Abstract

Background

Health disparities continue to persist among Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander (NHPI) communities.

Objectives

This study sought to understand the perspectives of community organizations in the Ulu Network on how researchers can collaborate with communities to promote community wellness.

Methods

Key informant interviews and small group interviews were conducted with the leadership in the Ulu Network.

Results

Five themes were identified that highlight the importance of investing time and commitment to build authentic relationships, understanding the diversity and unique differences across Pacific communities, ensuring that communities receive direct and meaningful benefits, understanding the organizational capacity, and initiating the dialog early to ensure that community perspectives are integrated in every stage of research.

Conclusions

Increasing capacity of researchers, as well as community organizations, can help build toward a more equitable and meaningful partnership to enhance community wellness.

Keywords: Pacific, community–university partnerships, capacity building, community-based participatory research, minority health, translational research, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander

Community leaders, funders, policymakers, and academic researchers have recognized that conventional research approaches have not shown effective results with sustainable impact to address persistent issues in diverse cultures and minority communities.1–3 As a result, new models of research have emerged highlighting the potential of community-engaged research and the need to build the capacity among researchers to engage respectfully, ethically, and meaningfully with communities.4–8 Gaining a better understanding of how researcher capacity can be enhanced from community perspectives may help in more effectively addressing health disparities in minority communities.9,10

NHPI represent a culturally diverse range of minority communities across the Pacific, including Native Hawaiians, Samoans, Tongans, Guamanians/Chamorro, Micronesians, and Fijians.11 Western countries’ first contact with many of the Pacific Islands occurred during the research voyages of late 18th century, when it was observed that Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Peoples were healthy and robust people.12 With this first contact began irreversible changes including decimation of the populations by introduced infectious diseases, and social, economic, and political domination and colonization by Western countries. The loss of land and cultural practices, drastic changes in dietary patterns, and the lack of access to educational and socioeconomic opportunities that are connected with NHPI cultural values13–16 continues to contribute to health disparities that are among the worst in the nation.17–20 Unethical research in these communities includes the well-documented experimentation done without consent to Hansen’s disease patients in Kalaupapa, Hawai‘i21 and nuclear bomb testing on an inhabited Pacific Ocean atoll.22 These studies, as well as other less known research, have led to exploitation and harmful stereotyping, compounding suspicion among community members toward the research enterprise.23–25

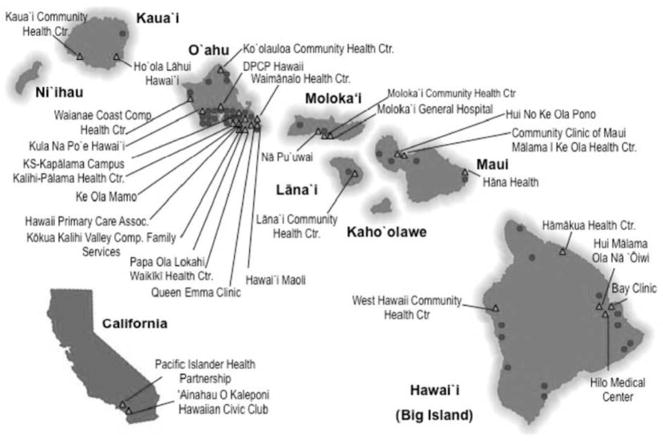

Innovative practices and collaborations have formed over the past decade to build community–university alliances to address health disparities among NHPI communities in Hawai‘i and throughout the Pacific region.8,26–31 One such example is the Ulu Network, a community coalition formed in 2003 by The Center for Native and Pacific Health Disparities Research (The Center) at the University of Hawai‘i, John A. Burns School of Medicine’s Department of Native Hawaiian Health.11,32 In the Hawaiian language ulu means to grow and it is also the name the breadfruit tree (Artocarpus altilis), which produces a popular Pacific produce. The Ulu Network is made up of 30 organizations dedicated to improving the health and well-being of NHPI communities. The Ulu Network spans nearly 70 sites across Hawai‘i and California (Figure 1) and includes all 19 federally qualified community health centers in Hawai’i and all five federally recognized Native Hawaiian Health Care Systems. Over the past decade, 11 Ulu Network organizations have served as community researchers in 15 National Institutes of Health–funded studies with the Center for Native and Pacific Health Disparities Research, including nine funded by the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities. The studies include clinical trials, translational research, and epidemiological and basic science studies. Seven of these organizations have been involved with roles ranging from community principal investigators, performance sites, and/or assisted with participant recruitment/enrollment.

