Abstract

Objective

To examine the prevalence of sexual assaults among individuals with visual impairment (VI) compared with the general population and to investigate the association between sexual assault and outcomes of self-efficacy and life satisfaction.

Design

Cross-sectional interview-based study conducted between February and May 2017.

Participants

A probability sample of adults with VI (≥18 years) who were members of the Norwegian Association of the Blind and Partially Sighted. A total of 736 (61%) members participated, of whom 55% were of female gender. We obtained norm data for sexual assaults from a representative survey of the general Norwegian population.

Outcome measures

Sexual assaults (Life Event Checklist for DSM-5), self-efficacy (General Self-Efficacy Scale) and life satisfaction (Cantril’s Ladder of Life Satisfaction).

Results

The prevalence of sexual assaults (rape, attempted rape and forced into sexual acts) in the VI population was 17.4% (95% CI 14.0 to 21.4) among women and 2.4% (95% CI 1.2 to 4.7) among men. For women, the VI population had higher rates of sexual assaults across age strata than the general population. For men, no significant differences were found. In the population of people with VI, the risk of sexual assault was greater for those having other impairments in addition to the vision loss. Individuals with VI who experienced sexual assaults had lower levels of self-efficacy (adjusted relative risk (ARR): 0.18, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.61) and life satisfaction (ARR: 0.31, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.50) than others.

Conclusions

The risk of experiencing sexual assault appears to be higher in individuals with VI than in the general population. Preventive measures as well as psychosocial care for those who have been exposed are needed.

Keywords: rape and sexual assault, visual impairment, blindness, self-efficacy, life satisfaction

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A large probability sample of people with visual impairments made it possible to address the prevalence of sexual assaults within age groups.

Use of interview-based assessments with validated instruments and detailed information about characteristics of visual impairment.

The representativeness of the study sample is questionable as participants were recruited from a membership organisation of blind and partially sighted.

The findings should be interpreted in light of the possible impact of bias due to non-participation, recall and self-disclosure.

Introduction

Sexual assault, which in this study refers to forms of violence such as rape and forced sexual acts, is shown to be a strong determinant of people’s health and well-being.1–3 Sexual transmittable infections and unwanted pregnancies are common among those who have been sexually assaulted,4 and about half of the reported cases involve physical injury.5 Sexual assault is largely about power and oppression and is being viewed today as a social problem with structural and cultural roots.6 So far, sexual assault research has focused primarily on women,7 while less is known about marginalised groups such as men having sex with men8 and people with specific impairments.9 10

Visual impairment (VI) is defined as functional restrictions of the visual system.11 According to the WHO categorisation system,12 a diagnosis of VI is set through direct assessments of visual acuity and visual field and classified into moderate to severe VI, blindness and undetermined VI. VI is a heterogeneous condition occurring at any point in life and has a diverse set of causes, severities and progression rates.13 14 Furthermore, the majority of people with VI have other impairments in addition to their vision loss, being closely connected to conditions such as cerebral paresis, multiple sclerosis, diabetes and hearing impairment.15–17

A few observational studies from Europe and the USA have been published on the prevalence of sexual assault in people with low vision or blindness.18–22 In the previous studies, the reported lifetime prevalence of sexual assault or abuse has varied, with estimates ranging between 11% and 30%.18 19 21 22 The varying estimates may be attributed to a number of methodological factors, but it could also be related to the inclusion of samples with different types and degrees of vision loss. However, limited evidence exists on the extent of sexual assault across subgroups of people with various VI characteristics,18 and more research is therefore needed.

Given the uncertainty about the prevalence of sexual assaults in people with VI and its possible associations with various VI characteristics, we conducted a cross-sectional study by including a probability sample of adults with VI. The study had the following three main aims: (1) to estimate the prevalence of sexual assaults compared with the general population, (2) to examine the association of sexual assaults with VI-related characteristics and (3) to examine the association between sexual assaults and outcomes of self-efficacy and life satisfaction.

