Abstract

The objective of this study was to investigate the clinicopathological characteristics and survival outcomes of Paget disease (PD), Paget disease concomitant infiltrating duct carcinoma (PD‐IDC), and Paget disease concomitant intraductal carcinoma (PD‐DCIS). We identified 501,631 female patients from 2000 to 2013 in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database. These identified patients included patients with PD (n = 469), patients with PD‐IDC (n = 1832), and patients with PD‐DCIS (n = 1130) and infiltrating ductal carcinoma (IDC) (n = 498,076). Then, we compared the clinical characteristics of these patients with those who were diagnosed with IDC during the same period. The outcomes of these subtypes of breast carcinoma were different. Based on the overall survival, the patients with PD‐IDC had the worst prognosis (5‐year survival rate = 84.1%). The PD‐DCIS had the best prognosis (5‐year survival rate = 97.5%). Besides, among patients with Paget disease, the one who was married had a better prognosis than who were not. And, according to our research, the marital status was associated with the hormone receptor status in patients with PD‐IDC. Among three subtypes of Paget disease, patients with PD‐IDC had the worst prognosis. Besides, patients who were unmarried had worse outcomes. And the marital status of patients with PD‐IDC is associated with hormone status. The observation underscores the importance of individualized treatment.

Keywords: Infiltrating ductal carcinoma; Paget disease; surveillance, epidemiology, and end results

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women across the world. According to the WHO experts in the world each year, there are revealed from 800,000 up to 1 million new cases of breast cancer 1. Paget disease is a rare form of breast cancer that occurs in the mouth of the excretory ducts of the nipple. This rare abnormality occurs in 0.5–5% of all cases of breast cancer 2. PD is characterized by an ulcerated, ulcerated, crusted, or scaling lesion on the nipple that can extend to the areola 3. Paget's disease of the nipple is characterized by histopathological infiltration of neoplastic cells with glandular features in the epidermal layer of the nipple–areolar complex. The pathologic mechanism of PD is still unclear. However, there are two kinds of explanation of the pathologic origin of the Paget disease epidermotropic and transformation theory 4, 5. The former one considered that the cells came from the underlying ductal tumor and then move along the lactiferous ducts to the nipple. And the other theory suggested that the cells were in situ in the major lactiferous sinuses.

Characterized by malignant crusting or ulceration of the nipple, Paget disease can present in one of three ways. The first one is in conjunction with an underlying invasive cancer. The second one is in conjunction with underlying ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). The last one is alone without any underlying invasive breast carcinoma or DCIS 6. The Paget disease can be treated by central lumpectomy with breast conservation. However, the prognosis of the PD is not well. IDC is the most common breast carcinoma subtype during the world. Recent study has suggested that patients with Paget disease conjunction with invasive cancer had worse prognosis 7. Nevertheless, study about all these three kinds of PD is not being researched. And study on relationship between PD and the IDC is rare. Previous study described that Paget disease alone without an underlying cancer is rare, and it presents utmost 8% of patients with Paget disease 8.

Married persons enjoy overall better health and increase life expectancy compared the unmarried (divorced, separated, and never married) 9, 10. Previous studies have indicated a survival advantage for married persons living with cancer 11, 12, 13. And a research found that married men and women with cancer to have a 15% reduced risk of death 14. We compared with unmarried men and women in different subtypes of Paget disease. Besides the different outcomes in unmarried patients, we found the correlation between the marital status and the hormone status and the human epidermal growth factor receptor II, which can guide the individualized treatment in clinic.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

We obtained permission to access the SEER research data. The data downloaded from the SEER do not require informed patient consent. Besides, our research was approved by the Ethical Committee and Institutional Review of Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center (FDUSCC). The methods were performed in accordance with the approved guidelines.

Data source

We examined the data from the National Cancer Institute's Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program, which contains the population‐based central cancer registries of 18 geographically defined regions. For this study, we use the November 2014–18 submission.

Patient selection

We use the histopathology codes from the International Classification of Disease for Oncology third edition (ICD‐O‐3) to select female patients. In the ICD‐O‐3, the codes are defined as follows: code 8500 (ductal carcinoma), code 8540 (mammary Paget disease), code 8541 (Paget disease with infiltrating ductal carcinoma), and code 8543 (Paget disease with intraductal carcinoma). According to the ICD‐O‐3, we defined and choose the patients who had the PD (ICD‐O‐3 code 8540/3), PD‐IDC (ICD‐O‐3 code 85413), PD‐DCIS (ICD‐O‐3 code 8543/3), and IDC (ICD‐O‐3 code 8500/3). In this study, women who were diagnosed as all three kinds of PD and ICD between 2000 and 2013 were included (n = 501,631). And these identified patients included patients with PD (n = 469), patients with PD‐IDC (n = 1832), and patients with PD‐DCIS (n = 1130) and infiltrating ductal carcinoma (IDC) (n = 498,076).

Statistical analysis

Overall survival (OS) was measured from the date on which the first‐time definite diagnosis was made until the date of death, the date last known to be alive, or September 2013. Disease‐specific survival (DSS) was measured from the date of diagnosis to the date of death which is associated with breast carcinoma. The National Cancer Institute's SEER*Stat software package (version 6.1.4; built on April 13, 2005) was used to calculate incidence rates. Baseline patient demographic characteristics and tumor information were compared using the Pearson's chi‐square test for categorical variables. Survival curves were plotted according to the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the log‐rank test in a univariate analysis. Cox regression analysis was performed to compute hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) and to evaluate the effects of confounding factors. All the tests were two sided, and P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All the statistical analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software, version 22.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY).

