Abstract

Cannabinoid (CB) and opioid systems are both involved in analgesia, food intake, mood and behavior. Due to the co-localization of µ-opioid (MOR) and CB1 receptors in various regions of the central nervous system (CNS) and their ability to form heterodimers, bivalent ligands targeting to both these systems may be good candidates to investigate the existence of possible cross-talking or synergistic effects, also at sub-effective doses. In this work, we selected from a small series of new Rimonabant analogs one CB1R reverse agonist to be conjugated to the opioid fragment Tyr-D-Ala-Gly-Phe-NH2. The bivalent compound (9) has been used for in vitro binding assays, for in vivo antinociception models and in vitro hypothalamic perfusion test, to evaluate the neurotransmitters release.

Keywords: Cannabinoid receptor CB1R, Rimonabant, opioids, bivalent ligand, pain

Introduction

Cannabinoid and opioid receptors are expressed mostly in the same CNS areas, and both are involved in the control of analgesia, food intake, mood and behavior. In the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, the µ-opioid receptor MOR and CB1R are co-localized at the same neurons, also at the supra-spinal level, such as the periaqueductal gray (PAG), the raphe nuclei and the central-medial thalamic nuclei1.

According to the several cell line studies where the MOR and CBR1 are endogenously co-expressed, they share cAMP signaling pathways, even though they may use different sets of G-proteins2.

Studies on opioid and CB1R knock-out mice, demonstrated that their density and activity strongly depend on each other3 , 4. Also, preclinical and clinical studies stated that the interaction between the opioid and cannabinoid systems can lead to promising therapeutic applications in pain control and in alimentary disorders management5–8. Thus, bivalent ligands binding to CB1R and MOR simultaneously may result in new potent analgesic agents. Recently, Le Naour et al.6 proposed a bivalent approach to target both MOR and CB1R, connecting a selective MOR agonist to a CB1R selective inverse agonist, via a spacer group of varied length.

One of the synthesized compounds showed an extremely potent activity in in vivo antinociceptive tests and was devoid of tolerance. Additive or synergic interactions between opioid and cannabinoid systems in producing analgesia have been previously described and reviewed in detail9 , 10. Morphine-induced antinociception is completely reversed by the CB1R antagonist AM25111, and tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)-induced antinociception is blocked by naloxone12.

The cross-tolerance between THC and morphine and the possibility that these receptors interact pharmacologically were demonstrated by naloxone or CB1R antagonist. Synergism between cannabinoids and opioids at sub-effective doses has also been reported13 , 14. Additionally, co-administration of morphine with a CB1R antagonist inhibited the development of both acute and chronic tolerance to morphine15.

Other evidence for interaction was obtained from self-administration studies showing that both receptors are involved in reward processes. In this regard, both CB1R antagonist (SR 141716)16, and opioid antagonist naloxone decreased self-administration of morphine or Δ9-THC17. In mice lacking µ (MOR) and δ (DOR) opioid receptors, the cannabinoid withdrawal syndrome is reduced18.

According to our research line based on the design of multitarget compounds19 , 20, the present study represents a starting point to develop bivalent ligands as pharmacologic tools to investigate the MOR–CB1R mutual interactions. The bivalent ligand designed for this purpose consists of a selective µ-receptor peptide agonist connected to a CB1R selective inverse agonist fused together21.

The novel compound was extensively tested for in vitro binding, GTP stimulation, neurotransmitters release and antinociceptive in vivo activity. The design rationale for targeting MOR and CB1R simultaneously is based on previous studies with bivalent ligands6. The MOR agonist pharmacophore derived from the opioid peptide biphalin, was previously employed in the design of several bivalent compounds, due to its property to well tolerate the connection at the C-terminus with another pharmacophore22 , 23 , 19.

Since other authors show that a CB1R inverse agonist is capable of eliminating morphine tolerance and dependence24 , 25, we selected compound 5 (Scheme 1) with CB1R inverse agonist activity as CB1R pharmacophore (Figure 1), in analogy with the work by Le Naour et al.6

Scheme 1.