Methods

VI population

This cross-sectional study comprised adult members (≥18 years) of the Norwegian Association of the Blind and Partially Sighted who had a diagnosis of VI. The organisation has about 10 000 members,23 encompassing 0.2% of the Norwegian population. To ensure adequate number of participants in the younger age groups, simple random sampling was performed within each of the following four age strata: 18–35, 36–50, 51–65 and ≥66. Data were collected through structured telephone interviews in the time period between 1 February and 31 May 2017 by a private survey company. A total of 1216 adults were contacted, and 736 (61%) participated by completing the interview. The online supplement includes a flow chart of the sample selection (online supplementary figure 1) and a detailed description of characteristics within each degree of VI (online supplementary table S1).

bmjopen-2018-021602supp001.pdf (163.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-021602supp002.pdf (83.6KB, pdf)

General population

Norm data were based on the Norwegian Population Study, a cross-sectional survey including a representative sample of adults (≥18 years) from the general Norwegian population.24 Simple random sampling was conducted based on names and addresses from the Central National Register of Norway, and efforts were made to ensure that the sample reflected the Norwegian population in terms of age, gender and geographical location. The study data were collected by postal questionnaires in the period between 2014 and 2015. Of the 5500 eligible participants, 9 persons had died, 21 were not able to fill out the questionnaire and 499 envelopes had non-valid addresses. This resulted in a total of 4971 individuals, and 1792 (36%) of those participated by completing and returning the postal questionnaire.

Measurements

Covariates

In both surveys, sociodemographic data included age (years: 18–35, 36–50, 51–65 and ≥66), gender, urbanicity (inhabitants: <20 000 and ≥20 000), current education level (years: <11, 11–13 and ≥14), work status (unemployed, employed/under education and retired) and marital status (single, married/partner, divorced and widowed).

Participants with VI were asked to report their corrected degree of VI in the better-seeing eye (blind, severe VI, moderate VI and undetermined), progression rate of vision loss (stable and progressive) and total years lived with VI. An ‘age of VI onset’ variable was created by substracting the participants’ age by their reporting on years lived with VI. The variable was then categorised into: ‘since birth (0 years)’, ‘childhood/youth (1–24 years)’ and ‘adulthood (≥25 years)’. Furthermore, the participants were asked to describe whether they had other impairments in addition to their VI. The response alternatives were: ‘no’, ‘yes, to some extent’ and ‘yes, to a great extent’. Participants who reported impairment to some or great extent were included in the ‘yes’ category, while those who reported having no other impairments were included in the ‘no’ category.

Sexual assaults

In both surveys, past experience of sexual assaults was measured by the Life Event Checklist for DSM-5. The questionnaire has demonstrated adequate test–retest reliability and moderate correlation with trauma-related mental disorders.25 In the list of life events, participants were asked to describe whether they had experienced sexual assaults (rape, attempted rape, made to perform any type of sexual act through force or threat of harm). Those who reported ‘that happened me’ were categorised as ‘yes’ (1) and those who reported otherwise were categorised as ‘no’ (0).

Self-efficacy

The General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSE scale) was included to assess perception of self-efficacy in the VI population. The Norwegian version of the GSE scale has been shown to have a high test–retest reliability (r=0.82) and acceptable correlations with life satisfaction (r=0.26) and positive affect (r=0.40).26 The scale consists of 10 statements about the participant’s belief in one’s ability to adequately respond to novel or challenging situations and to cope with a variety of stressors and is scored on a 4-point Likert scale from 1 (not at all true) to 4 (exactly true). A sum score was calculated based on all 10 items, with higher scores representing greater self-efficacy. The sum score was treated as an untransformed continuous variable in our main analyses. The GSE scale had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89.

Life satisfaction

Cantril’s Ladder of Life Satisfaction was used to measure current life satisfaction in the VI population.27 The participants were asked to imagine themselves a ladder with 10 steps, of which the bottom of the ladder represented the worst possible life for them (a score of 0), and the top of the ladder represented the best possible life for them (a score of 10). The scale was treated as an untransformed continuous variable in the regression analyses.

