Abstract

A responsive magnetic resonance (MRI) contrast agent has been developed that can detect the enzyme activity of DT-diaphorase. The agent produced different chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) MRI signals before and after incubation with the enzyme, NADH, and GSH at different pH values whereas it showed good stability in a reducing environment without enzyme.

Keywords: CEST MRI, dt-diaphorase, molecular imaging, NQO1, trimethyl lock

DT-diaphorase (DTD), also known as NAD(P)H-Quinone Oxyreductase 1 (NQO1), is a flavoenzyme that catalyzes the two-electron reduction of quinone, quinone imines, and azo dyes in the presence of NAD(P)H,[1] which results in detoxification of cells from xenobiotics.[2] The enzyme is upregulated in non-small cell lung carcinoma, colorectal carcinoma, liver cancers, as well as in breast carcinomas in various cell organelles, cytosol, and extracellular regions. High expression of DTD is correlated with a lower disease free survival and overall survival.[3] For comparison, normal tissues have low expression levels of the enzyme.[4]

DTD can bioreductively activate quinone-based prodrugs to facilitate selective chemotherapy.[5] Resistance to chemotherapy with quinone-bearing drugs has been associated with downregulation of DTD,[6] and the determination of DTD activity has been suggested as a measure of quinone-bearing anti-tumor-drug resistance.[7] Mitomycin C and its derivatives such as EO9 (apaziquone) have been extensively investigated as prodrugs activated by DTD in various types of cancers[8] and several ongoing clinical trials (such as NCT02563561) are based on the therapeutic effect of these compounds.[5a,9] However, stratifying patients for chemotherapy with quinone-based drugs is a notable challenge.

The reductive lactonization of quinone propionic amide was first introduced as a novel strategy for controlled drug release.[10] This class of organic molecules uses a trimethyl lock (TML), which benefits from a steric effect between a methyl group on the quinone ring and two methyl groups on the propionic acid side chain that accelerates the rate of lactonization by a factor of ≈1016 M.[11] This feature made TML an ideal tool for developing a trigger for molecular release with applications in chemistry, biology, and pharmacology.[12] The introduction of latent fluorescent agents based on TML provided new applications of this compound for imaging studies.[13] More recently, several fluorescence TML-based quinone agents were introduced for detecting DTD in cancer[14] and as theranostics for imaging as well as therapeutic applications.[15] Although these agents provide novel tools for detecting enzyme activity, the limited depth of view of fluorescence imaging within in vivo tissues demands another class of agents that detect enzyme activity in deep tissues.

Chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) is a relatively new magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technique with promising applications that detect enzymes, redox state, metabolites, and measurement of pH and temperature, with some of these applications advancing to preclinical and clinical studies.[16] The CEST technique offers several advantages relative to conventional MRI techniques including selectively turning the signal on and off, the capability to detect multiple CEST signals from various labile protons on the same agent or from different agents, and more flexibility in designing responsive MRI agents for a particular target by simply changing functional groups. To generate CEST, selective saturation occurs by using a radiofrequency pulse that matches the resonance frequency of exchangeable protons on a contrast agent, which suppresses the MR signal from that proton. The exchange of the saturated proton between the contrast agent and surrounding water molecules can transfer saturation from the contrast agent to the water and consequently some water molecules lose MR signal. The measurement of water signals while saturating pulses are iteratively applied over a range of MR frequencies provides a CEST spectrum, in which exchangeable protons produce signals with unique chemical shifts.[17]

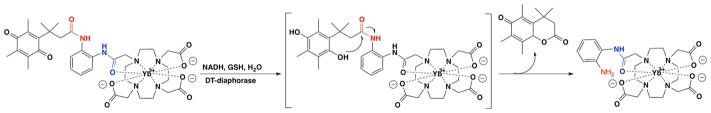

We previously reported Yb-DO3A-oAA as a CEST MRI agent that produces a CEST signal from a proton of the amide functional group connecting the aniline ring to the DO3A chelate and another CEST signal from the protons of the amine group on the aniline ring.[18] We have shown that adding a relatively large ligand to the aniline group causes a loss of one or both CEST signals.[19] Therefore we decided to attach a quinone moiety to the aniline ring of the molecule to eliminate the CEST signal from the protons of the amine group of the aniline ring to develop a responsive agent that detects DTD. We hypothesized that reduction of the quinone functional group to a hydroquinone group followed by intramolecular reaction of the newly formed hydroxyl functional group and the amide bond would release the CEST agent, which consequently would produce two CEST signals (Scheme 1).[10a]

Scheme 1.

