Abstract

In the past decade, iron oxide nanoparticles (IONPs) have attracted more and more attention for their excellent physicochemical properties and promising biomedical applications. In this review, we summarize and highlight recent progress in the design, synthesis, biocompatibility evaluation and magnetic theranostic applications of IONPs, with a special focus on cancer treatment. Firstly, we provide an overview of the controlling synthesis strategies for fabricating zero-, one- and three-dimensional IONPs with different shapes, sizes and structures. Then, the in vitro and in vivo biocompatibility evaluation and biotranslocation of IONPs are discussed in relation to their chemo-physical properties including particle size, surface properties, shape and structure. Finally, we also highlight significant achievements in magnetic theranostic applications including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), magnetic hyperthermia and targeted drug delivery. This review provides a background on the controlled synthesis, biocompatibility evaluation and applications of IONPs as cancer theranostic agents and an overview of the most up-to-date developments in this area.

Keywords: iron oxide, controlled synthesis, biocompatibility, magnetic theranostics

Introduction

Iron oxide nanoparticles (IONPs) are widespread in the natural environment and living systems, such as in magnetotactic bacteria 1, fish 2, and birds 3, and can be readily synthesized in the laboratory 4. During the past decades, IONPs have received tremendous attention in biomedicine applications such as drug delivery, magnetic hyperthermia, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), tissue repair, magnetic separation, magnetic transfection, iron detection, chelation therapy and cancer theranostics 5. IONPs are a class of excellent nano-medical materials due to their superparamagnetism, high magnetic moments, extra magnetic anisotropy contribution, irreversibility of high-field magnetization, high surface area, magnetothermal effect, and ideal biocompatibility 6-9. The three most common structures of IONPs are magnetite (Fe3O4), hematite (α-Fe2O3) and maghemite (γ-Fe2O3); among them, Fe3O4 nanoparticles are of great interest for in vivo and clinical applications due to their superparamagnetic property, which has no remaining magnetism after removal of the magnetic field. Therefore, all the IONPs we mention in this review particularly refer to Fe3O4 nanoparticles.

The increasing application of IONPs in biomedicine has aroused special interest in fabrication protocols for high-performance nanoparticles, including controlled synthesis of IONPs with various morphologies, sizes and structures, and synthetic technology for the scale-up production and necessary surface modifications of the nanoparticles for improved biocompatibility. It has been well acknowledged that not only physiochemical properties but also biocompatibility of as-synthesized IONPs can be pertinently affected by the morphology, size, structure, and surface properties of the particles 8-12. Biocompatibility of the IONPs is regarded as the preliminary requirement and of critical significance for their application in biomedical applications. Both in vitro and in vivo analyses should be carefully conducted to evaluate the biocompatibility for IONPs. While in vitro cytotoxicity tests mainly cover assays for cell viability/proliferation/differentiation, microscopic analysis of intracellular location, in vitro hemolysis and genotoxicity assays, and in vivo analysis may provide information on pharmacokinetics aspects after administration of the IONPs, including blood compatibility, biodistribution, metabolism and clearance 13-15. Putting together the biocompatibility analyses provides comprehensive information on the effect of the IONPs on cell fate and in vivo response 16, 17.

Cancer magnetic theranostics, which is defined as the integration of multiple moieties into a single nano-platform based on magnetic nanoparticles for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes, has attracted increasing interest and can provide a powerful paradigm for efficient treatment against cancers 18, 19. IONP-based magnetic theranostics provides a way for us to track the theranostic agents' location, control the therapeutic process constantly, and eventually evaluate the treatment efficacy 15, 20-23. This review aims to summarize the state-of-the-art in design, biocompatibility and magnetic theranostic applications of IONPs. We focus on the shape-, size- and structure-controlled synthesis of IONPs, the biocompatibility of IONPs and relevant influenced factors, and their magnetic theranostic applications including MRI, magnetic hyperthermia and targeted drug delivery.

Shape-, size- and structure-controlled synthesis

In the last decades, much attention has been focused on the development of efficient synthesis approaches to produce shape- and size-controlled, biocompatible, and monodisperse IONPs for magnetic theranostic applications 24. The widely used methods to prepare high-quality IONPs include co-precipitation, hydrothermal synthesis, thermal decomposition, sol-gel synthesis, sonochemical synthesis, microemulsion, electrochemical synthesis, electrospray synthesis, and bacterial and microorganism synthesis 25, 26. Among all these methods, temperature and pressure during the synthesis play important roles in determining the morphology and size of the IONPs. Hydrothermal synthesis is carried out in aqueous media in reactors or autoclaves where the temperature can be higher than 200 °C and the system pressure can be more than 2000 psi 27. Thermal decomposition of metallic precursors and hydrothermal synthesis are general strategies to prepare IONPs with controlled shape, size and structure. The reaction temperature for the preparation of IONPs through thermal decomposition using iron compounds or iron precursors is usually as high as 300 °C, which is critical to control the nucleation and growth of nanoparticles from solution. Moreover, the high temperature and system pressure increase the solubility of most ionic species, which could result in uniform particles with narrow size distribution 28.

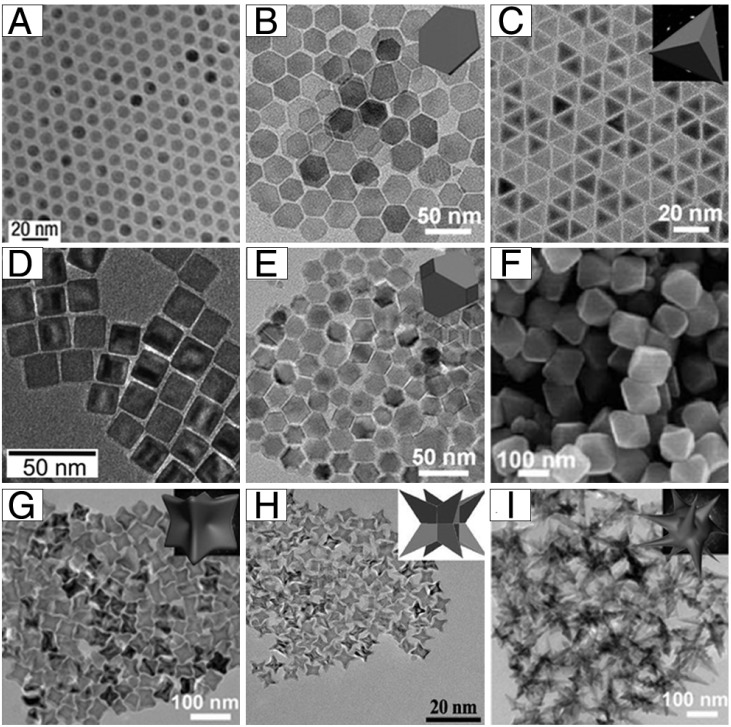

As shown in Figure 1, monodisperse IONPs with various morphologies, including nanospheres, plates, tetrahedrons, cubes, truncated octahedrons, octahedrons, concaves, Octapods, and multibranches have been successfully fabricated under different synthesis protocols. Hyeon and co-authors synthesized multi-kilograms of iron oxide nanocrystals in a single reaction through thermal decomposition (Figure 1A) 29. Inexpensive and environmentally friendly compounds (iron-oleate complex) in 1-octadecene were slowly heated to a certain temperature and aged, generating monodisperse iron oxide nanocrystals. By thermal decomposition of iron oleate in the presence of sodium oleate, Zhou et al. synthesized iron oxide nanostructures with various shapes 30. By tuning the molar ratio of sodium oleate/iron oleate or the reaction temperature, they could obtain plates, tetrahedrons, octahedrons, concaves, multibranches and self-assembled structures (Figure 1B-C, E-G, I). This also opened up a new strategy for the controlled synthesis of other metal oxide nanoparticles. Additionally, nanocubic IONPs (Figure 1D) were synthesized by thermal decomposition of iron oleate precursors in the presence of sodium oleate as a stabilizer 31. By careful adjustment of the oleic acid salts as well as the reaction temperature, a series of size- and shape-controlled cubic iron oxide nanocrystals could be obtained. Zhao et al. synthesized Octapod IONPs (Figure 1H) via decomposition of iron oleate in 1-octadecene solvent containing oleic acid as the surfactant and sodium chloride 32.

Figure 1.

Example morphologies of 0-dimensional IONPs: (A) nanospheres, (B) plates, (C) tetrahedrons, (D) cubes, (E) truncated octahedrons, (F) octahedrons, (G) concaves, (H) Octapods, and (I) multibranches. (A) Reproduced with permission from 29, copyright 2004. (B-C, E, G, I) Reproduced with permission from 30, copyright 2015. (D) Reproduced with permission from 31, copyright 2007. (F) Reproduced with permission from 33, copyright 2010. (H) Reproduced with permission from 32, copyright 2013.

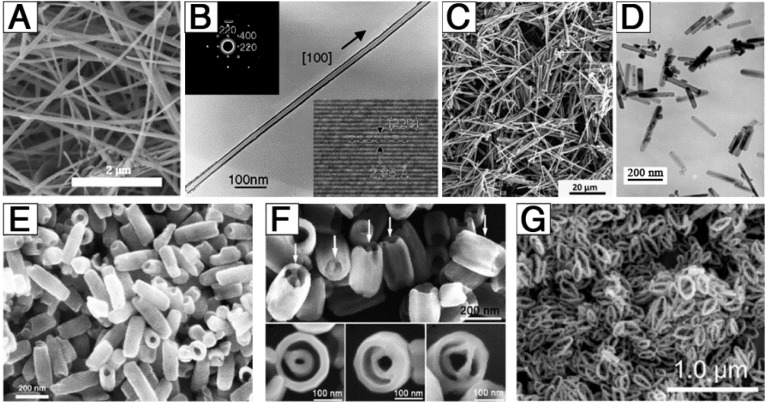

In addition to the synthesis of 0-dimensional IONPs (nanoparticles), efforts have also been applied to the development of 1-dimensional and 3-dimensional structures (Figure 2). He et al. successfully obtained uniform, ultra-thin, single-crystal Fe3O4 (Figure 2A) based on a facile, surfactant-assisted hydrothermal route with the assistance of polyethylene glycol 400 (PEG-400) 34. The as-synthesized products were nanowires with a growth direction along the 100 crystal direction, with a narrow diameter distribution centered at 15 nm and a length of up to several micrometers. Liu et al. firstly reported the synthesis of homogeneous single-crystal Fe3O4 nanotubes (Figure 2B) with controllable length, diameter, and wall thickness 35. By tuning the length and diameter of the MgO cores and the deposition time/rate of the shell using a wet-chemical etching method, the Fe3O4 nanotubes could be precisely controlled. Additionally, magnetic needle-like IONPs (Figure 2C) were developed via a microwave-assisted procedure 35, during which, microwave served as a source of energy for the formation of precursor particles with high aspect ratio and the source of heat required for the thermal decomposition. Wan et al. prepared uniform single-crystal Fe3O4 nanorods (Figure 2D) with an average diameter of 25 nm and length of 200 nm via a soft-template-assisted hydrothermal route at 120 °C for 20 h 36. Ethylenediamine was not only used as a base source but also as a soft template to form single-crystal Fe3O4 nanorods, and benzene was used to prevent oxidation of ferrous ion by oxygen in air. Through changing the ferrous ion source and solvent, single-crystal hematite nanotubes (Figure 2E) were developed via a facile, one-step hydrothermal treatment of a FeCl3 solution (0.02 M) in the presence of NH4H2PO4 (7.2×10-4 M) at 220 °C for 48 h 37. The Fe3O4 nanotubes had a single-wall tube structure with outer diameter of 90-110 nm, inner diameter of 40-80 nm, and length of 250-400 nm. Based on these results, single-crystal iron oxide tube-in-tube nanostructures (Figure 2F) were obtained in the same way 38. The structure was formed with a multisite dissolution process of ellipsoid precursors, which was also useful to achieve other complex single-crystal architectures. Furthermore, Liu et al. demonstrated a facile, inexpensive, and fast microwave-assisted hydrothermal (MAH) method for the large-scale and controllable synthesis of high-quality elliptical Fe3O4 nanorings (13-26 nm wall thickness, 1.2-2.0 long axis/short axis, and 48-213 nm long axis length) 39. These Fe3O4 nanorings exhibited significant microwave absorption, strong dielectric loss, multiresonance behaviors, oscillation resonance absorption, microantenna radiation, and interference behaviors.