Statistical methods

We assessed the lifetime prevalence of sexual assaults in the VI population and in the general population within strata of age and gender. All stratified proportions were estimated with corresponding 95% exact binomial CIs. Test of statistical significance was performed using Fisher’s exact test.

We used generalised linear models (GLMs) with binomial distribution and log-link function to estimate relative risks (RRs) and 95% CIs of sexual assaults in its association with each VI-specific factor (VI severity, age of VI onset, VI stability and having other impairments). Model fit was evaluated using residual plots. The models were either unadjusted or age adjusted and gender adjusted. No risk ratio modifications were observed of age or gender with each of the VI-specific factors (p>0.05).

GLM with Gaussian distribution and identity-link function was used to estimate mean scores of self-efficacy and life satisfaction of those who had experienced sexual assaults, compared with the reference of no sexual assaults. Model estimates were presented in terms of RRs and 95% CIs. Model fit was evaluated using residual plots. The GLMs were either unadjusted or adjusted for age (years: 18–35, 36–50, 51–65 and ≥66), gender, education (years: <11, 11–13 and ≥14) and VI severity (moderate VI, severe VI, blindness and undetermined VI). No risk ratio modifications were found of sexual assault with each of the possible confounding factors (p>0.05).

The significance level was set at p=0.05. The statistical analyses were carried out using Stata V.14.

Patient and public involvement

The study was planned by an expert group, consisting of researchers on disability, rehabilitation personnel and board members from the Norwegian Association of the Blind and Partially Sighted. Most participants had personal experiences as they themselves were visually impaired or blind. Dissemination of findings to members of the Norwegian Association of the Blind and Partially Sighted will be arranged via different channels. The work will be published in open-access peer-reviewed journals so that all members have opportunity to read the articles. Furthermore, we will have a direct communication with the organisation to provide results of key relevance to the organisation and holding presentations to members on request. We will also work together with the organisation to reach media through press releases and to reach stakeholders through policy briefs.

Ethics

All participants gave their informed consent for taking part in the study. Study participation was voluntary, and the participants were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time.

Results

Table 1 shows the study characteristics of the VI population and the general population. The age distribution of the VI population (mean: 51.4, range: 18–95) was similar to that of the general population (mean: 53.2, range: 18–94). In both surveys, non-participants were more likely than participants to be of young or old age.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the visual impairment population (VI) and the general population (GP), according to gender

| Characteristics | Female VI | Female GP | Male VI | Male GP |

| (n=403) | (n=941) | (n=333) | (n=828) | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18–35 | 88 (21.8) | 189 (20.1) | 69 (20.7) | 105 (12.7) |

| 36–50 | 101 (25.1) | 273 (28.9) | 85 (25.5) | 184 (22.2) |

| 51–65 | 106 (26.3) | 267 (28.4) | 94 (28.2) | 286 (34.5) |

| ≥66 | 108 (26.8) | 212 (22.5) | 85 (25.5) | 253 (30.6) |

| Urbanicity | ||||

| <20 000 inhabitants | 227 (56.3) | 444 (47.3) | 172 (51.7) | 399 (48.9) |

| ≥20 000 inhabitants | 176 (43.7) | 494 (52.7) | 161 (48.4) | 426 (51.1) |

| Education (years) | ||||

| <11 | 69 (17.1) | 79 (8.4) | 46 (13.8) | 62 (7.5) |

| 11–13 | 162 (40.2) | 346 (36.7) | 124 (37.2) | 336 (40.5) |

| ≥14 | 172 (42.7) | 517 (54.9) | 163 (49.0) | 432 (52.0) |

| Work status | ||||

| Employed/studying | 154 (38.2) | 641 (68.3) | 160 (48.1) | 526 (63.1) |

| Unemployed | 152 (37.7) | 82 (8.7) | 73 (21.9) | 60 (7.2) |

| Retired | 97 (24.1) | 216 (23.0) | 100 (30.0) | 224 (29.3) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 131 (32.5) | 133 (14.2) | 129 (38.7) | 96 (11.6) |

