Abstract

Glaucoma is a major cause of visual impairment characterized by progressive retinal neurodegeneration. Circular RNAs are a class of endogenous noncoding RNAs that regulate gene expression in eukaryotes. In this study, we investigated the role of cZNF609 in retinal neurodegeneration induced by glaucoma.

Methods: qRT-PCR and Sanger sequencing were conducted to detect cZNF609 expression pattern during retinal neurodegeneration. Immunofluorescence staining was conducted to detect the effect of cZNF609 silencing on retinal neurodegeneration in vivo. MTT assay, Ki67 staining, and PI staining were conducted to detect the effect of cZNF609 silencing on retinal glial cells and RGC function in vitro. Bioinformatics analysis, RNA pull-down assays, and in vitro studies were conducted to reveal the mechanism of cZNF609-mediated retinal neurodegeneration.

Results: cZNF609 expression was significantly up-regulated during retinal neurodegeneration. cZNF609 silencing reduced retinal reactive gliosis and glial cell activation, and facilitated RGC survival in vivo. cZNF609 silencing directly regulated Müller cell function but indirectly regulated RGC function in vitro. cZNF609 acted as an endogenous miR-615 sponge to sequester and inhibit miR-615 activity, which led to increased METRN. METRN overexpression could partially rescue cZNF609 silencing-mediated inhibitory effects on retinal glial cell proliferation.

Conclusion: Intervention of cZNF609 expression is a promising therapeutic strategy for retinal neurodegeneration.

Keywords: circular RNA, microRNA sponge, glaucoma, retinal neurodegeneration

Introduction

Neurodegenerative diseases affect millions of people worldwide and have become the most pressing problems in developed countries. A broad range of neurodegenerative disorders, including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Parkinson's, Alzheimer's, Huntington's, and glaucoma, are usually characterized by neuronal damage 1, 2. They have several common pathological features, such as oxidative stress, inflammation, and hypometabolism 3. As the extension of central nervous system (CNS), the retina displays many similarities to the brain and spinal cord in terms of anatomy, functionality, response to insult, and immunology 4. Moreover, several well-defined neurodegenerative conditions that affect the brain and spinal cord have manifestations in the eye 5. Thus, clarifying the mechanism of retinal neurodegeneration would provide novel insight into the pathogenesis of other neurodegenerative disease 6.

Glaucoma is a retinal neurodegenerative disease characterized by progressive gradual loss of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) and axons 7. The risk factors, including intraocular hypertension, age, vascular dysfunction, corneal thickness and ethnic origin, are tightly associated with the pathogenesis of glaucoma 8. Current methods for glaucoma treatment mainly include surgery and pharmaceuticals. These methods could partially delay the progression of glaucoma and rescue visual field and RGC survival. Stem cell transplantation is beneficial for several retinal neurodegenerative diseases. Previous study has found the transdifferentiation of human periodontal ligament-derived stem cells into functional retinal ganglion-like cells, and identified miR-132, VEGF and PTEN as key regulators in retinal fate determination of human adult stem cells 9. Intravitreal transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) has also been shown to be a neuroprotective therapy for glaucoma in an animal model 10. Reducing intraocular pressure is still the major therapeutic strategy for glaucoma. However, despite effective medical and surgical therapies to reduce intraocular pressure, progressive vision loss is common 11, 12. Thus, further study is still required to clarify the precise mechanism of retinal neurodegeneration in glaucoma.

Circular RNAs (circRNAs) are a class of endogenous RNAs characterized by covalently closed continuous loop structures. They are highly abundant, conserved, and dynamically expressed in the CNS 13, 14. circRNAs regulate gene expression by acting as microRNA sponges, nuclear transcriptional regulators, protein sponges, protein scaffolds, or by showing translation potentials 15, 16. Accumulating studies have revealed that several circRNAs are dysregulated in many neurodegenerative diseases 13, 17, 18. However, the role of circRNA in retinal neurodegenerative diseases, especially in glaucoma, is still unclear.

cZNF609 has been found to be expressed in neurons and endothelial cells 14, 19. It is an important regulator of tumorigenesis, myogenesis, and vascular dysfunction 20-22. We have shown that cZNF609 is involved in ischemia-induced retinal vascular dysfunction 22. Blood vessels and nerves are two important channels in vivo and usually share the common regulators of differentiation, growth, and navigation 23, 24. We speculated that cZNF609 also plays an important role in retinal neurodegeneration. In this study, we investigated the expression pattern of cZNF609 and the role of cZNF609 in retinal neurodegeneration induced by glaucoma.

Methods

Ethics statement

All animal experiments were performed according to the guidelines of the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (published by National Institutes of Health) and the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. The animal experiments were also approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Eye & ENT Hospital.

