Abstract

BACKGROUND & AIMS

It is not clear whether symptoms alone can be used to estimate the biologic activity of eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). We aimed to evaluate whether symptoms can be used to identify patients with endoscopic and histologic features of remission.

METHODS

Between April 2011 and June 2014, we performed a prospective, observational study and recruited 269 consecutive adults with EoE (67% male; median age, 39 years old) in Switzerland and the United States. Patients first completed the validated symptom-based EoE activity index patient-reported outcome instrument and then underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy with esophageal biopsy collection. Endoscopic and histologic findings were evaluated with a validated grading system and standardized instrument, respectively. Clinical remission was defined as symptom score <20 (range, 0 100); histologic remission was defined as a peak count of <20 eosinophils/ mm2 in a high-power field (corresponds to approximately <5 eosinophils/median high-power field); and endoscopic remission as absence of white exudates, moderate or severe rings, strictures, or combination of furrows and edema. We used receiver operating characteristic analysis to determine the best symptom score cutoff values for detection of remission.

RESULTS

Of the study subjects, 111 were in clinical remission (41.3%), 79 were in endoscopic remission (29.7%), and 75 were in histologic remission (27.9%). When the symptom score was used as a continuous variable, patients in endoscopic, histologic, and combined (endoscopic and histologic remission) remission were detected with area under the curve values of 0.67, 0.60, and 0.67, respectively. A symptom score of 20 identified patients in endoscopic remission with 65.1% accuracy and histologic remission with 62.1% accuracy; a symptom score of 15 identified patients with both types of remission with 67.7% accuracy.

CONCLUSIONS

In patients with EoE, endoscopic or histologic remission can be identified with only modest accuracy based on symptoms alone. At any given time, physicians cannot rely on lack of symptoms to make assumptions about lack of biologic disease activity in adults with EoE. ClinicalTrials.gov, Number: NCT00939263.

Keywords: EEsAI, Remission, Endoscopic Grading, Disease Monitoring

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) has been defined recently by an expert group as “a chronic, immune/antigen-mediated, esophageal disease characterized clinically by symptoms related to esophageal dysfunction and histologically by eosinophil-predominant inflammation.”1,2 Dysphagia is the leading EoE symptom in adult patients, but swallowing-associated pain and heartburn not responding to acid-suppressive medication can also occur.1,2 In Europe and the United States, a steady increase in EoE incidence and/or prevalence has been observed during the past 2 decades with a current prevalence of about 1/2,000 inhabitants.3–10

Despite the urgent need for EoE-specific therapies, to date, no such therapy has been approved by regulatory agencies, including the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency. There are 2 major hurdles in the way of seeking regulatory approval for EoE-specific therapies: first, standardized and validated instruments for reliable assessment of disease activity have been lacking for a long time and, second, there is an ongoing debate among different stakeholders regarding the choice of clinically relevant end points for use in clinical trials and natural history studies.11,12

Recently, considerable progress has been made toward developing and validating instruments for standardized disease activity assessment. Among others, the EoE endoscopic reference score, developed by Hirano et al, for grading the severity of distinct EoE-associated endoscopic features (edema, rings, exudates, furrows, and strictures) and the eosinophilic esophagitis activity index (EEsAI) patient-reported outcome (PRO) instrument for assessing clinical activity in adult patients, are now available for use in various studies.13,14

A dissociation between EoE symptom severity and histologic activity was documented in some, but not other studies.15–18 This leaves clinicians with uncertainty as to the elements upon which their therapeutic decisions should be based. Specifically, it is currently unknown whether physicians can rely solely on EoE-related symptoms when estimating the severity of endoscopic and histologic activity in a given patient.

The purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between clinical activity and biologic activity (endoscopy, histology) of EoE. Specifically, we aimed to examine the ability of the EEsAI PRO score to detect endoscopic and histologic remission in adult EoE patients. We also aimed to examine whether the previous EoE-specific treatment impacts the relationship between clinical and biologic EoE activity, and, in so doing, alters the ability of the EEsAI PRO score to detect biologic remission. This study may help to elucidate whether treatment decisions can be based solely on symptoms, or whether the biologic findings obtained during more invasive procedures, such as esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) with biopsy sampling, should also be taken into consideration.

Methods

Study Population

The study was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00939263) and approved by local institutional review boards and ethics committees. All authors had access to the study data and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Adult EoE patients (≥17 years of age) were consecutively recruited in 1 ambulatory care clinic and 5 hospitals in Switzerland and the United States between April 2011 and June 2014. All patients were treated by 6 gastroenterologists (AMS, JA, ED, NG, IH, and AS) specializing in EoE (each gastroenterologist has treated >50 EoE patients and performed >1000 EGDs). Patients provided written informed consent for participation in the study. All patients in need of an EGD for initial diagnosis, for confirming a suspected diagnosis, or for monitoring previously diagnosed EoE were invited to participate in the study. Patients were diagnosed by investigators according to standardized criteria.1,2 EoE patients with concomitant gastro-esophageal reflux disease were also included, provided that they fulfilled the following criteria: they were on continued proton-pump inhibitor therapy at the time of EGD; they had no symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease; and they had no evidence of acute reflux-related lesions. Before undergoing EGD, patients completed the EEsAI PRO instrument (in paper form).14

Assessment of Symptoms and Behavioral Adaptations to Living With Dysphagia

Development and validation of the EEsAI PRO instrument has been described recently.14 The EEsAI PRO instrument was developed in accordance with the US Food and Drug Administration guidelines.19,20 The instrument queries the following symptoms and behavioral adaptations to living with dysphagia recalled during a 7-day period: frequency of trouble swallowing, duration of trouble swallowing, thoracic pain when swallowing, trouble swallowing caused by foods of different consistencies, and behavioral adaptations to living with dysphagia, including avoidance; modification; and slow eating.14 The EEsAI PRO score ranges from 0 to 100 points.

