Abstract

A 17-year-old woman, with a history of three operations on the upper gut in early life and intermittent diarrhoea, presented with a history of epistaxis and leg ecchymosis for the previous 3 months. Initial investigation revealed mild anaemia, low serum albumin, moderately elevated aminotransferases and an exceedingly prolonged prothrombin time (PT) which was promptly shortened to normal by intravenous vitamin K. Additional investigations revealed a grossly abnormal glucose hydrogen breath test, a dilated duodenum and deficiencies of vitamins A, D and E. Repeated courses of antimicrobial agents caused prompt but transient shortening of PT and eventually a duodenal–jejunal anastomosis was performed. Since then, up to 36 months later, the patient has been in good general health and PT has been consistently normal with no vitamin K supplementation. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth has previously been associated with several conditions but this is the first description of its association with vitamin K-responsive coagulopathy.

Keywords: malabsorption, vitamins and supplements

Background

The consequences of nutritional deficiencies, including those of fat-soluble vitamins, are the basis of the clinical presentation in many patients with malabsorption. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) is a well-known cause of malabsorption and malnutrition but vitamin K serum level is usually normal in patients with SIBO, even when malabsorption is conspicuous and serum levels of vitamins A, D and E are low.1 2 Accordingly, coagulopathy seems to be rare in SIBO.2 In addition, high prevalence of SIBO was found in patients with high warfarin dose requirements.3 The most widely current explanation for the lack of vitamin K deficiency in SIBO is the production of vitamin K2 (menaquinone) by luminal anaerobic bacteria whose population would be expanded.1 2 Also consistent with the notion of the importance of vitamin K production by luminal bacteria is the association of vitamin K deficiency with the use of broad-spectrum antibiotic.4 Here, we present a case of vitamin K-responsive coagulation disorder in a patient with a grossly dilated small bowel loop and well-characterised SIBO, and we believe that is the first description of this association in the literature.

Case presentation

A 17-year-old woman presented with a history of leg ecchymosis at sites of minor trauma and occasional epistaxis for 3 months. She had a medical history of two upper gut operations in the early neonatal life (first 12 days of life) for correction of jejunal atresia with resection of 30 cm of jejunum and restoration of bowel continuity by an end-to-end anastomosis. Another operation was performed 2 years later for correction of an upper jejunal stenosis. The patient also reported frequent bouts of diarrhoea from childhood. Physical examination revealed a thin (body mass index (BMI): 16.1 kg/m2) postpubertal woman with mild oedema in the lower left limb. There were no peripheral chronic liver disease stigmata and the abdominal examination was unrevealing, except for slight distension. Laboratory testing revealed mild anaemia (haemoglobin: 11.8 g/dL), a normal platelet count (183×109/L), a prolonged prothrombin time (PT) (65.5 s; INR - international normalized ratio: 6.06), moderately elevated serum alanine aminotransferase (170 U/L) and aspartate aminotransferase (157 U/L) and low serum albumin (3.04 g/dL). A barium follow-through performed 4 years before the bleeding symptoms revealed grossly dilated loops of proximal small bowel (figure 1).

Figure 1.

A barium follow-through performed 4 years before the bleeding symptoms. Grossly dilated loops of proximal small bowel can be seen.

