Abstract

Purpose

The Coronary Artery disease Risk Determination In Innsbruck by diaGnostic ANgiography (CARDIIGAN) cohort is aimed to gain a better understanding of cardiovascular risk factors and their relation to the diagnosis and severity of coronary artery disease, as well as to the long-term prognosis in consecutive (including revascularised) patients referred for elective coronary angiography.

Participants

The included patients visited the University Clinic of Cardiology at Innsbruck (Austria), which fulfils a secondary and tertiary hospital function. Inclusion took place in the period between February 2004 and April 2008 and resulted in a total of 8296 patients aged 18–91 years; 65% of them were men.

Findings to date

There was one follow-up round on vital status through record linkage for 84% of the cohort (those with residence in Tyrol), resulting in a follow-up duration of over 5.5 to nearly 10.0 years among survivors. The data contain basic patient characteristics, cardiovascular risk factors, laboratory measurements, medications, detailed information on the extent and severity of coronary artery disease, revascularisation history, treatment strategy and mortality specifics. A few studies have already been published.

Future plans

Various diagnostic and prognostic studies are planned, also concerning complications, competing risks and cost-effectiveness. Collaboration with other research groups is welcomed.

Keywords: coronary artery disease, elective cardiac catheterisation, cardiovascular risk factors, clinical epidemiology, cohort study

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This large consecutive Coronary Artery disease Risk Determination In Innsbruck by diaGnostic ANgiography (CARDIIGAN) patient group has good and detailed data, especially on coronary arteries and past interventions; thus, it is possible to address many relevant clinical research questions.

Several possible sources of selection bias are ruled out through elective ‘all-comer’ recruitment in routine practice.

There are no data on non-invasive diagnostic results before inclusion in the cohort and no storage of serum and urine.

This is a single-centre cohort, so external validity can be questionable with certain topics.

Some data are missing due to limited resources during daily routine.

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases are prevalent worldwide, and is the leading cause of death both in men and women in Austria.1 2 Particularly for coronary artery disease (CAD), up to now research into the determinants, such as the Framingham Heart Study, has focused mainly on aetiology and prognosis,3 and only few studies pertain to the predictors of diagnosis or severity of angiographically ascertained CAD in larger cohorts.

Originally the cohort was implemented as a screening programme to attain more insights into the set of risk factors and their relation to and their predictive value to the diagnosis and severity of CAD of consecutive patients referred for elective cardiac catheterisation to the Department of Cardiology at the University Hospital of Innsbruck, Austria. An additional aim was quality inspection on risk factor control and therapeutic strategies. Additionally, the programme enables comparison of the patients in the referral area of our hospital with those of other studies and registries, thereby optimising the risk management of our patients. A few years ago, retrospectively more information on coronary arteries was extracted and survival information from the regional social security registry was linked,4 thereby finally establishing the Coronary Artery disease Risk Determination In Innsbruck by diaGnostic ANgiography (CARDIIGAN) cohort. It was then that the potential of this cohort was fully recognised and research questions were further worked out, starting with the diagnostic ones.

Cohort description

Initial patient inclusion was between February 2004 and April 2008, resulting in a total of 8296 consecutive patients of 18 years and older electively referred for invasive evaluation of a suspected CAD. After informed consent was obtained, they received conventional coronary angiography (CA) by the standard Judkins technique, predominantly via the femoral approach. The participation of a patient did not lead to any excess risks. Blood chemistry was done in the context of daily clinical routine, as was the execution of the study itself.