Figure 2.

Example morphologies of 1-dimensional and 3-dimensional IONPs: (A) nanowires, (B) long nanotubes, (C) nanoneedles, (D) nanorods, (E) short nanotubes, (F) tube-in-tubes, and (G) nanorings. (A) Reproduced with permission from 34, copyright 2007. (B) Reproduced with permission from 35, copyright 2005. (C) Reproduced with permission from 40, copyright 2015. (D) Reproduced with permission from 36, copyright 2005. (E) Reproduced with permission from 37, copyright 2005. (F) Reproduced with permission from 38, copyright 2007. (G) Reproduced with permission from 39, copyright 2016.

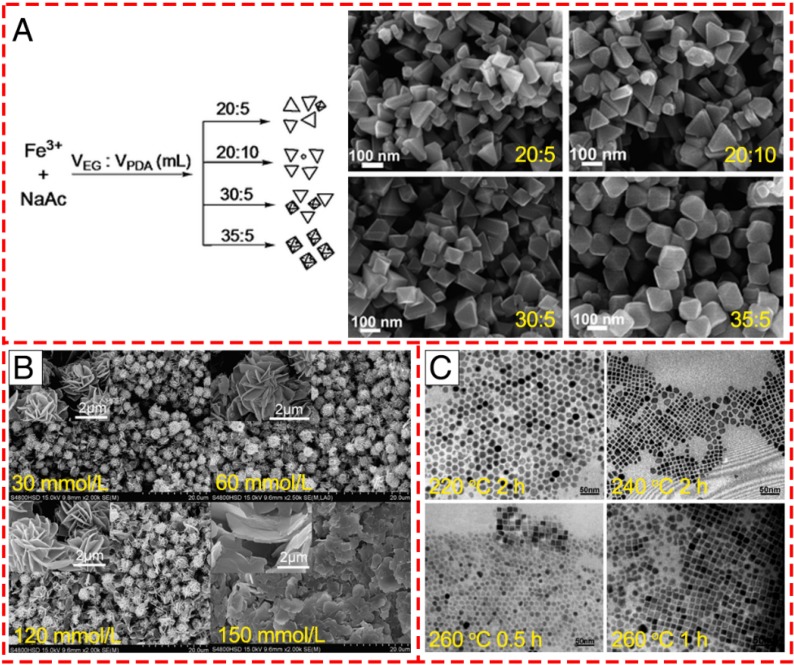

In addition to the above-mentioned synthesis strategies for the production of the IONPs with various morphologies, recently, it has been observed that various morphologies can also be obtained from a single reaction by carefully adjusting the ratio or concentration of the reactants or the reaction parameters, including reaction temperature or time. Zhang et al. found that the amount of sodium acetate (NaAc) and the volume ratio of ethylene glycol (EG) and 1, 3-propanediamine (PDA) played an essential role in the formation of different morphologies of IONPs in their hydrothermal route 41. By keeping other reaction conditions constant, single-crystal IONPs with pseudo-octahedral, irregular or triangular nanoprism structures were obtained using different weights of NaAc in the fabrication (Figure 3A). Furthermore, the rough plate-like morphology transformed into smooth triangular nanoprisms (TNPs) with a few octahedral structures with increasing amount of PDA compared to EG. When the volume ratio of EG:PDA reached 35:5, all the TNPs changed into octahedral structures with a uniform size distribution. Apart from the influence of solvent, it has been revealed that variation of the concentration of the surfactant tetra-n-butylammonium bromide (TBAB) could modulate the microstructure and morphology of flower-like architectures (Figure 3B) 42. With increasing concentration of TBAB from 30 to 150 mM, the flower-like structure consisted of petals with looser packing. When the TBAB concentration was as high as 150 mM, the morphology was composed of only the nanosheet structures, which indicated that TBAB could control the size of the nanosheets that compose the flower-like structures. Furthermore, previous studies revealed that reaction temperature and time were significant in the preparation of Fe3O4 nanocubes 43. As shown in Figure 3C, the shapes of the final products obtained at 220 °C for 2 h were roughly spherical without cubes and arranged in a closely packed array. However, plenty of nanocubes were observed when the temperature was increased to 240 °C. Additionally, prolonging the reaction time from 0.5 to 1 h could increase the number of nanocubes and lead to a more uniform size distribution. These results demonstrated that high temperatures or long reaction times seem to be desirable to get monodisperse Fe3O4 nanocubes.

Figure 3.

Controlled synthesis of different shapes of IONPs via varying the reaction conditions. (A) Varying the solvent component ratio. Reproduced with permission from 41, copyright 2010. (B) Controlling the alkaline reaction environment via different concentration of TBAB. Reproduced with permission from 42, copyright 2011. (C) Controlling the reaction temperature and time. Reproduced with permission from 43, copyright 2010.

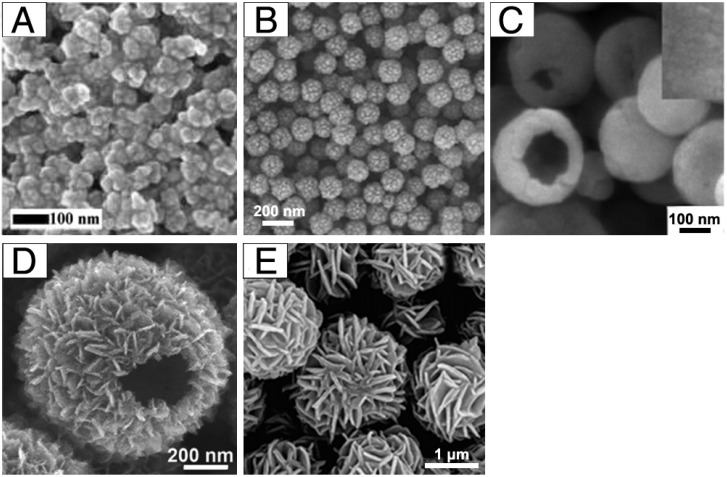

Most of the previous work has focused on the design of IONPs with specific shapes. However, the aggregation state of IONPs, which is defined as an arrangement and organization of single-crystal Fe3O4, also plays an essential role in their applications as theranostic agents. Our previous work described the synthesis of iron oxide clusters (Figure 4A) as a MRI contrast agent via a one-pot hydrothermal method in ethylene glycol/diethylene glycol binary solvent 44. The above synthetic method could be extended to synthesize ferrite nanospheres with sizes from 20 to 300 nm by varying the ethylene glycol/diethylene glycol ratio. Liu et al. prepared monodisperse, hollow and core-shell magnetite (Fe3O4) spheres by a simple one-pot method based on hydrothermal treatment of FeCl3, citrate, polyacrylamide and urea (Figure 4B) 45. The nanoparticle formation undergoes two stages: the formation of amorphous, monodisperse solid spheres and transformation of the solid spheres to hollow spheres or core-shell spheres. As carriers for targeted drug delivery, hierarchical hollow structures are excellent due to their efficient delivery of theranostic agents and magnetic targeting ability. Many methods have been successfully developed for the construction of hierarchical hollow structures (Figure 4C-D) 46, 47. Additionally, well-defined porous Fe3O4 flower-like nanostructures were synthesized by decomposition of iron alkoxide precursors at high temperature under gas protection 42. Moreover, hollow structures of IONPs could themselves act as both drug carrier and therapeutic agent, indicating their attractive potential for magnetic theranostic applications.

Figure 4.

Example morphologies of aggregates of IONPs: (A) clusters, (B) porous core-shell spheres, (C) hollow spheres with a smooth surface, (D) hollow spheres with a rough surface, and (E) nanoflowers. (A) Reproduced with permission from 44, copyright 2017. (B) Reproduced with permission from 45, copyright 2010. (C) Reproduced with permission from 46, copyright 2008. (D) Reproduced with permission from 47, copyright 2015. (E) Reproduced with permission from 42, copyright 2011.

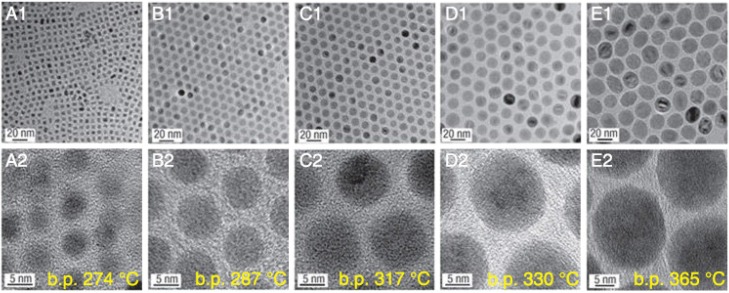

Medical applications of IONPs for MRI and cancer hyperthermia normally require that the nanoparticles are superparamagnetic with a proper size and narrow particle size distribution 48. Therefore, the synthesis of IONPs with controlled size has long been of scientific and clinical interest, and many outstanding research works have been performed. Park et al. reported an ultra-large-scale synthesis method for preparation of monodisperse nanocrystals using inexpensive and non-toxic metal salts as reactants 29. This method could synthesize monodisperse nanoparticles in a single reaction without a size-sorting process and the size of the products could be easily controlled via varying the reaction conditions. As shown in Figure 5, IONPs with sizes of 5, 9, 12, 16 and 22 nm have been synthesized using 1-hexadecene, octyl ether, 1-octadecene, 1-eicosene, and trioctylamine as solvent, respectively. Moreover, the size of the IONPs could be further fine-tuned by changing the concentration of oleic acid. Meanwhile, a general, reproducible and simple strategy for controlling the size, shape, and size distribution of magnetic oxide nanocrystals was introduced by Jana et al. on the pyrolysis of metal fatty acid salts. The size control of IONPs was achieved by varying the concentration and/or the chain length of the fatty acids. It is clear that a higher concentration of ligand will result in larger and nearly monodisperse nanocrystals. Besides the impact of solvent, surfactant, pH, reaction temperature and time, iron source and the precursor also play essential roles in determining the size of as-synthesized nanocrystals. Lida et al. showed that the size of IONPs changed from ~37 nm to ~9 nm by replacing ferrous salt with a mixture of ferrous and ferric salts, revealing that the particle diameter of IONPs mainly depends on the valence of the iron salt instead of the kind of counter ion 49.

Figure 5.

Size-controlled synthesis of IONPs via using various solvents with different boiling points (b.p.). (A1, A2) 5 nm with 1-hexadecene (b.p. 274 °C), (B1, B2) 9 nm with octyl ether (b.p. 287 °C), (C1, C2) 12 nm with 1-octadecene (b.p. 317 °C), (D1, D2) 16 nm with 1-eicosene (b.p. 330 °C), (E1, E2) 22 nm with trioctylamine (b.p. 365 °C). Reproduced with the permission from 29, copyright 200.

