Abstract

Objectives

The study aimed tocompare recurring themes in the artistic expression of military service members (SMs) with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), traumatic brain injury and psychological health (PH) conditions with measurable psychiatric diagnoses. Affective symptoms and struggles related to verbally expressing information can limit communication in individuals with symptoms of PTSD and deployment-related health conditions. Visual self-expression through art therapy is an alternative way for SMs with PTSD and other PH conditions to communicate their lived experiences. This study offers the first systematic examination of the associations between visual self-expression and standardised clinical self-report measures.

Design

Observational study of correlations between clinical symptoms of post-traumatic stress, depression and anxiety and visual themes in mask imagery.

Setting

The National Intrepid Center of Excellence at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Maryland, USA.

Participants

Active-duty military SMs (n=370) with a history of traumatic brain injury, post-traumatic stress symptoms and related PH conditions.

Intervention

The masks used for analysis were created by the SMs during art therapy sessions in week 1 of a 4-week integrative treatment programme.

Primary outcomes

Associations between scores on the PTSD Checklist–Military, Patient Health Questionnaire-9 and Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale on visual themes in depictions of aspects of individual identity (psychological injury, military symbols, military identity and visual metaphors).

Results

Visual and clinical data comparisons indicate that SMs who depicted psychological injury had higher scores for post-traumatic stress and depression. The depiction of military unit identity, nature metaphors, sociocultural metaphors, and cultural and historical characters was associated with lower post-traumatic stress, depression and anxiety scores. Colour-related symbolism and fragmented military symbols were associated with higher anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress scores.

Conclusions

Emergent patterns of resilience and risk embedded in the use of images created by the participants could provide valuable information for patients, clinicians and caregivers.

Keywords: traumatic brain injury, post traumatic stress, military, visual imagery, depression, anxiety

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study offers the first systematic examination of the associations between visual self-expression and how it relates to standardised clinical self-report measures.

This is the first study to demonstrate patterns of risk and resilience as they relate to visual imagery created by military service members with traumatic brain injury and symptoms of post-traumatic stress.

The visual imagery was created in art therapy sessions and cannot be applied to other contexts of art making.

The study was performed within the framework of a comprehensive integrative outpatient assessment and treatment programme.

The findings are associative and correlational in nature, which precludes attribution of any causal relationships.

The study findings are limited to men and women actively serving in the US military.

Introduction

Since 2001, more than 2.7 million servicemen and servicewomen have been deployed in support of combat operations around the world.1 A survey conducted by the Veterans Administration from 2006 to 2010 estimated that post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has affected about 480 748 service members (SMs).1 Additionally, 379 5192 military SMs were diagnosed as having suffered a traumatic brain injury (TBI), the vast majority of them in the mild range.3 Recent research has highlighted the co-occurrence of these severe diagnoses in military SMs, with the total financial costs of treating these disorders estimated as high as $6 billion for those with PTSD and $910 million for those with TBI.4 Effective care for those with persistent neurological and behavioural symptoms from these injuries is imperative, both for the society and for the military health system. PTSD and TBI are conditions that are particularly prevalent among veterans.3 5 Individually complex, the effects of these conditions are exacerbated when they occur together.6 Because the neuroanatomical disturbances and the symptoms of PTSD and TBI may be similar, it is possible that they share some common mechanisms.6 Individuals with TBI often develop PTSD and experience psychological health (PH) symptoms such as irritability, anger, heightened arousal, lack of concentration and sleeping difficulties.7 Psychological disorders such as depression and anxiety have also been found to be common comorbid conditions in individuals with PTSD and TBI.8 9 In addition, demographic characteristics like time in the service, including multiple deployments,10–13 race/ethnicity,14 15 and rank (officer or enlisted SM)16 17 have been associated with severity of symptoms.

One of the challenges with treating PTSD can be the limited ability of the patient to express his or her symptoms verbally.18–20 Thus alternative forms of communication such as visual self-expression through art therapy are increasingly accepted as treatments for individuals with PTSD, TBI and PH.21–26 Mask-making is one such art therapy approach that has shown significant promise.27–29 Specifically, ‘trauma masks’ have assisted military SMs to visually communicate the effects of combat-related trauma to help build a coherent sense of self postinjury.30–32 Through the use of symbols and sensations that are externalised and shaped into a narrative, art therapy can assist in the processing of traumatic material,30 making the traumatic material more tolerable through its externalisation, and enable narrative construction of fragmented trauma memories.25 32–35 Art therapy is a particularly useful approach for symptoms of combat-related PTSD, such as avoidance and emotional numbing, while also attending to underlying issues for this population, including relaxation, non-verbal expression, containment, symbolic expression, externalisation and pleasure.24 25