Investigations

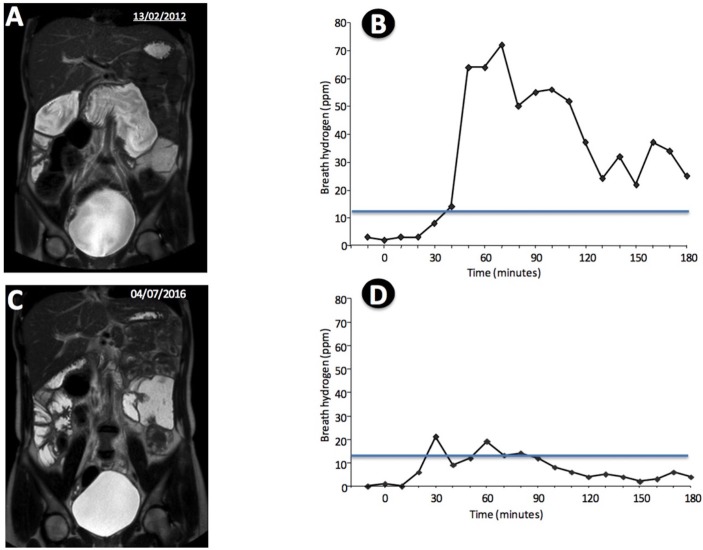

Additional laboratory studies carried out 24 hours later confirmed prolonged PT (74.0 s; INR: 8.01) which was shortened to normal range in a few hours after a single dose of vitamin K (2 mg intravenously). Serum alanine aminotransferase (241 U/L) and aspartate aminotransferase (182 U/L) levels were elevated, and blood levels of vitamin A (0.10 mg/L), 25-hydroxyvitamin D (16.5 ng/mL) and vitamin E (<0.5 mcg/mL) were low. Total and direct bilirubin levels were normal, and tests for HBsAg, anti-HBsAg, anti-HCV, IgA antigliadin and IgA antiendomysial were negative. MR enterography revealed a grossly dilated duodenum (figure 2A). This finding led us to investigate the possibility of SIBO, which was demonstrated by a markedly abnormal glucose breath test (figure 2B).

Figure 2.

(A) MR enterography revealed a grossly dilated duodenum; (B) glucose breath test showing an abnormal result; (C) MR enterography performed 36 months after side-to-side duodenal–jejunal anastomosis showing improvement of the small bowel dilation; (D) glucose breath test after side-to-side duodenal–jejunal anastomosis showing only slight abnormality.

Differential diagnosis

The finding of elevated aminotransferases might lead to the suspicion of liver disease as the cause of prolonged PT in this case but the absence of additional evidence of severe liver disease and the rapid and complete correction of the coagulopathy by parenteral vitamin K administration weakened this hypothesis. The coexistence of a stagnant upper small bowel, diarrhoea and clinical and laboratory evidence of malnutrition prompted us to search for SIBO.

Outcome and follow-up

Repeated courses of antimicrobial agents (tetracycline, metronidazole, ciprofloxacin) were tried with prompt although unsustained INR shortenings, so that the patient required vitamin K supplementation in several occasions to maintain PT within the normal range. At the end of 18 months, in an attempt to reduce the bowel stagnation and its consequences, a side-to-side duodenal–jejunal anastomosis was performed. The patient’s recovery was uneventful, and 3 months later, her BMI was 19.2 kg/m2, and the INR was normal with no vitamin K supplementation. Since then, PT has been consistently normal and serum albumin, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, vitamin A and vitamin E were found normal time and again, but slight elevation of aminotransferases has persisted. Thirty-six months after the operation, small bowel dilation was still conspicuous (figure 2C) and the glucose breath test was close to the normal range (figure 2D).

Discussion

Dilated, stagnant small bowel and SIBO have previously been described as associated to several conditions, including intestinal malabsorption, liver disease and major gut surgery. This is the first description of SIBO associated to vitamin K deficiency. Visuthranukul et al reported a patient who, similar to ours, had long-lasting duodenal obstruction associated to a range of nutritional disorders, including vitamin K-responsive coagulopathy.5 In the reported case, SIBO was presumed but not demonstrated. In our patient, vitamin K levels were not measured, but the consistent therapeutic response to intravenous vitamin K administration indicates that the coagulopathy was caused by vitamin K deficiency. The diagnosis of SIBO was based on an abnormal glucose breath test, according to the criteria from the North American Breath Testing Consensus.6 Although the patient breath test was still positive after surgery, the H2 breath excretion profile was only slightly abnormal (Figure 2D), indicating a profound modification of the bacterial population. Nevertheless, persistence of abnormal H2 excretion may suggest that courses of antibiotic therapy may still be required in the future. The surgical procedure, facilitating the outflow of contents from the dilated bowel, succeeded in inducing complete and sustained correction of the coagulopathy, which was associated to marked improvement of nutritional indicators. Lack of previous sustained effect of antibiotics in our patient does not rule out SIBO, as this is a common occurrence, according to a meta-analysis on antibiotic therapy for SIBO.7

