Abstract

Phenazine is known to regroup planar nitrogen-containing heterocyclic compounds. It was used here to enhance the bioavailability of the biologically important compound iodinin, which is near insoluble in aqueous solutions. Its water solubility has led to the development of new formulations using diverse amphiphilic α-cyclodextrins (CDs). With the per-[6-desoxy-6-(3-perfluorohexylpropanethio)-2,3-di-O-methyl]-α-CD, we succeeded to get iodinin-loaded nanoformulations with good parameters such as a size of 97.9 nm, 62% encapsulation efficiency and efficient control release. The study presents an interesting alternative to optimizing the water solubility of iodinin by chemical modifications of iodinin.

Keywords: Iodinin, solubility, amphiphilic α-cyclodextrin, nanoparticles, encapsulation

Introduction

Phenazine is a dibenzo annulated pyrazine present in many natural products1–3 and has become the parent substance of many synthetic bioactive molecules4–6. The broad spectrum of biological activities of phenazine explains the success of research programs exploiting this scaffold. The most striking examples are the targeting of antibiotic-tolerant bacterial biofilms and Mycobacterium tuberculosis by halogenated phenazines7. Other derivatives such as endophenazine G showed activity against community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus8. Phenazine-1-carboxylic acid derivatives exhibit fungicidal activities9 and finally numerous phenazines were developed as anti-cancer agents10, for example, the novel pyrano[3,2-a]phenazine derivatives demonstrated antiproliferative activity against the HepG2 cancer cell line11.

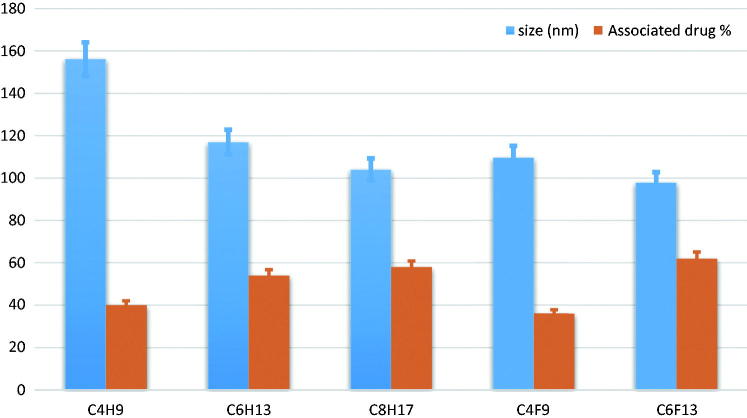

Iodinin (Figure 1) was first discovered in 193912 within Chromobacterium iodinum bacterial cultures. In 1943, McIlwain demonstrated its anti-streptococcal action13. For the last 75 years, iodinin has been isolated from diverse soil bacteria (e.g. Brevibacterium iodinum14, Pseudomonas phenazinium15, Nocardiopsis dassonvillei16, and Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans17), or marine bacteria (e.g. Actinomadura sp.18, Streptosporangium sp.19). Recently, recombinant Pseudomonas strains were used successfully to propose an alternative for the biosynthesis of natural phenazines20. Iodinin displays other biological activities, including anti-microbial and cytotoxic properties21,22. Actually, it is worth noting that iodinin showed remarkable selective toxicity to acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) and acute promyelocytic leukaemia (APL) cells, with various proposed mechanisms of action suggested such as DNA intercalation and activation of apoptotic signalling proteins (e.g. caspase-3)19.

Figure 1.

Structure of iodinin (1,6-dihydroxyphenazine 5,10-dioxide).

The first total synthesis of iodinin was recently described by Viktorsson et al.21. The physical chemical properties of iodinin can be summarised as follows: it is a dark red solid, stable in acidic solution, unstable in alkali. Iodinin’s solubility in different solvent can be summarised as follows: it is soluble in benzene, toluene, xylene, carbon disulphide, chloroform, ethyl acetate, THF, concentrated sulfuric acid, glacial acetic acid and sodium hydroxide. It is also slightly soluble in hot alcohol. In parallel, iodinin is practically insoluble in cold alcohol, ether, acetic acid, petroleum ether, or amyl alcohol21. Finally, iodinin is absolutely insoluble in water. In addition, various assays21 showed that iodinin solutions turned (i) pink when it was solubilised in most solvents; (ii) purple in chloroform with formation of crystals with a coppery sheen; (iii) red in glacial acetic acid and (iv) brilliant blue in sodium hydroxide with the deposition of green crystals from unstable sodium derivatives. It thus appears that iodinin is a bioactive molecule, which is difficult to manage in most biological investigations. To overcome this issue, we envisaged to complex iodinin with cyclodextrins (CDs) to increase aqueous solubility and bioavailablility.

