Abstract

Background

Docetaxel (D) at the time of starting androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) for metastatic castrate naive prostate cancer shows a clear survival benefit for patients with high-volume (HV) disease. It is unclear whether patients with low-volume (LV) disease benefit from early D.

Objective

To define the overall survival (OS) of aggregate data of patient subgroups from the CHAARTED and GETUG-AFU15 studies, defined by metastatic burden (HV and LV) and time of metastasis occurrence (at diagnosis or after prior local treatment [PRLT]).

Design, setting, and participants

Data were accessed from two independent phase III trials of ADT alone or ADT + D—GETUG-AFU15 (N = 385) and CHAARTED (N = 790), with median follow-ups for survivors of 83.2 and 48.2 mo, respectively. The definition of HV and LV disease was harmonized.

Outcome measurements and statistical analysis

The primary end point was OS.

Results and limitations

Meta-analysis results of the aggregate data showed significant heterogeneity in ADT + D versus ADT effect sizes between HV and LV subgroups (p = 0.017), and failed to detect heterogeneity in ADT + D versus ADT effect sizes between upfront and PRLT subgroups (p = 0.4). Adding D in patients with HV disease has a consistent effect in improving median OS (HV-ADT: 34.4 and 35.1 mo, HV-ADT + D: 51.2 and 39.8 mo in CHAARTED and GETUG-AFU15, respectively; pooled average hazard ratio or HR (95% confidence interval [CI]) 0.68 ([95% CI 0.56; 0.82], p < 0.001). Patients with LV disease showed much longer OS, without evidence that D improved OS (LV-ADT: not reached [NR] and 83.4; LV-ADT + D: 63.5 and NR in CHAARTED and GETUG-AFU15, respectively; pooled HR (95% CI) 1.03 (95% CI 0.77; 1.38). Aggregate data showed no evidence of heterogeneity of early D in LV and HV subgroups irrespective of whether patients had PRLT or not. Post hoc subgroup analysis was based on aggregated data from two independent phase III randomized trials.

Conclusions

There was no apparent survival benefit in the CHAARTED and GETUG-AFU15 studies with D for LV. Across both studies, early D showed consistent effect and improved OS in HV patients.

Patient summary

Patients with a higher burden of metastatic prostate cancer starting androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) have a poorer prognosis and are more likely to benefit from early docetaxel. Low-volume patients have longer overall survival with ADT alone, and the toxicity of docetaxel may outweigh its benefits.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, Metastatic castrate naive prostate cancer, Metastatic prostate cancer, High volume, Low volume, Volume disease, Androgen deprivation therapy, Docetaxel, Chemotherapy

1. Introduction

Despite an important increase in the number of therapeutic options, prostate cancer remains the fifth leading cause of cancer death in males worldwide [1] and the third cause in Western countries [2]. The management of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer is based on chemotherapy [3–5] and new hormone therapies [6–9]. In the metastatic castrate naive prostate cancer (mCNPC) setting, androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) has been the standard of care for decades, until clinical studies established the benefits of adding docetaxel (D) to ADT. Three clinical trials evaluated this strategy—two phase III randomized trials that compared D + ADT versus ADT alone (CHAARTED [10] and GETUG-AFU15 [11]) and the multiarm, multistage STAMPEDE trial [12]. The CHAARTED study demonstrated a significant improvement in overall survival (OS) in the ADT + D arm (57.6 vs 44 mo), which was more pronounced in patients with high-volume (HV) disease (49.2 vs 32.2 mo) [10]. The updated results, presented at the European Society for Medical Oncology congress in 2016, after a median follow-up of 54 mo confirmed significantly longer OS in the overall population. A post hoc subset analysis according to the extent of disease suggests that the survival benefit could primarily be limited to patients classified as having HV disease but not in those with low-volume (LV) disease [13]. The STAMPEDE study also demonstrated longer OS when D was added to standard of care in metastatic patients (hazard ratio [HR] 0.80, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.65; 0.99, p = 0.033) but did not classify patients by volume of metastases. In contrast, the French GETUG-AFU15 study showed no significant difference in OS between ADT + D and ADT-alone arms (58.9 vs 54.2 mo, HR 1.01 [95% CI: 0.75; 1.36], p > 0.9) [11]. A further analysis, published in 2016 after a median follow-up of 84 mo, confirmed a non–statistically significant improvement in median OS for ADT + D (62.1 vs 48.6 mo, HR 0.88 [95% CI 0.68; 1.14], p = 0.3) [14].

A meta-analysis of these three trials (2992 patients) demonstrated an absolute improvement of 9% in 4-yr OS when D was added to ADT, corresponding to a 23% reduction in the risk of death (HR 0.77 [95% CI 0.68; 0.87], p < 0.001), along with a 16% absolute improvement in failure-free survival [15]. The authors concluded that the addition of D should be considered as the new standard of care for patients with mCNPC who are starting first-line therapy. However, they observed that the majority of patients included were newly diagnosed with metastatic disease, which is not the most frequent situation in clinical practice due to the development of screening programs [16,17]. In the GETUG-AFU15 study, it had been suggested that patients who developed metastases after failure of local treatment had significantly longer median OS than those with metastases at diagnosis (83.1 vs 46.5 mo, p = 0.015) [14]. In the present study, we analyzed OS in specific subgroups of patients from the CHAARTED and GETUG-AFU15 studies, defined by same definitions of metastatic burden (HV or LV) and time of metastasis occurrence (at diagnosis or after failure of local therapy), to see if the outcomes of the different subgroups are reproducible across the two studies.