| Married/partnership | 181 (44.9) | 698 (74.3) | 166 (49.9) | 672 (80.9) |

| Divorced | 46 (11.4) | 59 (6.2) | 25 (7.5) | 38 (4.6) |

| Widowed | 45 (11.2) | 49 (5.2) | 13 (3.9) | 25 (3.0) |

A total of 78 (10.6%, 95% CI 8.5 to 13.1) of adults with VI and 109 (6.1%, 95% CI 5.1 to 7.3) of adults from the general population reported having at some time experienced sexual assaults. Table 2 displays the prevalence rates of sexual assaults across strata of age and gender. For women, a higher prevalence of sexual assaults was observed among individuals with VI than that of the general population, and the largest difference was found among those aged 36–50 years. For men, no significant differences were observed. The female/male ratio was 7.3 for the VI population and 5.9 for the general population.

Table 2.

Prevalence of sexual assaults in the visual impairment population (VI) and in the general population (GP), according to age and gender

| Female VI (n=403)* | Female GP (n=941)* | P values† | Male VI (n=333)* | Male GP (n=828)† | P values† | |||||

| Cases/tot | % (95% CI) | Cases/tot | % (95% CI) | Cases/tot | % (95% CI) | Cases/tot | % (95% CI) | |||

| Age groups (years) | ||||||||||

| 18–35 | 15/88 | 17.1 (10.5 to 26.5) | 22/189 | 11.6 (7.8 to 17.1) | 0.26 | 1/69 | 1.5 (0.2 to 9.7) | 1/105 | 1.0 (0.1 to 6.5) | 1.00 |

| 36–50 | 26/101 | 25.7 (18.1 to 35.2) | 31/273 | 11.4 (8.1 to 15.7) | 0.001 | 4/85 | 4.7 (1.8 to 12.0) | 3/184 | 1.6 (0.5 to 5.0) | 0.21 |

| 51–65 | 17/106 | 16.0 (10.2 to 24.4) | 28/267 | 10.5 (7.3 to 14.8) | 0.16 | 2/94 | 2.1 (0.5 to 8.2) | 6/286 | 2.1 (0.9 to 4.6) | 1.00 |

| ≥66 | 12/108 | 11.1 (6.4 to 18.6) | 13/212 | 6.1 (3.6 to 10.3) | 0.13 | 1/85 | 1.2 (0.2 to 8.0) | 4/253 | 1.6 (0.6 to 4.1) | 1.00 |

| Total | 70/403 | 17.4 (14.0 to 21.4) | 94/941 | 10.0 (8.3 to 12.1) | <0.001 | 8/333 | 2.4 (1.2 to 4.7) | 14/828 | 1.7 (1.0 to 2.8) | 0.48 |

*No missing data due to non-response for the VI population, while there were 23 participants from the general population who did not respond to questions related to age and/or gender.

†P value calculated using Fisher’s exact test.

tot, total number of participants in that particular subgroup.