Assessment of Eosinophilic Esophagitis Associated Endoscopic and Histologic Findings

During EGD, at least 4 biopsies from the proximal and 4 biopsies from the distal esophagus were obtained. For this study, we defined “distal” esophagus as the section of the esophagus 5 cm above the gastroesophageal junction and “proximal” esophagus as the section spanning the top half of the esophagus. Assessment of severity of EoE-associated endoscopic findings, such as edema, rings, exudates, furrows, and stricture(s) in the proximal and distal esophagus, was carried out by the treating physician in accordance with the EoE Endoscopic Reference Score classification and grading system.13 For the purposes of this study, white exudates, furrows, and edema were considered to represent endoscopic features associated with acute inflammation, and fixed rings and strictures were considered to represent features associated with chronic inflammation.13,21

Histologic evaluation of esophageal biopsies was performed by the local center pathologist with expertise in EoE. Five-micrometer sections were cut from paraffin blocks and then stained with H&E for examination by light microscopy. At least 5 levels of every esophageal biopsy specimen were surveyed, and the eosinophils in the most densely infiltrated area were counted under high-power examination (magnification 400×). The following features were recorded: size of high-power field (hpf [in mm2]), quality of sample orientation, percentage of the hpf covered by the tissue, peak number of eosinophils/hpf, distribution of eosinophils in an hpf, distribution of inflammation, presence of abscesses, basal layer enlargement, and lamina propria fibrosis.

Definitions of Endoscopic and Histologic Remission

We used the following definitions of endoscopic remission: Endoscopic inflammatory remission

absence of white exudates

furrows and edema may be present, but not in combination Endoscopic fibrotic remission

absence of moderate and severe rings

absence of strictures

Total endoscopic remission (inflammatory and fibrotic remission):

absence of white exudates

furrows and edema may be present but not in combination

absence of moderate and severe rings

absence of strictures

We used the following definitions of histologic remission: peak count of <20 eosinophils/mm2 of hpf and peak count of <60 eosinophils/mm2 of hpf. The data on peak eosinophil counts are presented as per mm2.22 The rationale for the definitions of histologic remission was as follows: median hpf size was 0.26 mm2 (interquartile range, 0.26 0.307 mm2; range, 0.204 0.545 mm2). Therefore, <20 eosinophils/mm 2 and <60 eosinophils/mm2 correspond to approximately <5 eosinophils/ median hpf and <15 eosinophils/median hpf, respectively.

We defined “deep remission” as the combination of endoscopic inflammatory and fibrotic remission, as well as histologic remission (peak eosinophil count <20/mm2 of hpf).

Data Handling and Statistical Analysis

The investigators at various centers sent the completed instruments to the data center at the Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine (University of Bern, Switzerland). Two researchers (ES, NH) double-entered the data into an EpiData database (version 3.1, EpiData Association, Odense, Denmark). The original records were checked to resolve any discrepancies. The study dataset was imported into Stata (version 13, Stata-Corp, College Station, TX) for analysis.

Descriptive results are presented as frequencies and corresponding percentages of the group total or median and interquartile range. To obtain the severity of the EoE-associated endoscopic and histologic findings for the esophagus overall, the most severe category for a given finding identified in proximal and distal esophagus was chosen. If data on severity of a given finding in one part of the esophagus were missing, then severity of that finding for another part of the esophagus was chosen as the one representing severity of that finding for the esophagus overall.

We performed several analyses in order to evaluate the accuracy of distinct EEsAI PRO values to detect endoscopic or histologic remission. First, we calculated the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and diagnostic accuracy of distinct EEsAI PRO score values to detect endoscopic and histologic remission at all possible EEsAI PRO values. The diagnostic accuracy is expressed as a proportion of the correctly classified subjects (true positive and true negative) among all subjects (true and false positive as well as true and false negative). Second, to determine the optimal cutoff value of the EEsAI PRO score for detecting endoscopic or histologic remission, we constructed receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curves. The ROC curve is a plot of the true-positive rate (sensitivity) vs the false-positive rate (1 – specificity) for the different possible cutoff values of a diagnostic test. The closer the curve follows the left-hand border and the top border of the ROC space, the more accurate the diagnostic test is.23 Therefore, the optimal cutoff value is the highest PRO score, which sits closest (Euclidean distance) to the top-left corner of the ROC space. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) was calculated from fitting logistic regression models (for each remission type) with the EEsAI PRO score as a continuous variable. A perfect test for discrimination between individuals with and without a given outcome has an AUC of 1.0, and a test that discriminates between these individuals with and without this outcome no better than chance has an AUC of 0.50. To examine whether the association between the EEsAI PRO score and the remission depends is modified by previous treatments (esophageal dilation, hypoallergenic diet, or swallowed topical corticosteroids), interaction tests between the EEsAI PRO score and different treatments were performed. The ROC curve analysis was repeated for treatment subgroups, if the interaction test with the EEsAI PRO score proved significant (P < .05).

Results

Patient Characteristics

A total of 269 adult patients with previously diagnosed EoE according to the established criteria were prospectively included into the study.1 Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. One hundred and fifty-nine patients (59.1%) had EoE symptom onset of >5 years before being recruited into the study. At the time of the study, asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis, eczema, and food allergies were self-reported by 97 patients (36.1%), 163 patients (60.6%), 52 patients (19.3%), and 113 patients (42.0%), respectively. Gastroesophageal reflux disease was diagnosed in 64 patients (23.8%). In the last 12 months before their participation in this study, 141 patients (52.4%), 37 patients (13.8%), and 53 patients (19.7%) had been treated for EoE with swallowed topical corticosteroids, hypoallergenic diets, and esophageal dilation, respectively.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics, Comorbidities, and Treatments

| Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Patients, N | 269 |

| Males | 180 (66.9) |

| Age at inclusion, median (IQR), range, y | 39.2 (30 47), 18 80 |

| EEsAI PRO score, median (IQR), range | 27 (12 42), 0 94 |

| Ethnicity | |

| White | 259 (96.3) |

| Non-white | 10 (3.7) |

| Education | |

| Compulsory schooling | 4 (1.5) |

| Vocational training | 69 (25.7) |

| Upper secondary education | 119 (44.2) |

| University education | 77 (28.6) |

| EoE symptoms onset | |

| <1 mo ago to 11 mo ago | 12 (4.5) |

| 1 to 5 y ago | 98 (36.4) |

| >5 y ago | 159 (59.1) |

| Atopic diseases/allergiesa ever in life | 206 (76.6) |

| Asthma | 97 (36.1) |

| Rhinoconjunctivitis | 163 (60.6) |

| Eczema | 52 (19.3) |

| Food allergy | 113 (42.0) |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 64 (23.8) |

| Clinically | 3 (4.7) |

| Endoscopically | 6 (9.4) |

| Based on pH-metric studies | 2 (3.1) |

| Clinically and endoscopically | 5 (7.8) |

| Concomitant medications in the past 7 d | |

| Proton-pump inhibitors | 121 (45.0) |

| Histamine antagonists (H2-receptor) | 7 (2.6) |

| Histamine antagonists (H1-receptor) | 42 (15.6) |

| Inhaled corticosteroids for asthma | 8 (3.0) |

| b2-adrenergic agonists for asthma | 23 (8.6) |

| Leukotriene receptor antagonists for asthma | 5 (1.9) |

| EoE-specific treatments in the last 12 mo | 190 (70.6) |

| Hypoallergenic diets in last 90 d | 37 (13.8) |

| Swallowed topical corticosteroids in last 90 d | 141 (52.4) |

| Esophageal dilation in last 12 mo | 53 (19.7) |

NOTE. Values are n (%) unless otherwise noted. IQR, interquartile range.

Patients self-reported lifetime (ever in life) atopies by answering the following item: “Have you ever been told by a doctor or another health professional that you had asthma/ allergy-related nose problem/eczema/food allergy?”

Eosinophilic Esophagitis Associated Endoscopic and Histologic Features

The EoE-associated endoscopic and histologic findings in proximal and distal esophagus, as well as for “esophagus overall,” are shown in Supplementary Table 1. Endoscopic findings were graded in accordance with the EoE endoscopic reference score.13 The frequency of distinct endoscopic findings was similar when the proximal esophagus was compared with the distal esophagus. If esophagus overall was examined, the following frequencies of endoscopic features were observed: exudates in 91 patients (33.8%), rings in 195 patients (72.5%), edema in 155 patients (57.6%), and strictures in 90 patients (33.5%).

The prevalence of distinct histologic findings was similar when the distal esophagus was compared with the proximal esophagus. Median peak eosinophil count was 92 per mm2 of hpf (interquartile range, 14–260; range, 0–1293 peak eosinophils/mm2). Eosinophilic abscesses were observed in 53 patients (19.7%).

Relationship Between Clinical, Endoscopic, and Histologic Activity

The proportion of patients with distinct EEsAI PRO scores, as well as endoscopic inflammatory, endoscopic fibrotic, total endoscopic, histologic, and deep remission at the time of inclusion in the study is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Proportion of Patients in Clinical (Using 3 Different EEsAI PRO Score Cutoff Values), Endoscopic, and Histologic Remission

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Patients with certain symptom score OR in endoscopic OR histologic remission | ||

| EEsAI PRO score <30 points | 162 | 60.2 |

| EEsAI PRO score <25 points | 112 | 41.6 |

| EEsAI PRO score <20 points | 111 | 41.3 |

| Endoscopic inflammatory remission | 117 | 43.5 |

| Endoscopic fibrotic remission | 148 | 55.0 |

| Total endoscopic remission | 79 | 29.4 |

| Histologic remission (peak count of <20 eosinophils/mm2) | 75 | 27.9 |

| Patients with certain symptom score AND in endoscopic remission | ||

| EEsAI PRO score <30 AND in endoscopic inflammatory remission | 85/162 | 52.5 |

| EEsAI PRO score <30 AND in endoscopic fibrotic remission | 104/162 | 64.2 |

| EEsAI PRO score <30 AND in total endoscopic remission | 63/162 | 38.9 |

| EEsAI PRO score <25 AND in endoscopic inflammatory remission | 63/112 | 56.3 |

| EEsAI PRO score <25 AND in endoscopic fibrotic remission | 75/112 | 67.0 |

| EEsAI PRO score <25 AND in total endoscopic remission | 48/112 | 42.9 |

| EEsAI PRO score <20 AND in endoscopic inflammatory remission | 63/111 | 56.8 |

| EEsAI PRO score <20 AND in endoscopic fibrotic remission | 75/111 | 67.6 |

| EEsAI PRO score <20 AND in total endoscopic remission | 48/111 | 43.2 |

| Patients with certain symptom score AND in histologic remission | ||

| EEsAI PRO score <30 AND in histologic remission (<20 eosinophils/mm2) | 51/162 | 31.5 |

| EEsAI PRO score <25 AND in histologic remission (<20 eosinophils/mm2) | 42/112 | 37.5 |

| EEsAI PRO score <20 AND in histologic remission (<20 eosinophils/mm2) | 42/111 | 37.8 |

| Patients with certain symptom score AND in endoscopic AND histologic remission | ||

| EEsAI PRO score <30 AND in total endoscopic AND histologic remission | 32/162 | 19.8 |

| EEsAI PRO score <25 AND in total endoscopic AND histologic remission | 25/112 | 22.3 |

| EEsAI PRO score <20 AND in total endoscopic AND histologic remission | 25/111 | 22.5 |

