Abstract

Objectives

To assess the feasibility of delivering and evaluating a lifestyle programme for patients with colorectal cancer undergoing potentially curative treatments.

Study design

Non-randomised feasibility trial.

Setting

National Health Service (NHS) Tayside.

Participants

Adults with stage I–III colorectal cancer.

Intervention

The programme targeted smoking, alcohol, physical activity, diet and weight management. It was delivered in three face-to-face counselling sessions (plus nine phone calls) by lifestyle coaches over three phases (1: presurgery, 2: surgical recovery and 3: post-treatment recovery).

Primary outcome

Feasibility measures (recruitment, retention, programme implementation, achieved measures, fidelity, factors affecting protocol adherence and acceptability).

Secondary outcomes

Measured changes in body weight, waist circumference, walking and self-reported physical activity, diet, smoking, alcohol intake, fatigue, bowel function and quality of life.

Results

Of 84 patients diagnosed, 22 (26%) were recruited and 15 (18%) completed the study. Median time for intervention delivery was 5.5 hours. Coaches reported covering most (>70%) of the intervention components but had difficulties during phase 2. Evaluation measures (except walk test) were achieved by all participants at baseline, and most (<90%) at end of phase 2 and phase 3, but <20% at end of phase 1. Protocol challenges included limited time between diagnosis and surgery and the presence of comorbidities. The intervention was rated highly by participants but limited support from NHS staff was noted. The majority of participants (77%) had a body mass index>25 kg/m2 and none was underweight. Physical activity data showed a positive trend towards increased activity overall, but no other changes in secondary outcomes were detected.

Conclusions

To make this intervention feasible for testing as a full trial, further research is required on (a) recruitment optimisation, (b) appropriate assessment tools, (c) protocols for phase 2 and 3, which can build in flexibility and (d) ways for NHS staff to facilitate the programme.

Trial registration number

ISRCTN52345929; Post-results.

Keywords: prehabilitation, lifestyle intervention, colorectal cancer

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This feasibility study is the first to have offered a comprehensive lifestyle intervention programme at diagnosis with support before, during and after treatment in patients with colorectal cancer.

The study highlights the wide range of variables that need to be considered in designing a future randomised controlled trial (including recruitment and support from National Health Service (NHS) staff, complexities of patient health status and time required for permissions, assessment and interventions).

The lack of randomisation means it is not possible to estimate uptake to a randomised controlled trial.

The work was undertaken in a single NHS health board and may not be representative of other treatment centres.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) survival has improved in the last decade due to earlier diagnosis and new treatments but, in Scotland, survivors still have notable excess mortality within the first year postdiagnosis compared with other European countries.1 Survivors also have a high rate of pre-existing comorbidities and treatment-related symptoms. The latter are experienced by 15% undergoing colonic surgery, 33% with rectal surgery, 50% of those with chemoradiation therapy and 66% of patients undergoing short course radiotherapy. These symptoms include fatigue, physical discomfort and bowel function problems.2

In people diagnosed with cancer, it is recognised that smoking cessation, improved physical activity and diet have the potential to impact on treatment outcomes and cancer recurrence. A number of studies have reported that higher levels of physical activity are associated with better physical functioning3 and reduced fatigue,4 although further work is needed in this area.5 Follow-up studies report better disease-free, recurrence-free and overall survival in people who are more physically active.6 7 Intervention trials have shown that higher levels of physical activity initiated at prehabilitation (presurgery), postsurgery, during and after adjuvant therapies (rehabilitation)8–10 are associated with improved cardiorespiratory fitness, muscular strength, physical functioning, quality of life and reduced psychosocial distress.

There is growing evidence for the impact of diet on CRC cancer outcomes.11 A large observational study has reported that a higher level of a Western dietary intake (compared with a lower level of Westernisation) resulted in lower disease-free and overall survival rates.12 At intervention level, a trial of dietary counselling delivered during treatment13 showed that nutrition improvements were associated with reduced treatment related comorbidity (radiotherapy toxicity) at 3 months and after a mean follow-up of 6 years. Three post-treatment exploratory trials14–16 of combined lifestyle interventions have reported improved dietary behaviour, reduced fatigue, improved exercise tolerance, functional capacity and quality of life.

There is some evidence to support lifestyle interventions in the presurgical and post-treatment periods, but no trial has yet evaluated an intervention covering the full patient journey. Patients report confusion about appropriate lifestyle behaviours because they have received conflicting advice at different treatment stages and rarely receive personalised support in the period after treatments end and during return to normal health.17 It has been noted that relatively few patients with CRC stop smoking after diagnosis (13.7% prediagnosis to 9% 5 months later).18 Current data suggest that, in patients with CRC, physical activity levels drop significantly by 6 months postdiagnosis.19 This may reflect lack of consistent guidance from clinicians, and patient confusion over the merits of rest versus activity.20 Similarly, for diet, misconceptions exist over body weight gain (or loss) and understanding of appropriate food selection.

There are a number of behavioural frameworks that could support lifestyle change from the start of care such as the concept of the ‘teachable moment’.21 Cancer care clinicians, starting at diagnosis and throughout the cancer pathway, can be powerful advocates to help patients understand the importance of a healthy lifestyle and they have expressed interest in providing guidance.22 Patients consider information obtained from cancer specialists to be of the best quality.20 Despite major concerns over their diagnosis, many patients request advice on what might be done to prepare for surgery and there is a need for clinicians to identify an effective programme with the potential to improve health in the first year after diagnosis. Increasingly, asymptomatic patients are diagnosed via the national bowel screening programme, which means that this patient group is less frail than those diagnosed late and have considerable potential to initiate lifestyle change. Opportunities in the ‘prehabilitation’ period have been highlighted in cancer strategy documents,23 but little is known about likely uptake of interventions.

This study aimed to assess the practical aspects of delivering and evaluating a lifestyle intervention programme (TreatWELL) for patients with CRC undergoing potentially curative treatments in order to inform the feasibility of undertaking a randomised controlled trial (RCT) to assess the clinical and cost-effectiveness of this intervention at 1 year after diagnosis.

Specific objectives were to assess recruitment and retention to assist in the design of a future RCT, assess the feasibility of data collection procedures, ease of programme implementation, patient acceptability, fidelity and factors influencing adherence to the intervention.