The quinone functional group in Yb-DO3A-oAA-TML-Q was reduced to hydroquinone in the presence of DT-diaphorase enzyme, NADH, and GSH. The newly formed hydroxy group attacked and dissociated the amide bond as a result of the steric effect between the methyl group on the benzene ring and the two adjacent methyl groups, consequently resulting in the release of the CEST agent.

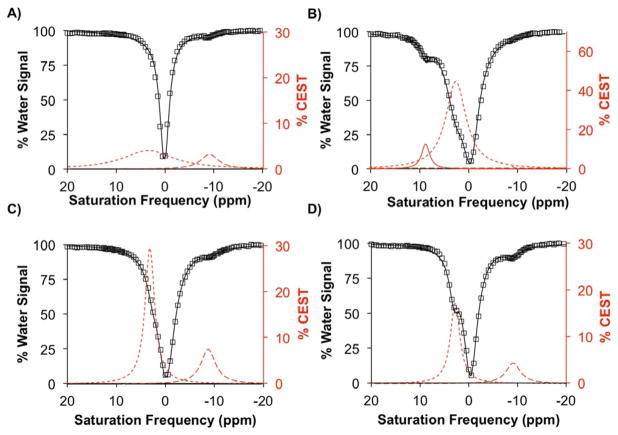

The agent was tested in several buffer systems, and PBS offered the best activation of the cloaked CEST agent in the presence of DTD enzyme, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH), and glutathione (GSH). The cloaked CEST agent at a concentration of 12 mM in PBS showed 3.2 % CEST signal at −9 ppm (dashed red line in Figure 1A) arising from the proton of the amide functional group connecting the aromatic ring to the Yb-DO3A chelate (blue amide in Scheme 1). No signal at 9 ppm was observed, at which the free amine would show a CEST signal. However, the presence of a broad peak with 4.1 % CEST signal at 3.5 ppm (dotted red line in Figure 1A) validated that the second amide group was present in the agent.

Figure 1.

Yb-DO3A-oAA-TML-Q was reacted with DT-diaphorase enzyme at pH 8.1 ± 0.1 and 37 °C for 15 h. CEST spectra were acquired with 6 μT, saturation power applied for 4 sec. (A) No reaction was detected when no enzyme, GSH, and NADH were added to the solution. (B) A new CEST signal at 9 ppm (solid red line) was detected when the CEST MRI agent was reacted with the enzyme, GSH, and NADH. The absence of NADH (C) or GSH (D) did not allow formation of the desired product whereas the CEST signal of unactivated CEST MRI agent (dashed lines in C and D) was clearly detected.

After incubation of the cloaked CEST agent (12 mM) with 10 units (100 μg) of DTD enzyme, NADH (71 mM), and GSH (47 mM), the solution generated 12.5 % CEST signal at 9 ppm (red line in Figure 1B). The solution also showed 0.9 % CEST signal at −9 ppm (dashed red line in Figure 1B) indicating that some unreacted agent remained in the sample. In addition, a 44 % CEST signal at 2.5 ppm was observed (dotted red line in Figure 1B), which was attributed to the amide protons of NADH and GSH as shown experimentally (Figure S1 in the Supporting Information). Formation of the product was also validated with mass spectroscopy which confirmed that Yb-DO3A-oAA was released from the cloaked CEST agent (Figure S2) only with DTD, NADH, and GSH.

We evaluated the stability of the CEST MRI contrast agent to confirm the specificity toward the reductase enzyme, NADH, and GSH for activation. The cloaked CEST agent was incubated with DTD and NADH without GSH, and with DTD and GSH without NADH. Analysis of the solution with MRI showed 7.2 % CEST at −9 ppm for the solution with NADH and the enzyme (Figure 1C), and 4.6 % CEST at −9 ppm for the solution with GSH and the enzyme (Figure 1D) with no CEST signal at 9 ppm, indicating that all reaction components were needed for the activation of the agent.

Similar optical agents can be activated with the enzyme and NADH without requiring GSH, because the optical agents can be detected at nM-to-μM concentrations and thus a high ratio of NADH relative to the optical agents can be used to complete the reaction in a short time. Using a higher ratio of NADH relative to our CEST agent was impractical because a large concentration of NADH causes a line-broadening effect that overlaps with the signal from the activated CEST agent. However, this would not create a limitation in vivo considering that NADH is in a relatively low concentration and is produced through cyclic reduction of NAD+. Therefore continuous production of NADH would provide enough concentration of the co-enzyme for the enzymatic reaction. A smaller ratio of NADH relative to the CEST agent in combination with instability of the reduced form of NADH in solutions under oxidative conditions will result in a reaction with low yield or longer experiment time. A solution to this problem is addition of GSH to prevent oxidation of NADH.

