Abstract

Aims

To compare risks of early postpartum diabetes and prediabetes in Chinese women with and without gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) during pregnancy

Subjects and methods

Tianjin GDM observational study included 1263 women with a history of GDM and 705 women without GDM who participated in the urban GDM universal screening survey by using World Health Organization’s criteria. Postpartum diabetes and prediabetes were identified after a standard oral glucose tolerance test. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to assess risks of postpartum diabetes and prediabetes between women with and without GDM.

Results

During a mean follow-up of 3.53 years postpartum, 90 incident cases of diabetes and 599 incident cases of prediabetes were identified. Multivariable-adjusted hazard ratios among women with prior GDM, compared with those without it, were 76.1 (95% CI 23.6-246) for diabetes, and 25.4 (95% CI 18.2-35.3) for prediabetes. When the mean follow-up extended to 4.40 years, 121 diabetes and 616 prediabetes were identified. Women with prior GDM had a 13.0-fold multivariable-adjusted risk (95% CI 5.54-30.6) for diabetes and 2.15-fold risk (95% CI 1.76-2.62) for prediabetes compared with women without GDM. The positive associations between GDM and the risks of postpartum diabetes and pre-diabetes were significant and persistent when stratified by younger and older than 30 years at delivery, and normal weight and overweight participants.

Conclusions

The present study indicated that women with prior GDM had significantly increased risks for postpartum diabetes and prediabetes, with the highest risk at the first 3-4 years after delivery, compared with those without GDM.

Keywords: gestational diabetes mellitus, incidence, postpartum, prediabetes, diagnosis

Introduction

The prevalence of diabetes and prediabetes were 10.9% and 35.7% in 2013 in China, respectively1. The prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) has increased from 2.4% in 1999 to 8.1% in 2012 in urban China2, 3, now close to the US level (~7%)4. Currently, it is estimated that the health care costs associated with diabetes and GDM in the US are $ 278 billion and $1.3 billion per year5.

It is well recognized that women with prior GDM suffer higher risks of diabetes and prediabetes later in life6. Studies of postpartum risk of diabetes and prediabetes in women with prior GDM suggest early lifestyle intervention to prevent the progression to diabetes or prediabetes in this high risk population. However, the risks of postpartum diabetes in women with prior GDM might change at different conditions including different postpartum periods, maternal age, pre-pregnancy and postpartum body mass index (BMI), ethnicity, diagnostic criteria and methods of GDM during pregnancy, and diagnostic criteria and methods of postpartum diabetes. Until now, no previous studies have carried out an urban GDM universal screening survey by using World Health Organization (WHO)’s criteria and very few studies have assessed early postpartum diabetes and prediabetes by using a standard oral glucose tolerance test among women with and without a history of GDM. In the present analysis of the Tianjin GDM observational study, we aimed to investigate risks of early postpartum diabetes and prediabetes among women with and without a history of GDM.

Subjects and methods

Tianjin GDM screening project

Tianjin is the fourth largest city in China, only 30-minute distance by train from Beijing. There are six central districts in Tianjin with about 4.3 million residents. In 1999, the Tianjin Women’s and Children’s Health Center launched an urban universal screening of GDM using WHO’s criteria in all six central districts2. The screening rate was reported to be >91% between 1999 and 20082. We used a 1-hour glucose screening test with 50g glucose load at 26-30 gestational weeks. If the 1-hour glucose level was over 7.8 mmol/L, another 2-h oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) with 75g glucose load would be performed at the Tianjin Women’s and Children’s Health Center. GDM diagnosis was made as per WHO criteria: a 75-g glucose 2-h OGTT result confirming either diabetes (fasting glucose ≥7 mmol/l or 2-hour glucose ≥11.1 mmol/l) or impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) (2-hour glucose ≥7.8 and <11.1 mmol/l)7.

Study samples

Totally 76,325 women were screened from 2005 to 2009, among whom 4644 women were diagnosed as GDM and 71,681 were free of GDM (Online Figure 1). We invited all 4644 GDM women to participate in the Tianjin Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Prevention Program (TGDMPP)8–11. Finally, 1263 women with GDM finished the baseline survey including a questionnaire and an OGTT between August 2009 and July 2011. Among these 1263 women with GDM, 83 were newly diagnosed diabetes according to the OGTT results and the rest 1180 women with GDM were randomized into an intervention group (n=586) and a “usual care” control group (n=594) in the TGDMPP. In parallel, we also enrolled in the Tianjin GDM observational study 705 non-GDM women and their children with birth dates and sex frequency-matched to the 594 children of GDM women in the “usual care” group and 83 children of GDM women who were newly diagnosed diabetes at baseline survey. The study was approved by the Human Subjects Committee of the Tianjin Women’s and Children’s Health Center. All the participants provided written informed consent.

