Abstract

Lanthanide-doped upconversion nanoparticles (UCNPs) are capable of converting near-infra-red excitation into visible and ultraviolet emission. Their unique optical properties have advanced a broad range of applications, such as fluorescent microscopy, deep-tissue bioimaging, nanomedicine, optogenetics, security labelling and volumetric display. However, the constraint of concentration quenching on upconversion luminescence has hampered the nanoscience community to develop bright UCNPs with a large number of dopants. This review surveys recent advances in developing highly doped UCNPs, highlights the strategies that bypass the concentration quenching effect, and discusses new optical properties as well as emerging applications enabled by these nanoparticles.

Introduction

Upconversion nanoparticles (UCNPs) are a unique class of optical nanomaterials doped with lanthanide ions featuring a wealth of electronic transitions within the 4f electron shells. These nanoparticles can up-convert two or more lower-energy photons into one high-energy photon1–3. Over the past decade, this unique anti-Stokes optical property has enabled a broad range of applications, spanning from background-free biological sensing and light-triggered drug delivery to solar energy harvesting and super-resolution microscopy4–6. To achieve high upconversion efficiency, it is essential to co-dope sensitizer ions alongside activator ions that have a closely matched intermediate-excited state7–9. This doping process requires a rational design that offers optimal interactions of a network of the sensitizer and activator ions, and the upconversion efficiency is highly dependent on the separating distance between the dopants. Therefore, the proper management of the doping concentration in a given nanoparticle will be the deciding factor in leveraging the energy transfer process and ultimately the luminescence performance of the nanoparticle9–11.

In stark contrast to quantum dots, UCNPs contain individual and variable absorption and emission centres. Thus, the primary goal to increase the concentration of co-dopants in UCNPs is to directly improve their brightness. However, the constraint of concentration quenching that limits the amount of the dopants usable has been known for years in bulk materials (for example, Nd3+-doped YAG laser crystals)12, and tuning the luminescence properties has been largely hindered at relatively low-doping concentrations2,13. For nanomaterials with a high ratio of surface area to volume, high-doping concentration is likely to induce both cross-relaxation energy loss and energy migration to the surface quenchers. This, in turn, explains the much reduced luminescence quantum yield in upconversion nanomaterials relative to their bulk counterparts14–16. Encouragingly, over the past decade, a great deal of research efforts has been devoted to the study of the concentration quenching mechanisms2,10,17,18, thereby opening the door to many ground-breaking applications.

In this review, we discuss the phenomenon and underlying mechanism of concentration quenching occurring in UCNPs, review the general and emerging strategies for overcoming the concentration quenching effect, and summarize the impact of highly doped UCNPs on a range of disruptive applications. In particular, we discuss the rational design of heterogeneously doped, multilayered UCNPs that allow us to precisely control the energy migration process and induce cross-relaxation between the dopants for unprecedented optical phenomena. We present the challenges and opportunities of the doping strategies in developing smaller and brighter nanoparticles as well as hybrid materials with synergetic multifunction.

Concentration quenching

For a very long time, the problem of concentration quenching was the major obstacle that hindered the quest for highly luminescent materials12,19. The theory of concentration quenching in inorganic phosphors was introduced in 1954 by Dexter and Schulman, who pointed out that considerable quenching of luminescence in bulk materials arises when the activator concentration reaches 10−3–10−2 M[19]. Different mechanisms (resonance energy transfer20, molecular interactions21, and intermolecular photo-induced electron transfer22) of concentration quenching in organic dyes have been studied since the early 1980s. The issue has limited the maximum number of fluorophores allowed in dye-doped silica nanoparticles23. As a result, the detrimental effect of concentration quenching in luminescent materials imposes a restriction on access to a high level of luminescence intensity, in consequence hindering their further applications.

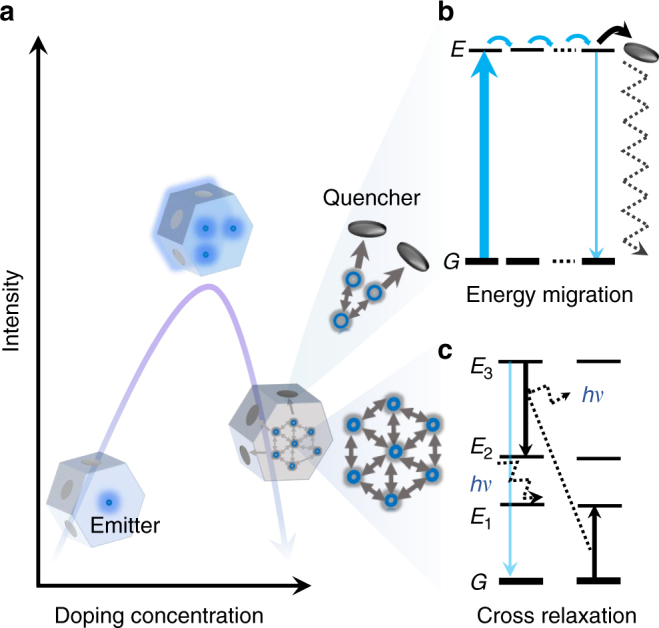

The limitation set by the threshold of concentration quenching becomes a real problem for nanoscale luminescent materials (Figure 1a). As illustrated in Figure 1b, c, the general cause follows that high-doping concentration (shorter distance) leads to increased occurrence of energy transfer process between the dopants5,7. The excited-state electrons can be quickly short-circuited to the surface of nanomaterials, where a relatively large number of quenchers exist. Therefore, a dramatic decrease in luminescence intensity is observed. More specifically, the high-doping concentration facilitates both the energy migration of excited levels (typically within the sensitizer-sensitizer network) to the surface quenchers (Figure 1b)15,24,25 and the inter-dopant (typically between activators) cross-relaxation that causes emission intensity loss each time7,13 (Figure 1c).

Fig. 1.

Concentration quenching in upconversion nanoparticles. a Increasing the doping concentration of dopant ions in the nanoparticles increases the number of photon sensitizers and emitters, shortens the distance from sensitizer to activator, and hence enhances the emission brightness, but surpassing a concentration threshold could make the cascade energy transfer process less effective, as the concentration quenching dominates with high levels of dopants. In a highly doped system, the concentration quenching is likely to be induced by: b non-radiative energy migration to surface quenchers and c cross-relaxation non-radiative energy loss. The term hv represents the phonon energy

To avoid the quenching of luminescence, conventionally, the doping level has been kept relatively low to ensure a sizable separation between the dopants to prevent parasitic interaction. Accordingly, the critical distance (Förster critical distance) is typically in the range of 2−6 nm26, meaning that the doping range should remain below 10−3 M for organic dye-doped SiO223 and 10−2 M for UCNPs (Box 1)13. For an efficient upconversion to proceed, the relatively low concentrations of sensitizers (typically around 20 mol %) and activators (below 2 mol %) are generally used in the hexagonal-phase alkaline rare-earth fluoride nanocrystal, β-AREF4, that is known as one of the most efficient host material for upconversion. Low-doping concentration is the key roadblock to yield smaller and brighter luminescent nanomaterials27–29, which requires a canonical approach to optimizing the composition and chemical architecture of nanoparticles as well as photoexcitation schemes4,6.

Box 1. The mechanism of concentration quenching

The notorious photophysical phenomenon of concentration quenching is frequently observed in solutions containing a high concentration of organic dyes, typically in the range of 10−3–10−2 M7,9,19,20. The leading factors for concentration quenching involve Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) and Dexter electron transfer (DET). FRET is based on classical dipole–dipole interactions between the transition dipoles of the donor (D) and acceptor (A). The rate of the energy transfer decreases with the D–A distance, R, falling off at a rate of 1/R6. DET is a short-range phenomenon that falls off exponentially with distance (proportional to e−kR, where k is a constant that depends on the inverse of the van der Waals radius of the atom) and depends on spatial overlap of donor and quencher molecular orbitals16. The concentration quenching for phosphors is expressed by the rate constant, kCQ, determined from the equation for ηPL:30

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

where TPL is the intrinsic radiative decay time of the D, R is the distance between D–A and R0 is the Förster radius at which the energy transfer efficiency between D and A falls to 50%, ηet is the energy transfer efficiency, ηisc is the intersystem crossing efficiency, kph and knr are the rate constants of radiative and non-radiative decay, respectively.

When this analogy extends to an inorganic system, such as UCNPs, the concentration quenching denotes the emission intensity decrease phenomenon as the dopant concentration is too high. Typically, the UCNPs contain two types of lanthanide dopants, that is, the sensitizer (D) and activator/emitter (A)2,7. Though some singly doped (for example Er3+) particles can generate upconversion, researchers prefer to employ a sensitizer (for example Yb3+) to enlarge the absorbance in the NIR for enhanced upconversion luminescence. The process of the energy extraction from a sensitizer to an acceptor usually takes place via a non-radiative exchange (DET) or a multipolar interaction (FRET)31.