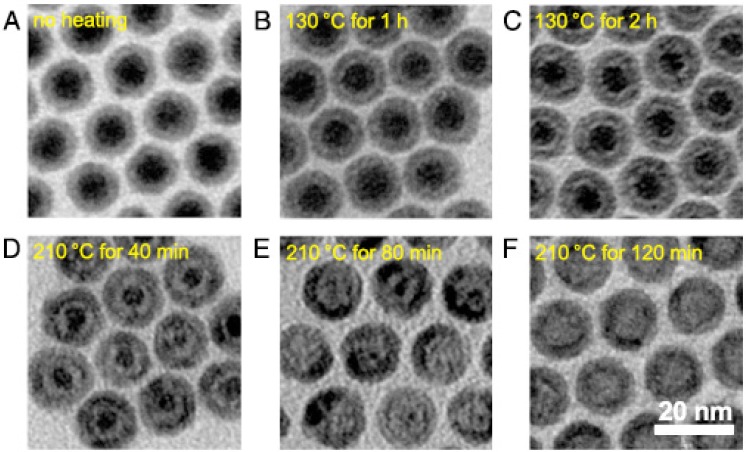

Most of the studies mentioned above have focused on the controlled size of whole particles. Peng and Sun demonstrated thermal decomposition of [Fe(CO)5] in the presence of oleylamine to produce various core-shell-void Fe-Fe3O4 nanoparticles with controllable size based on the nanoscale Kirkendall effect (Figure 6) 50. The as-prepared Fe nanoparticles were not chemically stable, so a core-shell Fe-Fe3O4 structure could be formed when exposed to air. Moreover, further controlled oxidation of these core-shell nanoparticles in the presence of the oxygen-transfer reagent trimethylamine N-oxide leads to the formation of intermediate core-shell-void Fe-Fe3O4, and further to hollow IONPs. Furthermore, by controlling the heating temperature and time, the Fe3O4 shell layer thickness of the core-shell IONPs increased from 2.5 nm in the amorphous seeds to 3.5 nm in the final hollow nanoparticles. Size-controlled synthesis of IONPs is significantly important for its application in the field of magnetic theranostics, especially in applications like MRI, drug delivery, and cancer therapy based on the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, which will be discussed in detail below.

Figure 6.

TEM images of various Fe-Fe3O4 (A) and hollow IONPs (B-E) after heating the seed Fe-Fe3O4 nanoparticles. (B) 130 °C for 1 h, (C)130 °C for 2 h, (D) 210 °C for 40 min, (E) 210 °C for 80 min, (F) 210 °C for 120 min. Reproduced with permission from 50, copyright 2007.

Biocompatibility of IONPs

In recent years, IONPs have been widely applied in theranostic areas, including drug delivery 51, 52, separation and tracking of cells 53, 54, cell labeling 55, 56, cancer imaging 57-59, and hyperthermia for cancer therapy 60-62. The prerequisite of their theranostic application is good biocompatibility and safety. Although it is generally considered that IONPs are biocompatible compared with other metal oxide nanoparticles, there still remains controversy on this issue. Various reports revealed that there are close links between biocompatibility or toxicity and size, concentration, surface properties, shapes and structures of nanoparticles 63, 64. Numerous works have been carried out on the biocompatibility of IONPs for magnetic theranostics including in vitro and in vivo investigations 11, 16, 65. Here, we review recent studies of IONPs biocompatibility related to various factors including shape, size, surface properties, and structure.

Effect of shape

As mentioned above, as the physiochemical properties of IONPs strongly depend on their morphology, a lot of work has been completed on synthesizing IONPs with different shapes, such as nanooctahedrons, nanorods, nanocubes, nanohexagons, nanowires, nanotubes, nanoplates, nanoflowers, nanorings and nanocapsules. An in vitro biocompatibility study was carried out on IONPs with different morphologies including nanooctahedrons, nanorods and nanocubes in human A549 lung tumor cells 66. IONPs were evaluated at concentrations in the range of 10-1000 μg mL-1. After 24 h incubation, the CCK-8 assay results revealed that more than 90% of cells survived, which suggested that these nanoparticles were quite safe to the cells within the tested concentration range. Spherical, hexagonal and wire-like shaped IONPs that were coated with carboxyl-terminated poly(ethylene glycol)-phospholipid (DSPE-PEG) for enhanced dispersion in water were tested in ECA-109 cells and the results showed that such nanoparticles were uptaken by cancer cells, and the particles induced negligible toxicity to the cells without laser irradiation. Upon laser irradiation, the cell structures were seriously damaged by the photothermal effects induced by the nanoparticles 67. The cytotoxicity of magnetite nanorings (NRs) with high luminescence and a magnetic vortex core capped with quantum dots (QDs) was tested on normal human lung fibroblast cells (NHLF), MGH bladder cancer cells, and SKBR3 breast cancer cells. The results of a viability assay showed that after 24 h incubation with QD-FVIOs (ferrimagnetic vortex-state iron oxide nanorings) at 37 °C, both QD-FVIO1 (~1.8×102 QDs per NR) and QD-FVIO2 (~3.6×102 QD per NR) showed insignificant toxicity at low Fe3O4 concentration (50 μg mL-1) for all cells 68. Concentration is a key factor for cell viability when co-incubated with IONPS, and in order to reveal the biocompatibility of IONPs at different concentrations, Ankamwar et al. 63 explored cytotoxicity tests as a function of concentration from low (0.1 μg mL-1) to high concentration (100 μg mL-1) using various human glial, breast cancer and normal cell lines. The results showed that IONPs in the concentration range of 0.1-10 μg mL-1 exhibited almost nontoxicity towards human glial (D54MG, G9T, SF126, U87, U251, U373), breast cancer (MB157, SKBR3, T47D) and normal (H184B5F5/M10, WI-38, SVGp12) cell lines, which revealed the biocompatibility of IONPs, while mentionable cytotoxicity could be noticed at 100 μg mL-1. In summary, most of IONPs show excellent biocompatibility without any significant cytotoxicity when the concentration is less than 100 μg mL-1. Higher concentrations (>100 μg mL-1) could result in noticeable cytotoxicity, which is dependent on the cell line.

Effect of size

Size of the IONPs is also significant factor for nanoparticles when applied in biomedicine. In order to avoid prompt spleen and liver filtration and prolong the blood circulation time, the size of nanoparticles should be small (<200 nm). Meanwhile, in order to evade rapid kidney filtration, the size should be >10 nm 69-71. Here, we collected biocompatibility information about IONPs within this size range.

In a recent study, the relative viability of the fibroblast cell line L929 incubated with IONPs (~14 nm) prepared by a traditional co-precipitation method under the action of a rotating magnetic field (RMF) was tested 72. When the concentration of IONPs was 6.25 ug mL-1, the viability of the cells measured by WST-1 (2-(4-iodophenyl)-3-(4-nitrophenyl)-5-(2,4-disulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazalium) Cell Proliferation Assay was reduced to 90%. When the IONPs concentration reached 100 ug mL-1, the highest mitochondrial activity was observed. Meanwhile, Shuodo et al. reported that even with higher concentrations between 125 and 1000 ug mL-1, the cell viability did not decrease 73. This may be explained by the low uptake of these nanoparticles by the cells. In another study 74 IONPs with sizes around 10-20 nm were tested for their compatibility with fibroblasts (L929) and cancer cells (HeLa). An SRB assay showed that after 24 h incubation with bare magnetic nanoparticles at a concentration of 0.015 mg mL-1, more than 90% of primary fibroblasts (L929) and cancer cells (HeLa) were viable. The result suggests that these samples are biocompatible and do not have an obvious toxic effect and so can be used in vivo. Urbas et al. 75 demonstrated that when the IONP size was ~100 nm, WST-1 and LDH cytotoxicity assays of IONP-exposed L929 cells revealed that IONP nanospheres affect cell metabolism. However, the cells incubated with IONPs exposed to RMF presented relatively higher cellular activity. It was noticed that only 10.06 mT of RMF influenced cell response in a dose-dependent manner. Also, a LDH leakage assay showed that the highest cytotoxicity effect of IONPs with RMF was at an IONP concentration of 100 ug mL-1 for all tested values of RMF intensity.

Besides the cytotoxicity of IONPs, much interest has been focused on their biodistribution in vivo. Bourrinet et al. compared the biodistribution of ferumoxtran (also known as Combidex® or Sinerem™), a 30 nm HD dextran-coated IONP, with the previously reported biodistribution of 80 nm ferumoxides 76. In rats, ferumoxtran particles mainly localized in the spleen (37-46% ID) and lymph nodes (5-11% ID) 24 h after intravenous injection and had modest distribution to the liver (25% ID), while there was predominant liver uptake of the larger ferumoxides (83% ID at 1 h postinjection and >50% ID after 24 h) 77. Papisov et al. studied dextran-coated IONPs with an overall size of ~21 nm and found that these smaller IONPs also heavily concentrated in the lymph nodes (2-50% ID/g tissue for each of three tested lymph node groups) and spleen (15-20% ID/g tissue) of rats, and displayed a circulation half-life similar to that of the 30 nm ferumoxtran NPs 78.

Effect of structure

The structure of IONPs represents the shape, size and spatial distribution of mineral aggregations. There are some studies about how to obtain IONPs with different structures including aggregates, mesopores, magnetic micro needles, clusters and hollow microspheres. The cytotoxicity of IONPs aggregates (1.75 mg mL-1 magnetite equivalent) with different hydrodynamic sizes including 1000 nm (1003 ± 90 nm), 750 nm (748 ± 44 nm), 405 nm (406 ± 17 nm), 345 nm (344 ± 8 nm) and 220 nm (221 ± 2 nm) was studied using A549 cells 79. Below 400 nm, about 80% of cells survived and the results also suggested that the cytotoxic effect evolves into a necrotic mechanism around 400 nm. Cytotoxicity tests of HepG2 and MDCK cells incubated with mesoporous IONPs with good water dispersity showed that cell viability was not adversely affected (80-90%) at concentrations up to 40 ug mL-1 80. Meanwhile, Kavaldzhiev et al. reported that IONP microneedles did not compromise HCT116 cell viability. Yang et al. reported the biocompatibility of Fe3O4 hollow microspheres in Hela cells. When the cells were incubated with the particles at concentrations of 20 to 100 ug mL-1 for 24 h, the cell viability remained above 90%. So, these results clearly indicate that magnetite particles with different structures have low cytotoxicity under controlled concentration 81, 82.

Effect of surface properties

IONPs designed with a neutral surface charge are most likely to exhibit longer circulation and reduced uptake by the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS) due to decreased opsonization 83. Positively or negatively charged IONPs normally show increased liver uptake and shorter circulation times as compared with neutrally charged ones 84. Naked IONPs usually show higher toxicity both in vitro and in vivo, so the surface modification of prepared IONPs is a common and essential strategy for clinical applications. Surface modification may have many important functions including (1) to protect against iron oxide core agglomeration and improve dispersion, (2) to provide chemical handles for the conjugation of drug molecules, targeting ligands, and reporter moieties and (3) to limit non-specific cell interactions for lower cytotoxicity and higher biocompatibility 85. The most commonly used biocompatible coating materials are polymers, inorganic materials, liposomes and proteins 86-88. Except for possessing ideal biocompatibility, the ideal coating materials for IONPs modification should have a high affinity to IONPs and not stimulate the immune system or be antigenic 24.