Results

Clinicopathological characteristics of PD

Overall 447,401 patients who were diagnosed with breast carcinoma were evaluated. We evaluated 447,401 patients with breast cancer. Among these patients, 443,970 were with infiltrating ductal breast carcinoma, 469 were with mammary Paget disease, 1832 were with Paget disease with infiltrating ductal carcinoma, and 1130 were with Paget disease with intraductal carcinoma. The demographics and clinicopathological characteristics of PD, PD‐IDC, and PD‐DCIS were compared with IDC. And the results are summarized in Table 1. Using the Pearson's chi‐square test, for PD and IDC, the significant variables were age (P < 0.001), marital status (P < 0.001), laterality (P < 0.001), tumor size (P < 0.001), lymph node status (P < 0.001), Grade (P < 0.001), AJCC stage (P < 0.001), ER (estrogen receptor) status (P < 0.001), PR (progesterone receptor) status (P < 0.001), HER2 (human epidermal growth factor receptor 2) status (P < 0.001), and whether had radiation treatment (P < 0.001). For PD‐IDC and IDC, the significant characteristics were race (P = 0.011), marital status (P < 0.001), tumor size (P < 0.001), lymph node status (P < 0.001), Grade (P < 0.001), AJCC stage (P < 0.001), ER status (P < 0.001), PR status (P < 0.001), HER2 status (P < 0.001), and whether had radiation treatment (P < 0.001). For PD‐DCIS and IDC, the considerable characteristics were age (P < 0.001), marital status (P < 0.001), tumor size (P < 0.001), Grade (P < 0.001), AJCC stage (P < 0.001), ER status (P < 0.001), PR status (P < 0.001), HER2 status (P < 0.001), and whether had radiation treatment (P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with Paget disease and infiltrating duct carcinoma

| Clinical characteristics | PDN | IDCN | P‐value | PD‐IDCN | IDCN | P‐value | PD‐DCISN | IDCN | P‐value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 18–49 | 114 | 158,076 | <0.001 | 665 | 158,076 | 0.536 | 292 | 159,076 | <0.001 |

| 50–79 | 355 | 285,894 | 1167 | 285,894 | 838 | 285,894 | ||||

| Race | White | 393 | 360,769 | 0.111 | 1446 | 360,769 | 0.011 | 948 | 360,769 | 0.069 |

| Black | 45 | 41,277 | 206 | 41,277 | 87 | 41,277 | ||||

| Other | 31 | 41,924 | 180 | 41,924 | 95 | 41,924 | ||||

| Marital status | Married | 216 | 243,680 | <0.001 | 903 | 243,680 | <0.001 | 561 | 243,680 | <0.001 |

| Not married | 204 | 181,155 | 856 | 181,155 | 529 | 181,155 | ||||

| Unknown | 49 | 19,134 | 73 | 19,134 | 40 | 19,134 | ||||

| Laterality | Left | 237 | 224,866 | <0.001 | 959 | 224,866 | 0.446 | 614 | 224,866 | 0.066 |

| Right | 226 | 218,611 | 872 | 218,611 | 516 | 218,611 | ||||

| Paired site | 6 | 409 | 1 | 409 | 0 | 409 | ||||

| Unknown | 0 | 84 | 0 | 84 | 0 | 84 | ||||

| Tumor size (cm) | <2 | 54 | 25,463 | <0.001 | 41 | 25,463 | <0.001 | 20 | 25,463 | <0.001 |

| 2.1–5 | 249 | 280,120 | 1098 | 280,120 | 672 | 280,120 | ||||

| >5 | 9 | 7136 | 28 | 7136 | 6 | 7136 | ||||

| Unknown | 157 | 131,251 | 665 | 131,251 | 432 | 131,251 | ||||

| Lymph node status | Negative | 158 | 257,428 | <0.001 | 807 | 287,428 | <0.001 | 645 | 257,428 | 0.539 |

| Positive | 311 | 186,542 | 1025 | 186542 | 485 | 186,542 | ||||

| Grade | I | 11 | 84,295 | <0.001 | 113 | 84,295 | <0.001 | 17 | 84,295 | <0.001 |

| II | 23 | 176,027 | 526 | 176,027 | 108 | 176,027 | ||||

| III | 41 | 160,309 | 1003 | 160,309 | 396 | 160,309 | ||||

| IV | 3 | 5015 | 44 | 5015 | 237 | 5015 | ||||

| Unknown | 391 | 18,324 | 146 | 18,324 | 372 | 18,324 | ||||

| AJCC stage | 0 | 83 | 5 | <0.001 | 4 | 5 | <0.001 | 160 | 5 | <0.001 |

| I | 11 | 70,594 | 153 | 70,594 | 19 | 70,594 | ||||

| II | 2 | 42,900 | 106 | 42,900 | 11 | 42,900 | ||||

| III | 4 | 13,995 | 95 | 13,995 | 3 | 13,995 | ||||

| IV | 3 | 6346 | 21 | 6346 | 1 | 6346 | ||||

| Unknown | 366 | 310,130 | 1453 | 310,130 | 936 | 310,130 | ||||

| ER status | Negative | 74 | 92,846 | <0.001 | 769 | 92,846 | <0.001 | 408 | 92,846 | <0.001 |

| Positive | 67 | 318,298 | 849 | 318,298 | 237 | 318,298 | ||||

| Borderline | 0 | 701 | 11 | 701 | 1 | 701 | ||||

| Unknown | 328 | 32,125 | 203 | 32,125 | 484 | 32,125 | ||||

| PR status | Negative | 95 | 136,827 | <0.001 | 983 | 136,827 | <0.001 | 467 | 136,827 | <0.001 |

| Positive | 37 | 268,719 | 613 | 268,719 | 138 | 268,719 | ||||

| Borderline | 0 | 2063 | 11 | 2063 | 2 | 2063 | ||||

| Unknown | 337 | 36,361 | 225 | 36,361 | 523 | 36,361 | ||||

| HER2 status | Negative | 7 | 106,696 | <0.001 | 123 | 106,696 | <0.001 | 7 | 106,696 | <0.001 |

| Positive | 17 | 21,261 | 210 | 21,261 | 33 | 21,261 | ||||

| Borderline | 0 | 3124 | 8 | 3124 | 3 | 3124 | ||||

| Unknown | 445 | 312,889 | 1491 | 312,889 | 1087 | 312,889 | ||||

| Radiation | No | 384 | 215,199 | <0.001 | 1348 | 215,199 | <0.001 | 918 | 215,199 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 67 | 213,217 | 435 | 213,217 | 191 | 213,217 | ||||

| Unknown | 18 | 15,554 | 49 | 15,554 | 21 | 15,554 | ||||

AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; ER, estrogen receptor; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; IDC, infiltrating duct carcinoma; PD‐IDC, Paget disease concomitant infiltrating duct carcinoma; PD‐DCIS, Paget disease concomitant intraductal carcinoma, unmarried group included divorced, separated, single (never married), and widowed.