Figure 1.

Map of Ulu Network Partners, 2013

To continue the progress made in community-engaged research, university researchers must increase their knowledge and skills to work ethically and meaningfully with community health organizations on research initiatives.33,34 Look and Furubayashi35 found that many community-based organizations serving NHPI would be receptive to participating in research if researchers had a better understanding of specific preferences, values, and behaviors that are congruent to these organizations and the communities they serve. The purpose of this study was to gain a better understanding of the priorities and preferences for research engagement in NHPI communities from the perspectives of community-based health leaders. To date, this is the first known study to document the research engagement needs and preferences of NHPI communities.

Methods

Participants Representing Community Organizations

Interviews with the 30 Ulu Network members were conducted as a part of a needs assessment,11 but only 24 organizations are included in this analysis regarding community-engagement in research. Two agencies declined to participate in this publication and four organizations did not respond to the specific question regarding academic research engagement because of individual preference or time constraints. Of the 50 interview participants, most were administrative leaders (47%; i.e., executive directors, CEOs) or clinical leaders (21%) such as medical directors or clinical managers (Table 1).

Table 1.

Agency and Interview Participant Information

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Agency Type (n = 24) | |

| Community health center | 10 (42) |

| Community-based civic and social organizations | 6 (25) |

| Native Hawaiian Health Care Systems | 5 (21) |

| Tertiary care institution | 2 (8) |

| Educational/government institution | 1 (4) |

| Type of Personnel Involved in Interviews (n = 50) | |

| Executive director | 22 (44) |

| Clinical leadership | 11 (22) |

| Other staff | 9 (18) |

| Administrative leadership | 8 (16) |

Procedures

The Center’s Director of Community Engagement (CE) contacted the self-identified key contact of the Ulu Network and invited the organization to participate in the needs assessment interviews including questions on research engagement. The conversation centered on the research question, “What should researchers know before engaging with communities?” and used a “talk story” style. “Talking story” is a common term in Hawai‘i, which describes a form of casual conversational interaction through co-narration of personal experiences, information, and interpretations of events by two or more storytellers that emphasizes mutual connections.36 Although the interview questions were developed by The Center staff, the talk story style was determined by the participants’ preference. The Center staff probed for additional responses by encouraging reflection about researchers who have approached their organization in the past, and the organization’s experience working on externally driven research initiatives.

The key informant interviews were with two or three staff members, which lasted 60 to 90 minutes. They were conducted by The Center staff between September 2011 and October 2012. A Center staff member arranged for date, location, and attendees for the interviews based on participant preference. Nineteen (interviews 79%) were conducted on site at the organization’s headquarters, requiring air flights to reach geographically isolated rural areas. The in-person interviews were arranged to respect the community leaders’ time, service, and responsibilities. The remaining five interviews (21%) were conducted as individual telephone conference calls because of logistical constraints or participants’ preference. The interviews were not audio taped because of the participants’ preference, and two note-takers attended all interviews. This study has been approved by the University of Hawai‘i-Mānoa Committee on Human Studies.