Although cognitive processing therapy is the first line of psychotherapy in the military,36 other approaches like art therapy have been shown to decrease anxiety in adults with a variety of mental health conditions.37–41 Results from the combination of cognitive behavioural therapy and art therapy indicate that art therapy could be a viable addition, particularly for patients with panic disorder with agoraphobia and generalised anxiety disorder who are not responsive to verbal therapies.41 By creating visible depictions of their internal psychological states in art therapy sessions, patients have the opportunity to observe a tangible externalised object. This process and the resulting image may aid them in developing strategies to cope with feared situations, thereby desensitising them to the fear at hand38 41 and helping them to engage their senses to foster a connection between the mind and the body.42 Similarly, art therapy has been found to reduce depressive symptoms35 through evoking the expression of positive emotions through the creative process, building social connections43 and providing an alternative form of self-expression.44

Most of the findings in art therapy and the military have tended to be based on clinical observations and small pilot studies.24 25 Despite clinical reports of the potential of art therapy to address symptoms of depression and anxiety, no one has examined the associations between the imagery created in art therapy sessions with standardised measures of clinical symptoms. Analysis of SMs’ visual representations in masks indicates that they depict a range of experiences related to PTSD and TBI, including the use of visual metaphors, depictions of psychological injuries and reflections on the experiences of belonging in the military and deployment in a war zone. We present the associations between themes in the mask imagery made during art therapy sessions and corresponding measures of depression, anxiety and PTSD.26

Methods

Setting

The National Intrepid Center of Excellence (NICoE) located at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (Bethesda, Maryland, USA) offers an interdisciplinary intensive outpatient programme that uses an integrative holistic model of care to serve active-duty SMs with a history of TBI, a comorbid PH condition and symptoms that have not responded to first-line treatments. On referral and acceptance, six new SMs and their families, as available, are admitted to the centre each Monday and move through the 4-week programme as a therapeutic cohort. SMs undergo a standardised evaluation using core assessment tools, which includes contact with 17 medical and integrative health disciplines. As part of the initial behavioural health assessment and treatment, all SMs engage in a group art therapy mask-making session in week 1 of their 4-week integrative treatment programme. A series of neurological, psychiatric and psychological assessments are conducted concurrently with the art therapy sessions. The intake surveys are completed in the same week as the mask-making (week 1), but prior to the mask-making session as part of a battery of intake assessments on admission.

The authors obtained the consent of the SMs to use all of their clinical data for research purposes.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public did not participate in the research design or data analysis for this study.

Participants

Participants in the study included SMs (n=370). They ranged in age from 20 to 50 years and included SMs from all branches of the Armed Services, including the National Guard, who were referred to the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (NICoE intensive outpatient treatment programme). These individuals had a history of mild TBI and comorbid PH concerns, including mood problems, stress symptoms (or overt PTSD) or other related conditions.

Data sources

All data at the NICoE are archived in a specialised de-identified database that can link mask images, participants’ narrative descriptions of mask imagery, experiences in art therapy as described in the clinical notes of the therapists and standardised measures of psychological functioning. In a previous publication, we described the process of identifying thematic classifications in the mask-making products created by SMs.26 Figures 1–8 describe the prominent themes in the masks used for analysis and a sample image visually depicting those themes. (Artwork credit: NICoE and Veterans Affairs National Center for Ethics in Health Care.) The thematic classifications generated from this analysis were converted into a database that included dichotomous variables (1=theme present and 0=theme absent). Thus, each SM’s mask included a 0 or 1 for each classification that was identified for the whole data set. The data were coded by four members of the research team. Two of the coders coded all the data and then two more coders checked these codes. Discrepancies in coding were reviewed, and a final code was assigned as apt in consultation with the lead author. Masks were coded for more than one thematic category if more than one was represented in the image. Every mask had more than one theme associated with the imagery and all of the themes were included in the analysis. Additional details on the coding process are described in a previous publication.26 Given that some of the themes recurred many times and others only a few times, we chose a cut-off of n=20 for the classifications to be included in the database in order to have an adequate number for analyses. The coded database was then integrated with the standardised data from the PTSD Checklist-Military (PCL-M),45 the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)46 and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7)47 scale for further analysis. These questionnaires were administered to the SMs during the same week as the mask-making art therapy sessions. Although the data were collected at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, the de-identified data set was transferred to Drexel for analysis, per prior agreement. No coded linkage information was kept at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center.