Table 2 presents the distribution of characteristics of women with breast cancer stratified by marital status. For patients with PD, the clinicopathologic characteristics were age at diagnosis (P = 0.002), race (P = 0.027), laterality (P = 0.004), tumor size (P < 0.001), lymph node status (P = 0.001) and radiation situation (P < 0.001). The hormone status did not have statistical significance. However, according to the analyses, patients who were diagnosed with PD‐IDC had different statistical factors. The hormone status had statistical significance—ER status (P = 0.01), PR status (P = 0.006), and HER2 status (P = 0.025). Meanwhile, for patients with PD‐DCIS, the associations were different again. Among the three hormones, only HER2 had statistical significance (P = 0.01). Other characteristics were age (P < 0.001), race (P = 0.012), and AJCC stage (P < 0.001). Be differ from the other two subtypes, the marital status of patients with PD‐DCIS had no significant correction with the radiation status.

Table 2.

The association between clinical characteristics of Paget disease and marital status

| Categories | Married (n) | Unmarried (n) | Unknown (n) | P‐value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD | |||||

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 18–49 | 69 | 36 | 9 | 0.002 |

| 50–79 | 147 | 168 | 40 | ||

| Race | White | 187 | 170 | 36 | 0.027 |

| Black | 16 | 24 | 5 | ||

| Other | 13 | 10 | 8 | ||

| Laterality | Left | 109 | 113 | 15 | 0.004 |

| Right | 107 | 86 | 33 | ||

| Paired site | 0 | 5 | 1 | ||

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Tumor size (cm) | <2 | 16 | 25 | 13 | <0.001 |

| 2.1–5 | 134 | 101 | 14 | ||

| >5 | 0 | 5 | 4 | ||

| Unknown | 66 | 73 | 18 | ||

| Lymph node status | Negative | 84 | 69 | 5 | 0.001 |

| Positive | 132 | 135 | 44 | ||

| Grade | I | 6 | 5 | 0 | 0.523 |

| II | 10 | 13 | 0 | ||

| III | 22 | 14 | 5 | ||

| IV | 2 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Unknown | 176 | 171 | 44 | ||

| AJCC stage | 0 | 49 | 28 | 6 | 0.177 |

| I | 7 | 3 | 1 | ||

| II | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| III | 2 | 2 | 0 | ||

| IV | 2 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Unknown | 156 | 169 | 41 | ||

| ER status | Negative | 33 | 34 | 7 | 0.249 |

| Positive | 38 | 26 | 3 | ||

| Borderline | 145 | 144 | 39 | ||

| Unknown | 216 | 204 | 49 | ||

| PR status | Negative | 48 | 39 | 8 | 0.641 |

| Positive | 18 | 17 | 2 | ||

| Borderline | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Unknown | 150 | 148 | 39 | ||

| HER2 status | Negative | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0.695 |

| Positive | 10 | 6 | 1 | ||

| Borderline | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Unknown | 202 | 195 | 48 | ||

| Radiation | No | 174 | 173 | 37 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 36 | 27 | 4 | ||

| Unknown | 6 | 4 | 8 | ||

| PD‐IDC | |||||

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 18–49 | 407 | 240 | 18 | <0.001 |

| 50–79 | 496 | 616 | 55 | ||

| Race | White | 740 | 653 | 53 | <0.001 |

| Black | 58 | 137 | 11 | ||

| Other | 105 | 66 | 9 | ||

| Laterality | Left | 481 | 443 | 35 | 0.715 |

| Right | 422 | 412 | 38 | ||

| Paired site | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Tumor size (cm) | <2 | 14 | 23 | 4 | 0.189 |

| 2.1–5 | 553 | 506 | 39 | ||

| >5 | 14 | 14 | 0 | ||

| Unknown | 322 | 313 | 30 | ||

| Lymph node status | Negative | 407 | 366 | 34 | 0.562 |

| Positive | 496 | 490 | 39 | ||

| Grade | I | 43 | 67 | 3 | 0.169 |

| II | 266 | 236 | 24 | ||

| III | 498 | 469 | 36 | ||

| IV | 25 | 18 | 1 | ||

| Unknown | 71 | 66 | 9 | ||

| AJCC stage | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0.411 |

| I | 86 | 60 | 7 | ||

| II | 45 | 58 | 3 | ||

| III | 49 | 41 | 5 | ||

| IV | 13 | 8 | 0 | ||

| Unknown | 709 | 686 | 58 | ||

| ER status | Negative | 397 | 347 | 25 | 0.01 |

| Positive | 424 | 391 | 34 | ||

| Borderline | 3 | 8 | 0 | ||

| Unknown | 79 | 110 | 14 | ||

| PR status | Negative | 492 | 456 | 35 | 0.006 |

| Positive | 314 | 279 | 20 | ||

| Borderline | 5 | 4 | 2 | ||

| Unknown | 92 | 117 | 16 | ||

| HER2 status | Negative | 56 | 63 | 4 | 0.025 |

| Positive | 114 | 88 | 8 | ||

| Borderline | 5 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Unknown | 728 | 704 | 59 | ||

| Radiation | No | 634 | 660 | 45 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 244 | 174 | 17 | ||