Synthesized Rimonabant analogs.

Figure 1.

Structure of bivalent compounds previously designed by Le Naour et al.6

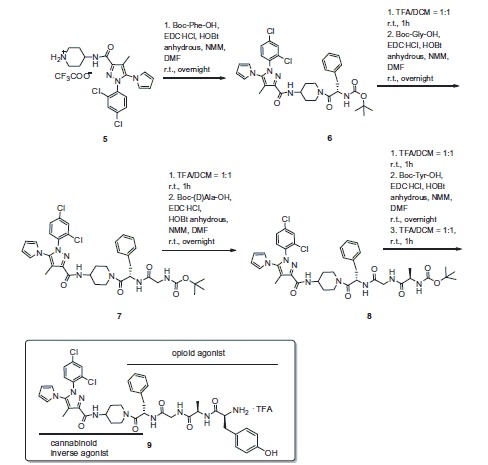

Thus, the bivalent ligand 9 was synthesized following the “fused-bivalent approach”21, with the expectation that the resulting product would be capable to interact at CB1R, MOR and CB1R–MOR heterodimer form. The bivalent compound was prepared by coupling each Boc-protected amino acid of the opioid peptide sequence to the secondary amine of 4-aminopiperidine group present in the structure of Rimonabant analog 5.

The opioid fragment Tyr-D-Ala-Gly-Phe-NH2 (10) was used as reference compound for opioid activity on MOR and DOR19.

Results and discussion

A series of novel 1-aryl-5-(1H-pyrrol-1-yl)-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxamides Rimonabant analogs were tested for the stimulation of G protein to evaluate their inverse agonist activity at CB1R to develop a bivalent compound (Scheme 1).

Compounds 1 and 2 have been previously synthesized and characterized by Silvestri et al.26 for the development of potent CBR1 inverse agonists. The molecules were designed by pursuing a bioisosteric approach on Rimonabant, from which 5 resulted to be one of the most interesting candidate with the advantage to be easily derivatisable by coupling with an opioid peptide on the piperidine secondary nitrogen in place of the tert-butoxycarbonyl (Boc) group. Indeed N-Boc derivative 3 resulted to be active, showing that the substitution of a bulky moiety at the secondary nitrogen of the 4-aminopiperidine terminus was possible without any loss of activity. Firstly, we investigated the cannabinoid receptor (CBR) binding affinity of the Rimonabant analogs compared with Rimonabant in competition binding assays using the nonselective cannabinoid receptor radioligand [ 3H]WIN55 212 (CB1R < CB2R) (Figure 2). In this test, the Rimonabant analogs 1–4 exhibited nanomolar Ki values: compounds 1 (Ki =125.9 nM) and 3 (Ki =192.9 nM) were the most potent derivatives as compared with Rimonabant (Ki =25 nM) (Table S1, see SI)27 , 28.

Figure 2.

The binding affinity of Rimonabant and its analogs on CBR (A) and the MOR (B), DOR (C), KOR (D) and CBR binding affinity of 5, 9 and 10 (Tyr-D-Ala-Gly-Phe-NH2) (E) in competition binding experiments. Figures represent the specific binding of [3H]WIN55 212–2, [3H]DAMGO, [3H]IleDelt II and [3H]HS665 in percentage in the presence of increasing concentrations (10 −11–10−5 M) of the indicated unlabeled ligands performed in rat (A, B and E) or in guinea pig (D) whole brain membrane homogenates. “Total” on the x-axis indicates the total specific binding of radioligand, which is measured in the absence of the unlabeled compounds. The level of total specific binding was defined as 100% and is presented with a dotted line. Points represent means ± SEM for at least three experiments performed in duplicates.

