0.001 |

| P for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

*Adjusted for age, sex, study communities, body mass index, smoking and drinking status, living standards, fruit and vegetable consumption, sleep quality, history of diabetes, hyperlipidaemia and cardiovascular disease.

†Hypertension was defined as SBP ≥140 mm Hg and/or DBP ≥90 mm Hg.

DBP, diastolic blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

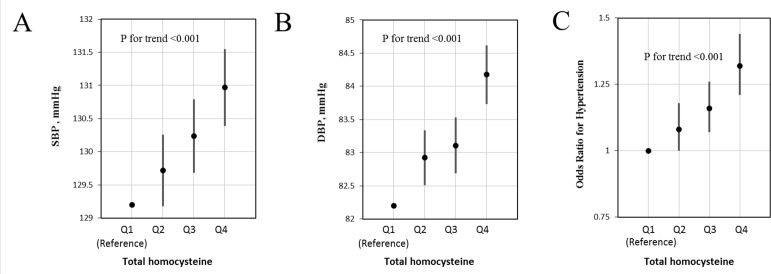

Accordingly, the prevalence of hypertension (binary variables) increased with the increment tHcy (per 5 μmol/L increment: OR 1.07; 95% CI 1.04 to 1.09) (online supplementary figure 2 and table 2). The prevalence of hypertension was higher in subjects with higher tHcy concentrations: 26.2% in the tHcy <10 μmol/L group, 31.4% in the tHcy 10–15 μmol/L group and 39.2% in the tHcy ≥15 μmol/L group. Compared with those with tHcy <10 μmol/L, the adjusted ORs were 1.12 (95% CI 1.04 to 1.21) and 1.32 (95% CI 1.21 to 1.44) for the tHcy 10–15 μmol/L group and the tHcy ≥15 µmol/L group, respectively (p for trend <0.001, table 2).

Similarly, SBP and DBP levels and the prevalence of hypertension increased through the quartiles of tHcy concentrations as did the adjusted ORs (All p for trend <0.001) (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Systolic blood pressure (SBP) levels (A), diastolic blood pressure (DBP) levels (B) and the adjusted ORs of hypertension (C) by quartiles* of total homocysteine (tHcy) concentrations†. *tHcy quartiles: Q1:<10.1 (reference group), Q2:10.1 to <12.2, Q3: 12.2 to <14.9 and Q4: ≥14.9 μmol/L. †Adjusted for age, sex, study communities, body mass index, smoking and drinking status, living standards, fruit and vegetable consumption, sleep quality, history of diabetes, hyperlipidaemia and cardiovascular disease.

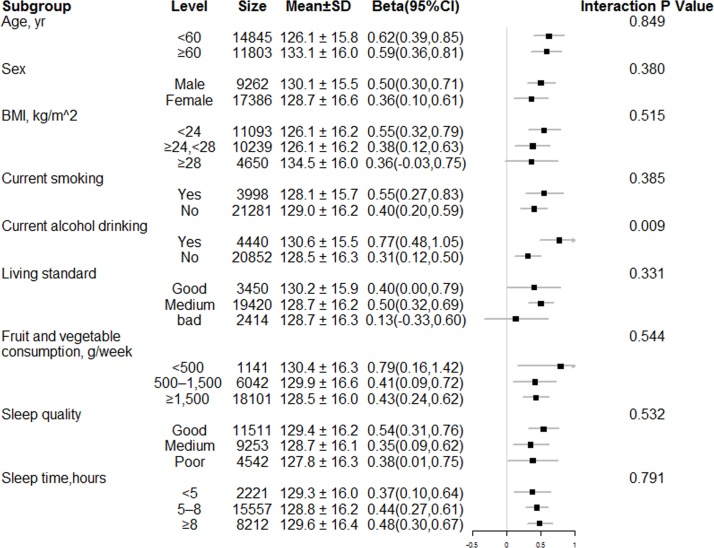

Stratified analyses by potential effect modifiers

Stratified analyses were performed to assess the association between tHcy and SBP (figure 3) and DBP (online supplementary figure 3) levels in various subgroups. Alcohol drinking positively modified the association between tHcy and SBP (p for interaction=0.009) and DBP (p for interaction=0.067) levels. A stronger association between tHcy and SBP or DBP levels was found in current alcohol drinkers. Other variables, including age, sex, BMI, smoking, living standards, fruit and vegetable consumption, sleep quality and sleep time, did not significantly modify the relationship of tHcy with SBP or DBP levels.