2. Patients and methods

The CHAARTED and GETUG-AFU15 studies are phase III, open-label, randomized trials. Eligible patients were aged at least 18 yr and had histologically confirmed prostate cancer with radiological evidence of metastases, an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0–2, and adequate organ function, allowing the administration of D. ADT for metastatic disease was allowed if it had been initiated no more than 2 mo (GETUG-AFU15) or no more than 4 mo (CHAARTED) before randomization. Patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to ADT (orchiectomy or luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone agonists) or ADT + D (75 mg/m2 every 21 d). Patients received premedication with a corticosteroid without subsequent administration of daily prednisone. The planned duration of chemotherapy was six cycles in CHAARTED and nine cycles in GETUG-AFU15. Patients randomized in the ADT + D arm underwent physical examination and blood tests every 3 wk during chemotherapy and every 3 mo thereafter, while these parameters were recorded every 3 mo from the onset of studies for patients in both ADT arms. Imaging (computed tomography [CT] scan and bone scintigraphy) was performed every 3 mo in the GETUG-AFU15 study, at baseline, at the time of documented castration resistance, or as clinically indicated in the CHAARTED study. Time to castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) was defined as the time from randomization to prostate-specific antigen (PSA) progression, or radiological or clinical progression, whatever occurred first. Clinical progression was determined using RECIST criteria, version 1.0, for measurable lesions or the occurrence of (new) bone lesions. In the CHAARTED study, patients were stratified at randomization according to age (<70 vs ≥70 yr), ECOG performance-status score (0 or 1 vs 2), planned use of combined androgen blockade for more than 30 d (yes vs no), and agents approved for prevention of skeletal-related events (yes vs no) [10]. Patients were also stratified according to the duration of prior adjuvant ADT (<12 vs ≥12 mo) and the extent of metastatic disease group as HV disease, defined as the presence of visceral metastases and/or at least four bone metastases with at least one outside the vertebral bodies and pelvis, and LV disease for other patients. Of note, at study inception, only patients with HV disease were eligible; then an amendment allowed inclusion of patients with LV disease. In the GETUG-AFU15 study, patients were stratified at randomization according to the use of prior hormonal therapy, use of prior chemotherapy treatment, and Glass prognostic group (poor, intermediate, and good) [11]. For the GETUG-AFU15 study, a post hoc analysis was performed, through chart review, to distinguish between patients with HV and LV disease defined by the same criteria as CHAARTED.

2.1. Statistical analysis

The main objective of our study was to conduct a post hoc analysis to assess the OS benefit of ADT plus D and ADT alone in specific subgroups of patients from the CHAARTED and GETUG-AFU15 studies, defined by metastatic burden (HV or LV) and time of metastasis occurrence (at diagnosis or after failure of local therapy). The main baseline characteristics evaluated in both trials were summarized using standard descriptive statistics (median and interquartile range for continuous variables, and frequency and percentages for categorical variables). Prior to analysis, patients not known to have died were censored at the date of the last known follow-up evaluation. OS data from these two studies were first analyzed separately to estimate the HRs between the ADT + D and ADT arms in the specific subgroups. As per protocol, HRs with 95% CIs were derived from Cox regression analysis that adjusted for stratification factors in the randomization processes for both trials. To increase the ability to assess the OS benefit from adding D to ADT in specific subgroups, a fixed-effect meta-analysis model was used to combine the HRs from each study. Essentially, the meta-analysis model estimated a pooled HR as a weighted average of the individual HRs where each HR is weighted by the reciprocal of its standard error estimate. Meta-analysis results were used to assess the homogeneity in pooled HRs according to metastatic burden (HV and LV) and timing of metastasis occurrence (after prior local treatment [PRLT] or de novo metastasis) separately. Cox regression analysis was performed using the SAS Software v9.3 PHREG procedure (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Meta-analysis was performed in R 3.3.1 software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; http://www.R-project.org) using the package meta.

3. Results

3.1. Patient characteristics and OS analysis in CHAARTED and GETUG-AFU15 trials

In total, 790 and 385 patients were randomized in the CHAARTED and GETUG-AFU15 studies, respectively, with respective median follow-up periods of 48.2 and 83.2 mo in patients who survived. Their main baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Patients from CHAARTED and GETUG-AFU15 were different with regard to percentages of ECOG performance status 0, HV disease, Gleason score ≥8, and median PSA levels. Statistically significant difference in OS between the ADT + D and ADT arms was found in the CHAARTED study (median 57.6 vs 47.2 mo; HR [95% CI] 0.73 [0.59; 0.89], p = 0.002), but not in the GETUG-AFU15 (median 62.1 vs 48.6 mo; HR [95% CI] 0.88 [0.68; 1.14], p = 0.3). Although ADT + D versus ADT effect size was less pronounced in GETUG-AFU15, the difference in log(HR) between both trials did not meet conventional levels of statistical significance (p = 0.07), and the pooled average effect size estimated from both trials reached statistical significance (HR [95% CI] 0.79 [0.67; 0.93], p = 0.004).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients randomized in the CHAARTED and GETUG-AFU15 studies