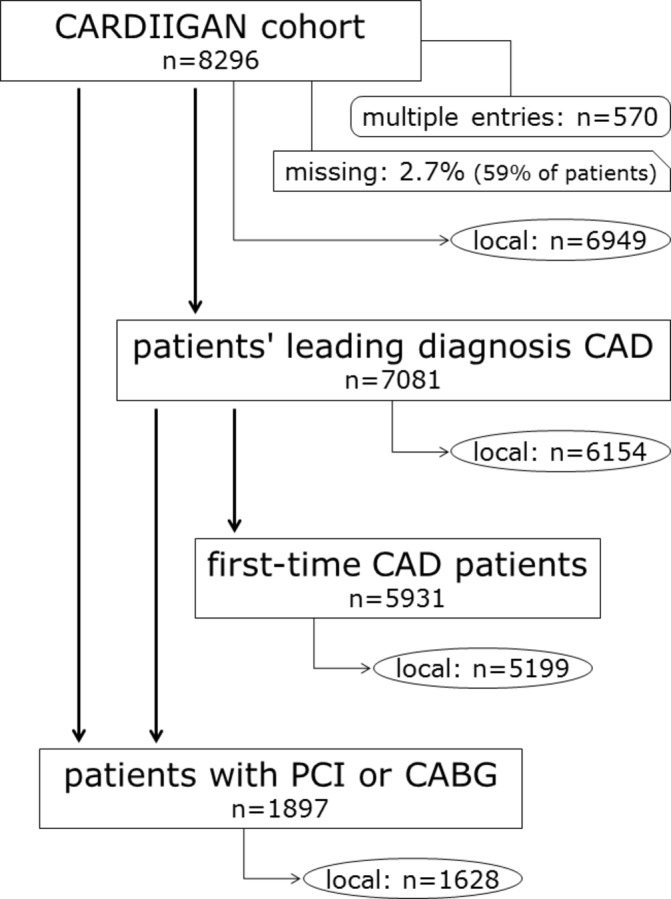

The cohort was 65% male and on average 63 years of age (between 18 and 91 years). A part of the cohort consists of patients with history of coronary revascularisation (percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass grafting). This subgroup with 1897 persons has a higher male proportion of 75% with similar age (average of 64 years, between 28 and 91 years). Another, partly overlapping subgroup of CARDIIGAN has CAD as the leading diagnosis (n=7081), at the exclusion of those referred for cardiac catheterisation due to a specific extracardiac condition (eg, solid organ transplantation) or cardiac disease other than CAD (such as heart transplantation or valvular and congenital heart disease). Of these patients with CAD, 5931 (84%) presented for the first time with this diagnosis. Since the University Clinic Innsbruck serves as a secondary as well as a tertiary hospital, a portion of the cohort members came from outside the primary catchment area (thereof nearly a quarter from abroad) of the regional social security service of Tyrol. This regional system is the source of the data on vital status. Thus these data are available for about 84% of the patients, the so-called ‘local’ patient group (figure 1). Many of the other 16% of patients are typical of the tourism in this region and would probably often be incomparable with patients of cardiology clinics elsewhere.

Figure 1.

Subgroups of the CARDIIGAN cohort. The term ‘local’ indicates that survival data are available from the regional social security system. CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CAD, coronary artery disease; CARDIIGAN, Coronary Artery disease Risk Determination In Innsbruck by diaGnostic ANgiography; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Most data entry was done shortly after the patient was presented to the clinic. A part of the information (detailed laboratory data) was extracted from patients’ charts after discharge and another part (final CA report) retrospectively, when the large potential of the cohort was realised and more details on the arteries deemed invaluable for relevant research questions. Also, a first record linkage was performed to assess survival status, with the date and cause of death, of the ‘local’ part of the CARDIIGAN cohort. Thereby there is information on survival of the highest possible quality,5 6 available up to 1 January 2014, resulting in over 5 years of follow-up per person. During the first 5 years 13% had died. More linkage is now planned to update information on survival status, but also to assess the status of other events. Particularly data on various cardiovascular disease outcomes are to be gathered to enable appraisal of subsequent manifestations of arterial diseases.