Methods

Study design and setting

This study was a single-arm, two-centre feasibility study of the TreatWELL intervention programme carried out in tertiary level teaching hospitals in Tayside, UK.

Sample size

We aimed to recruit 34 participants in order to be able to assess feasibility objectives and to provide data to inform the sample size required to show significant differences in health outcome variables in a fully powered RCT. These numbers were based on a pragmatic assessment of patient numbers, eligibility and participation based on a previous study undertaken with the same patient group (at post-treatment stage) in the same geographic area.15

Eligibility

Eligible patients were adults aged >18 years, capable of giving informed consent, considered to have stage I–III colorectal cancer, eligible for potentially curative treatment (had to be fit for major surgery). It should be noted that participants were recruited before CT scans and eligibility was based on clinical examination. Patients who had severe cognitive impairment, emergency surgery or preoperative neoadjuvant therapy were excluded from the study.

Recruitment

Eligible patients were introduced to the study by a clinical nurse specialist (CNS) after discussing treatment and care plans following a cancer diagnosis. At this meeting, the CNS introduced the study and endorsed its importance for helping to achieve lifestyle change in the presurgical period. Interested patients were provided with a participant information sheet, an invitation and endorsement letter from the lead CRC clinician for Tayside and a prepaid opt-in reply slip, which they could return to the research team. A research nurse (RN) then contacted patients, who had either provided their contact details to the CNS or returned the prepaid reply slip, to discuss the study in detail and (if appropriate) make an appointment to obtain written informed consent and take baseline measurements. This appointment was held at the referring hospital or the participant’s home, if a hospital location was reported as a barrier to participation.

Intervention

The TreatWELL intervention programme aimed to facilitate collaboratively agreed behaviour changes towards achieving and maintaining smoking cessation, increased physical activity (to at least 150 min moderate-intensity activity per week), caloric intake appropriate to weight status and a nutrient-dense diet. All goals were consistent with the American Cancer Society and World Cancer Research Fund guidance for cancer survivors.24 25 The behavioural approaches were informed by two main theoretical frameworks: self-regulatory theory26 and the health action process approach.27

Following baseline measures, consented patients’ contact details were passed to a lifestyle coach (LC) who then commenced the TreatWELL personalised intervention. The LCs had a nursing background, experience with cancer patient management and underwent a 3-day bespoke training programme covering smoking cessation, increasing moderate physical activity, brief interventions on alcohol and weight management (postsurgical and post-treatment). The intervention was delivered via three face-to-face contacts (one per intervention phase and a minimum of nine phone calls) supported by written literature and a range of behavioural techniques.

Phase 1: prehabitation to start within 3–10 days of diagnosis to surgery.

Phase 2: surgical recovery to start 1 day postoperative and aim to complete within 21 days.

Phase 3: postsurgical/adjuvant therapy recovery to start 21 days postoperative for 25 weeks.

The total intervention period comprised 31 weeks, although duration was flexible as it was based on the individual’s treatment regimen. The delivery mode, consultation focus, resources and behaviour change techniques used in each phase are presented in online supplementary appendix 1. Decisions about phase completion (eg, defining the end of postsurgical recovery) and progression was agreed in conjunction with the CNS. In summary, each phase of the programme comprised verbal educational approaches with written resources (eg, booklets, resistance bands) and the use of behavioural techniques. Importantly, personalised, specific action goals were identified with a focus on two health behaviours that were selected as a priority for that individual (eg, smoking, physical activity). All participants were invited to engage a support person (eg, spouse) to assist in their adherence with the programme. It should be noted that the protocol for phase 3 varied according to chemotherapy use. For patients with no adjuvant therapy, the progression to addressing body weight issues (overweight, underweight and weight loss) was addressed at the start of this phase. For participants undergoing chemotherapy, the focus on diet and weight management was delayed to avoid any confusion that might arise with dietary issues related to treatment side effects (eg, nausea).

bmjopen-2017-021117supp001.pdf (125KB, pdf)

Participants were encouraged to develop personalised action and coping plans. Activities (eg, brisk walking) were demonstrated and tried by participants. Access to an equipment tool kit (pedometers, resistance bands and DVDs) was also offered. Emphasis was placed on self-monitoring and goal setting, for example, physical activity through pedometers, with weekly feedback in the first week of each phase. In phase 2, participants were encouraged to commence activity in accordance with ability, their postoperative condition and guidance from their healthcare team. In phase 3, the participant’s phase 1 plan was repeated and expanded to include an emphasis on core strength, mobility and functional ability, with a strict protocol for referral to a physiotherapist if there were any safety concerns.

In phase 1, advice for participants not at risk of malnutrition (body mass index (BMI)>20 kg/m2) focused on avoiding weight gain and increasing nutrient quality of their diet in line with the Department of Health Eatwell guide.28 Participants were also advised about decreasing alcohol intake, as appropriate. No energy prescription was set in phase 1. In phase 2 and initially in phase 3, nutrition advice focused on symptom management (eg, anorexia, vomiting and bowel problems) and worked towards achieving a nutrient-dense diet. In the later stage of phase 3, all participants (BMI>20 kg/m2) were given personalised guidance on a nutrient-dense diet and avoidance of excess weight gain. Participants with a BMI>25 kg/m2 were advised on avoidance of weight gain and modest weight reduction (>5% wt loss) using a personalised energy prescription goal. Communications emphasised the concept of building resilience through the combined approach of increasing muscle mass (through physical activity) and decreasing excess body fat (through caloric reduction). The importance of regular self-weighing was stressed and feedback provided at each telephone consultation.

Informed by behaviour change techniques used in previous interventions29 and the behaviour change wheel,30 a range of evidence-based behavioural techniques were employed to motivate and support lifestyle change. These included motivational interviewing, formation of specific implementation intentions, self-monitoring, personalised action and coping plans, feedback and re-enforcement.

Measurements

The research nurses prospectively collected details on sociodemographic background, clinical information (including tumour stage and site), type of surgery, stoma status, medications and details of adjuvant treatments.

Primary outcome measures

Recruitment and retention were assessed from research nurse records. Information on reasons why patients were ineligible or choose not to participate were recorded with patient consent.