| CHAARTED, n = 790 | GETUG-AFU15, n = 385 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| ADT + D, n = 397 | ADT alone, n = 393 | ADT + D, n = 192 | ADT alone, n = 193 | |

| Age (yr), median (IQR) | 64 (57–69) | 63 (56–69) | 63 (57–68) | 64 (58–70) |

| ECOG PS, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 277 (70) | 272 (69) | 181 (99) | 176 (96) |

| 1–2 | 120 (30) | 121 (31) | 2 (0.01) | 7 (3.8) |

| Volume of metastases, n (%) | ||||

| Low | 134 (34) | 143 (36) | 100 (52) | 102 (53) |

| High | 263 (66) | 250 (64) | 92 (48) | 91 (47) |

| Visceral metastases, n (%) | 57 (14) | 66 (17) | 28 (15) | 23 (12) |

| Prior local treatment for prostate cancer a, n (%) | 108 (27) | 106 (27) | 62 (33) | 46 (24) |

| Metastases at diagnosis | 289 (73) | 286 (73) | 128 (67) | 144 (76) |

| Gleason score, n (%) | ||||

| ≤6 | 21 (5.3) | 21 (5.3) | 18 (9) | 14 (7) |

| 7 | 96 (24) | 83 (21) | 66 (34) | 64 (33) |

| 8–10 | 241 (61) | 243 (62) | 103 (54) | 113 (59) |

| Unknown | 39 (10) | 46 (12) | 5 (2.6) | 2 (0.01) |

| PSA (ng/ml) b, median (IQR) | 51 (12–255) | 52 (14–295) | 27 (5–106) | 26 (5–126) |

| Study period | 2006–2012 | 2004–2008 | ||

ADT = androgen deprivation therapy; D = docetaxel; ECOG PS = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; IQR = interquartile range; PSA = prostate-specific antigen.

Primary radiation or prostatectomy.

At the start of ADT in CHAARTED, at baseline evaluation in GETUG-AFU15.

3.2. Subgroup analysis based on metastatic burden

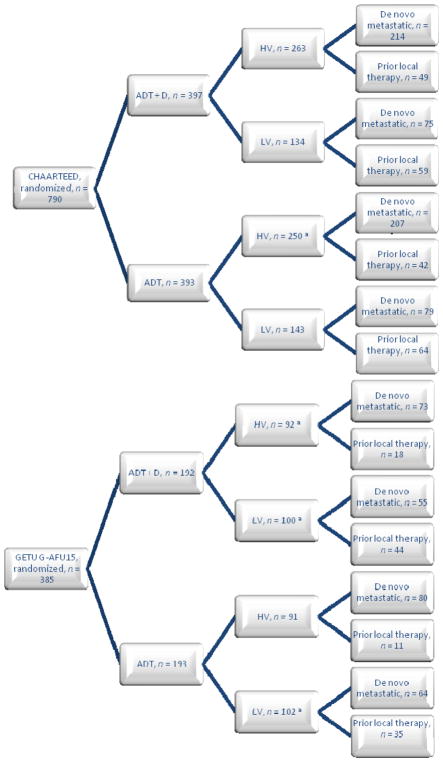

The first classification level for subgroup analysis was based on metastatic burden (Fig. 1). In both trials, median OS was consistently longer in the ADT + D arms compared with the ADT arms (Table 2). Differences in study-specific log(HRs) showed no significant difference in any of the subgroups analyzed in the two studies (Table 2). In other words, there was no heterogeneity between CHAARTED and GETUG-AFU15 in the HV (p = 0.3) or LV (p > 0.9) subgroups. Meta-analysis results of the aggregate data of the two studies revealed significant heterogeneity in ADT + D versus ADT effect sizes between HV and LV subgroups (p = 0.017), with pooled average HR estimates in HV and LV patients of 0.68 ([95% CI 0.56; 0.82], p < 0.001) and 1.03 ([95% CI 0.77; 1.38], p = 0.8), respectively. The survival figures of the control arms (ADT alone) were similar in both studies, both for all randomized patients and for the HV subgroup, whereas in the ADT + D arms, median OS was much shorter for the HV subgroup in the GETUG-AFU15 study (39.8 vs 51.2 mo in CHAARTED).

Fig. 1.

Disposition of patients in the CHAARTED and GETUG-AFU15 studies.

ADT = androgen deprivation therapy; D = docetaxel; HV = high volume; LV = low volume.

aIncluding nonevaluable patients.

Table 2.