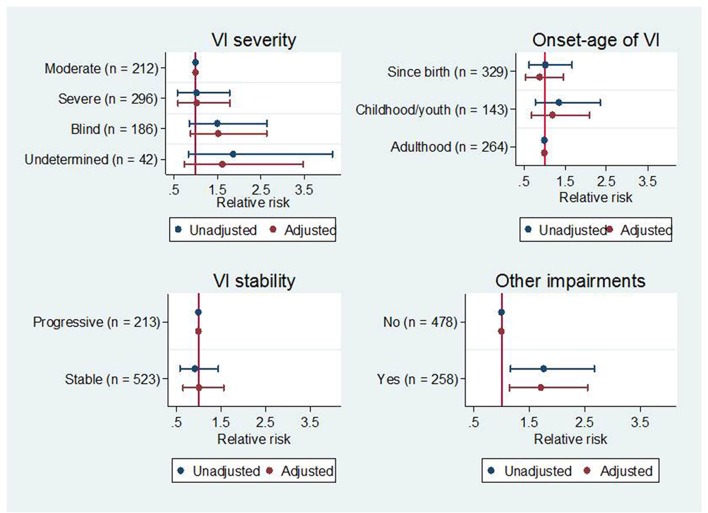

Figure 1 displays the unadjusted and age-adjusted and gender-adjusted risk of sexual assaults for VI-related characteristics in the VI population. Individuals with other impairments in addition to their vision loss had a greater risk of experiencing sexual assaults (RR: 1.71, 95% CI 1.15 to 2.55) than individuals who did not have any other impairments. No significant associations were found with other VI-related factors.

Figure 1.

Risk of sexual assault for various visual impairment (VI) characteristics in a population of people who are blind and visually impaired (n=736); results unadjusted (blue) and adjusted for age and gender (red).

In individuals with VI who had experienced sexual assaults, the mean scores (SD) were 29.8 (5.7) for self-efficacy and 5.8 (2.3) for life satisfaction. In individuals with VI who had not experience any sexual assaults, the mean scores (SD) were 31.7 (5.0) for self-efficacy and 6.9 (1.9) for life satisfaction. Results from the unadjusted GLMs showed that those who had been exposed to sexual assault had lower levels of self-efficacy (RR: 0.21, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.64) and life satisfaction (RR: 0.31, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.50) compared with those who had not been sexually assaulted. After adjusting for age, gender, education and VI severity, the associations remained statistically significant for both self-efficacy (RR: 0.18, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.61) and life satisfaction (RR: 0.33, 95% CI 0.20 to 0.53).

Discussion

The results from this cross-sectional study showed a higher prevalence of people in the VI population being exposed to sexual assaults such as being raped and forced into sexual acts compared with that in the general population, reaching statistical significance for women only. In the population of people with VI, the risk of sexual assaults was particularly high among individuals having other impairments in addition to their vision loss. Lastly, individuals with VI who had been assaulted sexually had lower levels of self-efficacy and life satisfaction compared with the reference of no sexual assaults.

Strengths and limitations

This is one of few studies addressing the prevalence and associated factors of sexual assaults by including a probability sample of adults with VI19 and extends previous research by obtaining valid estimates of sexual assaults across a broad array of age groups and including data obtained from the general population. Other study strengths are the detailed description of important VI characteristics and the use of interview-based assessments with validated instruments.

The cross-sectional observational study design limited the possibility to address relationships of cause and effect, and although we have controlled for some potentially confounding factors, it is plausible that our analyses are subjected to residual confounding. In addition, there may be differences in what people perceive or define as sexual assault. We believe that the specific examples of violent behaviours included in the study question made it easier for people to grasp what is meant by sexual assaults. Furthermore, the use of self-reports may have affected the accuracy and validity of the estimates, and the prevalence of sexual assaults could be underestimated as a function of response biases like recall bias and self-disclosure bias. Data on sexual assaults were obtained by telephone interviews in the VI population and by postal survey in the general population. Reviews of the literature suggest higher rates of sensitive information when reported by questionnaires than by interviews.28 29 Thus, the observed difference between people with VI and the general population may be a conservative estimate.

As in most studies focusing on sensitive topics,29 the high rates of people declining to participate from the VI population and the general population may have introduced biased estimates. We believe that the bias of sample selection have primarily affected the frequencies of sexual assaults and other covariates and, to a lesser extent, the relationships of interest.30 Lastly, inclusion of participants from a membership organisation of blind and visually impaired people questions the representativeness of our study sample. Our study sample is comparable with 2015 census data of people who had vision difficulties with regard to gender, occupational status and geographical location, while we included a higher percentage of people having higher education and living alone.31

Relation to other studies

The lifetime prevalence of sexual assaults in our study population is either equal to or lower than what has been found in comparable studies of blind and visually impaired populations in the USA (12%)19 or in Norway (18%).18 Furthermore, the results from our study are partly in agreement with the hypothesis of VI as a risk factor for experiencing serious forms of sexual violence.18 However, the low number of cases among men makes it difficult to draw inferences for the male population.