Programme implementation (by LCs) was estimated from a structured pro forma completed after every patient contact which recorded actual values or scaled ratings on:

Intervention start time (days after diagnosis);

Total contact time;

Ease or difficulty of implementing the session;

Perceived fidelity to the intervention content;

Extent of patient engagement, receptivity and motivation.

Achieved measurements (by RNs) were recorded at baseline and the end of each phase of the study.

Participants’ views on acceptability of the intervention and factors influencing adherence were explored in in-depth qualitative interviews conducted by MS and JMcK. Interviews were scheduled for around 45–60 min and were conducted either face to face or by telephone. Interviews were digitally recorded with participants’ consent, and transcribed verbatim for analysis. The original intention was to interview a random sample of one in three participants at the end of phase 2 and another at the end of phase 3. However, because of the low number of participants everyone was invited to take part in an interview towards the end of their journey through the intervention programme.

Secondary outcome measures

Anthropometric measures were taken as follows:

Body weight measured with the participant wearing indoor clothing and no shoes, using a calibrated Seca 877 digital scale.

Height measured with a Seca Leicester portable stadiometer.

BMI was calculated as: weight (kg)/height (m)2.

Waist circumference measured with a Seca 201 measuring tape, with the participant in the standing position and the tape positioned midway between the lateral lower rib margin and the iliac crest. If these landmarks could not be identified, the measurement was taken at the level of the umbilicus. Two measurements were taken postexhalation and the mean recorded.

Smoking status was self-reported and alcohol intake was measured using 7-day alcohol recall31—units of alcohol consumed per week and number of alcohol free days per week were noted.

Dietary intake was measured using the Dietary Instrument for Nutrition Education questionnaire.32

Physical activity was assessed using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire short form33 and the 6 min walk test.34

Health outcomes of interest were explored—fatigue was measured using the multidimensional fatigue inventory-2035 and physical function and quality of life by the EORTC GLQ C30 Quality of Life questionnaire for patients with bowel cancer and the EORTC GLQ C29 Quality of Life questionnaire for patients with colorectal cancer.36 Bowel function was assessed by the Low Anterior Resection Syndrome Score (LARS).37

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics allowed characterisation of the cohort. Outcome measures were assessed for completeness but no statistical analysis was undertaken given the small sample, which was not powered to show definitive results.

Data from proformas completed by the LC were analysed by descriptive statistics (mean±SD) to estimate completeness of delivery and areas for improvement, and to provide contextual information (including National Health Service (NHS) service issues) on patient engagement.

Data from the transcripts were coded by MS and JMcK using a framework approach,38 with an initial framework developed around different aspects of engagement in the study and intervention: recruitment and delivery acceptability, engagement with lifestyle change, facilitators and barriers to lifestyle change and any issues that would need to be considered if conducting a full RCT. The framework was revised to incorporate additional themes, which emerged from the transcripts (eg, concerning physical activity (PA) goals and conflicting advice given by other health professionals).

Patient and public involvement

The Chair of Tayside Cancer Patient and Public Involvement Group provided guidance on project development and progression. The group also identified a potential patient representative who subsequently assisted in reading and commenting on study design, communication materials and specific questions. Guidance was requested from the patient representative on sensitive communications regarding body weight and introducing the topic. Patients were not involved in study recruitment.

We have no plans to disseminate the results of this feasibility work to participants.

Results

Recruitment and retention

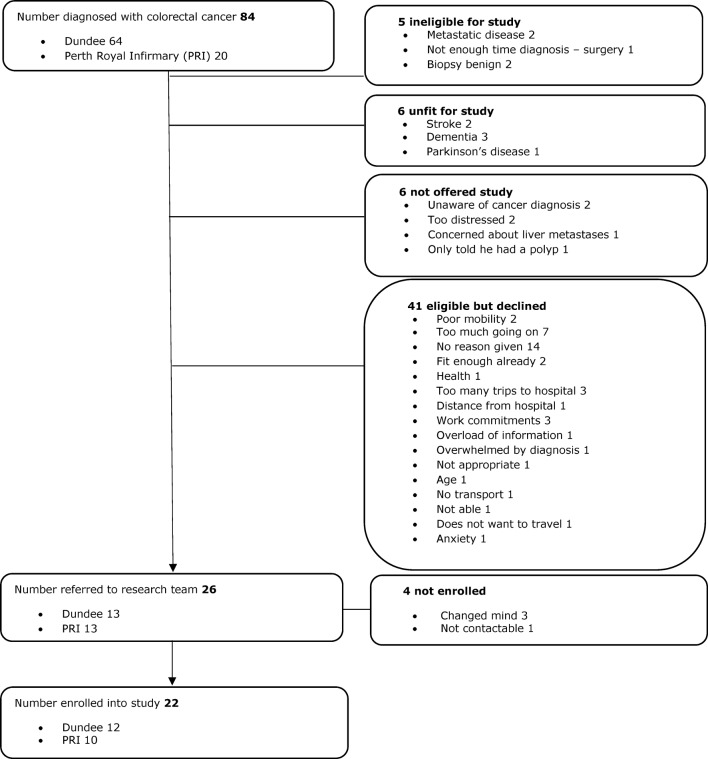

Over the 7-month recruitment period (01.04.14 to 31.10.14), the number of patients diagnosed and recorded with colorectal cancer was 84 and 22 (26%) were recruited to the study (figure 1). Of the remainder, 17 were ineligible, unfit or not approached to participate and 45 declined to take part, the most common reason was the extra burden of the study. It should be noted that because of the short window for intervention, some participants were recruited before CT scans were complete. In one case, lung metastases were diagnosed after CT staging. Surgery was still undertaken for this patient on the clinical basis that it had the potential to improve survivorship.

Figure 1.

TreatWELL recruitment Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials flow chart.