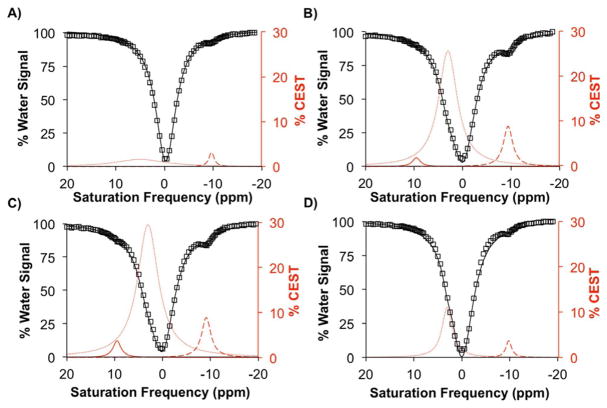

The same reactions were performed in an anaerobic chamber to investigate the effect of a reducing environment on the activation of the agent. No signal indicating activation of the agent was detected in the solution of the cloaked CEST agent without NADH or DTD enzyme, and the 2.8 % CEST signal at −9.75 ppm indicated that the cloaked CEST agent was completely stable in anaerobic conditions (Figure 2A). The cloaked CEST agent incubated with the enzyme and NADH with GSH under anaerobic conditions produced 2.0 % and 8.9 % CEST signals at 9 ppm and −9.5 ppm, respectively, indicating that some of the cloaked CEST agent was activated (Figure 2B). Interestingly, the solution of the cloaked CEST agent with the enzyme and NADH without GSH produced 3.5 % CEST at 9 ppm and 8.5 % CEST at −9.25 ppm (Figure 2B) indicating that anaerobic conditions could substitute for GSH in activating the cloaked agent. Therefore the reducing environment of tumors could potentially be sufficient for activation of the cloaked agent. However, the activation of the agent did not occur without NADH (Figure 2D) showing that NADH was still required. Furthermore, in reducing environments, NADH remains in its active (reduced) form for a longer time that accelerates activation of the cloaked CEST agent. Interestingly, the agent is sufficiently stable to tolerate such a reducing environment even in the presence of GSH. Such stability makes the CEST agent specific for the detection of the enzyme.

Figure 2.

Yb-DO3A-oAA-TML-Q showed stability under anaerobic conditions (A) whereas the presence of DT-diaphorase enzyme and NADH in presence (B) or absence (C) of GSH activated the agent and produced a CEST signal at 9 ppm at pH 7.0 ± 0.25, 37 °C for 15 h, power level of 6 μT, and saturation time of 4 sec. The agent showed good stability in a reducing environment even in the presence of the enzyme and GSH in an anaerobic chamber (D).

We adjusted the pH of the solutions to 8.0 because previous reports showed that this pH was suitable for increasing the stability of NADH.[20] However, the basic pH caused a decrease in the CEST signal of the amide group in the activated form of the agent. A neutral pH (7.0 ± 0.25) was suitable to observe both CEST signals of the activated agent. Small 0.75 ppm shifts in saturation frequencies of CEST signals were observed that were due to differences in pH 8.1 and 7.2 between the samples. The pH-dependent changes in protonation of functional groups can alter resonance frequencies of labile protons.[21] In addition, changes in the exchange rates of labile protons affect their resonance frequencies.

Further evidence of activation of the cloaked CEST agent was obtained by measuring UV/Vis absorbance of solutions before and after reaction. A solution of NADH showed two major absorbance peaks at 260 and 339 nm (teal line in Figure S3 in the Supporting Information). The pure solution of the cloaked agent with or without GSH showed only one peak at 260 nm (purple line and green line in Figure S3). The solutions containing the cloaked CEST agent incubated with the enzyme and NADH, with or without GSH under anaerobic conditions, showed an appearance of a shoulder at 292 nm (blue and red lines in Figure S3).

The magnitude of the CEST signal is directly correlated with the saturation power level applied during a CEST MRI experiment.[19b] In our studies, increasing the power level is favorable for producing a larger CEST signal, which facilitates signal detection. However, a relatively low power level is preferred in a clinical setting due to concerns for patient safety. Our results suggested that a power level as low as 3.5 μT was sufficient to produce detectable signals, which is a safe level for future in vivo studies.