A remarkable finding in our case of SIBO secondary to bowel stagnation was the severe vitamin K deficiency resulting in coagulopathy, which contrasts with ordinary cases of SIBO whose vitamin K level is usually preserved, even when vitamin A, D and E deficiencies are demonstrated. Vitamin K deficiency in the reported case could result from reduced menaquinone-producing bacterial population, expansion of vitamin K-consuming microbial population or marked malabsorption. Our patient presented clinical evidence of long-lasting malabsorption, although this was not confirmed by a small bowel biopsy. Malabsorption in SIBO can be ascribed to different mechanisms, such as mucosal atrophy, mucosal inflammation and bile acid dysmetabolism.8 9 It is also possible that dysbiosis, besides bacterial overgrowth, may have caused imbalance in the gut microbiota composition, as has been reported in many human disorders.10 Finally, the persistence of hypertransaminasaemia in our patient may indicate some degree of liver injury that is likely to be due to hepatic exposure to noxious bacterial products caused by increased gut permeability determined by dysbiosis.8 11 12

Learning points.

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) may be associated to a vitamin K-responsible coagulopathy.

SIBO treatment with antimicrobials may fail.

When bowel disorder has an obstructive component, an operation may improve SIBO.

A plausible hypothesis to explain vitamin K deficiency in SIBO could involve qualitative alterations of bowel microbiota.

Footnotes

Contributors: All the authors have actively participated in the study and all have seen and approved the submitted manuscript. ALCM participated in the concept of the study and in the analysis and interpretation of data; RBO participated in the study concept, in the drafting and in the critical revision of the manuscript; LEAT participated in the execution and interpretation of glucose breath test and in the final revision of the manuscript; JEJ participated in the revision of the manuscript and in the selection and analysis of the images.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Quigley EM, Quera R. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: roles of antibiotics, prebiotics, and probiotics. Gastroenterology 2006;130(2 Suppl 1):S78–90. 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Grace E, Shaw C, Whelan K, et al. Review article: small intestinal bacterial overgrowth--prevalence, clinical features, current and developing diagnostic tests, and treatment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013;38:674–88. 10.1111/apt.12456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Giuliano V, Bassotti G, Mourvaki E, et al. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and warfarin treatment. Thrombosis Research 2010;126:12–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ford SJ, Webb A, Payne R, et al. Iatrogenic vitamin K deficiency and life threatening coagulopathy. BMJ Case Rep 2008;2008:bcr0620080008 10.1136/bcr.06.2008.0008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Visuthranukul C, Chongsrisawat V, Vejehapipat P, et al. Bleeding tendency in an adolescent with chronical small bowel obstruction. Asia Pac J ClinNutr 2012;21:642–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rezaie A, Buresi M, Lembo A, et al. Hydrogen and methane-based breath testing in gastrointestinal disorders: the North American Consensus. Am J Gastroenterol 2017;112:775–84. 10.1038/ajg.2017.46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shah SC, Day LW, Somsouk M, et al. Meta-analysis: antibiotic therapy for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013;38:925–34. 10.1111/apt.12479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Quigley EMM, Stanton C, Murphy EF. The gut microbiota and the iver. Pathophysiological and clinical implications. J Hepatol 2013;258:1020–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. King CE, Toskes PP. Small intestine bacterial overgrowth. Gastroenterology 1979;76:1035–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sekirov I, Russell SL, Antunes LC, et al. Gut microbiota in health and disease. Physiol Rev 2010;90:859–904. 10.1152/physrev.00045.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Leung C, Rivera L, Furness JB, et al. The role of the gut microbiota in NAFLD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;13:412–25. 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schnabl B, Brenner DA. Interactions between the intestinal microbiome and liver diseases. Gastroenterology 2014;146:1513–24. 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.01.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]