The median age of non-participants was 74 (range 44–90 years) and 49% were male (table 1). Of the 22 who were recruited, the mean age was 67 years and 77% were male. Baseline data on BMI and key health behaviours (smoking, physical activity, alcohol and diet score) indicate significant potential for health gain.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics by completion*

| Recruited n=22 | Completed n=15 | Dropped out/lost to follow-up n=7 | |

| Male gender | 17 (77%) | 11 (73%) | 6 (86%) |

| Age: median (Lower Quartile [LQ], Upper Quartile [UQ]) | 67.0 (60.0, 74.3) | 66.0 (60.0, 72.0) | 75.0 (64.0, 80.0) |

| Baseline BMI (kg/m2): median (LQ, UQ) | 28.3 (25.5, 33.5) | 28.6 (26.1, 33.6) | 25.8 (24.1, 32.6) |

| SIMD category | |||

| 1–3 (most deprived) | 5 (23%) | 4 (27%) | 1 (14%) |

| 4–7 | 10 (45%) | 7 (46%) | 3 (43%) |

| 8–10 (most affluent) | 7 (32%) | 4 (27%) | 3 (43%) |

| Smoking status | |||

| Current | 2 (9%) | 1 (7%) | 1 (14%) |

| Ex-smoker | 14 (64%) | 10 (67%) | 4 (57%) |

| Never smoked | 6 (27%) | 4 (26%) | 2 (28%) |

| Treatments | |||

| Chemotherapy and radiotherapy | 3 (14%) | 2 (13%) | 1 (14%) |

| Chemotherapy only | 6 (27%) | 5 (33%) | 1 (14%) |

| No oncology | 10 (45%) | 8 (53%) | 2 (29%) |

| Palliative care | 3 (14%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (43%) |

| Cancer staging | |||

| Duke A | 3 (14%) | 3 (20%) | 0 (0%) |

| Duke B | 6 (27%) | 3 (20%) | 3 (42%) |

| Duke C | 8 (36%) | 6 (40%) | 2 (29%) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 2 (9%) | 2 (13%) | 0 (0%) |

| Well-differentiated neuroendocrine | 1 (5%) | 1 (7%) | 0 (0%) |

| Metastases | 2 (9%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (29%) |

| Behaviours impacting on cancer risk | |||

| Smoker: n (%) | 2 (9%) | 1 (7%) | 1 (14%) |

| Alcohol consumers: n (%) | 15 (68%) | 10 (67%) | 5 (71%) |

| Alcohol consumption (units per week): median (LQ, UQ) Range |

10 (4, 22) 1–70 |

12.5 (3.75, 53.25) 3–70 |

11.0 (~)† ~ |

| Alcohol free days: median (LQ, UQ) Range |

4 (1, 5) 0–6 |

3.5 (1.0, 5.0) 0–6 |

0 (~)† ~ |

| Leisure PA (min): median (LQ, UQ) Range |

480 (227, 709) 40–2070 |

480 (240, 705) 40–2070 |

480 (190, 735) 150–1030 |

| Work PA (min): median (LQ, UQ) Range |

1800 (163, 4200) 125–4800 |

200 (~)‡ 125–4800 |

2700 (~)‡ 1800–3600 |

| Total PA (work+leisure): median (LQ, UQ) Range |

532 (228, 886) 40–5250 |

480 (240, 720) 40–5250 |

649 (190, 2830) 150–4080 |

| Fat rating score: median (LQ, UQ) Range |

32.0 (26.75, 41.25) 16–64 |

32.0 (27.0, 42.0) 17–64 |

29.0 (26.0, 37.0) 16–44 |

| Fibre rating score: median (LQ, UQ) Range |

30.5 (25.5, 40.0) 10–50 |

31.0 (28.0, 40.0) 10–50 |

27.0 (24.0, 40.0) 15–40 |

*All results are n (%) unless stated otherwise.

†n=1.

‡<4 participants in work.

BMI, body mass index; SIMD, Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation.

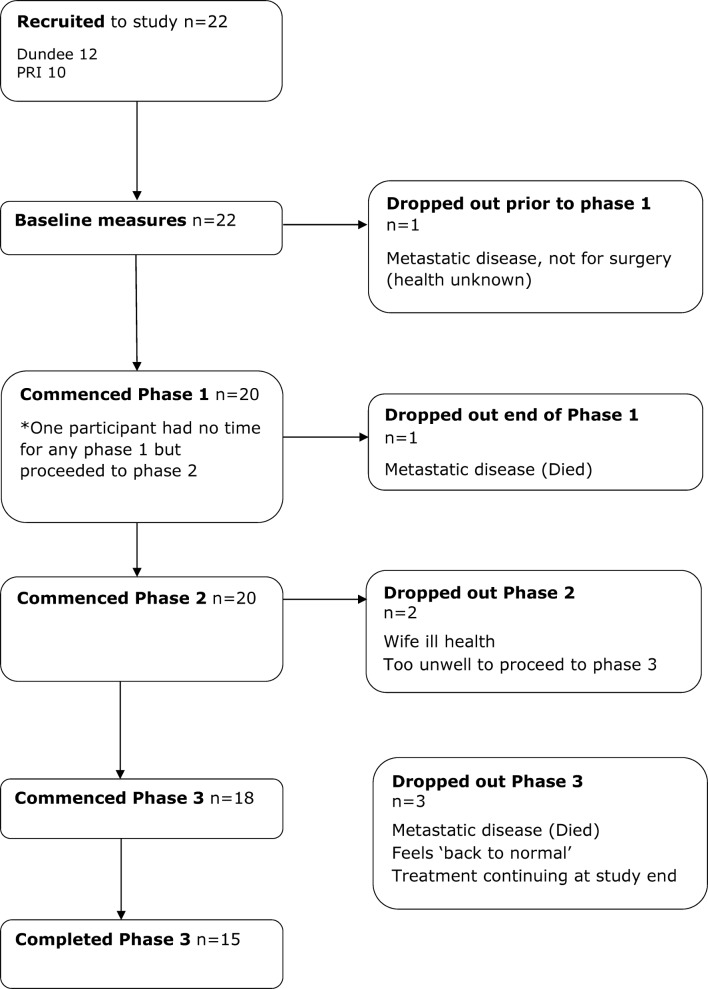

In total, 15 (68%) completed the study (figure 2). The main reason for drop out at all stages was major ill health.

Figure 2.

TreatWELL study progression CONSORT flow chart.

Programme implementation

The median time in phase 1 (prehabilitation) was 15 days. The median time in phase 2 was 36.5 days and phase 3 was 102 days but was frequently extended by clinical problems due to health status postsurgery, treatment responses and pre-existing comorbidities. Table 2 illustrates the significant and varied challenges experienced by individual participants during the recovery phase. Many patients did not have sufficient time in phase 3 (prior to project end) to enable secondary outcomes to be reliably assessed.