In the following step, we investigated the effect of Rimonabant and its analogs on G-protein activity. In these experiments, we determined their agonist, antagonist or inverse agonist nature. The experiments were performed by [35S]GTPγS binding assays to control the GDP to GTP exchange of the α-subunit of Gi-protein. The analogs 1, 2, 3 and 4 decreased [35S]GTPγS specific binding (thus G-protein activity) compared with basal activity by more than 80% (Emax = 17.5). Compounds 1–4 showed strong reduction of G-protein activity comparable to Rimonabant29–31 and therefore displayed inverse agonist effects (Table 1). We examined the opioid receptor binding affinity of 5 in competition binding experiments, using opioid receptor selective radioligands. As expected, 5 did not bind to MOR and DOR and the affinity for the KOR was negligible (Table 1S, Figure 2(B–D))31–37.

Table 1.

The maximal G-protein efficacy (Emax) and ligand potency (logEC50) of the Rimonabant and its analogs 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, bivalent compound 9 and opioid peptide 10 in [35S]GTPγS binding assays on rat brain membrane homogenates. The values were calculated according to dose–response curves in Figure S1 (see SI) as described in the “Data analysis” section.

| Emax ± S.E.M. (%) | LogEC50 ± S.E.M. (EC50) | |

|---|---|---|

| Rimonabant | 17.5 ± 5.72 | −5.65 ± 0.12 (2.2 μM) |

| 1 | 26 ± 5.27 | −5.78 ± 0.11 (1.62 μM) |

| 2 | 22.95 ± 4.3 | −5.81 ± 0.09 (1.54 μM) |

| 3 | 12.78 ± 8.48 | −5.57 ± 0.15 (2.69 μM) |

| 4 | 55.95 ± 8.44 | −5.72 ± 0.3 (1.87 μM) |

| 5 | 99.2 ± 46.1 | ambiguous* |

| Bivalent compound (9) | 36.62 ± 10.35 | −5.44 ± 0.21 (3.6 μM) |

| Tyr-D-Ala-Gly-Phe-NH2 (10) | 161.5 ± 4.08 | −7.09 ± 0.22 (81.3 nM) |

Since the compound did not alter significantly the total specific binding of the radioligand, thus logEC50 values cannot be interpreted.

Opioid fragment 10 displayed a high affinity for MOR and DOR (MOR > DOR), while the compound had modest affinity for KOR, even at high nanomolar concentration (Table S1). As expected, the opioid peptide fragment did not show any affinity for CBR1 (Table 1S, Figure 2(E)); it increased G-protein activity with a maximum efficacy (Emax) of nearly 70% above basal activity with EC50 of 81.3 nM, thus we can assert that this compound behaved as an agonist.

In the second part of our work, the designed bivalent compound 9 was synthesized (Scheme 2) and fully characterized (see SI). Peptide 10 has been prepared following the standard synthetic procedure for coupling reactions19.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of bivalent compound 9.

Compound 9 behaved as inverse agonist as it decreased [35S]GTPγS specific binding, thus reducing G-protein activity compared with the basal level (Table 1). Attaching the opioid fragment to Rimonabant analog 5 to give the bivalent compound 9 resulted in a rather selective DOR ligand with an unexpected improvement of affinity for KOR, and a loss in affinity for MOR and DOR, as compared with the opioid fragment alone (Table S1, Figure 2(B–D)). According to the affinities displayed by the opioid peptide 10 and 5, the bivalent compound 9 showed modest affinity towards CB1R (Table S1, Figure 2(E)).

The results obtained in the hot plate and tail flick tests after i.c.v. injection in mice, are reported in Figure 3. In these experiments, compound 9 was administered i.c.v. at doses of 1, 5 and 10 µg/mouse. Neither in the hot plate nor in the tail flick test treatments modified the behavioral response to thermal nociceptive stimuli. In the hot plate test, two-way ANOVA revealed no difference in treatments [F 3,120 = 2.65, p = 0.522] and in time [F 4,120 = 2.30, p = 0.0629] paradigms. Similar absence of effect was observed in the tail flick test, since treatment [F 3,120 = 2.6, p = 0.0551] did not affect the latency of the nociceptive response all over the time [F 4,120 = 1.32, p = 0.2649].

Figure 3.

Hot-plate and Tail flick test. In these experiments, compound 9 (C9) was administered i.c.v. at doses of 1, 5 and 10 μg/mouse. V is for vehicle. N = 10.