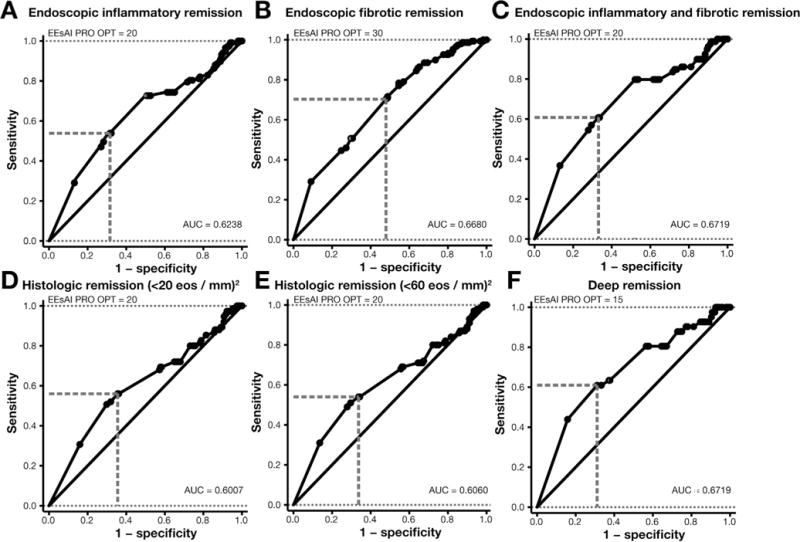

Test accuracy of distinct EEsAI PRO score cutoff values to detect endoscopic inflammatory, endoscopic fibrotic, and total endoscopic remission is shown in Table 3. Results of the ROC curve analysis are shown in Figure 1 for endoscopic inflammatory remission (Figure 1A), endoscopic fibrotic remission (Figure 1B), and total endoscopic remission (Figure 1C). The AUC was 0.6719 for detection of total endoscopic remission when compared with 0.6680 and 0.6238 for detection of endoscopic fibrotic and endoscopic inflammatory remission, respectively. A PRO score of 20 identified patients in endoscopic inflammatory remission with 62.1% accuracy and in total endoscopic remission with 65.1% accuracy; a score of 30 identified patients in endoscopic fibrotic remission with 62.1% accuracy.

Table 3.

Accuracy of Patient-Reported Clinical Symptoms (Assessed Using EEsAI PRO Score) to Detect Endoscopic Remission

| EEsAI PRO score cutoff | Cumulative remissions,a n (%) | Cumulative frequency,b n (%) | PPV, % | NPV, % | Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % | Accuracy, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endoscopic inflammatory remission | |||||||

| 15 | 55/96 (57.3) | 96/269 (35.7) | 57.3 | 64.2 | 47.0 | 73.0 | 61.7 |

| 20 | 63/111 (56.8) | 111/269 (41.3) | 56.8 | 65.8 | 53.8 | 68.4 | 62.1 |

| 25 | 63/112 (56.3) | 112/269 (41.6) | 56.3 | 65.6 | 53.8 | 67.8 | 61.7 |

| 30 | 85/162 (52.5) | 162/269 (60.2) | 52.5 | 70.1 | 72.6 | 49.3 | 59.5 |

| 35 | 87/180 (48.3) | 180/269 (66.9) | 48.3 | 66.3 | 74.4 | 38.8 | 54.3 |

| Endoscopic fibrotic remission | |||||||

| 15 | 66/96 (68.8) | 96/269 (35.7) | 68.8 | 52.6 | 44.6 | 75.2 | 58.4 |

| 20 | 75/111 (67.6) | 111/269 (41.3) | 67.6 | 53.8 | 50.7 | 70.2 | 59.5 |

| 25 | 75/112 (67.0) | 112/269 (41.6) | 67.0 | 53.5 | 50.7 | 69.4 | 59.1 |

| 30 | 104/162 (64.2) | 162/269 (60.2) | 64.2 | 58.9 | 70.3 | 52.1 | 62.1 |

| 35 | 114/180 (63.3) | 180/269 (66.9) | 63.3 | 61.8 | 77.0 | 45.5 | 62.8 |

| Total endoscopic remission (inflammatory and fibrotic) | |||||||

| 15 | 43/96 (44.8) | 96/269 (35.7) | 44.8 | 79.2 | 54.4 | 72.1 | 66.9 |

| 20 | 48/111 (43.2) | 111/269 (41.3) | 43.2 | 80.4 | 60.8 | 66.8 | 65.1 |

| 25 | 48/112 (42.9) | 112/269 (41.6) | 42.9 | 80.3 | 60.8 | 66.3 | 64.7 |

| 30 | 63/162 (38.9) | 162/269 (60.2) | 38.9 | 85.0 | 79.7 | 47.9 | 57.2 |

| 35 | 63/180 (35.0) | 180/269 (66.9) | 35.0 | 82.0 | 79.7 | 38.4 | 50.6 |

NOTE. Data for 5 different cutoff values of EEsAI PRO score are shown. NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value.

Number of patients in endoscopic remission for a given EEsAI PRO score cutoff value.

Number of patients with a given EEsAI PRO score below the cutoff value.

Figure 1.

Receiver operator curve analysis was carried out to determine the best EEsAI PRO score cutoff value to detect endoscopic inflammatory remission (A), endoscopic fibrotic remission (B), endoscopic inflammatory and fibrotic remission (C), histologic remission defined as peak eosinophil count of <20/mm2 (D), histologic remission defined as peak eosinophil count of <60/mm2 (E), and deep remission defined as the combination of endoscopic inflammatory and fibrotic remission as well as histologic remission (peak eosinophil count of <20/mm2) (F). eos, eosinophils; OPT, optimal.

We evaluated the test accuracy of distinct EEsAI PRO score cutoff values to detect histologic remission. These results are shown in Table 4. The results of ROC curve analysis are shown in Figure 1D and E. The AUC was 0.6007 and 0.6060 for detecting histologic remission defined as peak eosinophil count of <20/mm2 and <60/mm2 of hpf, respectively. A PRO score of 20 points identified patients in histologic remission of <20 eosinophils/mm2 of hpf with overall accuracy of 62.1% and in histologic remission of <60 eosinophils/mm2 of hpf with 61.7% accuracy.

Table 4.