Episcleral vein ligation-induced glaucoma model

Sprague-Dawley (SD, male, 200-250 g) rats were used for building the glaucoma model through the ligation of three episcleral veins. In brief, the rats were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of xylazine (10 mg/kg) and ketamine (75 mg/kg) mixture before surgery. The conjunctiva and Tenon's capsule of the left eyes were incised to expose the episcleral veins. Each vein was isolated from the surrounding tissue, ligated with 10-0 nylon suture, and then severed. The control group received the sham surgery expect for the ligation and severance. Intraocular pressure (IOP) was detected using a digital tonometer between 10 AM and 2 PM to avoid the effect of circadian rhythm 25.

Microbead injection-induced glaucoma model

Sprague-Dawley (SD, male, 200-250 g) rats were used for building the glaucoma model through chamber injection of microbeads. Briefly, the rats were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of xylazine (10 mg/kg) and ketamine (75 mg/kg) mixture. During the microbead surgery, one eye was injected with the sterile microbeads, and the control group was injected with an equivalent volume of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). After the injection, antibiotic drops (0.5% moxifloxacin hydrochloride ophthalmic solution) were placed on each eye. The animal was allowed 24 h recovery before IOP detection. Four weeks after the injection, the second microbead injection was conducted in the above-mentioned animals. IOP was detected using a digital tonometer between 10 AM and 2 PM to avoid the effect of circadian rhythm 26.

Immunofluorescence staining

The rat eyes were removed, punctured with a fine gauge needle, and placed in 4% PFA at 4 °C for 12 h. Eyes were then cryoprotected in 30% sucrose for 12 h, embedded in OCT medium (Sakura Finetek). ~10 µm tissue sections were cut using a cryostat (Thermo Scientific) and collected on poly-L-lysine coated slides. Retinal slices were permeabilized with PBS solution containing 0.15% Triton X-100 for 30 min and incubated with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 h to block non-specific antibody binding. Retinal slices were then incubated with the following primary antibodies: TUJ1 (1:300, Abcam), GFAP (1:200, Abcam), GS (1:200, Abcam), Calretinin (1:500, Chemicon), Rhodopsin (1:1,000, Sigma), protein kinase Cα (PKCα, 1:200, Abcam), and Nestin (1:100, Santa Cruz) at 4 °C for 24 h. The slices were washed with PBS and then incubated with the secondary antibody (Invitrogen) overnight at 4 °C. The slides were finally mounted and observed.

Cell culture

Retinal glial cells line (rMC-1) and primary RGCs were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

RNA pull down assay

The 3' end of biotinylated miR-615 or control mimic RNA was transfected into retinal glial cells at a concentration of 30 nM for 24 h. The biotin-coupled RNA complex was pulled down by incubating the cell lysates with streptavidin-coated beads (Life Technologies). The cZNF609 amount in the bound fraction was detected by qRT-PCR.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. The significant difference was determined by two-tailed Student's t test (two-group comparisons) or one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Bonferroni test (multi-group comparisons) as appropriate. P<0.05 was considered statistical significance.

Result

cZNF609 expression is significantly up-regulated during retinal neurodegeneration

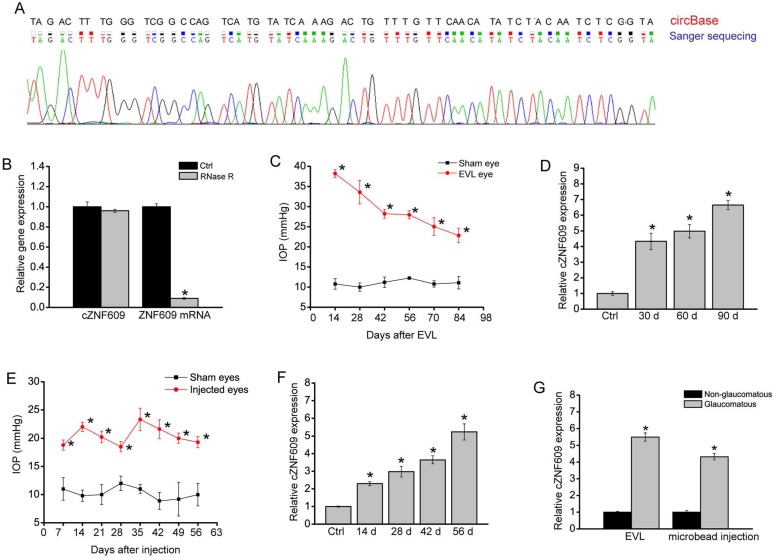

cZNF609 has been reported to be expressed in endothelial cells and tumor cells 20, 22. In this study, we first confirmed its expression in rat retinas. The amplified product of cZNF609 was sent for sequencing. Sanger sequencing showed that rat cZNF609 sequence was completely in accordance with the mouse cZNF609 sequence (mmu_circ_0001797), as shown in circBase (Figure 1A). cZNF609 was resistant to RNase R digestion, whereas linear ZNF609 mRNA was easily degraded (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