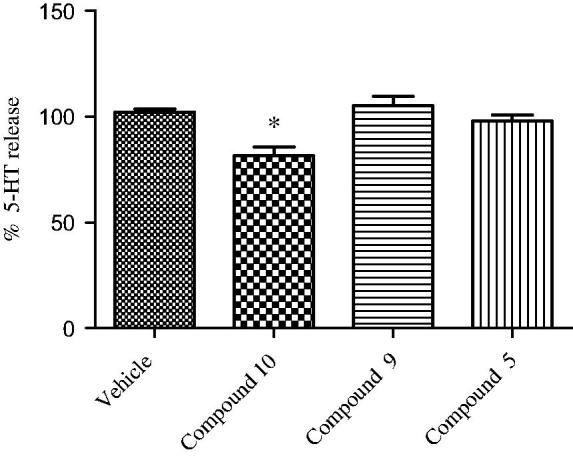

To further explore the pharmacologic profile of the bivalent ligand, hypothalamic perfusion test was performed with the aim to compare the release of hypothalamic neurotransmitters, after administration of the two separate pharmacophores and compound 9 in the preparation of synaptosomes. In this experiment, the three combinations produced different effects, showing a possible influence of the contemporary stimulation of CBRs and opioid systems on neurotransmitters release. As regards to 10, we found a significant stimulatory effect on norepinephrine (NE) and an inhibitory effect on serotonin (5-HT) and dopamine (DA) release, from hypothalamic synaptosomes (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 4.

Effect of opioid peptide 10 , bivalent compound 9 and 5 on NE and DA release from hypothalamic synaptosomes, in vitro. ANOVA p < 0.0001, ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01 vs. vehicle.

Figure 5.

Effect of opioid peptide 10, bivalent compound 9 and 5 on 5-HT release from hypothalamic synaptosomes, in vitro. ANOVA p < 0.05, *p < 0.05 vs. vehicle.

Administration of compound 5 decreased only the DA release, whereas the treatment with 9 resulted in the reduction of the NE release’s stimulation and DA inhibition (in less extent), with no significant effects on the 5-HT release. This is consistent with the inverse agonist activity on the G-protein system of compound 9. The significant stimulatory effect on NE release could indicate a possible involvement in the regulation of energy balance. By contrast, the reduced inhibitory effect on hypothalamic DA release, compared with both parent molecules, is coherent with a minor potential of behavioral adverse effects in vivo 38 , 39.

The modulatory effects on hypothalamic biogenic amines suggest a possible involvement of both 10 and 5 in the interconnected neuronal pathways for the energy balance control. 5-HT release plays an anorectic role in the hypothalamus40; DA injection in the perifornical hypothalamus inhibited food intake41, while DA administration in the lateral hypothalamus stimulated feeding42. NE could also exert both anorexigenic and orexigenic effects, related to the activation of α1- and α2-adrenoceptors, respectively43. In addition, NE binding to hypothalamic α2-adrenoceptors could increase energy expenditure, through the stimulated sympathetic activity44. Previously, we observed that endomorphin-2 (EM-2), a selective MOR agonist, was able to stimulate food intake45. The orexigenic effect was, albeit partially, related to the stimulated hypothalamic DA and NE activity which is also consistent with the increased oxygen consumption induced by EM-2 administration to mice46.

The Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion and Toxicity (ADMET) properties of compounds 5, 9 and 10 were assessed by means of web servers and specialized programs. Several tools are available to profile compounds ADMET properties using in silico calculations. In Tables 2S–4S are reported the admetSAR47, Molinspiration and cbligand.org ADMET calculated properties. In general, compounds 5, 9 and 10 are not substrate for cytochromes and present low toxicity profiles (Table 2).

Table 2.