Accuracy of Patient-Reported Clinical Symptoms (Assessed Using EEsAI PRO Score) to Detect Histologic Remission

| EEsAI PRO score cutoff | Cumulative remission,a n (%) | Cumulative frequency,b n (%) | PPV, % | NPV, % | Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % | Accuracy, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histologic remission: peak count of <20 eosinophils/mm2 | |||||||

| 15 | 38/96 (39.6) | 96/269 (35.7) | 39.6 | 78.6 | 50.7 | 70.1 | 64.7 |

| 20 | 42/111 (37.8) | 111/269 (41.3) | 37.8 | 79.1 | 56.0 | 64.4 | 62.1 |

| 25 | 42/112 (37.5) | 112/269 (41.6) | 37.5 | 79.0 | 56.0 | 63.9 | 61.7 |

| 30 | 51/162 (31.5) | 162/269 (60.2) | 31.5 | 77.6 | 68.0 | 42.8 | 49.8 |

| 35 | 54/180 (30.0) | 180/269 (66.9) | 30.0 | 76.4 | 72.0 | 35.1 | 45.4 |

| Histologic remission: peak count of <60 eosinophils/mm2 | |||||||

| 15 | 49/96 (51.0) | 96/269 (35.7) | 51.0 | 70.5 | 49.0 | 72.2 | 63.6 |

| 20 | 54/111 (48.6) | 111/269 (41.3) | 48.6 | 70.9 | 54.0 | 66.3 | 61.7 |

| 25 | 54/112 (48.2) | 112/269 (41.6) | 48.2 | 70.7 | 54.0 | 65.7 | 61.3 |

| 30 | 68/162 (42.0) | 162/269 (60.2) | 42.0 | 70.1 | 68.0 | 44.4 | 53.2 |

| 35 | 71/180 (39.4) | 180/269 (66.9) | 39.4 | 67.4 | 71.0 | 35.5 | 48.7 |

NOTE. Data for 5 different cutoff values of EEsAI PRO score are shown. NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value.

Number of patients in histologic remission for a given EEsAI PRO score cutoff value.

Number of patients with a given EEsAI PRO score below the cutoff value.

Lastly, we examined the diagnostic accuracy of distinct EEsAI PRO score cutoff values to detect deep remission (Table 5). The corresponding ROC curve with EEsAI PRO score as continuous variable for detection of deep remission is shown in Figure 1F. The AUC was 0.6719. An EEsAI PRO score of 15 points had an overall accuracy of 67.7% to detect patients in deep remission.

Table 5.

Accuracy of Patient-Reported Clinical Symptoms (Assessed Using EEsAI PRO Score) to Detect Deep Remissiona

| EEsAI PRO score cutoff | Cumulative remission,b n (%) | Cumulative frequency,c n (%) | PPV, % | NPV, % | Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % | Accuracy, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deep remission (total endoscopic and histologic remission) | |||||||

| 15 | 25/96 (26.0) | 96/269 (35.7) | 26.0 | 90.8 | 61.0 | 68.9 | 67.7 |

| 20 | 26/111 (23.4) | 111/269 (41.3) | 23.4 | 90.5 | 63.4 | 62.7 | 62.8 |

| 25 | 26/112 (23.2) | 112/269 (41.6) | 23.2 | 90.4 | 63.4 | 62.3 | 62.5 |

| 30 | 33/162 (20.4) | 162/269 (60.2) | 20.4 | 92.5 | 80.5 | 43.4 | 49.1 |

| 35 | 33/180 (18.3) | 180/269 (66.9) | 18.3 | 91.0 | 80.5 | 35.5 | 42.4 |

NOTE. Data for 5 different cutoff values of EEsAI PRO score are shown.

NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value.

Defined as endoscopic inflammatory and fibrotic remission in combination with histologic remission (defined as a peak eosinophil count <20/mm2).

Number of patients in deep remission for a given EEsAI PRO score cutoff value.

Number of patients with a given EEsAI PRO score below the cutoff value.

Impact of Treatment on the Relationships Among Clinical, Endoscopic, and Histologic Activity

We found that interaction terms between EEsAI PRO score and previous EoE-specific treatments were not significant for treatment with hypoallergenic diets and swallowed topical corticosteroids. However, a statistically significant interaction term (P = .0412) suggested that the relationship between EEsAI PRO score and total endoscopic remission changes, depending on whether a patient was treated with a dilation in the 12 months before inclusion. Therefore, we evaluated whether dilation influences the relationships among clinical, endoscopic, and histologic activity by first examining the frequency of the EoE-associated endoscopic and histologic findings in proximal and distal esophagus, as well as for esophagus overall (shown in Supplementary Table 2) in the patient group that underwent dilation in the last 12 months before inclusion in the study (n = 53) and in the patient group that did not undergo dilation (n = 213; dilation status of 3 patients was unknown). Patients that underwent dilation in the last 12 months before inclusion into the study were more likely to have strictures, moderate and severe rings, as well as white exudates and eosinophilic microabscesses when compared with patients that did not undergo dilation. The results of ROC curve analysis in patients stratified into groups based on absence or presence of dilation are shown in Supplementary Table 3. In the group of patients that underwent dilation, we found a good diagnostic accuracy for the EEsAI PRO instrument to detect patients in endoscopic fibrotic remission (AUC 0.768, optimal PRO value 25 points) and in deep remission (defined as endoscopic fibrotic and inflammatory as well as histologic remission) (AUC 0.863, optimal PRO value 25 points) (Supplementary Figure 1). In the nondilated patients, the AUC for all types of remission were similar to those observed when the entire study population was examined together.

Discussion

In this study, we examined the relationship between symptoms as measured by EEsAI PRO score and biologic findings in adults with EoE. We found that endoscopic and/ or histologic remission can be identified with only modest accuracy based on symptoms alone. Therefore, at any given time, physicians cannot rely on lack of symptoms to make assumptions about lack of biologic disease activity in adult EoE patients.