cZNF609 expression is significantly up-regulated during retinal neurodegeneration. (A) The amplified product of cZNF609 using total RNAs from rat retinas was sent for Sanger sequencing. (B) Total RNAs from rat retinas were digested with RNase R followed by qRT-PCR detection of cZNF609 expression. ZNF609 mRNA was detected as the RNase R-sensitive control (n=4). (C) IOP levels in the sham eyes or EVL eyes are shown (n=5). (D) qRT-PCRs were conducted to detect cZNF609 expression in the retinas of rats after EVL at the indicated time points (n=5 animals per group). (E) IOP levels in the sham eyes (saline injection) and microbead injection (injected eyes) are shown (n=5). (F) qRT-PCRs were conducted to detect cZNF609 expression in the retinas of rats after microbead injection at the indicated time points (n=5). (G) qRT-PCRs were conducted to detect cZNF609 expression in the aqueous humor of glaucomatous rats induced by EVL or microbead injection (n=5).

We used the episcleral vein ligation (EVL) method to build a rat model of glaucoma. EVL led to a significant increase in IOP level compared to that of the control group without EVL (Figure 1C). Moreover, EVL led to a significant increase in cZNF609 expression (Figure 1D). We also built another rat model of glaucoma by chamber injection of microbeads to impede aqueous outflow. Microbead injection led to a significant elevation in IOP level (20-25 mmHg), which was about two times higher than normal IOP level. The elevation was maintained for another 4 weeks with a second microbead injection, compared to the steady level of 10 mmHg of IOP in the control eyes (Figure 1E). qRT-PCR assays showed that elevated IOP significantly up-regulated cZNF609 expression level (Figure 1F). We also revealed that cZNF609 levels in the aqueous humor of glaucomatous rat eyes were higher than those of non-glaucomatous eyes (Figure 1G).

cZNF609 silencing regulates retinal reactive gliosis and RGC survival in vivo

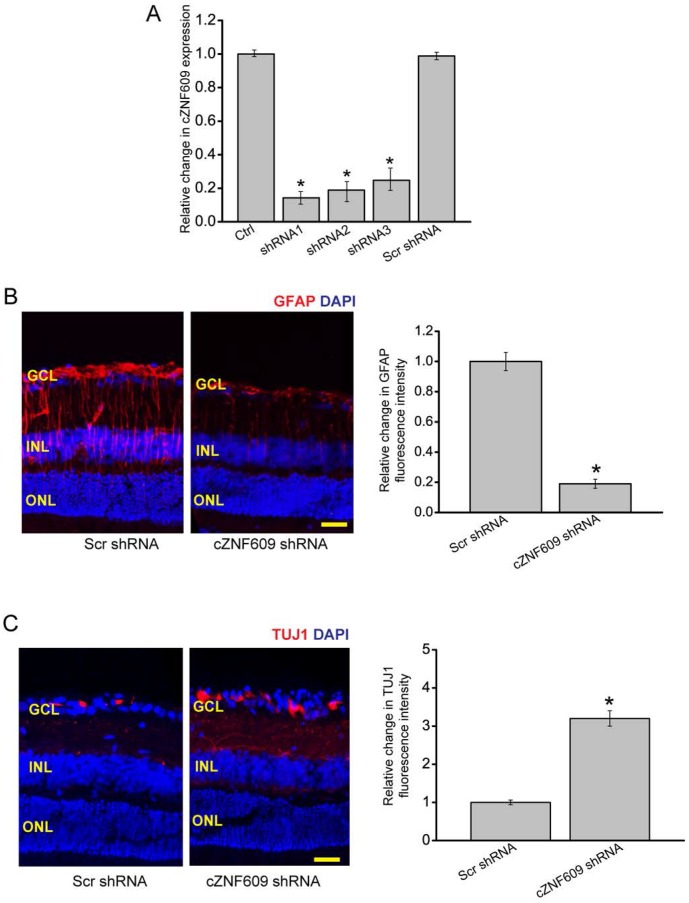

To investigate the role of cZNF609 in glaucoma-induced retinal neurodegeneration, we designed three different shRNAs for cZNF609 silencing. All of them could significantly decrease cZNF609 expression (Figure 2A). We selected cZNF609 shRNA1 for cZNF609 silencing because it has the greatest silencing efficiency.

Figure 2.

cZNF609 silencing regulates retinal reactive gliosis and RGC survival in vivo. (A) The rat retinas were injected with scrambled shRNA (Scr), cZNF609 shRNA-1, cZNF609 shRNA-2, cZNF609 shRNA-3, or left untreated for 48 h. qRT-PCRs were conducted to detect cZNF609 expression (n=4, *P<0.05 versus Ctrl). (B-C) Three months after EVL, retinal slices were stained with GFAP (B) and TUJ1 (C) to detect retinal reactive gliosis and RGC survival (n=5, *P<0.05 versus Scr shRNA). Scale bar, 100 µm. GCL: ganglion cell layer; INL: inner nuclear layer; ONL: outer nuclear layer.