AdmetSAR regression derived data for diverse chemicals associated with known ADMET profiles for compounds 5, 9 and 10.

| Model | Unit | 5 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption | Aqueous solubility | LogS | −3.0087 | −3.1063 | −3.3561 |

| Caco-2 permeability | LogPapp, cm/s | 0.4939 | 0.1530 | −0.2667 | |

| Toxicity | Rat acute toxicity | LD50, mol/kg | 2.6224 | 2.6993 | 2.2387 |

| Fish toxicity | pLC50, mg/L | 1.6053 | 1.3864 | 1.6515 | |

| Tetrahymena pyriformis toxicity | pIGC50, μg/L | 0.5156 | 0.4875 | −0.1386 |

Regarding adsorption, derivative 9 violates three Lipinski’s rules (high MW, number of HB donators and acceptors) that could prevent its oral bioavailability. AdmetSAR BBB and CACO predicted permeability indicate compound 5 as likely permeable, while compounds 9 and 10 are predicted at low probability to permeate BBB and CACO cells. These values are somehow in agreement with those reported in Table 4S where eight QSAR models indicate 5 as fully able to penetrate BBB, while 9 and 10 are predicted on the edge among positive and negative BBB penetrating molecules, as evinced from plots and threshold values reported in Table 5S.

To further inspect on possible BBB permeability, new models were herein developed by means of the python programming language, open-source cheminformatics library rdkit (www.rdkit.org), mathematical and scientific libraries numpy and scipy, machine-learning library scikit-learn48. Application of the two new models confirmed that compound 5 is able to penetrate BBB, while compounds 9 and 10, although predicted not able to penetrate BBB, show some probability to cross the BBB. The graphical analyses of similarity maps (Figure 2S) indicate the molecular portions likely responsible for the positive/negative BBB penetration49.

According to our experiments, we can conclude that the receptor binding profile and biological activity of the bivalent compound 9 significantly changed compared with the individual components. The bivalent compound 9 showed higher selectivity for MOR than the enkephalin-like opioid peptide fragment 10. More interestingly, it showed an improved KOR affinity compared with 5 and 10. The stimulation of the G-protein system could be explained by the inverse agonist effect of the bivalent compound. The lack of antinociceptive effect deals with the biological profile of an inverse agonist triggering the G-protein cascade. Also the ADMET properties of 9 are critical and establish benchmarks for further development of this class of bivalent compounds. Further studies on an alternative design of novel bivalent compounds based on an opioid peptide and a Rimonabant analog are currently undergoing in our laboratory.

Supplementary Material

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

Funding

The binding experiments were supported by National Research Development and Innovation Office (NKFIH) [grant number OTKA 108518] and by the ÚNKP-ÚNKP-16-3 New National Excellence Program of the Ministry of human capacities (Hungary).