Our results of higher rates of sexual assaults in those having other functional impairments in addition to their VI illustrate that being markedly different from non-impaired people, and especially visibly different, may put individuals at risk of being exposed to certain forms of violence and abuse. Unlike the study by Kvam,18 we did not observe any significant associations between age of VI onset and sexual assaults.

We found a lower lifetime prevalence of sexual assault in adults 51 years or older compared with younger age groups. This deserves to be commented as we expected a cumulative exposure to assaults with increasing age. In addition to the possibility of recall bias and differences across age cohorts in attitudes towards violence,32 our findings may be explained by a high percentage of participants in older age groups who developed their VI in old age.13

Risk of sexual assault

Individuals with VI may be at risk of sexual assaults for many reasons, being either specific to VI itself or related to having an impairment in general. First, many people with VI are known to have lower socioeconomic status and to be more prone to social isolation and dependency.33 This makes it easier for a perpetrator to assert power and control over the victim.10 Being dependent on other people in care or service situations, which may be the case especially for some of those having additional impairments, may provide for closeness and intimacy.10 Often, the perpetrator has a close relationship to the victim. It has been found that 9 in 10 victims with VI were abused either by an acquaintance or a close relative.18 Important issues related to sexual violence are differences in power and control. Negative social views towards people with impairments, like stigmatisation and discrimination, may be internalised by the individual, leading to low self-esteem and feelings of self-blame.34 Dependency, fear of being left alone and feelings of unworthiness can make people stay in a relationship that is potentially abusive.

Self-efficacy and life satisfaction

To our knowledge, this is the first study addressing possible consequences of being exposed to sexual violence among individuals with VI. Our findings of an association between sexual assault and lower levels of self-efficacy or life satisfaction in adults with VI are similar to what has been observed in the general population2 35 36 and may have similar plausible explanations. Rape and forced sexual acts might cause deep-rooted consequences in various life domains, such as role management and the ability to socialise.37 Moreover, lower levels of self-efficacy and life satisfaction could be due to the fact that traumatic events like rape could affect people’s view of themselves, others and the world, as well as resulting in stress reactions like avoidance, low self-esteem, negative cognition and self-blaming.38 Self-efficacy is a key psychological component for restoring functioning and health after experiencing trauma and the ability to handle post-traumatic stress reactions is associated with self-efficacy beliefs in the future.36

Implications

The high prevalence of sexual assault in people with sensory impairments calls for preventive measures. Violence prevention strategies should try to raise public awareness, promote open discussion and upgrade professional education, service support and guidance.39 There is also a need for strategies that provide safe avenues through which people with VI can escape or recover after an assaulting event. Until now, few people with VI have prosecuted the perpetrator,18 and measures to intensify the legal protection of people with VI should be addressed.

Violence is largely about power and oppression.6 Impaired individuals’ risk of serious forms of sexual violence may be rooted in social isolation and being of a low social position. Thus, social integration of people with impairments should be a main objective to make them more robust towards sexual assaults, which can be achieved through universal design of information and public spaces, reducing stigmatisation and discrimination towards people with impairments and fostering self-reliance and independency of the individual.

Possible consequences of sexual assaults for self-efficacy and life satisfaction emphasise the need for professional assistance for those who have been abused. Access to help services are crucial, and adapted information and professionals trained to the needs and challenges of people with VI are recommended.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Marianne Bang Hansen for her contribution to the study design and data collection. We also want to thank Sverre Fuglerud, Per Fosse and Liv Berit Augestad for valuable insights into the lives of people who are blind and visually impaired. Lastly, we would like to thank the study expert group and all collaborating project partners in the European Network for Psychosocial Crisis Management – Assisting Disabled in Case of Disaster (EUNAD) for making it possible to conduct this research study.