Median and 95% CI overall survival (in months) in the overall population and prespecified subgroups

| Overall population | HV | LV | p value a | Upfront | PRLT | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 790 | N = 513 | N = 277 | N = 575 | N = 214 | |||

|

|

|||||||

| CHAARTED | ADT + D | 57.6 | 51.2 | 63.5 | 52 | 67.4 | |

| (52; 63.9) | (45.2; 58.1) | (58.3; 78.5) | (45.5, 58.1) | (59, 74.3) | |||

| ADT alone | 47.2 | 34.4 | NR | 39.5 | NR | ||

| (41.8; 52.8) | (30.1; 42.1) | (59.8; NR) | (32.4; 45.2) | (57.6; NR) | |||

| N = 385 | N = 183 | N = 202 | N = 272 | N = 108 | |||

|

|

|||||||

| GETUG-AFU15 | ADT + D | 62.1 | 39.8 | NR | 52.6 | NR | |

| (49.5; 73.7) | (28; 53.4) | (69.5; NR) | (43.3; 66.8) | (69.5; NR) | |||

| ADT alone | 48.6 | 35.1 | 83.4 | 41.5 | 69.8 | ||

| (40.9; 60.6) | (29.9; 43.6) | (61.8; NR) | (36.3; 54.5) | (62.2; NR) | |||

| Pooled average HR (95% CI), p value c | 0.79 | 0.68 | 1.03 | 0.017 | 0.76 | 0.9 | |

| (0.67; 0.93) | (0.56; 0.82) | (0.77; 1.38) | (0.63; 0.92) | (0.61; 1.33) | |||

| 0.004 | <0.001 | 0.8 | 0.004 | 0.6 | |||

| p value d | 0.07 | 0.3 | >0.9 | 0.1 | 0.7 | ||

ADT = androgen deprivation therapy; CI = confidence interval; D = docetaxel; HR = hazard ratio; HV = high volume; LV = low volume; NR = not reported; PRLT = prior local treatment.

p value for difference in log(HR) between HV and LV subgroups based on aggregated data.

p value for difference in log(HR) between upfront and PRLT subgroups based on aggregated data.

Pooled average HR (95% CI) and p value using inverse variance weights.

p value for difference in log(HR) between CHAARTED and GETUG-AFU15 in the overall population and in subgroups.

3.3. Subgroup analysis based on time of metastasis occurrence

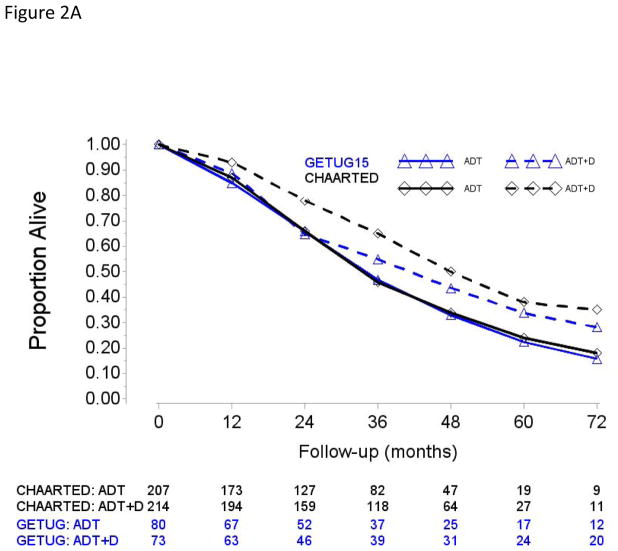

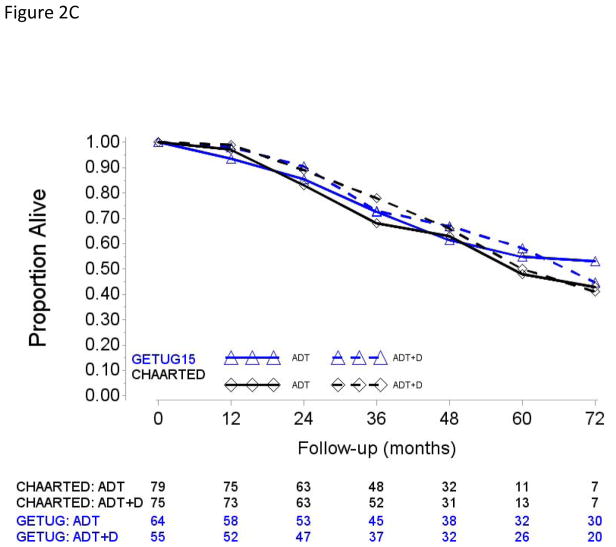

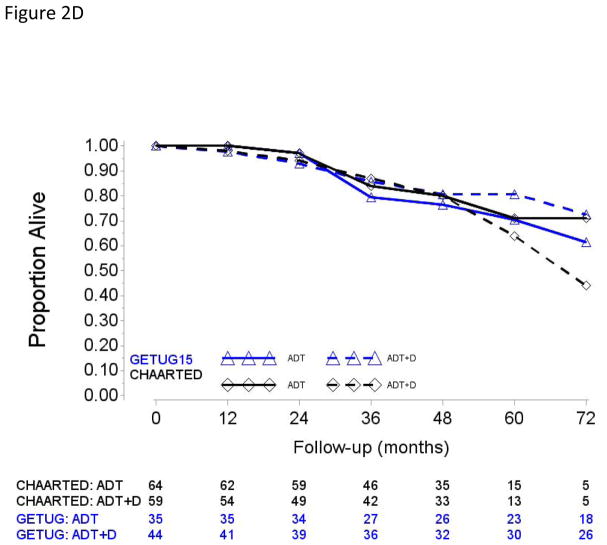

A majority of patients presented with metastatic disease at diagnosis, namely 575 (72.8%) in the CHAARTED study and 272 (70.6%) in the GETUG-AFU15 study (Fig. 1). Patients with PRLT had longer OS than those with de novo metastases (upfront; Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Overall survival in (A) patients with high-volume disease and metastases at initial diagnosis of prostate cancer, (B) patients with high-volume disease and prior local treatment (no metastases at initial diagnosis of prostate cancer), (C) patients with low-volume disease and metastases at initial diagnosis of prostate cancer, and (D) patients with low-volume disease and prior local treatment (no metastases at initial diagnosis of prostate cancer).