Most of the lanthanides have plentiful excited states, which show a high possibility to couple with one another through multipolar interactions with matching energy gaps, known as cross-relaxation (Fig. 1c)7. But this kind of coupling effect only occurs when the doping concentration is above a certain threshold. Because the 4f–4f transitions are symmetry forbidden according to the Laporte selection rule, the consequences are low intensity and long-decay time32,33. This cross-relaxation is primarily responsible for concentration quenching because neighbour ions, one in the excited state and the other in the ground state, non-radiatively exchange energy generally followed by phonon relaxation. The cross-relaxation process is evidenced by shorter lifetimes and decreased luminescence intensity.

Considering the energy transfer between two, or a network of, identical ions (for example, Yb3+ ions) in a concentrated system, the excited electrons will hop among the network. Such a process can quickly bring the excitation energy far away from the initial excited sensitizer, known as energy migration (Fig. 1b). In some specific systems, energy migration may be advantageous because it enables the upconversion from Eu3+ or Tb3+ emitters infused with an Gd3+ ion network34, or for Nd3+-based sensitization with the assistance of an Yb3+ ion network35. However, these systems would short-circuit the excitation energy to quenchers.

Emerging strategies to overcome concentration quenching

Recently, great efforts have been made to overcome concentration quenching in luminescent nanoparticles, particularly from the upconversion research community. Various approaches have been developed to alleviate the threshold of concentration quenching in both homogeneously doped nanocrystals and heterogeneously doped core@shell nanocrystals. Box 2 summarizes four strategies that have proven effective for homogeneously doped nanocrystals. One of the most commonly used schemes is to passivate the particle’s surface with an inert shell (for example, NaYF4, NaGdF4, NaLuF4 or CaF2), which can block the pathway of energy migration to surface quenchers15,25,36. The second strategy is to irradiate the particles with a high-energy flux that is sufficient for the activation of all dopant ions37. The third strategy is to choose a host crystal featuring a large unit cell to keep the D–A distance large enough even for stoichiometric compositions24,38. And the last strategy is to improve the doping uniformity in the host nanomaterials36,39, which minimizes the segregation of ions and thus prevents local concentration quenching.

Using wet-chemical synthesis methods developed over the past decade, it becomes possible to accurately control both the number and spatial distribution of dopants. This paves the way for a more efficient synthesis of heterogeneously doped core@multishell nanocrystals, which allows for the optimization of doping concentrations in each layer and selective isolation of different lanthanide ions to lower the probability of deleterious cross-relaxation. For example, Pilch et al. systematically studied a series of core@shell UCNPs to evaluate the effect of core@shell architecture on sensitizer and activator ions40; by separating sensitizers and emitters through the use of multilayer core@shell nanostructures, the concentration quenching threshold of Er3+ was lifted from 2 to 5%41.

Box 2. Main strategies to overcome concentration quenching

a Coating an inert shell: Inert shell passivation on a low-doping luminescent core is a common strategy to avoid surface quenching by shielding the luminescent core from surface quenchers. This strategy further helps highly doped UCNPs by preventing the migration of sensitized photon energy to the surface quenchers, providing a convenient solution for detrimental quenching effects15,25,36,42.

b Increasing excitation power density: In the case of low irradiance, concentration quenching happens in highly doped UCNPs because too many nearby ground-state ions will easily take away the energy of excited-state ions. By supplying a high irradiance, either by using a high-power laser or focusing the excitation beam, a sufficient amount of excitation photon flux will be supplied to the large number of highly doped ions, and the majority of them will be at excited (intermediate) states, which reduces the number of detrimental ground-state ions. This strategy has proven highly effective in alleviating the thresholds of concentration quenching in UCNPs involving Tm3+ or Er3+ as emitters17,18. Benz et al. also described a rate equation model, which shows that the increased luminescence intensity for highly doped nanocrystals at a high irradiance is due to the enlarged distance between excited ions and ground-state ions37.

c Choosing a host nanocrystal with a large unit cell size24,38: The minimum distance between two dopants in a nanocrystal is determined by the size of the unit cell. Taking the β-NaYF4 crystalline structure as an example, the average distance between a sensitizer and an acceptor can be approximated using the following equation: , which is evolved from the known lattice parameters when ignoring the lattice distortion caused by doping31. The parameters x and y represent the doping concentrations of the sensitizer and acceptor, respectively, while a and c are the lattice parameters of the hexagonal unit cells.

d Improving the homogeneous distribution of dopants: A homogeneous distribution of dopants can avoid local concentration quenching. The layer-by-layer hot injection strategy is technically superior to conventional one-pot heating up synthesis procedures in achieving a high uniformity in the dopant distribution43. Precise control on the Angstrom scale of the dopant distribution may be achieved by managing the rate of precursor injection43.

Homogeneously doped nanocrystals

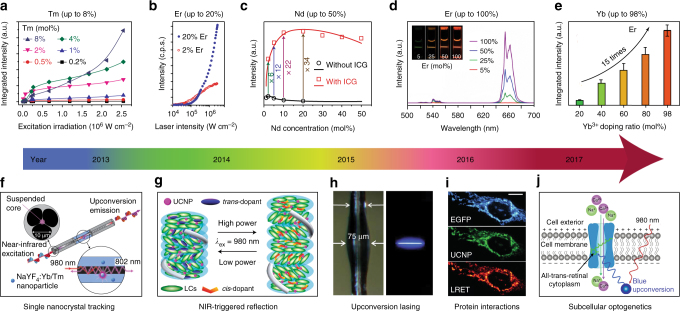

Building brighter nanocrystals: Highly doped homogeneous UCNPs displaying exceptional brightness were first reported by Zhao and coworkers17. As shown in Figure 2a, an increase in the excitation irradiance from 1.6 × 104 to 2.5 × 106 W cm−2 enhances the overall luminescence intensity by a factor of 5.6, 71 and 1105 for 0.5, 4 and 8% Tm3+-doped nanocrystals, respectively17. The high brightness of these Tm3+-doped UCNPs allows the tracking of single nanoparticles in living cells through an optical microscope44. A similar trend was observed in highly Er3+-doped NaYF4:Yb3+ sub-10 nm nanocrystals (Figure 2b). As the excitation power increases, conventional UCNPs (2% Er3+) saturate in brightness while the highly doped UCNPs (20% Er3+) appear much brighter than the conventional UCNPs18. The optimal concentration for Nd3+ (conventionally around 1%) was increased to 20% with the sensitization of indocyanine green (ICG), resulting in about a tenfold brightness enhancement (Figure 2c)45. Encouragingly, the upconversion emission from a series of NaYF4:x%Er3+@NaLuF4 nanocrystals clearly showed high brightness at high-doping concentrations of Er3+, with NaErF4@NaLuF4 (100% doping) being the brightest (Fig. 2d)25.

Fig. 2.

Selected milestones overcoming concentration quenching in homogeneously doped upconversion nanocrystals. a Integrated upconversion luminescence intensity as a function of excitation irradiance for a series of Tm3+-doped (0.2–8%) nanocrystals. Adapted from ref. 17. b Upconversion luminescence intensity of single 8 nm UCNPs with 20 and 2% Er3+, each with 20% Yb3+, plotted as a function of excitation intensity. Adapted from ref. 18. c Experimental results (black circle and red square) and theoretical modelling (black and red curves) of integrated upconversion luminescence intensities of a set of NaYF4:Nd3+ UCNPs with and without indocyanine green (ICG) sensitization. Adapted with permission from ref. 45 Copyright (2016) American Chemical Society. d Luminescence spectra of colloidal dispersion of NaYF4:x%Er@NaLuF4 nanocrystals (x = 5, 25, 50, 100); Inset: luminescence images of NaYF4:x%Er@NaLuF4 in cyclohexane excited with a 980 nm laser. Adapted with permission from ref. 25 Copyright (2017) American Chemical Society. e Integrated upconversion luminescence intensity of α-NaY0.98-xYbxF4:2%Er@CaF2 (x = 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 0.98). Adapted with permission from ref. 47 Copyright (2017) Royal Society of Chemistry. f Schematic of the experimental configuration for capturing upconversion luminescence of NaYF4:Yb3+,Tm3+ nanocrystals using a suspended-core microstructured optical-fibre dip sensor. Adapted from ref. 53. g Upon irradiation by a NIR laser at the high-power density, the reflection wavelength of the photonic superstructure red-shifted, whereas its reverse process occurs upon irradiation by the same laser but with the lower-power density. Adapted with permission from ref. 55 Copyright (2014) American Chemical Society. h Photographs of a microresonator with and without optical excitation. Adapted from ref. 56. i UCNPs functionalized with a nanobody recognizing enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) could rapidly and specifically target to EGFP-tagged fusion proteins in the mitochondrial outer membrane, and this protein interaction process could be detected by lanthanide resonance energy transfer (LRET) in living cells. Scale bar: 10 μm. Reproduced with permission from Drees et al.57 copyright John Wiley and Sons. j Schematic of channelrhodopsin-2 activated in HeLa cells by strong blue upconversion luminescence from NaYbF4:Tm3+@NaYF4 core@shell structure. Adapted with permission from ref. 58 Copyright (2017) American Chemical Society