| Unknown | 16 | 22 | 11 | ||

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 18–49 | 407 | 240 | 18 | <0.001 |

| 50–79 | 496 | 616 | 55 | ||

| Race | White | 740 | 653 | 53 | <0.001 |

| Black | 58 | 137 | 11 | ||

| Other | 105 | 66 | 9 | ||

| Laterality | Left | 481 | 443 | 35 | 0.715 |

| Right | 422 | 412 | 38 | ||

| Paired site | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Tumor size (cm) | <2 | 14 | 23 | 4 | 0.189 |

| 2.1–5 | 553 | 506 | 39 | ||

| >5 | 14 | 14 | 0 | ||

| Unknown | 322 | 313 | 30 | ||

| Lymph node status | Negative | 407 | 366 | 34 | 0.562 |

| Positive | 496 | 490 | 39 | ||

| Grade | I | 43 | 67 | 3 | 0.169 |

| II | 266 | 236 | 24 | ||

| III | 498 | 469 | 36 | ||

| IV | 25 | 18 | 1 | ||

| Unknown | 71 | 66 | 9 | ||

| AJCC stage | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0.411 |

| I | 86 | 60 | 7 | ||

| II | 45 | 58 | 3 | ||

| III | 49 | 41 | 5 | ||

| IV | 13 | 8 | 0 | ||

| Unknown | 709 | 686 | 58 | ||

| ER status | Negative | 397 | 347 | 25 | 0.01 |

| Positive | 424 | 391 | 34 | ||

| Borderline | 3 | 8 | 0 | ||

| Unknown | 79 | 110 | 14 | ||

| PR status | Negative | 492 | 456 | 35 | 0.006 |

| Positive | 314 | 279 | 20 | ||

| Borderline | 5 | 4 | 2 | ||

| Unknown | 92 | 117 | 16 | ||

| HER2 status | Negative | 56 | 63 | 4 | 0.025 |

| Positive | 114 | 88 | 8 | ||

| Borderline | 5 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Unknown | 728 | 704 | 59 | ||

| Radiation | No | 634 | 660 | 45 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 244 | 174 | 17 | ||

| Unknown | 16 | 22 | 11 | ||

AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; ER, estrogen receptor; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; IDC, infiltrating duct carcinoma; PD‐IDC, Paget disease concomitant infiltrating duct carcinoma; PD‐DCIS, Paget disease concomitant intraductal carcinoma, unmarried group included divorced, separated, single (never married), and widowed.

