Abstract

Reactivation of chronic hepatitis B (CHB) can be associated with significant morbidity and mortality. There are many different causes of hepatitis B reactivation. This case describes an Asian woman with stable CHB presenting with significant hepatitis flare with markedly elevated serum aminotransferases and hepatitis B virus DNA level. The clinical symptoms were subtle with fatigue and vague right upper quadrant tenderness. We ruled out drug-associated hepatotoxicity and screened for common causes of acute hepatitis. Interestingly, she was noted to have reactive anti-hepatitis E virus (HEV) IgM at initial presentation followed by anti-HEV IgG positivity a month later. The serological pattern confirmed the diagnosis of acute hepatitis E. The combination of antiviral therapy for hepatitis B and resolution of acute hepatitis E resulted in normalisation of serum aminotransferases. This case illustrates the importance of taking a careful history and having a high index of suspicion for various aetiologies when evaluating patients with reactivation of CHB.

Keywords: hepatitis B, foodborne infections, hepatitis other

Background

Chronic hepatitis B (CHB) virus (HBV) infection affects approximately 360 million people worldwide.1 The prevalence of CHB in North America is about 1.4 million. CHB can result in progressive liver disease that leads to cirrhosis, liver failure and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).2 The treatment strategies of hepatitis B are based on early recognition of active disease and providing antiviral therapy to prevent disease progression and complications.1–4 Periodic reactivation of hepatitis B with fluctuations of serum aminotransferases and viral load is common especially among patients with Hepatitis B e Antigen (HBeAg)-negative CHB.5 Other recognised causes of hepatitis B reactivation include withdrawal of antiviral therapy after prolonged HBV suppression, pregnancy, chemotherapy for haemato-oncological malignancies, biological response modifiers for autoimmune conditions or profound immune-deficient states as in the organ transplant setting or development of HCC.1 4 6 Significant hepatitis flare has also been well documented with HIV and hepatitis D virus (HDV) superinfection. We encountered an interesting case of acute hepatitis E virus (HEV) superinfection leading to HBV reactivation.

Case presentation

The patient was a 39-year-old Vietnamese woman with history of HBeAg-negative CHB. She was documented to have HBV genotype B and presence of precore mutation. She was routinely monitored every 3–6 months in the outpatient liver clinic. She had relatively high level of viraemia with HBV DNA levels ranging from 5 log10 to 6 log10 (or 100 000–1 000 000) IU/mL. Her alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels had been persistently lower than 2× upper limit normal (ULN) (19 IU/mL in women).6 Liver biopsy from 1 year ago reported grade 1 inflammation, no steatosis and minimal stage 0–1 fibrosis. The patient was offered antiviral therapy for her high viral load in the past but she had declined. During a routine visit, she reported some fatigue without other associated symptoms such as fever, nausea, reduced appetite, abdominal pain or change in bowel habits. Her vital signs were normal. The only physical finding was mild right upper quadrant tenderness. There was no hepatomegaly, splenomegaly or stigmata of chronic liver disease.

Besides hepatitis B, the patient did not have other significant medical conditions. She did not consume alcohol and had not been taking any herbal or over-the-counter medications. On further inquiry, she reported regular pork consumption at home including a recent barbecue meal with pork meat at a restaurant. She had not had any recent travel, close contacts with sick persons and was not pregnant.

Investigations

Initial bloodwork from her visit was notable for elevated liver chemistry tests: ALT 1113 IU/L, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 742 IU/L, alkaline phosphatase 95 IU/L and total bilirubin 1.5 mg/dL. HBV viral load was greater than 8.5 log10 (or 170 million) IU/mL. Her white cell count was 2.7 K/µL, Hgb/haematocrit (HCT) 13.3/43, platelets 81 K/µL and iternational normalised ratio (INR) 1.2. Her previous platelet count was 197 K/µL with normal hepatic synthetic function. Abdominal ultrasound revealed no lesions or biliary dilatation, and patent portal vasculature.