Since the data documentation had to fit into the daily routine with limited time resources, some entries were incomplete and thereby a part of the data are missing. Of the clinical data 2.7% were lost, which concerns some 59% of the 8296 patients. As for the medication information, the documentation occurred suboptimally and so 47% was missing. The problem of missing values will be handled by applying multiple imputation techniques.7 8

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the included patients, and basic data include residence, sex, age, height, weight and smoking status. Also symptoms of angina pectoris according to the so-called Canadian Cardiovascular Society score,9 hypertension (<140/90 mm Hg or relevant medication10), diabetes mellitus (fasting plasma glucose ≥126 mg/dL or medication11) and family history of premature myocardial infarction (first degree: male relative at age <55 years, female relative at age <65 years12) have been documented, as well as seven types of medication (antianginal, antihypertensive and lipid-lowering). On the laboratory parameters, there are 15 different parameters, including lipids. Detailed information on the three major coronary arteries and their main side branches, including the extent and severity of atherosclerotic obstructions and prior or current interventions, is available. Stenoses of the arteries were categorised into 0%, less than 50%, 50%–70% and over 70% obstruction. This enables categorisation of CAD into none, non-obstructive, and one-vessel, two-vessel or three-vessel disease. Other outcome measures are proposed treatment and survival status as of 31 December 2013, with date and cause of death.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the cohort participants in CARDIIGAN (n=8296)

| Characteristics | Specifics | Missing (n) |

| Sex | Female: 2908 (35%) Male: 5388 (65%) |

0 |

| Age at baseline (years), mean (SD) |

63 (11) | 0 |

| Residence | Tyrol: 6949 (84%) Rest of Austria: 1027 (12%) Foreign: 320 (4%) |

0 |

| Height (m), mean (SD) |

1.71 (0.09) | 117 |

| Weight (kg), mean (SD) |

78.4 (14.9) | 118 |

| Smoking status | Never: 3660 (52%) Former: 1929 (27%) Current: 1495 (21%) |

1212 |

| Angina pectoris complaints | None: 3671 (44%) Stable: 2986 (36%) Unstable: 1269 (15%) Atypical: 370 (4%) |

0 |

| Myocardial infarction | None: 6523 (79%) STEMI: 459 (6%) NSTEMI: 631 (8%) MCI: 683 (8%) |

0 |

| Valvular/congenital heart disease | No: 6395 (87%) Yes: 957 (13%) |

944 |

| Cardiomyopathy | No: 3793 (86%) Yes: 594 (14%) |

3909 |

| Solid organ transplantation | No: 8128 (98%) Yes: 168 (2%) |

0 |

| Hypertension | No: 2227 (27%) Yes: 6069 (73%) |

0 |

| Diabetes mellitus | No: 6902 (83%) Yes: 1394 (17%) |

0 |

| Family history of myocardial infarction (first-degree relative: male <55 years; female <65 years) |

No: 6532 (79%) Yes: 1764 (21%) |

0 |

| Lipid-lowering medication: statin | No: 2521 (46%) Yes: 2967 (54%) |

2808 |

| Antihypertension/anti-anginal medication |

No: 1141 (20%) Yes: 4434 (80%) |

2721 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL), mean (SD) | 193 (45) | 585 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL), mean (SD) | 54.9 (17.0) | 741 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL), mean (SD) |

123 (38) | 756 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL), median (IQR) |

126 (91–175) | 591 |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL), median (IQR) |

367 (297–459) | 265 |

| C reactive protein (mg/dL), median (IQR) |

0.28 (0.12–0.70) | 207 |

| Prothrombin time (%), mean (SD) | 103 (13) | 151 |

| Thrombocytes (×1000 U/µL), mean (SD) | 233 (67) | 147 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL), mean (SD) | 14.3 (2.3) | 119 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL), mean (SD) | 1.07 (0.72) | 105 |

| Gamma-glutamyltransferase (U/L), median (IQR) |

33 (21–54) | 321 |

| Uric acid (mg/dL), mean (SD) | 6.33 (1.76) | 970 |

| Urea (mg/dL), median (IQR) | 35.4 (29.1–44.4) | 248 |

| Maximum degree of stenosis | None: 2029 (25%) <50%: 1588 (20%) ≥50%–70%: 296 (4%) ≥70%: 4157 (52%) |

226 |

| Number of stents | None: 5918 (76%) 1: 1398 (18%) ≥2: 424 (5%) |

556 |

| Number of bypass | None: 7330 (94%) ≥1: 439 (6%) |

527 |

| Cause of death (up until 31 December 2013) with complete ICD-10 code | Alive: 5366 (77%) Cardiovascular death: 746 (11%) Other causes: 837 (12%) |

1347 |

CARDIIGAN, Coronary Artery disease Risk Determination In Innsbruck by diaGnostic ANgiography; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases, tenth revision; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; MCI, myocardial infarction; NSDTEMI, non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in the development and design of the project.