Accurate detection of endoscopic or histologic remission by the means of a symptom-based instrument would reduce the need to perform regular endoscopic and histologic follow-up examinations. This, in turn, would considerably reduce the burden of disease for patients and EGD-associated health care costs. We found that the overall accuracy of detecting endoscopic and histologic remission based on distinct EEsAI PRO score cutoff values was modest (AUC ranging between 0.6 and 0.7). At present, data on the accuracy of other EoE-specific symptom-based activity instruments to detect endoscopic and histologic remission are lacking. When comparing the accuracy of the EEsAI PRO instrument to clinically based instruments used in other conditions, such as Crohn’s disease, we found that the EEsAI PRO score (using a score of 20 points as a cutoff) was better at detecting endoscopic remission (accuracy 65%) in EoE patients when compared with detection of endoscopic remission by means of the Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI).24 Specifically, a CDAI score <100 points had an overall accuracy of 55% in detecting endoscopic remission, and a CDAI score of <150 points had an overall accuracy of 56% in detecting endoscopic remission.24 As of yet, no data on the accuracy of various clinical scores to detect histologic remission in Crohn’s disease patients have been published. This is related, in part, to the fact that no formally accepted definition of histologic remission exists for both EoE and Crohn’s disease. Given that the size of an hpf varied, we standardized the peak eosinophil count per mm2. We chose a cutoff value of <20 eosinophils/hpf to define histologic remission, which corresponds to a value of <5 eosinophils/ hpf for a median hpf size of 0.26 mm2. An EEsAI PRO score of 20 points had an overall accuracy of 62% to detect histologic remission.

Why is the test accuracy of detecting biologic remission based on the adult EEsAI PRO score only modest (AUC 0.6 0.7)? First, we found in a previous study that the perception of mild and moderate endoscopic or histologic alterations in adult EoE patients seems to be relatively poor.14 Only patients with severe endoscopic features had relevant symptoms.14 We made similar observations when we analyzed the relationship between patient quality of life (as assessed by an adult EoE quality of life instrument) and endoscopic and histologic alterations.25,26 Patients with mild or moderate endoscopic and histologic features had relatively good quality of life (low adult EoE quality of life instrument score). However, the quality of life score was considerably poorer in patients with severe endoscopic inflammatory and/or fibrotic alterations or histologic inflammation (eg, presence of microabscesses).25 These results together suggest that endoscopically and histologically mild disease does not cause any symptoms or else very mild symptoms to which patients become accustomed over time. These findings are corroborated by a long diagnostic delay observed in EoE patients.21 Second, symptoms in EoE patients are mainly generated by altered esophageal motility caused by the presence of eosinophil-predominant inflammation and/or subepithelial fibrous tissue deposition (esophageal remodeling) that decreases the esophageal compliance.27,28 Sampling 4 proximal and 4 distal esophageal biopsies has a very good accuracy (>95%) for detecting the degree of mucosal eosinophilic inflammation.29 However, consistently sampling subepithelial esophageal tissue with standard biopsy forceps might be quite difficult. Only 61% of all patients included into our study had subepithelial tissue that could be evaluated for presence of fibrosis. As such, our knowledge of processes occurring deeper in the esophageal wall and contributing to subtle stricture formation and loss of distensibility is limited. In other words, using biopsy sampling alone, we underestimate the degree of esophageal remodeling processes and inflammation that could potentially contribute to symptom generation. Indeed, upon histologic examination of specimens obtained from patients that underwent esophagectomy, an extensive lamina propria fibrosis contributing to increased wall thickness was observed.30,31 In addition, eosinophilic infiltration was observed not only in the mucosa, but throughout the esophageal wall as well, this infiltration penetrated the submucosa.30,31 In the future, technologies such as the Endolumenal Functional Lumen Imaging Probe, which allows assessment of esophageal diameter and esophageal compliance, will help physicians to better estimate the extent of esophageal remodeling and overall EoE activity beyond the endoscopic and histologic alterations.32 Given that untreated subclinical eosinophilic inflammation can lead to stricture formation (which represents the main risk factor for the food bolus impactions), we conclude that physicians should not only rely on patient-reported symptoms, but also on endoscopic and histologic findings when assessing disease severity in studies or during the clinical follow-up of adult EoE patients.21

When we examined the effect of different EoE-specific therapies on the relationship between EEsAI PRO score and various types of remission, we found that this relationship was not affected by treatment with hypoallergenic diets and swallowed topical corticosteroids in the 3 months before inclusion into the study. However, the relationship between EEsAI PRO score and the total endoscopic remission changes, depending on whether patients underwent dilation in the 12 months before inclusion or not. In the attempt to explain this phenomenon, we examined the frequency of various endoscopic fibrotic and inflammatory findings, such as mild and severe exudates, moderate and severe rings, as well as strictures in dilated and non-dilated patients. We found that patients that underwent dilation were actually more likely to have these findings when compared with patients that did not undergo dilation. As previously discussed, patients seem to perceive more extreme endoscopic findings. Therefore, over-representation of extreme findings in the group of patients that underwent dilation is the reason behind a good diagnostic accuracy of the EEsAI PRO score for detection of endoscopic fibrotic remission (and by extension total endoscopic remission and deep remission). However, this raises another important issue relating to the kind of effect that various EoE-specific treatments have on underlying disease biology and symptoms. Although treatment with hypoallergenic diets and swallowed topical corticosteroids impacts the underlying disease biology and, in so doing, leads to symptom improvement, treatment with dilation does not change underlying disease biology.33 However, dilation can lead to long-lasting improvement in symptoms. This disconnect between disease biology and symptoms might be another reason behind the perturbed relationship between EEsAI PRO score and remission in patients that underwent dilation.

Our study has strengths and some limitations as well. We evaluated the relationship between symptom severity on the one hand, and endoscopic and histologic activity on the other, using validated instruments for assessment of clinical and endoscopic activity in a well-defined, prospectively enrolled EoE population. However, the findings of our study should be interpreted with a number of considerations in mind. First, we did not evaluate the relationship between clinical activity and various novel tests, such as blood biomarkers (eg, blood eosinophil levels or serum levels of eosinophilic cationic protein), the esophageal string test, cytosponge, or the Endolumenal Functional Lumen Imaging Probe.32,34 36 Some of these might further enhance our ability to estimate EoE activity. Second, the EEsAI PRO instrument was designed specifically for use in adult patients; we do not know whether similar observations would also hold true in a pediatric population, where symptoms related to inflammation rather than fibrosis predominate.