We used the EVL method to establish a rat model of glaucoma. The glaucomatous eyes received an intravitreal injection of scrambled shRNA or cZNF609 shRNA. We employed immunofluorescence staining to determine the effect of cZNF609 silencing on retinal neurodegeneration. Compared with EVL-induced glaucomatous eyes, cZNF609 silencing led to decreased reactive gliosis (decreased GFAP staining) and increased TUJ1 (class III β-tubulin) positive RGCs (Figure 2B-C). Retinal slices were also immunolabeled with Calretinin (ganglion cells and amacrine cells), Rhodopsin (Rod and cone photoreceptor), and protein kinase Cɑ (PKCɑ; bipolar cells) to determine the effect of cZNF609 silencing on other retinal cell types. Compared with EVL-treated eyes, cZNF609 silencing increased the number of calretinin-labeled cells in the GCL, but did not further affect the number of Calretinin-labeled cells in the INL. We did not detect a staining difference of Rhodopsin and PKCɑ between the scrambled shRNA-injected group and the cZNF609 shRNA-injected group (Figure S1).

We also used microbead injection-induced glaucomatous rats to determine the effect of cZNF609 silencing on retinal neurodegeneration. We observed a similar scenario in microbead injection-induced glaucomatous retinas as shown in EVL-treated retinas. cZNF609 silencing decreased retinal reactive gliosis, and protected RGCs against glaucoma-induced injury. cZNF609 silencing did not affect the staining signaling of amacrine cells, photoreceptors, or bipolar cells (Figure S2).

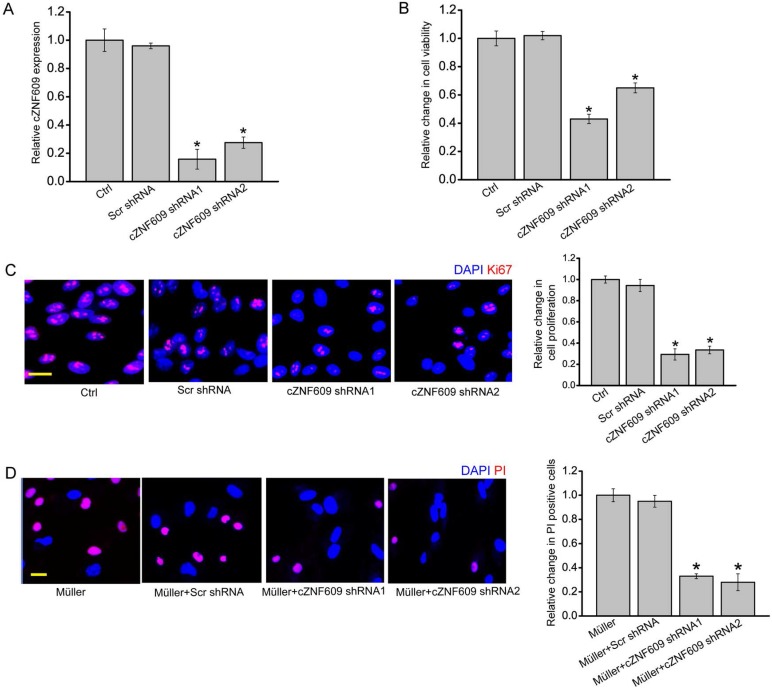

cZNF609 silencing directly regulates Müller cell function but indirectly regulates RGC function in vitro

The above-mentioned results showed that cZNF609 mainly regulated Müller cell and RGC function. We then studied the mechanistic aspects and functional significance of cZNF609 expression change in vitro. cZNF609 shRNA transfection significantly decreased cZNF609 expression in Müller cells (Figure 3A). MTT and Ki67 staining assays showed that cZNF609 silencing significantly decreased Müller cell viability and proliferation (Figure 3B-C). cZNF609 shRNA transfection significantly decreased cZNF609 expression in primary RGCs (Figure S3A). However, cZNF609 silencing did not affect RGC viability and proliferation (Figure S3B-C). We also used an in vitro RGC-Müller cell co-culture system to determine whether cZNF609 silencing in Müller cells had an indirect effect on RGC function. Mechanisms involved in RGC damage in glaucoma mainly include oxidative injury and glutamate toxicity 27, 28. PI staining revealed that cZNF609 silencing in Müller cells obviously attenuated the pro-apoptotic effect of Müller cells on RGCs in response to H2O2 or glutamate toxicity (Figure 3D and Figure S3D). Collectively, these results suggest that cZNF609 directly regulates Müller cell function but indirectly regulates RGC function in vitro.