Findings to date

In a first publication, even before the end of the inclusion period, the results on the association of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol and C reactive protein in relation to angiographically evaluated CAD were presented and showed that the two biomarkers seem to have an important independent association with the prevalence of the disease (table 2).13 More recently, a small study was done focusing on sex differences concerning CAD and cardiovascular risk factors: especially the impact of smoking and hypercholesterolaemia seems to differ between men and women.14

Table 2.

Extract of the multivariable results from Alber et al 13

| All patients | CAD vs non-CAD | Wald statistic | |

| OR | 95% CI | ||

| Age (per year) | 1.058 | 1.051 to 1.066 | 247.7 |

| Male gender | 2.753 | 2.371 to 3.197 | 175.9 |

| HDL cholesterol (per mg/dL) | 0.976 | 0.971 to 0.982 | 77.3 |

| Prior statin use | 1.751 | 1.511 to 2.029 | 55.3 |

| Smokers | 1.720 | 1.396 to 2.118 | 25.9 |

| Hypertension | 1.494 | 1.244 to 1.793 | 18.5 |

| Diabetes | 1.539 | 1.250 to 1.894 | 16.5 |

| C reactive protein (per log unit) | 1.343 | 1.158 to 1.558 | 15.1 |

| Total cholesterol (per mg/dL) | 1.003 | 1.001 to 1.005 | 9.2 |

| Triglycerides (per log unit) | 0.917 | 0.621 to 1.355 | 0.2 |

Reproduced with permission from the European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2008. The Authors. Journal Compilation 2008 Blackwell Publishing.

CAD, coronary artery disease; HDL, high-density lipoprotein.

After completion of patient recruitment and data management processes (including survival data linkage), the focus was on diagnostic prediction modelling. An interim study was presented at a meeting of the Austrian Society of Cardiology15 and recently a full manuscript was published16: validation of an existing CAD diagnosis model showed moderate performance, but extension with HDL and LDL cholesterol, fibrinogen and C reactive protein led to a relevant extra net benefit. After this study a more refined polytomous regression analysis was done to predict five ordinal categories of CAD diagnosis, thus enabling a better treatment decision and possibly making some future angiographies unnecessary (accepted publication in Int J Cardiol 2018 doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.05.092).17 18 Currently we are analysing data on chronic kidney disease to assess the associations of this disease, severity of CAD and mortality as inspired by the work of Brand et al 19 and our own previous work.20 Other ideas involve complications,21 in particular bleedings,22 competing risks in mortality23–26 and cost-effectiveness,27 28 especially in the context of prioritisation of vascularisation.29 30

Strengths and limitations

It is unfortunate that survival assessment is not possible for the complete cohort; it is restricted to 84% of the participants. Actually it only involves those people who are residents of Tyrol, so the results apply to a clearly defined group and generalisability is probably not compromised in this respect. Another weakness is the absence of a personal follow-up of patients due to limited available resources at discharge. However, a very good alternative is the feasible and proven record linkage option. It is also unfortunate that there is a lack of information on non-invasive diagnostic modalities and results, since these might be relevant in the diagnostic work-up. This, and other aspects of the healthcare system, might lead to some selective referral bias, and one must be careful when interpreting the results. On the other hand, possible selection is counteracted because of the patients being assigned to a wide range of doctors, that is, general practitioners, internists and cardiologists. Ideally, research possibilities would have been enhanced if serum and urine could have been stored at the time to enable future additional laboratory tests, making it possible to include various novel biomarkers currently being introduced in this field.31 Furthermore, we are inevitably confronted with missing information since the daily routine did not always allow complete registration of data; however, there are statistical imputation techniques to compensate for this limitation.