Comparison of survival between three subtypes of Paget disease and IDC

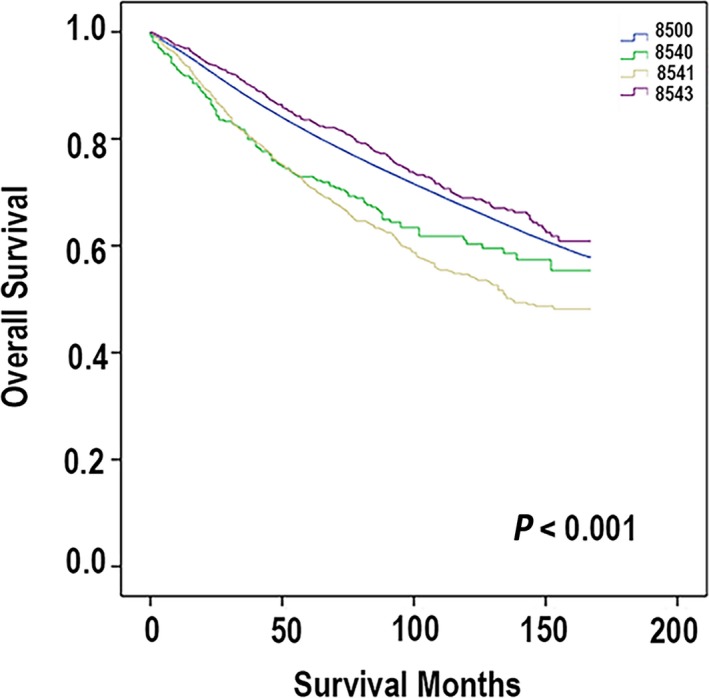

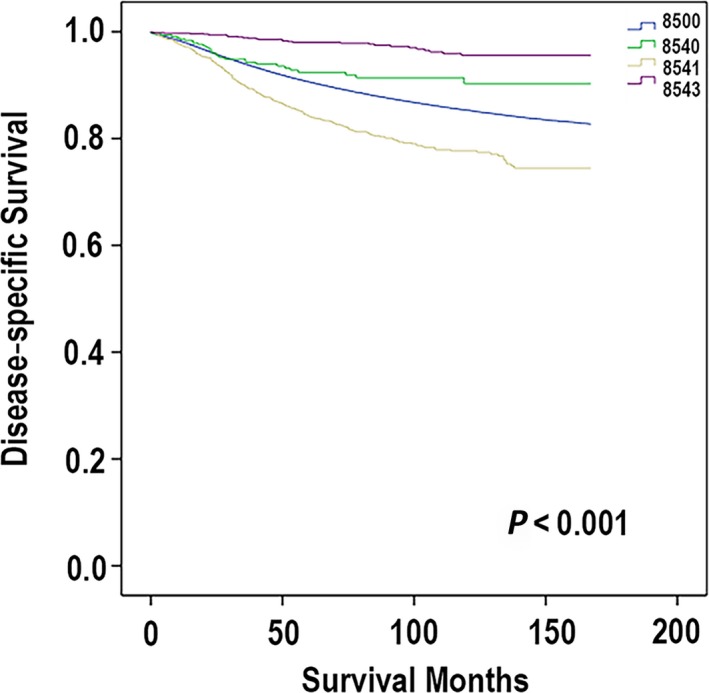

Utilizing the Kaplan–Meier method, we analyzed all these four subtypes (PD, PD‐IDC, PD‐DCIS, and IDC) of mammary carcinoma. On the basis of the OS, the different outcomes of four subtypes of breast carcinoma are shown distinctly in Figure 1. Patients with PD‐DCIS had the best prognosis with a 5‐year OS 83.6%. The one worse than the PD‐DCIS was IDC. The 5‐year OS of patients with IDC was 81.1%. Then, the next one was PD. The 5‐year OS of patients with PD was 72.9%. The one with worst outcomes was PD‐IDC, whose 5‐year OS was 71.4%. Then, we analyzed the cases utilizing the DSS, and the comparison of different kinds of mammary cancer is shown in Figure 2. The patients with PD‐DCIS had the best prognosis with a 5‐year survival rate of 98.2%. The worse one was patients with PD. Its 5‐year survival rate was 92.4%. The survival rate of patients with IDC was 91%. And patients who were diagnosed with PD‐IDC had the worst outcomes. Its 5‐year survival rate was 84.1%. Apparently, the results of the analyses based on the OS and DSS had a little difference. Based on the OS, the results showed that the prognosis of PD was worse than IDC. However, based on the DSS, the outcome of the IDC was worse than PD. Meanwhile, the prognostic indicators can be found during the univariate analysis.

Figure 1.

According to the ICD‐O‐3, the codes are defined: code 8500 (ductal carcinoma), code 8540 (mammary Paget disease), code 8541 (Paget disease with infiltrating ductal carcinoma), and code 8543 (Paget disease with intraductal carcinoma). Overall survival (OS) was measured from the date on which the first‐time definite diagnosis was made until the date of death, the date last known to be alive, or September 2013.

Figure 2.

According to the ICD‐O‐3, the codes are defined: code 8500 (ductal carcinoma), code 8540 (mammary Paget disease), code 8541 (Paget disease with infiltrating ductal carcinoma), and code 8543 (Paget disease with intraductal carcinoma). Disease‐specific survival (DSS) was measured from the date of diagnosis to the date of death which is associated with breast carcinoma.

The survival analyses in subtypes of Paget disease

According to the Kaplan–Meier method and compared utilizing the log‐rank test, we analyzed the Paget disease and its indicator which were associated with the prognosis. The results of the analyses are shown in Table 3. For PD, indicators which had significance were age at diagnosis (P < 0.001), marital status (P < 0.001), tumor size (P < 0.001), lymph node status (P < 0.001), and AJCC stage (P < 0.001). For PD‐IDC, the significant indicators were age at diagnosis, marital status, tumor size, lymph node status, Grade, AJCC stage, and ER status. Meanwhile, the significant indicators of PD‐DCIS were age at diagnosis (P < 0.001), marital status (P < 0.001), tumor size (P < 0.001), lymph node status (P < 0.001), AJCC stage (P < 0.001), HER2 status (P < 0.001), and radiation or not (P = 0.007).

Table 3.

Survival analyses–univariate analyses of Paget disease

| PD | PD‐IDC | PD‐DCIS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Category | P‐value | Variables | Category | P‐value | Variables | Category | P‐value |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 18–49 | <0.001 | Age at diagnosis (years) | 18–49 | <0.001 | Age at diagnosis (years) | 18–49 | <0.001 |

| 50–79 | 50–79 | 50–79 | ||||||

| Race | White | 0.052 | Race | White | 0.296 | Race | White | 0.253 |

| Black | Black | Black | ||||||

| Other | Other | Other | ||||||

| Marital status | Married | <0.001 | Marital status | Married | <0.001 | Marital status | Married | <0.001 |

| Not married | Not married | Not married | ||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

| Laterality | Left | 0.112 | Laterality | Left | 0.561 | Laterality | Left | 0.162 |

| Right | Right | Right | ||||||

| Paired site | Paired site | Paired site | ||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

| Tumor size (cm) | <2 | <0.001 | Tumor size (cm) | <2 | <0.001 | Tumor size (cm) | <2 | <0.001 |

| 2.1–5 | 2.1–5 | 2.1–5 | ||||||

| >5 | >5 | >5 | ||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

| Lymph node status | Negative | <0.001 | Lymph node status | Negative | <0.001 | Lymph node status | Negative | <0.001 |

| Positive | Positive | Positive | ||||||

| Grade | I | 0.069 | Grade | I | 0.016 | Grade | I | 0.313 |

| II | II | II | ||||||

| III | III | III | ||||||

| IV | IV | IV | ||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

| AJCC stage | 0 | <0.001 | AJCC stage | 0 | <0.001 | AJCC stage | 0 | <0.001 |

| I | I | I | ||||||

| II | II | II | ||||||

| III | III | III | ||||||

| IV | IV | IV | ||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

| ER status | Negative | 0.954 | ER status | Negative | 0.004 | ER status | Negative | 0.363 |

| Positive | Positive | Positive | ||||||

| Borderline | Borderline | Borderline | ||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

| PR status | Negative | 0.758 | PR status | Negative | 0.055 | PR status | Negative | 0.565 |

| Positive | Positive | Positive | ||||||

| Borderline | Borderline | Borderline | ||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

| HER2 status | Negative | 0.161 | HER2 status | Negative | 0.348 | HER2 status | Negative | <0.001 |

| Positive | Positive | Positive | ||||||

| Borderline | Borderline | Borderline | ||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

| Radiation | No | 0.085 | Radiation | No | 0.077 | Radiation | No | 0.007 |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; ER, estrogen receptor; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; IDC, infiltrating duct carcinoma; PD‐IDC, Paget disease concomitant infiltrating duct carcinoma; PD‐DCIS, Paget disease concomitant intraductal carcinoma, unmarried group included divorced, separated, single (never married), and widowed.