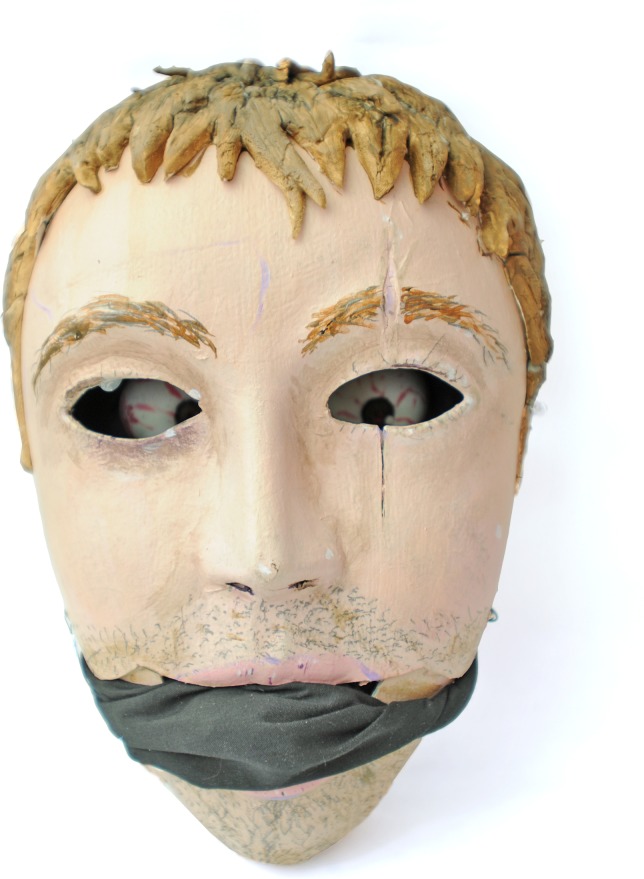

Figure 1.

Psychological injury (depiction of psychological struggles with sadness, anger, inability to verbalise and social isolation).

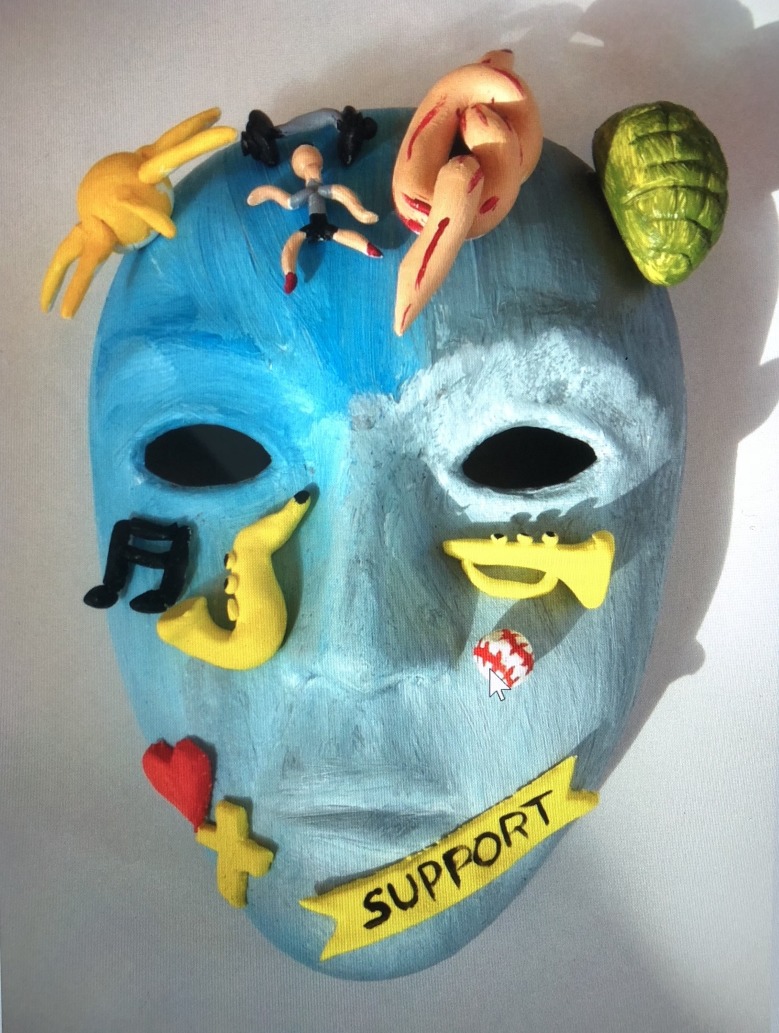

Figure 2.