As for the strengths, this consecutive patient group comprises a large clinical cohort with 5–10 years of follow-up, with good and detailed data. The study involves an elective ‘all-comer’ recruitment, which excludes some potential sources of selection bias. Also, the study represents routine practice and therefore allows the assessment of the effectiveness of certain procedures, as opposed to the ideal case scenarios. Particularly valuable are the data on various routine laboratory results and extensive information on the arteries and past interventions.

Collaboration

Cooperation with other researchers is very much favoured. A contact has already been established with a local neurological research group. Furthermore, international participation is being searched for with experts in various fields. Particularly Ewout Steyerberg, professor of clinical biostatistics and medical decision making and one of the leading scientists in clinical prediction models,32 has been welcomed to theoretically strengthen our research group. Also, Ben van Calster has been involved for his expertise on multinomial risk models.33 Collaboration with other research groups with comparable data to enable external validation studies would be beneficial to further the prediction modelling plans. For more information the corresponding author (ME) can be contacted (Michael.Edlinger@i-med.ac.at).

Acknowledgments

We thank all the patients for their commitment and all personnel who helped in some way or another.

Footnotes

Contributors: HFA, JD and MW initiated the project and coordinated the data entry. MW extracted extra detailed data on the coronary arteries. ME was responsible for data management and preparation. MW wrote the manuscript. HFA is the PI of the CARDIIGAN cohort. HFA, JD and ME revised the manuscript critically. All authors are accountable for this work.

Funding: CARDIIGAN is an investigator-initiated cohort and no funding was received.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Approval was obtained, for both the original study group and the extension to a cohort with ascertained survival status, from the ethical committee of the Medical University of Innsbruck (UN3266 and AN3266).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Collaboration is welcomed and data sharing can be agreed upon. The corresponding author can be contacted.

References

- 1. WHO. Health statistics and information systems. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/estimates/en/index1.html (accessed 14 Oct 2016).

- 2. Statistics Austria. Todesursachen gesamt. http://www.statistik.at/web_de/statistiken/menschen_und_gesellschaft/gesundheit/todesursachen/todesursachen_im_ueberblick/index.html (accessed 14 Oct 2016).