Table 2.

Summary of participants’ clinical progress during the TreatWELL study

| 1 | Biopsy showed advanced disease after patient had undergone baseline measures and the phase 1 LC intervention visit. Patient excluded from further study measures. |

| 2 | Surgery as planned but poor postoperative recovery and discharged to a continuing care unit. Intravenous chemotherapy started after discharge home followed by oral chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Waiting for stoma reversal. All phases of study completed. |

| 3 | Surgery as planned. Slow recovery postsurgery and on parenteral nutrition. No adjuvant therapies required. Discharged home with carers twice a day, walking with a Zimmer frame. May have further surgery and did not progress beyond phase 2 in study. Seen at peripheral hospital. |

| 4 | Surgery as planned. No adjuvant therapies required. Became worried about recurrence after discharge and had to have psychological support. Hip pain restarted in phase 3. Lung metastases and heart failure diagnosed. Dropped out during phase 3. Patient died. |

| 5 | Surgery as planned. No adjuvant therapies required. All study phases completed. |

| 6 | Short phase 1. Emergency surgery to defunction bowel (stoma formation). Successful chemotherapy and radiotherapy before main surgery. Phases 2 and 3 switched round for this participant. All study phases completed. |

| 7 | Surgery as planned then admission to high dependency unit postoperatively. Discharged but readmitted for further surgery and stoma formation. Chemotherapy given. All study phases completed. |

| 8 | Surgery performed. Further surgery performed for removal of residual tumour. Stoma reversed. No adjuvant therapies required. All study phases completed. |

| 9 | Biopsy showed advanced disease after patient had undergone baseline measures. Patient not going ahead for surgery and excluded from further study measures. |

| 10 | Surgery as planned and chemotherapy. Admitted with diabetic ketoacidosis but diabetes since resolved. Slow recovery. Phase 1 delivered day before surgery. Phase 2 and 3 of study completed. |

| 11 | Short phase 1. Surgery performed. No adjuvant therapies required. Completed phase 2 and 3 of the study. |

| 12 | Phase 1 delivered day before surgery. Surgery performed. Chemotherapy commenced early due to cancellation in clinic and completed. Phase 2 completed. Wife has health issues that prevented him completing phase 3. |

| 13 | Surgery as planned, No adjuvant therapies required. All phases of study completed. Home visits. |

| 14 | Surgery as planned and chemotherapy started after surgery. All study phases completed. Seen at peripheral hospital. |

| 15 | Surgery as planned and no chemotherapy required. All phases of study completed (short phase 1). Home visits. |

| 16 | Surgery as planned, no adjuvant therapies required. All phases of study completed. Home visits. |

| 17 | Surgery as planned. Oral chemotherapy after surgery. All phases of study completed. |

| 18 | For defunctioning stoma and presurgery radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Surgery performed. Lost to follow-up as still requiring intensive treatment at study end (phase 1 and 2 only). |

| 19 | Surgery as planned but readmitted. Slow recovery from surgery with significant complications. Phase 1, 2 and 3. Dropped out of study during phase 3 as felt back to normal and did not require further support. |

| 20 | No phase 1 undertaken. Surgery as planned, long postoperative recovery. No adjuvant therapies required. Phase 2 and 3 of study completed. |

| 21 | Surgery performed. No adjuvant therapies required. All phases of study completed. Home visits. |

| 22 | Phase 1 delivered day before surgery. Surgery performed. Chemotherapy required. Phase 2 and 3 of study completed. |

Participant completed study n=15. Dropped out n=7.

Total median intervention delivery by lifestyle counsellors was 5 hours 29 mins. LCs reported that patient engagement was high, with 93%–100% being at least ‘fairly engaged’ at all stages. Similarly, the LCs reported that participants were receptive and interested in the information being delivered.

LCs rated participants as at least ‘fairly motivated’ to improve diet and physical activity levels. During the immediate recovery stage (phase 2), LCs were most likely to report goal setting for diet and PA as ‘neither easy nor difficult’ (73% and 64% for diet and PA, respectively). At the phase 3a time point, LCs rated the ease of goal setting more favourably, with 46% of consultations described as ‘easy’ to set dietary goals and 82% for PA.

Achieved measurements

Baseline measures were completed on all participants, except in four cases, where the 6 min walk test had to be excluded due to lack of space in the participant’s home. Only 6 out of 33 participants were seen at the end of phase 1 due to the difficulty in fitting in visits prior to surgery. All participants remaining in the study were seen at the end of phase 2, but it was not possible to carry out all anthropometric measurements and walking tests at this point. Walking tests were not possible at the end of phase 3. Questionnaire data were generally well completed; however, some participants were reluctant to answer sexual function questions (LARS questionnaire) in all phases.

Factors affecting protocol adherence

The LCs reported that they were able to cover most of the intervention components during phase 1 (78% delivery), 3a (73% delivery) and 3b (90% delivery). However, during the postsurgical phase (phase 2), LCs reported difficulties with access to patients. Lifestyle counselling was reported as most challenging during visits 1 (first contact) and 2 (immediately postsurgery). Delivery became more comfortable towards the end, with LCs reporting 70% of the final sessions as ‘fairly easy’ (compared with 39% in phase 1 and 46% in phase 2).

The major challenges of intervention delivery reported by the LCs were:

The short time between diagnosis and surgery;

Participants identifying time to fit in the baseline and intervention visits in addition to diagnostic and treatment preparation schedules;

Seeing patients in phase 2 (short period);

Difficulties identifying the transition from end of phase 2 and start of phase 3;

Poor clinical progress (some patients were readmitted);

Due to complications, a longer treatment period was required that extended phase 3 beyond the project life;

Mixed messages from NHS staff and TreatWELL LCs.

Participants views on acceptability

Of 20 participants who completed phase 2II, 14 were invited for interview, 3 declined and 11 participated (7 men and 4 women), with a mean age of 66±6 (range 57–75) years. Interviewees were from a range of areas of deprivation.