The optimal concentration of Yb3+ sensitizer ions has also been pushed to its limit. Chen et al. reported that highly Yb3+-doped sub-10 nm cubic phase (α-) NaYF4:Yb3+,Tm3+ nanocrystals display a 43 times emission enhancement at NIR wavelengths compared to the conventional 20% Yb3+-doped one46. With an inert shell coating, the α-NaYbF4:2%Er3+@CaF2 UCNPs display a 15-fold enhancement in visible light emission (Figure 2e)47. Using an inert CaF2 shell, heavy doping of Yb3+ ions in the ultra-small α-NaYF4:Yb3+,Tm3+ and α-NaYbF4:Tb3+ nanoparticles was found to dramatically enhance the upconversion emission for high-contrast bioimaging48–51. With a NaYF4 inert shell, the optimal concentration of Yb3+ sensitizer ions was quantitatively examined by characterizing β-phase UCNPs at the single-particle level52.

Emerging applications: With exceptional brightness and associated optical properties, a range of applications have emerged. For example, highly Tm3+-doped UCNPs enable single nanoparticle sensitivity using a suspended-core microstructured optical-fibre dip sensor (Fig. 2f)17,53. The diverging brightness trends enable the optical encoding application by varying the excitation intensities18. More recently, Li et al. employed living yeast as a natural bio-microlens to concentrate the excitation energy of light and to enhance upconversion luminescence, suggesting a new way of detection of cells54.

High efficiency of upconversion emission from the NIR to the UV was achieved by high Yb3+ doping in NaGdF4:70%Yb3+,1%Tm3+@NaGdF4 nanostructures, and by varying the NIR excitation power density the reversible dynamic red, green and blue reflections of superstructure in a single thin film was demonstrated (Figure 2g)55. Through confined energy migration, an efficient five-photon upconverted UV emission of Tm3+ has been demonstrated in a NaYbF4 host without concentration quenching, and the large amount of spontaneous upconversion emission provides sufficient gain in a micron-sized cavity to generate stimulated lasing emissions in deep-ultraviolet (around 311 nm) wavelength (Figure 2h)56.

Using an increased excitation power density and highly Er3+-doped NaYF4:20%Yb3+,20%Er3+@NaYF4 UCNP, Drees et al. reported that resonance energy transfer has been enhanced by more than two orders of magnitude compared to that of standard NaYF4:20%Yb3+,2%Er3+@NaYF4 particles being excited at a low-power density57. After conjugation with anti-GFP nanobodies, the formed UCNP nanoprobe was used to target GFP fusion proteins inside living cells via a blue upconversion luminescence-induced resonance energy transfer process (Figure 2i)57. More recently, Pliss et al. reported that NaYbF4:0.5%Tm3+@NaYF4 UCNPs emit six times higher blue emission, compared to typical NaYF4:30%Yb3+,0.5%Tm3+@NaYF4 UCNPs, for effective optogenetic activation using NIR light (Figure 2j)58.

Heterogeneously doped nanocrystals

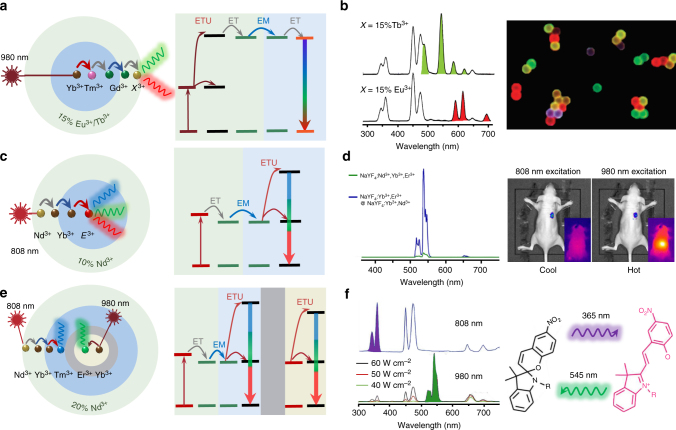

The precision in controlled growth has resulted in a library of intentional heterogeneously doped core@shell UCNPs59,60. The doping concentrations in multilayers of nanostructure can be optimized to satisfy the requirements of a particular application, for example, according to either excitation conditions16,35,61,62 and/or desirable emission wavelengths34,63,64, to produce a high-performance energy-migration-mediated upconversion process (Figure 3)16 or efficient light-to-heat conversion65.

Fig. 3.

Heterogeneously doped core@shell upconversion nanoparticles to overcome concentration quenching. a The schematic of a core@shell design with energy migration at the emission part34. b Upconversion emission spectra with tunable wavelengths attributed to a prescribed Yb3+→Tm3+→Gd3+→Eu3+/Tb3+ energy cascade across the core@shell interface, and luminescence micrograph of polystyrene beads tagged with core@shell nanoparticles. Adapted from ref. 34. c Schematic of the core@shell design with energy migration at the excitation part, E3+ = Er3+, Tm3+, or Ho3+ 35. d Upconversion emission spectra of NaYF4:Yb3+,Er3+@NaYF4:Yb3+,Nd3+ core@shell and homogeneous-doped nanoparticles, and the in vivo imaging of the core@shell nanoparticles under 808 nm and 980 nm excitation, respectively. Adapted with permission from ref. 35 Copyright (2013) American Chemical Society. e Schematic of doping location control in the core@shell design with an energy transfer blocking layer80. f Core@multishell UCNPs (NaYF4:Yb3+,Nd3+,Tm3+@NaYF4@NaYF4:Yb3+,Er3+) with orthogonal emissions under irradiation at 800 and 980 nm, and the orthogonal emissions were employed for reversible isomerization of spiropyran derivatives. Adapted with permissions from Lai et al.80 Copyright John Wiley and Sons

Controlled energy migration: As shown in Figure 3a, the fine-tuning of upconversion emission colours through energy migration has been first demonstrated using a Gd3+ sublattice structure as an efficient energy transfer bridge across the core@shell interface. As shown in Figure 3b, upconversion emission with tunable wavelengths and lifetimes has been realized via a prescribed energy cascade of Yb3+ → Tm3+ → Gd3+ → lanthanide activators (for example, Tb3+, Eu3+, Dy3+ and Sm3+)34. Note that the efficiency of energy-migration-mediated upconversion emission of Tb3+, Eu3+ or Dy3+ at high-doping concentrations is more than two orders of magnitude of that from a Yb3+-sensitized cooperative energy transfer system32. Efficient photon upconversion has also been demonstrated through the heterogeneous core@shell nanostructure of NaYbF4:Gd3+,Tm3+@NaGdF4@CaF2:Ce3+ with a high-doping concentration of Ce3+ in the shell layer66. A CaF2 host has been employed to reduce the 4f–5d excitation frequency of Ce3+ to match the energy level of Gd3+. Zhang et al. have fabricated NaGdF4:Yb3+,Tm3+,Er3+@NaGdF4:Eu3+@NaYF4 incorporated with RGB-emitting lanthanide ions at high concentration, and generated high-brightness white light across the whole visible spectrum67. Notably, apart from the lanthanide ions, organic dyes tethered on the surface of NaGdF4:Yb3+,Tm3+@NaGdF4 nanocrystals can accept the sensitized UV energy through the Gd3+-mediated energy transfer, which can dramatically improve the sensitivity in FRET-limited measurements68. Apart from Gd3+ as the energy mediation ions, due to a large energy gap (ΔE > 5 hν) between respective levels69,70, Mn2+ and Tb3+ ions also show a similar function for energy migration from the core to shell when doped by high concentration of activators.