Identification with military unit (depiction of sense of belonging to a military unit, for example, explosive ordnance disposal badge, also known as the ‘crab’).

Figure 3.

Use of fragmented military symbols (depiction of fragmented symbols associated with the military such as flags, camouflage fabric and dog tags).

Figure 4.

Metaphors (depiction of inner psychological states through a visual image).

Figure 5.

Colour symbolism (specific individual colours as metaphorical representations of experiences and emotions).

Figure 6.

Cultural or historical characters (depiction of characters from history, films and literature).

Figure 7.

Sociocultural symbols (inclusion of images from objects commonly seen in society).

Figure 8.

Nature images (inclusions of images from nature in mask).

Data analysis

The data were first summarised using descriptive statistics of study variables. For subsequent analyses, we focused especially on the most frequently occurring elements represented in the masks.26 Using the unique ID number provided for each SM, we ran independent sample t-tests to examine whether the mean scores for post-traumatic stress symptoms as measured by the PCL-M, for depressive symptoms as measured by the PHQ-9 and for anxiety symptoms as measured by the GAD-7 differed depending on whether the participants’ themes were psychological injury, military identity or metaphors. Finally, we explored the metaphor themes further by conducting analysis of covariance tests to examine the unique effects of the different uses of metaphors on the symptom scales. Given that metaphors were represented in four different ways, we wanted to examine if the type of visual metaphor would be associated with symptoms of post-traumatic stress, depression and anxiety.

Results

Overall, based on clinical notes maintained by the art therapist, when referring to the experience of making the masks, SM participants reported that art therapy helped mainly with enjoyment (n=136), with focus and concentration (n=72) and with relaxation/calming (n=52). In addition, SMs (n=74) said the mask-making helped with socialisation and with opening up about their injuries, treatment processes and struggles. A small proportion of participants (n=11) did not report a positive experience and cited reasons like dissatisfaction with the final product and disinterest in art making. Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for the study variables.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for demographics and clinical study variables

| n | % of sample | |

| Male | 361 | 97.0 |

| African–American | 14 | 3.8 |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 8 | 2.2 |

| Caucasian | 329 | 89.2 |

| Hispanic | 15 | 4.1 |

| Air Force | 33 | 8.9 |

| Army | 119 | 32.2 |

| Coast Guard | 1 | 0.3 |

| Marines | 50 | 13.5 |

| Navy | 167 | 45.1 |

| Officer | 54 | 14.6 |

| M | SD | |

| Age, years | 36.08 | 7.62 |

| Time in service, years | 14.61 | 7.31 |

| PCL-M score | 51.98 | 15.86 |

| PHQ-9 score | 13.10 | 6.17 |

| GAD-7 score | 10.65 | 6.01 |

GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale; PCL-M, PTSD Checklist for DSM-5; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

Table 2 shows differences in mean symptoms for the mask themes of ‘psychological injury’ and ‘metaphors’. Participants whose masks reflected evidence of psychological injury (n=102) in the mask-making reported higher PTSD symptoms, whereas those whose masks coded positive for metaphors (n=125) had lower anxiety symptoms. Those who used symbols that included fragmented representations of military symbols (n=44) reported more anxiety, whereas those who used representations of their military unit identity (n=41) reported less PTSD and depression. Fragmented refers here to pieces of items associated with the military such as camouflage fabric and pieces of weapons, flags and tags. Table 3 provides three univariate analyses of covariance used to determine whether there were mean differences in the subtypes of the broad theme of metaphors while controlling for time in the service, race/ethnicity and officer status. These covariates were chosen as controls based on the literature in order to account for any effects that might be related to these demographic variables. As shown, participants whose masks showed evidence of colour symbolism (use of colour as a metaphor) (n=46) had higher PCL-M and PHQ-9 scores. Participants whose masks showed evidence of cultural/historical characters (n=21) and cultural/societal symbols (n=42) had lower GAD-7 scores and tended to have lower depressive symptom scores. In addition, the use of nature-related imagery (n=33) trended towards lower post-traumatic stress symptom scores, indicating the potential health-promoting aspect when SMs depicted such imagery.

Table 2.