Figure 3.

cZNF609 silencing directly regulates Müller cell function but indirectly regulates RGC function in vitro. (A) Müller cells were transfected with scrambled shRNA (Scr), cZNF609 shRNA1, cZNF609 shRNA2, or left untreated (Ctrl) for 24 h. qRT-PCRs were conducted to detect cZNF609 expression (n=4, *P<0.05 versus Ctrl). (B) The viability of Müller cells was detected by the MTT method. The data is shown as relative change compared with the Ctrl group (n=4, *P<0.05 versus Ctrl). (C) Ki67 staining was conducted to detect the proliferation of Müller cells (n=4, *P<0.05 versus Ctrl group). Scale bar: 20 μm. (D) RGCs were co-cultured with or without wild-type Müller cells, Scr shRNA-transfected Müller cells, cZNF609 shRNA1-transfected Müller cells, or cZNF609 shRNA2-transfected Müller cells, and then treated with H2O2 (100 μm) for 24 h. PI staining and quantitative analysis was conducted to detect apoptotic RGCs. *P<0.05 versus Müller cell group.

cZNF609 silencing regulates retinal glial activation in vivo

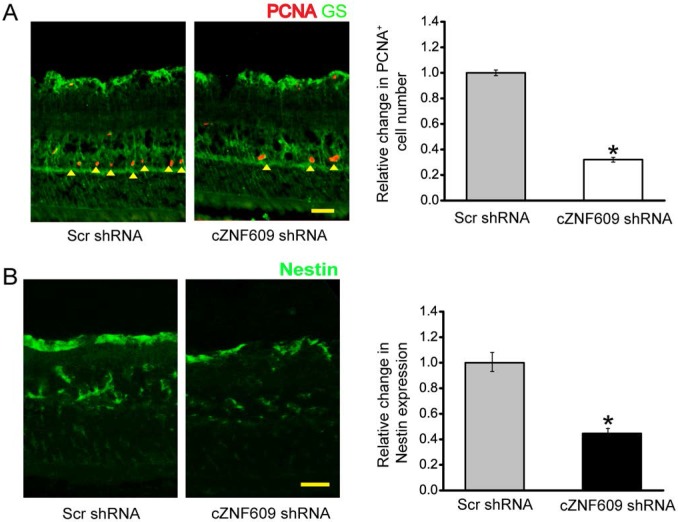

Retinal glia cells have the capability to dedifferentiate and reenter the proliferation cycle under stress conditions 24. We thus determined whether cZNF609 silencing affected the regenerative ability of retinal glial cells in vivo. We labeled the proliferating retinal cells by PCNA staining. Injection of cZNF609 shRNA significantly decreased the number of PCNA-positive cells in EVL- or microbead injection-induced glaucomatous retinas. PCNA-stained cells also overlapped with glutamine synthetase (GS) staining (Figure 4A and Figure S4A), suggesting that cZNF609 silencing affects retinal glial proliferation. The reactivation of stem and progenitor properties of glial cells further prompted us to determine the effect of cZNF609 silencing on the expression of progenitor markers such as Nestin 24. cZNF609 silencing significantly decreased the expression of Nestin in EVL- or microbead injection-induced glaucomatous retinas (Figure 4B and Figure S4B).

Figure 4.

cZNF609 silencing affects retinal glial cell activation in vivo. (A) Three months after EVL, retinal slices were stained with PCNA and GS antibody to label retinal glial cell proliferation. (B) Retinal slices were stained with a progenitor marker, Nestin, to detect the effect of cZNF609 silencing on the reactivation of stem and progenitor properties of glial cells. Scale bar, 100 µm. GCL: ganglion cell layer; INL: inner nuclear layer; ONL: outer nuclear layer; *P<0.05 versus Scr shRNA.

cZNF609-miR-615-METRN is involved in regulating Müller cell function

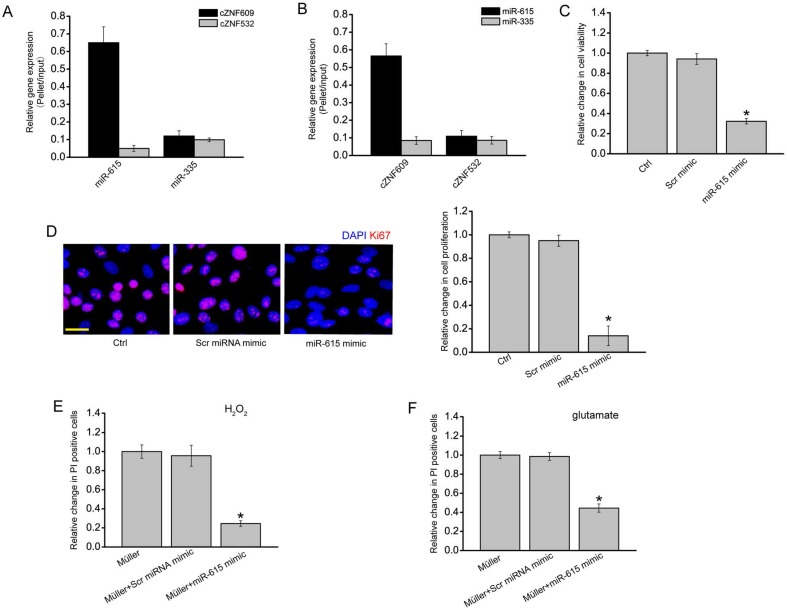

In our previous study, we revealed that cZNF609 regulates endothelial cell function by acting as a miR-615 sponge 22. In Müller cells, RNA pull-down assays showed that cZNF609 was enriched in the miR-615-captured fraction compared to the negative control, biotinylated miR-335 (Figure 5A). Moreover, miR-615 was enriched in the cZNF609-captured fraction compared to the negative control, biotinylated cZNF532 (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