ADT = androgen deprivation therapy; D = docetaxel.

In both subgroups, differences in study-specific ADT + D versus ADT-alone HRs and pooled HRs did not meet conventional level of statistical evidence (Table 2). We further explored ADT + D versus ADT effect sizes between PRLT and upfront conditions in the HV and LV subgroups separately (Supplementary Table 1). Pooled HRs showed significant improvement in OS from ADT + D only in patients with HV disease and de novo metastases (HR [95% CI] 0.67 [0.55;0.83]). Pooled HRs limited to the LV patients suggested no apparent survival value of adding D to ADT, irrespective of whether patients received ADT + D with de novo metastatic/presented upfront with metastases (HR [95% CI] 1 [0.70;1.44]) or after PRLT (HR [95% CI] 1.12 [0.66;1.90]).

4. Discussion

Resistance to ADT occurs in most patients, after 24–36 mo [18]. Many unsuccessful attempts of various strategies have been made to improve the outcomes, before the publication of positive results in the CHAARTED and STAMPEDE trials led many authors to claim that D + ADT should be the first-line standard of care in this population. The GETUG-AFU15 study yielded apparently contradictory results with a nonsignificant OS improvement not only in the overall population, but also in the HV subgroup. The possible reasons of this apparent contradiction have extensively been discussed in previous papers [19]. They include a possible lack of power of the French study, due to the small size of the cohort and the underestimated OS in the ADT arm that drove the baseline statistical hypotheses, a higher percentage of patients with HV disease in CHAARTED, differences in patients’ profiles with more patients in CHAARTED with a poorer prognosis (a lower proportion of patients with ECOG 0, a higher proportion of patients with high Gleason scores, different periods of inclusion, and higher PSA levels), and different management of patients after progression: in CHAARTED, more patients in the ADT + D arm received a greater number and various types of life-extending drugs, while in GETUG-AFU15, a higher percentage of patients from the ADT arm received salvage D compared with CHAARTED. Indeed, in the GETUG-AFU15 study, 127 of 149 patients (85%) from the ADT arm treated for progressive disease received D (91% in the HV disease and 78% in the LV disease subgroup). Other treatments administered after progression were abiraterone acetate (36 and 33 in the ADT and ADT plus D arms, respectively), cabazitaxel (15 and 16 patients, respectively), and enzalutamide (12 and 15 patients, respectively). As detailed in the supplementary material of the first survival analysis of the CHAARTED trial [10],, of the 238 patients who had progressed on ADT plus D, 150 had received one or more of D, cabazitaxel, abiraterone, or enzalutamide, and of 287 ADT-alone patients who had progressed, 187 patients had received one or more of these agents. Another hypothesis is that different presentations and volume of disease may represent different biology, and therefore result in one group benefitting from a given therapy while other groups may not benefit from a given therapy. It is possible that de novo and/or HV metastatic disease reflects a more aggressive type of prostate cancer, more likely to benefit from early chemotherapy, whereas patients with a more indolent course may do just as well with sequential therapy at the time of CRPC as they can be salvaged more effectively. In the present analysis, we account for both of these parameters. Using the aggregate data and performing tests of heterogeneity, it is shown that the benefits of D added to ADT were seen only in patients with HV disease and de novo metastases. This was shown in the individual analysis of the CHAARTED study. In the GETUG-AFU15 study, patients from this subgroup randomized into the ADT + D arm experienced nonsignificant 9.6-mo improvement in median OS compared with those randomized in the ADT group. These findings can be interpreted in two different ways. Either the benefits of D exist in all patient categories, but they could not be demonstrated because of small-size subgroups (apart from de novo metastatic, HV patients in the CHAARTED study, all subgroups comprised <80 patients) due to insufficient power or because of insufficient follow-up in patients with good prognosis (LV disease and PRLT). However, with an HR of approximately 1 in the LV subgroups, it is unlikely that a difference would be seen even with larger sample sizes. The other interpretation is that the benefits of D are actually limited to patients with HV disease and de novo metastases, that is, those with more severe and aggressive disease. Only prospective studies will be able to answer this question definitively. The test for heterogeneity being negative in the nonmetastatic versus metastatic cohorts of the STAMPEDE arm could be due to that the high-risk localized patients treated with ADT or ADT + D (with or without radiation having a benefit) have a disease biologically akin to HV de novo metastatic disease that benefits from D. The interim results of GETUG12 [20] and RTOG0521 [21] also suggest a benefit of adding D to ADT plus radiation for high-risk localized disease. In contrast, two studies have shown no benefit of adding D for patients with rising PSA after local therapy [22,23], another component of the M0 subgroup of the STAMPEDE trial. STAMPEDE metastatic patients were not characterized by volume of metastases. The findings from the aggregate data presented here, where volume of disease was annotated, show a heterogeneous outcome for treatment with D and suggest that the disease course of patients with LV disease is more closely aligned with that of patients with disease not seen on scans but evident by rising PSA, an even earlier version of LV disease. In short, the totality of the data shows that different subgroups of patients with mCNPC have different prognoses and this would suggest that they may need different treatments. For example, patients with HV disease have a poorer prognosis and the only group to have clear benefit with early D. Future clinical trials should consider categorizing patients into prognostic subgroups, based on PRLT and volume of metastases, according to the clearly different clinical outcomes obtained in the ADT-alone arms: good prognosis for those with PRLT and LV disease; intermediate prognosis for those with PRLT and HV disease, or those with LV disease and de novo metastases; and poor prognosis for those with de novo HV disease. Moreover, since abiraterone acetate has recently demonstrated significant OS benefits in patients with mCNPC [24,25], these future studies will hopefully also determine the respective role of D, abiraterone acetate, or both, and identify the subgroups of patients for whom these various strategies are most appropriate. The population eligible for early D must be thoroughly defined in order to avoid unnecessary toxicities in patients with a disease with a longer natural history. Sixteen toxic deaths were identified in the three randomized trials [15], which is quite low when considering the total number (N = 1774) of patients who received ADT plus D, but unacceptable in patients with good prognosis and long life expectancy. Non–life-threatening toxicity is also important to consider. Docetaxel may lead to diarrhea, fatigue, gastrointestinal disorders, neuropathy, neutropenia, and infections. In GETUG-AFU15, 21% of patients discontinued D due to toxicity [11]. In the STAMPEDE study, 52% of patients in the ADT + D arm (whether metastatic or not) experienced grade ≥3 adverse events [12]. In CHAARTED, 16.7% and 12.6% of patients reported grade 3 and grade 4 adverse events, respectively. Importantly, these toxicities may misrepresent the patient experience, as patient-reported outcomes suggest a higher frequency and intensity of symptoms experienced during treatment [26].