Using Cox regression analysis was performed to compute hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals. Choosing the variates which were significant in the univariate analyses, the multivariate analysis was performed. And the results are shown in Table 4. For PD, significant indicators of prognosis were age at diagnosis (P = 0.005, HR = 0.449, 95% CI, 0.257–0.787), race (P = 0.014), marital status (P < 0.001), tumor size (P = 0.033), lymph node status (P < 0.001, positive, HR = 0.417, 95% CI, 0.264–0.658), and Grade (P = 0.042). The P‐value of AJCC stage was larger than 0.05 (P = 0.203). For PD‐IDC, variates which had prognostic significance were age at diagnosis (P < 0.001, HR = 0.347, 95% CI, 0.283–0.425), marital status (P < 0.001), tumor size (P < 0.001), lymph node status (P < 0.001, positive, HR = 0.437, 95% CI, 0.366–0.522), Grade (P = 0.049), AJCC stage (P < 0.001), and ER status (P = 0.034, positive, HR = 0.453, 95% CI, 0.195–1.052). The statistic significant indicators of the patients with PD‐DCIS were age at diagnosis (P < 0.001, HR = 0.309, 95% CI, 0.203–0.469), marital status (P < 0.001, not married, HR = 0.504, 95% CI, 0.269–0.945), tumor size (P < 0.001), lymph node status (P < 0.001, positive, HR = 0.546, 95% CI, 0.424–0.704), HER2 status (P = 0.004, positive, HR = 9.502, 95% CI, 2.758–32.734), and radiation or not P = 0.001, yes, HR = 2.183, 95% CI, 0.688–6.922).

Table 4.

Survival analyses–multivariate analyses of Paget disease

| Variables | Category | Hazard ratio | 95% Confidence interval | P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD | ||||

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 18–49 | 1 | Referent | 0.005 |

| 50–79 | 0.449 | 0.257–0.787 | ||

| Race | White | 1 | Referent | 0.014 |

| Black | 3.772 | 1.366–10.413 | ||

| Other | 5.495 | 1756–17.2 | ||

| Marital status | Married | 1 | Referent | <0.001 |

| Not married | 0.379 | 0.214–0.672 | ||

| Unknown | 0.887 | 0.528–1.491 | ||

| Tumor size (cm) | <2 | 1 | Referent | 0.033 |

| 2.1–5 | 1.417 | 0.806–2.494 | ||

| >5 | 0.651 | 0.429–0.988 | ||

| Unknown | 1.506 | 0.509–4.454 | ||

| Lymph node status | Negative | 1 | Referent | <0.001 |

| Positive | 0.417 | 0.264–0.658 | ||

| Grade | I | 1 | Referent | 0.042 |

| II | 1.065 | 0.3–2.86 | ||

| III | 2.537 | 1.239–5.139 | ||

| IV | 0.714 | 0.313–1.628 | ||

| Unknown | 1.404 | 0.189–10.436 | ||

| AJCC stage | 0 | 1 | Referent | 0.203 |

| I | 0.795 | 0.353–1.793 | ||

| II | 0 | 0 | ||

| III | 0 | 0 | ||

| IV | 1.613 | 0.204–12.763 | ||

| Unknown | 5.224 | 1.449–18.837 | ||

| PD‐IDC | ||||

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 18–49 | 1 | Referent | <0.001 |

| 50–79 | 0.347 | 0.283–0.425 | ||

| Race | White | 1 | Referent | 0.77 |

| Black | 0.556 | 0.813–1.47 | ||

| Other | 0.472 | 0.795–1.643 | ||

| Marital status | Married | 1 | Referent | <0.001 |

| Not married | 0.625 | 0.427–0.914 | ||

| Unknown | 1.053 | 0.728–1.523 | ||

| Tumor size (cm) | <2 | 1 | Referent | <0.001 |

| 2.1–5 | 2.537 | 1.662–3.873 | ||

| >5 | 0.915 | 0.769–1.088 | ||

| Unknown | 1.255 | 0.685–2.302 | ||

| Lymph node status | Negative | 1 | Referent | <0.001 |

| Positive | 0.437 | 0.366–0.522 | ||

| Grade | I | 1 | Referent | 0.049 |

| II | 0.696 | 0.439–1.103 | ||

| III | 0.946 | 0.683–1.311 | ||

| IV | 1.155 | 0.855–1.561 | ||

| Unknown | 0.855 | 0.705–2.256 | ||

| AJCC stage | 0 | 1 | Referent | <0.001 |

| I | 0 | 0 | ||

| II | 0.548 | 0.256–1.172 | ||

| III | 0.67 | 0.329–1.364 | ||

| IV | 1.055 | 0.632–1.764 | ||

| Unknown | 4.754 | 2.48–9.112 | ||

| ER status | Negative | 1 | Referent | 0.034 |

| Positive | 0.453 | 0.195–1.052 | ||

| Borderline | 0.438 | 0.19–1.007 | ||

| Unknown | 1.329 | 0.373–4.732 | ||

| PR status | Negative | 1 | Referent | 0.212 |

| Positive | 2.12 | 0.931–4.827 | ||

| Borderline | 1.818 | 0.799–4.138 | ||

| Unknown | 2.477 | 0.66–9.29 | ||

| PD‐DCIS | ||||

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 18–49 | 1 | Referent | <0.001 |