Questionnaires and measurements

All study participants filled in a questionnaire about their socio-demographics (age, marital status, education, income, and occupation), history of GDM, family history (diabetes, CHD, stroke, cancer and hypertension), medical history (hypertension, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia), pregnancy outcomes (pre-pregnancy weight, weight gain in pregnancy, and number of children), dietary habits (a self-administered food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) to measure the frequency and quantity of intake of 33 major food groups and beverages during the past year)12, alcohol intake, smoking habits, passive smoking, and physical activity (the frequency and duration of leisure time and sedentary activities) at the postpartum baseline survey. They also completed the 3-day 24-hour food records using methods for dietary record collections taught by a dietician. The performance of 3-day 24-hour food records12, the FFQ12, and the above questionnaire on assessing physical activity13, 14 have been validated in the China National Nutrition and Health Survey in 2002.

Body weight and height were measured using the standardized protocol by specially trained research doctors. BMI was calculated as the body weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters. Waist circumference was measured at the horizontal level between the inferior costal margin and the iliac crest on the mid-axillary line with women in their standing position. Blood samples were collected in all participants after an overnight fast of at least 12 hours. Participants without a self-reported history of diabetes were given a standard 75-g glucose OGTT test. Plasma glucose was measured on an automatic analyzer (Toshiba TBA-120FR, Japan). Coefficient of variance was 4.42% for glucose.

Definition of postpartum diabetes and prediabetes

We used American Diabetes Association (ADA)’s criteria15 for the diagnosis of diabetes and prediabetes. Diabetes was defined as fasting glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/L, and/or 2-h glucose ≥ 11.1 mmol/L. Prediabetes was defined as either impaired fasting glucose (fasting glucose ≥5.6 mmol/L and <7.0 mmol/L) or IGT (2-h glucose ≥ 7.8 mmol/L and <11.1 mmol/L). Those using antidiabetic drugs in the examination were also included into the type 2 diabetes cases. Until now, GDM women in both intervention and control groups in the TGDMPP finished baseline and subsequent annual OGTT during the three years follow-up visits. The present study included two different postpartum follow-up periods: early postpartum follow-up (both GDM and non-GDM women at baseline survey) and extended postpartum follow-up (GDM women in the interventional group and non-GDM women at baseline survey, and GDM women in the control group at the Year 3 follow-up visit).

Statistical analysis

Standard t test and chi-square test were used in the comparison of continuous variables and categorical variables between women with GDM and without GDM. Cox proportional hazard regression analysis was used to assess risks of postpartum diabetes and prediabetes between women with and without GDM. All analyses were adjusted for age (Model 1), and then for education, family income, family history of diabetes, smoking, passive smoking, alcohol drinking, leisure-time physical activity, sleeping time, dietary fiber, sweetened beverage drinking, energy intakes of fat, protein, and carbohydrate (Model 2), and further for BMI (Model 3). P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed by IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA).

Results

General characteristics of the study population at baseline were given in Table 1. Women with GDM were slightly older after delivery and younger at baseline survey. Their BMI, HbA1C, fasting and 2-h glucose at baseline were higher. They were less educated and had less family income. In addition, they were less alcohol drinkers, less physically active, and had more energy intakes as compared with those who were free of GDM.

Table 1.

Characteristics of women with and with gestational diabetes (GDM), Tianjin, China

| Non-GDM | GDM with early postpartum follow-up | GDM with extended postpartum follow-up | P valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of participants | 705 | 1263 | 1263 | |

| Age at delivery, years | 29.7 ± 2.83 | 30.1 ± 3.50 | 30.1 ± 3.50 | 0.008 |

| Age at baseline, years | 35.4 ± 2.95 | 32.4 ± 3.52 | 33.7 ± 4.13 | <0.001 |

| Duration after delivery, years | 5.74 ± 1.19 | 2.29 ± 0.88 | 3.65 ± 2.17 | <0.001 |

| Weight gain during pregnancy, kg | 18.3 ± 6.67 | 16.8 ± 5.99 | 16.8 ± 5.99 | <0.001 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 22.9 ± 3.68 | 24.2 ± 3.93 | 24.3 ± 3.96 | <0.001 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 75.8 ± 8.26 | 80.6 ± 9.47 | 80.6 ± 9.48 | <0.001 |