Data Analysis

The notes from the individual note takers were checked for completeness by The Center’s CE Director. The notes were then combined into a single document that was reviewed for clarity and accuracy by the CE Director and the research staff who were present at the interviews. Notes were imported into NVivo 10 and two university researchers individually identified emerging codes using an inductive approach for thematic analysis. The codes were assigned labels and compiled into themes. The codes and themes were compared for inter-rater agreement between the two researchers. If there was disagreement, the CE Director reviewed the themes and served as a tie breaker. This analytical process was iteratively conducted until all themes were agreed upon by the three researchers. Analysis of the number of organizations that address each theme was counted to assess the concurrence of a theme across organizations. Because of time limitations, Ulu Network partners were not involved in the data analysis. However, the findings were shared with partners for their feedback before the manuscript was submitted for publication.

Results

Generally, participants with more extensive experience in research collaborations were more specific in their preferences and more explicit in their expectations of investigators, especially in terms of resources that should be provided to their community and organization and their preferences on data ownership. Five themes were identified and are listed below, starting from the theme with the highest frequency.

Theme 1: Invest in Long-term Relationships and the Human Connection: “Relationships Are the Most Important”

Fourteen agencies (58%) spoke about the importance of dedicating the time to build relationships and trust, as well as the necessity of treating people with respect to foster those connections. According to participants, communities want to work with researchers who are interested in a long-term term relationship that extends “beyond the project timetable.” Building trust was identified as being essential to ensure true collaborative partnerships. Those interviewed believed researchers can begin developing these partnerships and building trust by “explain[ing] who you are” and “establish[ing] the human connection. Connection is critical to establish trust with collaborators AND with participants.” To nurture these connections, researchers must convey “humility,” and treat the community with “dignity,” and “respect.” Those interviewed encouraged researchers to see themselves as “guests in the community” and feel “honored to have the community participate.” The distaste for research was communicated when discussing experiences of their communities feeling like “laboratory animals,” “guinea pigs,” and being “researched to death.” One participant underscored the repercussions of cantankerous research experiences, “Don’t think the community is stupid. Don’t try to lie and/or steal by gathering data and leaving without appropriate follow-up.” Another participant emphasized the importance of relationships with the following advice: “Understand that your acceptance in the community varies on how well the community knows you or feels that they have gotten to know you.”

Theme 2: Acknowledge Individuality of Pacific Communities: “Understand How Different Each Community Is . . . You Can’t Lump All Pacific Islanders Together”

Another theme that emerged from 14 agencies (58%) was the need for researchers to have a strong understanding of each individual community and its unique cultural norms and values. Participants emphasized that researchers must recognize the uniqueness of a community that derives from its geographic location, ethnic composition, historical experiences, and present issues. They explained that the cultural diversity that exists within and among communities and investigators must avoid placing all NHPI communities into one category. In addition, researchers must know and practice the appropriate cultural protocols for the specific community and have “solid education in bedside manner.” For example, they must know the community preferences of addressing individuals. Researchers must also be aware that “every community has a gatekeeper . . . it is important to know who these gatekeepers are and to work with them or one of them.” The participants recognize that developing this understanding requires time, openness, and the ability to listen. As one participant stated about their Native Hawaiian community, “Pa‘a ka waha. Listen to the community without judgment, and listen well.”

Theme 3: Define Direct Community Benefits: “How Is This Going to Help the Community . . . More Than ‘you’ll Get a Gift Card’?”

Fourteen agencies (58%) spoke about the importance of researchers to “come in thinking about how can they give back to the community and how are they going to develop community and organizational capacity.” The research initiative must provide tangible and direct benefits to not just the individuals, but also the broader community. According to participants, identification of benefits to participation in a research effort should be at the forefront of all initial discussions. Several interviewed stated that receiving a gift card for being a research participant is clearly not sufficient. Researchers must work with the community to identify “how is this able to help me, the organization, and my patients?” This could include direct funding, capacity-building, equipment, and “giving back usable information.” The dissemination of findings should integrate ideas and solutions for how the everyday lives of the community members can be enhanced and not just be a “report back.” The findings should be used to create social action that benefits the community beyond the project.