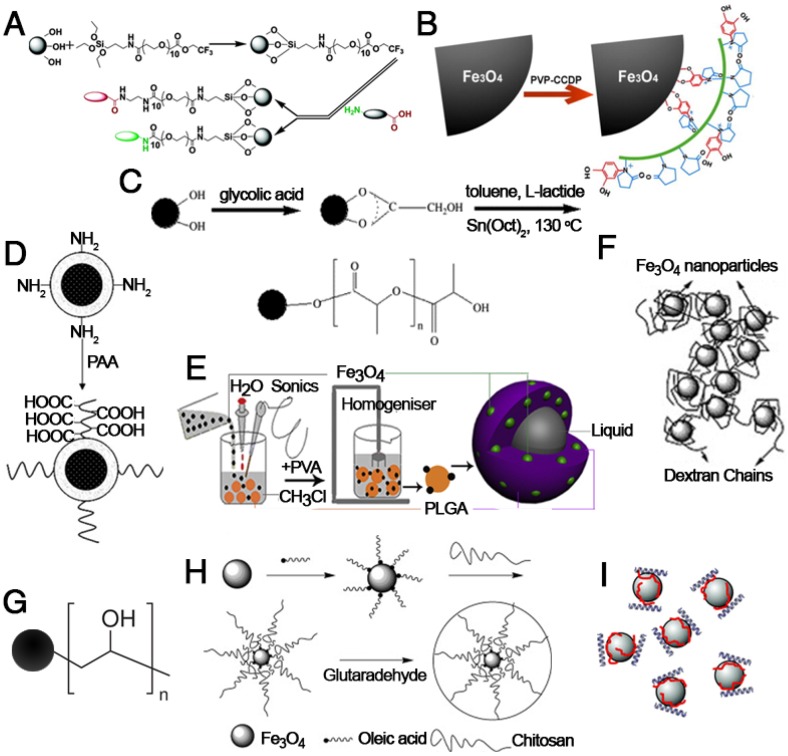

Polymer-functionalized IONPs have been extensively investigated due to their advantages of unique physical and chemical properties, significantly decreased toxicity, increased repulsive forces to balance the magnetic and Van der Waals attractive forces, and easy functionalization 24. Figure 7 shows the basic structure of IONPs modified with various natural or artificial polymers. Among them, polyethylene glycol (PEG), which has been approved by the FDA, is widely used as a coating material for IONPs due to its excellent biocompatibility and can be eliminated from the body by either the kidney (for PEGs < 30 kDa) or digestive system (for PEGs > 20 kDa) 98. Moreover, the strong attachment of PEG molecules on the surface of IONPs can also prolong the circulation time in blood and reduce MPS uptake. For example, a functional PEG saline allows covalent immobilization of PEG to the IONP surface to increase the particle circulation time in blood and particulate dispersion. In addition, this new monolayer of PEG saline enables targeted uptake of nanoparticles into tumor cells in vivo 89. Besides PEG, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), polyethylenimine (PEI), polyacrylic acid (PAA), poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA), dextran and protein molecules are widely used to stabilize nanoparticles, prevent their agglomeration in solvent, and increase their biocompatibility 97, 99-106. The surface modification of IONPs with polymers further provides a strategy to realize multifunctional applications in magnetic theranostics. Ge et al. prepared IONPs coated with a modified chitosan with a covalently attached fluorescent dye 107. The prepared FITC-labeled particles proved to be biocompatible and possessed theranostic properties for nanomedicine applications. However, the in vivo aggregation and poor colloidal stability of the polymer-encapsulated IONPs might be the major concern for clinical applications.

Figure 7.

Modification of IONPs with (A) poly(ethylene glycol) saline, (B) poly(vinyl pyrrolidone)-catechol, (C) polylactice acid, (D) polyacrylic acid, (E) poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid), (F) dextran, (G) polyvinyl alcohol, (H) chitosan and (I) polyethyleneimine. (A) Reproduced with permission from 89, copyright 2004. (B) Reproduced with permission from 90, copyright 2013. (C) Reproduced with permission from 91, copyright 2008. (D) Reproduced with permission from 92, copyright 2009. (E) Reproduced with permission from 93, copyright 2012. (F) Reproduced with permission from 94, copyright 2008. (G) Reproduced with permission from 95, copyright 2008. (H) Reproduced with permission from 96, copyright 2010. (I) Reproduced with permission from 97, copyright 2007.

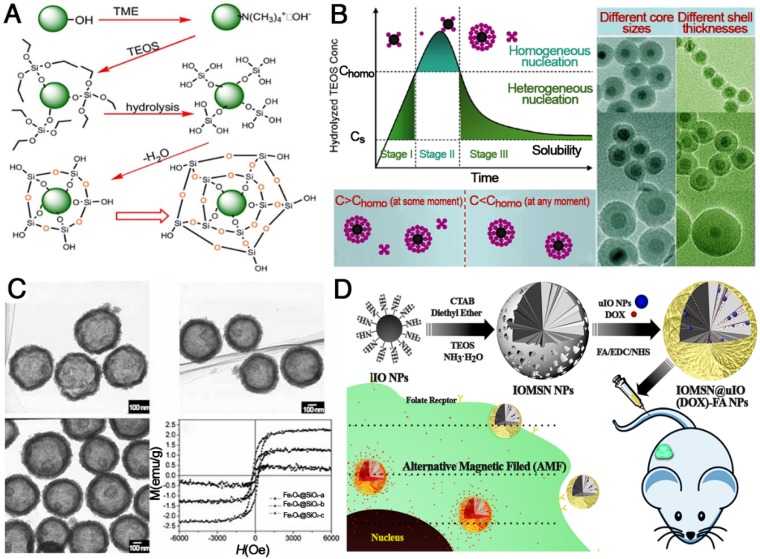

IONPs coated with either liposomes or silicon dioxide have important advantages including (1) a simple and easy modification procedure, (2) feasibility to encapsulate therapeutic or imaging agents within the coating layers, and (3) protection of pharmaceuticals from the body until degradation in target cells 108-112. In recent years, various Fe3O4@SiO2 core-shell structures have been successfully developed in the field of theranostics (Figure 8). The formation of Fe3O4@SiO2 core-shell structures usually consists of synthesis of IONPs, deposition of SiO2 via hydrolysis of tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS), condensation of silicate and final crystallization of the colloidal silica (Figure 8A). For example, Fe3O4@SiO2 with different thickness of SiO2 were successfully obtained and the silica shell thickness varied from 3 nm to 13 nm with TEOS/Fe3O4 ratios increasing from 4/3 to 2/1 μL mg-1. For Fe3O4@SiO2-PEG nanoparticles, even the highest concentration (about 200 μg mL-1) had no significant influence on the survival of mNSCs mouse stem cells 113. Besides mesoporous silica, liposome coating is another excellent strategy to decrease the cytotoxicity of IONPs. A previous study revealed the in vitro biocompatibility of magnetic liposomes 114 , and the results showed that the viability of L929 cells was more than 90% for an extract concentration of 5 mg mL-1. At an extract concentration 5 mg mL-1, cell viability was 94.2±1.3% even after 48 h of incubation. Therefore, increased biocompatibility of nanoparticles by surface modification with liposomes was clearly demonstrated within an appropriate concentration range 115. As is well-known, results from in vitro cytotoxicity assays are different from those of in vivo biocompatibility tests due to the influence of blood, protein, cytoplasm, etc. However, in vitro cytotoxicity is basic and important data to support and guide in vivo studies.

Figure 8.

Functionalization of IONPs with silica. (A) General procedures for coating silica on IONPs. Reprinted with permission from 116, copyright 2006. (B) La Mer-like diagram: hydrolyzed TEOS (monomers) concentration against time for homogeneous nucleation and heterogeneous nucleation and TEM images of different Fe3O4@SiO2 NPs. Reprinted with permission from 117, copyright 2012. (C) TEM images and magnetization curves of Fe3O4@SiO2 hollow mesoporous spheres with varying Fe3O4 content. Reprinted with permission from 118, copyright 2010. (D) Schematic illustration of the preparation of IOMSN@uIO(DOX)-FA NPs and its application as a MRI-guided stimuli-responsive theranostic platform for effective targeted chemotherapy of cancer. Reprinted with permission from 119, copyright 2018.

Magnetic theranostic applications

Advances in nanotechnology have permitted new possibilities for theranostics, which is defined as the combination of therapy and imaging within a single platform 120. Multifunctional nanoparticles enable multimodal imaging with combination of two or more imaging modalities or theranostics for simultaneous imaging and therapy. These techniques are expected to overcome the hurdles of traditional diagnosis and therapy through optimized therapy called “personalized medicine”. Among these nanoparticles, IONPs exhibit not only unique material properties but also an integrated design capacity for cell targeting, imaging, and therapy because of their biocompatibility and capacity to enhance proton relaxation under an external magnetic field 121. This combination of properties makes IONPs an ideal platform for theranostics 122. Here, we provide an overview of the existing knowledge and current process of engineering IONPs for cancer theranostics.

Magnetic resonance imaging

MRI is a powerful, noninvasive, clinical molecular and cellular imaging technique, in which the source of the MRI signal comes from nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) signals that are emitted from protons within the human body. Compared with other clinical imaging modalities, it has several advantages including excellent anatomic detail, enhanced soft tissue contrast, and high spatial resolution. Thus, MRI has been a preferred tool for imaging lesions in soft tissue, such as the brain, central nervous system, heart and tumors. However, MRI diagnosis may not be totally exact in some clinical situations, as the relaxation times of normal tissues and lesions often show only small differences and limited contrast. MRI contrast agents can significantly improve the MRI performance through enhancing the MR signal of water protons in surrounding tissues. Though they do not generate signal themselves, the contrast agents can affect the proton relaxation rate so as to improve the MR signals.

Several classes of IONPs have already been approved by the US FDA and European Medicines Agency (EMA) for various MRI contrast agents in clinical applications 123. Compared with commercial gadolinium-based agents, IONPs possess a unique advantage of better biocompatibility, as iron is an essential element in the human body. IONPs also exhibit greater sensitivity at micromolar or nanomolar concentrations than gadolinium complexes, providing an ideal nanoplatform for enhancing the sensitivity and accuracy of MRI. Therefore, IONPs-based contrast agents have received more and more attention 124-126. Based on the relaxation processes, MRI contrast agents can be summarized as positive contrast agents (or T1 contrast agents) and negative contrast agents (or T2 contrast agents). Usually, IONPs larger than 10 nm can be used as negative contrast agents, and recently emerged extremely small magnetic IONPs (ES-MIONs) smaller than 5 nm are potential positive contrast agents 127, 128.

T2 contrast agents

Since their first application as MRI contrast agents 20 years ago, IONPs are usually used as T2 contrast agents due to their predominant T2 relaxation effects. Moreover, their high magnetization values could cause microscopic field inhomogeneity, activate the dephasing of protons, shorten T2 relaxation times of neighboring regions, and decrease the signal intensity in T2-weighted MR images. The ability of IONPs to increase the proton relaxation rates of the surrounding water proton spins is described by the relaxivity rate (r2, or 1/T2). In a rough approximation, r can be related to the square of the saturation magnetization (MS) of the NPs, which is a function of particle size and composition. In addition, experimental variables such as field intensity, environmental temperature, and medium also determine the relaxation times. Although sometimes confused with other endogenous conditions that appear dark in MR images, T2 contrast agents are advantageous because of their exceptionally strong contrast enhancement effects 129, 130.