In conclusion, we have introduced a new responsive CEST MRI agent for the detection of DT-diaphorase enzyme. The cloaked CEST agent showed only one signal at −9 ppm before activation. In the presence of the enzyme, NADH, and GSH, the agent showed a different signal at 9 ppm after activation. The agent exhibited good stability in a reducing environment where no activation was observed. This cloaked agent is a promising template for the design of molecules for in vivo studies that investigate reductase activity within tissues.

Experimental Section

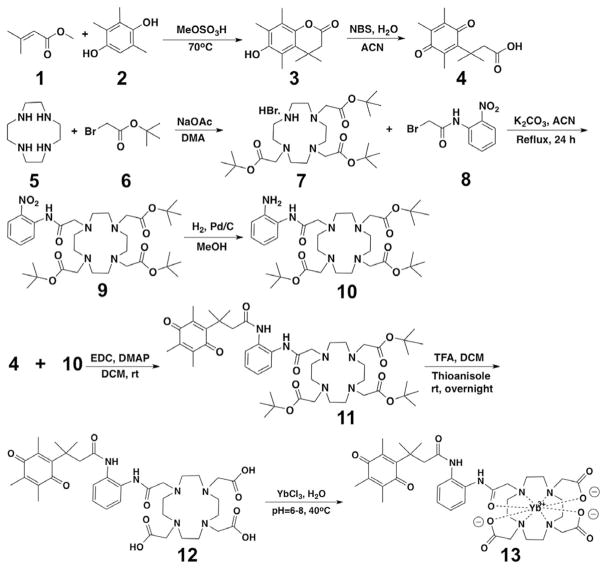

The cloaked CEST agent was synthesized in 8 steps (Scheme 2) according to previously reported methodologies with some modifications.[10a,19a] We conjugated the carboxylic acid form of the quinone 4 to tBu protected DO3A-oAA compound (10) taking advantage of the moderate reaction and flexibility of the reaction with low boiling point solvents such as dichloromethane. In addition, the product of this step was easily purified with gravity column chromatography. The tBu groups were removed upon purification. The qui-none moiety was sufficiently stable and tolerated harsh acidic conditions during deprotection of the DO3A-oAA macrocycle. Finally, YbIII was chelated with DO3A-oAA in water at 40°C. The final product was synthesized with an overall isolated yield of 6 % and was purified using HPLC. Different combinations of the cloaked agent, DT-diaphorase enzyme, β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, and glutathione were incubated at 37°C and their CEST signals were measured using a 7 T Bruker Biospec MRI scanner.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of Yb-DO3A-oAA-TML-Q. The caboxylic acid form of quinone was prepared in 2 steps. Then it was reacted with tert-butyl protected DO3A-oAA that was prepared in 3 steps. The resulting product was de-protected and then used to chelate YbIII.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Vahe Bandarian and Micah T. Nelp for access to their laboratory instruments and active involvement in setting up enzyme reactions. The authors also thank Dr. Indraneel Ghosh, Dr. Karla Camacho-Soto, and Dr. Luca Ogunleye for access to their laboratory instruments and assistance with HPLC analysis and purifications. This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) through grants R01 CA169774 and P01 CA95060. K.M.J. was supported through NIH training grants T32HL007955 and T32HL066988.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information and the ORCID identification number(s) for the author(s) of this article can be found under https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.201700721.