Theme 4: Initiate Dialog Early On: “Have the Community Help Define the Research From the Start and Every Step of the Way”

Seven organizations (29%), mostly with extensive experience with academic research collaborations, discussed the importance of involving the community throughout all stages of research. They said researchers should “keep the community in mind at every stage of the process” and “learn how to co-develop hypothesis with community perspectives.” Concrete examples given included making community organizations a part of the research team and having organizational or community members involved in participant recruitment, data collection, and intervention delivery. Two organizations with considerable experience with collaborating on research studies expressed their interest in pursuing research that was “strength-based” or with a focus on “positive deviants.” Over the years of working with the community, these participants observed consistent individual or familial factors in their communities that seem to influence success in achieving wellness, which could be the basis for hypothesis development or conceptualization of a study objective. In addition, those interviewed encouraged researchers to engage communities early in the research process as one participant from a rural Native Hawaiian community stated, “our [community] people do not want to be told what to do, you must approach them early in the process and allow participation in the planning.”

Theme 5: Cultivate Organizational Knowledge: “Do Their Homework, Understand Who the Organization They Are Approaching Is About”

Seven organizations (29%) spoke about the need for the researcher to understand their specific organization, including the mission, culture, services, and structure. They expressed displeasure when investigators had unreasonable expectations of organizational resources, capacity, and interest. Participants explained research studies need to “work within the existing structure” and the limitations of the organization and “must be compatible with services” and “not be a drain” on their existing resources.

Discussion

These themes reveal that NHPI communities are interested in engaging in research if researchers are mindful of these factors that demonstrate consideration and respect. The insights shared by the community partners reinforce the idea that there are no shortcuts in community research, and researchers must be able and willing to invest their time to develop relationships with the community. Knowing the cultural protocols of the community, understanding what type of immediate and long-term outcomes would benefit the community, and having the skills to communicate the project details and findings back to the community are only possible if the researcher invests the time to develop this understanding and trust.23 Similar to the findings of other studies, communities desire for meaningful collaborations that are founded on trusting relationships, which require openness and honesty, the ability to listen well, continual communication, and the courage to directly address contentious issues as soon as possible.9,10 Over the past decade, The Center has successfully developed extensive clinical and qualitative research collaborations with a third of the Ulu Network organizations. This achievement was established over time through continuous engagement in activities that facilitated co-learning, personal relationships, and organizational capacity-building. Through constant reflection and relationship building, The Center continues to strive to enhance the collaborations and research capacity of the Ulu Network.

The importance of relationships has been recognized in the community research literature, which is reflected in the findings of this study.4 In Pacific Islander cultures, the lines between personal and professional roles are not always defined as it is the Western context. Being accepted into the Pacific communities in a professional capacity often translates into a personal connection where trusted people are welcomed into homes and family gatherings. This may be reflective of the island culture where limited resources encourage neighbors and community members to rely more heavily on one another. The history of colonization and fragmentation of the Pacific Islands also make the focus on relationship building more imperative. Researchers who are interested in engaging in research with Pacific communities must be prepared and capable to build authentic and reciprocal relationships and transform the conventional top-down approach of research where researchers are seen as the main source of expertise. If researchers expect communities to open themselves and share who they are, researchers need to reflect that same openness with themselves.