cZNF609-miR-615-METRN is involved in regulating Müller cell function. (A) The 3'-end biotinylated miR-615 or miR-335 (negative control) duplexes were transfected into Müller cells. After the streptavidin capture, the amount of cZNF609 and cZNF532 (negative control) in the input and bound fraction was detected by qRT-PCRs. (B) The 3'-end biotinylated cZNF609 or cZNF532 was transfected into Müller cells. After the streptavidin capture, the amount of miR-615 and miR-335 in the input and bound fraction was detected by qRT-PCRs. (C-D) Müller cells were transfected with scrambled miRNA mimic (Scr), miR-615 mimic, or left untreated for 24 h. MTT assays (C) and Ki67 staining (D) were conducted to detect cell viability and proliferation (n=4, *P<0.05 versus Ctrl group). Scale bar: 20 μm. (E-F) RGCs were co-cultured with or without wild-type Müller cells, miR-615 mimic-transfected Müller cells, or Scr miRNA mimic-transfected Müller cells, and then treated with 100 μm H2O2 (E) or 3 mM glutamate (F) for 24 h. PI staining and quantitative analysis were conducted to detect the apoptotic RGCs. *P<0.05 versus Müller cell group.

We then determined the role of miR-615 in Müller cells. miR-615 mimic transfection significantly decreased Müller cell viability and proliferation (Figure 5C-D). Müller cell and RGC co-culture and PI staining assays showed that miR-615 mimic transfection in Müller cells obviously attenuated the harmful effect of Müller cells on RGC function in response to H2O2 or glutamate treatment, which could mimic cZNF609 silencing (Figure 5E-F).

We them employed the Targetscan database to predict the target gene of miR-615. One of the candidate genes, meteorin (METRN), aroused our interest due to its role in cell differentiation and proliferation 29, 30. miR-615 mimic transfection significantly reduced METRN expression (Figure S5A). Luciferase reporter assay further verified the direct regulation of miR-615 on METRN expression (Figure S5B). We also revealed that cZNF609 silencing significantly reduced METRN expression (Figure S5C). Moreover, cZNF609 silencing-induced inhibition of glial cell proliferation could be partially reversed by METRN overexpression (Figure S5D).

Discussion

Glaucoma is a neurodegenerative disease with complex etiology and pathogenesis. Neuroprotection is a promising therapeutic method for preventing, retarding, and reversing retinal neurodegenation induced by glaucoma 7, 31. In this study, we show that cZNF609 silencing inhibits retinal reactive gliosis, glial cell activation, and contributes to RGC survival in glaucoma. cZNF609 silencing directly regulates Müller cell function but indirectly regulates RGC function in vitro. cZNF609 acts as miR-615 sponge to sequester and inhibit miR-615 activity, which leads to increased METRN. This study provides novel insights for understanding the pathogenesis of retinal neurodegeneration.

Under the normal condition, retinal glial cells support the functions of neurons via several mechanisms, including the removal of extracellular glutamate and synthesis of growth factors and metabolites 7. Retinal glial cells are activated during retinal neurodegeneration in glaucoma 32. GFAP, a marker of Müller cells, appears to be significantly elevated at the early stage of glaucoma and before widespread RGC apoptosis. Retinal glial activation leads to decreased biosynthesis of glutamate receptors 33. Moreover, activated glial cells exacerbate neuronal damage through the release of cytokines, reactive oxygen species, or nitric oxide 34, 35. These effects may lead to RGC apoptosis. cZNF609 is significantly up-regulated in retinal neurodegeneration induced by glaucoma. Increased cZNF609 expression could contribute to retinal reactive gliosis and glial cell activation. We speculate that cZNF609 silencing could reduce Müller cell-induced harmful effects on RGCs, which in turn facilitate RGC survival in glaucoma.

Müller glial cells greatly outnumber RGCs in the retina and have intimate relationships with RGCs 36. Müller glia contribute to several RGC functions, including synapse formation and plasticity, redox metabolism, and homeostasis of neurotransmitters and ions 37. H2O2 or glutamate treatment would alter the cytosecretion component of Müller cells. The addition of Müller cell culture medium increased the number of apoptotic RGCs. cZNF609 silencing in Müller cells obviously attenuated this harmful effect. Thus, cZNF609-mediated signaling is involved in RGC-glia interaction, and its dysregulation would affect the progression of retinal neurodegeneration induced by glaucoma.