The population included in these studies may not reflect the real-life situation exactly. In the USA, it has been shown from national databases that the percentage of patients with de novo metastases was below 5% of all prostate cancer diagnoses, but account for about one-third of prostate cancer deaths in recent years [27]. A retrospective analysis of another US multi-institutional patient database showed that 2.8% of patients had M1 disease at diagnosis (bone 77%, visceral 38%, and lymph nodes 21%) [28].

The inherent limitations of this analysis are that the post hoc combined aggregate analysis precludes the use of uniform definitions of progression, eligibility criteria, and scheduled assessments. Moreover, the two trials were conducted in two distinct regions and eras with different access to life-prolonging therapies for CRPC. As detailed in our statistical analyses, we have assessed for heterogeneity between subgroups and between the trials in an attempt to assess for differences and consistency across the trials. It is always difficult to draw definitive conclusions from post hoc analyses, which may lead to multiple unplanned subgroups and, by their very nature, are hypothesis generating, which need confirmation from prospective trials. It is clear that metastatic burden, whatever its definition, is an important prognostic factor that should be considered for the choice of early D. In short, analysis of the aggregate data from these two trials presented in this paper did not show evidence of heterogeneity for the effect of D across both trials. However, there was heterogeneity of effect of D between HV and LV within CHAARTED, and the aggregate data of both studies with D leading to improvement in OS for the HV but not the LV. However, other factors, still unknown, are also probably involved; we need to increase our knowledge of these factors to better individualize the treatment of metastatic prostate cancer because one size does not fit all.

5. Conclusions

The combined analyses of the CHAARTED and GETUG-AFU15 data support the observation that HV and LV behaved differently in terms of OS with ADT alone and impact of D. It is also clear that some patients benefit from D in the setting of mCNPC, namely, those with a poorer prognosis such as a high tumor burden, which is still to be better defined. At the other end of the spectrum, patients with LV disease, slow-growing tumors, have less benefit with early chemotherapy, and the toxicity may often exceed the benefits. However, going forward, we need to develop better tools than volume of metastases on conventional imaging and explore modern technologies to identify better molecular or novel imaging parameters, and accurately characterize each patient’s disease so we can optimize treatment allocation to D-based and/or abiraterone-based and/or possibly other biologically directed therapy combinations with ADT for mCNPC.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support and role of the sponsor: Partial financial support and drug supply by Sanofi. For the E3805: CHAARTED: Sanofi provided docetaxel for early use and financial grant support; NCI-CTEP and ECOG-ACRIN; Public Health Service Grants CA180794, CA180820, CA23318, CA66636, CA21115, CA49883, CA16116, CA21076, CA27525, CA13650, CA14548, CA35421, CA32102, CA31946, CA04919, CA107868, and support from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health and the Department of Health and Human Services. For the GETUG-AFU15: trial was supported by grants from The French Health Ministry (PHRC), Sanofi-Aventis, Astra-Zeneca, and AMGEN.