Amphiphilic CD derivatives have been available for decades23,24 mainly to overcome problems of native CDs that limit their applications in pharmaceutical fields. Indeed, since dissociation takes place too readily upon dilution, untimely release may take place during administration to the patient, so that inclusion complexes inside simple water-soluble CD appear ineffective for drug delivery applications. In fact, the use of amphiphilic CDs (i) enhances the interaction with biological membranes, (ii) modifies or enhances interaction of CDs with hydrophobic drugs, and (iii) allows self-assembly of CDs, forming nanosized carriers and encapsulating drugs25,26. Polycationic CD nanoparticles containing siRNA have been recently used for the delivery of siRNA to the glomerular mesangium27.

Our group has published several studies demonstrating synthesis of amphiphilic CDs which were able self-assemble to form stable nanoparticles. Most of our amphiphilic derivatives have been prepared by modifying their primary face with hydrocarbon or perfluorocarbon lipophilic chains28–31. As demonstrated previously for a hydrophobic indeno[1,2-b]indole analog32, not only could these nanoparticles encapsulate this CK2 inhibitor but also released it in a controlled manner.

This study deals with the formation and anti-leukemic activity of iodinin-loaded nanoparticles made from amphiphilic α-CDs. Encapsulation efficiency and release profiles are reported and show the beneficial effect of the fluorinated amphiphilic α-CD derivatives. The non-toxicity of these derivatives on red blood cells confirmed their potential use for in vivo assays.

Experimental

General

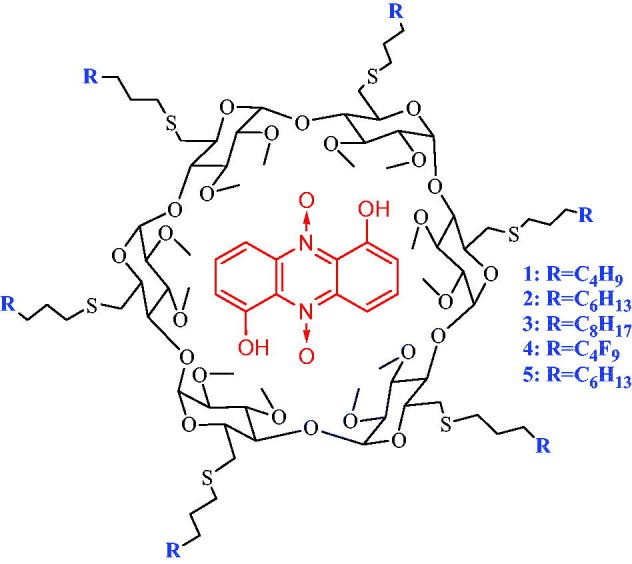

All chemical were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, La Jolla, CA, USA and were used without further purification. Native α-cyclodextrin was generously provided by Roquette Frères (Lestrem, France). Amphiphilic fluorinated α-CDs and their hydrocarbon analogues (Figure 2) were synthesised as previously described28,31. Briefly, after the selective protection of the primary hydroxyl groups with tertbutyldimethylsilyl groups, all the secondary hydroxyl groups were methylated using sodium hydride and methyl iodide. Removal of the tertbutyldimethylsilyl groups was performed with tetrabutylammonium fluoride in THF and introduction of the methanesulfonyl groups with methanesulfonyl chloride. Finally, the hydrophobic chains (fluorinated or hydrocarbonated) were introduced by nucleophilic substitution of the leaving groups by the thiolate derivate, generated in situ by the basic hydrolysis of the 3-perfluoroalkylpropane (or alkyl) isothiouronium salts using cesium carbonate. The structures and purities were confirmed using 1H and 13C NMR and mass spectroscopy analysis.

Figure 2.

Structure of inclusion complex of iodinin (red) in amphiphilic alkyl (1–3) or perfluoroalkyl (4,5) α-cyclodextrins.