Most participants recalled that they had been recruited around the time of their diagnosis. For some, this timing appeared to have facilitated participation, as the study offered a potentially beneficial experience on which to focus, taking their mind off their diagnosis and concerns for the future. Several were reassured by the endorsement of colorectal consultants. Generally, the amount of contact, and the balance between visits and telephone calls, appeared acceptable, and the provision of home visits was particularly appreciated. Some appeared a little apprehensive about the prospect of ‘going it alone’ at the end of the study but they recognised that its end signalled another milestone in their recovery. Participants spoke positively of LCs and felt that LCs had been able to move them gently into doing things they might have been reluctant to do. Some hinted that they had relied on the counsellor for wider emotional support.

The PA advice appeared to have been particularly salient, with most participants being able to describe their PA goals and targets. Pedometers were felt to have been very helpful. Some described having become so fixed on their PA goals that they ‘over-did things’, but most felt that the advice had encouraged them to be more active and to ‘push’ themselves more than they might otherwise have done. Participants generally felt that they had managed to take on board the diet advice, although some had struggled with cutting out ‘treats’.

A number of facilitators and barriers to engagement were identified. Prior enjoyment of walking and previous experience of weight loss programmes were both beneficial, as were supportive family members who encouraged adherence to healthy eating and sometimes participated in activity along with the participant. Receiving a diagnosis of cancer was a major motivator for adherence. Participants were determined to overcome their diagnosis and quickly regain their health, not least for significant others. Similarly, participants were motivated to make changes in order to put themselves in the best condition for surgery and to optimise their recovery. One woman was motivated to maintain a healthy weight during her stay in hospital by witnessing fellow patients who were overweight struggling with their mobility. Monitoring progress especially with regard to levels of PA also provided motivation and some enjoyment for participants.

A main factor which negatively affected adherence to the intervention was participants’ physical health. Some participants felt too unwell to increase PA, although this was alleviated for some by building strength gradually, while others described comorbidities hampering their attempts to be physically active.

Some clinical staff were reported to have advised participants to gain weight by eating whatever they liked and by not discouraging unhealthier foods, in direct contrast to TreatWELL. This inconsistency caused confusion, and participants reported following the advice of clinical staff. Participants also highlighted that NHS staff had little awareness of TreatWELL and appeared to provide little encouragement. More generally, it was noted that nursing staff did not encourage patients to get up and move on the ward.

Secondary outcomes

There was no change in smoking habits—one of the two smokers at baseline was lost to follow-up and the other smoker continued to smoke. The number of participants who reported consuming alcohol decreased between baseline and end of phase 3, although in some individuals intake increased. PA data show a positive trend towards increased activity overall. For the 15 who completed the study, minutes of physical activity nearly doubled from a median of 480 (IQ range 240–720) per week to 840 (IQ range 330–1260). This was largely due to an increase in leisure time activities, but, a decrease in active time at work (few participants continued to work during the study period). Dietary data indicated no increase in total fat score but a desirable increase in fibre score. Quality of life data indicated some increase in global health function but also increases in anxiety.

The majority of participants had excess weight (77%) and 40% were obese at baseline (table 1). None was underweight. At the end of phase 2II, body weight had decreased as expected in the postsurgical period. Despite this weight loss, no underweight individuals were detected at the end of phase 3 and the proportion with excess weight remained. The 6 min walk test indicated no decrease in functional ability by the end of phase 3.

It should be noted however that all secondary outcome results were obtained principally to test ability to undertake measures and are not powered to detect differences.

Discussion

While it is recognised that presurgical (prehab) lifestyle intervention may have significant impact on improving health outcomes in the early months following a diagnosis of colorectal cancer, there is little evidence of multicomponent intervention RCTs to support investment in this area. This study illustrates the complexities of delivering and evaluating such interventions and highlights issues that need to be addressed prior to progressing further work. The main findings show that it is difficult to recruit at diagnosis because of the multitude of investigations taking place, the staff’s perceptions of frailty and age (although all participants were deemed fit for surgery) and the relatively short period available for recruitment, baseline data collection and intervention delivery before surgery. It is notable that a high proportion of participants were male (77%) and while national data report39 that more men are diagnosed with colorectal cancer compared with women (54% vs 46%), the proportion in this study is higher than anticipated. The reason for this is not clear but does indicate the need to explore this in future work. Phase 2 was predictably short for most patients, but longer in those who had previous illness or had developed postsurgical complications. It should be noted that because patients were recruited at diagnosis, the extent of the disease (ie, stage) was unknown and complications were unpredictable. Many participants spent insufficient time in phase 3 (prior to study end) for the impact of the intervention to be assessed, highlighting the need for a longer study duration for final outcome measurements. The clinical pathways of participants were unpredictable and impacted on study retention. The hardest challenge in delivery was when to introduce the next phase of the intervention (phase 2 to phase 3) because many participants had complex journeys through treatment. These findings highlight that compliance with a strict RCT protocol for this type of intervention is likely to be difficult. Outcome measures were largely acceptable, although consideration should be given to whether the more sensitive questions on quality of life are required. Participant views suggest the intervention was largely acceptable, and that the focus on physical activity was appropriate. The high number of patients with excess body weight at study recruitment (and exit) is of concern and a future trial encompassing weight loss is likely to need long-term support and follow-up.

While our recent intervention study40 has tested the feasibility of undertaking lifestyle interventions in people at high risk of colorectal (and breast) cancer, this study (to the best of our knowledge) is the first to have offered a comprehensive lifestyle intervention at diagnosis with support before, during and after treatment in patients with colorectal cancer. Although the study is small and was undertaken in a single NHS health board, the results have highlighted a wide range of issues that would need to be addressed in a full trial of a multicomponent intervention. The lack of randomisation means that it is not possible to assess whether uptake to an RCT with control condition would be similar.

Moug et al 41 have recently reviewed 14 RCTs in this patient group and concluded that lifestyle interventions are feasible in patients with CRC. However, it is notable that there were no RCTs of tobacco and alcohol. In general, they reported variable recruitment rates but good adherence and retention (as is the case in our own study). Ravasco et al 13 have demonstrated positive outcomes in patients with CRC referred for radiotherapy (irrespective of other therapies provided) after dietary counselling. However, other trials of diet and lifestyle have been focused on patients after the end of treatment.14 42 43 The challenges to conducting a trial in this patient group are similar to those described by Hubbard et al 44 in feasibility work of a pragmatic RCT for a group-based rehabilitation programme for CRC survivors, which reported a high likelihood of recruitment bias, potential of suboptimal completion of outcome data, missing data and poor intervention adherence.