Figure 3.

Stratified analyses by potential effect modifiers for the association between total homocysteine and systolic blood pressure levels. Adjusted for age, sex, study communities, body mass index (BMI), smoking and drinking status, living standards, fruit and vegetable consumption, sleep quality, history of diabetes, hyperlipidaemia and cardiovascular disease.

Discussion

Typically, Chinese populations are characterised by elevated tHcy, a high prevalence of the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) C677T mutation, and no dietary folic acid fortification, rendering the current study population best suitable for examining the association between tHcy and blood pressure levels.21–23 Our study included a total of 26 648 male and female adults with no antihypertensive drugs usage, by far the largest study of its kind. Our study has provided some new insights. First, there was a significantly linear association between tHcy and SBP or DBP levels in the general population. Second, alcohol drinking was an important modifier for the association between tHcy and SBP or DBP levels.

MTHFR is the main regulatory enzyme for folate/homocysteine metabolism. Polymorphism of MTHFR 677C>T leads to a reduction in enzyme activity, resulting in increased concentrations of plasma Hcy and lower levels of serum folate. MTHFR C677T polymorphism has been reported to be associated with hypertension or high blood pressure. In line with our results, the studies by Heifetz and Birk had shown that tHcy may contribute to the effect of MTHFR C677T genotypes on blood pressure levels.24 More importantly, Saraswathy et al 25 also suggested that MTHFR 677TT genotype and elevated tHcy levels (even in the upper limits of the normal range of 5–15 μmol/L) are significantly associated with hypertension regardless of age and gender in a Northeastern population with East Asian ancestry.

There are several potential mechanisms by which increased tHcy could contribute to high blood pressure. Raised tHcy has been shown to be associated with increased oxidative stress, hypertrophy of vascular muscle and changes in DNA methylation.26–28 Furthermore, tHcy may induce endothelial dysfunction via increased asymmetric dimethylarginine, increased inflammation and decreased bioavailability of endothelium-derived NO.27 Higher tHcy could also activate metalloproteinase and induces collagen synthesis and causes imbalances of elastin/collagen ratio. More importantly, elevated tHcy promoted ACE activity that may lead to upregulation of angiotensin II and subsequently hypertension.29

Our data also showed that a stronger association between tHcy and SBP or DBP levels was found in current alcohol drinkers. There are several possible explanations. First, it has been reported that acetaldehyde, a production of ethanol metabolite, could inhibit homocysteine remethylation by affecting the methionine synthase.30 Furthermore, previous studies have also suggested that alcohol consumption may lead to folate deficiency due to the malabsorption, and increased urinary excretion.31 Additionally, alcohol drinkers usually had a significantly higher frequency of MTHFR C677T mutation.32 Therefore, alcohol drinkers may experience more severe tHcy-related vascular damage, which could partly explain the stronger association between tHcy and blood pressure levels in the current alcohol drinkers seen in this study. However, the exact mechanisms regarding the relationship of tHcy and alcohol drinking with the blood pressure levels remain to be further investigated, and our findings also warrant further confirmation.

It has been reported that higher folate intake is associated with a lower incidence of hypertension as seen in both the Nurses’ Health Study33 and the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults study.34 Williams et al,35 van Dijk et al 36 and a recent meta-analysis12 of relevant randomised trials among patients with hypertension and hyperhomocysteinaemia reported that tHcy lowering with folic acid therapy may reduce the blood pressure levels. Our previous study37 also suggested that elevated tHcy concentration significantly decreased the antihypertensive effect of both short-term and long-term enalapril-based antihypertensive treatment. However, studies by Moens et al,38 Doshi et al 39 and the CSPPT study13 found no obvious effect between folic acid therapy and blood pressure levels. We speculate that the folic acid fortification of enriched cereal grain in North American countries effective since January 1998, and the concomitant use of antihypertensive drugs may possibly have modified the treatment effect in previous studies. Therefore, the power for detecting the beneficial effect of folic acid therapy on blood pressure may be limited in previous studies. A large-scale clinical trial is needed to further investigate and confirm the effect of tHcy lowering on blood pressure levels with and without the concomitant use of antihypertensive drugs.