Iodinin was isolated from batch cultures of the bacterium Streptosporangium sp. The bacterial mass culturing conditions, as well as the protocol for DMSO-extraction, subsequent HPLC-purification and identification of iodinin by MS and NMR were carried out as previously described19,22.

Dynamic light scattering measures were performed using a Zetasizer Nano ZSP instrument from Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK.

Preparation of nanoparticles by the highly loaded method

The iodinin loaded nanoparticles based α-CD were prepared by the nanoprecipitation technique, using a 0.8 × 10−4 M solution of preformed (1:1) iodinin:α-CD complexes overloaded with an additional amount of iodinin in the THF phase. The total concentration of iodinin was 1.6 × 10−4 M (iodinin/CD ratio = 2). The relevant solution of the preformed complex in THF (25 ml, 1 day stirring) was poured drop-wise into deionised water (50 ml) while stirring. A slightly turbid emulsion of nanospheres spontaneously formed. Solvent and a part of water were evaporated under reduced pressure and the total volume adjusted to 50 ml with water.

Particle size measurements

The mean particle size (diameter, nm) and the polydispersity index (PDI) of nanospheres were measured by dynamic light scattering using a NanoZS instrument, which analyses the fluctuations of scattered light intensity generated by diffusion of the particles in a diluted suspension (dynamic light scattering data are shown in Figures S1–S5 and Zeta potentials of empty and loaded nanoparticle dispersions are presented in Figures S6?S10). The measurements were carried out at 25 °C. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

Determination of the encapsulation efficiency

For measuring the loading efficiency, after the formation of nanoparticle suspensions by the highly loaded method, non-encapsulated iodinin in the nanoparticle dispersions was separated by centrifugation at 50,000 rpm for 1 h in order to settle down the loaded nanoparticles. The supernatant was removed. The precipitate was then lyophilised overnight, and the resulting powder containing the loaded nanoparticles was dissolved in a known amount of THF in order to obtain a clear solution. The absorbance of supernatant and THF solutions was analysed using an UV spectrophotometer at 289 nm to calculate the encapsulated drug quantity. Loading capacity was expressed in terms of associated drug percentage:

In vitro release studies

The suspensions of nanoparticles made from C6H13, C8H17 and C6F13 derivatives loaded with iodinin (1 ml of a 0.8 × 10−4 M solution) were introduced into a dialysis tube (cutoff 5000 Da) at 25 °C. This tube was then placed in a higher volume (20 ml) of phosphate buffered solution (pH 7.4) for a period of time. Same experiments have been done with non-encapsulated iodinin by using 1 ml of a 0.8 × 10−4 M iodinin THF/water solution. Aliquots of 1 ml of the buffered solution were removed at different time intervals to calculate the proportion of released and encapsulated molecules by UV spectrometry at 289 nm.

Cytotoxicity studies

The formulations were tested on the Brown Norwegian myeloid leukaemia (BNML) rat-derived AML cell line IPC-8133. The cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagles Medium (DMEM; Sigma, La Jolla, CA, USA) enriched with 10% horse serum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and added 100 IU/L penicillin and 100 mg/L streptomycin (both from Cambrex, Verviers, Belgium), and cultured in a humidified atmosphere (37 °C, 5% CO2). For cytotoxicity testing, the cells were seeded in 96 well tissue culture plates at 150,000 cells/mL. The cells were exposed to various concentrations of empty or iodinin-loaded nanoparticles for 24 h and then fixed in 2% buffered formaldehyde (pH 7.4) with the DNA-specific dye Hoechst 33342 (Polysciences Inc., Eppelheim, Germany) and scored for apoptosis as previously described34,35.

Results and discussion

α-CD nanoparticles

It has been reported that the highly loaded method was the most efficient for encapsulating hydrophobic compounds inside amphiphilic CD-based nanoparticles30. Since iodinin is hydrophobic, this method was chosen for its encapsulation, using THF as co-solvent which allowed the solubilisation of both iodinin and amphiphilic CD derivatives.