Mean and SD for the symptom scores across mask classifications

| Outcome | Psychological injury | Metaphors | ||||

| No | Yes | t | No | Yes | t | |

| PCL-M (n=349) | 50.66 (16.26) | 55.51 (14.24) | −2.72** | 52.06 (15.94) | 51.83 (15.78) | 0.132 |

| PHQ-9 (n=282) | 12.95 (6.16) | 13.54 (6.22) | −0.710 | 13.25 (6.23) | 12.84 (6.09) | 0.530 |

| GAD-7 (n=75) | 9.96 (5.74) | 12.83 (6.47) | −1.79 | 11.96 (6.05) | 8.46 (5.36) | 2.52* |

| Outcome | Military symbols | Identification with military unit | ||||

| No | Yes | t | No | Yes | t | |

| PCL-M (n=349) | 51.51 (16.05) | 55.54 (14.07) | 1.53 | 52.59 (15.73) | 42.52 (15.33) | 2.847** |

| PHQ-9 (n=282) | 13.03 (6.26) | 13.72 (5.41) | −0.572 | 13.3 (6.10) | 9.75 (6.57) | 2.255* |

| GAD-7 (n=75) | 10.23 (5.87) | 18.25 (2.22) | −6.128** | 10.93 (6.01) | 6.80 (5.07) | 1.497 |

*P<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.1.

GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale; PCL-M, PTSD Checklist for DSM-5; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

Table 3.

Mean differences in symptom scores for those whose masks showed evidence of metaphor subtypes

| Variable (% coded positive) | PCL-M (η2 =0.23) | sη2 | PHQ-9 (η2 =0.28) | sη2 | GAD-7 (η2 =0.50) | sη2 | ||||||

| No | Yes | F(1, 306) | No | Yes | F(1, 245) | No | Yes | F(1, 54) | ||||

| Colour symbolism (12.2%) | 51.14 | 58.34 | 8.23** | 0.03 | 13.92 | 16.96 | 7.18** | 0.03 | 10.08 | 9.22 | 0.07 | 0.002 |

| Cultural/historical characters (5.7%) | 55.71 | 53.78 | 0.27 | 0.001 | 16.80 | 14.07 | 3.53*** | 0.02 | 13.10 | 6.20 | 9.19** | 0.20 |

| Sociocultural symbols (11.4%) | 56.08 | 53.41 | 0.88 | 0.001 | 16.33 | 14.54 | 2.09 | 0.003 | 13.22 | 6.08 | 6.57* | 0.15 |

| Nature metaphors (8.9%) | 57.46 | 52.03 | 3.38*** | 0.01 | 16.11 | 14.77 | 1.23 | 0.003 | 10.53 | 8.76 | 0.92 | 0.01 |

All three analyses of covariance tests were controlled for time in service, ethnicity and officer status.

*P<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.1

GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale; PCL-M, PTSD Checklist for DSM-5; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

Discussion

This study examined participants’ experiences of art therapy and associations between the visual imagery in the masks and clinical data from standardised measures of symptoms of post-traumatic stress, depression and anxiety. The findings indicate that there are patterns of recurring associations between clinical symptoms in the visual imagery created by SMs in art therapy sessions. Some of the specific findings of note are that participants whose masks depicted psychological injury reported higher scores on the PCL-M scale. This finding indicates a potential clinical significance when SMs depict their psychological injuries and that this could be helpful to direct specific focus on the clinical care of PTS symptoms when such imagery is depicted, such that depiction of psychological struggles might be an indicator of heightened symptoms of post-traumatic stress requiring targeted care. When we reviewed artwork of combat veterans with PTSD, we found evidence of ‘post-traumatic conflict being experienced and depicted by the graphic themes of war and the telling of self-portraits of disfigurement symbolic of alteration of one’s previous self’ (p44).30 SMs might be less likely to report mental health issues due to the social stigma that these issues may be misinterpreted as weakness or laziness.48–51 The association between post-traumatic stress scores and visual depiction of psychological injury suggests that this might be a forum for safe self-expression.

Those participants whose masks coded positive for metaphors also reported lower anxiety symptoms, indicating that the use of metaphors is associated with the SM reaching a level of insight into the psychological issues in order to lower the level of anxiety and perhaps develop some inner resilience that enables the SM to depict images that involved imaginative variations on the lived psychological experience. Further examination of subtypes of metaphors revealed potential differences in the associations with clinical data. For example, the use of colour symbolism (eg, when an SM said that the colour represented something specific like red represented victory or blue represented sadness) was associated with higher scores for PTSD and depression. These patterns of association were also seen prominently in the use of military symbols. Those who used fragmented military symbols (eg, flag fragments, pieces of camouflage fabric or dog tags) reported more anxiety. These fragmented associations were associated with higher anxiety scores.