In summary, given the imperfect concordance between patient-reported symptoms and endoscopic/histologic findings, physicians cannot rely on lack of symptoms to make assumptions about lack of biologic disease activity in adult EoE patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Members of the international EEsAI study group participating in data collection (in alphabetical order): Sami R. Achem (Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL), Amindra S. Arora (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN), Oral Alpan (O&O Alpan, LLC, Section on Immunopathogenesis, Fairfax), David Armstrong (McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada), Stephen E. Attwood (North Tyneside Hospital, North Shields, UK), Joseph H. Butterfield (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN), Michael D. Crowell (Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, AZ), Kenneth R. DeVault (Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL), Eric Drouin (CHU Sainte-Justine, Montreal, Canada), Benjamin Enav (Pediatric Gastroenterology of Northern Virginia), Felicity T. Enders (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN), David E. Fleischer (Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, AZ), Amy Foxx-Orenstein (Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, AZ), Dawn L. Francis (Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL), Gordon H. Guyatt (McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada), Lucinda A. Harris (Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, AZ), Amir F. Kagalwalla (Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago), Hirohito Kita (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN), Murli Krishna (Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL), James J. Lee (Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, AZ), John C. Lewis (Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, AZ), Kaiser Lim (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN), G. Richard Locke III (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN), Joseph A. Murray (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN), Cuong C. Nguyen (Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, AZ), Diana M. Orbelo (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN), Shabana F. Pasha (Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, AZ), Francisco C. Ramirez (Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, AZ), Javed Sheikh (Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles Medical Center, Los Angeles), Sarah B. Umar (Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, AZ), Catherine R. Weiler (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN), John M. Wo (Indiana University, Indianapolis), Tsung-Teh Wu (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN), Kathleen J. Yost (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN).

These authors disclose the following: Ekaterina Safroneeva received consulting fees from Aptalis Pharma, Inc, and Novartis, AG, Switzerland. Alex Straumann received consulting fees and/or speaker fees and/or research grants from Actelion, AG, Switzerland, AstraZeneca, AG, Switzerland, Aptalis Pharma, Inc, Dr Falk Pharma, GmbH, Germany, Glaxo Smith Kline, AG, Nestlé S. A., Switzerland, Novartis, AG, Switzerland, Pfizer, AG, and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Marcel Zwahlen received research grants from AstraZeneca, AG Switzerland, Aptalis Pharma, Inc, Dr Falk Pharma, GmbH, Germany, Glaxo Smith Kline, AG, and Nestlé S.A., Switzerland. Claudia E. Kuehni received research grants from AstraZeneca, AG, Switzerland, Aptalis Pharma, Inc, Dr Falk Pharma, GmbH, Germany, Glaxo Smith Kline, AG, and Nestlé S.A., Switzerland. Radoslaw Panczak received consulting fees from Aptalis Pharma Inc. Jeffrey A. Alexander received research grants and/or consulting fees from Merck & Co., Inc, Meritage Pharma, Inc, and Aptalis Pharma, Inc and receives royalties for commercial use of the Mayo Dysphagia Questionnaire-30 Day. He also has financial interest in Meritage Pharma, Inc. Evan S. Dellon received research grants from AstraZeneca, AG, and Meritage Pharma, Inc. He has received consulting fees from Aptalis Pharma, Inc, Novartis, AG, Receptos, Inc, and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Nirmala Gonsalves has received consulting fees from Nutricia North America, Inc. Ikuo Hirano received research grants from Meritage Pharma, Inc, and consulting fees from Aptalis Pharma, Inc, Meritage Pharma, Inc, and Receptos, Inc. John Leung received research grants from Meritage Pharma, Inc. Margaret H. Collins received consulting fees from Aptalis Pharma, Inc, Biogen Idec, Meritage Pharma, Inc, Novartis, AG, Receptos, Inc and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc and has received contractual funds from Meritage Pharma, Inc, Receptos, Inc and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Yvonne Romero collaborates on projects supported by Aptalis Pharma, Inc and Meritage Pharma, Inc and receives royalties for commercial use of the Mayo Dysphagia Questionnaire-30 Day. Glenn T. Furuta received consulting fees from Pfizer, Inc, Meritage Pharma, Inc, Knopp and Biosciences, LLC, and royalties from UpToDate, Inc. He is also a founder of EnteroTrack, LLC. Sandeep K. Gupta received consulting fees and/or speaker fees from Abbott Laboratories, Nestlé S.A., QOL, Receptos, Inc, and Meritage Pharma, Inc. Seema S. Aceves is a co-inventor of oral viscous budesonide (OVB, patent held by UCSD), received royalties for OVB from Meritage Pharma, Inc, owns stocks in Meritage Pharma, Inc, and received consulting fees from Receptos, Inc and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Alain M. Schoepfer received consulting fees and/or speaker fees and/or research grants from AstraZeneca, AG, Switzerland, Aptalis Pharma, Inc, Dr Falk Pharma, GmbH, Germany, Glaxo Smith Kline, AG, Nestlé S.A., Switzerland, and Receptos, Inc.

Funding

This work was supported by the following grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant no. 32003B_135665/1 to AMS, AS, CK, and MZ and 32003B_160115/1 to AMS), AstraZeneca AG, Switzerland, Aptalis Pharma Inc, Dr Falk Pharma GmbH, Germany, Glaxo Smith Kline AG, Nestlé S.A., Switzerland, Receptos Inc, Regeneron Inc, and The International Gastrointestinal Eosinophil Researchers (TIGER).