Financial disclosures

Gwenaelle Gravis certifies that all conflicts of interest, including specific financial interests and relationships and affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript (eg, employment/affiliation, grants or funding, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, royalties, or patents filed, received, or pending), are the following: Gwenaelle Gravis: travel, accommodations, expenses—Janssen Oncology, Pfizer, and Roche. Jean-Marie Boher, Yu-Hui Chen, Glenn Liu: no relationships to disclose. Karim Fizazi: honoraria—Astellas Pharma, Janssen, Sanofi, and Takeda; consulting or advisory role—Astellas Pharma, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Curevac, ESSA, Janssen Oncology, Orion Pharma GmbH, Roche/Genentech, and Sanofi; travel, accommodations, expenses—Amgen. Michael Anthony Carducci: consulting or advisory role—Astellas Pharma, AstraZeneca, Clovis Oncology, Medivation, and Merck. Stephane Oudard: honoraria—Astellas Pharma, Bayer, Janssen, and Sanofi; consulting or advisory role—Astellas Pharma, Bayer, Janssen Oncology, and Sanofi. Florence Joly: consulting or advisory role—AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, and Tesaro; research funding—Astellas Medivation; expert testimony—Roche and Sanofi. David Frazier Jarrard and Michel Soulie: no relationships to disclose. Mario A. Eisenberger: honoraria—Sanofi; consulting or advisory role—Astellas Pharma, Bayer, Ipsen, Sanofi; research funding—Genentech, Sanofi, and Tokai Pharmaceuticals; travel, accommodations, expenses—Astellas Pharma, Bayer, and Sanofi. Muriel Habibian: no relationships to disclose. Robert Dreicer: honoraria—Astellas Pharma; consulting or advisory role—Asana Biosciences, Astellas Pharma, Exelixis, Ferring, Janssen Oncology, Medivation, and Roche; research funding—Asana Biosciences (Inst) and Genentech (Inst). Jorge A. Garcia: consulting or advisory role—Bayer, Eisai, Exelixis, Genentech/Roche, Medivation, Pfizer, and Sanofi; speakers’ bureau—Bayer, Genentech/Roche, Medivation/Astellas, and Sanofi; research funding—Astellas Pharma (Inst), Bayer (Inst), Genentech/Roche (Inst), Janssen Oncology (Inst), Lilly (Inst), Orion Pharma GmbH (Inst), and Pfizer (Inst); travel, accommodations, expenses—Bayer, Eisai, Exelixis, Genentech/Roche, Medivation/Astellas, Pfizer, and Sanofi. Maha Hussain: consulting or advisory role—AstraZeneca, Essa, Johnson & Johnson, and Synthon; research funding—Astellas Pharma (Inst), Bayer (Inst), Genentech (Inst), Medivation (Inst), and Pfizer (Inst); patents, royalties, other intellectual property—title: Dual Inhibition of MET and VEGF for the treatment of castration resistant prostate cancer and osteoblastic bone metastases, applicant/proprietor Exelexis, Inc., application no./patent no. 11764665.4-1464 Application No/Pat; title: Method of treating cancer, docket no.: serial number: 224990/10-016P2/311733 61/481/671, application filed on: 5/2/2011; title: Systems and methods for tissue imaging, 3676, our file: serial number: UM-14437/US-1/PRO 60/923,385 UM-14437/US-2/ORD 12/101,753. Manish Kohli: no relationships to disclose. Nicholas J. Vogelzang: employment—US Oncology; stock and other ownership interests—Caris Life Sciences; honoraria—Abbvie, Bavarian Nordic, DAVA Oncology, Dendreon, Endocyte, Janssen Oncology, Mannkind, Pfizer, and UpToDate; consulting or advisory role—Amgen, AVEO, Bayer, BIND Biosciences, Cerulean Pharma, Churchill Pharmaceuticals, Genentech/Roche, HERON, Janssen Biotech, Labceutics, and Pfizer; speakers’ bureau—Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Caris MPI, Dendreon, Genentech/Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, Medivation, Millennium, Pfizer, and Sanofi; research funding—Endocyte (Inst), Exelixis (Inst), GlaxoSmithKline (Inst), Merck (Inst), Parexel (Inst), Progenics (Inst), US Oncology (Inst), and Viamet Pharmaceuticals (Inst); travel, accommodations, expenses—Bayer/Onyx, Celgene, Dendreon, Exelixis, Genentech/Roche, Novartis, Pfizer, and US Oncology. Joel Picus: consulting or advisory role—Novo Nordisk; research funding—Agensys, Altor BioScience, Astex Pharmaceuticals, BioClin Therapeutics, Mirati Therapeutics, Novartis, and Oncogenex. Robert S. DiPaola: research funding—Abbvie (Inst). Christopher Sweeney: stock and other ownership interests—Leuchemix; consulting or advisory role—Astellas Pharma, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Genentech/Roche, Janssen Biotech, Pfizer, and Sanofi; research funding—Astellas Pharma (Inst), Bayer (Inst), Exelixis (Inst), Janssen Biotech (Inst), and Sanofi (Inst); patents, royalties, other intellectual property—Leuchemix: parthenolide, dimethylaminoparthenolide; Exelixis: abiraterone plus cabozantinib combination.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Gwenaelle Gravis had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Gravis, Boher, Chen, Liu, Fizazi, Carducci, Jarrard, Dreicer, Garcia, Hussain, DiPaola, Sweeney.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis and interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Statistical analysis: Boher, Chen.

Obtaining funding: Gravis, Liu, Carducci, Jarrard, Eisenberger, Habibian, Dreicer, Garcia, Hussain, Kohli, Vogelzang, Picus, Sweeney.