Several potential concerns or limitations are worth mentioning. First, as a cross-sectional study, we were not able to determine the causal relationship between tHcy and blood pressure levels. Second, the participants in our current study were recruited from the community through open recruitment rather than a random sampling strategy, which may have affected the representativeness of the population. The generalisability of our findings to other populations remains to be explored. Third, we did not measure the tHcy-related genetic variants, and could not evaluate the possible role of these variants in our current study. Fourth, although diabetes and dyslipidaemia had been included in the analyses, we did not have the actual values for blood glucose and lipids. Fifth, some of the information in our study was taken by questionnaire and this information could be biased. However, these questionnaires had been validated, and been applied to numerous previous projects.2 40 41 In addition, we did not follow the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders criteria for the categorisation of alcoholics. Due to these limitations, confirmation of our findings in an independent study is essential.

Conclusions

Serum tHcy concentrations were positively associated with both SBP and DBP levels in a general Chinese adult population. The association was stronger in current alcohol drinkers. Our findings raise the possibility that a better understanding of the mechanism by which elevated Hcy effects blood pressure levels, may help to improve hypertension prevention and control, a burgeoning concern in clinical and community settings.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

HW and BW contributed equally.

XQ and XX contributed equally.

Contributors: Study concept and design: XX, HW, BW, QB, LC, DY, YY, YS, CL, JC, JZ, YZ, TZ, HZ, HG, GT, YZ, JL, YH, TZ and XQ. Conduct of study: HW, BW, YY, QB, LC, YS, JC, JZ, YZ, JL, GT, YZ, TZ, YH, TZ and XQ. Data management and statistical analysis: HW, BW, CL and XQ. Drafting of the manuscript: HW, BW and XQ. Critical review and revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: XX, HW, BW, QB, LC, DY, YY, YS, CL, JC, JZ, YZ, TZ, HZ, HG, GT, YZ, JL, YH, TZ and XQ.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Key Research andDevelopment Program [2016YFC0903103, 2016YFC0904900, 2016YFE0205400, 2018ZX09739,2018ZX09301034003], the Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangzhou, China [201707020010]; and the Science, Technology and Innovation Committee ofShenzhen [KQCX20120816105958775, JSGG20170412155639040, GJHS20170314114526143, KC2014JSCX0071A]; President Foundation of Nanfang Hospital, Southern MedicalUniversity (2017C007); Outstanding Youths Development Scheme of NanfangHospital, Southern Medical University (2017J009).

Competing interests: XX reports grants from the Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangzhou, China (201707020010) and the Science, Technology and Innovation Committee of Shenzhen (KQCX20120816105958775, JSGG20170412155639040, GJHS20170314114526143, KC2014JSCX0071A). XQ reports grants from the President Foundation (2017C007) and Outstanding Youths Development Scheme of Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University (2017J009). BW reports grants from the National Key Research and Development Program (2016YFC0903103, 2016YFC0904900, 2016YFE0205400, 2018ZX09739, 2018ZX09301034003). No other disclosures were reported.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Biomedicine, Anhui Medical University (Hefei, China).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data, analytical methods and study materials that support the findings of this study will be available from the corresponding author (XX) on request, after the request is submitted and formally reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Biomedicine, Anhui Medical University.