| 50–79 | 0.309 | 0.203–0.469 | ||

| Race | White | 1 | Referent | 0.63 |

| Black | 1.058 | 0.619–1.808 | ||

| Other | 1.288 | 0.67–2.475 | ||

| Marital status | Married | 1 | Referent | <0.001 |

| Not married | 0.504 | 0.269–0.945 | ||

| Unknown | 1.237 | 0.675–2.266 | ||

| Tumor size (cm) | <2 | 1 | Referent | <0.001 |

| 2.1–5 | 4.82 | 2.351–9.88 | ||

| >5 | 1.035 | 0.772–1.388 | ||

| Unknown | 1.617 | 0.218–11.983 | ||

| Lymph node status | Negative | 1 | Referent | <0.001 |

| Positive | 0.546 | 0.424–0.704 | ||

| Grade | I | 1 | Referent | 0.332 |

| II | 0.35 | 0.085–1.447 | ||

| III | 0.74 | 0.457–1.198 | ||

| IV | 0.891 | 0.663–1.198 | ||

| Unknown | 0.786 | 0.569–1.088 | ||

| ER status | Negative | 1 | Referent | 0.3 |

| Positive | 1.424 | 0.759–2.672 | ||

| Borderline | 0.922 | 0.486–1.749 | ||

| Unknown | 0.968 | 0.23–14.54 | ||

| PR status | Negative | 1 | Referent | 0.898 |

| Positive | 0.857 | 0.467–1.574 | ||

| Borderline | 1.047 | 0.513–2.134 | ||

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | ||

| HER2 status | Negative | 1 | Referent | 0.004 |

| Positive | 9.502 | 2.758–32.734 | ||

| Borderline | 0.614 | 0.084–4.466 | ||

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | ||

| Radiation | No | 1 | Referent | 0.001 |

| Yes | 2.183 | 0.688–6.922 | ||

| Unknown | 1.096 | 0.33–3.638 | ||

AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; ER, estrogen receptor; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; IDC, infiltrating duct carcinoma; PD‐IDC, Paget disease concomitant infiltrating duct carcinoma; PD‐DCIS, Paget disease concomitant intraductal carcinoma, unmarried group included divorced, separated, single (never married), and widowed.

The association between Paget disease and patient's marital status

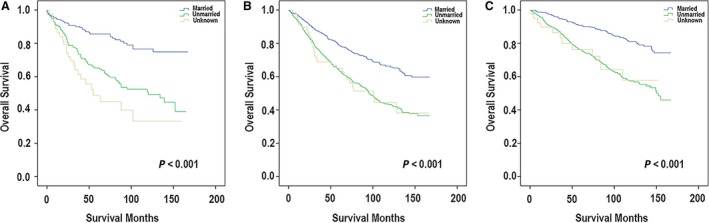

According to the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the log‐rank test, we analyzed the Paget disease and the marital status. And Figure 3 presents the correlation. For patients with PD (Fig. 3A), the married patients had the best prognosis with a 5‐year OS of 85.6%. The unmarried patients (included single patients who never married, widowed, divorced, and separated patients) had worse outcomes with a 5‐year OS of 65.2%. Patients whose marital status was unknown had the worst diagnosis with a 5‐year OS of 48.7%. And the difference between them had statistical significance (P < 0.001). For patients who were diagnosed with PD‐IDC (Fig. 3B), the married patients had the best prognosis with a 5‐year OS of 78.7%. The next was patients who were unmarried with a 5‐year OS of 64.1%. For this subtype, the patients whose marital status was unknown had the almost similar 5‐year OS of 64.9%. And the difference was statistically significant as well (P < 0.001). For patients with PD‐DCIS (Fig. 3C), the 5‐year OS was 90.8% (married), 76.3% (unmarried), and 76.2% (unknown).

Figure 3.

According to the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the log‐rank test, we analyzed the Paget disease and the marital status. (A) The association between marital status and clinical prognosis in patients with PD. (B) The association between marital status and clinical prognosis in patients with PD‐IDC. (C) The association between marital status and clinical prognosis in patients with PD‐DCIS.

Discussion

Previous study had reported that patients who were diagnosed of Paget disease with underlying invasive cancer had poor tumor characteristics 15. A previous research showed that the Paget disease with underlying invasive cancer had tumors with Grade 3 histology 8. In 1881, Thin observed that the nipple lesion contained malignant cells which were correlated to the underlying cancer 16. And this observation suggested the process of intraductal extension of cancer through the major lactiferous sinuses. We call it “pagetoid spread” nowadays. Histologically, Paget cells are large cells with pale, clear cytoplasm. It has enlarged nucleoli located within the epidermis and along the basal layer. The most widely accepted hypothesis to explain the origin of Paget cells is the epidermotropic theory. And this theory considered that Paget cells are derived from an underlying mammary adenocarcinoma 17. Evidence supporting the epidermotropic theory is based on studies showing that Paget disease is associated with an underlying breast carcinoma in most patients 18, 19, 20. Binding of heregulin to its receptor on Paget cells can induce chemotaxis of these breast cancer cells, and the cells eventually migrate into the overlying nipple epidermis 21. It is noteworthy that Paget cells and the underlying associated ductal carcinoma share the same immunohistochemical profile 22 and the same patterns of gene expression.

In allusion to different subtype of Paget disease, we found that the significantly associated indicators were different. Unmarried patients of PD, including those who were widowed, divorced, and never married, were at significantly great risk of existing lymph node metastasis. Meanwhile, for patients of PD‐IDC, we found that the hormone status was related to the human epidermal growth factor receptor II. However, for the patients with PD‐DCIS, only human epidermal growth factor receptor II had statistical significance. The association between marital status and these indicators was significant for every malignancy evaluated. Previous studies have linked marriage to improvements in cardiovascular, endocrine, and immune function, and marriage may be a determinant of the magnitude and presence of this effect 23, 24. Cortisol levels seem to be lower in patients with cancer who have adequate support networks, and diurnal cortisol patterns have been linked with natural killer cell count and survival in patients with cancer25, 26, potentially providing a physiologic basis for the psychologically based data described previously 27. Further investigations on this subject are warranted.

However, the study also had some limitations. The SEER database did not give us enough information about the lymphovascular invasion which can be regarded as the prediction of lymph node metastasis. Besides, the follow‐up of many patients was limited. And the information of systemic therapy of the patients was lack according to the SEER system. Based on the SEER database, the HER2 status was tested from 2010; however, the cases were from 2000 to 2013. Apparently, analyses of the HER2 were limited. And it made us unable to explore the clinical significance of HER2 status. Therefore, our study was limited by lack of some information. Besides, there is potential for misclassification of marital status. We did not take into account changes of marital status which may have occurred during the follow‐up period. And this phenomenon may have influenced our results. Thus, our findings may underestimate the protective effect that marriage has on breast cancer outcome. We defined that the single category contained divorcees, widows, and never married women. However, previous studies had found that there may be some difference among groups of unmarried women. Although the difference existed, the unmarried women fare worse than the married counterparts.