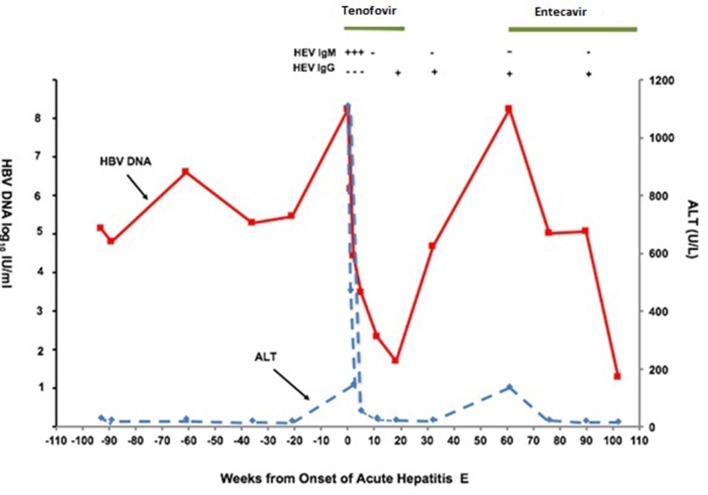

Due to her history of regular pork consumption, hepatitis E serology was obtained. Anti-HEV IgM was reactive with non-reactive anti-HEV IgG initially (see figure for serological and clinical course). She was tested negative for both anti-HEV IgM and IgG in a previous visit approximately 9 months ago. That further supported the diagnosis of acute hepatitis E.

Additional diagnostic studies included negative serological tests for cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and HIV. She had immunity to hepatitis A with total anti-hepatitis A virus positive. Hepatitis C antibody and hepatitis C virus RNA were negative. Anti-HDV was non-reactive. Her autoimmune markers including antinuclear antibody (ANA), antimitochondrial antibody (AMA) and smooth muscle antibody were negative previously.

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis of HBV reactivation include: spontaneous reactivation of hepatitis B, superinfection of other viral hepatitis such as hepatitis A, hepatitis C, hepatitis D, CMV infection, EBV and HIV infection, drug-induced HBV reactivation, autoimmune hepatitis and HCC. Pregnancy is also within the differential diagnosis for women in reproductive age.

Treatment

In the setting of hepatitis B flare, she was started on tenofovir 300 mg PO daily. Because she had minimal symptoms except for fatigue, treatment for hepatitis E was supportive.

Outcome and follow-up

On a follow-up visit 4 weeks after initiation of tenofovir, her symptoms of fatigue had resolved. Serial monitoring of liver chemistry tests showed normalisation of her serum aminotransferases with a reduction of HBV DNA to less than 2 log10 (less than 100) IU/mL after 8 weeks. Hepatitis E IgM became negative and IgG became reactive within 1 month (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

Time course of ALT and hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA level before, during and after acute hepatitis E virus (HEV) superinfection.

Four months later, the patient decided to discontinue treatment with tenofovir on her own as she was feeling well and did not want to take medication. She subsequently developed a second flare due to medication withdrawal with viral load greater than 8 log10 IU/mL (greater 170 million) and ALT increased to 140. After repeated counselling, she agreed to start on entecavir. She currently remains compliant with antiviral therapy with optimal viral suppression and normalisation of liver tests.

Discussion

Spontaneous fluctuating HBV DNA levels and serum aminotransferases are common during the natural history of HBV infection. There are well documented reports that the reactivation of hepatitis B can lead to hepatic decompensation among the immunocompromised patients. Significant hepatitis B flare as a result of superinfection with other viruses can also present among immunocompetent patients with stable liver condition. Our case of acute hepatitis E infection causing reactivation of hepatitis B underscores the importance of taking clues from the patient’s history to arrive at the correct diagnosis. Since the symptoms of acute hepatitis E can be subtle and non-specific as in our patient’s presentation, the aetiology leading to HBV reactivation can be overlooked or attributed to spontaneous disease fluctuations especially among patients with HBeAg-negative CHB.

There is paucity of reports on the effects of acute hepatitis E on the clinical course of CHB. In a retrospective cohort study of 228 cases, Chen et al evaluated the risk factors for adverse outcomes of CHB superimposed with acute HEV infection. They observed that most patients with cirrhosis with superimposed HEV infections developed hepatic decompensation compared with those without cirrhosis. Mortality rate was also significantly higher in patients with cirrhosis as compared with patients without cirrhosis (21.3% vs 7.5%, p=0.002). The majority (90.4%) of the patients did not have prior hepatic decompensation. Among the patients without cirrhosis, 38% were in an immune-tolerant phase of CHB prior to reactivation. The risk factors for poor outcomes among the patients without cirrhosis were intermediate (500≤HBV DNA<5 × 105 IU/mL) HBV DNA levels (OR 5.1, p=0.012), alcohol consumption (OR 6.4, p=0.020), underlying diabetes (OR 7.5, p=0.003) and kidney diseases (OR 12.7, p=0.005).7