| Fasting glucose, mmol/l | 5.23 ± 0.52 | 5.38 ± 0.97 | 5.43 ± 0.99 | <0.001 |

| 2 hour glucose, mmol/l | 6.14 ± 1.41 | 7.08 ± 2.49 | 7.24 ± 2.65 | <0.001 |

| HbA1c, mmol/mol | 35 ±3 | 38 ± 8 | 38 ± 8 | <0.001 |

| HbA1c, % | 5.3 ± 0.2 | 5.6 ±0.7 | 5.6 ± 0.7 | <0.001 |

| Education, % | <0.001 | |||

| <13 years | 10.4 | 22.5 | 22.5 | |

| 13-16 years | 75.5 | 70.1 | 70.1 | |

| ≥16 years | 14.2 | 7.4 | 7.4 | |

| Income, % | <0.001 | |||

| <5000 yuan per month | 5.4 | 27.5 | 27.5 | |

| 5000-8000 yuan per month | 15.5 | 36.9 | 36.9 | |

| ≥8000 yuan per month | 79.1 | 35.6 | 35.6 | |

| Family history of diabetes, % | 27.1 | 35.7 | 35.7 | <0.001 |

| Current smoking, % | 4.0 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 0.355 |

| Passive smoking, % | 55.2 | 53.8 | 58.0 | 0.572 |

| Current alcohol drinker, % | 32.1 | 21.8 | 26.9 | <0.001 |

| Leisure time physical activity, % | <0.001 | |||

| 0 min per day | 61.7 | 78.8 | 71.7 | |

| 1-29 min per day | 33.8 | 19.1 | 25.3 | |

| ≥30 min per day | 4.5 | 2.1 | 3.0 | |

| Sleeping time, hours/day | 7.48 ± 0.95 | 7.81 ± 1.06 | 7.70 ± 1.02 | <0.01 |

| Energy consumption, kcal/daya | 1627 ± 381 | 1676 ± 436 | 1704 ± 432 | 0.01 |

| Fiber, g/day | 11.6 ± 4.42 | 12.2 ± 4.75 | 12.3 ± 4.62 | 0.01 |

| Fat, % energy | 31.1 ± 5.65 | 33.5 ± 6.34 | 33.1 ± 6.12 | <0.001 |

| Carbohydrate, % energy | 52.3 ± 6.81 | 49.5 ± 7.30 | 50.2 ± 7.04 | <0.001 |

| Protein, % energy | 16.6 ± 2.62 | 17.0 ± 2.78 | 16.7 ± 2.68 | 0.006 |

| Sweetened beverage drink, % | 77.9 | 75.5 | 78.1 | 0.223 |

Dietary intakes are assessed by 3-day 24-h food records.

P values between non-GDM and GDM with early postpartum follow-up.