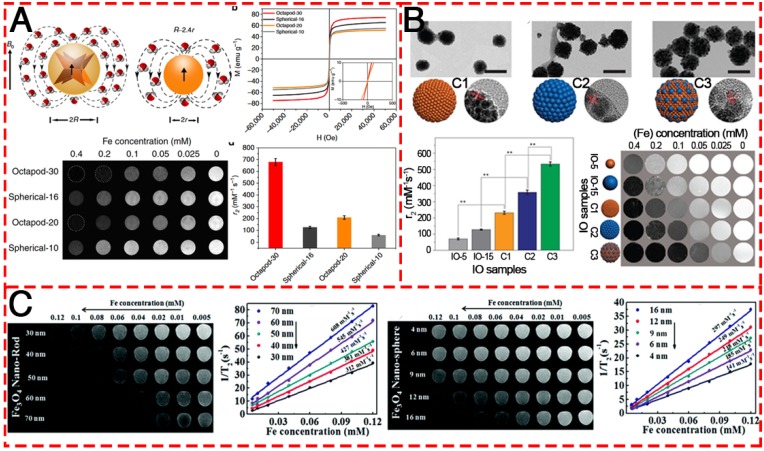

Recently, a great amount of attention has been focused on the optimization of MRI performance by the application of IONPs. Hyeon et al. reported water-dispersible 22 nm cubic IONPs with an extremely high r2 relaxivity at 761 mM-1 s-1, which yielded a superior in vivo MR image of tumors 131. This is the first report on the preparation of dispersible single-core IONPs in the static dephasing regime (SDR). It has normally been assumed that the r2 values of magnetic nanoparticles would increase with increasing size. However, their work demonstrated that large aggregates of IONPs generate a very strong magnetic field, as the nearby water protons are completely dephased and unable to contribute to the MR signal. Based on this result, much attention has been paid to the relationship between the morphology of IONPs and the MRI performance. A kind of Octapod IONPs (Figure 9A) with an edge length of 30 nm was synthesized and exhibited an ultra-high r2 relaxivity value (679.3 ± 30 mM-1 s-1) as compared to their spherical counterpart of similar material volume 32. Rod-like IONPs with a length of 30-70 nm and diameter of 4-12 nm have also been evaluated (Figure 9C) 132. The shape anisotropy could induce very strong localized magnetic field inhomogeneity and the increased surface area could allow a greater number of hydrogen nuclei of water to be disturbed by the dipolar field of the IONPs, resulting in the higher r2 relaxivity. They found that the relaxation coefficient (r2) gradually increased from 312 to 608 mM-1 s-1 with an increase in the length of NRs. Apart from the effect of morphology, most recently, Chen and co-authors contributed to the understanding of how magnetization influences T2 contrast efficiency in magnetic clusters (Figure 9B). By adopting both experimental investigation and theoretical simulations, they confirmed that the clustering of MNPs enhances local field inhomogeneity, which can be regarded as the major cause of T2 relaxation enhancement in IONP clusters 133.

Figure 9.

T2-weighted contrast MR images of various IONPs. (A) Schematic illustration of the ball models of octapod and spherical IONPs with the same geometric volume, smooth M-H curves, T2-weighted MR images, and comparison of r2 values of IONPs with different diameters: Octapod-30 (~58 nm), Octapod-20 (~49 nm), Spherical-16 (~30 nm) and Spherical-10 (22 nm). Reproduced with permission from 32, copyright 2013. (B) TEM images, r2 values and T2-weighted MR images of different IO clusters C1-C3 (C1: ~115.5nm; C2: ~127.8 nm; C3: ~129.2 nm), as well as the single IO-5 (~5.2 nm) and IO-15 (~15.1 nm) NPs. Reproduced with permission from 133, copyright 2017. (C) The MR contrast effect of Fe3O4 NRs of different lengths and NPs of different diameters. Reproduced with permission from 132, copyright 2015.

In clinical practice, there are five types of superparamagnetic IONPs to use as T2 contrast agent, Ferumoxides (Feridex®), Ferucarbotran (Resovist®), Ferumoxtran-10 (AMI-227 or Code-7227, Combidex®), NC100150 (Clariscan®) and VSOP C184. However, at this time, Resovist® is currently available in only a few countries, including USA and Japan. Other commercialized IONPs-based negative contrast agents have been removed from the market. The probable reasons are summarized: (1) they are negative imaging agents, for which the resulting dark signal could be confused with other pathogenic conditions, including hemorrhage, calcification, and metal deposits; (2) the high magnetic moments of the negative contrast agents can cause susceptibility artifact, distort the magnetic field of neighboring normal tissues or background and generate obscure images with demolished background around the lesions; (3) the relatively large particle sizes of the MIONs used for the T2-weighted contrast agents (usually 60-180 nm) result in a slow clearance, which may cause long-term side effects; (4) the process time of T2-weighted MR imaging is much longer than that of T1-weighted MR imaging.

T1 contrast agents

Contrasting with T2 contrast agents, the major advantage of T1 contrast agents is positive imaging by signal enhancement, which can maximize the forte of MRI, that is, anatomic imaging with high spatial resolution. Furthermore, their bright signal can be distinguished clearly from other pathogenic or biological conditions. As T1 contrast agents are basically paramagnetic, they do not disrupt magnetic homogeneity over large distances. T1 relaxation is the process of equilibration of the net magnetization (Mz) after the introduction of an RF pulse. This change of Mz is a consequence of energy transfer between the proton spin system and the nearby matrix of molecules. The presence of T1 contrast agents near the tissue enhances its relaxation and shortens the T1 relaxation time. In particular, metal ions with a large number of unpaired electrons such as Gd3+, Mn2+, and Fe3+ and so on have a very effective relaxation effect. IONPs have also been studied as T1 contrast agents, but their high magnetization values have limited their use in T1 imaging because of their excessively high r2 values. Recent advances in this field have revealed that ES-MIONs with sizes smaller than 5 nm can exhibit remarkable T1 MRI enhancement due to the surface-spins from these small NPs.

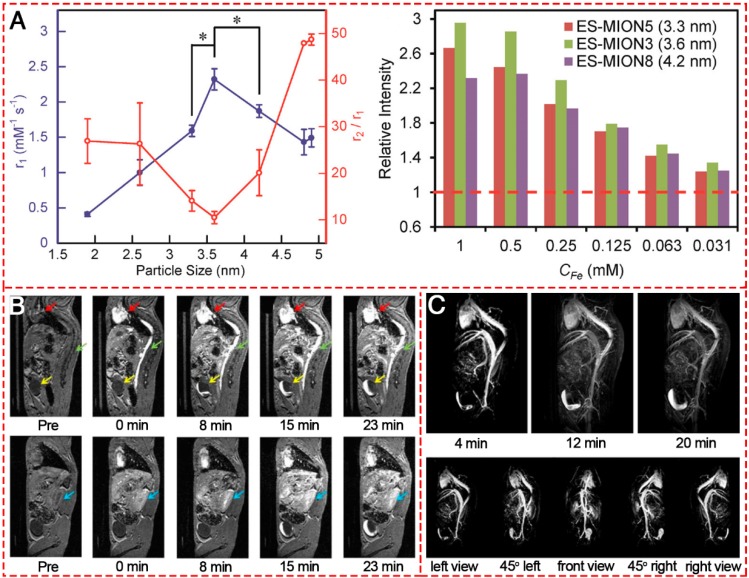

ES-MIONs as T1-shortening blood pool contrast media was first explored in 2000 134. The IONPs have a core diameter of 4 nm and a hydrodynamic diameter of 7.0±0.15 nm and have a suppressed magnetization, which is proportional to r2 relaxivity, resulting in an increased r1 relaxivity ranging from 2 to 50 mM-1 s-1 and a decreased ratio of r2/r1 to less than 4. The T1 relaxivity of the iron oxide-based blood pool contrast medium (VSOP-C184) was a factor of 4-5 higher than that of commercial MAGNEVIST® and was applied at a dose corresponding to about 1/4 to 1/5 of the dose of MAGNEVIST®. Thereafter, many researchers showed great interest in exploring IONPs-based T1-weighted MRI contrast agents. The MR contrast effect of ES-MIONs with seven different sizes below 5 nm (i.e., 1.9, 2.6, 3.3, 3.6, 4.2, 4.8, 4.9 nm) were developed and explored on a 7T MRI scanner 18. The results (Figure 10A) indicated that upon increasing the particle size from 1.9 to 3.6 nm, the r1 value increased. However, the r1 value decreased with further size increase from 3.6 to 4.9 nm. Thus 3.6 nm could be the optimal particle size for ES-MIONs as T1-weighted MR contrast agents. Wei et al. developed zwitterion-coated exceedingly small superparamagnetic IONPs (ZES-SPIONs) consisting of ∼3 nm inorganic cores and a 1 nm ultrathin hydrophilic shell 135. The ZES-SPIONs had renal clearance and showed minimal nonspecific interactions. They had a low r2/r1 relaxivity ratio of 2 at 7 T. Due to their strong T1 contrast and long circulation time, the blood vessels in this magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) study could be imaged with a spatial resolution of ∼0.2 mm (Figure 10B-C). Renal clearance and biodistribution results further demonstrated that ZES-SPIONs are qualitatively different from previously reported SPIONs. This work may open up opportunities to develop ES-MIONs that show effective T1 contrast as Gd-free alternatives to Gd-based contrast agents.

Figure 10.

T1-weighted MR images of different IONPs. (A) r1 value and r2/r1 ratio of ES-MIONs as a function of particle size.. (B) T1-weighted MR images of a mouse injected with ZDS-coated exceedingly small SPIONs (ZES-SPIONs) at 7 T. (C) T1-weighted MRA of a mouse injected with ZES-SPIONs at 7 T. (A, B) Reproduced with permission from 18, copyright 2017. (C) Reproduced with permission from 135, copyright 2017.

The future challenges and opportunities in the application of ES-MOINs as T1 imaging agents are summarized: (1) further efforts are still needed to enhance the r1 value via improving the magnetism, particle size, water dispersity, and/or morphology; (2) proper surface modifications should be made to prolong the circulation time for a better contrast effect and reduced side effects; (3) various targeting strategies (active targeting, Trojan-horse targeting 136) can be used to enhance the tumor specificity; (4) multimodality imaging agents or theranostic agents based on IONPs should be further explored.