Acute hepatitis E can be diagnosed by the detection of anti-HEV IgM. HEV antibodies may be negative in immunocompromised individuals. Thus, direct testing for HEV RNA in blood or stool is recommended.4 8 Based on the literature, acute HEV infection is generally self-limiting among the immunocompetent persons, and severe cases can be observed in patients with a pre-existing liver disease, pregnant women, and immunosuppressed individuals including those with organ transplantation, HBV and HIV infection.1 2 9 10

HEV is a positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus, and the sole member of the genus Herpesvirus in the Hepeviridae family.1 It has one serotype and four genotypes, and all of them are pathogenic to humans (see table 1).3

Table 1.

Characteristics of hepatitis E virus genotypes

| Characteristics | Genotype 1 | Genotype 2 | Genotype 3 | Genotype 4 |

| Geographic location | Africa and Asia | Mexico, West Africa | Industrialised Countries | China, Taiwan, Japan |

| Mode of transmission | Poor sanitation faecal–oral person to person |

Poor sanitation faecal–oral |

Food borne especially undercooked pork, game meat | Food borne |

| Groups at high risk for infection | Young adults | Young adults | Adults (>40 years), immunocompromised persons |

Young adults |

| Zoonotic transmission | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Chronic infection | No | No | Yes (immunocompromised) | No |

| Risk of outbreak | Common | Smaller scale outbreak | Uncommon | Uncommon |

Hepatitis E is estimated to have an incidence of 20 million infections worldwide leading to 3.3 million symptomatic cases of hepatitis E, and 56 600 hepatitis E-related deaths.9 The prevalence of HEV antibodies in USA is around 6% in general population.8 This recent data illustrated that the prevalence of hepatitis E in developed countries is not uncommon as it was considered before.2

HEV can also lead to chronic hepatitis E infection and cirrhosis in immunosuppressed individuals in the settings of solid organ transplant, haematological diseases and in AIDS.11 Chronic hepatitis E infection has only been reported in patients infected with HEV genotype 3 in developed countries.12

There could be incomplete reporting with other genotypes in the developing regions. Extra hepatic manifestations of chronic hepatitis E infection such as kidney injuries, haematological disorders and neurological symptoms have also been reported.12

There are two different patterns of HEV distribution. One is in resource-poor areas with frequent water contamination. Here, the disease can occur as massive outbreaks or sporadic cases. In industrialised countries, sporadic cases of hepatitis E have been reported with genotype 3 mostly from the ingestion of undercooked animal meat and are not related to food/water contamination.13

HEV has an animal reservoir, which makes it unique among other viruses. Meng et al documented that pigs act as natural reservoir for HEV and play an important role in its transmission to humans.8 14 Consuming contaminated meat products and direct contact with animals are the most important causes of HEV human infection in the industrialised countries.1 12 In one study, serum samples and survey questionnaires were collected from 2002 to 2009 in 335 undergraduate and veterinary students. They were inquired about consumption of meat and whether the meat consumed was undercooked to rare, medium rare or medium cooking conditions. The seroprevalence of anti-HEV antibodies in the study population was 6.27%. The rate of anti-HEV positivity among subjects who occasionally or always consumed meat products was 12.9 times of that among subjects who never consumed meat. This study showed the relationship of undercooked meat consumption and increased prevalence of HEV in undercooked meat in developed countries.1 15 Meng et al and Cossabom et al also tested the presence of HEV RNA in pork chitterlings and found HEV RNA in 3 of 12 samples tested (25%). All the three HEV RNA belonged to genotype 3 of HEV. The presence of HEV RNA in the pork chitterlings including small intestine suggested that HEV can also replicate in extrahepatic tissue.8 Besides pork livers, HEV can also be transmitted via consumption of undercooked rabbit and pork meats including sausage, chitterlings, skeletal muscle and nervous tissue.

16 17 In our case, the patient might have acquired acute HEV infection from the frequent consumption of pork meat even though there was no direct evidence to confirm the source of her infection. HEV, for instance, could be transmitted also through contaminated water sources where pigs were housed. We did not have HEV RNA or genotype data to support that; however, the negative HEV serological tests 9 months previous to the acute presentation strongly supported the diagnosis of acute hepatitis E.