We also investigated the mechanism of cZNF609-regulated retinal neurodegeneration. circular RNAs play their roles through several molecular mechanisms such as acting as miRNA sponges, RNA-binding protein sequestering agents, nuclear transcriptional regulators, or by showing translation potentials 15, 21, 38. As for cZNF609, previous studies have revealed that it mainly plays its role by acting as a miRNA sponge. cZNF609 takes part in the onset of Hirschsprung disease (HSCR) through crosstalk with AKT3 by competing for binding with miR-150-5p 20. cZNF609 acts as an endogenous miR-615-5p sponge to sequester and inhibit miR-615-5p activity in endothelial cells 22. In Müller cells, increased cZNF609 may sponge and sequester miR-615 in response to oxidative stress or glutamate excitotoxicity, releasing miR-615-mediated repressive effects on Müller cell function. A slight change in cZNF609 level may alter the balance of cZNF609/miR-615/target genes in the regulatory network.

Meteorin (METRN) is a secreted protein that has been previously reported to control neuritogenesis, angiogenesis, and gliogenesis. Meteorin plays important roles in both glial cell differentiation and axonal network formation during neurogenesis 29, 39. Meteorin also contributes to the formation of GFAP-positive glia via activation of the JAK-STAT3 pathway 30. METRN overexpression would partially reverse cZNF609 silencing-mediated inhibitory effects on Müller cell proliferation. During retinal neurodegeneration, cZNF609 overexpression becomes the sink of miR-615, and releases the miR-615-mediated inhibitory effect on METRN expression. METRN upregulation would contribute to Müller cell activation. This regulatory mechanism would provide novel insights into retinal neurodegeneration.

Conclusions

This study reveals that cZNF609 is an important regulator of retinal neurodegeneration. cZNF609 silencing inhibits retinal reactive gliosis and glial cell activation, and facilitates RGC survival. cZNF609 regulates retinal neurodegeneration through a regulatory network, which is composed of cZNF609, miR-615, and METRN. This study provides a promising target for treating retinal neurodegenerative diseases.

Acknowledgments

This work was generously supported by the grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81770945, 81430007, and 81790641), the top priority of clinical medicine center of Shanghai (2017ZZ01020), the grant from the Shanghai Youth Talent Support Program, and the grant from the Young Scientists Program from Eye & ENT Hospital.

Abbreviations

- circRNA

circular RNA, CNS: central nervous system, RGC: retinal ganglion cell, VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor, qRT-PCR: quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction, MTT: 3-[4,5-Dimethythiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide, METRN: Meteorin, DMEM: Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, FBS: fetal bovine serum, miRNA: microRNA

- GS

glutamine synthetase, IOP, intraocular pressure, EVL, episcleral vein ligation.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary methods and figures.