In contrast to fragmented symbols, those who used visual symbols of their military unit reported less PTSD and depression. These differences might imply that representation of the military unit is akin to identifying with a community and potentially reinforcing a sense of belonging. The development of a group identity in the military is well established as a means to ensure trust and effectiveness in a war zone through shared commitment and social cohesion.52–55 The findings highlight the protective role of a sense of belonging and group identity in the treatment process, beyond the period of deployment in the war zones. In fact, a strong sense of belonging could protect Air Force convoy operators against depression before and after their deployments.51 53 Some of the healing elements seen in art therapy are the promotion of self-exploration, self-expression, symbolic thinking, creativity and sensory stimulation.55 In a study of depression and dependency in SMs, it was found that art therapy offered a sense of control and served to integrate past experiences with present connections.55

The use of nature metaphors trended towards association with lower PTSD scores. This finding suggests that when SMs represented nature imagery, they might have been tapping into inner resources of strength and resilience. Reference to cultural historical characters was also associated with less depression and anxiety. Taken together, these visual metaphors might in general be indicative of sources of creativity and resilience. However, fragmented associations like depicting colours for specific emotions might not be associated with the higher levels of illness seen in PTSD and depressive symptoms. Imagery that represents this integration might be associated with more positive clinical scores compared with those representing more fragmented imagery.

This study has several limitations. All of the data related to the masks are self-reported secondary data collected as part of clinical practice. The findings indicate patterns of occurrence in visual imagery and scores on standardised clinical symptoms and are not representative of any causal relationships and must be interpreted accordingly. The control variables in the study including time in service, race/ethnicity and rank (officer or enlisted SM) were selected based on information in the literature. Most of the data are from male SMs; thus it is unclear if similar patterns might be seen among female SMs. Additional research is needed to determine why metaphorical depictions can denote the presence of different levels of psychological risk and resilience and how they relate to the demographic characteristics of the SM. In addition, further research is needed to determine why some themes were more strongly associated with specific clinical symptoms than others. One explanation for inconsistent findings across symptom scales is the varying number of participants who completed each scale. It is possible that the study was underpowered for identifying differences in the GAD that were consistent with the PCL and PHQ findings when the control variables were added to the model.

In conclusion, this study addresses a new area of enquiry associating patient clinical data with imagery to begin to develop a framework for how psychological states might be represented in visual media. The findings have the potential to help clinicians identify sources of strength and of risk factors for SMs with PTSD and TBI.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr Jesus Caban, Ms Kathy Williams, Ms Pamela Fried, Ms Rebekka Dieterich-Hartwell and Ms Adele Gonzaga for help with gathering literature and preparing the data set for analysis.

Footnotes

Contributors: All the authors contributed to the study as follows: GK led the study and conducted the review of the masks with MSW. JH conducted the statistical data analysis. LMF and TJD helped with manuscript review, including the discussion and implications sections. TJD designed the database protocol from which the clinical data for the analysis were used and patient consents were obtained.

Funding: We are grateful to the National Endowment for the Arts’ Creative Forces: The NEA Military Healing Arts Network for providing funding to support this study.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study was conducted with approval from the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (Bethesda, Maryland, USA) institutional review board, in accordance with all federal laws, regulations and standards of practice, as well as those of the Department of Defense and the Departments of the Army, Navy and Air Force and the partnering university.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The raw data were shared between the institutions as part of a data-sharing agreement. These data are not available for public sharing.

References

- 1. U.S. Government Accountability Office. VA mental health: Number of veterans receiving care, barriers faced, and efforts to increase access (GAO-12-12) [PDF file]. 2011. http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-12-12 (accessed 4 May 2018).