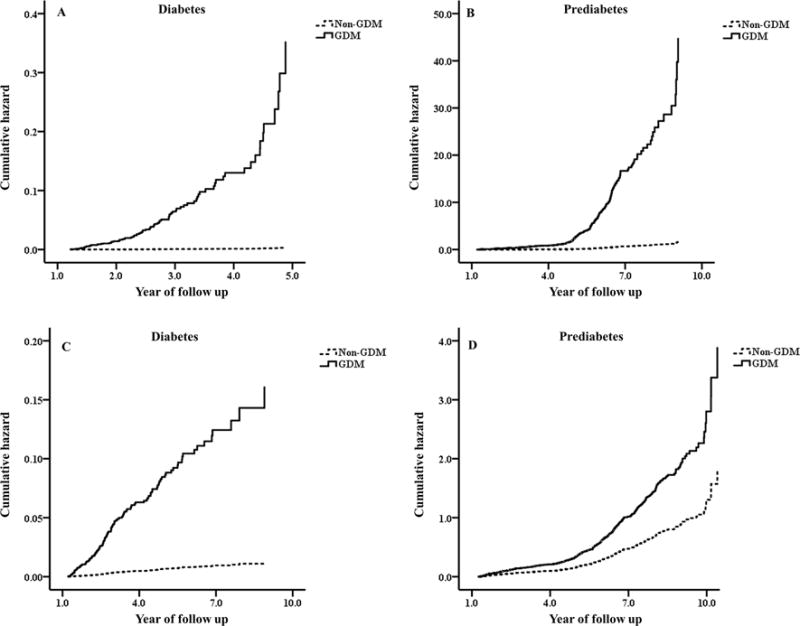

During a mean follow-up of 3.53 years postpartum, there were 90 incident cases of diabetes and 599 incident cases of prediabetes. The incident rates of diabetes and prediabetes were 28.7/1000 person-years and 150.3/1000 person-years in GDM women, and 1.73/1000 person-years and 49.3/1000 person-years in non-GDM women, respectively. Multivariable-adjusted (age, education, family income, family history of diabetes, smoking, passive smoking, alcohol drinking, leisure-time physical activity, sleeping time, dietary fiber, sweetened beverage drinking, energy intakes of fat, protein, and carbohydrate, and BMI – Model 3) hazard ratios among women with prior GDM, compared with those without GDM, were 76.1 (95% CI 23.6-246) for diabetes, and 25.4 (95% CI 18.2-35.3) for prediabetes, respectively (Table 2 and Figure 1. A and B). When the mean follow-up extended to 4.40 years, there were 121 incident cases of diabetes and 616 incident cases of prediabetes. The incident rates of diabetes and prediabetes changed to 24.7/1000 person-years and 98.1/1000 person-years in GDM women, and 1.73/1000 person-years and 49.3/1000 person-years in non-GDM women, respectively. Women with prior GDM had a 13.0-fold multivariable-adjusted risk (95% CI 5.54-30.6) for diabetes and 2.15-fold risk (95% CI 1.76-2.62) for prediabetes compared with women without GDM (Table 2 and Figure 1. C and D).

Table 2.

Hazard ratio of diabetes and pre-diabetes among women with and without GDM at different follow-up period

| Diabetes | Pre-diabetesa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Non-GDM | GDM | Non-GDM | GDM | |

| GDM women with early postpartum follow-up (mean 3.53 years) | ||||

| No. of participants | 705 | 1263 | 698 | 1180 |

| No. of cases | 7 | 83 | 198 | 401 |

| Pearson-years | 4052 | 2886 | 4014 | 2668 |

| Multiple adjusted hazard ratios | ||||

| Model 1 | 1 | 113 (37.3-346) | 1 | 29.0 (21.2-39.5) |

| Model 2 | 1 | 91.0 (28.2-294) | 1 | 27.0 (19.5-37.5) |

| Model 3 | 1 | 76.1 (23.6-246) | 1 | 25.4 (18.2-35.3) |

| GDM women with extended postpartum follow-up (mean 4.40 years) | ||||

| No. of participants | 705 | 1263 | 698 | 1149 |

| No. of cases | 7 | 114 | 198 | 418 |

| Pearson-years | 4052 | 4609 | 4014 | 4262 |

| Multiple adjusted hazard ratios | ||||

| Model 1 | 1 | 17.0 (7.92-36.6) | 1 | 2.20 (1.85-2.62) |

| Model 2 | 1 | 15.6 (6.62-36.7) | 1 | 2.30 (1.89-2.80) |

| Model 3 | 1 | 13.0 (5.54-30.6) | 1 | 2.15 (1.76-2.62) |

Model 1 was adjusted for age; Model 2 was adjusted for age, education, family income, family history of diabetes, current smoking, passive smoking, current alcohol drinking, leisure time physical activity, sleeping time, energy consumption, fiber, fat, protein and carbohydrate consumption, and sweetened beverage drinking; Model 3 was adjusted for factors in Model 2 and also body mass index.

Excluding type 2 diabetes.

Figure 1.

The cumulative incidence curve of type 2 diabetes (A, early postpartum follow-up and C, extended postpartum follow-up) and pre-diabetes (B, early postpartum follow-up and D, extended postpartum follow-up) among women with and without GDM. All analyses were adjusted for age, education, family income, family history of diabetes, current smoking, passive smoking, current alcohol drinking, leisure time physical activity, sleeping time, dietary fiber, sweetened beverage drinking, energy intakes of fat, protein, and carbohydrate, and body mass index.

Multivariable-adjusted positive associations between GDM and the risks of postpartum diabetes and pre-diabetes were present in women aged younger and older than 30 years at delivery (Table 3). Similarly, the positive association was observed in both healthy weight women and overweight women. There were no statistically significant interactions of age, BMI and GDM status on the risks of postpartum diabetes and pre-diabetes (all P for interaction >0.25).

Table 3.