Abbreviations used in this paper

- AUC

area under the curve

- CDAI

Crohn’s Disease Activity Index

- EEsAI

Eosinophilic Esophagitis Activity Index

- EoE

eosinophilic esophagitis

- EGD

esophagogastroduodenoscopy

- hpf

high-power field

- PRO

patient-reported outcome

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic

Footnotes

Supplementary Material

Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of Gastroenterology at www.gastrojournal.org, and at http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2015.11.004.

Author names in bold designate shared co-first authorship.

Conflicts of interest

The remaining authors disclose no conflicts.

References

- 1.Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:3–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Collins MH, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adults: a systematic review and consensus recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1342–1363. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hruz P, Straumann A, Bussmann C, et al. Escalating incidence and prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis: a 20-year prospective, population-based study in Olten County, Switzerland. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:1349–1350. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arias A, Lucendo AJ. Prevalence of eosinophilic oesophagitis in adult patients in a central region of Spain. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:208–212. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32835a4c95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Rhijn BD, Verheij J, Smout AJ, et al. Rapidly increasing incidence of eosinophilic esophagitis in a large cohort. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;25:47–52. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeBrosse CW, Collins MH, Buckmeier Butz BK, et al. Identification, epidemiology, and chronicity of pediatric esophageal eosinophilia, 1982–1999. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prasad GA, Alexander JA, Schleck CD, et al. Epidemiology of eosinophilic esophagitis over three decades in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1055–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Straumann A, Simon HU. Eosinophilic esophagitis: escalating epidemiology? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:418–419. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spergel JM, Book WM, Mays E, et al. Variation in prevalence, diagnostic criteria, and initial management options for eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases in the United States. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;52:300–306. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181eb5a9f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Noel RJ, Putnam PE, Rothenberg ME. Eosinophilic esophagitis. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:940–941. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200408263510924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rothenberg ME, Aceves S, Bonis PA, et al. Working with the US Food and Drug Administration: progress and timelines in understanding and treating patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:617–619. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.06.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fiorentino R, Liu G, Pariser AG, et al. Cross-sector sponsorship of research in eosinophilic esophagitis: a collaborative model for rational drug development in rare diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:613–616. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirano I, Moy N, Heckman MG, et al. Endoscopic assessment of the oesophageal features of eosinophilic esophagitis: validation of a novel classification and grading system. Gut. 2013;62:489–495. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schoepfer A, Straumann A, Panczak R, et al. Development and validation of a symptom-based activity index for adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:1255–1266. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alexander JA, Jung KW, Arora AS, et al. Swallowed fluticasone improves histologic but not symptomatic response of adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:742–749. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pentiuk S, Putnam PE, Collins MH, et al. Dissociation between symptoms and histological severity in pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48:152–160. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31817f0197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Straumann A, Conus S, Degen L, et al. Budesonide is effective in adolescent and adult patients with active eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1526–1537. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dohil R, Newbury R, Fox L, et al. Oral viscous budesonide is effective in children with eosinophilic esophagitis in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:418–429. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patrick DL, Burke LB, Powers JH, et al. Patient-reported outcomes to support medical product labeling claims: FDA Perspective. Value Health. 2007;10(Suppl 2):S125–S137. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Erickson P, Willke R, Burke L. A concept taxonomy and an instrument hierarchy: tools for establishing and evaluating the conceptual framework of a patient-reported outcome (PRO) instrument as applied to product labeling claims. Value Health. 2009;12:1158–1167. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2009.00609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schoepfer AM, Safroneeva E, Bussmann C, et al. Delay in diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis increases risk for stricture formation in a time-dependent manner. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:1230–1236. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dellon ES, Aderoju A, Woosley JT, et al. Variability in diagnostic criteria for eosinophilic esophagitis: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1200–1213. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Griner PF, Mayewski RJ, Mushlin AI, et al. Selection and interpretation of diagnostic tests and procedures. Principles and applications. Ann Intern Med. 1981;94:557–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peyrin-Biroulet L, Reinisch W, Colombel JF, et al. Clinical disease activity, C-reactive protein normalisation, and mucosal healing in the SONIC trial. Gut. 2014;63:88–95. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-304984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Safroneeva E, Coslovsky M, Kuehni CE, et al. Determinants of quality of life in adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;142:1451–1459. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taft TH, Kern E, Kwiatek MA, et al. The adult eosinophilic esophagitis quality of life questionnaire: a new measure of health-related quality of life. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:790–798. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rieder F, Nonevski I, Ma J, et al. T-helper 2 cytokines, transforming growth factor b1, and eosinophil products induce fibrogenesis and alter muscle motility in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1266–1277. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.01.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roman S, Hirano I, Kwiatek MA, et al. Manometric features of eosinophilic esophagitis in esophageal pressure topography. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23:208–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01633.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gonsalves N, Policarpio-Nicolas M, Zhang Q, et al. Histopathologic variability and endoscopic correlates in adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fontillon M, Lucendo AJ. Transmural eosinophilic infiltration and fibrosis in a patient with non-traumatic Boerhaave’s syndrome due to eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1762. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clayton F, Fang JC, Gleich GJ, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in adults is associated with IgG4 and not mediated by IgE. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:602–609. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kwiatek MA, Hirano I, Kahrilas PJ, et al. Mechanical properties of the esophagus in eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:82–90. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schoepfer AM, Gonsalves N, Bussmann C, et al. Esophageal dilation in eosinophilic esophagitis: effectiveness, safety, and impact on the underlying inflammation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1062–1070. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dellon ES, Rusin S, Gebhardt JH, et al. Utility of a noninvasive serum biomarker panel for diagnosis and monitoring of eosinophilic esophagitis: a prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:821–827. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katzka DA, Geno DM, Ravi A, et al. Accuracy, safety and tolerability of tissue collection by cytosponge vs endoscopy for evaluation of eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Furuta GT, Kagalwalla AF, Lee JJ, et al. The oesophageal string test: a novel, minimally invasive method measures mucosal inflammation in eosinophilic esophagitis. Gut. 2013;62:1395–1405. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.