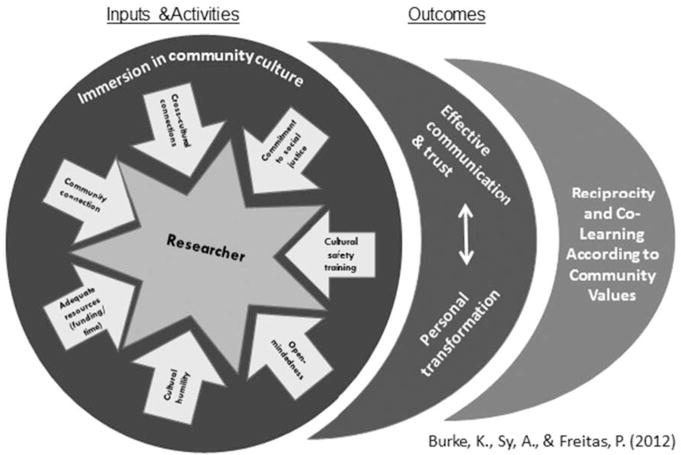

The Ripple Model (Figure 2), which was developed by one of the Ulu Network partners, provides a framework for researchers to build authentic relationship and trust in community-engaged research.37 This model shows that researchers must be willing to take the time to personally invest in developing these areas, which may be called “inputs” or “activities” in academia, and are conceptualized as “gifts” or “gift cultivation” in the community. By being willing and open to immersing ourselves in the culture of the community as well as our own, researchers can began building the “human connection” that is desired by the community. Having adequate resources, such as funding and time, also drives the possibility to take the time for this immersion and engagement to take place. Possessing cultural humility also impacts the level of growth and transformation of researchers to be able to “listen to the community without judgment and listen well.” Engaging in cultural safety training by becoming grounded in our own culture and ancestry to learn about the community’s cultural protocols can help researchers stay mindful of the ethical concerns, which drives the commitment to social justice.38

Figure 2.

Ripple Model for Community-Engaged Researchers

This immersion into a community’s “culture” can have a rippling effect by enhancing effective communication and building trust between the researcher and the community. Researchers learn that the creation of a relationship is the valued outcome and not just the process of community-engaged research.38 This relational outcome can remind researchers to come into the community with humility and have compassion for the qualities identified by the community participants in this study. This iterative process invests in relationship building and explicitly places value on reciprocity and co-learning for all partners to work collectively on community-driven research agendas. One potentially adverse effect of researchers becoming more “in tune” with their communities is that their relationship may introduce bias into a study. We propose that developing a more meaningful relationship with communities for which we profess to design research to improve their lives would allow us to ensure stronger external validity (i.e., that it will work in the real world). This requires a “paradigm shift” of our role as researchers in understanding health disparities as a social justice issue that prioritizes community engagement.1

The findings of this study are limited to the perspectives of the organizations who work with Pacific communities in Hawai‘i and California. They do not include organizations from other Pacific communities in the United States or Pacific Island countries. In addition, the interviews were conducted with leadership from organizations and may not represent the perspectives of the organizational participants, staff members who work directly with the community, or other community members. However, organizational leaders are essential gatekeepers to research initiatives and understanding their perspectives can help to strengthen community–university collaborations.

For community-placed research to advance into community-engaged and community-driven research, individual and institutional capacities need to be fostered to better understand the complex relationships that they are pursuing in conducting research studies. This study provided a basis for training emerging researchers preparing for work with NHPI communities. One training tool has been a “Community 101 for Researchers” online self-directed seminar (available from: http://rmatrix2.jabsom.hawaii.edu/community-101/) that was specifically created for health disparities investigators working with Pacific populations.39 Providing various training and mentoring opportunities related to community-based research for graduate students and faculty can help build workforce and instructional capacity, along with modifying tenure and promotion guidelines that prioritize and reward research initiatives based on community impact.34,40 This would provide researchers the intentional space to “generate trust [in the community] through our actions”41(p9) and engage in the transformative process illustrated in the Ripple Model.

At the same time, building the research capacity of community organizations is also integral to the progress of community-engaged research.41 Both community and researcher partners need to be aware of the challenges and limitations of the organization and possess the flexibility and responsiveness to adapt to changing needs and resources as they emerge, which requires a strong foundation of trusting relationships. Researchers must offer continuous efforts directed at building community-based capacity as equal research partners and investigators. This should not be limited to scientific process skills, but include infrastructure capacity in handling awards and receiving indirect administrative costs.40 Working with organizations to build their capacity so that they can become their own fiscal agents on future community research grants can also help address historical power differentials among researchers and communities.2,42 Community-based research institutes would foster the community’s capacity to set their own research agenda, leading to equitable and authentic partnerships that truly benefit community wellness.