References

- 1.Belinsky M, Jaiswal AK. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1993;12:103–117. doi: 10.1007/BF00689804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Chen S, Wu K, Knox R. Free Radical Biol Med. 2000;29:276–284. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00308-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Tedeschi G, Chen S, Massey V. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:1198–1204. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.3.1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ma Y, Kong J, Yan G, Ren X, Jin D, Jin T, Lin L, Lin Z. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:414–423. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Dansona S, Ward TH, Butler J, Ranson M. Cancer Treat Rev. 2004;30:437–449. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Winski SL, Koutalos Y, Bentley DL, Ross D. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1420–1424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Gutierrez PL. Free Radical Biol Med. 2000;29:263–275. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00314-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Gharat L, Taneja R, Weerapreeyakul N, Rege B, Polli J, Chikhale PJ. Int J Pharm. 2001;219:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(01)00599-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Sagara N, Katoh M. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5959–5962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Riley RJ, Workman P. Biochem Pharmacol. 1992;43:1657–1669. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(92)90694-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.a) Glorieux C, Sandoval JM, Dejeans N, Ameye G, Poirel HA, Verrax J, Calderon PB. Life Sci. 2016;145:57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2015.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Siegel D, Yan C, Ross D. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;83:1033–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.a) Phillips RM. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2016;77:441–457. doi: 10.1007/s00280-015-2920-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Phillips RM, Hendriks HR, Peters GJ. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;168:11–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.01996.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Noura S, Ohue M, Shingai T, Kano S, Ohigashi H, Yano M, Ishikawa O, Takenaka A, Murata K, Kameyama M. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:396–404. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1319-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Phillips RM, Naylor MA, Jaffar M, Doughty SW, Everett SA, Breen AG, Choudry GA, Stratford IJ. J Med Chem. 1999;42:4071–4080. doi: 10.1021/jm991063z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Siegel D, Beall H, Senekwitsch C, Kasai M, Arai H, Gibson NW, Ross D. Biochemistry. 1992;31:7879–7885. doi: 10.1021/bi00149a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Siegel D, Gibson NW, Preusch PC, Ross D. Cancer Res. 1990;50:7483–7489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a) Shimizu T, Murata S, Sonoda H, Mekata E, Ohta H, Takebayashi K, Miyake T, Tani T. Mol Clin Oncol. 2014;2:399–404. doi: 10.3892/mco.2014.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Glynne-Jones R, Kadalayil L, Meadows HM, Cunningham D, Samuel L, Geh JI, Lowdell C, Beare RJ, Begum R, Ledermann JA, Sebag-Montefiore D. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:1616–1622. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Giang I, Erin EL, Boland L, Poon GMK. AAPS J. 2014;16:899–916. doi: 10.1208/s12248-014-9638-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Guise CP, Mowday AM, Ashoorzadeh A, Yuan R, Lin W-H, Wu d-H, Smaill JB, Patterson AV, Ding K. Chin J Cancer Res. 2014;33:80–86. doi: 10.5732/cjc.012.10285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.a) Carpino LA, Triolo SA, Berglund RA. J Org Chem. 1989;54:3303–3310. [Google Scholar]; b) Amsberry KL, Borchardt RT. Pharm Res. 1991;8:323–330. doi: 10.1023/a:1015885213625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Wang B, Liu S, Borchardt RT. J Org Chem. 1995;60:539–543. [Google Scholar]

- 11.a) Danforth C, Nicholson AW, James JC, Loundon GM. J Am Chem Soc. 1976;98:4275–4281. [Google Scholar]; b) Amsberry KL, Borchardt RT. J Org Chem. 1990;55:5867–5877. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levine MN, Raines RT. Chem Sci. 2012;3:2412–2420. doi: 10.1039/C2SC20536J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chandran SS, Raines KA, Dickson RT. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:1652–1653. doi: 10.1021/ja043736v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.a) Hettiarachchi SU, Prasai B, McCarley RL. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:7575–7578. doi: 10.1021/ja5030707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Silvers WC, Payne AS, McCarley RL. Chem Commun. 2011;47:11264–11266. doi: 10.1039/c1cc14578a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Silvers WC, Prasai B, Burk DH, Brown ML, McCarley RL. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:309–314. doi: 10.1021/ja309346f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu P, Xu J, Yan D, Zhang P, Zeng F, Li B, Wu S. Chem Commun. 2015;51:9567–9570. doi: 10.1039/c5cc02149a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daryaei I, Pagel MD. Res Rep Nucl Med. 2015;5:19–32. doi: 10.2147/RRNM.S81742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woods M, Woessner DE, Sherry AD. Chem Soc Rev. 2006;35:500–511. doi: 10.1039/b509907m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.a) Sheth VR, Li Y, Chen LQ, Howison CM, Flask CA, Pagel MD. Magn Reson Med. 2012;67:760–768. doi: 10.1002/mrm.23038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Sheth VR, Liu G, Li Y, Pagel MD. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2012;7:26–34. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Liu G, Li Y, Sheth VR, Pagel MD. Mol Imaging. 2012;11:47–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.a) Li Y, Sheth VR, Liu G, Pagel MD. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2011;6:219–228. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Liu G, Li Y, Pagel MD. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58:1249–1256. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rover L, Jr, Fernandes JCB, de Oliveira Neto G, Kubota LT, Katekawa E, Serrano SHP. Anal Biochem. 1998;260:50–55. doi: 10.1006/abio.1998.2656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu Y, Soesbe TC, Kiefer GE, Zhao P, Sherry AD. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:14002–14003. doi: 10.1021/ja106018n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.