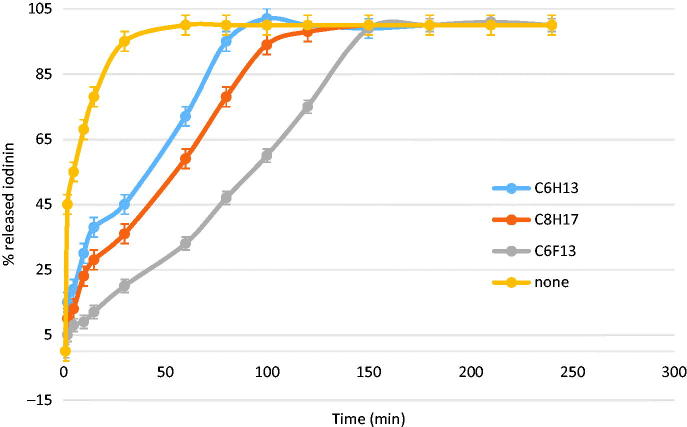

As shown in Table 1 and Figure 3, the different nanoparticles had similar sizes, ranging from 97.9 nm to 156.2 nm. Comparing 1/4 and 2/5, it was noticed that, for the same hydrophobic chain length, perfluorinated nanoparticles gave lower diameters than the hydrogenated ones. In fact, the specific properties of fluorous chains allowed for a more compact organisation of the hydrophobic chains inside the nanoparticles. Furthermore, for the same series (hydrogenated or fluorinated), it was an inverse relationship between the chain length and the size of the nanoparticle. It is also worth noting that empty nanoparticles had similar sizes as the loaded nanoparticles. All these data were found to match findings previously described in literature31,32.

Table 1.

Characteristics of loaded nanoparticles made from amphiphilic α-cyclodextrins.

| Derivative | Side chain | Nanoparticle size (nm) loaded/empty | Polydispersity index (PDI) loaded/empty | Associated drug (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | C4H9 | 159.3/162.3 | 0.07/0.04 | 40 |

| 2 | C6H13 | 117.0/126.3 | 0.10/0.13 | 54 |

| 3 | C8H17 | 104.1/105.8 | 0.11/0.05 | 58 |

| 4 | C4F9 | 109.7/120.7 | 0.02/0.25 | 36 |

| 5 | C6F13 | 097.9/90.6 | 0.08/0.10 | 62 |

Figure 3.

Sizes (in nm) of loaded nanoparticles and percentages of encapsulated iodinin for each derivative.

The experiments, run in triplicate, yielded particles with narrow size distribution (PDI <0.2) demonstrating high homogeneity of the nanoparticle suspensions.

The loading efficiency of iodinin in these various nanoparticles ranged from 36% to 62% for C4H9 and C6F13, respectively. Nevertheless, unlike what has been observed previously for acyclovir, nanospheres made from fluorinated α-CDs did not have significant impact on the encapsulation rate. The main differences were observed by varying the chain length (40%, 54% and 58% for C4H9, C6H13 and C8H17, respectively), suggesting that C8F17 would be slightly more efficient for encapsulation of iodinin.

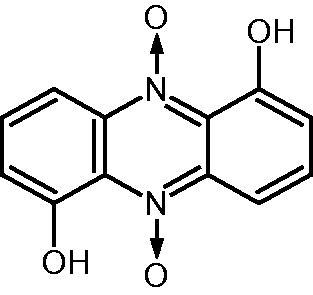

The controlled release studies was performed on suspensions having at least 50% encapsulated iodinin (i.e. C6H13, C8H17 and C6F13) in comparison with the profile obtained without any nanoparticles (a 0.8 × 10−4 M iodinin solution alone in THF/water solution). As shown in Figure 4, in the absence of nanospheres, the concentration equilibrium between the outside and inside compartments of the dialysis tube was obtained in less than 40 min.

Figure 4.

Release profiles of iodinin in phosphate buffered aqueous solution (pH 7.4).

The release profiles showed the positive effect of the nanoparticles on the controlled release (Figure 4). Iodinin release from highly loaded nanospheres reached completion within more than one hour for hydrocarbon amphiphilic α-CDs and between 2.5 and 3 h for the fluorinated nanospheres. After 1 h, 72% of the encapsulated iodinin were released from the C6H13 nanospheres versus only 30% from the fluorous analogue. It can be explained by the fact that fluorinated chains enhance intermolecular interactions inside the supramolecular assemblies compared to hydrogenated analogues, leading to more stable nanoparticles. These observations confirm previous studies which have showed that nanoparticles based on fluorinated compounds delayed acyclovir release, showing their potential for applications to drug delivery30.