Hazard ratio of diabetes and pre-diabetes among women with and without GDM by various subgroups

| Diabetes | Pre-diabetesa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Non-GDM | GDM | Non-GDM | GDM | |

| Women with early postpartum follow-up (mean 3.53 years)b | ||||

| Body mass index (kg/m2)c | ||||

| <25 | 1 | 50.2 (13.1-193) | 1 | 26.8 (17.8-40.5) |

| ≥25 | 1 | 164 (18.3-1464) | 1 | 25.3 (14.3-44.8) |

| Age at delivery groups (years)c | ||||

| <30 | 1 | 132 (22.6-774) | 1 | 28.6 (18.2-44.6) |

| ≥30 | 1 | 60.0 (9.93-363) | 1 | 29.3 (16.8-50.9) |

| Women with extended postpartum follow-up (mean 4.40 years) b | ||||

| Body mass index (kg/m2)c | ||||

| <25 | 1 | 8.45 (2.67-26.8) | 1 | 2.47 (1.92-3.18) |

| ≥25 | 1 | 22.0 (5.26-91.9) | 1 | 1.78 (1.29-2.46) |

| Age at delivery groups (years)c | ||||

| <30 | 1 | 19.1 (5.76-63.3) | 1 | 2.20 (1.69-2.85) |

| ≥30 | 1 | 7.91 (2.36-26.5) | 1 | 2.14 (1.57-2.91) |

Excluding type 2 diabetes.

All analyses were adjusted for age, education, family income, family history of diabetes, current smoking, passive smoking, current alcohol drinking, leisure time physical activity, sleeping time, energy consumption, fiber, fat, protein and carbohydrate consumption, sweetened beverage drinking, and body mass index, other than the variables for stratification.

All P for interaction >0.25.

Discussion

In this large GDM observational study, women with a history of GDM during pregnancy had a significantly increased risk of postpartum diabetes and prediabetes compared with women without GDM, and this risk was the highest at the first 3-4 years after delivery.

The prevalence of GDM is high among Asian women (~10%) compared with other racial/ethnic groups (5-8%) in the US16–19. In China, the prevalence of GDM has increased from 2.4% in 1999 to 8.2% in 20122, 3, now similar to the level in US women (~7%)4. Recent studies have found that Asian Americans with GDM are more likely to develop diabetes than other racial/ethnic women with GDM in the US20 although Asian Americans generally have lower BMI and the prevalence of overweight/obesity than other racial/ethnic Americans21, 22. However, very few studies investigated the postpartum risks of diabetes and prediabetes in Chinese women with a history of GDM. In a cohort of Chinese women living in Hong Kong, 9.0% of women with a history of GDM developed type 2 diabetes after a median follow-up of 8 years23.

It has been suggested that the risk of postpartum diabetes in women with prior GDM might change due to different races and ethnicities24, different postpartum periods, maternal age, pre-pregnancy and postpartum BMI, diagnostic criteria of GDM during pregnancy, and diagnostic criteria of postpartum diabetes. For example, Bao W, et al. reported a higher risk of postpartum diabetes among GDM women during up to 18 years of follow-up, especially among GDM women with higher baseline BMI and more weight gain after GDM development by a standard questionnaire25. Since most of previous studies only used electronic medical records to identify symptomatic women at high risks of GDM and postpartum diabetes, these studies could have missed some asymptomatic cases of GDM and postpartum diabetes. No previous studies have reported the results based on an urban GDM universal screening survey by using the standard WHO’s criteria, and very few studies have assessed early postpartum diabetes and prediabetes by using a standard oral glucose tolerance test among women with and without a history of GDM. Tianjin GDM observational study was the only study with a large sample size including 1263 women with a history of GDM and 705 women without GDM from 76,325 women who participated in the whole population’s GDM universal screening survey by using the WHO’s criteria. All 1263 women with prior GDM and 705 women with GDM had a standard oral glucose tolerance test at 1-9 years postpartum to identify postpartum diabetes and prediabetes using the ADA’s criteria. In addition, about 95% of pregnancy women in the Tianjin urban area finished a fasting glucose examination during the first trimester26. Women with diabetes before pregnancy or with asymptomatic diabetes during the early pregnancy were excluded in the present study. Thus the present study provided a comprehensive and accurate estimation of GDM with postpartum diabetes and prediabetes.