Exciting UCNPs at 980 nm, through the transparent biological window (650–1350 nm), offers higher photo-biocompatibility and allows deeper tissue penetration than that achievable at 532 nm, as living cells can withstand around 3000 times more intensity at 980 nm than at 532 nm visible excitation71. Considering the fact that water absorbs around 20 times more excitation light at 980 nm than at 800 nm, researchers have further designed core@shell UCNPs by shifting the excitation wavelength to around 800 nm35. The key is to use Nd3+ ions as the sensitizer to absorb 800 nm photons. Because the absorption cross-section of Nd3+ ions at 800 nm is 25-fold larger than that of Yb3+ ions at 980 nm, Nd3+-doped UCNPs display brighter upconversion emissions and negligible overheating effects72. Since homogeneously co-doping high concentration of Nd3+ ions and activators will quench the overall upconversion emission, owing to the deleterious back energy transfer from activators to Nd3+ ions, the doping concentration of Nd3+ has been limited to below 1%. To overcome this threshold, an energy migration system has been employed to separate Nd3+ ions and activators (Figure 3c). Yan et al. first demonstrated high-concentration doping of Nd3+ in core@shell UCNPs that displayed a much enhanced upconversion luminescence relative to those homogeneously doped (Figure 3d). Using these Nd3+-sensitized UCNPs, the authors further demonstrated superior imaging performance for in vivo imaging without the issue of tissue overheating (Figure 3d)35. However, further studies are still needed to investigate the penetration depth trade-off of using 800 nm excitation light, since the amount of light scattering increases in proportion to the fourth power of the frequency of the light. To this regard, a future research direction is to shift the excitation wavelength from the first NIR optical window (650–1000 nm) to the second NIR spectral window (1100–1350 nm), which is ideal for deep-tissue imaging because of reduced water absorption and light scattering73.

To optimize the doping concentration in core@shell structures, Xie et al. have found that the design of NaYF4:20%Yb3+,0.5%Tm3+,1%Nd3+@NaYF4:20%Nd3+ results in upconversion emission around seven times stronger than that of NaYF4:Nd3+,Yb3+,Tm3+@NaYF461. To further reduce the cross-relaxation and back energy transfer from activators to Nd3+ sensitizers, Zhong et al. reported a nanostructure design in the form of NaYF4:Yb3+,Er3+@NaYF4:Yb3+@NaNdF4:Yb3+, in which the intermediate NaYF4:Yb3+ shell separates Er3+ activators from Nd3+ primary sensitizers74. With the doping concentration of Nd3+ being pushed to 90%, there is eight times more upconversion luminescence produced, compared to the NaYF4:Yb3+,Er3+@NaYF4:Nd3+ structure. Encouragingly, a more sophisticated doping pattern of NaYF4:2%Er3+,30%Yb3+@NaYF4:20%Yb3+@NaNdF4:10%Yb3+, with fine-tuning of Yb3+ concentrations at different layers, was found to facilitate more efficient energy transfer process of (Nd3+ → Yb3+) → (Yb3+) → (Yb3+ → Er3+) at higher Nd3+ doping concentration. This design further reduces the requirement in the excitation power, so that upconversion luminescence has been observed even under a 740 nm LED75. A similar energy migration strategy has been proposed to get cooperative emission from Tb3+ ions, which demonstrated a tenfold upconversion enhancement under 800 nm photoexcitation of Nd3+ ions as compared to Yb3+ sensitization.76 The ratiometric Nd3+ → Yb3+ and Yb3+ → Er3+ energy transfer processes in the core@shell nanocrystals have also been used for temperature sensing in two different temperature ranges77. More detailed and systematic studies of the concentrations of both the primary sensitizer and secondary sensitizers will improve the efficiency of energy cascade.

Combining strategies presented above (Figure 3a, c), upconversion tuning with high-doping concentrations can be achieved by either Gd3+-mediated energy migration or Yb3+-mediated absorption/migration. For example, the core@multishell structure of NaYbF4:50%Nd3+@NaGdF4:Yb3+,Tm3+@NaGdF4:A (A: activator Eu3+, Tb3+, or Dy3+) has been utilized to initiate the energy migration from Gd3+ to the activators with high concentration78. In this system, the Nd3+-sensitized UCNPs displayed emissions spanning from the UV to the visible region with high efficiency through a single wavelength excitation at 808 nm. More recently, Liu et al. designed a multilayer nanoparticle for simultaneously displaying short- and long-lived upconversion emission with high concentrations of different dopants at different layers, making multilevel anti-counterfeiting possible at a single-particle level79.

Blocking layer separation: In addition to the strategies of tuning excitation and emission properties, the control over doping location with a blocking layer (Figure 3e) has been demonstrated for orthogonal emissions78,80,81, spectral/lifetime multiplexing82, upconverting/downshifting83, multimode imaging84, and multi-optical functions in single particles65. For example, reversible isomerization of spiropyran derivatives has been achieved by the orthogonal emissions of core@multishell UCNPs with a high-doping concentration of Nd3+ under irradiation at 800 and 980 nm (Figure 3f)80. A similar idea was used to efficiently trigger a reversible photocyclization of the chiral diarylethene molecular switch by the UV and visible luminescence from core@multishell UCNPs with dual wavelength NIR light transduction properties85. The emission colours of these Ho3+/Tm3+ co-doped NaGdF4:Yb3+ UCNPs can be tuned by changing the laser power density or temperature, due to the different spectral responses86. By design and synthesis of NaGdF4:Nd3+@NaYF4@NaGdF4:Nd3+,Yb3+,Er3+@NaYF4 nanoparticles, both upconversion and downshifting luminescence, sensitized by highly doped Nd3+, can be achieved without cross interference83. Moreover, excited Nd3+ ions can transfer energy to other lanthanide ions and result in tunable downshifting emission. For instance, co-doping Yb3+ with Nd3+ at high concentrations would give an intense NIR emission centred around 980 nm due to the efficient energy transfer from Nd3+ to Yb3+87. The spectral and lifetime characteristics can correlate orthogonally with excitation by constructing noninterfering luminescent regions in a nanoparticle, which enables the multiplexed fingerprint and time-gated luminescent imaging in both spectral and lifetime dimensions82. More recently, Marciniak et al. have demonstrated the heterogeneous doping of Nd3+ ions with different concentrations in different parts of NaNdF4@NaYF4@NaYF4:1%Nd3+ nanoparticles to achieve three optical functions, namely efficient (η > 72%) light-to-heat conversion, bright NIR emission and relatively sensitive (SR > 0.1% K−1) localized temperature quantification65. The undoped NaYF4 intermediate shell enables the separation of the 1% Nd3+-doped outer shell (for efficient Stokes emission) from 100% Nd3+-doped core (for cross-relaxation based efficient light-to-heat conversion).

Emerging applications enabled by cross-relaxation

Cross-relaxation has often been perceived as being deleterious, but new research shows that cross-relaxation can render many unique properties, such as single-band emission88,89, energy looping73, tunable colour/lifetime63,90, enhanced downshifting emissions91 and photo-avalanche effect for amplified-stimulated emission1,92.

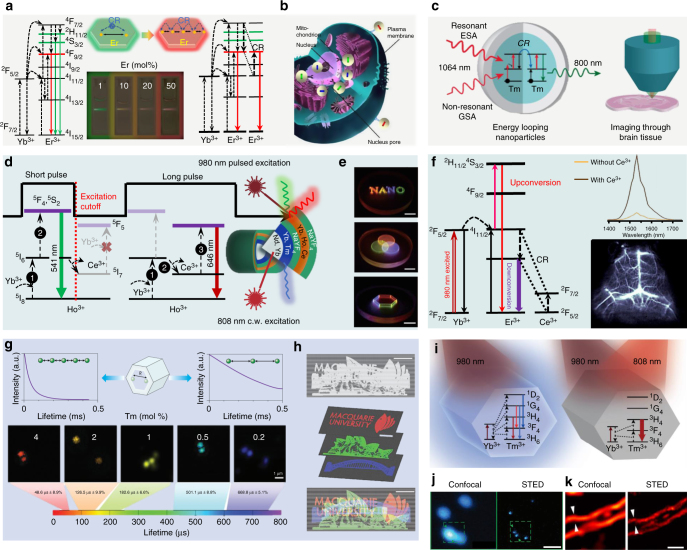

Single-band emission: High-throughput molecular profiling requires optical multiplexing of single-band emission probes to target multiple analytes without crosstalk (Figure 4b), but each lanthanide ion emitter in an UCNP has multiple energy levels with multiple emission peaks93. Cross-relaxation by high-doping concentration has been used to quench the unwanted emission bands to yield single-band emission94,95. Chan et al. used combinatorial screening of multiple doped NaYF4 nanocrystals to identify a series of doubly and triply doped nanoparticles with pure emission spectra at various visible wavelengths96. Approaching 100% red emission output has been reported by Wei et al. using highly doped activators, where the cross-relaxation effect dominates and quenches the green or blue emissions (Figure 4a)89. This strategy was successful in achieving pure red 696 or 660 nm upconversion emission as well as precisely tuning upconversion colours to study the underlying upconversion mechanisms.