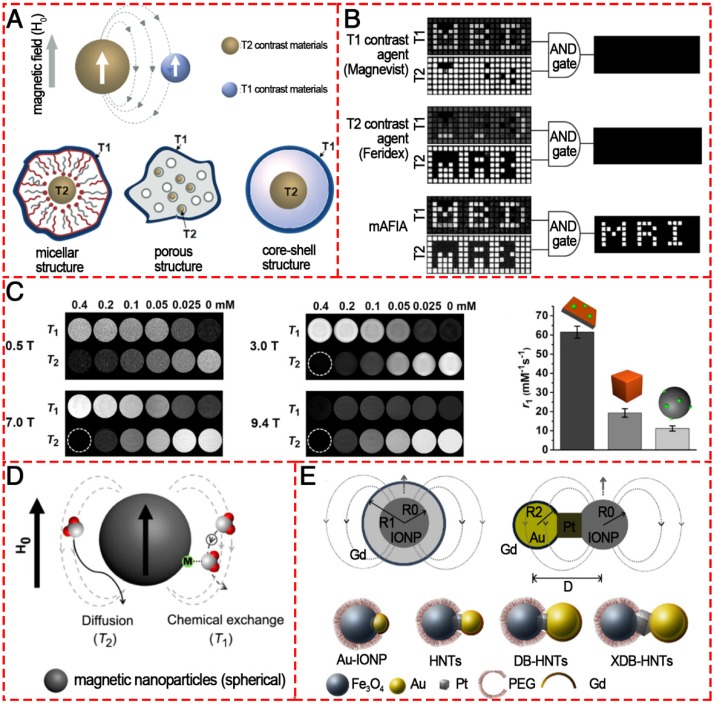

T1/T2 dual-mode contrast agents

Conventional MRI contrast agents typically only provide single-mode enhancement, generating either bright (T1) or dark (T2) signal enhancement. Usually, it is hard to interpret the MR images because endogenous artifacts such as fat, hemorrhages, calcification, blood clots, and air are commonly found in disease lesions, which confuse the MR signals originating from the tissues. To overcome such ambiguities and accurately interpret the MR images, simultaneous acquisitions of positive and negative contrasts have been extensively pursued to improve the ability to diagnose disease, guide therapy, and predict outcomes. The T1/T2 dual-modal strategy for MRI has attracted considerable interest because it can give highly accurate diagnostic information by the beneficial contrast effects in both T1 imaging with high tissue resolution and T2 imaging with high feasibility of detection (Figure 11). There are no discrepancies in the penetration depth between T1 and T2 images and no image mismatch issues. In many cases, both T1 and T2 MR images can be obtained to cross-validate possible false positive.

Figure 11.

Various T1/T2 dual-modal MRI contrast agents based on IONPs. (A) Magnetic coupling between T1 and T2 contrast materials and the structures for a dual-modal nanoparticle contrast agent. Reproduced with permission from 137, copyright 2010. (B) T1 and T2 images of phantoms were post processed using the AND logic algorithm. Reproduced with permission from 138, copyright 2014. (C) T1- and T2-weighted phantom imaging of GdIOPs (Gd2O3-embedded iron oxide nanoplates) under four different magnetic fields (0.5, 3.0, 7.0, and 9.4 T) and a comparison of r1 values of GdIOPs, IO cubes, and GdIO spheres in 0.5 T. Reproduced with permission from 140, copyright 2015. (D) Phenomenon of proton interaction with a spherical magnetic nanoparticle system: molecular water diffusion and chemical exchange with surface magnetic metals are related to their T2 and T1 contrast enhancements, respectively. Reproduced with permission from 139, copyright 2014. (E) Engineering heterogeneous nanostructures for magnetic coupling of T1 and T2 contrast agents with (left) core/shell structures or (right) dumbbell structures and the design of dumbbell heterostructures for dual T1- and T2-weighted MRI. Reproduced with permission from 142, copyright 2014.

For the purpose of dual-modal enhancement, a “magnetically decoupled” core-shell structure was proposed 137. By inserting a thickness-tunable separating SiO2 layer with a 16 nm SiO2 coating, the dual-modal NP contrast agent had a high r1 of 33.1 mM-1 s-1 and a high r2 of 274 mM-1 s-1. Dual-mode contrast agents significantly improve the accuracy of MRI interpretation because they show bright MR signals in positive T1 mode and dark signals in negative T2 mode. Therefore, only dual-mode contrast agent allows filtration of false error in MRI by an “AND logic” algorithm (Figure 11B). In 2014, Cheon and colleagues developed a dual-mode artifact filtering nanoparticle imaging agent (AFIA) that displayed 2-fold higher T1 and T2 relaxivity coefficients via combining paramagnetic and superparamagnetic nanomaterials compared to the alone paramagnetic nanomaterials or superparamagnetic nanomaterials 138. This AFIA also had the ability to not only produce high contrast in in vivo imaging but also remove MR artifacts to more accurately diagnose disease. Although various T1/T2 dual-modal strategies have been demonstrated to be reliable, ES-MOINs cannot output high-level diagnostic information about vascular details in MRA due to the relatively low T1 contrast ability and intrinsic T2 interference. To overcome the interference, Gao et al. reported freestanding superparamagnetic magnetite nanoplates (Figure 11C), which have significant T1 and T2 contrast effects 139, 140. While the strong T1 contrast effect can be attributed to the Feoct2-tet1-terminated Fe3O4(111) surface on the two planes that can greatly increase the interactions between surface paramagnetic metal ions and water protons in their vicinity, the T2 contrast effect due to the intrinsically high magnetic moment with unique morphology could provide a strong local field inhomogeneity. Recently, Peng et al. designed and prepared a series of Fe3O4 hybrid nanoparticles with functionalized mesoporous silica shell (Fe3O4@MnO/mSiO2-CD133); the hybrid NPs had different core sizes (3.7, 8 and 17.5 nm), which could tune the induced magnetic field 141. The 17.5 nm large IONPs core induced a magnetic field outside the particle that was strong enough to generate a comparable local field inhomogeneity for the T2 signal and efficiently quench the T1 signal (Figure 11D). Meanwhile, the smaller IONPs core (3.7 nm) had an “inverted MR phenomenon” from T2 contrast agent (CA) to T1 CA due to the intrinsic low magnetization. The 8 nm IONPs core with controlled magnetization was thus the best candidate for safe dual-imaging for living ependymal brain cells of rodents with no local damage under a strong MRI magnetic field. The above-mentioned core/shell structures can provide a feasible way to reduce the interference between T1 and T2 contrast agents when integrated together; however, the T2 contrast effect would be compromised by the shell structure. Fortunately, a dumbbell-like or so-called “Janus” structure (Figure 11E) was established to combine both T1 and T2 contrast agents together, fusing IONP, Pt, and gold nanocrystals via solid-state interfaces 142. Furthermore, the distance between T1 and T2 species could be controlled to reduce magnetic coupling and synergistically enhance both T1/T2 contrast effects. This strategy opens up a new way to design molecular nanoprobes for MRI with excellent accuracy.

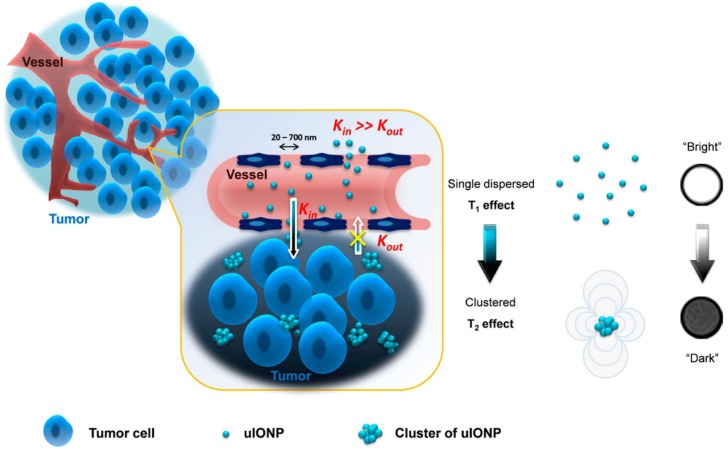

In addition to the dual-modal contrast agents that could simultaneously achieve both positive and negative signal enhancement, most recently, some novel kinds of T1/T2 switching contrast agents have been developed. In 2017, Wang et al. reported ES-MIONs with a 3.5 nm core size and size-dependent bright-to-dark (or T1/T2) MRI contrast switch, which, due to its small size, could easily extravasate through tumor vessels and subsequently penetrate deep into tumors (Figure 12) 143. More importantly, this ES-MIONs could self-assemble or form clusters in the tumor interstitial space to prevent the nanoparticles from re-entering into the circulation via blood and lymphatic vessels, thus improving passive tumor targeting and drug delivery. T1/T2 contrast switching indicated that the ES-MIONs, which were dispersed in the blood with T1 contrast, might self-assemble into larger clusters with T2 contrast after entering the tumor interstitial space. The tissue environment-specific T1 to T2 contrast switch of the ES-MIONs not only enabled anatomic tracking of the delivery of the ES-MIONs, but also reported the tissue characteristics and environment where the nanoparticles accumulate. These innovative breakthroughs provide an effective strategy for the rational design and optimization of engineered theranostics for tumor-targeted imaging and imaging-guided drug delivery.

Figure 12.

Schematic illustration of a mechanism to enhance the EPR effect and tumor accumulation by ultrafine iron oxide nanoparticles (uIONPs) with bright-to-dark T1-T2 MRI contrast switching. uIONPs could extravasate faster and easier from the leaky tumor vessels into a tumor with favorable kinetics and then self-assemble to clusters in the tumor interstitial space with relatively low pH (~6.5), thus restricting clustered uIONPs intravasation back into blood circulation. Reproduced with permission from 143, copyright 2017.

Different imaging technologies possessing various diagnostic resolutions and sensitivities at different levels are often used in combination to achieve complementary accuracy and precision in diagnosis. T1/T2 dual-modal MRI provides paired anatomical images at the same levels but with different contrasts; this imaging technology can produce mutually confirmative information from both the T1 bright and T2 dark pre-contrast and post-contrast images.

Magnetic hyperthermia

The application of hyperthermia (or heat) in the treatment of disease is as old as medicine itself. Indeed, heat was mentioned as a potential treatment of disease more than 5000 years ago, when Hippocrates of Kos, the father of medicine, gave a famous comment on hyperthermia: “those diseases which medicines do not cure, the knife cures; those which the knife cannot cure, fire cures; and those which fire cannot cure, are to be reckoned wholly incurable.” It is believed that the oldest description about the use of hyperthermia is in Edwin Smith's surgical papyrus about the treatment of breast cancer. Today, hyperthermia remains a promising approach for cancer treatment like surgery, chemotherapy, gene therapy, immunotherapy and radiotherapy. Three kinds of heating treatment are currently distinguished: hyperthermia, thermoablation and magnetic hyperthermia (MHT). The main advantage of MHT is related to the ability of magnetic nanoparticles to distribute into small regions to create a temperature differential between the tumor and healthy tissues. Furthermore, its noninvasive property and minimal damage to normal cells have made this method a promising cancer therapy option.

As we know, the main disadvantages of conventional hyperthermia methods are inhomogeneity in the heat distribution profile and lack of thermal distinction between the lesion site and the surrounding normal tissues. Moreover, this inhomogeneity could create unheated regions inside the tumor, allowing it to eventually relapse. Thus, selection of an appropriate means for heat delivery to obtain the highest therapeutic ratio (thermal differentiation between tumor and healthy tissues) is an important and challenging issue in hyperthermia. Based on the working mechanism that heat can be induced by magnetic nanoparticles under alternating magnetic field, magnetic particle hyperthermia (MPH) can achieve local heating only within the tumor site while avoiding the side effect of unwanted heat to the normal tissue nearby. Clinical studies on MPH were started by Maier-Hauff et al., who tested the efficacy of hyperthermia induced by SPION-coated aminosilane for the treatment of glioblastoma multiforme. Recently, the company MagForce reported its NanoTherm® therapy using MNPs and the clinical trial showed that hyperthermia followed by radiotherapy provided a median survival time of 13.4 months in 59 patients with glioblastoma, which is very high compared with 6.2 months survival for patients in the control group 52.

Among all MNPs, IONPs are currently considered the most favorite heating agent for MPH because of their interesting size-dependent magnetic properties, biocompatibility, minimal toxicity, ease of excretion, and ease of functionalization. Furthermore, IONPs with high stability in tumor tissue create the possibility of multifractionated treatment after a single injection. The heating efficiency, characterized by specific absorption rate (SAR) or specific loss power (SLP), of most IONPs reported to date ranges from a few to a few hundred watts per gram. Unfortunately, the poor heating efficiency makes it difficult to reach the desired temperature at a relatively low dose of IONPs, as is the challenging case in most therapeutic applications. Thus, optimizing MPH for high heat induction is critical for developing IONPs heating-based therapeutics.