References

- 1. Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, et al. Task Force Members. 2013 ESH/ESC Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). J Hypertens 2013;31:1281–357. 10.1097/01.hjh.0000431740.32696.cc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. He M, Qin X, Cui Y, et al. Prevalence of unrecognized lower extremity peripheral arterial disease and the associated factors in chinese hypertensive adults. Am J Cardiol 2012;110:1692–8. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.07.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, et al. Global burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide data. Lancet 2005;365:217–23. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)70151-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Xie D, Yuan Y, Guo J, et al. Hyperhomocysteinemia predicts renal function decline: a prospective study in hypertensive adults. Sci Rep 2015;5:16268 10.1038/srep16268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cybulska B, Kłosiewicz-Latoszek L. Homocysteine–is it still an important risk factor for cardiovascular disease? Kardiol Pol 2015;73:1092–6. 10.5603/KP.2015.0229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Li J, Jiang S, Zhang Y, et al. H-type hypertension and risk of stroke in chinese adults: A prospective, nested case-control study. J Transl Int Med 2015. 3:171–8. 10.1515/jtim-2015-0027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ganguly P, Alam SF. Role of homocysteine in the development of cardiovascular disease. Nutr J 2015;14:6 10.1186/1475-2891-14-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Refsum H, Nurk E, Smith AD, et al. The Hordaland Homocysteine Study: a community-based study of homocysteine, its determinants, and associations with disease. J Nutr 2006;136(6 Suppl):1731S–40. 10.1093/jn/136.6.1731S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lim U, Cassano PA. Homocysteine and blood pressure in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. Am J Epidemiol 2002;156:1105–13. 10.1093/aje/kwf157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Li WX, Liao P, Hu CY, et al. Interactions of Methylenetetrahydrofolate Reductase Gene Polymorphisms, Folate, and Homocysteine on Blood Pressure in a Chinese Hypertensive Population. Clin Lab 2017;63:817–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li Z, Guo X, Chen S, et al. Hyperhomocysteinemia independently associated with the risk of hypertension: a cross-sectional study from rural China. J Hum Hypertens 2016;30:508–12. 10.1038/jhh.2015.75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang WW, Wang XS, Zhang ZR, et al. A Meta-Analysis of Folic Acid in Combination with Anti-Hypertension Drugs in Patients with Hypertension and Hyperhomocysteinemia. Front Pharmacol 2017;8:585 10.3389/fphar.2017.00585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Huo Y, Li J, Qin X, et al. Efficacy of folic acid therapy in primary prevention of stroke among adults with hypertension in China: the CSPPT randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2015;313:1325–35. 10.1001/jama.2015.2274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fakhrzadeh H, Ghotbi S, Pourebrahim R, et al. Plasma homocysteine concentration and blood pressure in healthy Iranian adults: the Tehran Homocysteine Survey (2003-2004). J Hum Hypertens 2005;19:869–76. 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dinavahi R, Cossrow N, Kushner H, et al. Plasma homocysteine concentration and blood pressure in young adult African Americans. Am J Hypertens 2003;16(9 Pt 1):767–70. 10.1016/S0895-7061(03)00986-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sundström J, Sullivan L, D’Agostino RB, et al. Plasma homocysteine, hypertension incidence, and blood pressure tracking: the Framingham Heart Study. Hypertension 2003;42:1100–5. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000101690.58391.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stanger O, Herrmann W, Pietrzik K, et al. DACH-LIGA homocystein (german, austrian and swiss homocysteine society): consensus paper on the rational clinical use of homocysteine, folic acid and B-vitamins in cardiovascular and thrombotic diseases: guidelines and recommendations. Clin Chem Lab Med 2003;41:1392–403. 10.1515/CCLM.2003.214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Malinow MR, Bostom AG, Krauss RM. Homocyst(e)ine, diet, and cardiovascular diseases: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Nutrition Committee, American Heart Association. Circulation 1999;99:178–82. 10.1161/01.CIR.99.1.178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Eikelboom JW, Lonn E, Genest J, et al. Homocyst(e)ine and cardiovascular disease: a critical review of the epidemiologic evidence. Ann Intern Med 1999;131:363–75. 10.7326/0003-4819-131-5-199909070-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chen C, Lu FC. Department of Disease Control Ministry of Health, PR China. The guidelines for prevention and control of overweight and obesity in Chinese adults. Biomed Environ Sci 2004;17 Suppl:1–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Qin X, Li J, Cui Y, et al. Effect of folic acid intervention on the change of serum folate level in hypertensive Chinese adults: do methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase and methionine synthase gene polymorphisms affect therapeutic responses? Pharmacogenet Genomics 2012;22:421–8. 