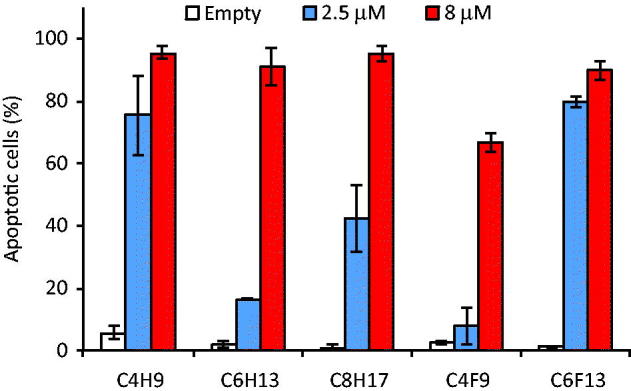

A particular point needs to be added about the toxicity of amphiphilic α-CDs. A recent study36 related a study of cytotoxicity on red blood cells. The results confirmed the potential of amphiphilic α-CDs to formulate bioactive molecules and then to be used for in vivo assays. We tested empty or iodinin-loaded fluorinated amphiphilic CD nanospheres for ability to induce cell death in the BNML-derived rat AML cell line IPC-81. This cell line produces AML with typical signs of the disease in xenograft mouse models, and responds to the benchmark AML drug daunorubicin in vitro and in vivo37. We found no toxicity towards the IPC-81 cells with the any of the empty nanoparticles (Figure 5). Iodinin-loaded nanoparticles, however, efficiently induced IPC-81 AML cell death within 24 h (Figure 5). From the different CD-compositions tested, we found that the C4H9 and C6F13 were the most potent formulation, whereas C6H13 and C4F9 were the least potent formulations. This is opposite to what was seen in the release studies, which showed that C6H13 released their cargo at a faster rate than C6F13 (Figure 4). This suggests that internalisation of the nanoparticles indeed play a role in the cytotoxic effect of the amphiphilic α-CD nanospheres. Although the efficacy of the nanospheres appeared lower than the original compound19,21, the encapsulation of iodinin is expected to lower toxic effects on non-target cells, thus increasing the therapeutic index for this potent AML-selective compound.

Figure 5.

Cytotoxicity of iodinin-loaded amphiphilic CD-nanospheres towards the AML cell line IPC-81. The cells were incubated with the different formulations for 24 h before assessment of cell death. The data are average of two separate experiments. The error bars indicate the two measurements.

Conclusions

This study describes the successful preparation of iodinin-loaded nanoparticles. The results indicate that nanoencapsulation of iodinin in α-CDs by the highly loaded method is possible, without any additional surface-active agent. With per-[6-desoxy-6–(3-perfluorohexylpropanethio)-2,3-di-O-methyl]-α-CD we were able to perform the most loaded nanoparticles (% of associated drug = 62) with a size of 97.9 nm. Tests of these nanoparticles on AML cells showed that they were efficient inducers of cell death, due to the encapsulated iodinin, since empty nanoparticles showed no adverse effects on the cells. Furthermore, amphiphilic α-CD derivatives could be functionalised on the secondary hydroxyl groups by targeting moieties such as folate38 or by incorporating the fragment antigen-binding (Fab) of a monoclonal antibody onto CDs to target IL-3 receptor α-chain (IL-3Rα, highly expressed on AML LSCs)24.

Supplementary Material

Funding Statement

The present work was supported by the “Partenariats Hubert Curien” (PHC) (Campus France, Programme Aurora, Grant Agreement No. 27460VC), by the Norwegian Research Council [Grant Agreement No. 213191/F11] and the Norwegian Cancer Society (Project no.: 4529447). Pr. Marc Le Borgne also thanks the “Institut français d’Oslo” for their support via the Åsgard Programme 2010. This scientific work was also supported by financial support from Rhône-Alpes region through an Explo’ra Sup scholarship (academic year 2012–2013).