Administrative, technical, or material support: None.

Supervision: None.

Other: None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could aect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.International Agency for Research on Cancer. Prostate cancer: estimated incidence, mortality and prevalence worldwide. 2012 http://globocan.iarc.fr/Pages/fact_sheets_cancer.aspx.

- 2.Institut National du Cancer. Les cancers en France/edition 2015. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petrylak DP, Tangen CM, Hussain MH, et al. Docetaxel and estramustine compared with mitoxantrone and prednisone for advanced refractory prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1513–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tannock IF, de Wit R, Berry WR, et al. Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1502–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Bono JS, Oudard S, Ozguroglu M, et al. Prednisone plus cabazitaxel or mitoxantrone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel treatment: a randomised open-label trial. Lancet. 2010;376:1147–54. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61389-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scher HI, Fizazi K, Saad F, et al. Increased survival with enzalutamide in prostate cancer after chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1187–97. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1207506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fizazi K, Scher HI, Molina A, et al. Abiraterone acetate for treatment of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: final overall survival analysis of the COU-AA-301 randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:983–92. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70379-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beer TM, Tombal B. Enzalutamide in metastatic prostate cancer before chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1755–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1410239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ryan CJ, Smith MR, Fizazi K, et al. Abiraterone acetate plus prednisone versus placebo plus prednisone in chemotherapy-naive men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (COU-AA-302): final overall survival analysis of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:152–60. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71205-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sweeney CJ, Chen YH, Carducci M, et al. Chemohormonal therapy in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:737–46. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1503747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gravis G, Fizazi K, Joly F, et al. Androgen-deprivation therapy alone or with docetaxel in non-castrate metastatic prostate cancer (GETUG-AFU 15): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:149–58. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70560-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.James ND, Sydes MR, Clarke NW, et al. Addition of docetaxel, zoledronic acid, or both to first-line long-term hormone therapy in prostate cancer (STAMPEDE): survival results from an adaptive, multiarm, multistage, platform randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387:1163–77. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01037-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sweeney CC, Liu Y-H, Carducci G, et al. Long term efficacy and QOL data of chemohormonal therapy (C-HT) in low and high volume hormone naïve metastatic prostate cancer (PrCa): E3805 CHAARTED trial. Copenhagen: ESMO; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gravis G, Boher JM, Joly F, et al. Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) plus docetaxel versus ADT alone in metastatic non castrate prostate cancer: impact of metastatic burden and long-term survival analysis of the randomized phase 3 GETUG-AFU15 trial. Eur Urol. 2016;70:256–62. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vale CL, Burdett S, Rydzewska LH, et al. Addition of docetaxel or bisphosphonates to standard of care in men with localised or metastatic, hormone-sensitive prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analyses of aggregate data. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:243–56. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00489-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brawley OW. Trends in prostate cancer in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2012;2012:152–6. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgs035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li J, Djenaba JA, Soman A, Rim SH, Master VA. Recent trends in prostate cancer incidence by age, cancer stage, and grade, the United States, 2001–2007. Prostate Cancer. 2012;2012:691380. doi: 10.1155/2012/691380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eisenberger MA, Blumenstein BA, Crawford ED, et al. Bilateral orchiectomy with or without flutamide for metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1036–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199810083391504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gravis G, Audenet F, Irani J, et al. Chemotherapy in hormone-sensitive metastatic prostate cancer: Evidences and uncertainties from the literature. Cancer Treat Rev. 2017;55:211–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2016.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fizazi K, Faivre L, Lesaunier F, et al. Androgen deprivation therapy plus docetaxel and estramustine versus androgen deprivation therapy alone for high-risk localised prostate cancer (GETUG 12): a phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:787–94. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00011-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sandler HH, Rosenthal C, Sartor SA, et al. A phase III protocol of androgen suppression (AS) and 3DCRT/IMRT versus AS and 3DCRT/IMRT followed by chemotherapy (CT) with docetaxel and prednisone for localized, high-risk prostate cancer (RTOG 0521) J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(Suppl):LBA5002. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oudard SL, Caty I, Miglianico A, et al. Docetaxel (D) with androgen suppression (AS) for high-risk localized prostate cancer (HrPC) patients (pts) who relapsed PSA after radical prostatectomy (RP) and/or radiotherapy (RT): a randomized phase III trial. ESMO. 2017 Abstr 7840. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morris MJ, Hilden P, Gleave ME, et al. Efficacy analysis of a phase III study of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) +/− docetaxel (D) for men with biochemical relapse (BCR) after prostatectomy. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(Suppl):5011. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fizazi K, Tran N, Fein L, et al. Abiraterone plus Prednisone in metastatic, castration-sensitive prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:352–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1704174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.James ND, de Bono JS, Spears MR, et al. Abiraterone for prostate cancer not previously treated with hormone therapy. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:338–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1702900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gravis G, Marino P, Joly F, et al. Patients’ self-assessment versus investigators’ evaluation in a phase III trial in non-castrate metastatic prostate cancer (GETUG-AFU 15) Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:953–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Flaig TW, Potluri RC, Ng Y, Todd MB, Mehra M, Higano CS. Disease and treatment characteristics of men diagnosed with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer in real life: analysis from a commercial claims database. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2017;15:273–9 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.