It is important to note that no specific progression criteria were identified (or agreed) for trial progression in the current study, but each of the parameters identified are relevant in decisions around future progression (recruitment, retention, programme implementation, achieved measures, fidelity, factors affecting protocol adherence and acceptability). The findings show that the recruitment was too low (both due to eligibility, people approached and willingness to participate), too many participants failed to complete because of major health problems, the intervention delivery varied widely from the protocol (in terms of timing and approaches) and the number of achieved measures (notably at end of phase 1) would be inadequate to provide any indication of impact.

In accordance with the study by Thabane et al, 45 there are four possible progression outcomes as follows: (i) Stop main study not feasible;(ii) Continue, but modify protocol feasible with modifications;(iii) Continue without modifications, but monitor closely feasible with close monitoring and(iv) Continue without modifications feasible as is.

Our results suggest that it would be plausible to continue but that the protocol should be modified and further feasibility testing undertaken prior to a full trial.

The current intervention approach is ambitious, but could be refined for testing in an RCT if all visits can be linked more closely with clinical appointments, measurement visits are reduced and if the clinical team were encouraged to help support lifestyle changes. Fundamentally, interventions being tested should be scalable, durable and cost-effective.46 While there is much practical guidance on diet and lifestyle for cancer survivors47 48 and interventions that have been demonstrated to be safe and feasible, there remains a need for studies that can demonstrate the impact of lifestyle intervention on disease outcomes. Research in this area requires multilevel approaches with full support from health service staff (both in recruitment and support for lifestyle action), intervention staff for the delivery of tailored, personalised approaches and patient interest and advocacy.

Conclusions

To make this intervention feasible for testing as a full RCT, further research is required on (a) recruitment optimisation, (b) appropriate assessment tools, (c) protocols for phase 2 and 3 that can build in flexibility and (d) ways for NHS staff to facilitate the programme.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants of this study, lifestyle coaches Catherine Savage and Carol Baird and the study administrator Jill Hampton who arranged the interviews and FGDs. The authors would also like to thank patient adviser Glynnis Marra and Alison Harrow, Tayside Cancer Patient and Public Involvement Group, for their expert guidance.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors have made substantial contributions to the study conception and design, and the development and editing of the manuscript. MM led initial study design and development, assisted with data collection, carried out the analyses and drafted the initial draft manuscript; RJCS had the initial concept and led initial study design and development; REO’C led the fidelity assessments (development and analyses) and provided guidance on project progression; MW had the initial concept and led initial study design and development; AC contributed to study design; JAS carried out the day-to-day management of the study and led the data collection; JR contributed to study design; MS and JMcK led on qualitative assessments (development and analyses); ASA had the initial concept and led initial study design and development, contributed to data analyses and had oversight of the study. All authors have read, edited and approved the manuscript for publication.

Funding: Funding for this study was provided by the Chief Scientist Office (CZH/4/939).

Disclaimer: The funder played no part in the design, execution or decision to publish this research.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was provided by the East of Scotland Research Ethics Service, REC reference no. 13/ES/0153.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Technical appendix, statistical code and dataset available from the authors on request.

References

- 1. The EUROCARE-4 database on cancer survival in Europe. http://www.eurocare.it/Results/tabid/79/Default.aspx (accessed Oct 2017).

- 2. Andreyev HJ, Davidson SE, Gillespie C, et al. Practice guidance on the management of acute and chronic gastrointestinal problems arising as a result of treatment for cancer. Gut 2012;61:179–92. 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Johnson BL, Trentham-Dietz A, Koltyn KF, et al. Physical activity and function in older, long-term colorectal cancer survivors. Cancer Causes Control 2009;20:775–84. 10.1007/s10552-008-9292-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Peddle CJ, Au HJ, Courneya KS. Associations between exercise, quality of life, and fatigue in colorectal cancer survivors. Dis Colon Rectum 2008;51:1242–8. 10.1007/s10350-008-9324-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brandenbarg D, Korsten J, Berger MY, et al. The effect of physical activity on fatigue among survivors of colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer 2018;26 10.1007/s00520-017-3920-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Meyerhardt JA, Giovannucci EL, Holmes MD, et al. Physical activity and survival after colorectal cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:3527–34. 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.0855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Haydon AM, Macinnis RJ, English DR, et al. Effect of physical activity and body size on survival after diagnosis with colorectal cancer. Gut 2006;55:62–7. 10.1136/gut.2005.068189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mayo NE, Feldman L, Scott S, et al. Impact of preoperative change in physical function on postoperative recovery: argument supporting prehabilitation for colorectal surgery. Surgery 2011;150:505–14. 10.1016/j.surg.2011.07.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Timmerman H, de Groot JF, Hulzebos HJ, et al. Feasibility and preliminary effectiveness of preoperative therapeutic exercise in patients with cancer: a pragmatic study. Physiother Theory Pract 2011;27:117–24. 10.3109/09593981003761509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pinto BM, Papandonatos GD, Goldstein MG, et al. Home-based physical activity intervention for colorectal cancer survivors. Psychooncology 2013;22:54–64. 10.1002/pon.2047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Van Blarigan EL, Meyerhardt JA. Role of physical activity and diet after colorectal cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:1825–34. 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.7799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Meyerhardt JA, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis D, et al. Association of dietary patterns with cancer recurrence and survival in patients with stage III colon cancer. JAMA 2007;298:754–64. 10.1001/jama.298.7.754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ravasco P, Monteiro-Grillo I, Camilo M. Individualized nutrition intervention is of major benefit to colorectal cancer patients: long-term follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of nutritional therapy. Am J Clin Nutr 2012;96:1346–53. 10.3945/ajcn.111.018838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bourke L, Thompson G, Gibson DJ, et al. Pragmatic lifestyle intervention in patients recovering from colon cancer: a randomized controlled pilot study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2011;92:749–55. 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.12.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Anderson AS, Caswell S, Wells M, et al. "It makes you feel so full of life" LiveWell, a feasibility study of a personalised lifestyle programme for colorectal cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 2010;18:409–15. 10.1007/s00520-009-0677-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hawkes AL, Gollschewski S, Lynch BM, et al. A telephone-delivered lifestyle intervention for colorectal cancer survivors ‘CanChange’: a pilot study. Psychooncology 2009;18:449–55. 10.1002/pon.1527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Anderson AS, Steele R, Coyle J. Lifestyle issues for colorectal cancer survivors-perceived needs, beliefs and opportunities. Support Care Cancer 2013;21:35–42. 10.1007/s00520-012-1487-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Park ER, Japuntich SJ, Rigotti NA, et al. A snapshot of smokers after lung and colorectal cancer diagnosis. Cancer 2012;118:3153–64. 10.1002/cncr.26545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hawkes AL, Lynch BM, Youlden DR, et al. Health behaviors of Australian colorectal cancer survivors, compared with noncancer population controls. Support Care Cancer 2008;16:1097–104. 10.1007/s00520-008-0421-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Anderson AS, Caswell S, Wells M, et al. Obesity and lifestyle advice in colorectal cancer survivors - how well are clinicians prepared? Colorectal Dis 2013;15:949–57. 10.1111/codi.12203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Demark-Wahnefried W, Aziz NM, Rowland JH, et al. Riding the crest of the teachable moment: promoting long-term health after the diagnosis of cancer. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:5814–30. 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mills ME, Davidson R. Cancer patients’ sources of information: use and quality issues. Psychooncology 2002;11:371–8. 10.1002/pon.584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Department of Health (2013). National Cancer Survivorship Initiative (NCSI). Living with and beyond Cancer: Taking Action to Improve Outcomes. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/181054/9333-TSO-2900664-NCSI_Report_FINAL.pdf