Fig. 4.

Cross-relaxation-enabled nanotechnology using highly doped upconversion nanocrystals. a Upconversion mechanisms of Er3+ at low- and high-doping levels and the fluorescence photographs of NaYbF4:Er3+ UCNPs with different concentrations of the activator, the cross-relaxation effect induces pure red emission with increasing Er3+ concentration. Adapted with permission from ref. 89 Copyright (2014) American Chemical Society. b Application of single-band upconversion nanoprobes for multiplexed in situ molecular mapping of cancer biomarkers. Adapted from ref. 93. c Core@shell design and energy-looping mechanism in highly Tm3+-doped NaYF4, and their application for deep-tissue brain imaging. Reproduced with permission from ref. 73 Copyright (2016) American Chemical Society. d Design and mechanism of NaYF4-based core@shell nanocrystals capable of emitting tunable colours through the combined use of a continuous wave 808 nm laser and a 980 nm laser with short or long pulse. Adapted from ref. 63. e Its application in 3D and full-colour display systems with high-spatial resolution and locally addressable colour gamut, scale bars represent 1 cm. Adapted from ref. 63. f Simplified energy-level diagrams depicting the energy transfer between Yb3+, Er3+, and Ce3+ ions, downshifting luminescence spectra of the NaYF4:Yb3+,Er3+ UCNPs with and without Ce3+ doping and their application for cerebral vascular image through the second NIR window. Adapted from ref. 91. g Lifetime tuning scheme and time-resolved confocal images of NaYF4:Yb3+,Tm3+ UCNPs with increasing concentration of Tm3+, scale bar represents 1 μm. Adapted from refs. 90,101. h Their application in lifetime-encoded document security, scale bars represent 5 mm. Adapted from ref. 90. i Energy-level diagrams of highly Tm3+-doped UCNPs under 980 nm and/or 808 nm illumination. Adapted from ref. 1. j Confocal versus STED super-resolution images of the 40 nm 8% Tm3+-doped UCNPs, scale bar represents 500 nm. Adapted from ref. 1. k Confocal versus STED super-resolution images of cellular cytoskeleton labelled with antibody-conjugated 11.8 nm NaGdF4:18%Yb3+,10%Tm3+ nanocrystals, scale bar represents 1 μm. Adapted from ref. 92

More recently, Chen et al. presented a new class of β-NaErF4:0.5%Tm3+@NaYF4 nanocrystals with bright red upconversion luminescence through high concentration Er3+-based host sensitization, in which Tm3+ ions are employed to trap excitation energy and to minimize the luminescence quenching effect97. Introducing high concentrations of Ce3+ into NaYF4:Yb3+/Ho3+ or NaYF4:40%Gd3+ have greatly enhanced the red-to-green upconversion emission ratio of Ho3+ through effective cross-relaxation between Ce3+ and Ho3+98,99. Similarly, combining the strategy presented in Figure 3c, single-band red upconversion luminescence of Ho3+ has been achieved under 808 nm excitation from NaGdF4:Yb3+,Ho3+,Ce3+@NaYF4:Yb3+,Nd3+ core@shell nanoparticles with the shell layer highly doped with Nd3+ (around 10%)88. Also, doping a high concentration of Mn2+ into NaYF4:Yb3+,Er3+ nanocrystals has resulted in pure single-band red upconversion emission via an efficient energy transfer between Mn2+ and Er3+ 95. Levy et al. used an energy-looping mechanism to non-resonantly excite upconversion in highly Tm3+-doped NaYF4:Tm3+ nanoparticles with 1064 nm light for deep-tissue imaging73. In this work, as illustrated in Figure 4c, one Tm3+ ion can cross-relax by donating energy partially to a second Tm3+ ion in its ground state, resulting in two Tm3+ ions in their intermediate 3F4 state to enable efficient excited-state absorption at 1064 nm and emit 800 nm emissions73.

Full-colour/lifetime tuning: The energy transfer between the dopant ions in a core@shell nanostructure has also been found to be controllable by adjusting the pulse duration of the excitation laser (Figure 4d, e)63. By increasing the pulse duration from 0.2 to 6 ms (at 980 nm), the intensity ratio of green-to-red emission from the shell of NaYF4:Yb3+,Ho3+,Ce3+ with a high concentration of Ce3+ can be continuously modulated. The energy transfer from Ho3+ to Ce3+ by a cross-relaxation process 5I6(Ho3+) + 2F5/2(Ce3+) → 5I7(Ho3+) + 2F7/2(Ce3+) is only allowed under a long pulse excitation, while the transition from 5I6(Ho3+) to higher levels of 5F4, 5S2 prevails over the above cross-relaxation process involving Ce3+ by a short-pulse excitation. This judicious design has further generated pure blue upconversion emission by pumping at 800 nm by Nd3+ → Yb3+ → Tm3+ with a high concentration of Nd3+63. Cross-relaxation has been employed for enhancing the downshifting emission between 1500 and 1700 nm for high-spatial resolution and deep-tissue penetration of photons for cerebral vascular image in the second NIR window91. Facilitated by the high Ce3+-doping concentration, the Er3+ 4I13/2 level is significantly populated through the accelerated non-radiative relaxation of Er3+ 4I11/2 → 4I13/2 (Figure 4f), resulting in a ninefold enhancement of the downshifting 1550 nm luminescence of NaYbF4:2%Er3+,2%Ce3+@NaYF4 nanoparticles.

Apart from colour tuning, luminescence decay lifetimes form another set of optical signatures79,82,90,100. Manipulating the degree of cross-relaxation by different Tm3+-doping concentrations can create a large range of lifetimes from 25.6 to 662.4 μs in the blue emission band, forming a library of lifetime-tunable τ-dots for optical multiplexing (Figure 4g)90,101. Such an optical signature can be used as barcoding for security applications, and only a properly designed time-resolved detector can decode such a set of diverse time-domain optical barcodes. As demonstrated in Figure 4h, the ability to resolve superimposed lifetime-encoded images suggests a new way of optical data storage with high densities and fast data readout rates.

Super-resolution imaging: Another intriguing example is nanoscopic imaging using highly Tm3+-doped UCNP as an effective stimulated emission depletion (STED) probe. The advent of super-resolution microscopy, such as STED fluorescence microscopy, has revolutionized biological fluorescence microscopy102,103, but STED requires extremely high-power laser densities and specialized fluorescent labels to achieve super-resolution imaging. Using the cross-relaxation effect, Liu et al. discovered a photon avalanche effect that facilitates the establishment of population inversion within a single highly Tm3+-doped UCNP (Figure 4i)1. This enables sub-30 nm optical super-resolution imaging with a STED beam density two orders of magnitude lower than that used on fluorescent dyes (Figure 4j)1. This effect has only been found in highly doped UCNPs because the cross-relaxation process, dominated at a high Tm3+-doping concentration, can trigger a photon avalanche to establish a population inversion between metastable and ground levels. In that respect, upon 808 nm beam depletion amplified-stimulated emission is realized, resulting in a higher-depletion efficiency and thus a reduced saturation intensity. Using this new mode of upconversion nanoscopy, Zhan et al. have reported super-resolution imaging of cell cytoskeleton with 11.8 nm NaGdF4:18%Yb3+,10%Tm3+ UCNPs (Figure 4k)92. Other schemes, based on Pr3+ or Er3+ doped UCNPs, have also been explored for super-resolution nanoscopic applications104,105

Perspective

One of the major challenges to transform upconversion nanotechnology into real-world applications is to enhance the brightness and emission efficiency of UCNPs4. This review summarizes the advances in the development of highly doped UCNPs and emerging applications by overcoming the concentration quenching effect or smart exploitation of unique features of highly doped nanomaterials. Notably, the unique optical properties arising from the range of layer-by-layer heterogeneously doped nanoparticles have attracted immense scientific and technological interests. The intentional doping of high concentration of lanthanide ions into different sections across a single UCNP has been explored to enhance the desirable optical properties as well as introducing multifunctionality. Thus far, only spherical core@shell structures have been studied to modulate the energy transfer, while further investigations of heterogeneous one-dimension structures, such as rods, plates and dumbbells, are still needed60,106,107. Controlled growth toward atomic precision is highly sought after for gaining a full understanding of the sophisticated energy transfer processes and for fine-tuning upconversion luminescence. For example, arranging high concentrations of dopants into a host nanocrystal along one direction could confine the direction of energy transfer, which may create new properties and enable novel applications going beyond the current isotropic 3D transfer processes.