Acknowledgements

Pr. Marc Le Borgne thanks Mr. Christophe Villard (Student Exchange Office of the Faculty of Pharmacy of Lyon) for his precious help. Dr. Florent Perret thanks Pr. Julien Leclaire for his financial help and Dr. Yves Chevalier from LAGEP laboratory for zeta sizer experiments. Pr. Stein O. Døskeland and Lars Herfindal thank Ing. Nina Lied Larsen for assistance with cell experiments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- 1.Laursen JB, Nielsen J.. Phenazine natural products: biosynthesis, synthetic analogues, and biological activity. Chem Rev 2004;104:1663–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdelfattah MS, Ishikawa N, Karmakar UK, et al. New phenazine analogues from Streptomyces sp. IFM 11694 with TRAIL resistance-overcoming activities. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 2016;69:446–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guttenberger N, Blankenfeldt W, Breinbauer R.. Recent developments in the isolation, biological function, biosynthesis, and synthesis of phenazine natural products. Bioorg Med Chem 2017;25:6149–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moorthy NS, Pratheepa V, Ramos MJ, et al. Fused aryl-phenazines: scaffold for the development of bioactive molecules. Curr Drug Targets 2014;15:681–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar S, Mujahid M, Verma AK.. Regioselective 6-endo-dig iodocyclization: an accessible approach for iodo-benzo[a]phenazines. Org Biomol Chem 2017;15:4686–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar S, Saunthwal RK, Mujahid M, et al. Palladium-catalyzed intramolecular Fujiwara-hydroarylation: synthesis of benzo[a]phenazines derivatives. J Org Chem 2016;81:9912–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garrison AT, Abouelhassan Y, Norwood VM 4th, et al. Structure–activity relationships of a diverse class of halogenated phenazines that targets persistent, antibiotic-tolerant bacterial biofilms and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Med Chem 2016;59:3808–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Udumula V, Endres JL, Harper CN, et al. Simple synthesis of endophenazine G and other phenazines and their evaluation as anti-methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus agents. Eur J Med Chem 2017;125:710–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xiong Z, Niu J, Liu H, et al. Synthesis and bioactivities of phenazine-1-carboxylic acid derivatives based on the modification of PCA carboxyl group. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2017;27:2010–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cimmino A, Evidente A, Mathieu V, et al. Phenazines and cancer. Nat Prod Rep 2012;29:487–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu Y, Yan Y, Wang L, et al. Design, facile synthesis and biological evaluations of novel pyrano[3,2-a]phenazine hybrid molecules as antitumor agents. Eur J Med Chem 2017;127:928–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis JG.Chromobacterium iodinum (n. sp.). Zentralbl Bakteriol Parasitenkd Infektionskr Hyg, II Abt 1939;100:273–6. [Google Scholar]