In conclusion, our study showed patients with PD‐IDC have the worst prognosis. Among all these three kinds of Paget disease, unmarried patients had worse outcomes. And the marital status of patients with PD‐IDC is associated with hormone status and HER2 status. The observation underscores the importance of individualized treatment.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the grant from National Natural Science Foundation of China (81773093, 81472669) and a Municipal Human Resources Development Program for Outstanding Leaders in Medical Disciplines in Shanghai (2017BR028).

Cancer Medicine 2018; 7(6):2307–2318

References

- 1. Delaloge, S. , Bachelot T., Bidard F. C., Espie M., Brain E., Bonnefoi H., et al. 2016. Breast cancer screening: on our way to the future. Bull. Cancer 103:753–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Karakas, C. 2011. Paget's disease of the breast. J. Carcinogenesis 10:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lohsiriwat, V. , Martella S., Rietjens M., Botteri E., Rotmensz N., Mastropasqua M. G., et al. 2012. Paget's disease as a local recurrence after nipple‐sparing mastectomy: clinical presentation, treatment, outcome, and risk factor analysis. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 19:1850–1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Inglis, K. 1946. Paget's disease of the nipple; with special reference to the changes in the ducts. Am. J. Pathol. 22:1–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yim, J. H. , Wick M. R., Philpott G. W., Norton J. A., and Doherty G. M.. 1997. Underlying pathology in mammary Paget's disease. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 4:287–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen, C. Y. , Sun L. M., and Anderson B. O.. 2006. Paget disease of the breast: changing patterns of incidence, clinical presentation, and treatment in the U.S. Cancer 107:1448–1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wong, S. M. , Freedman R. A., Sagara Y., Stamell E. F., Desantis S. D., Barry W. T., et al. 2015. The effect of Paget disease on axillary lymph node metastases and survival in invasive ductal carcinoma. Cancer 121:4333–4340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kothari, A. , Hamed H., Beechey‐Newman N., D'Arrigo C., Hanby A., Ryder K., et al. 2002. Paget disease of the nipple: a multifocal manifestation of higher‐risk disease. Cancer 95:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bennett, T. 1992. Marital status and infant health outcomes. Soc. Sci. Med. 35:1179–1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Johnson, N. J. , Backlund E., Sorlie P. D., and Loveless C. A.. 2000. Marital status and mortality: the national longitudinal mortality study. Ann. Epidemiol. 10:224–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Eskander, M. F. , Schapira E. F., Bliss L. A., Burish N. M., Tadikonda A., Ng S. C., et al. 2016. Keeping it in the family: the impact of marital status and next of kin on cancer treatment and survival. Am. J. Surg. 212:691–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Goodwin, J. S. , Hunt W. C., Key C. R., and Samet J. M.. 1987. The effect of marital status on stage, treatment, and survival of cancer patients. JAMA 258:3125–3130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lillard, L. A. , and Panis C. W.. 1996. Marital status and mortality: the role of health. Demography 33:313–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kravdal, O. 2001. The impact of marital status on cancer survival. Soc. Sci. Med. 52:357–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wolber, R. A. , Dupuis B. A., and Wick M. R.. 1991. Expression of c‐erbB‐2 oncoprotein in mammary and extramammary Paget's disease. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 96:243–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rzaca, M. , and Tarkowski R.. 2013. Paget's disease of the nipple treated successfully with cryosurgery: a series of cases report. Cryobiology 67:30–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jahn, H. , Osther P. J., Nielsen E. H., Rasmussen G., and Andersen J.. 1995. An electron microscopic study of clinical Paget's disease of the nipple. APMIS 103:628–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Paone, J. F. , and Baker R. R.. 1981. Pathogenesis and treatment of Paget's disease of the breast. Cancer 48:825–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ashikari, R. , Park K., Huvos A. G., and Urban J. A.. 1970. Paget's disease of the breast. Cancer 26:680–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dixon, A. R. , Galea M. H., Ellis I. O., Elston C. W., and Blamey R. W.. 1991. Paget's disease of the nipple. Br. J. Surg. 78:722–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schelfhout, V. R. , Coene E. D., Delaey B., Thys S., Page D. L., and De Potter C. R.. 2000. Pathogenesis of Paget's disease: epidermal heregulin‐alpha, motility factor, and the HER receptor family. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 92:622–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Anderson, J. M. , Ariga R., Govil H., Bloom K. J., Francescatti D., Reddy V. B., et al. 2003. Assessment of Her‐2/Neu status by immunohistochemistry and fluorescence in situ hybridization in mammary Paget disease and underlying carcinoma. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. 11:120–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gallo, L. C. , Troxel W. M., Matthews K. A., and Kuller L. H.. 2003. Marital status and quality in middle‐aged women: Associations with levels and trajectories of cardiovascular risk factors. Health Psychol. 22:453–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Herberman, R. B. , and Ortaldo J. R.. 1981. Natural killer cells: their roles in defenses against disease. Science 214:24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sephton, S. E. , Lush E., Dedert E. A., Floyd A. R., Rebholz W. N., Dhabhar F. S., et al. 2013. Diurnal cortisol rhythm as a predictor of lung cancer survival. Brain Behav. Immun. 30(Suppl):S163–S170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sephton, S. E. , Sapolsky R. M., Kraemer H. C., and Spiegel D.. 2000. Diurnal cortisol rhythm as a predictor of breast cancer survival. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 92:994–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Turner‐Cobb, J. M. , Sephton S. E., Koopman C., Blake‐Mortimer J., and Spiegel D.. 2000. Social support and salivary cortisol in women with metastatic breast cancer. Psychosom. Med. 62:337–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]