The unique optical properties of highly doped UCNPs discussed above have largely impacted biological and biomedical fields, such as single-molecule sensing18, high-throughput multiplexed detection79,82,90 and super-resolution nanoscopy1,92. It is noteworthy that small-sized and bright UCNPs are indispensable to those applications. Owing to brightness issues, the majority of currently developed UCNPs are relatively large (around 20–50 nm). It has been challenging to design and fabricate highly doped sub-10 nm UCNPs with emission output comparable with that of quantum dots and organic dyes. To our delight, fine-tuning of the particle size below 10 nm was recently demonstrated for UCNP systems by homogeneous doping108 or at a high-doping concentrations109. Nonetheless, the fabrication of sub-10 nm UCNPs with heterogeneously doped core@shell structures remains a formidable challenge.

The surface molecules not only play an essential role in the controlled synthesis of nanomaterials, but they can also significantly alter the nanomaterial’s luminescence properties with new effects110,111. Examples include the recent developments of dye-sensitized UCNPs16,62,112,113 and surface phonon enhanced UCNPs in a thermal field111. Normally, lanthanide-doped inorganic nanocrystals exhibit narrowband (FWHM around 20 nm) and low (10−20 cm−2) absorption coefficients. It is notable that organic dyes have more than 10 times broader absorption spectra and 103–104-fold higher absorption cross-sections than Yb3+ sensitizer ions commonly used in UCNPs16,62,112,113. Therefore, despite photostability issues, the organic–inorganic hybrid nanomaterials (for example, dye-sensitized upconversion nanosystems) offer various possibilities16. Utilizing the efficient energy transfer of cyanine derivatives anchored on the surface of NaYbF4:Tm3+@NaYF4:Nd3+ nanoparticles, Chen et al. demonstrated dye-sensitized upconversion16. Upon 800 nm excitation, a sequential energy transfer, dye → Nd3+ → Yb3+ → activators, has enabled the dye-sensitized nanoparticles to emit around 25 times stronger than canonical NaYF4:Yb3+,Tm3+@NaYF4 nanoparticles excited at 980 nm. Similarly, the common triplet energy transfer could occur between inorganic nanocrystals and the surface dyes114–118. While thermal quenching broadly limits the luminescence efficiency at high temperatures in optical materials, Zhou et al. report that the phonons at the surface of highly Yb3+-doped UCNPs could combat thermal quenching and significantly enhance the upconversion brightness, particularly for sub-10 nm nanocrystals111. We believe that these hybrid and heterogeneously doped nanomaterials have the potential in pushing the performance of UCNPs to a new level and imparting multifaceted photonic applications.

Acknowledgements

This project is primarily supported by the Australian Research Council (ARC) Future Fellowship Scheme (D.J., FT130100517), ARC Discovery Early Career Researcher Award Scheme (J.Z., DE180100669), National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, 61729501, 51720105015), Singapore Ministry of Education (Grant R143000627112 and R143000642112), National Research Foundation, Prime Minister’s Office, Singapore under its Competitive Research Program (CRP Award No. NRF-CRP15-2015-03), and the European Upconversion Network (COST Action CM1403).

Author contributions

S.W. and D.J. were responsible for structuring and drafting the manuscript; J.Z. developed the boxes; S.W., J.Z., and K.Z. developed the figures; and S.W., J.Z., K.Z., A.B., X.L., and D.J. edited and revised the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Artur Bednarkiewicz, Email: a.bednarkiewicz@int.pan.wroc.pl.

Xiaogang Liu, Email: chmlx@nus.edu.sg.

Dayong Jin, Email: dayong.jin@uts.edu.au.

References

- 1.Liu Y, et al. Amplified stimulated emission in upconversion nanoparticles for super-resolution nanoscopy. Nature. 2017;543:229–233. doi: 10.1038/nature21366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou B, Shi B, Jin D, Liu X. Controlling upconversion nanocrystals for emerging applications. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2015;10:924–936. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2015.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang F, et al. Simultaneous phase and size control of upconversion nanocrystals through lanthanide doping. Nature. 2010;463:1061–1065. doi: 10.1038/nature08777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilhelm S. Perspectives for upconverting nanoparticles. ACS Nano. 2017;11:10644–10653. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b07120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan EM. Combinatorial approaches for developing upconverting nanomaterials: high-throughput screening, modeling, and applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015;44:1653–1679. doi: 10.1039/C4CS00205A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu X, Yan CH, Capobianco JA. Photon upconversion nanomaterials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015;44:1299–1301. doi: 10.1039/C5CS90009C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tu L, Liu X, Wu F, Zhang H. Excitation energy migration dynamics in upconversion nanomaterials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015;44:1331–1345. doi: 10.1039/C4CS00168K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen X, Peng D, Ju Q, Wang F. Photon upconversion in core-shell nanoparticles. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015;44:1318–1330. doi: 10.1039/C4CS00151F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang P, Deng P, Yin Z. Concentration quenching in Yb:YAG. J. Lumin. 2002;97:51–54. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2313(01)00426-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Viger ML, Live LS, Therrien OD, Boudreau D. Reduction of self-quenching in fluorescent silica-coated silver nanoparticles. Plasmonics. 2008;3:33–40. doi: 10.1007/s11468-007-9051-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tavernaro I, Cavelius C, Peuschel H, Kraegeloh A. Bright fluorescent silica-nanoparticle probes for high-resolution STED and confocal microscopy. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2017;8:1283–1296. doi: 10.3762/bjnano.8.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Danielmeyer HG, Blätte M, Balmer P. Fluorescence quenching in Nd:YAG. Appl. Phys. 1973;1:269–274. doi: 10.1007/BF00889774. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haase M, Schäfer H. Upconverting nanoparticles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:5808–5829. doi: 10.1002/anie.201005159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boyer JC, van Veggel FCJM. Absolute quantum yield measurements of colloidal NaYF4: Er3+, Yb3+ upconverting nanoparticles. Nanoscale. 2010;2:1417–1419. doi: 10.1039/c0nr00253d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang F, Wang J, Liu X. Direct evidence of a surface quenching effect on size-dependent luminescence of upconversion nanoparticles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:7456–7460. doi: 10.1002/anie.201003959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen G, et al. Energy-cascaded upconversion in an organic dye-sensitized core/shell fluoride nanocrystal. Nano Lett. 2015;15:7400–7407. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b02830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao J, et al. Single-nanocrystal sensitivity achieved by enhanced upconversion luminescence. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013;8:729–734. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2013.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gargas DJ, et al. Engineering bright sub-10-nm upconverting nanocrystals for single-molecule imaging. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2014;9:300–305. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2014.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dexter DL, Schulman JH. Theory of concentration quenching in inorganic phosphors. J. Chem. Phys. 1954;22:1063–1070. doi: 10.1063/1.1740265. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen RF, Knutson JR. Mechanism of fluorescence concentration quenching of carboxyfluorescein in liposomes: energy transfer to nonfluorescent dimers. Anal. Biochem. 1988;172:61–77. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(88)90412-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arbeloa IL. Dimeric and trimeric states of the fluorescein dianion. Part 2.-Effects on fluorescence characteristics. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 1981;2:1735–1742. doi: 10.1039/F29817701735. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao GJ, Liu JY, Zhou LC, Han KL. Site-selective photoinduced electron transfer from alcoholic solvents to the chromophore facilitated by hydrogen bonding: a new fluorescence quenching mechanism. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:8940–8945. doi: 10.1021/jp0734530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Imhof A, et al. Spectroscopy of fluorescein (FITC) dyed colloidal silica spheres. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1999;103:1408–1415. doi: 10.1021/jp983241q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang J, et al. Enhancing multiphoton upconversion through energy clustering at sublattice level. Nat. Mater. 2014;13:157–162. doi: 10.1038/nmat3804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson NJJ, et al. Direct evidence for coupled surface and concentration quenching dynamics in lanthanide-doped nanocrystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:3275–3282. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b00223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jares-Erijman EA, Jovin TM. FRET imaging. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21:1387–1395. doi: 10.1038/nbt896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun T, Ma R, Qiao X, Fan X, Wang F. Shielding upconversion by surface coating: a study of the emission enhancement factor. Chemphyschem. 2016;17:766–770. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201500724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang F, Liu X. Upconversion multicolor fine-tuning: visible to near-infrared emission from lanthanide-doped NaYF4 nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:5642–5643. doi: 10.1021/ja800868a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heer S, Kömpe K, Güdel HU, Haase M. Highly efficient multicolour upconversion emission in transparent colloids of lanthanide-doped NaYF4 nanocrystals. Adv. Mater. 2004;16:2102–2105. doi: 10.1002/adma.200400772. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kawamura Y, Brooks J, Brown JJ, Sasabe H, Adachi C. Intermolecular interaction and a concentration-quenching mechanism of phosphorescent Ir(III) complexes in a solid film. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006;96:017404. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.017404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nadort A, Zhao J, Goldys EM. Lanthanide upconversion luminescence at the nanoscale: fundamentals and optical properties. Nanoscale. 2016;8:13099–13130. doi: 10.1039/C5NR08477F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Auzel F. Upconversion and anti-stokes processes with f and d ions in solids. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:139–174. doi: 10.1021/cr020357g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qin X, Liu X, Huang W, Bettinelli M, Liu X. Lanthanide-activated phosphors based on 4f-5d optical transitions: theoretical and experimental aspects. Chem. Rev. 2017;117:4488–4527. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang F, et al. Tuning upconversion through energy migration in core–shell nanoparticles. Nat. Mater. 2011;10:968–973. doi: 10.1038/nmat3149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang YF, et al. Nd3+-sensitized upconversion nanophosphors: efficient in vivo bioimaging probes with minimized heating effect. ACS Nano. 2013;7:7200–7206. doi: 10.1021/nn402601d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zuo J, et al. Employing shells to eliminate concentration quenching in photonic upconversion nanostructure. Nanoscale. 2017;9:7941–7946. doi: 10.1039/C7NR01403A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Benz F, Strunk HP. Rare earth luminescence: a way to overcome concentration quenching. AIP Adv. 2012;2:042115. doi: 10.1063/1.4760248. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marciniak L, Strek W, Bednarkiewicz A, Lukowiak A, Hreniak D. Bright upconversion emission of Nd3+ in LiLa1−xNdxP4O12 nanocrystalline powders. Opt. Mater. 2011;33:1492–1494. doi: 10.1016/j.optmat.2011.03.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu X, et al. Depth-profiling of Yb3+sensitizer ions in NaYF4 upconversion nanoparticles. Nanoscale. 2017;9:7719–7726. doi: 10.1039/C7NR01456B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pilch A, et al. Shaping luminescent properties of Yb3+ and Ho3+Co-doped upconverting core–shell β-NaYF4 nanoparticles by dopant distribution and spacing. Small. 2017;13:1701635. doi: 10.1002/smll.201701635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu X, et al. Breakthrough in concentration quenching threshold of upconversion luminescence via spatial separation of the emitter doping area for bio-applications. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:11957–11959. doi: 10.1039/c1cc14774a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jin, D. & Zhao, J. Enhancing upconversion luminescence in rare-earth doped particles. US patent US20150252259A1 (2015).