Two early reviews have reported that women with prior GDM have a 7-fold higher risk of postpartum diabetes compared with women without GDM6, 27. A recent review has also indicated that the adjusted odds ratios of diabetes among GDM women compared with non-GDM women at <3, 3-6 and 6-10 years after delivery were 5.37, 16.55 and 8.20, respectively28. The present study found that women with prior GDM had a 76.1-fold risk for diabetes and a 25.4-fold risk for prediabetes compared with women without GDM at a mean follow-up of 3.53 years postpartum. When the mean follow-up extended to 4.40 years, women with prior GDM had a 13.0-fold risk for diabetes and a 2.15-fold risk for prediabetes compared with women without GDM. The present study demonstrated that women with prior GDM had the highest risk of postpartum diabetes at the first 3-4 years after delivery compared with women without GDM, which was similar to the trend from one recent meta-analysis that the risk of postpartum diabetes among women with GDM increased to a peak at the first 3 to 6 years and then attenuated28. Explanations might include more pronounced beta cell defect and susceptible genetic variants among women with early onset of postpartum diabetes29. Several studies have confirmed that antepartum characteristics might also contribute to the onset of postpartum diabetes30, 31. However, in our cohort, there were no significant differences in antepartum or postpartum BMI, weight gain during pregnancy, and the GDM women’s insulin treatment during pregnancy among women with early onset of postpartum diabetes compared with women with late onset of postpartum diabetes. Whether this risk trend resulted from other factors remains unknown and needs further studies. Thus we implied that women with prior GDM represents a high risk population that should be targeted for early postpartum lifestyle intervention in order to prevent or delay the onset of type 2 diabetes. TGDMPP is an ongoing trial to evaluate the effect of early postpartum lifestyle intervention on the progress of diabetes.

In subgroup analyses of the present study, overweight women with prior GDM seemed to show a much higher risk for postpartum diabetes than normal weight women with prior GDM compared with overweight and normal weight women without GDM, which was similar with the results in other studies32, 33. Overweight is a definite risk factor for diabetes and prediabetes. Thus early postpartum lifestyle intervention on weight loss is strongly recommended to prevent or delay type 2 diabetes and pre-diabetes among overweight women with a history of GDM. Meanwhile, we also noticed that women with GDM who were younger than 30 years old at delivery tended to have higher risks for postpartum diabetes and prediabetes than women with prior GDM who were older than 30 years old at delivery, which should be taken more attention. The early postpartum 2-h OGTT might help identify asymptomatic women with diabetes and prediabetes at a younger age, which could partly explain the higher risk of women at a younger age. In addition, GDM women who were younger at delivery in our cohort were more exposed to positive family history of diabetes. These women may be of higher genetic susceptibility to glucose intolerance as they developed GDM even at a younger age. Patients diagnosed as type 2 diabetes at a younger age usually have much higher risks of macro-34 and microvascular diseases35 than those developing type 2 diabetes later. The findings of the present study will greatly promote favorable changes in the Public Health Policy regarding prevention of the progress of diabetes among women with a history of GDM.

A unique advantage of the present study is that diagnoses of GDM at 26–30 gestational weeks were based on the whole population’s GDM universal screening by using the WHO’s criteria after a 2 h 75 g OGTT. The diagnosis of postpartum diabetes and prediabetes was based on the ADA’s criteria after a 2 h 75 g OGTT. Our study is the only study to provide a comprehensive and accurate estimation of GDM with postpartum diabetes and prediabetes. Another important strength of our study is the large sample size of both women with and without a history of GDM. One limitation of this study is the return rate of the initial invitation with only 27% of all GDM women. Although there were no differences in age, 2 h glucose, fasting glucose, the prevalence of IGT and diabetes at 26–30 gestational weeks, and OGTT tests between those returned and those not returned, whether other differences between groups existed cannot be verified. Second, we have no data on 1 h glucose and 3 h glucose during pregnancy since we used the WHO’s diagnostic criteria for GDM. Finally, due to the one-child policy from 1979 to 201536, the birth rates were lower in China than in other countries, which may influence the results. It has been considered that increasing numbers of parity were associated with an increasing risk of type 2 diabetes37. However, since only 2.44% of the women included in the Tianjin GDM screening project have a history of more than 1 parity2, parity bias is not considered in the present study.

In conclusion, we reported a substantially increased risk of postpartum diabetes and prediabetes in women with prior GDM compared with those without GDM, and this risk was the highest at the first 3-4 years after delivery. An early postpartum lifestyle intervention might prevent and delay diabetes and prediabetes risk among women with a history of GDM.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to appreciate all families for participating in the Tianjin Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Prevention Program.

Funding. This study is supported by the grant from European Foundation for the Study of Diabetes (EFSD)/Chinese Diabetes Society (CDS)/Lilly programme for Collaborative Research between China and Europe, Tianjin Women’s and Children’s Health Center, and Tianjin Public Health Bureau. Dr. Hu was partly supported by the grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01DK100790) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (U54GM104940) of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Cuilin Zhang is supported by the Intramural Research Program of Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health.