- 2. Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center. DoD worldwide numbers for TBI [PDF file]. Falls Church, VA: Department of Defense 2018. http://dvbic.dcoe.mil/dod-worldwide-numbers-tbi (accessed May 4 May 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 3. Blakeley K, Jansen DJ. Post-traumatic stress disorder and other mental health problems in the military: oversight issues for congress. Washington DC: Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tanielian T, Jaycox L. Invisible wounds of war: Psychological and cognitive injuries, their consequences, and services to assist recovery. Pittsburgh, PA: RAND Corporation, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dolan S, Martindale S, Robinson J, et al. Neuropsychological sequelae of PTSD and TBI following war deployment among OEF/OIF veterans. Neuropsychol Rev 2012;22:21–34. 10.1007/s11065-012-9190-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bahraini NH, Breshears RE, Hernández TD, et al. Traumatic brain injury and posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2014;37:55–75. 10.1016/j.psc.2013.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Williamson JB, Heilman KM, Porges EC, et al. A possible mechanism for PTSD symptoms in patients with traumatic brain injury: central autonomic network disruption. Front Neuroeng 2013;6:13 10.3389/fneng.2013.00013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Engel CC, Oxman T, Yamamoto C, et al. RESPECT-Mil: feasibility of a systems-level collaborative care approach to depression and post-traumatic stress disorder in military primary care. Mil Med 2008;173:935–40. 10.7205/MILMED.173.10.935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hesdorffer DC, Rauch SL, Tamminga CA. Long-term psychiatric outcomes following traumatic brain injury: a review of the literature. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2009;24:452–9. 10.1097/HTR.0b013e3181c133fd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hoops JR. The Effects of Multiple Combat-Related Military Deployments on Post Traumatic Stress Symptoms. Master of Social Work Clinical Research Papers. Paper 2012;39 http://sophia.stkate.edu/msw_papers/39. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Reger MA, Gahm GA, Swanson RD, et al. Association between number of deployments to Iraq and mental health screening outcomes in US Army soldiers. J Clin Psychiatry 2009;70:1266–72. 10.4088/JCP.08m04361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kline A, Falca-Dodson M, Sussner B, et al. Effects of repeated deployment to Iraq and Afghanistan on the health of New Jersey Army National Guard troops: implications for military readiness. Am J Public Health 2010;100:276–83. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.162925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wall PL. Posttraumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injury in current military populations: a critical analysis. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc 2012;18:278–98. 10.1177/1078390312460578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Coleman JA. Racial Differences in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Military Personnel: Intergenerational Transmission of Trauma as a Theoretical Lens. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma 2016;25:561–79. 10.1080/10926771.2016.1157842 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hall-Clark B, Sawyer B, Golik A, et al. Racial/Ethnic Differences in Symptoms of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rev 2016;12:124–38. 10.2174/1573400512666160505150257 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Baker DG, Heppner P, Afari N, Kilmer M, Harder L, et al. Trauma exposure, branch of service, and physical injury in relation to mental health among U.S. veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. Mil Med 2009;174:733–78. 10.7205/MILMED-D-03-3808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ramchand R, Schell TL, Karney BR, et al. Disparate prevalence estimates of PTSD among service members who served in Iraq and Afghanistan: possible explanations. J Trauma Stress 2010;23:n/a–68. 10.1002/jts.20486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rauch SL, Savage CR, Alpert NM, et al. The functional neuroanatomy of anxiety: a study of three disorders using positron emission tomography and symptom provocation. Biol Psychiatry 1997;42:446–52. 10.1016/S0006-3223(97)00145-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shin LM, McNally RJ, Kosslyn SM, et al. A positron emission tomographic study of symptom provocation in PTSD. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1997;821:521–3. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb48320.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Van der Kolk B. The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. New York, NY: Sage, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Barker VL, Brunk B. The Role of a Creative Arts Group in the Treatment of Clients with Traumatic Brain Injury. Music Therapy Perspectives 1991;9:26–31. 10.1093/mtp/9.1.26 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gonzalez-Dolginko B. In the Shadows of Terror: A Community Neighboring the World Trade Center Disaster Uses Art Therapy to Process Trauma. Art Therapy 2002;19:120–2. 10.1080/07421656.2002.10129408 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nanda U, Barbato Gaydos HL, Hathorn K, et al. Art and Posttraumatic Stress: A Review of the Empirical Literature on the Therapeutic Implications of Artwork for War Veterans With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Environ Behav 2010;42:376–90. 10.1177/0013916510361874 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Spiegel D, Malchiodi C, Backos A, et al. Art Therapy for Combat-Related PTSD: Recommendations for Research and Practice. Art Therapy 2006;23:157–64. 10.1080/07421656.2006.10129335 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Walker MS, Kaimal G, Koffman R, et al. Art therapy for PTSD and TBI: A senior active duty military service member’s therapeutic journey. Arts Psychother 2016;49:10–18. 10.1016/j.aip.2016.05.