- 43.Li X, Wang R, Zhang F, Zhao D. Engineering homogeneous doping in single nanoparticle to enhance upconversion efficiency. Nano Lett. 2014;14:3634–3639. doi: 10.1021/nl501366x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang F, et al. Microscopic inspection and tracking of single upconversion nanoparticles in living cells. Light Sci. Appl. 2018;7:e18007. doi: 10.1038/lsa.2018.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wei W, et al. Alleviating luminescence concentration quenching in upconversion nanoparticles through organic dye sensitization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:15130–15133. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b09474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen G, Ohulchanskyy TY, Kumar R, Ågren H, Prasad PN. Ultrasmall monodisperse NaYF4:Yb3+/Tm3+nanocrystals with enhanced near-infrared to near-infrared upconversion photoluminescence. ACS Nano. 2010;4:3163–3168. doi: 10.1021/nn100457j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shen B, et al. Revisiting the optimized doping ratio in core/shell nanostructured upconversion particles. Nanoscale. 2017;9:1964–1971. doi: 10.1039/C6NR07687D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen G, et al. (α-NaYbF4:Tm3+)/CaF2 core/shell nanoparticles with efficient near-infrared to near-infrared upconversion for high-contrast deep tissue bioimaging. ACS Nano. 2012;6:8280–8287. doi: 10.1021/nn302972r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Punjabi A, et al. Amplifying the red-emission of upconverting nanoparticles for biocompatible clinically used prodrug-induced photodynamic therapy. ACS Nano. 2014;8:10621–10630. doi: 10.1021/nn505051d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shen J, et al. Tunable near infrared to ultraviolet upconversion luminescence enhancement in (α-NaYF4:Yb,Tm)/CaF2 core/shell nanoparticles for in situ real-time recorded biocompatible photoactivation. Small. 2013;9:3213–3217. doi: 10.1002/smll.201370117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xue M, et al. Highly enhanced cooperative upconversion luminescence through energy transfer optimization and quenching protection. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2016;8:17894–17901. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b05609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ma C, et al. Optimal sensitizer concentration in single upconversion nanocrystals. Nano Lett. 2017;17:2858–2864. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b05331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang Y, Liu X. Nanocrystals: shining a light on upconversion. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013;8:702–703. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2013.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li Y, et al. Enhancing upconversion fluorescence with a natural bio-microlens. ACS Nano. 2017;11:10672–10680. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b04420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang L, et al. Reversible near-infrared light directed reflection in a self-organized helical superstructure loaded with upconversion nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:4480–4483. doi: 10.1021/ja500933h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen X, et al. Confining energy migration in upconversion nanoparticles towards deep ultraviolet lasing. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:10304. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Drees C, et al. Engineered upconversion nanoparticles for resolving protein interactions inside living cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:11668–11672. doi: 10.1002/anie.201603028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pliss A, et al. Subcellular optogenetics enacted by targeted nanotransformers of near-infrared light. ACS Photonics. 2017;4:806–814. doi: 10.1021/acsphotonics.6b00475. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kovalenko MV, et al. Prospects of nanoscience with nanocrystals. ACS Nano. 2015;9:1012–1057. doi: 10.1021/nn506223h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu D, et al. Three-dimensional controlled growth of monodisperse sub-50 nm heterogeneous nanocrystals. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:10254. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xie X, et al. Mechanistic investigation of photon upconversion in Nd3+-sensitized core–shell nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:12608–12611. doi: 10.1021/ja4075002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen G, et al. Efficient broadband upconversion of near-infrared light in dye-sensitized core/shell nanocrystals. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2016;4:1760–1766. doi: 10.1002/adom.201600556. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Deng R, et al. Temporal full-colour tuning through non-steady-state upconversion. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2015;10:237–242. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2014.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hao S, et al. Nd3+-sensitized multicolor upconversion luminescence from a sandwiched core/shell/shell nanostructure. Nanoscale. 2017;9:10633–10638. doi: 10.1039/C7NR02594G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Marciniak L, Pilch A, Arabasz S, Jin D, Bednarkiewicz A. Heterogeneously Nd3+doped single nanoparticles for NIR-induced heat conversion, luminescence, and thermometry. Nanoscale. 2017;9:8288–8297. doi: 10.1039/C7NR02630G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen X, et al. Energy migration upconversion in Ce(III)-doped heterogeneous core−shell−shell nanoparticles. Small. 2017;13:1701479. doi: 10.1002/smll.201701479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang C, et al. White-light emission from an integrated upconversion nanostructure: toward multicolor displays modulated by laser power. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:11531–11535. doi: 10.1002/anie.201504518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Deng R, Wang J, Chen R, Huang W, Liu X. Enabling Förster resonance energy transfer from large nanocrystals through energy migration. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:15972–15979. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b09349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li X, et al. Energy migration upconversion in manganese(II)-doped nanoparticles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:13312–13317. doi: 10.1002/anie.201507176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhou B, Yang W, Han S, Sun Q, Liu X. Photon upconversion through Tb3+-mediated interfacial energy transfer. Adv. Mater. 2015;27:6208–6212. doi: 10.1002/adma.201503482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nam SH, et al. Long-term real-time tracking of lanthanide ion doped upconverting nanoparticles in living cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:6093–6097. doi: 10.1002/anie.201007979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Xie X, et al. Emerging ≈800nm excited lanthanide-doped upconversion nanoparticles. Small. 2017;13:1602843. doi: 10.1002/smll.201602843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Levy ES, et al. Energy-looping nanoparticles: harnessing excited-state absorption for deep-tissue imaging. ACS Nano. 2016;10:8423–8433. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.6b03288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhong Y, et al. Elimination of photon quenching by a transition layer to fabricate a quenching-shield sandwich structure for 800nm excited upconversion luminescence of Nd3+-sensitized nanoparticles. Adv. Mater. 2014;26:2831–2837. doi: 10.1002/adma.201304903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhong Y, Rostami I, Wang Z, Dai H, Hu Z. Energy migration engineering of bright rare-earth upconversion nanoparticles for excitation by light-emitting diodes. Adv. Mater. 2015;27:6418–6422. doi: 10.1002/adma.201502272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Prorok K, Pawlyta M, Stręk W, Bednarkiewicz A. Energy migration up-conversion of Tb3+ in Yb3+ and Nd3+ codoped active-core/active-shell colloidal nanoparticles. Chem. Mater. 2016;28:2295–2300. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.6b00353. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Marciniak L, Prorok K, Frances-Soriano L, Perez-Prieto J, Bednarkiewicz A. A broadening temperature sensitivity range with a core-shell YbEr@YbNd double ratiometric optical nanothermometer. Nanoscale. 2016;8:5037–5042. doi: 10.1039/C5NR08223D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wen H, et al. Upconverting near-infrared light through energy management in core–shell–shell nanoparticles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:13419–13423. doi: 10.1002/anie.201306811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Liu X, et al. Binary temporal upconversion codes of Mn2+-activated nanoparticles for multilevel anti-counterfeiting. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:899. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00916-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lai J, Zhang Y, Pasquale N, Lee KB. An upconversion nanoparticle with orthogonal emissions using dual nir excitations for controlled two-way photoswitching. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:14419–14423. doi: 10.1002/anie.201408219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Li X, et al. Filtration shell mediated power density independent orthogonal excitations–emissions upconversion luminescence. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:2464–2469. doi: 10.1002/anie.201510609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dong H, et al. Versatile spectral and lifetime multiplexing nanoplatform with excitation orthogonalized upconversion luminescence. ACS Nano. 2017;11:3289–3297. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b00559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Li X, et al. Nd3+ sensitized up/down converting dual-mode nanomaterials for efficient in-vitro and in-vivo bioimaging excited at 800nm. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:3536. doi: 10.1038/srep03536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.He S, et al. Simultaneous enhancement of photoluminescence, MRI relaxivity, and CT contrast by tuning the interfacial layer of lanthanide heteroepitaxial nanoparticles. Nano Lett. 2017;17:4873–4880. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b01753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wang L, et al. Luminescence-driven reversible handedness inversion of self-organized helical superstructures enabled by a novel near-infrared light nanotransducer. Adv. Mater. 2015;27:2065–2069. doi: 10.1002/adma.201405690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shao Q, et al. Emission color tuning of core/shell upconversion nanoparticles through modulation of laser power or temperature. Nanoscale. 2017;9:12132–12141. doi: 10.1039/C7NR03682E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Li Y, et al. A versatile imaging and therapeutic platform based on dual-band luminescent lanthanide nanoparticles toward tumor metastasis inhibition. ACS Nano. 2016;10:2766–2773. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b07873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chen D, et al. Nd3+-sensitized Ho3+single-band red upconversion luminescence in core–shell nanoarchitecture. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2015;6:2833–2840. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.5b01180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wei W, et al. Cross relaxation induced pure red upconversion in activator- and sensitizer-rich lanthanide nanoparticles. Chem. Mater. 2014;26:5183–5186. doi: 10.1021/cm5022382. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lu Y, et al. Tunable lifetime multiplexing using luminescent nanocrystals. Nat. Photon. 2014;8:32–36. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2013.322. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zhong Y, et al. Boosting the downshifting luminescence of rare-earth nanocrystals for biological imaging beyond 1500nm. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:737. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00917-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhan Q, et al. Achieving high-efficiency emission depletion nanoscopy by employing cross relaxation in upconversion nanoparticles. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:1058. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01141-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zhou L, et al. Single-band upconversion nanoprobes for multiplexed simultaneous in situ molecular mapping of cancer biomarkers. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:6938. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wang J, Wang F, Wang C, Liu Z, Liu X. Single-band upconversion emission in lanthanide-doped KMnF3 nanocrystals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:10369–10372. doi: 10.1002/anie.201104192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tian G, et al. Mn2+dopant-controlled synthesis of NaYF4:Yb/Er upconversion nanoparticles for in vivo imaging and drug delivery. Adv. Mater. 2012;24:1226–1231. doi: 10.1002/adma.201104741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chan EM, et al. Combinatorial discovery of lanthanide-doped nanocrystals with spectrally pure upconverted emission. Nano Lett. 2012;12:3839–3845. doi: 10.1021/nl3017994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chen Q, et al. Confining excitation energy in Er3+-sensitized upconversion nanocrystals through Tm3+-mediated transient energy trapping. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:7605–7609. doi: 10.1002/anie.201703012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chen G, Liu H, Somesfalean G, Liang H, Zhang Z. Upconversion emission tuning from green to red in Yb 3+/Ho 3+-codoped NaYF 4 nanocrystals by tridoping with Ce 3+ions. Nanotechnology. 2009;20:385704. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/20/38/385704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Gao W, et al. Enhanced red upconversion luminescence by codoping Ce3+in [small beta]-NaY(Gd0.4)F4:Yb3+/Ho3+nanocrystals. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2014;2:5327–5334. doi: 10.1039/C4TC00585F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zhao J, et al. Upconversion luminescence with tunable lifetime in NaYF4:Yb,Er nanocrystals: role of nanocrystal size. Nanoscale. 2013;5:944–952. doi: 10.1039/C2NR32482B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Deng R, Liu X. Optical multiplexing: tunable lifetime nanocrystals. Nat. Photon. 2013;8:10–12. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2013.353. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Balzarotti F, et al. Nanometer resolution imaging and tracking of fluorescent molecules with minimal photon fluxes. Science. 2016;355:606–612. doi: 10.1126/science.aak9913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hanne J, et al. STED nanoscopy with fluorescent quantum dots. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7127. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Shin K, et al. Distinct mechanisms for the upconversion of NaYF4:Yb3+, Er3+nanoparticles revealed by stimulated emission depletion. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017;19:9739–9744. doi: 10.1039/C7CP00918F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kolesov R, et al. Super-resolution upconversion microscopy of praseodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet nanoparticles. Phys. Rev. B. 2011;84:153413. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.84.153413. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Zhuo, Z. et al. Manipulating energy transfer in lanthanide-doped single nanoparticles for highly enhanced upconverting luminescence. Chem. Sci.8, 5050–5056 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 107.Wen HQ, et al. Sequential growth of NaYF4:Yb/Er@NaGdF4 nanodumbbells for dual-modality fluorescence and magnetic resonance imaging. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2017;9:9226–9232. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b16842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Rinkel T, Raj AN, Dühnen S, Haase M. Synthesis of 10nm β-NaYF4:Yb,Er/NaYF4 core/shell upconversion nanocrystals with 5nm particle cores. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:1164–1167. doi: 10.1002/anie.201508838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Shi, R. et al. Tuning hexagonal NaYbF4 nanocrystals down to sub-10 nm for enhanced photon upconversion. Nanoscale 9, 13739–13746 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 110.Boles MA, Ling D, Hyeon T, Talapin DV. The surface science of nanocrystals. Nat. Mater. 2016;15:141–153. doi: 10.1038/nmat4526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Zhou J, et al. Activation of the surface dark-layer to enhance upconversion in a thermal field. Nat. Photon. 2018;12:154–158. doi: 10.1038/s41566-018-0108-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wu X, et al. Tailoring dye-sensitized upconversion nanoparticle excitation bands towards excitation wavelength selective imaging. Nanoscale. 2015;7:18424–18428. doi: 10.1039/C5NR05437K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wu X, et al. Dye-sensitized core/active shell upconversion nanoparticles for optogenetics and bioimaging applications. ACS Nano. 2016;10:1060–1066. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b06383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Mongin C, Garakyaraghi S, Razgoniaeva N, Zamkov M, Castellano FN. Direct observation of triplet energy transfer from semiconductor nanocrystals. Science. 2016;351:369–372. doi: 10.1126/science.aad6378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wu M, et al. Solid-state infrared-to-visible upconversion sensitized by colloidal nanocrystals. Nat. Photon. 2016;10:31–34. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2015.226. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Tabachnyk M, et al. Resonant energy transfer of triplet excitons from pentacene to PbSe nanocrystals. Nat. Mater. 2014;13:1033–1038. doi: 10.1038/nmat4093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Huang Z, et al. Hybrid molecule–nanocrystal photon upconversion across the visible and near-infrared. Nano Lett. 2015;15:5552–5557. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b02130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Garfield, D. J. et al. Enrichment of molecular antenna triplets amplifies upconverting nanoparticle emission. Nat. Photon. 10.1038/s41566-018-0156-x (2018).