Acknowledgments

Mahalo piha is extended to the Ulu Network organizations and their commitment to Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Peoples. The project was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (U54MD007584 and P20MD00173), National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the Queen’s Health System. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities or NIH.

References

- 1.Danka-Mullan I, Rhee KB, Stoff DM, Pohlaus JR, Sy FS, Stinson N, et al. Moving toward paradigm-shifting research in health disparities through translation, transformational, and transdisciplinary approaches. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:S19–S24. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.189167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minkler M, Blackwell AG, Thompson M, Tamir H. Community-based participatory research: implications for public health funding. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(8):1210–3. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.8.1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wallerstein NB, Duran B. Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promot Prac. 2006;7:312–23. doi: 10.1177/1524839906289376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: From Process to Outcomes. San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ammerman A, Corbie-Smith G, St George DM, Washington C, Weathers B, Jackson-Christian B. Research expectations among African American church leaders in the PRAISE! project: A randomized trial guided by community-based participatory research. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(10):1720–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.10.1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coutin-Foster C, Phillips E, Palermo AG, Boyer A, Fortin P, Rashid T, et al. The role of community-academic partnerships: Implications for medical education, research, and patient care. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2008;2(1):55–60. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2008.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cook WK. Integrating research and action: a systematic review of community-based participatory research to address health disparities in environmental and occupational health in the USA. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62(8):668–76. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.067645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fong M, Braun KL, Tsark J. Improving Native Hawaiian health through community-based participatory research. Calif J Health Promot. 2003;1(Special issue):136–48. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sullivan M, Kone A, Senturia KD, Chrisman NJ, Ciske SJ, Krieger JW. Researcher and researched—community perspectives: toward bridging the gap. Health Educ Behav. 2001;28:130–49. doi: 10.1177/109019810102800202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vawer M, Kaina P, Leonard A, Ogata M, Blackburn B, Young M, et al. Navigating the cultural geography of indigenous peoples’ attitude toward genetic research: The Ohana (family) Heart Project. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2013:72. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v72i0.21346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Look MA, Trask-Batti MK, Agres R, Mau ML, Kaholokula JK. Assessment and priorities for health & wellness in Native Hawaiians & Other Pacific Peoples. Honolulu: Center for Native and Pacific Health Disparities Research, University of Hawai‘i; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beaglehole JC. The Journals of Captain James Cook—The Voyage of the Resolution & Discovery 1776–1780, Part 1 & 2. London: Cambridge University Press; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaholokula JK, Nacapoy AAH, Dang K. Social justice as a public health imperative for Kānaka Maoli. AlterNative. 2009;5(2):117–37. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marshall WE. Remembering Hawaiian, transforming shame. Anthropology and Humanism. 2006;31:185–200. [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCubbin LD, Marsella A. Native Hawaiians and psychology: The cultural and historical context of indigenous ways of knowing. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2009;15(4):374–87. doi: 10.1037/a0016774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meyer MA. Our own liberation: Reflections on Hawaiian epistemology. Contemp Pac. 2001;13(1):124–48. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mau MK, Sinclair K, Saito EP, Baumhofer KN, Kaholokula JK. Cardiometabolic Health Disparities in Native Hawaiians and Other Pacific Islanders. Epidemiol Rev. 2009;31(1):113–29. doi: 10.1093/ajerev/mxp004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bushnell OA. Gifts of Civilization: Germs and Genocide in Hawai‘i. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson DB, Oyama N, LeMarchand L, Wilkens L. Native Hawaiians mortality, morbidity, and lifestyle: Comparing data from 1983, 1990, and 2000. Pac Health Dialog. 2004;11(2):120–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moy KL, Sallis JF, David KJ. Health indicators of Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders in the United States. J Comm Health. 2010;35:81–92. doi: 10.1007/s10900-009-9194-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Santos L. Genetic research in native communities. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2008;2(4):321–7. doi: 10.1353/cpr.0.0046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pobutsky AM, Buenconsejo-Lum L, Chow C, Palafox N, Maskarinec GG. Micronesian Migrants in Hawaii: Health issues and culturally appropriate, community-based solutions. Calif J Health Promot. 2005;3(4):59–72. [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Cambra H, Enos R, Matsunaga DS, Hammond OW. Community involvement in minority health research: Participatory research in a Native Hawaiian community. Cancer Control for Public Health: Research Reports. [updated 1992]. Available from: http://www.wili.org/docs/CommunityInvolvement.pdf.