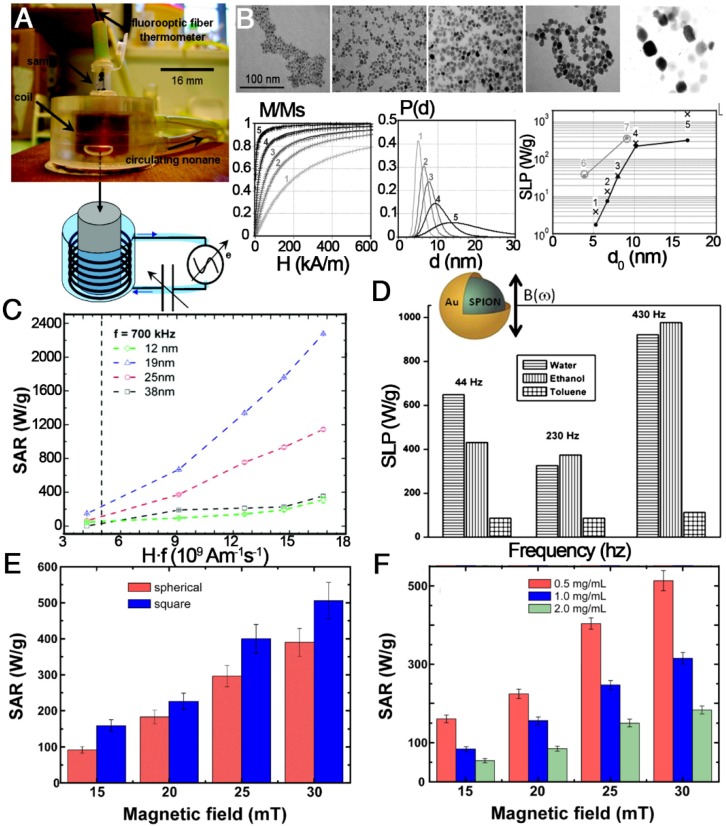

In recent years, much effort has been made to explore the relationship between SAR or SLP value and size, shape, concentration, crystalline anisotropy, intensity and frequency of magnetic field, and degree of aggregation or agglomeration of the nanoparticles (Figure 13) 62, 144-149. In 2009, Gonzales-Weimuller et al. synthesized a series of high-quality IONPs of tailorable size from 5 to 15 nm through the thermal decomposition method 147. The SLP of the 5 to 14 nm IONPs increased from 180 to 447 W g-1 under H = 24.5 kA m-1 and f = 400 kHz. However, the SLP did not always increase with increasing size, and the optimal size should be near the transition from superparamagnetic to ferri/ferromagnetic. This size-dependent heating effect is in agreement with earlier theoretical predictions. In 2012, Guardia et al. prepared a series of cube-shaped IONCs with cube edge lengths of 12, 19, 25, and 38 nm by a one-pot synthesis method 61. The 19 nm IONCs were found to reach a SAR value of 2277 W gFe-1 at 24 kA m-1 and 1000 W g-1 at 22 kA m-1, which was over 10 times and 2 times higher than that from the 12 and 24 nm NPs, respectively. In the linear response theory model, 22 nm spherical nanoparticles with low effective anisotropy (around 5×104 erg cm-3) present the best heating properties. The size and anisotropy of nanocubes of 19 nm, and to a lesser extent of 22 nm, are both in the favorable range to have high SAR values 62. Besides the influence of size and shape, theoretical modeling suggested that the SLP of superparamagnetic NPs could be optimized when the K was in the range from 0.5×104 to 4.0×104 J m-1, but the Ms should also be considered to maximize the SLP. To obtain the right K/Ms combination, nanocomposites containing exchange-coupled hard and soft magnetic phases were designed. A representative example was the exchange-coupled core/shell NPs composed of magnetically hard CoFe2O4 (K = 2×105 J m-3) core and magnetically soft MnFe2O4 shell (K = 3×103 J m-1). The exchange-coupled 15 nm CoFe2O4/MnFe2O4 NPs maintained the superparamagnetism at room temperature and had a K of 1.5×104 J m-3, which is in the optimal K range. The core/shell NPs had an appropriately 5 times higher SLP value of 2280 W g-1 compared to single component NPs (443 W g-1 for the CoFe2O4 NPs and 411 W g-1 for the MnFe2O4 NPs) 145. So far, significant progress for the fabrication of magnetic nanoparticles with controlled size and shape has been made toward the production of monodisperse populations for enhanced SAR or SLP, to guarantee high temperatures for hyperthermia treatment.

Figure 13.

Magnetic hyperthermia properties of various IONPs. (A) A homemade device for magnetically induced hyperthermia. The magnetic hyperthermia properties (SAR or SLP value) of IONPs influenced by (B) size, (C) the value of Hf, (D) the frequency of the magnetic field, (E) the shape of the particles, and (F) their concentration. (A, B) Reproduced with permission from 62, copyright 2007. (C) Reproduced with permission from 61, copyright 2012. (D) Reproduced with permission from 150, copyright 2011. (E, F) Reproduced with permission from 146, copyright 2013.

Significant progress in methods to prepare magnetic nanoparticles of controlled size and shape has been made toward the production of monodisperse populations for enhanced SAR or SLP. Future progress in the field will be made possible by further gains in monodispersity and by precise control or measurement of anisotropy within nanoparticle populations. However, there is significantly more consistency among experimental results than is generally assumed. Due to the absence of a depth penetration limit for magnetic fields in the human body, IONPs have been one of the ideal platform materials for theranostics of biological objects. However, the current developmental stage of theranostic nanoparticles is still too early to predict their success, but rapid advances in new design concepts for next-generation nanoparticles have promising potential in that avenue 120, 151.

Targeted drug delivery

The primary shortcomings of conventional chemotherapeutic agents are their nonspecific targeting, rapid clearance from the body and side effects toward healthy tissues. Since the pioneering idea that fine iron particles could be transported through the vascular system and be concentrated at a specific site in the body with the aid of a magnetic field, the application of magnetic nanoparticles to deliver drugs or antibodies to organs or tissues has become an active and attractive field of research 152, 153. Zimmermann and Pilwat made the first attempt to applying IONPs as carriers of chemotherapeutic agents in 1976 and they used magnetic erythrocytes for the delivery of cytotoxic methotrexate 154. Then, for the first time, Lubbe et al. tested the targeting efficacy of epirubicin-loaded MNPs for pancreas cancer in vivo 155. In recent years, IONPs have come as a boon with many advantages: nano-scaled size for drug delivery, heat-responsive drug delivery when combined with magnetically mediated hyperthermia (MMH) and drug targeting for site-specific delivery of therapeutic agents.

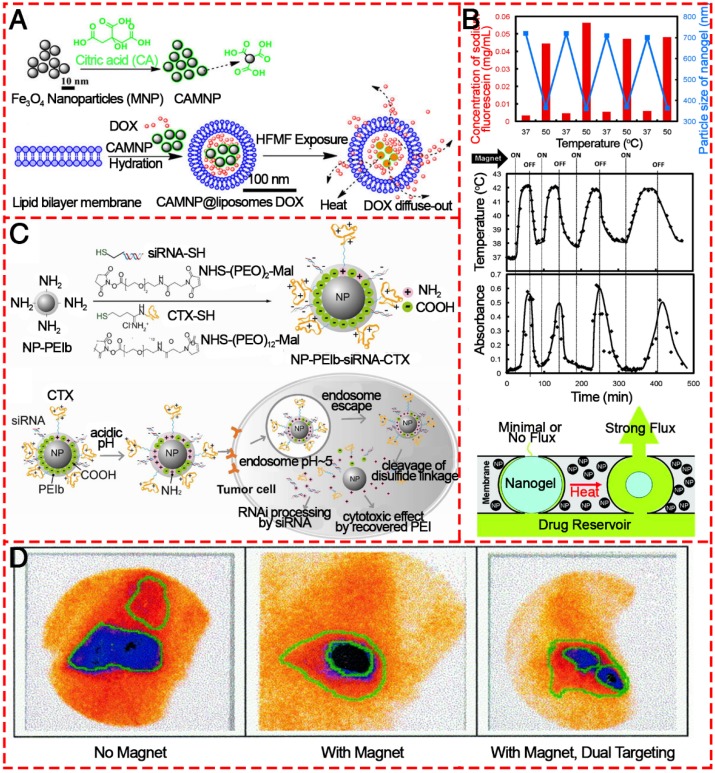

In order to prepare efficient targeted drug delivery system based on magnetic materials, typically, drug molecules and a magnetic moiety are formulated into a pharmacologically stable formulation by applying polymers, liposomes, inorganic materials, proteins, etc. (Figure 14) 117, 118, 156-159. Hardiansyah et al. developed drug-loaded magnetic liposomes for cancer treatment by the combination of chemotherapy and thermotherapy (Figure 14A) 156. When the magnetic liposomes loaded with 1 μM doxorubicin was used to treat CT-26 cells in combination with high-frequency magnetic field (HFMF) exposure, ~56% of cells were killed, which was more effective than chemotherapy without HFMF treatment. Due to the heat-inducing ability of IONPs in the as-prepared formulation, the release of loaded drugs could be precisely controlled. After a large quantity of drug is administered, an external alternating magnetic field could trigger the IONPs to produce heat to trigger the drug release process. It realized little or no drug release in the “off” state and rapid release when was switched to the “on” state without mechanically disrupting the device (Figure 14B) 158. In addition to the delivery of antitumor drugs, IONPs conjugated with siRNAs directly by covalent bonds or by physical adsorption onto their surfaces have been widely studied as siRNA carriers 160. Mok et al. successfully immobilized both anti-GFP siRNA and chlorotoxin (CTX) onto IONPs as a therapeutic moiety and targeting ligand for glioma, respectively (Figure 14C) 157. The CTX conjugation to the nanoparticles induced significantly enhanced intracellular uptake by C6 glioma cells.

Figure 14.

Various IONPs as agents for targeted drug delivery. (A) Diagram showing the proposed synthesis of surface-modified IONPs using citric acid and the preparation of DOX-loaded magnetic liposomes and their interaction with high frequency magnetic field. Reproduced with permission from 156, copyright 2014. (B) Schematic illustrating the intracellular uptake, extracellular trafficking and processing of NP-PEIb-siRNA-CTX (NP: iron oxide nanovector; PEIb: highly amine blocked polyetherimide; CTX: chlorotoxin) in tumor cells. Reproduced with permission from 157, copyright 2010. (C) Stimulus-responsive magnetic triggering induced heating in vitro based on IONPs. Reproduced with permission from 158, copyright 2009. (D) Gamma camera images of the abdominal region of a swine after administration of 99mTc-MTC based on magnetic targeting. Reproduced with permission from 153, copyright 1999.