References

- 1.Barnham KJ, Masters CL, Bush AI. Neurodegenerative diseases and oxidative stress. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:205–14. doi: 10.1038/nrd1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forman MS, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VMY. Neurodegenerative diseases: a decade of discoveries paves the way for therapeutic breakthroughs. Nat Med. 2004;10:1055–63. doi: 10.1038/nm1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ransohoff RM. How neuroinflammation contributes to neurodegeneration. Science. 2016;353:777–83. doi: 10.1126/science.aag2590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paridaen JT, Huttner WB. Neurogenesis during development of the vertebrate central nervous system. EMBO Rep. 2014;15:351–64. doi: 10.1002/embr.201438447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.London A, Benhar I, Schwartz M. The retina as a window to the brain-from eye research to CNS disorders. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9:44–53. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saidha S, Sotirchos ES, Oh J, Syc SB, Seigo MA, Shiee N. et al. Relationships between retinal axonal and neuronal measures and global central nervous system pathology in multiple sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70:34–43. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Almasieh M, Wilson AM, Morquette B, Vargas JLC, Di Polo A. The molecular basis of retinal ganglion cell death in glaucoma. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2012;31:152–81. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta N, Yücel YH. Glaucoma as a neurodegenerative disease. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2007;18:110–4. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e3280895aea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ng TK, Yung JS, Choy KW, Cao D, Leung CK, Cheung HS. et al. Transdifferentiation of periodontal ligament-derived stem cells into retinal ganglion-like cells and its microRNA signature. Sci Rep. 2015;5:16429. doi: 10.1038/srep16429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McKinnon SJ. The cell and molecular biology of glaucoma: common neurodegenerative pathways and relevance to glaucoma. Invest Ophth Vis Sci. 2012;53:2485–7. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-9483j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wein FB, Levin LA. Current understanding of neuroprotection in glaucoma. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2002;13:61–7. doi: 10.1097/00055735-200204000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harwerth RS, Wheat JL, Fredette MJ, Anderson DR. Linking structure and function in glaucoma. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2010;29:249–71. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu D, Xu AD. Mini review: circular RNAs as potential clinical biomarkers for disorders in the central nervous system. Front Genet. 2016;7:53. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2016.00053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rybak-Wolf A, Stottmeister C, Glažar P, Jens M, Pino N, Giusti S. et al. Circular RNAs in the mammalian brain are highly abundant, conserved, and dynamically expressed. Mol Cell. 2015;58:870–85. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lasda E, Parker R. Circular RNAs: diversity of form and function. RNA. 2014;20:1829–42. doi: 10.1261/rna.047126.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salzman J. Circular RNA expression: its potential regulation and function. Trends Genet. 2016;32:309–16. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghosal S, Das S, Sen R, Basak P, Chakrabarti J. Circ2Traits: a comprehensive database for circular RNA potentially associated with disease and traits. Front Genet. 2013;4:283. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2013.00283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumar L, Shamsuzzama, Haque R, Baghel T, Nazir A. Circular RNAs: the emerging class of non-coding RNAs and their potential role in human neurodegenerative diseases. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54:7224–34. doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-0213-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boeckel JN, Jaé N, Heumüller AW, Chen W, Boon RA, Stellos K. et al. Identification and characterization of hypoxia-regulated endothelial circular RNA. Circ Res. 2015;117:884–90. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peng L, Chen GL, Zhu ZX, Shen ZY, Du CX, Zang RJ. et al. Circular RNA ZNF609 functions as a competitive endogenous RNA to regulate AKT3 expression by sponging miR-150-5p in Hirschsprung's disease. Oncotarget. 2017;8:808–18. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Legnini I, Di-Timoteo G, Rossi F, Morlando M, Briganti F, Sthandier O. et al. Circ-ZNF609 is a circular RNA that can be translated and functions in myogenesis. Mol Cell. 2017;66:22–37. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu C, Yao MD, Li CP, Shan K, Yang H, Wang JJ. et al. Silencing of circular RNA-ZNF609 ameliorates vascular endothelial dysfunction. Theranostics. 2017;7:2863–77. doi: 10.7150/thno.19353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carmeliet P. Blood vessels and nerves: common signals, pathways and diseases. Nat Rev Genet. 2003;4:710–20. doi: 10.1038/nrg1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yao J, Wang XQ, Li YJ, Shan K, Yang H, Yao MD. et al. Long non-coding RNA MALAT1 regulates retinal neurodegeneration through CREB signaling. EMBO Mol Med. 2016;8:346–62. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201505725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 25.Urcola JH, Hernández M, Vecino E. Three experimental glaucoma models in rats: comparison of the effects of intraocular pressure elevation on retinal ganglion cell size and death. Exp Eye Res. 2006;83:429–37. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2006.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen HH, Wei X, Cho KS, Chen GC, Sappington R, Calkins DJ. et al. Optic neuropathy due to microbead-induced elevated intraocular pressure in the mouse. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:36–44. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-5115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quigley HA. Neuronal death in glaucoma. Prog Retin Eye Res. 1999;18:39–57. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(98)00014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weinreb RN, Aung T, Medeiros FA. The pathophysiology and treatment of glaucoma: a review. JAMA. 2014;311:1901–11. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nishino J, Yamashita K, Hashiguchi H, Fujii H, Shimazaki T, Hamada H. Meteorin: a secreted protein that regulates glial cell differentiation and promotes axonal extension. EMBO J. 2004;23:1998–2008. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee HS, Han J, Lee SH, Park JA, Kim KW. Meteorin promotes the formation of GFAP-positive glia via activation of the Jak-STAT3 pathway. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:1959–68. doi: 10.1242/jcs.063784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chang EE, Goldberg JL. Glaucoma 2.0: neuroprotection, neuroregeneration, neuroenhancement. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:979–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tezel G. The role of glia, mitochondria, and the immune system in glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:1001–12. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang X, Tay SSW, Ng YK. An immunohistochemical study of neuronal and glial cell reactions in retinae of rats with experimental glaucoma. Exp Brain Res. 2000;132:476–84. doi: 10.1007/s002210000360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martin KRG, Levkovitch-Verbin H, Valenta D, Baumrind L, Pease ME, Quigley HA. Retinal glutamate transporter changes in experimental glaucoma and after optic nerve transection in the rat. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:2236–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tezel G, Wax MB. Increased production of tumor necrosis factor-ɑ by glial cells exposed to simulated ischemia or elevated hydrostatic pressure induces apoptosis in cocultured retinal ganglion cells. J Neurosci. 2000;20:8693–700. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-23-08693.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fruhbeis C, Frohlich D, Kramer-Albers EM. Emerging roles of exosomes in neuron-glia communication. Front Physiol. 2012;3:119. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salmina AB. Neuron-glia interactions as therapeutic targets in neurodegeneration. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;16:485–502. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-0988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shan K, Liu C, Liu BH, Chen X, Dong R, Liu X. et al. Circular noncoding RNA HIPK3 mediates retinal vascular dysfunction in diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2017;136:1629–42. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.029004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park JA, Lee HS, Ko KJ, Park SY, Kim JH, Choe G. et al. Meteorin regulates angiogenesis at the gliovascular interface. Glia. 2008;56:247–58. doi: 10.1002/glia.20600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary methods and figures.