- 24.Chang RM, Lowenthal PH. Genetic research and the vulnerability of Native Hawaiians. Pacific Health Dialog. 2001;8(2):364–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Christopher S, Watts V, McCormick AK, Young S. Building and maintaining trust in a community-based participatory research partnership. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(8):1398–406. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.125757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boyd JK, Kamaka SAK, Braun K. A values-based college-community partnership to improve long-term outcomes of under-represented students. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2012;6(10):25–31. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2012.0006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chung-Do J, Helm S, Fukuda M, Nishimura S, Else I. Rural mental health: Implications for telepsychiatry in clinical service, workforce development, and organizational capacity. Telemed J E Health. 2012;18(3):244–6. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2011.0107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jarmon J. Neighborhood—The small unit of health: A health center model for Pacific Islander and Asian Health. Poverty & Race. 2011;20(4):13–6. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Health Research Council of New Zealand. Guidelines on Pacific Health Research. Auckland: Health Research Council of New Zealand; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Look MA, Kaholokula JK, Carvahlo A, Seto TB, de Silva M. Developing a culturally based cardiac rehabilitation program: The HELA Study. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2012;6(10):103–10. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2012.0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mau MK, Kaholokula JK, West MR, Leake A, Efrid JT, Rose C, et al. Translating diabetes prevention into Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander communities: The PILI ‘Ohana Pilot Project. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2010;4(1):7–16. doi: 10.1353/cpr.0.0111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaholokula JK, Saito E, Shikuma C, Look M, Spencer-Tolentino K, Mau MK. Native and Pacific health disparities research. Hawaii Med J. 2008;67(8):218–9. 222. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gebbie KM, Rosenstock L, Hernandez LM. Who will keep the public healthy? Educating public health professionals for the 21st century. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nyden P. Academic incentives for faculty participation in community-based participatory research. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(7):576–85. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20350.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Look MA, Furubayashi JK. Ulu network strategic directions: 2004–2007 [Internet] Honolulu: Center for Native and Pacific Health Disparities Research; 2004. Available from: http://www2.jabsom.hawaii.edu/native/comm_ulu-reports.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watson-Gegeo KA. Ethnography in ESL: Defining the essentials. TESOL Quarterly. 1988;22(4):575–92. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burke KY, Freitas P, Sy A. ‘Āina-based Health Programs: A Place to Grow Community-Engaged Performative Researchers. Presentation at the Pacific Global Health Conference; October 8–10 2012; Honolulu, Hawai‘i. [cited 2014 Dec]. Available from: http://www.hawaiipublichealth.org/resources/PGHC2012/PGHC_AbstractBooklet2012.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tolich M. Pākehā “paralysis”: Cultural safety for those researching the general population of Aotearoa. Social Policy J New Zealand. 2002;19:164–78. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Community 101 for researchers: An educational program for researchers working in grassroots communities. [updated 2013; cited 2014 Dec]. Available from: http://rmatrix2.jabsom.hawaii.edu/community-101/

- 40.Hicks S, Curan B, Wallerstein N, Avila M, Belone L, Magarati M, et al. Evaluating community-based participatory research to improve community-partnered science and community health. Prog Community Health Partners. 2012;6(3):289–99. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2012.0049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oneha MF, Dodgson JE. Lessons learned: Refining the research infrastructure at community health centers. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2014;8(1):61–5. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2014.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Israel BA, Schultz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]