The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study, collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data, preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript, and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Author Contributions: Y.S., P.W., and G.H. designed the study, acquired data, performed statistical analyses, and drafted the manuscript. H.T. and J.T. designed the study and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. L.W., S.Z., H.L, W.L., N.L., W.L., J.L., and J.W. acquired data, performed statistical analyses, and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. C.Z., X.Y., and Z.Y. critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. G.H. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References

- 1.Wang L, Gao P, Zhang M, Huang Z, Zhang D, Deng Q, Li Y, Zhao Z, Qin X, Jin D, et al. Prevalence and Ethnic Pattern of Diabetes and Prediabetes in China in 2013. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2017;317:2515–2523. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.7596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang F, Dong L, Zhang C, Li B, Wen J, Gao W, Sun S, Lv F, Tian H, Tuomilehto J, et al. Increasing prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus in Chinese women from 1999 to 2008. Diabetic Medicine. 2011;28:652–657. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2010.03205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leng J, Shao P, Zhang C, Tian H, Zhang F, Zhang S, Dong L, Li L, Yu Z, Chan JC, et al. Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Its Risk Factors in Chinese Pregnant Women: A Prospective Population-Based Study in Tianjin, China. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0121029. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Diabetes Association. Gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(Suppl 1):S103–105. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.2007.s103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dall TM, Yang W, Halder P, Pang B, Massoudi M, Wintfeld N, Semilla AP, Franz J, Hogan PF. The economic burden of elevated blood glucose levels in 2012: diagnosed and undiagnosed diabetes, gestational diabetes mellitus, and prediabetes. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:3172–3179. doi: 10.2337/dc14-1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bellamy L, Casas JP, Hingorani AD, Williams D. Type 2 diabetes mellitus after gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373:1773–1779. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60731-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Consultation WHO. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 1999. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu G, Tian H, Zhang F, Liu H, Zhang C, Zhang S, Wang L, Liu G, Yu Z, Yang X, et al. Tianjin Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Prevention Program: Study design, methods, and 1-year interim report on the feasibility of lifestyle intervention program. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012;98:508–517. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2012.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu H, Zhang C, Zhang S, Wang L, Leng J, Liu D, Fang H, Li W, Yu Z, Yang X, et al. Joint effects of pre-pregnancy body mass index and weight change on postpartum diabetes risk among gestational diabetes women. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2014;22:1560–1567. doi: 10.1002/oby.20722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu H, Zhang S, Wang L, Leng J, Li W, Li N, Li M, Qiao Y, Tian H, Tuomilehto J, et al. Fasting and 2-hour plasma glucose, and HbA1c in pregnancy and the postpartum risk of diabetes among Chinese women with gestational diabetes. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2016;112:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2015.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li W, Zhang S, Liu H, Wang L, Zhang C, Leng J, Yu Z, Yang X, Tian H, Hu G. Different associations of diabetes with beta-cell dysfunction and insulin resistance among obese and nonobese Chinese women with prior gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:2533–2539. doi: 10.2337/dc14-0573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li YP, He YN, Zhai FY, Yang XG, Hu XQ, Zhao WH, Ma GS. Comparison of assessment of food intakes by using 3 dietary survey methods. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2006;40:273–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma G, Luan D, Liu A, Li Y, Cui Z, Hu X, Yang X. The analysis and evaluation of a physical activity questionnaire of Chinese employed population. Ying Yang Xue Bao. 2007;29:217–221. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma G, Luan D, Li Y, Liu A, Hu X, Cui Z, Zhai F, Yang X. Physical activity level and its association with metabolic syndrome among an employed population in China. Obesity Review. 2008;9(Suppl 1):113–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.ADA. 2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2018. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:S13–s27. doi: 10.2337/dc18-S002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chu SY, Abe K, Hall LR, Kim SY, Njoroge T, Qin C. Gestational diabetes mellitus: All Asians are not alike. Preventive Medicine. 2009;49:265–268. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferrara A, Kahn HS, Quesenberry CP, Riley C, Hedderson MM. An increase in the incidence of gestational diabetes mellitus: Northern California, 1991-2000. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2004;103:526–533. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000113623.18286.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dabelea D, Snell-Bergeon JK, Hartsfield CL, Bischoff KJ, Hamman RF, McDuffie RS. Increasing prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) over time and by birth cohort: Kaiser Permanente of Colorado GDM Screening Program. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:579–584. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.3.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Y, Chen L, Xiao K, Horswell R, Besse J, Johnson J, Ryan DH, Hu G. Increasing incidence of gestational diabetes mellitus in louisiana, 1997-2009. Journal of Women’s Health (Larchmt) 2012;21:319–325. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2011.2838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Y, Chen L, Horswell R, Xiao K, Besse J, Johnson J, Ryan DH, Hu G. Racial differences in the association between gestational diabetes mellitus and risk of type 2 diabetes. Journal of Women’s Health (Larchmt) 2012;21:628–633. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2011.3318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oza-Frank R, Ali MK, Vaccarino V, Narayan KM. Asian Americans: diabetes prevalence across U.S. and World Health Organization weight classifications. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1644–1646. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shai I, Jiang R, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Colditz GA, Hu FB. Ethnicity, obesity, and risk of type 2 diabetes in women: a 20-year follow-up study. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1585–1590. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tam WH, Yang XL, Chan JC, Ko GT, Tong PC, Ma RC, Cockram CS, Sahota D, Rogers MS. Progression to impaired glucose regulation, diabetes and metabolic syndrome in Chinese women with a past history of gestational diabetes. Diabetes/metabolism Research and Reviews. 2007;23:485–489. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xiang AH, Li BH, Black MH, Sacks DA, Buchanan TA, Jacobsen SJ, Lawrence JM. Racial and ethnic disparities in diabetes risk after gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 2011;54:3016–3021. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2330-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bao W, Yeung E, Tobias DK, Hu FB, Vaag AA, Chavarro JE, Mills JL, Grunnet LG, Bowers K, Ley SH, et al. Long-term risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in relation to BMI and weight change among women with a history of gestational diabetes mellitus: a prospective cohort study. Diabetologia. 2015;58:1212–1219. doi: 10.1007/s00125-015-3537-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dong L, Liu E, Guo J, Pan L, Li B, Leng J, Zhang C, Zhang Y, Li N, Hu G. Relationship between maternal fasting glucose levels at 4-12 gestational weeks and offspring growth and development in early infancy. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2013;102:210–217. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2013.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim C, Newton KM, Knopp RH. Gestational diabetes and the incidence of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1862–1868. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.10.1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Song C, Lyu Y, Li C, Liu P, Li J, Ma RC, Yang X. Long-term risk of diabetes in women at varying durations after gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis with more than 2 million women. Obes Rev. 2018;19:421–429. doi: 10.1111/obr.12645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kwak SH, Choi SH, Jung HS, Cho YM, Lim S, Cho NH, Kim SY, Park KS, Jang HC. Clinical and genetic risk factors for type 2 diabetes at early or late post partum after gestational diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:E744–752. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-3324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jang HC. Gestational diabetes in Korea: incidence and risk factors of diabetes in women with previous gestational diabetes. Diabetes Metab J. 2011;35:1–7. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2011.35.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buchanan TA, Xiang A, Kjos SL, Lee WP, Trigo E, Nader I, Bergner EA, Palmer JP, Peters RK. Gestational diabetes: antepartum characteristics that predict postpartum glucose intolerance and type 2 diabetes in Latino women. Diabetes. 1998;47:1302–1310. doi: 10.2337/diab.47.8.1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cianni GD, Ghio A, Resi V, Volpe L. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: An Opportunity to Prevent Type 2 Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease in Young Women. Women’s Health. 2010;6:97–105. doi: 10.2217/whe.09.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee AJ, Hiscock RJ, Wein P, Walker SP, Permezel M. Gestational diabetes mellitus: clinical predictors and long-term risk of developing type 2 diabetes: a retrospective cohort study using survival analysis. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:878–883. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huo X, Gao L, Guo L, Xu W, Wang W, Zhi X, Li L, Ren Y, Qi X, Sun Z, et al. Risk of non-fatal cardiovascular diseases in early-onset versus late-onset type 2 diabetes in China: a cross-sectional study. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology. 2016;4:115–124. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00508-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li L, Ji L, Guo X, Ji Q, Gu W, Zhi X, Li X, Kuang H, Su B, Yan J, et al. Prevalence of microvascular diseases among tertiary care Chinese with early versus late onset of type 2 diabetes. Journal of Diabetes and Its Complications. 29:32–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2014.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zeng Y, Hesketh T. The effects of China’s universal two-child policy. Lancet. 2016;388:1930–1938. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31405-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Naver KV, Lundbye-Christensen S, Gorst-Rasmussen A, Nilas L, Secher NJ, Rasmussen S, Ovesen P. Parity and risk of diabetes in a Danish nationwide birth cohort. Diabet Med. 2011;28:43–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2010.03169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.