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32834ac5e8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Qin X, Li J, Cui Y, et al. MTHFR C677T and MTR A2756G polymorphisms and the homocysteine lowering efficacy of different doses of folic acid in hypertensive Chinese adults. Nutr J 2012;11:2 10.1186/1475-2891-11-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wilcken B, Bamforth F, Li Z, et al. Geographical and ethnic variation of the 677C>T allele of 5,10 methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR): findings from over 7000 newborns from 16 areas world wide. J Med Genet 2003;40:619–25. 10.1136/jmg.40.8.619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Heifetz EM, Birk RZ. MTHFR C677T polymorphism affects normotensive diastolic blood pressure independently of blood lipids. Am J Hypertens 2015;28:387–92. 10.1093/ajh/hpu152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Saraswathy KN, Garg PR, Salam K, et al. MTHFR C677T polymorphism and its homocysteine-driven effect on blood pressure. Int J Stroke 2014;9:E20 10.1111/ijs.12276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Briones AM, Touyz RM. Oxidative stress and hypertension: current concepts. Curr Hypertens Rep 2010;12:135–42. 10.1007/s11906-010-0100-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pushpakumar S, Kundu S, Sen U. Endothelial dysfunction: the link between homocysteine and hydrogen sulfide. Curr Med Chem 2014;21:3662–72. 10.2174/0929867321666140706142335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Topal G, Brunet A, Millanvoye E, et al. Homocysteine induces oxidative stress by uncoupling of NO synthase activity through reduction of tetrahydrobiopterin. Free Radic Biol Med 2004;36:1532–41. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sen U, Mishra PK, Tyagi N, et al. Homocysteine to hydrogen sulfide or hypertension. Cell Biochem Biophys 2010;57(2-3):49–58. 10.1007/s12013-010-9079-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stickel F, Choi SW, Kim YI, et al. Effect of chronic alcohol consumption on total plasma homocysteine level in rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2000;24:259–64. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2000.tb04606.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bleich S, Carl M, Bayerlein K, et al. Evidence of increased homocysteine levels in alcoholism: the Franconian alcoholism research studies (FARS). Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2005;29:334–6. 10.1097/01.ALC.0000156083.91214.59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Benyamina A, Saffroy R, Blecha L, et al. Association between MTHFR 677C-T polymorphism and alcohol dependence according to Lesch and Babor typology. Addict Biol 2009;14:503–5. 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2009.00169.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Forman JP, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, et al. Folate intake and the risk of incident hypertension among US women. JAMA 2005;293:320–9. 10.1001/jama.293.3.320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Xun P, Liu K, Loria CM, et al. Folate intake and incidence of hypertension among American young adults: a 20-y follow-up study. Am J Clin Nutr 2012;95:1023–30. 10.3945/ajcn.111.027250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Williams C, Kingwell BA, Burke K, et al. Folic acid supplementation for 3 wk reduces pulse pressure and large artery stiffness independent of MTHFR genotype. Am J Clin Nutr 2005;82:26–31. 10.1093/ajcn/82.1.26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. van Dijk RA, Rauwerda JA, Steyn M, et al. Long-term homocysteine-lowering treatment with folic acid plus pyridoxine is associated with decreased blood pressure but not with improved brachial artery endothelium-dependent vasodilation or carotid artery stiffness: a 2-year, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2001;21:2072–9. 10.1161/hq1201.100223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Qin X, Li Y, Sun N, et al. Elevated Homocysteine Concentrations Decrease the Antihypertensive Effect of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors in Hypertensive Patients. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2017;37:166–72. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.308515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Moens AL, Claeys MJ, Wuyts FL, et al. Effect of folic acid on endothelial function following acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2007;99:476–81. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.08.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Doshi SN, McDowell IF, Moat SJ, et al. Folic acid improves endothelial function in coronary artery disease via mechanisms largely independent of homocysteine lowering. Circulation 2002;105:22–6. 10.1161/hc0102.101388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Qin X, Zhang Y, Cai Y, et al. Prevalence of obesity, abdominal obesity and associated factors in hypertensive adults aged 45-75 years. Clin Nutr 2013;32:361–7. 10.1016/j.clnu.2012.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Qin X, Li J, Zhang Y, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of diabetes and impaired fasting glucose in Chinese hypertensive adults aged 45 to 75 years. PLoS One 2012;7:e42538 10.1371/journal.pone.0042538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-021103supp001.pdf (328.5KB, pdf)