References

- 1. Zador F, Wollemann M. Receptome: interactions between three pain related receptors or the Triumvirate of cannabinoid, opioid and TRPV1 receptors . Pharmacol Res 2015;102:254–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shapira M, Vogel Z, Sarne Y.. Opioid and cannabinoid receptors share a common pool of GTP-binding proteins in cotransfected cells, but not in cells which endogenously coexpress the receptors. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2000;20:291–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Berrendero F, Mendizabal V, Murtra P, et al. Cannabinoid receptor and WIN 55 212-2-stimulated [35S]-GTPgammaS binding in the brain of mu-, delta- and kappa-opioid receptor knockout mice. Eur J Neurosci 2003;18:2197–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Uriguen L, Berrendero F, Ledent C, et al. Kappa- and delta-opioid receptor functional activities are increased in the caudate putamen of cannabinoid CB1 receptor knockout mice . Eur J Neurosci 2005;22:2106–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jagerovic N, Fernandez-Fernandez C, Erdozain AM, et al. Combining rimonabant and fentanyl in a single entity: preparation and pharmacological results. Drug Des Dev Ther 2014;8:263–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Le Naour M, Akgun E, Yekkirala A, et al. Bivalent ligands that target µ-opioid (MOP) and cannabinoid1 (CB1) receptors are potent analgesics devoid of tolerance. J Med Chem 2013;56:5505–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Poras H, Bonnard E, Dange E, et al. New orally active dual enkephalinase inhibitors (DENKIs) for central and peripheral pain treatment. J Med Chem 2014;57:5748–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cota D, Tschop MH, Horvath TL, Levine AS.. Cannabinoids, opioids and eating behavior: the molecular face of hedonism?. Brain Res Rev 2006;51:85–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Desroches J, Beaulieu P.. Opioids and cannabinoids interactions: involvement in pain management. Curr Drug Targets 2010;11:462–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bushlin I, Rozenfeld R, Devi LA.. Cannabinoid-opioid interactions during neuropathic pain and analgesia. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2010;10:80–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. da Fonseca Pacheco D, Klein A, de Castro Perez A, et al. The µ-opioid receptor agonist morphine, but not agonists at δ- or k-opioid receptors, induces peripheral antinociception mediated by cannabinoid receptors. Br J Pharmacol 2008;154:1143–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Manzanares J, Corchero J, Romero J, et al. Pharmacological and biochemical interactions between opioids and cannabinoids. Trends Pharmacol Sci 1999;20:287–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wollemann M, Toth F, Benyhe S. Protein kinase C inhibitor BIM suspended TRPV1 effect on mu-opioid receptor. Brain Res Bull 2013;90:114–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Parolaro D, Rubino T, Vigano D, et al. Cellular mechanisms underlying the interaction between cannabinoid and opioid system. Curr Drug Targets 2010;11:393–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Manzanares J, Ortiz S, Oliva JM, et al. Interactions between cannabinoid and opioid receptor systems in the mediation of ethanol effects. Alcohol Alcohol 2005;40:25–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Scavone JL, Sterling RC, Van Bockstaele EJ.. Cannabinoid and opioid interactions: implications for opiate dependence and withdrawal. Neuroscience 2013;248:637–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Befort K. Interactions of the opioid and cannabinoid systems in reward: insights from knockout studies. Front Pharmacol 2015;56:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moreira FA, Aguiar DC, Campos AC, et al. Antiaversive effects of cannabinoids: is the periaqueductal gray involved? Neural Plast 2009;2009:625469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mollica A, Costante R, Novellino E, et al. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of two opioid agonist and Cav 2.2 blocker multitarget ligands. Chem Biol Drug Des 2015;86:156–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Monti L, Stefanucci A, Pieretti S, et al. Evaluation of the analgesic effect of 4-anilidopiperidine scaffold containing ureas and carbamates. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem 2016;31:1638–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dvoracsko S, Stefanucci A, Novellino E, Mollica A.. The design of multitarget ligands for chronic and neuropathic pain. Future Med Chem 2015;7:2469–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Podolsky AT, Sandweiss A, Hu J, et al. Novel fentanyl-based dual µ/δ-opioid agonists for the treatment of acute and chronic pain. Life Sci 2013;93:1010–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Deekonda S, Wugalter L, Rankin D, et al. Design and synthesis of novel bivalent ligands (MOR and DOR) by conjugation of enkephalin analogues with 4-anilidopiperidine derivatives. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2015;25:4683–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Caille S, Parsons LH.. Cannabinoid modulation of opiate reinforcement through the ventral striatopallidal pathway. Neuropsychopharmacology 2006;31:804–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Azizi P, Haghparast A, Hassanpour-Ezatti M.. Effects of CB1 receptor antagonist within the nucleus accumbens on the acquisition and expression of morphine-induced conditioned place preference in morphine-sensitized rats. Behav Brain Res 2009;197:119–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Silvestri R, Cascio MG, La Regina G, et al. Synthesis, cannabinoid receptor affinity, and molecular modeling studies of substituted 1-aryl-5-(1H-pyrrol-1-yl)-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxamides. J Med Chem 2008;51:1560–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rinaldi-Carmona M, Barth F, Héaulme M.. Biochemical and pharmacological characterisation of SR141716A, the first potent and selective brain cannabinoid receptor antagonist. Life Sci 1995;56:1941–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rinaldi-Carmona M, Barth F, Héaulme M, et al. SR141716A, a potent and selective antagonist of the brain cannabinoid receptor. FEBS Lett 1994;350:240–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. MacLennan SJ, Reynen PH, Kwan J, Bonhaus DW.. Evidence for inverse agonism of SR141716A at human recombinant cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptors. Br J Pharmacol 1998;124:619–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sim-Selley LJ, Brunk LK, Selley DE.. Inhibitory effects of SR141716A on G-protein activation in rat brain. Eur J Pharmacol 2001;414:135–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cinar R, Szücs M.. CB1 receptor-independent actions of SR141716 on G-protein signaling: coapplication with the µ-opioid agonist Tyr-D-Ala-Gly-(NMe)Phe-Gly-ol unmasks novel, pertussis toxin-insensitive opioid signaling in µ-opioid receptor-Chinese hamster ovary cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2009;330:567–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fong TM, Shearman LP, Stribling DS, et al. Pharmacological efficacy and safety profile of taranabant in preclinical species. Drug Dev Res 2009;70:349–62. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kathmann M, Flau K, Redmer A, et al. Cannabidiol is an allosteric modulator at mu- and delta-opioid receptors . Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2006;372:354–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Seely KA, Brents LK, Franks LN, et al. AM-251 and rimonabant act as direct antagonists at µ-opioid receptors: implications for opioid/cannabinoid interaction studies. Neuropharmacology 2012;63:905–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zádor F, Kocsis D, Borsodi A, Benyhe S. Micromolar concentrations of rimonabant directly inhibits delta opioid receptor specific ligand binding and agonist-induced G-protein activity. Neurochem Int 2014;67:14–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zádor F, Lénárt N, Csibrány B, et al. Low dosage of rimonabant leads to anxiolytic-like behavior via inhibiting expression levels and G-protein activity of kappa opioid receptors in a cannabinoid receptor independent manner. Neuropharmacology 2015;89:298–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zádor F, Otvös F, Benyhe S, et al. Inhibition of forebrain µ-opioid receptor signaling by low concentrations of rimonabant does not require cannabinoid receptors and directly involves µ-opioid receptors. Neurochem Int 2012;61:378–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Deats SP, Adidharma W, Yan L.. Hypothalamic dopaminergic neurons in an animal model of seasonal affective disorder. Neurosci Lett 2015;602:17–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nathan PJ, O’Neill BV, Napolitano A, Bullmore ET.. Neuropsychiatric adverse effects of centrally acting antiobesity drugs. CNS Neurosci Ther 2011;17:490–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Leibowitz SF. Hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus: interaction between alpha 2-noradrenergic system and circulating hormones and nutrients in relation to energy balance. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 1988;12:101–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gillard ER, Dang DQ, Stanley BG.. Evidence that neuropeptide Y and dopamine in the perifornical hypothalamus interact antagonistically in the control of food intake. Brain Res 1993;628:128–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yang ZJ, Meguid MM. LHA dopaminergic activity in obese and lean Zucker rats. NeuroReport 1995;6:1191–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wellman PJ, Davies BT, Morien A, McMahon L.. Modulation of feeding by hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus α1- and α2-adrenergic receptors. Life Sci 1993;53:669–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Levin BE. Reduced paraventricular nucleus norepinephrine responsiveness in obesity-prone rats. Am J Physiol 1996;270:456–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Brunetti L, Ferrante C, Orlando G, et al. Orexigenic effects of endomorphin-2 (EM-2) related to decreased CRH gene expression and increased dopamine and norepinephrine activity in the hypothalamus. Peptides 2013;48:83–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Asakawa A, Inui A, Ueno N, et al. Endomorphin-1, an endogenous mu-opioisd receptor-selective agonist, stimulates oxygen consumption in mice. Horm Metab Res 2000;32:51–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cheng F, Li W, Zhou Y, et al. AdmetSAR: a comprehensive source and free tool for assessment of chemical ADMET properties. J Chem Inf Model 2012;52:3099–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Duchesnay D. Scikit-learn: machine learning in Python. J Mach Learn Res 2011;12:2825–30. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Riniker S, Landrum GA.. Similarity maps – a visualization strategy for molecular fingerprints and machine-learning methods. J Cheminform 2013;5:43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.