- 24. World Cancer Research Fund International (WCRF). Cancer Prevention Recommendations. http://www.wcrf.org/int/research-we-fund/cancer-prevention-recommendations/cancer-survivors (accessed Oct 2017).

- 25. Rock CL, Doyle C, Demark-Wahnefried W, et al. Nutrition and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2012;62:242–74. 10.3322/caac.21142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Leventhal H, Leventhal EA, Breland JY. Cognitive science speaks to the "common-sense" of chronic illness management. Ann Behav Med 2011;41:152–63. 10.1007/s12160-010-9246-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schwarzer R. Modeling health behaviour change: how to predict and modify the adoption and maintenance of health behaviors. Appl Psychol 2008;57:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Public Health England. The Eatwell Guide. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-eatwell-guide

- 29. Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med 2013;46:81–95. 10.1007/s12160-013-9486-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci 2011;6:42 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Emslie C, Lewars H, Batty GD, et al. Are there gender differences in levels of heavy, binge and problem drinking? Evidence from three generations in the west of Scotland. Public Health 2009;123:12–14. 10.1016/j.puhe.2008.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Roe L, Strong C, Whiteside C, et al. Dietary intervention in primary care: validity of the DINE method for diet assessment. Fam Pract 1994;11:375–81. 10.1093/fampra/11.4.375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2003;35:1381–95. 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Butland RJ, Pang J, Gross ER, et al. Two-, six-, and 12-minute walking tests in respiratory disease. Br Med J 1982;284:1607–8. 10.1136/bmj.284.6329.1607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. EORTC Quality of Life Department. QLQ-C30 questionnaire. http://groups.eortc.be/qol/eortc-qlq-c30 (accessed Oct 2017).

- 36. Smets EM, Garssen B, Bonke B, et al. The Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. J Psychosom Res 1995;39:315–25. 10.1016/0022-3999(94)00125-O [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Emmertsen KJ, Laurberg S. Low anterior resection syndrome score: development and validation of a symptom-based scoring system for bowel dysfunction after low anterior resection for rectal cancer. Ann Surg 2012;255:922–8. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31824f1c21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, et al. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:117 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Scottish Government Cancer Statistics. http://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/Cancer/Cancer-Statistics/Colorectal/#colorectal (accessed 7 Feb 2018).

- 40. Anderson AS, Dunlop J, Gallant S, et al. Feasibility study to assess the impact of a lifestyle intervention (’LivingWELL’) in people having an assessment of their family history of colorectal or breast cancer. BMJ Open 2018;8:e019410 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Moug SJ, Bryce A, Mutrie N, et al. Lifestyle interventions are feasible in patients with colorectal cancer with potential short-term health benefits: a systematic review. Int J Colorectal Dis 2017;32:765–75. 10.1007/s00384-017-2797-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Campbell MK, Carr C, Devellis B, et al. A randomized trial of tailoring and motivational interviewing to promote fruit and vegetable consumption for cancer prevention and control. Ann Behav Med 2009;38:71–85. 10.1007/s12160-009-9140-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Morey MC, Snyder DC, Sloane R, et al. Effects of home-based diet and exercise on functional outcomes among older, overweight long-term cancer survivors: RENEW: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009;301:1883–91. 10.1001/jama.2009.643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hubbard G, O’Carroll R, Munro J, et al. The feasibility and acceptability of trial procedures for a pragmatic randomised controlled trial of a structured physical activity intervention for people diagnosed with colorectal cancer: findings from a pilot trial of cardiac rehabilitation versus usual care (no rehabilitation) with an embedded qualitative study. Pilot Feasibility Stud 2016;2:51 10.1186/s40814-016-0090-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Thabane L, Ma J, Cheng J, et al. A Tutorial on pilot Studies;The What, Why and How. BMC Reseach Methodol 2006;10:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Demark-Wahnefried W, Rogers LQ, Alfano CM, et al. Practical clinical interventions for diet, physical activity, and weight control in cancer survivors. CA Cancer J Clin 2015;65:167–89. 10.3322/caac.21265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF). Cancer Prevention recommendations-People living with and beyond cancer. https://www.wcrf-uk.org/uk/preventing-cancer/cancer-prevention-recommendations/people-living-and-beyond-cancer (accessed Oct 2017).

- 48. American Cancer Society. https://www.cancer.org/treatment/survivorship-during-and-after-treatment/staying-active/nutrition/nutrition-and-physical-activity-during-and-after-cancer-treatment.html accessed Oct 2017

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-021117supp001.pdf (125KB, pdf)