- 13.McIlwain H.The anti-streptococcal action of iodinin. Naphthaquinones and anthraquinones as its main natural antagonists. Biochem J 1943;37:265–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Podojil M, Gerber NN.. The biosynthesis of 1,6-phenazinediol 5,10-dioxide (iodinin) by Brevibacterium iodinum. Biochemistry 1967;6:2701–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Byng GS, Turner JM.. Isolation of pigmentation mutants of Pseudomonas phenazinium. J Gen Microbiol 1976;97:57–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hiroshi T, Takashi S, Masaru I, et al. Intracellular accumulation of phenazine antibiotics produced by an alkalophilic actinomycete. I. Taxonomy, isolation and identification of the phenazine antibiotics. Agric Biol Chem 1988;52:301–6. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cesková P, Zák Z, Johnson DB, et al. Formation of iodinin by a strain of Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans grown on elemental sulfur. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 2002;47:78–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maskey PR, Li F, Qin S, et al. Chandrananimycins A approximately C: production of novel anticancer antibiotics from a marine Actinomadura sp. isolate M048 by variation of medium composition and growth. J Antibiot 2003;56:622–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Myhren LE, Nygaard G, Gausdal G, et al. Iodinin (1,6-dihydroxyphenazine 5,10-dioxide) from Streptosporangium sp. induces apoptosis selectively in myeloid leukemia cell lines and patient cells. Mar Drugs 2013;11:332–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bilal M, Guo S, Iqbal HMN, et al. Engineering pseudomonas for phenazine biosynthesis, regulation, and biotechnological applications: a review. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2017;33:191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Viktorsson EÖ, Melling Grøthe B, Aesoy R, et al. Total synthesis and antileukemic evaluations of the phenazine 5,10-dioxide natural products iodinin, myxin and their derivatives. Bioorg Med Chem 2017;25:2285–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sletta H, Degnes KF, Herfindal L, et al. Anti-microbial and cytotoxic 1,6-dihydroxyphenazine-5,10-dioxide (iodinin) produced by Streptosporangium sp. DSM 45942 isolated from the fjord sediment. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2014;98:603–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sallas F, Darcy R.. Amphiphilic cyclodextrins – advances in synthesis and supramolecular chemistry. Eur J Org Chem 2008;2008:957–69. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo J, Russell EG, Darcy R, et al. Antibody-targeted cyclodextrin-based nanoparticles for siRNA delivery in the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia: physicochemical characteristics, in vitro mechanistic studies, and ex vivo patient derived therapeutic efficacy. Mol Pharmaceutics 2017;14:940–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Erdogar N, Varan G, Bilensoy E.. Amphiphilic cyclodextrin derivatives for targeted drug delivery to tumors. Curr Top Med Chem 2017;17:1521–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Erdogar N, Iskit AB, Eroglu H, et al. Antitumor efficacy of bacillus calmette-guerin loaded cationic nanoparticles for intravesical immunotherapy of bladder tumor induced rat model. J Nanosci Nanotechnol 2015;15:10156–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zuckerman JE, Gale A, Wu P, et al. siRNA delivery to the glomerular mesangium using polycationic cyclodextrin nanoparticles containing siRNA. Nucleic Acid Ther 2015;25:53–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghera BB, Perret F, Baudouin A, et al. Synthesis and characterization of O-6-alkylthio- and perfluoroalkylpropanethio-α-cyclodextrins and their O-2-, O-3-methylated analogues. New J Chem 2007;31:1899–906. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bertino-Ghera B, Perret F, Fenet B, Parrot-Lopez H.. Control of the regioselectivity for new fluorinated amphiphilic cyclodextrins: synthesis of di- and tetra(6-deoxy-6-alkylthio)- and 6-(perfluoroalkylpropanethio)-α-cyclodextrin derivatives. J Org Chem 2008;73:7317–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghera BB, Perret F, Chevalier Y, Parrot-Lopez H. Novel nanoparticles made from amphiphilic perfluoroalkyl alpha-cyclodextrin derivatives: preparation, characterization and application to the transport of acyclovir. Int J Pharm 2009;375:155–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perret F, Duffour M, Chevalier Y, Parrot-Lopez H.. Design, synthesis, and in vitro evaluation of new amphiphilic cyclodextrin-based nanoparticles for the incorporation and controlled release of acyclovir. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2013;83:25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perret F, Marminon C, Zeinyeh W, et al. Preparation and characterization of CK2 inhibitor-loaded cyclodextrin nanoparticles for drug delivery. Int J Pharm 2013;441:491–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lacaze N, Gombaud-Saintonge G, Lanotte M.. Conditions controlling long-term proliferation of Brown Norway rat promyelocytic leukemia in vitro: primary growth stimulation by microenvironment and establishment of an autonomous Brown Norway ‘leukemic stem cell line’. Leuk Res 1983;7:145–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bøe R, Gjertsen BT, Vintermyr OK, et al. The protein phosphatase inhibitor okadaic acid induces morphological changes typical of apoptosis in mammalian cells. Exp Cell Res 1991;195:237–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oftedal L, Selheim F, Wahlsten M, et al. Marine benthic cyanobacteria contain apoptosis-inducing activity synergizing with daunorubicin to kill leukemia cells, but not cardiomyocytes. Mar Drugs 2010;8:2659–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Róka E, Ujhelyi Z, Deli M, et al. Evaluation of the cytotoxicity of α-cyclodextrin derivatives on the caco-2 cell line and human erythrocytes. Molecules 2015;20:20269–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gausdal G, Gjertsen BT, McCormack E.. Abolition of stress-induced protein synthesis sensitizes leukemia cells to anthracycline-induced death. Blood 2008;111:2866–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Erdogar N, Esendagli G, Nielsen T, et al. From therapeutic efficacy of folate receptor-targeted amphiphilic cyclodextrin nanoparticles as a novel vehicle for paclitaxel delivery in breast cancer. J Drug Target 2018;26:66–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.