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Walker MS, Kaimal G, Gonzaga AML, et al. Active-duty military service members’ visual representations of PTSD and TBI in masks. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being 2017;12:1267317 10.1080/17482631.2016.1267317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fiet L. Mask-making and Creative Intelligence in Transcultural Education. Caribb Q 2014;60:58–72. 10.1080/00086495.2014.11672526 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kopytin A, Lebedev A. Humor, Self-Attitude, Emotions, and Cognitions in Group Art Therapy With War Veterans. Art Therapy 2013;30:20–9. 10.1080/07421656.2013.757758 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sargent PD, Campbell JS, Richter KE, et al. Integrative medical practices for combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychiatric Annals 2013;4:181–7. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lande RG, Tarpley V, Francis JL, et al. Combat Trauma Art Therapy Scale. Arts Psychother 2010;37:42–5. 10.1016/j.aip.2009.09.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Malchiodi C. Art therapy with combat veterans and military personnel Malchiodi CM, Handbook of Art Therapy. New York, NY: Guilford, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sargent PD, Campbell JS, Richter KE, et al. Integrative Medical Practices for Combat-Related Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Psychiatr Ann 2013;43:181–7. 10.3928/00485713-20130403-10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lobban J. The invisible wound: Veterans’ art therapy. International Journal of Art Therapy 2014;19:3–18. 10.1080/17454832.2012.725547 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gantt L, Tinnin LW. Support for a neurobiological view of trauma with implications for art therapy. Arts Psychother 2009;36:148–53. 10.1016/j.aip.2008.12.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Golub D. Symbolic expression in post-traumatic stress disorder: Vietnam combat veterans in art therapy. Arts Psychother 1985;12:285–96. 10.1016/0197-4556(85)90041-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Monson CM, Schnurr PP, Resick PA, et al. Cognitive processing therapy for veterans with military-related posttraumatic stress disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 2006;74:898–907. 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hines-Martin VP, Ising M. Use of art therapy with post-traumatic stress disordered veteran clients. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 1993;31:29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chambala A. Anxiety and Art Therapy: Treatment in the Public Eye. Art Therapy 2008;25:187–9. 10.1080/07421656.2008.10129540 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kim S, Kim G, Ki J. Effects of group art therapy combined with breath meditation on the subjective well-being of depressed and anxious adolescents. Arts Psychother 2014;41:519–26. 10.1016/j.aip.2014.10.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kimport ER, Hartzell E. Clay and Anxiety Reduction: A One-Group, Pretest/Posttest Design With Patients on a Psychiatric Unit. Art Therapy 2015;32:184–9. 10.1080/07421656.2015.1092802 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Morris FJ. Should art be integrated into cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders? Arts Psychother 2014;41:343–52. 10.1016/j.aip.2014.07.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sarid O, Cwikel J, Czamanski-Cohen J, et al. Treating women with perinatal mood and anxiety disorders (PMADs) with a hybrid cognitive behavioural and art therapy treatment (CB-ART). Arch Womens Ment Health 2017;20:229–31. 10.1007/s00737-016-0668-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bar-Sela G, Atid L, Danos S, et al. Art therapy improved depression and influenced fatigue levels in cancer patients on chemotherapy. Psychooncology 2007;16:980–4. 10.1002/pon.1175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gussak D. The effectiveness of art therapy in reducing depression in prison populations. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol 2007;51:444–60. 10.1177/0306624X06294137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Weathers FW, Huska JA, Keane TM. PCL·M for DSM·IV. Boston: National Center for PTSD - Behavioral Science Division, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1092–7. 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gibbons SW, Migliore L, Convoy SP, Greiner S, et al. Military mental health stigma challenges: Policy and practice considerations. J Nurse Practitioners 2014;10:365–72. 10.1016/j.nurpra.2014.03.021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zinzow HM, Britt TW, Pury CLS, et al. Barriers and facilitators of mental health treatment seeking among active-duty army personnel. Military Psychology 2013;25:514–35. 10.1037/mil0000015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ahronson A, Cameron JE. The nature and consequences of group cohesion in a military sample. Military Psychology 2007;19:9–25. 10.1080/08995600701323277 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bryan CJ, Heron EA. Belonging protects against post-deployment depression in military personnel. Depress Anxiety 2015;32:349–55. 10.1002/da.22372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Griffith J. Multilevel analysis of cohesion’s relation to stress, well-being, identification, disintegration, and perceived combat readiness. Mil Psychol 2002;14:217–39. 10.1207/S15327876MP1403_3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Oliver LW, Harman J, Hoover E, et al. A quantitative integration of the military cohesion literature. Military Psychology 1999;11:57–83. 10.1207/s15327876mp1101_4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Blomdahl C, Gunnarsson AB, Guregård S, et al. A realist review of art therapy for clients with depression. Arts in Psychotherapy 2013;40:322–30. 10.1016/j.aip.2013.05.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Salmon PR, Gerber NE. Disappointment, dependency, and depression in the military: The role of expectations as reflected in drawings. Art Therapy 1999;16:17–30. 10.1080/07421656.1999.10759347 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.