Footnotes

Contributors: AB planned the statistical analysis, analysed and interpreted the data and drafted and revised the paper. TH designed the research study, monitored data collection for the whole study, cleaned the data, interpreted the data and drafted and revised the paper.

Funding: This work received grants from the European Commission, Directorate-General Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection (grant number: ECHO/SUB/2015/718665/PREP17).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study was carried out anonymously and at request the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics required no further formal ethical approval (reference number: 2016/1615A).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data are from the research project European Network for Psychosocial Crisis Management – Assisting Disabled in Case of Disaster (EUNAD). Public availability may comprise privacy of the respondents. According to the informed consent given by each respondent, the data are to be stored properly and in line with the Norwegian Law of Privacy Protection. However, anonymised data are available to researchers who provide a methodological sound proposal in accordance with the informed consent of the respondents. Interested researchers can contact project leader Trond Heir (trond.heir@medisin.uio.no) with request for our study data.

References

- 1. Walsh K, Galea S, Koenen KC. Mechanisms underlying sexual violence exposure and psychosocial sequelae: a theoretical and empirical review. Clin Psychol 2012;19:260–75. 10.1111/cpsp.12004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hughes K, Bellis MA, Hardcastle KA, et al. . The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health 2017;2:e356–66. 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30118-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Forouzanfar MH, Afshin A, Alexander LT, et al. . Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. The Lancet 2016;388:1659–724. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31679-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Welch J, Mason F. Rape and sexual assault. BMJ 2007;334:1154–8. 10.1136/bmj.39211.403970.BE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sugar NF, Fine DN, Eckert LO. Physical injury after sexual assault: findings of a large case series. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004;190:71–6. 10.1016/S0002-9378(03)00912-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sokoloff NJ, Dupont I. Domestic violence at the intersections of race, class, and gender: challenges and contributions to understanding violence against marginalized women in diverse communities. Violence Against Women 2005;11:38–64. 10.1177/1077801204271476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Abrahams N, Devries K, Watts C, et al. . Worldwide prevalence of non-partner sexual violence: a systematic review. Lancet 2014;383:1648–54. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62243-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rothman EF, Exner D, Baughman AL. The prevalence of sexual assault against people who identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual in the United States: a systematic review. Trauma Violence Abuse 2011;12:55–66. 10.1177/1524838010390707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hughes K, Bellis MA, Jones L, et al. . Prevalence and risk of violence against adults with disabilities: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Lancet 2012;379:1621–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61851-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Plummer SB, Findley PA. Women with disabilities’ experience with physical and sexual abuse: review of the literature and implications for the field. Trauma Violence Abuse 2012;13:15–29. 10.1177/1524838011426014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Colenbrander A. Assessment of functional vision and its rehabilitation. Acta Ophthalmol 2010;88:163–73. 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2009.01670.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. World Health Organization. ICD-10 Version:2016 [Internet]. 2018. http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2016/en [cited 05 Jan 2018].