Magnetic drug targeting allows the concentration of drugs at a defined target site generally and, importantly, away from organs of the MPS with the aid of a magnetic field. Alexiou et al. treated squamous cell carcinoma in rabbits with ferrofluids bound to mitoxantrone (FF-MTX), which was concentrated in the desired area with an external magnetic field. This “magnetic drug targeting” offers a unique opportunity to treat malignant tumors locoregionally without systemic toxicity (Figure 14D) 161. Based on this concept, coating the IONPs with amphiphilic polymeric surfactants such as poloxamers, polyethyleneimine (PEI) and PEG derivatives is an efficient way to avoid the MPS and increase accumulation at specific sites. Chertol et al. examined the applicability of PEI-modified magnetic nanoparticles (GPEI) as a potential vascular drug/gene carrier to brain tumors and showed that magnetic accumulation of cationic GPEI in tumor lesions was 5.2-fold higher than that achieved with slightly anionic G100 following intra-carotid administration 162. To further increase the targeting efficiency and to enhance the specific accumulation of MNPs at the target site, several attempts have been made to attach targeting ligands. Santra et al. illustrated a kind of biocompatible, multimodal, and theranostic functional IONP for targeted cancer therapy and optical and magnetic resonance imaging 163. Folic acid was conjugated to drug-encapsulating IONPs via click chemistry, providing targeted drug delivery to cancer cells that overexpress the folate receptor, while avoiding normal cells that do not overexpress this receptor. When IONPs are used as targeted drug delivery systems, they are usually not the direct carrier, as are mesoporous silica or liposomes; instead, the drugs are loaded into the coating polymers. However, 3-dimensional IONPs like hollow nanospheres, nanotubes, and nanoflowers could be used as direct delivery systems. Moreover, apart from their drug delivery ability and magnetic targeting behavior triggered by an external magnetic field, IONPs have heating properties, which, as mentioned above, make them possible platforms for multifunctional treatment of cancer.

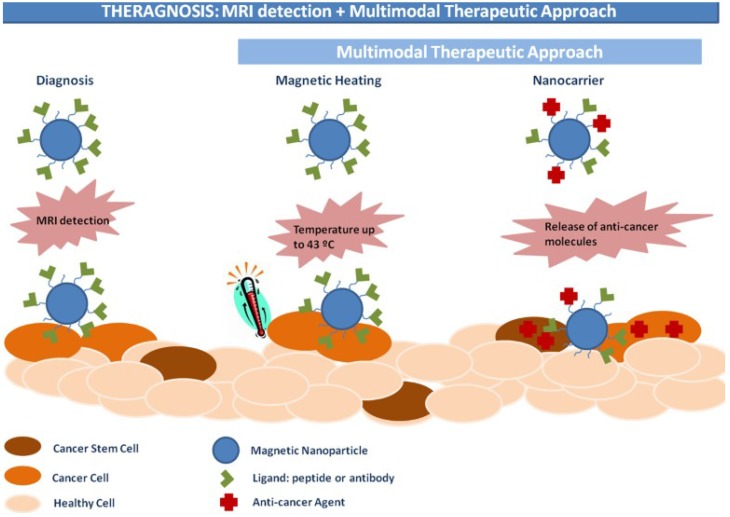

Magnetic theranostics

Magnetic theranostics, which combines MRI detection and other multimodal therapeutic approaches (Figure 15), could produce “nanoparticle-based drugs” with capabilities to both diagnose and treat cancer 164. The goal of magnetic theranostics is to provide a rapid review of the outcome of lesions both before and after treatment of an individual patient, and then to design and guide the next therapeutic strategies or to decide to repeat the same therapeutic process. In recent years, many magnetic theranostic formulations based on IONPs have been successfully developed via combination MRI with chemotherapy, phototherapy, photodynamic therapy, gene therapy, etc. The MRI-guided therapeutic strategy provides a way to realize optimal therapeutic efficiency, monitor therapeutic responses and personalize medicine 165.

Figure 15.

Schematic illustration of IONPs for magnetic theranostics. Reproduced with permission from 164, copyright 2015.

In order to integrate therapeutic agents with IONPs-based MRI to perform magnetic theranostics, self-assembly and surface modification are usually used for the synthesis. Liu et al. prepared mesoporous silica (MS)-coated, IONPs-decorated tungsten disulfide (WS2) nanosheets via self-assembly of MS and surface modification with PEG, which showed excellent physiological stability and low cytotoxicity for imaging-guided combination cancer therapy 166. The as-synthesized WS2-IO@MS-PEG nanostructures exhibited tri-modal fluorescence, MR and computed tomography (CT) imaging abilities and combined photothermal and chemotherapy delivered by WS2-IO@MS-PEG/DOX. Similarly, Shi et al. reported the use of hyaluronic acid-modified IO@Au core/shell nanostars for tri-modal MR, CT, and thermal imaging-guided phototherapy of tumors 167. The particle's water dispersibility and biocompatible properties together with MR/CT imaging and photothermal therapy made it a multifunctional nano-platform for efficient magnetic theranostics of different types of cancer. Besides MRI-guided chemotherapy or photothermal therapy, IONPs are also excellent delivery systems with gene transfer capabilities. A fluorescent IONP with gene transfection capability was assembled by grafting PEI onto the IONP surface followed by rhodamine B isothiocyanate (RITC) binding onto the PEI polymer. The obtained IONPs-PEI-RITC magnetic nanoparticles with multimodal MRI-fluorescence imaging and transfection capability proved a valuable 'magnetic theranostic' tool for the development and clinical translation of neural cell therapies 168. To realize magnetic theranostics, it is normally required that IONPs should be integrated with other therapeutic agents, which may result in a more complicated preparation process. Therefore, the simplest magnetic theranostic platform is IONPs themselves for their own MRI and magnetic hyperthermia properties. Feng et al. prepared hydrophilic IONPs (IO-250) through a one-pot polyol decomposition route 169. The IO-250 exhibited a promising MRI relaxivitiy with a r2 value of 617.5 mM-1s-1 and could produce a significant temperature rise under an alternating magnetic field, indicating that it is a promising candidate for clinical MRI-guided tumor magnetic hyperthermia treatment.

Currently, a number of IONPs are in early clinical trials or experimental study stages, and several formulations have been approved for clinical use for medical imaging and therapeutic applications. Notable examples include: Lumiren® for bowel imaging, Feridex IV® for liver and spleen imaging, Combidex® for lymph node metastases imaging, Ferumoxytol® for iron replacement therapy, and, most recently, NanoTherm® for local treatment of solid tumors 85. Magnetic theranostics is one of the best strategies to realize the individual, visual, and integrated requirements of cancer treatment or personalized medicine; therefore, many studies are anticipated.

Conclusion and perspective

There have been continuous advances in the development of engineered IONPs that can be utilized as theranostic tools. Research into the implementation of multimodal approaches based on IONPs will open up new and highly sophisticated methods of diagnosis and therapy of tumor pathologies. Various facile methods have been explored for rapid and simple development of IONPs with controllable shape, size, structure, chemical and physical surface properties, and outstanding biological properties. Moreover, the theranostic applications of IONPs including both T1- and T2-weighted MRI, magnetic hyperthermia, and drug delivery are dependent on their shape, size, structure and various functionalized surface modifications. Of all the nanomaterials applied for theranostics, their excellent functional nature is one of IONPs' most significant properties. The more challenging aspect is to design biocompatible IONPs with both in vitro and in vivo degradation and metabolization.

The present review summarized some of the progress relating to this field to give a clear picture of the existing knowledge and the wide application of IONPs for theranostic applications and clinical translation. Despite significant progress in IONPs platforms, gaps in technical knowledge continue to prevent translation from bench to bedside. Further works are still waiting to be improved and completed in the near future.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 81671829 and 51673107).

Abbreviations

- IONPs

iron oxide nanoparticles

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- PEG-400

polyethylene glycol 400

- MAH

microwave-assisted hydrothermal

- NaAc

sodium acetate

- EG

ethylene glycol

- PDA

1, 3-propanediamine

- TNPs

triangular nanoprisms

- TBAB

tetra-n-butylammonium bromide

- EPR

enhanced permeability and retention

- DSPE-PEG

carboxyl-terminated poly(ethylene glycol)-phospholipid

- NRs

nanorings

- QDs

quantum dots

- NHLF

normal human lung fibroblast cells

- QD-FVIOs

quantum dots-ferrimagnetic vortex-state iron oxide nanorings

- RMF

rotating magnetic field

- SRB

sulforhodamine B

- MSPs

magnetic submicron particles

- MPS

mononuclear phagocyte system

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

- PVA

polyvinyl alcohol

- PEI

polyethylenimine

- PAA

polyacrylic acid

- PLGA

poly(lactide-co-glycolide)

- TEOS

tetraethyl orthosilicat

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- MR

magnetic resonance

- EMA

european medicines agency

- ES-MIONs

extremely small magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles

- NPs

nanoparticles

- SDR

static dephasing regime

- NRs

nanorods

- MNP

magnetic nanoparticles

- IO

iron oxide

- MRA

magnetic resonance angiography

- AFIA

artifact filtering nanoparticle imaging agent

- CA

contrast agent

- uIONPs

ultrafine iron oxide nanoparticles

- MHT

magnetic hyperthermia

- MPH

magnetic particle hyperthermia

- SPION

superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles

- SAR

specific absorption rate

- SLP

specific loss power

- IONCs

iron oxide nanocubes

- MMH

magnetically mediated hyperthermia

- HFMF

high-frequency magnetic field

- CTX

chlorotoxin

- FF-MTX

ferrofluids bound to mitoxantrone

- GPEI

PEI-modified magnetic nanoparticles

- MS

mesoporous silica

- CT

computed tomography

- RITC

rhodamine B isothiocyanate.

References

- 1.Bazylinski DA, Frankel RB. Magnetosome formation in prokaryotes. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:217–230. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diebel CE, Proksch R, Green CR, Neilson P, Walker MM. Magnetite defines a vertebrate magnetoreceptor. Nature. 2000;406:299–302. doi: 10.1038/35018561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Falkenberg G, Fleissner G, Schuchardt K, Kuehbacher M, Thalau P, Mouritsen H. et al. Avian magnetoreception: Elaborate iron mineral containing dendrites in the upper beak seem to be a common feature of birds. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9231. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ali A, Zafar H, Zia M, Haq Iu, Phull AR, Ali JS. et al. Synthesis, characterization, applications, and challenges of iron oxide nanoparticles. Nanotechnol Sci Appl. 2016;9:49–67. doi: 10.2147/NSA.S99986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu G, Men P, Harris PLR, Rolston RK, Perry G, Smith MA. Nanoparticle iron chelators: A new therapeutic approach in alzheimer disease and other neurologic disorders associated with trace metal imbalance. Neurosci. Lett. 2006;406:189–193. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mahmoudi M, Sant S, Wang B, Laurent S, Sen T. Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (spions): Development, surface modification and applications in chemotherapy. Adv. Drug Del. Rev. 2011;63:24–46. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang L, Dong W-F, Sun H-B. Multifunctional superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: Design, synthesis and biomedical photonic applications. Nanoscale. 2013;5:7664–7684. doi: 10.1039/c3nr01616a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mahmoudi M, Hofmann H, Rothen-Rutishauser B, Petri-Fink A. Assessing the in vitro and in vivo toxicity of superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles. Chem. Rev. 2012;112:2323–2338. doi: 10.1021/cr2002596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosen JE, Chan L, Shieh D-B, Gu FX. Iron oxide nanoparticles for targeted cancer imaging and diagnostics. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2012;8:275–290. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2011.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xie Y, Liu D, Cai C, Chen X, Zhou Y, Wu L. et al. Size-dependent cytotoxicity of Fe3O4 nanoparticles induced by biphasic regulation of oxidative stress in different human hepatoma cells. Int. J. Nanomed. 2016;11:3557–3570. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S105575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]