Key prevention strategies for reducing exposure to HEV include improving sanitation in low-income/middle-income countries. Ensuring that meat products are thoroughly cooked, and appropriate measures in handling uncooked meat are potential preventive approaches. Prevention of transmission is theoretically possible by screening donated blood, but its cost effectiveness has yet to be established. HEV vaccine against genotype 1 is currently available only in China. Vaccination might be useful in high-risk groups such as immunosuppressed patients, patients with chronic liver disease and individuals intending to travel to endemic areas. Since all the genotypes of HEV belong to the same serotype, the vaccine apparently will be efficacious against all genotypes.

In conclusion, our case demonstrated that acute HEV superinfection can lead to significant hepatitis B reactivation in an immunocompetent patient. This underscores the importance of careful history taking and to perform the relevant diagnostic test.

Learning points.

Concurrent infection with another viral hepatitis should be considered in both immunodeficient and immunocompetent patients with hepatitis B reactivation.

Hepatitis E superinfection on chronic hepatitis B can contribute to significant morbidity and mortality especially in patients with pre-existing cirrhosis.

Hepatitis E has global distribution in low-income/middle-income and industrialised countries.

Hepatitis E can be transmitted with waterborne contamination, as well as raw or undercooked meat products.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the planning and writing the case report. AA and SI helped in writing the initial draft. SSC helped in revising the clinical vignette. AS and AA reviewed and revised the draft. DL contributed in the final revision of the manuscript. All authors approve the current draft for submission and assume responsibility for the accuracy and integrity of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Hou J, Liu Z, Gu F. Epidemiology and Prevention of Hepatitis B Virus Infection. Int J Med Sci 2005;2:50–7. 10.7150/ijms.2.50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hann HW, Han SH, Block TM, et al. Symptomatology and health attitudes of chronic hepatitis B patients in the USA. J Viral Hepat 2008;15:42–51. 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2007.00895.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kamar N, Bendall R, Legrand-Abravanel F, et al. Hepatitis E. Lancet 2012;379:2477–88. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61849-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pischke S, Gisa A, Suneetha PV, et al. Increased HEV seroprevalence in patients with autoimmune hepatitis. PLoS One 2014;9:e85330 10.1371/journal.pone.0085330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Farzi H, Ebrahimi Daryani N, Mehrnoush L, et al. Prognostic values of fluctuations in serum levels of alanine transaminase in inactive carrier state of HBV infection. Hepat Mon 2014;14:e17537 10.5812/hepatmon.17537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Terrault NA, Bzowej NH, Chang KM, et al. AASLD guidelines for treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology 2016;63:261–83. 10.1002/hep.28156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen C, Zhang SY, Zhang DD, et al. Clinical features of acute hepatitis E super-infections on chronic hepatitis B. World J Gastroenterol 2016;22:10388–97. 10.3748/wjg.v22.i47.10388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Meng XJ. Hepatitis E virus: animal reservoirs and zoonotic risk. Vet Microbiol 2010;140:256–65. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.03.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kc S, Mishra AK, Shrestha R. Hepatitis E virus infection in chronic liver disease causes rapid decompensation. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc 2006;45:212–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wedemeyer H, Pischke S, Manns MP. Pathogenesis and treatment of hepatitis e virus infection. Gastroenterology 2012;142:1388–97. 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hoofnagle JH. Reactivation of hepatitis B Hepatology 2009;49(S5). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kamar N, Izopet J, Dalton HR. Chronic hepatitis e virus infection and treatment. J Clin Exp Hepatol 2013;3:134–40. 10.1016/j.jceh.2013.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Teo CG. Much meat, much malady: changing perceptions of the epidemiology of hepatitis E. Clin Microbiol Infect 2010;16:24–32. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03111.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Meng XJ, Purcell RH, Halbur PG, et al. A novel virus in swine is closely related to the human hepatitis E virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997;94:9860–5. 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cossaboom CM, Heffron CL, Cao D, et al. Risk factors and sources of foodborne hepatitis E virus infection in the United States. J Med Virol 2016;88:1641–5. 10.1002/jmv.24497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Izopet J, Dubois M, Bertagnoli S, et al. Hepatitis E virus strains in rabbits and evidence of a closely related strain in humans, France. Emerg Infect Dis 2012;18:1274–81. 10.3201/eid1808.120057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Purcell RH, Emerson SU. Hidden danger: the raw facts about hepatitis E virus. J Infect Dis 2010;202:819–21. 10.1086/655900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]