- 13. Pascolini D, Mariotti SP. Global estimates of visual impairment: 2010. Br J Ophthalmol 2012;96:614–8. 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-300539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Solebo AL, Rahi J. Epidemiology, aetiology and management of visual impairment in children. Arch Dis Child 2014;99:375–9. 10.1136/archdischild-2012-303002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rosenberg T, Flage T, Hansen E, et al. . Incidence of registered visual impairment in the Nordic child population. Br J Ophthalmol 1996;80:49–53. 10.1136/bjo.80.1.49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rahi JS, Cumberland PM, Peckham CS. Improving detection of blindness in childhood: the British Childhood Vision Impairment study. Pediatrics 2010;126:e895–903. 10.1542/peds.2010-0498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Court H, McLean G, Guthrie B, et al. . Visual impairment is associated with physical and mental comorbidities in older adults: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med 2014;12:1–8. 10.1186/s12916-014-0181-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kvam MH. Experiences of childhood sexual abuse among visually impaired adults in Norway: prevalence and characteristics. JVIB 2005;99:5–14. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kelley SD, Moore J. Abuse and violence in the lives of people with low vision: a national survey. RE:view 2000;31:155–64. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Spencer N, Devereux E, Wallace A, et al. . Disabling conditions and registration for child abuse and neglect: a population-based study. Pediatrics 2005;116:609–13. 10.1542/peds.2004-1882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pava WS. Visually impaired persons’ vulnerability to sexual and physical assault. JVIB 1994;88:103–12. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rounds Jr. DL. Victimization of individuals with legal blindness: nature and forms of victimization. Behav Sci Law 1996;14:29–40. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. The Norwegian Association of the Blind and Partially Sighted. Om Blindeforbundet [About the Norwegian Association of the Blind and Partially Sighted] [Internet]. https://www.blindeforbundet.no/om-blindeforbundet ([Cited 05 Jan 2018]).

- 24. Schou-Bredal I, Heir T, Skogstad L, et al. . Population-based norms of the Life Orientation Test–Revised (LOT-R). International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology 2017;17:216–24. 10.1016/j.ijchp.2017.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gray MJ, Litz BT, Hsu JL, et al. . Psychometric properties of the life events checklist. Assessment 2004;11:330–41. 10.1177/1073191104269954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Leganger A, Kraft P, R⊘ysamb E. Perceived self-efficacy in health behaviour research: Conceptualisation, measurement and correlates. Psychol Health 2000;15:51–69. 10.1080/08870440008400288 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cantril H. A study of aspirations. Sci Am 1963;208:121–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bowling A. Mode of questionnaire administration can have serious effects on data quality. J Public Health 2005;27:281–91. 10.1093/pubmed/fdi031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tourangeau R, Yan T. Sensitive questions in surveys. Psychol Bull 2007;133:859–83. 10.1037/0033-2909.133.5.859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rothman KJ, Gallacher JE, Hatch EE. Why representativeness should be avoided. Int J Epidemiol 2013;42:1012–4. 10.1093/ije/dys223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Statistics Norway. Statistikkbanken [Statistics Norway Databank] [Internet]. Available from: https://www.ssb.no/statbank/ [cited 05 Jan 2018].

- 32. Luoma M-L, Manderbacka C. 2008. Breaking the taboo: overview of research phase Finland [Internet]. Brussel: European Commission; http://eige.europa.eu/gender-based-violence/resources/finland/breaking-taboo-overview-research-phase-finland [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lane M, Lane V, Abbott J, et al. . Multiple deprivation, vision loss, and ophthalmic disease in adults: global perspectives. Surv Ophthalmol 2018;63 10.1016/j.survophthal.2017.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hassouneh-Phillips D, McNeff E. “I Thought I was Less Worthy”: low sexual and body esteem and increased vulnerability to intimate partner abuse in women with physical disabilities. Sex Disabil 2005;23:227–40. 10.1007/s11195-005-8930-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jumper SA. A meta-analysis of the relationship of child sexual abuse to adult psychological adjustment. Child Abuse Negl 1995;19:715–28. 10.1016/0145-2134(95)00029-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Diehl AS, Prout MF. Effects of posttraumatic stress disorder and child sexual abuse on self-efficacy development. Am J Orthopsychiatry 2002;72:262–5. 10.1037/0002-9432.72.2.262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dillon G, Hussain R, Loxton D, et al. . Mental and physical health and intimate partner violence against women: a review of the literature. Int J Family Med 2013;2013:1–15. 10.1155/2013/313909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fifth Edition (DSM-5). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Pub, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Brown H. Safeguarding adults and children with disabilities against abuse [Internet] Strasbourg: European Council of Europe, 2003. Available from: https://rm.coe.int/16805a297e. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-021602supp001.pdf (163.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-021602supp002.pdf (83.6KB, pdf)