- 3. Chen G, Levy D. Contributions of the Framingham Heart Study to the epidemiology of coronary heart disease. JAMA Cardiol 2016;1:825–30. 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.2050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Oberaigner W, Stühlinger W. Record linkage in the cancer registry of Tyrol, Austria. Methods Inf Med 2005;44:626–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Oberaigner W. Errors in survival rates caused by routinely used deterministic record linkage methods. Methods Inf Med 2007;46:420–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Oberaigner W, Siebert U. Are survival rates for Tyrol published in the Eurocare studies biased? Acta Oncol 2009;48:984–91. 10.1080/02841860903188635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Moons KG, Donders RA, Stijnen T, et al. . Using the outcome for imputation of missing predictor values was preferred. J Clin Epidemiol 2006;59:1092–101. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Li P, Stuart EA, Allison DB. Multiple imputation: a flexible tool for handling missing data. JAMA 2015;314:1966–7. 10.1001/jama.2015.15281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Campeau L. The Canadian Cardiovascular Society grading of angina pectoris revisited 30 years later. Can J Cardiol 2002;18:371–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. . The seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA 2003;289:2560–72. 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2008;31(Suppl 1):S55–S60. 10.2337/dc08-S055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mancia G, de Backer G, Dominiczak A, et al. . Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2007;2007:1462–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Alber HF, Wanitschek MM, de Waha S, et al. . High-density lipoprotein cholesterol, C-reactive protein, and prevalence and severity of coronary artery disease in 5641 consecutive patients undergoing coronary angiography. Eur J Clin Invest 2008;38:372–80. 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2008.01954.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Suessenbacher A, Wanitschek M, Dörler J, et al. . Sex differences in independent factors associated with coronary artery disease. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2014;126:718–26. 10.1007/s00508-014-0602-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wanitschek M, Edlinger M, Dörler J, et al. . Performance of a simple five-variable score model for the prediction of invasively evaluated significant coronary artery disease among elective patients. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2013;125(Suppl 1):s76. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Edlinger M, Wanitschek M, Dörler J, et al. . External validation and extension of a diagnostic model for obstructive coronary artery disease: a cross-sectional predictive evaluation in 4888 patients of the Austrian Coronary Artery disease Risk Determination In Innsbruck by diaGnostic ANgiography (CARDIIGAN) cohort. BMJ Open 2017;7:e014467 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Biesheuvel CJ, Vergouwe Y, Steyerberg EW, et al. . Polytomous logistic regression analysis could be applied more often in diagnostic research. J Clin Epidemiol 2008;61:125–34. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Van Hoorde K, Vergouwe Y, Timmerman D, et al. . Assessing calibration of multinomial risk prediction models. Stat Med 2014;33:2585–96. 10.1002/sim.6114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Brand E, Pavenstädt H, Schmieder RE, et al. . The Coronary Artery Disease and Renal Failure (CAD-REF) registry: trial design, methods, and aims. Am Heart J 2013;166:449–56. 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wanitschek M, Pfisterer M, Hvelplund A, et al. . Long-term benefits and risks of drug-eluting compared to bare-metal stents in patients with versus without chronic kidney disease. Int J Cardiol 2013;168:2381–8. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.01.257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jeschke E, Baberg HT, Dirschedl P, et al. . [Complication rates and secondary interventions after coronary procedures in clinical routine: 1-year follow-up based on routine data of a German health insurance company]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 2013;138:570–5. 10.1055/s-0032-1333012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Doktorova M, Motovska Z. Clinical review: bleeding - a notable complication of treatment in patients with acute coronary syndromes: incidence, predictors, classification, impact on prognosis, and management. Crit Care 2013;17:239 10.1186/cc12764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hemingway H, Croft P, Perel P, et al. . Prognosis research strategy (PROGRESS) 1: a framework for researching clinical outcomes. BMJ 2013;346:e5595 10.1136/bmj.e5595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Möhlenkamp S, Lehmann N, Moebus S, et al. . Quantification of coronary atherosclerosis and inflammation to predict coronary events and all-cause mortality. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:1455–64. 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.10.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Andersen PK, Geskus RB, de Witte T, et al. . Competing risks in epidemiology: possibilities and pitfalls. Int J Epidemiol 2012;41:861–70. 10.1093/ije/dyr213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lau B, Cole SR, Gange SJ. Competing risk regression models for epidemiologic data. Am J Epidemiol 2009;170:244–56. 10.1093/aje/kwp107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Patel MR, Peterson ED, Dai D, et al. . Low diagnostic yield of elective coronary angiography. N Engl J Med 2010;362:886–95. 10.1056/NEJMoa0907272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hunink MGM, Glasziou PP, Siegel JE, et al. ; Decision Making in Health and Medicine; Integrating Evidence and Value. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hemingway H, Henriksson M, Chen R, et al. . The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of biomarkers for the prioritisation of patients awaiting coronary revascularisation: a systematic review and decision model. Health Technol Assess 2010;14:1–151. 10.3310/hta14090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Henriksson M, Palmer S, Chen R, et al. . Assessing the cost effectiveness of using prognostic biomarkers with decision models: case study in prioritising patients waiting for coronary artery surgery. BMJ 2010;340:b5606 10.1136/bmj.b5606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McCarthy CP, McEvoy JW, Januzzi JL. Biomarkers in stable coronary artery disease. Am Heart J 2018;196:82–96. 10.1016/j.ahj.2017.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Steyerberg EW. Clinical Prediction Models; a Practical Approach to Development, Validation, and Updating. New York: Springer, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Van Calster B, Van Hoorde K, Valentin L, et al. . Evaluating the risk of ovarian cancer before surgery using the ADNEX model to differentiate between benign, borderline, early and advanced stage invasive, and secondary metastatic tumours: prospective multicentre diagnostic study. BMJ 2014;349:g5920 10.1136/bmj.g5920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]